ABSTRACT

With a long history as a vehicle for preserving perishable fillings against spoilage, pie was imagined as both a lavish banqueting centerpiece and an edible symbol of globalization in the seventeenth and eighteenth century British and early American worlds. Filled with expensive and difficult-to-obtain ingredients, and frequently sent over long distances in a culture of performative gift-exchange, pies were complex and multivalent objects. By examining the pie’s reputation as a means of preserving food alongside its widespread – but now largely forgotten – cultural association with death and dying, we suggest that for elite consumers, these pastry “coffins” could fulfill a similar function to memento mori: a reminder of the impermanence of organic matter and the inevitability of death and decomposition. Taking pie, an edible and ephemeral food, as a subject of material-cultural analysis, we can open unexpected avenues for understanding some of the emotions evoked by global consumption.

No man can tell what is in a pye till the lid be taken up.

-John Ray, A collection of English proverbs (Cambridge, 1678).

Introduction

This article takes pie – a baked dish with pastry encasing either a sweet or savory filling – as a starting point for consideration of global commerce, food, and death in the seventeenth and eighteenth century British and early American worlds. In this period, pies were devices in many senses of the word. They were used to preserve food, to make food last longer, and to prevent rot. Perhaps in part because of their preservative functions, pies were well-traveled, sent to friends and family members across long distances. Pies were embedded within global foodways, filled with ingredients sourced from around the planet. Reading into accounts, descriptions and reactions to pies found in first-hand accounts, it is clear that pies also inspired a wide range of emotions in the people who consumed them. These emotions included curiosity and delight but also, sometimes, fear and disgust. In fact, pies had a lively imaginative life, as they were debated and discussed in art and literary forms of many kinds. Pies served as elaborate metaphors and also as central tropes in some of the most popular and beloved works of the age.

While most scholarship on material culture has focused on non-edible things – portraits and gravestones, furniture and jewelry – this article contends that study of the edible offers revealing insights into the material worlds of the past. By considering representations of pies, and simultaneously the actual, edible pies that inspired them, we are able to valuably connect several key historiographies in material culture studies, food studies, and the histories of emotions as well as science. In the field of material culture, food remains, to a certain extent, an underexplored topic; it is worth asking whether edible things, by their very nature ephemeral, common, and consumable, can act as relevant objects of material study.Footnote1 In her 2014 Reviews in American History piece on Michael LaCombe’s Political Gastronomy: Food and Authority in the English Atlantic World, Trudy Eden questioned the limits and scope of whether “food, as an aspect of material culture,” should be part of good scholarly histories. “Sometimes food is just food,” Eden wrote, “and its value is that it satisfies hunger – no more, no less.” Eden urged the scholarly community to think carefully about how or whether to use food within studies of material culture, arguing that “its value to historians varies with its value to the actors at the time.”Footnote2

With Eden’s provocation in mind, we will work to suggest that pies were of value, a value both physical and philosophical, in the early modern British and American world. This interpretation is grounded in theories and interpretive strategies employed by scholars of material culture, who have shown that when objects represent themselves as something mysterious, different, other, or extra from what they actually are, we gain unique insights into the concomitant emotional, political, and cultural quandaries faced by the people who made and used them. These scholars have argued that, in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, an object’s abilities to alternately conceal and reveal served several purposes: these things helped people make sense of the world around them, reconciling themselves to things like death, loss, disaster, and corruption. These things helped people to self-fashion, to construct and reconstruct their identities as women and men, as national subjects and citizens, as small people in a suddenly bigger, globalizing world. These things, which included everything from forgeries to prosthetic limbs, and falsified documents to miniature “baby houses,” helped early modern British and early American people to fashion sense from nonsense.Footnote3 And taken together, these impressive scholarly works have made intellectual space for us to imagine how pies – things, as we will learn, of mystery and intrigue – might have served as important, thought-provoking, and yet edible objects of material culture for early modern British and early American people.

Along the way we will incorporate related insights and approaches from the histories of emotions, science, and food. That objects, and, particularly, food objects associated with people and places outside of metropolitan Britain, could inspire feelings of both excitement and disgust has been a recent topic for scholars of British empire and colonization.Footnote4 These works have shown that close attention to the emotions, ideas, and imagination surrounding food and food-objects enables us to better understand how advocates of British empire justified, scoped, and rationalized acts of conquest and colonization. Often these foods were swept up in the “New Science” of the period, where knowledge about food preservation, re-use, and experimental techniques designed to delay food spoilage was of particular importance across the increasing distances of Britain’s early empire.Footnote5

Research on pie sits at the juncture of all of these fields of scholarship. Our aims are not to prove that pie caused or was responsible for empire. Rather we seek to show that studies of food items, rather than being ephemeral or incidental or dilettante, are exceptionally revealing of the complex, often contradictory thoughts and feelings held by women and men as they navigated, either intellectually or physically, the early modern British world. Pies made early modern women and men think about global luxury. They also made them think about mortality and death. In tracing the cultural and social dimensions of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century pie, and then by turning to the symbolic life of these dishes in the early modern British imagination, this article offers a suggestive model for thinking about the intersections between food, things, and feelings.

The Pie in Practice

It can be challenging to define any food precisely, but pies were shaped by their etymology, flavor profile, and form. The word “pie” is English in origin, with its first uses traced to Middle English in the fourteenth century, variously written as pie, pey, pi, pye, pay, poi, and poy, often according to orthographic regional variation. Some suspect that the composite nature of this dish referenced the bird known as magpie (Pica pica), often nicknamed “pie” in the period, perhaps due to the magpie’s predilection for collecting miscellaneous objects. Food pies, similarly, were filled with many different ingredients. In the recipe for “Egg Pye, or Mince-Pye of Eggs,” in Hannah Woolley’s 1684 The Accomplish’d Ladies Delight, the author called for two dozen egg yolks, beef suet, pippin apples, currants, sugar, spice, carraway seeds, candied orange peel, verjuice, and rose water.Footnote6 In his 1685 instructions “To bake two Neats-tongues in a Pie to eat hot,” Robert May described a pie filling made of beef tongue, lard, beef suet, meatballs (themselves made with bread crumbs, cream, egg yolk, “bits of artichocks,” nutmeg, salt, pepper, and herbs), and then additional artichokes, marrow, grapes, chestnuts, bacon, and butter.Footnote7 Sometimes pies were even stuffed with other pies. Amelia Simmons’s late eighteenth-century American Cookery contained a recipe for “A Sea Pie” – a pie with multiple layers, invoking multiple decks on a sea-going ship – which was to be filled with “split pigeons, turkey pies, veal, mutton or birds.”Footnote8 The Oxford English Dictionary notes that linguistic associations between mixed foodstuffs and the magpie extend beyond England and the English language; Scotland’s iconic haggis, a dish of mixed meat, spices, and starches, has a name that is very similar to the Scots word “haggess,” meaning magpie.Footnote9 The magpie (or the haggess) has long been associated with eclecticism and variety.

From the 1300s onwards, foods and objects called “pies” shared some common characteristics in terms of seasoning, shape, and composition. Perhaps most notably, they were piquant. While pie fillings were various, containing meat, fish, eggs, and shellfish as often as they did fruit, they all tended to be highly seasoned, filled with spices, dried fruits, sugar, and alcohol.Footnote10 These ingredients served as indicators of wealth and purchasing power, but they also offered evidence of access to global markets. In 1674, Susanna Packe included a recipe for chicken pie in her British manuscript recipe book; this pie, filled with domesticated British farm birds, was made sumptuous by the addition of imported spices. Packe instructed her readers to season the chickens “with cloves & mace,” and then to lay “blad[e]s of large mace” on top of the meat.Footnote11 In early modern Britain, cloves and mace would have been sourced from Southeast Asia. The rest of the ingredients in Packe’s chicken pie were equally expensive; the chicken and spices were topped with preserved fruits, including dates, cherries, grapes, and gooseberries, and the pie was finished with white wine and sugar. Fruits such as cherries, grapes, and gooseberries were cultivated in early modern Britain, but eaten mainly by elite people; dates were imported from the Eastern Mediterranean. Most wines were brought from France, Spain, and Portugal. And sugar, a preservative in its own right, was harvested and made by enslaved Black women and men in Caribbean colonies and was another – albeit much more deeply troubling – global luxury good.Footnote12 If made according to the directions, Susanna Packe’s pie would have contained a host of global ingredients, and successful creation of this dish would have been predicated upon established systems of colonization, commerce, and enslavement.

Nor was Packe’s the only pie recipe with this kind of costly global signature. An anonymous seventeenth-century British recipe for “Artichoke pye” called for pepper (from the Malabar Coast), nutmeg (from the Molucca Islands), sugar (from the Caribbean), and candied orange and citron (from the Caribbean and the Western Mediterranean).Footnote13 Another anonymous manuscript British recipe book c. 1720 stated that “Minced Pies,” should include currants (the Eastern Mediterranean), brown sugar (the Caribbean), cinnamon (Sri Lanka), and cloves and nutmeg (the Molucca Islands) alongside metropolitan ingredients such as beef tongue, raisins, brandy, birch wine, and apples.Footnote14 Written in the same place and period, Lettis Vesey’s “Carpe Pye” recipe instructed users to “Season it Pretty high” with nutmeg and mace (also from the Molucca Islands) as well as pepper and “a little Ginger” (the Malabar Coast), all of which, the author-compiler believed, would complement the mix of seafood inside the crust: anchovies, carp, eels, and oysters.Footnote15 Eliza Pinckney’s 1756 South Carolina recipe book included instructions for “Mince pyes,” which contained cloves and mace, cinnamon, sugar, “candied orange and Cytron,” and dates, lemons, currants, and raisins.Footnote16 Another South Carolina Book, kept by Mrs. William Timmons, likely Isabella Darrell Timmons (1771–1843), also held a recipe “To Make Minced Pyes,” calling for cloves, nutmeg, sugar, and brandy (which was probably sourced from France).Footnote17 And Pinckney and Timmons’ mince pies, if or as they were made in South Carolina, would almost certainly have been prepared by enslaved women and men.

In Penelope Jephson’s British recipe book, global trade routes and elite practices of consumption were tied together through instructions on how a pie was supposed to be eaten in addition to how it was supposed to be made. Jephson explained that her “Hare pye” was to be seasoned with “pepper & salt & little nut meg,” which, as we have seen, were ingredients sourced from South and Southeast Asia. But Jephson also insisted that, when the pie was consumed, one should “serve it hot with a glass of French wine,” a further indication of status, purchasing power, and the elite culinary imagination.Footnote18 Spices were so closely associated with pies that, when the infamous Captain James Cook received a fish encased in bread from an Unangax or Alutiiq man in 1778, the strong seasoning in the food helped him to imagine it as a pie: “I received by the hands of an Oonalashka man, named Derramoushk, a very singular present, considering the place. It was a rye loaf, or rather a pye made in the form of a loaf, for it inclosed some salmon, highly seasoned with pepper.”Footnote19

In addition to their eclectic composition and strong flavor profile, pies shared elements of construction. That pies were similar to one another, or that they were made in similar fashions, was recognized within the period; in Elizabeth Coultas’s mid-eighteenth-century Pennsylvania manuscript recipe book, the author-compiler noted in the recipe “To make a Pigeon Pye” that “a Chicken or capon pye is made the same way.”Footnote20 What constituted a seventeenth and eighteenth-century pie? They had pastry: made with flour, water, and fat, this pastry was rolled smooth and shaped to the tops, bottoms, and/or sides of the pie, which secured the filling in the middle.Footnote21 They were baked: in the Canterbury Tales, Chaucer’s Cook could “wel bake a pye.”Footnote22 This baking was either done over an open fire or in an oven, with temperatures varying according to the type of pie being cooked; in Amelia Simmons’ American Cookery the author noted that “all meat pies require a hotter and brisker oven than fruit pies.”Footnote23 They could be large: the seventeenth-century diarist Celia Fiennes compared a man’s enormous velvet cap to a “great bowle in the forme of a great open pie,” and some of the pies that were used as banqueting centerpieces were even large enough to house a small, living human.Footnote24 Finally, unlike most other foodstuffs, pies were imagined as whole, intact, unbreachable structures, at least until the moment when they were ready to be consumed. This mind-set is perhaps most neatly encapsulated in Charles Dickens’s Nicholas Nickelby of 1839, when the character Mrs. Squeers scolds a young Nickelby for asking for pie when he has no appetite: “it’s a pity to cut the pie if you’re not hungry.”Footnote25

Squeers’s reluctance to cut into Nickelby’s pie may have been a reflection of the crust’s important preservative function. Since its inception in Britain around 1300, pie crust had functioned as a sort of ongoing culinary experiment; a tool used by bakers and household cooks to make perishable sources of protein last longer. Premodern pies, baked with thick crusts and firm crimping, created hot, air-tight environments which helped to ensure that their contents would not be exposed to bacteria and therefore would not rot or become inedible. Gelatin and fat were also used to preserve fillings, because adding thick layers of airtight jellies, fats, and oils around perishable fillings kept the interior of the pie from exposure to the air and thus bacterial spoilage. In English gastronomy this use of fat has often been called “potting” although in French gastronomic traditions a similar, although not identical, process is called “confit.”Footnote26 Constance Hall’s 1672 recipe for turkey pie offers evidence of the ways that early modern people approached these preservation methods. Hall instructed her readers to “Bone the Turkey and Larde it with fatt Bacon and season it with peper and Salt and Cloves and mace and nutmeg.” They were then to “put butter in the Pye and Bake it 4 howers.” Larding the turkey and putting butter in the pie would certainly have helped to create layers of fat in and around the meat, but even this wasn’t quite enough; Hall then explained that “when it [is] Bakt fill it with Clarrifi’d Butter.”Footnote27 This final pour of melted, clarified butter – which, with its milk solids and water removed, was itself more resistant to spoilage than fresh butter – would have sealed the filling inside of the crust with the intention of keeping it solid, firm, and nonperishable.

The potting method appears in recipe after recipe in early modern cookery books, both manuscript and print, with authors describing in detail not only how to preserve the fillings of pies with fat, but also why this method was important. In Elizabeth Raffald’s The Experienced English Housekeeper, the author explained that “the hole in the middle with cold butter” would keep the pie from spoilage, for it would “prevent the air from getting in.”Footnote28 The type of meat used in the pie also mattered; cooks needed to compensate for leaner cuts. A 1658 printed cookbook attributed to Théodore Turquet de Mayerne told readers that “in case your pasty be of Venison, or of any other viand that is not fat … you must needs have one half pound or three quarters of a pound of fresh butter to wrap the [meat] in, and at least one pound and a half or two pounds of fat Bacon, as well to lard your Viand, as to cover it after it is empasted.”Footnote29

If made correctly, this fat-sealing method could, potentially, produce a pie with a filling that would remain edible for substantially longer than it might have otherwise. Hannah Bisaker, author of a 1691 manuscript recipe book, suggested that a turkey pie prepared in this fashion “will keepe for a quarter of a yeare without Moulding.”Footnote30 The writer of “Macies Booke,” another manuscript recipe book produced at around the same time as Bisaker’s, agreed: “keep it in a Dry place,” she wrote in her recipe for swan pie, and “it will keep good a Quarter of a year.”Footnote31 The “Dry place” mentioned here, which could have included shelving, closets, boxes, or cupboards, either inside of the kitchen or outside of it, would also have helped to prevent mold and preserve food.Footnote32 Other writers offered still more ambitious and probably unrealistic estimates: the culinary author William Rabisha, for instance, claimed that his venison pie would stay good for a full year, provided that the cook made their crust from coarse rye flour and kept their “funnel stopped with a piece of butter.”Footnote33

Culinary authors thus paid close attention to fat and sealing, but they also shaped their pie crusts with care, making sure that the pastry was made in ways that would prevent bursting and leakage. Mayerne explained that creating a very “short” crust, or one with a lot of butter or fat added to it, could compromise the pastry: “note this also that the crust being so fat, may be subject to burst in the Oven.”Footnote34 Strong, thick pie crusts were typically praised as admirable and desirable, but sometimes the rigidity of a pie could stray into the absurd. Writing of white colonizers living on the Delaware River in the mid-eighteenth century, the Swedish Lutheran missionary Israel Acrelius noted that the pies they created were called “House-pie[s],” and that these foods, eaten “in country places,” contained crude fillings including “apples neither peeled nor freed from their cores.” These Mid-Atlantic pies may not have been perceived as elegant or even edible, but they could take a beating; according to Acrelius, their “crust is not broken if a wagon-wheel goes over it.”Footnote35 Although the people who made and ate Delaware River house-pies were, at least in theory, Acrelius’s own constituents, and although Acrelius was on the whole full of praise for the bounty and variety of food in the Americas, the anecdote was nonetheless probably intended to poke fun at some of the Delaware River Valley’s British and Scots-Irish colonizers. Acrelius described them as rustic and unsophisticated both in terms of their palates and in terms of their pie-making techniques.Footnote36

Israel Acrelius’s anecdote highlighted stereotypes about the supposed rusticity of some regions of the Americas. It also suggests that, despite its global profile, pie could be influenced or shaped significantly by local foodways. Moving forward into the Early Republic, Amelia Simmons’s American Cookery included instructions on how to make an older, perhaps well-traveled, pie seem more appealing and edible. The recipe for “Minced Pies, a Foot Pie,” explained that the pie could be constructed and baked far ahead of time and then warmed up using a specialized technique:

Weeks after, when you have occasion to use them, carefully raise the top crust, and with a round edg’d spoon, collect the meat into a bason, which warm with additional wine and spices to the taste of your circle, while the crust is also warm’d like a hoe cake, put carefully together and serve up, by this means you can have hot pies through the winter, and enrich’d singly to your company.Footnote37

Simmons’s recipe is notable for several reasons. She portrayed as a benefit her assurance that the pies would keep for “weeks after” and could be put on the table “when you have occasion to use them.” Lifting the lid, scooping out the contents for reheating, slipping the filling back into the crust, and then heating the lid would allow “your company” or “your circle” – the other white, free people with whom Simmons imagined her reader dining – to maintain the illusion of eating a fresh pie. Simmons’s pie promised a kind of thrift, even as it allowed her early American readers to imagine and enact luxury.

Even more revealing is Simmons’s deliberate use of “a hoe cake.” This reference point located Simmons’s minced pie firmly within the foodways of the early Americas. Hoecakes, a variant of the pancake, were made from cornmeal.Footnote38 Products made of maize, including those made with maize flour, were imagined by Europeans and their descendants as originating with and centrally consumed by Indigenous women and men. As Rebecca Earle has argued, this link emerged as early as the fifteenth century, when invading Spaniards racialized and denigrated maize as food by and for Indigenous Mesoamericans, worrying that too much consumption of foods like corn by white women and men would cause illness or racial “degeneration.”Footnote39 These associations continued for hundreds of years. Corn was tied so tightly to Native foodways, both real and imagined, that in the infamous 1779 Sullivan-Clinton Campaign, which saw the US Army’s purposeful destruction of hundreds of acres of Haudenosaunee corn, maize was burned to prevent Native people from thriving, a deliberate application of what Rhiannon Koehler has called “scorched-earth tactics with the intention of entirely destroying the population of Iroquoia.”Footnote40 Colonizers consistently imagined corn as Native, even as they attempted to obliterate Native cornfields and simultaneously grew and ate corn themselves.

Simmons’s reference to hoecakes also associated her recipe with the foodways of Black women and men. Hoecakes were said to be made not on a standard pancake griddle, but on the heated, flattened side of a field hoe. They were imagined as a food of and for field laborers, and specifically enslaved Black laborers. Historian Michael Twitty has called the hoecake “the hardtack of slavery,” a food which was central to the diets of Black women, men, and children in the Americas, and was “nearly universal.”Footnote41 In invoking hardtack, Twitty gestures here to the meager provisioning of enslaved people by white enslavers, but also to the hoecake’s durability and relative imperishability. By instructing readers that they should reheat the pie lid so that it was “warm’d like a hoe cake,” Simmons conveyed her implicit assumption that her imagined readers, most of whom were white New Englanders, would understand how a hoecake looked, tasted, and was made.Footnote42 She simultaneously connected her recipe to extant early American Black and Indigenous foodways, even if she did so inadvertently.

While it is impossible to know with certainty how long any given pie-filling would have stayed fresh, these techniques – potting, spicing, and crimping – encouraged a surprisingly long-distance trade in pie gifts. On March 16, 1663, for instance, the politician Sir Daniel Fleming paid £1 to a courier for “Ye carryage of 2 Pies” weighing over one hundred pounds from Westmorland to London, a distance of almost three hundred miles; this journey would have taken well over a week.Footnote43 Fleming apparently intended these as gifts for two of his professional acquaintances; he also recorded similar payments for gifts of “charr-pies” (filled with a type of freshwater fish), two of which were sent to the Earl of Carlisle, and one to an aunt in London.Footnote44 Such generosity was not cheap; based on Fleming’s accounts, Mary Wondrausch has estimated that the cost of sending a pie by courier in seventeenth-century England was approximately twopence per pound of pie.Footnote45 Some author-chefs had even greater ambitions. An anonymous 1737 work titled The Whole Duty of a Woman explained that a recipe quite similar to, although not quite the same as, a pie – collared beef, with flank steak potted in beef suet, and served in a clay pot with a pastry lid – would “keep good to the Indies,” signaling that elite Britons might aspire to send perishable foods that closely resembled pies across an ocean as well as between country and city.Footnote46 The significant expense and general impracticality of such an undertaking meant that a present of pie could be a lavish gesture of friendship or fealty, part of a culture of performative gift-exchange that retained its importance for the upper crust of society.

While an early modern pie cook or pie consumer could be reasonably confident that these preservation techniques would ensure that their foods would arrive in good condition, it was never a sure thing. This uncertainty made itself known in interesting ways; when pies were given as gifts, donors and recipients expressed their anxieties (or sent their reassurances) about the wholesomeness of pies. Seventeenth-century correspondence from the Hastings family, the Earls and Countesses of Huntingdon, helps to illustrate this point; multiple generations of Hastings women and men wrote letters about pies. In 1650, Lucy Hastings told her husband Ferdinando that she would be “glad to know whether … [my mother-in-law] liked the pye I sent up about a month or 5 weeks agoe.”Footnote47 In 1661, Beatrix Clerke was sent into an agony of embarrassment when “upon Satterday … I had the honor to receave [Theophilus Hastings’s] … Noble present [of a pie],” but was “disabled by some distemper in my boddy” which kept her from sending her immediate thanks. Clerke worked very hard to reassure Hastings about the size, durability, and quality of this pie, “humbly beseeching your honor to accept of my pore heerte … to relat the excelency of the Pye: how many friends I had, persons of honor and others of good repute, at the eateing of it.”Footnote48 In 1673, Bridget Croft also wrote to Theophilus Hastings to thank him for “a basket with a noble [salmon] pye.” Despite her excitement, Croft refrained from eating the salmon pie, waiting until she had guests; she “did not cut it tell they came,” and when they did, “it was opened and eaten of and found most excellently good.”Footnote49 And finally, in 1682, Mary Leke wrote to her sister Elizabeth Hastings that she had sent a mutual friend “a wodcock pye,” and she urged her sister to sneak a “tast of [it] and teall me [if] it is good.”Footnote50 The Hastings family did clearly like their pies. Filled with proteins often reserved exclusively for the nobility, such as woodcocks, venison, salmon, and other wild-caught meat, these foods were expensive gifts. It’s no accident that two of the Hastings correspondents called the pies they had received “noble.” But the anxieties expressed in their letters may also offer evidence of the ranges of emotions evoked by pie, including self-doubt, obsequiousness, meekness, and insecurity.

For while opening a pie crust could be a happy surprise, it could also be a horrible one. The somewhat unreliable method of preservation based upon airtight crusts and fatty fillings meant that the contents of a pie could become treacherous. In August 1700, for instance, noted botanist Robert Uvedale wrote a letter to his friend Richard Richardson to thank him for a pie of heathcocks (black grouse) that he had received as a gift from Richardson earlier that year. The pie in question had traveled approximately two hundred miles from Bierley Hall in West Yorkshire to Uvedale’s estate in Middlesex.Footnote51 Although Uvedale was able to report that “The Pye came very well, undamaged in ye least,” he noted with regret that “the Fowle, by the length of ye journey, were injured.”Footnote52 Uvedale requested that Richardson send him another heathcock pie the following season, and proceeded to give detailed instructions for preparing the meat to ensure that Richardson, or more likely, Richardson’s cook, would not make the same mistake again:

…putt them into an earthen pott, & with a little butter and bake them; when bakd, take them out, & lett all ye liquor drain from them, when cold putt them into a pott again, melting some butter fine, scumming of ye top and leaving what is thick at bottome, with this pour’d over them that they may be coverd the thicknesse of a Crown peice or more, they will probably keep well, especially if a little higher seasond then these sent.Footnote53

It is worth noting that the technique Uvedale described, in which the pie filling was cooked, drained, and cooled before being returned to the crust, probably would have accelerated spoilage rather than preventing it. But this letter does offer an unusually detailed description of one pie-lover’s attempt to preserve meat from rotting. This account gestures toward the implicit knowledge that early modern recipe books often assumed on the part of the reader. Uvedale concluded his recipe with an anonymous attribution, claiming that “This I have from ye learned in Kitchin & the Pastery, and they tell me tis authenticall.” His language, with its emphasis upon empirical knowledge received from a “learned” and trusted authority, echoes that of the experimental natural philosophy to which he devoted much of his professional life. Here, too, the source of the privileged information being shared helps to disprove older scholarly assumptions that anything related to the “New Science” was socially rarefied and exclusively masculine. As Simon Werrett demonstrates in this special issue, and as other scholars have shown, these sorts of practical “food-hacks,” conceived in the heat and clamor of the early modern kitchen, were integral to the culture of experimentation that defined the natural philosophy of this period.Footnote54

The Imagined Pie

The early modern pie thus was shaped and marked by globalization, conspicuous consumption, and patronage. As we have seen, it was also shaped and marked by attendant emotions: worries about preservation and perishability; delight in the taste of luxury goods; fears about correctly adhering to the social expectations around patronage, family obligations, and friendship. The final part of this article therefore will turn more explicitly to this cultural-imaginative life of pie, showing how its preserved, concealed, and gradually decaying interior could become, for many Britons, a space for anxious reflection.

In the British and early American cultural imagination, pies could serve as symbols for mystery and intrigue. As Israel Acrelius’s account of the semi-indestructible Delaware River house-pie makes clear, early modern pie crusts had a reputation for endurance. Thick, tough, and sturdy, these crusts were not lauded for their flakiness or tenderness but rather for their ability to withstand long journeys and rough handling. Such was their imagined durability and longevity that they sometimes were used to store or conceal objects never intended to be eaten. The English lawyer William Noy, for instance, who served as Attorney General under Charles I from 1631 to his death in 1634, was reported to have used “a Pye, which had been sent him by his Mother” as a storage unit for his miscellaneous papers and legal documents. Even the best-made crust could only last so long, however; Noy allegedly kept using the pie as a makeshift container “till the moldiness and corruptibleness of it had perished many of his Papers.”Footnote55 Even though Noy’s pie eventually turned against him, the thick pastry lids of early modern pies suggested that their contents – whether edible or not – might remain hidden from prying eyes, and so potentially could be appropriated for clandestine purposes. The infamous seventeenth-century Polish military commander Stanisław Koniecpolski was alleged to have escaped imprisonment from the impregnable Fortress of the Seven Towers in Constantinople by means of “a Silken cord sent in a Pye, with Limes and Files to cut the Iron bars.”Footnote56

Such tall tales reflect the fact that early modern pie-crust lids, designed to contain and conceal, also were widely associated with spectacle, entertainment, and trickery. The dark, hidden interior of a pie could serve an equally performative function to its ornate exterior, providing a creative medium through which elite diners’ expectations of their food might be radically inverted. Robert May’s popular Restoration cookbook The Accomplisht Cook (1660), for instance, included instructions for preparing a brace of huge, thick-crusted pies built to temporarily hold live frogs and birds. May took relish in the chaos and confusion that would likely ensue: “lifting first the lid off one pie, out skips some Frogs, which makes the Ladies to skip and shreek; next after the other pie, whence comes out the Birds; who by a natural instinct flying at the light, will put out the candles; so that what with the flying Birds and skipping Frogs, the one above, the other beneath, will cause much delight and pleasure to the whole company.”Footnote57 May’s description suggests that pies were meant to evoke a range of emotions, encompassing fear, with diners made to “skip and shreek” in shock, but also senses of “delight and pleasure” in the spectacle of live animals rising from dishes that were ostensibly cooked.

This interplay between unease and pleasure, ignorance and knowledge, and luxury and the macabre was also referenced in contemporary proverbs and in nicknames for pie. A seventeenth-century English proverb held that “Pye-lid makes people wise,” because, as the naturalist John Ray explained, “no man can tell what is in a pye till the lid be taken up.”Footnote58 It is likely that the Jacobean playwright John Webster was drawing upon this trope when, in his 1612 play The White Devil, he has one of his characters say to another: “As if a man/Should know what foule is coffind in a bak’t meate/Afore you cut it up.”Footnote59 Webster’s use of “coffind” here, to describe a pie crust as akin to a receptacle for human remains, was not unusual. Early modern English pie crusts were known widely as “coffins,” a word originally referring to a container, but which, perhaps, could have served as an additional grim reminder of their ability to seal and preserve perishable flesh. The word “coffin” was used to describe pie crust as early as the fifteenth century, and this nomenclature continued to be used routinely, in both print and manuscript, through much of the eighteenth century.Footnote60 The cook-author William Rabisha, for example, included a recipe for turkey pie in his 1661 printed recipe book, where he told readers to make turkey pie by taking the prepared, seasoned bird and “put him into your Coffin prepared for it, lay on butter, and close it.”Footnote61 And in Ann Smith’s 1698 manuscript recipe collection, the author-compiler used both terms in instructions “To Make A Chicken Pye,” explaining that seasoned meat should be placed “in A round Dish Coffin,” with the word “Dish” crossed out in favor of the word “Coffin,” signaling that the food should be baked entirely in pastry, rather than just with a pastry top.Footnote62 Since the basic goal of such preservation was to extend the period between death and decomposition, the relationship between the early modern pastry coffin and its funerary counterpart may have been more than just etymological.

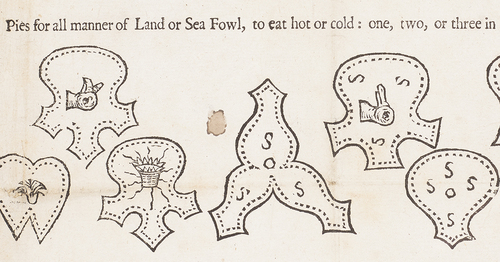

For although pies were imagined as symbols of mystery, shock, and entertainment, they were also closely associated with death. In print and in imagery, authors, artists, and food-workers played on the multiple meanings of “pie,” and “coffin,” drawing parallels between the way that dead human body parts rested in wooden or lead coffins, and dead animal body parts rested in pastry ones. Although not all pies were savory or meaty, it was common practice to decorate the lids of meat pies with severed animal heads, feet, and other body parts, ostensibly to signal to diners what sort of meat they could expect to find upon cutting into them. Rabisha’s (Citation1661) recipe for turkey pie called for readers to “put the head on the top with your garnish,” and his recipe for swan pie similarly instructed “put on the head and legs on the top.”Footnote63 This practice was continued by Rabisha’s fellow cook-author Robert May. There were many illustrations of designs for pies included in editions of May’s Accomplisht Cook, with frequent reference to either real or figurative animal remains. May’s instructions for fish pies typically included an image of the whole, dead fish, followed by an image of the model pastry crust which was designed to mimic its shape.Footnote64 And in the 1685 edition of his work, instructions for “Dishes of minced Pies for all manner of Flesh or Fowl,” were offered to readers, who were told to shape their pies “according to these Forms,” with decorative bird heads marking the tops ().Footnote65

Figure 1. Detail from Robert May, The accomplisht cook (London, 1685), the Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, Vet.A3 e.289, facing p. 241. Creative Commons license CC-BY-NC 4.0.

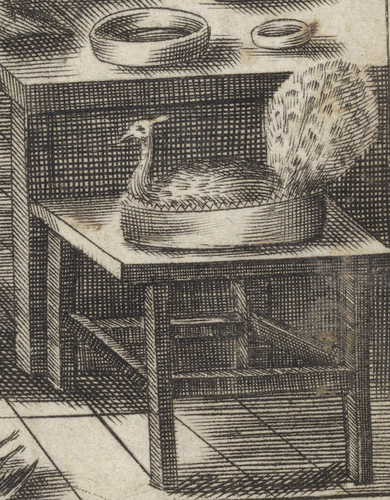

Contemporary works of art give us a sense of the scope and shape of early modern pies as well as the ways that animal heads and legs were used as a decorative motif. Joos Goeimare’s 1650–1687 View of the interior of a lavishly stocked kitchen includes the figure of an early modern cook carrying a meat pie; the dish has firm, high pastry sides and is decorated with a bird’s head sticking out of the top ().Footnote66

Figure 2. Joos Goeimare, View of the interior of a lavishly stocked kitchen (Venice, circa 1650–1687), ART 270,713 (size XXL), Folger Shakespeare Library. Image courtesy of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

Figure 3. Detail from Joos Goeimare, View of the interior of a lavishly stocked kitchen (Venice, circa 1650–1687), ART 270,713 (size XXL), Folger Shakespeare Library. Image courtesy of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

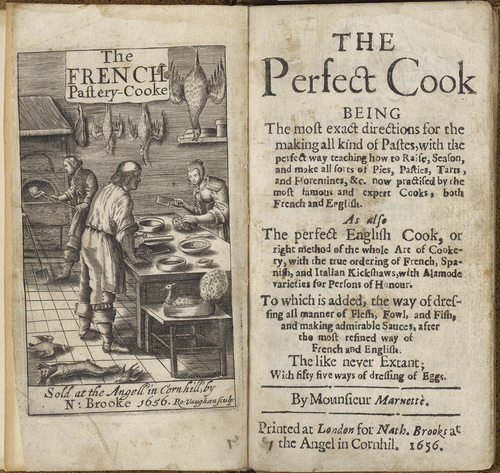

An engraved frontispiece to the 1656 The perfect cook, attributed to a “Monsieur Marnettè” includes an image of an even more ambitious animal pie. Shaped like a live peacock, the decoration for this pie included not only the head of the bird, but also its long tail feathers ().Footnote67

Figure 4. Monsieur Marnettè, The perfect cook… (London, 1656), M706, Folger Shakespeare Library. Image courtesy of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

Figure 5. Detail from Monsieur Marnettè, The perfect cook… (London, 1656), M706, Folger Shakespeare Library. Image courtesy of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

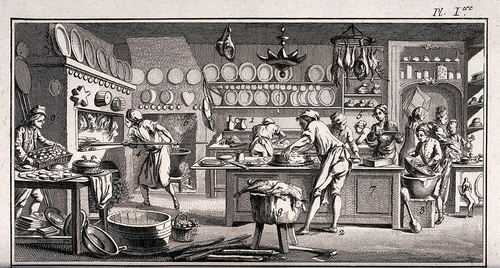

Like the image of the pie in Goeimare’s image, the peacock pie depicted in The perfect cook has fixed, high pastry walls. Themes of death and pie are further emphasized in the surrounding kitchen scene: the chef standing next to the peacock pie rolls and folds pastry at a table; on the floor of the kitchen, dead birds and a dead rabbit or hare lie scattered, waiting to be interred into their own pastry coffins. These decorative motifs apparently were so widely recognized that their use extended into the eighteenth century; when Diderot and d’Alembert included an image of a bakery in their iconic 1763 Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, par une Société de Gens de lettres the engraving featured a high-sided pie with two bird heads protruding from the pastry crust ().Footnote68

Figure 6. “Many people are busy in the baker’s kitchen preparing cakes, pastries, pies and bread,” N.D., Wellcome Collection 31301i. Engraving by Bernard. Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark. Plate from Denis Diderot, Jean-Baptiste le Rond d’Alembert (eds.): Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers (Paris 1763).

Figure 7. Detail from “Many people are busy in the baker’s kitchen preparing cakes, pastries, pies and bread,” n.D., Wellcome Collection 31301i. Engraving by Bernard. Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark. Plate from Denis Diderot, Jean-Baptiste le Rond d’Alembert (eds.): Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers (Paris 1763).

These descriptions and images from recipe books and works of art, in which pies were decorated with either real or fabricated dead animal parts, offer us a sense of the shape and structure of early modern pies. They also provide some suggestive complementary background for the numerous examples of early modern British authors who enjoyed playing with the relationship between pies and death. For many authors, it was the concealing pie crust which provoked both dread and amusement. In (Dekker’s Citation1603) The Pleasant comodie of patient Grisill, the character Farneze laments the empty dishes left at the end of a banquet, for “there standes the coffins of pyes, wherein the dead bodies of birdes should have been buried, but their ghostes have foresaken their graves and walkt abroad.”Footnote69 When the prose-poet Nicolas Breton wrote his 1626 book entitled Fantasticks, he drew upon the culinary motif of the pie-crust as coffin: “the Woodcocke and the Pheasant pay their lives for their feed, and the Hare after a course makes his hearse in a pye.”Footnote70 Ben Jonson’s early Caroline play The Staple of News has the aged Pennyboy Senior whine that his detractors claim he “preserves himselfe, Like an old hoary Rat, with moldy pye-crust.”Footnote71 Here Jonson is playing on the word “preserve,” implying that Pennyboy Senior is living off crusts, but also that, as a character mocked for his great age in the play, he himself is soon destined for a coffin.

For other authors, it was the pie’s filling – where many ingredients mixed together with pungent spices – which made it suspicious and provoked feelings of curiosity and fear. In literary works from the period, the fleshy fillings of pies were frequently imagined as mysterious, not easily identifiable, and even macabre: Shakespeare’s character Titus Andronicus famously bakes the characters Chiron and Demetrius into a pie, which he then serves to their mother Tamora.Footnote72 The 1607 stage comedy The Puritaine or the widow of Watling-streete, attributed to Thomas Middleton, includes a funeral scene in which a bereaved son states, “my fathers layde in dust his Coffin and he is like a whole-meate-pye, and the wormes will cut him up shortlie.”Footnote73 And in 1624, the playwright Thomas Heywood described the execution of a woman for the alleged crime of “killing young infants, and salting their flesh and putting them into Pyes, and baking them for publike sale.”Footnote74 Dekker, Breton, Jonson, Shakespeare, Middleton, and Heywood were some of the most well-known authors of their age; their frequent references to pies and coffins suggest that these were widely recognized tropes. And they were tropes which were designed to invoke wide ranges of emotion, from pleasure to horror.

That pies were linked to death in print and in manuscript, in literature and in art, and that these food objects were capable of triggering so many different emotions, suggests that these foods could function as a sort of edible memento mori, a playful but sobering reminder of the inevitability of death and the transience of material pleasure.Footnote75 Memento mori, a phrase signaling “remember that you [will] die,” was a widespread and widely-recognized early modern phrase, message, lesson, and trope.Footnote76 While it could take many forms – including, but not limited to, statuary, painting, literature, and acts of performance and drama – one of the most striking and widespread was the memento mori miniature: a personal, material object, designed to be worn or carried on the body. Often tiny, lidded coffins with skeletons inside of them, these wearable mementos were luxury objects designed to evoke a seemingly contradictory set of emotions, from fascinated pleasure to anxious self-reflection and even dread.

The two objects below, both from the Wellcome Collection in London, serve as representative examples of this kind of wearable death art (). From the outside, each of these objects could pass for a piece of luxury religious jewelry or a work of decorative art; but once the lid was prized open, revealing the wax, ivory, wooden, or metal skeleton reposing inside, the viewer would be confronted with a stark reminder of their own mortality. That memento mori objects like these coffins were sometimes brought in proximity to food is very suggestively, but also very interestingly, referenced by the London woodturner Nehemiah Wallington. In 1621 Wallington, a man of comparatively modest means, reported that he had put himself to “grate charge in buying Anotime [Anatomy] of Death and a little black coffin to put it in, and upon it written Meemento Mory.”Footnote77 According to Wallington’s scrupulous spiritual diaries, he was in the habit of placing this object “upon a ginstoul by my bedsid every night” along with “some meals to stand upon or by my Table. All this,” he explained, “was to put me in mind and feet me for death.”Footnote78 Wallington was not speaking of pie specifically in this entry. But the fact that Wallington placed his memento mori in close proximity to his late-night sustenance suggests that food could serve as a potent reminder of the instability of organic matter and its inevitable decay.

Figure 8. A gold memento mori pendant, used to remind the user of the transience of life and material luxury, containing a decaying corpse inside a coffin. (Open). Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC by 4.0).

Figure 9. A memento mori statue, used to remind the user of the transience of life and material luxury, containing a decaying corpse inside a coffin. Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC by 4.0). The corpse has worms coming out of its stomach, a reminder that human bodies are themselves destined to one day become food.

For British consumers, these memento mori coffins opened to reveal something surprising and, in some ways, shocking. That these emotions were contradictory did not make them any less evocative. If pies did function, at least to some extent, as a kind of memento mori, they offer one suggestive example of how an edible object might also serve as a piece of material culture. Pies were popular foods, but they were also popular think-pieces, appearing in literature and in art, offering evidence of some of the ways that food, materiality, and mortality became entangled in the early modern cultural imagination.

Conclusion

There was a lot going on beneath the lid of an early modern pie. This article has sought to demonstrate that, in addition to its origins as a means of preserving food from spoilage, the pie served as a symbol of luxury, grandeur, and excess, a reminder of both the pleasures and the horrors of material existence and the inevitable decay of organic matter. As we have seen, pies filled with preserved meat and encased in a thick pastry “coffin” could be emblems of pleasure while simultaneously evoking thoughts of violence, death, and dying. Delicious, luxurious, mysterious, and a bit morbid, pies were edible objects of material culture, which served many similar functions to objects of memento mori. This association between pies and death takes on a deeper resonance when we consider the many forms of conceptual, cultural, and physical violence that went into the making of an early modern pie. Tied to global commerce and containing ingredients produced by women and men held in bondage, the early modern pie becomes a potent reminder of the true cost of luxury eating in this period.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editors of this special issue, Eleanor Barnett and Katrina Mosely, as well as Rachel Herrmann and her fellow editors of Global Food History. Our thanks go as well to the anonymous reviewers of this essay, and to all members of the Before ’Farm to Table’ team at the Folger Shakespeare Library. We are grateful for your insights, expertise, and true collegiality.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Amanda E. Herbert

Amanda E. Herbert is Associate Professor of Early Modern Americas in the History Department at Durham University. She is a historian of the body: gender and sexuality, health and wellness, food, drink, and appetite.

Michael Walkden

Michael Walkden is an independent scholar based in Washington, DC. He was a postdoctoral research fellow on the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation–funded Before “Farm to Table”: Early Modern Foodways and Cultures project at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, DC from 2019 to 2021.

Notes

1. In this field, scholars have certainly considered food containers, especially high-cost, highly decorative ones like porcelain and tableware. This scholarship is vast; for just a few examples on porcelain, creamware, and other table wares in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century European contexts, see Pickman, Golden Age of European Porcelain; Jarry, Chinoiserie; Meister and Reber, European Porcelain of the 18th Century. See also the groundbreaking work by Brewer and Porter, Consumption and the World of Goods.

2. Eden, “Sometimes Food Is Just Food.”

3. On material culture and concealment and revelation, see Van Horn, The Power of Objects. On illusion and trickery, see Bellion, Citizen Spectator. On deception, see Lynch, Deception and Detection. On miniaturization, “baby houses,” and the formation of collections and souvenirs, see Greene, Family Dolls’ Houses; and Stewart, On Longing; and on postmodern consumerism and “cuteness” see Ngai, Our Aesthetic Categories. Food, objects, and death, albeit in contexts outside of the scope of this article, have been explored valuably by Ames, Death in the Dining Room; and Isenstadt, “Visions of Plenty”; see also the beautiful, thought-provoking piece by Okri, “Food, Ritual, and Death.” On objects and their movement and meaning between the Americas and Europe, see Goodman and Norberg, Furnishing the Eighteenth Century.

4. Shahani, Tasting Difference; Cevasco, Violent Appetites; Twitty, Cooking Gene.

5. On the “New Science” and navigating the spaces of the early modern British empire, see Parsons, “Natural History”; Murphy, “Collecting Slave Traders”; Bleichmar et al., Science in the Spanish and Portuguese Empires; Delbourgo and Dew, Science and Empire.

6. Woolley, Accomplish’d Ladies Delight, 128.

7. May, Accomplisht Cook, 112.

8. Simmons, American Cookery, 23; “Sea-pie, n.2,” OED Online.

9. “Pie, n.2,” OED Online. For more on this etymology, as well as an accessible and wide-ranging history of pie, see Clarkson, Pie, 14–15.

10. For an example of a pork pie, see Austin, Two fifteenth-century cookery-books, 53; for beef and fish, see Fabyan, New chronicles, ix.

11. Folger MS V.a.215, 156–157.

12. See the iconic work by Mintz, Sweetness and Power; see also Hall, “Culinary spaces, colonial spaces”; Park, “Discandying Cleopatra.”

13. Folger MS V.a.561, 230–231.

14. Folger MS W.b.653, 51.

15. Folger MS W.b.456, 121.

16. SCHS MS 43/2178, f.21 v.

17. SCHS MS 34/719, f.9 r.

18. Folger MS V.a.396, pp. 23–24. For evidence of the early modern global trade in spices, see Pearson, Spices; Freedman, Out of the East; Norton, Sacred Gifts, Profane Pleasures; Foster, Letters; De Orta, Colloquies.

19. Cook and King, A voyage to the Pacific Ocean, vol. II, 494. Cook’s entry is for 8 October, 1778. His use of “Oonalashka” is probably a reference to Unalaska, an area in the Aleutian Islands off modern-day Alaska. We don’t know who made the pie; Cook later implies that the Native man offered it on the behalf of some local Russians. While rye flour has been associated with Russian foodways, the salmon and rye loaf could equally have been made or created, either voluntarily or under duress, by Native people. On Unangax or Alutiiq people and their history, see Partnow, Making History: Alutiiq/Sugpiaq life on the Alaska Peninsula.

20. Winterthur MS Document Citation1044, f. 10 v.

21. Alan Davidson has argued that with pie, “shape governs usage,” and describes them as “a mixture of ingredients encased and cooked in pastry.” For Davidson, firm, upright sides are a defining feature of pies, although he acknowledges that there are pies without pastry tops (e.g. shepherd’s pie, which has a potato top) and pies without any top at all (e.g. sweet pies with cream or fruit fillings). Davidson, The Oxford Companion to Food, 602–603, 624.

22. Benson, Riverside Chaucer, 29.

23. Simmons, American Cookery, 25.

24. Fiennes, Through England on a side saddle, 242. According to one account, “There was a Dwarf at the Marriage of the Duke of Bavaria, who was compleatly arm’d, with a short spear, and his sword girt about him, and he was hid in a Pie that one could not see him, and he was set upon the Table, and he brake the crust of the Pie and came forth, and drawing his sword he danced like a Fencer, and made all the people laugh and admire him.” Jonstonus, History, 325. On Jeffrey Hudson, who was encased in a pie at the wedding of Charles I and Henrietta Maria, see Clarkson, Pie, 87.

25. Dickens, Nicholas Nickleby, vii. 62.

26. Alan Davidson argues that potting techniques originated in the Middle Ages in pie baking. French fat-and-jelly preservation includes confit, rillettes, and terrine. Some of these approaches do still incorporate pastry crusts, while others rely on cooking vessels to provide support for fillings. Traditional English pork pies rely on the jelly to help preserve and protect the food. Davidson, Oxford Companion to Food, 624, 630–631.

27. Folger MS V.a.20, f. 31 v.

28. Raffald, The Experienced English Housekeeper, 123.

29. Turquet de Mayerne, Archimagirus anglo-gallicus, 16.

30. Wellcome MS 1176, 19.

31. Lilly MS LMC 2435, f. 5 v.

32. Spring houses or cellars were also sometimes used to preserve food in elite homes in this period, although typically these were imagined as cold and damp rather than cold and dry. See also Pennell, The Birth of the English Kitchen.

33. Rabisha, Whole body of cookery, 18–19. The famous French chef François Pierre de la Varenne similarly declared that “Your pasties for keeping, or to carrie far off, may be made with Rie meale.” La Varenne, The French cook, 123.

34. Mayerne, Archimagirus, 15.

35. Israel Acrelius, History of New Sweden, 159.

36. Israel Acrelius arrived in Delaware in or around 1749. The first Europeans to invade Delaware were the Dutch in 1631. By the time Acrelius disembarked in Wilmington, Europeans would have been a consistent settler-colonial presence in this region for just over one hundred years. We’ve chosen to retain the term “colonizer” to signal that, for many Native as well as for many Black women and men, the continued invasive presence of Europeans in North, Central, and South America was damaging and destructive. For excellent, recent explorations of the use of “settler-colonialism” in early American history, see the articles by the participants in the 2019 WMQ forum on this topic, including Ashley Glassburn, Allan Greer, Tiya Miles, Jeffrey Ostler, Susanah Shaw Romney, Nancy Shoemaker, Stephanie Smallwood, Jennifer Spear, Samuel Truett, and Michael Witgen. For an introduction to this forum see Ostler and Shoemaker, “Settler Colonialism in Early American History,” 361–368.

37. Simmons, American Cookery, 24.

38. “Hoecake, n.,” OED Online.

39. Earle, “If You Eat Their Food …,” 688–713. Hasty pudding, long associated with early American identity, was also made with corn meal. While scholars have rightly described hasty pudding as tied to Americanness, including white Americanness, they’ve also noted in these contexts that maize nonetheless was named as “Indian corn.” See for example Lemay, “The Contexts and Themes of ‘The Hasty-Pudding,’” 3–23; and Zafar, “The Proof of the Pudding,” 133–49.

40. Koehler, “Hostile Nations,” 427–453 (quote on 440).

41. Twitty, Cooking Gene, 72, 210, 214.

42. On Amelia Simmons and how her cookbook was situated as a product of New England and its culture and literature, see Stavely and Fitzgerald, United Tastes; on the prevalence of the enslavement of Indigenous and Black women, men, and children in colonial New England, see Warren, New England Bound.

43. Wondrausch, “Potted Char,” 229.

44. Ibid.

45. Ibid.

46. Anon., Whole Duty of a Woman, 570–1.

47. Huntington MS HA 5738.

48. Huntington MS HA 1751.

49. Huntington MS HA 1775.

50. Huntington MS HA 8223.

51. Bodleian MS Radcliffe c. 1., f. 29. Thanks to Oliver House at the Bodleian Library for making a digital copy of this letter available.

52. Ibid.

53. Ibid.

54. Werrett, Thrifty Science; Werrett, “Food, Thrift, and Experiment.” On intellectual and creative endeavor in the early modern kitchen see especially Wall, Recipes for Thought.

55. Heylyn, Cyprianus anglicus, 320. See also Carlyle, Historical Sketches, 98–99.

56. Rycaut, Present state, 86.

57. May, Accomplisht cook, sig. A8r. Wendy Wall points out that such “counterfeit foods” as May’s pie also functioned as an exploration of the boundary between nature and culture: “Surprising diners with pies housing live creatures is designed to evoke a sheer sense of marvel about the quandary of definitively separating ‘food’ from an animate natural world.” Wall, Recipes for Thought, 79–80.

58. Ray, English proverbs, 79.

59. Webster, White diuel, sig. G3r.

60. “Coffin, n.,” OED Online.

61. Rabisha, Whole body of cookery, 22.

62. Folger MS V.a.434, f. 15 r.

63. Rabisha, Whole body of cookery, 22.

64. May, The Accomplisht Cook, 303.

65. May, The Accomplisht Cook, 241.

66. Goeimare, View of the interior of a lavishly stocked kitchen.

67. Monsieur Marnettè, The perfect cook (London, 1656). On eating peacocks and images of peacock pies, see Elisa Tersigni, “Before the Thanksgiving turkey came the banquet peacock.”

68. “Many people are busy in the baker’s kitchen preparing cakes, pastries, pies and bread,” n.d., Wellcome Collection 31301i. Plate from Diderot and d’Alembert, Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences. Catalogue notes state that this copy of the plate also includes the text, “Pattisier, tour à pâte, bassines, mortier &c. Benard fecit.” The full title of Diderot and d’Alembert’s famous text can be translated as “Encyclopedia or a Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Tradecrafts, by a Society of Men of Letters.”

69. Dekker, The pleasant comodie of patient Grisill. This text is unpaginated, but the quote appears near sig. J2.

70. Breton, Fantasticks, sig. B4r.

71. Jonson, The Staple of the News, 21. Quote appears in Act II, Scene I, Line 18. This play was first performed in 1625 and first published in 1631.

72. Mowat et al, Titus Andronicus, Act V, Scene 3, Line 61.

73. W. S., The puritaine or The widow of Watling-streete. This text is unpaginated, but the quote appears in gathering A. The title page of this work records the author as “W. S.” which led some to speculate that it belongs to Shakespeare; this has been disproved and the play is most often attributed to Thomas Middleton. See Kirwan, “The Puritan, first edition.”

74. Heywood, Gynaikeion, 444.

75. As Wall notes, the early modern kitchen “was spacious enough to embrace the work of recycling corpses,” a form of work which invariably “placed the human body imaginatively in proximity to death, carnality, and orality.” Wall, Staging Domesticity, 197.

76. For just a few examples, see Llewellyn, Art of Death; Brown, Reaper’s Garden; Cressy, Birth, Marriage, and Death; Laqueur, Work of the Dead; Tomaini, Dealing with the Dead.

77. Booy, Notebooks, 271.

78. Ibid.

Bibliography

- Archival Sources

- Bodleian Library, Oxford UK

- Bodleian MS Radcliffe c. 1. “Robert Uvedale (Enfield, Middlesex) to Richard Richardson (Bierley, W. Yorkshire).” 30 Aug 1700.

- Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington, D.C.

- Folger MS V.a.20. “Cookbook of Constance Hall.” 1672.

- Folger MS V.a.215. “Cookbook of Susanna Packe.” c. 1674.

- Folger MS V.a.396. “Receipt Book of Penelope Jephson.” 1671, 1674/5.

- Folger MS V.a.434. “Cookbook of Ann Smith.” 1698.

- Folger MS V.a.561. “Cookeries.” Late 17th century.

- Folger MS W.b.456. “Cookery Book of Lettis Vesey.” c. 1725.

- Folger MS W.b.653. “Cookbook.” c. 1720.

- Huntington Library, San Marino CA

- Huntington MS HA 1751. Hastings Collection, Box 22 HA 1751. “Beatrix Clerke, Letter to Theophilus Hastings (7th Earl Huntingdon).” 18 March 1661.

- Huntington MS HA 1775. Hastings Collection, Box 36 HA 1775. “Bridget Croft, Letter to Theophilus Hastings (7th Earl Huntingdon).” 1673.

- Huntington MS HA 5738. Hastings Collection, Box 17 HA 5738. “Lucy (Davies) Hastings (Countess of Huntingdon), Letter to Lord [Ferdinando] Hastings (6th Earl Huntingdon).” 1650.

- Huntington MS HA 8223. Hastings Collection, Box 43 HA 8223. “Mary Lewis Leke (Countess Scarsdale). Letter to her sister Elizabeth Lewis Hastings (Countess Huntingdon).” c.1682.

- Lilly Library, Bloomington, IN

- Lilly MS LMC 2435. “Macie’s Booke.” 1691.

- Wellcome Library, London

- Wellcome A629458. “A Memento Mori Statue, Used to Remind the User of the Transience of Life and Material Luxury, Containing a Decaying Corpse Inside a Coffin.” Possibly Italy, 1501–1600.

- Wellcome A641823. “A Gold Memento Mori Pendant, Used to Remind the User of the Transience of Life and Material Luxury, Containing a Decaying Corpse Inside a Coffin. Open.” n.d.

- Wellcome MS 1176. “Hannah Bisaker Her Book [Of Cookery Receipts].” 1692.

- South Carolina Historical Society, Charleston, SC

- SCHS 34/719. “Mrs. William Timmons Receipt Book.” 1831.

- SCHS 43/2178. “Eliza Pinckney Receipt Book.” 1756.

- Winterthur Museum, Winterthur, DE

- Winterthur MS Document 1044. “Recipe Book of Elizabeth Coultas.” 1749–1750.

- Published Sources

- Acrelius, Israel. A History of New Sweden; Or, the Settlements on the Delaware River, Translated William M. Reynolds. Philadelphia: Memoirs of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1874.

- Ames, Kenneth L. Death in the Dining Room and Other Tales of Victorian Culture. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1992.

- Anon. The Whole Duty of a Woman, Or, An Infallible Guide to the Fair Sex. London: printed for T. Read, in Dogwell-Court, White-Fryers, Fleet-Street, 1737.

- Anon. unsigned, PATISSIER, Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, etc, Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d’Alembert. University of Chicago: ARTFL Encyclopédie Project ( Autumn 2022 Edition), Robert Morrissey and Glenn Roe (eds): https://encyclopedie.uchicago.edu. Accessed on 29 July, 2023).

- Anon. “Many People are Busy in the Baker’s Kitchen Preparing Cakes, Pastries, Pies and Bread,” n.d. Wellcome Collection 31301i.

- Austin, Thomas ed. Two fifteenth-century cookery-books : Harleian ms. 279 (ab. 1430), & Harl. ms. 4016 (ab. 1450), with extracts from Ashmole ms. 1429, Laud ms. 553, & Douce ms. 55. London: N. Trübner & Co, 1888.

- Bellion, Wendy. Citizen Spectator: Art, Illusion, & Visual Perception in Early National America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011.

- Benson, Larry D., ed. The Riverside Chaucer. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

- Bleichmar, Daniela, Paula De Vos, Kristin Huffine, and Kevin Sheehan, eds. Science in the Spanish and Portuguese Empires. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2009. doi:10.1515/9780804776332.

- Booy, David, ed. Notebooks of Nehemiah Wallington, 1618-1654: A Selection. Farnham: Ashgate, 2007.

- Breen, T. H. The Marketplace of Revolution: How Consumer Politics Shaped American Independence. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Breton, Nicolas. Fantasticks Seruing for a Perpetuall Prognostication. London: Printed [by Miles Flesher] for Francis Williams, 1626.

- Brewer, John, and Roy Porter. Consumption and the World of Goods. London: Routledge, 1993.

- Brown, Vincent. The Reaper’s Garden: Death and Power in the World of Atlantic Slavery. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2008.

- Carlyle, Thomas. Historical Sketches of Notable Persons and Events in the Reigns of James I. and Charles I. London: Chapman and Hall Limited, 1898.

- Cevasco, Carla. Violent Appetites: Hunger in the Early Northeast. New Haven CT: Yale University Press, 2022.

- Clarkson, Janet. Pie: A Global History. London: Reaktion Books, 2009.

- Coffin, n. OED Online, June 2021, Oxford University Press. https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/35802 (accessed August 31, 2021).

- Cook, James, and James King. A Voyage to the Pacific Ocean. London: printed by H. Hughes, for G. Nicol; and T. Cadell, 1785.

- Cressy, David. Birth, Marriage, and Death: Ritual, Religion, and the Life-Cycle in Tudor and Stuart England. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

- Davidson, Alan. The Oxford Companion to Food. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Dekker, Thomas. The Pleasant Comodie of Patient Grisill. London: Imprinted [by E. Allde] for Henry Rocket, 1603.

- Delbourgo, James, and Nicholas Dew. Science and Empire in the Atlantic World. New York: Routledge, 2008. doi:10.4324/9780203933848.

- De Orta, Garcia. Colloquies on the Simples & Drugs of India. London: Henry Sotheran and Co, 1913.

- Dickens, Charles John Huffam. The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby. London: Chapman and Hall, 1839.

- Eacott, Jonathan. Selling Empire: India in the Making of Britain and America, 1600-1800. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016.

- Earle, Rebecca. “‘If You Eat Their Food … ’: Diets and Bodies in Early Colonial Spanish America.” The American Historical Review 115, no. 3, June (2010): 688–713. doi:10.1086/ahr.115.3.688.

- Eden, Trudy. “Sometimes Food is Just Food.” Reviews in American History 42, no. 3, September (2014): 393–397. doi:10.1353/rah.2014.0072.

- Fabyan, Robert. New Chronicles of England and France, edited by Henry Ellis. London: Printed for F.C. & J. Rivington [etc.], 1811.

- Fiennes, Celia. Through England on a Side Saddle: In the Time of William and Mary. London and New York: Field & Tuer, The Leadenhall Press, E.C. Simpkin, Marshall & Co.; Hamilton, Adams & Co. Scribner & Welford, 1888.

- Foster, William, ed. Letters Received by the East India Company. London: Sampson Low, Marston & Company, 1902.

- Freedman, Paul. Out of the East: Spices and the Medieval Imagination. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008.

- Goeimare, Joos. View of the Interior of a Lavishly Stocked Kitchen. Venice, 1650–1687.

- Goodman, Dena, and Kathryn Norberg. Furnishing the Eighteenth Century: What Furniture Can Tell Us About the European and American Past. New York: Routledge, 2007. doi:10.4324/9780203943458.

- Greene, Vivien. Family Dolls’ Houses. London: G. Bell & Sons, 1973.

- Hall, Kim F. “Culinary Spaces, Colonial Spaces: The Gendering of Sugar in the Seventeenth Century.” In Feminist Readings of Early Modern Culture: Emerging Subjects, edited by Valerie Traub, Lindsay M. Kaplan, and Dympna Callaghan, 168–190. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- Heylyn, Peter. Cyprianus Anglicus, Or, the History of the Life and Death …. London: Printed for A. Seile, 1668.

- Heywood, Thomas. Gynaikeion [Γυναικεῖον]: Or, Nine Bookes of Various History Concerninge Women. London: Printed by Adam Islip, 1624.

- Hoecake, n. OED Online, June 2021, Oxford University Press. https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/87563 (accessed July 31, 2021).

- Isenstadt, Sandy. “Visions of Plenty: Refrigerators in America Around 1950.” Journal of Design History 11, no. 4 (1998): 311–321. doi:10.1093/jdh/11.4.311.

- Jarry, Madeleine. Chinoiserie: Chinese Influence on European Decorative Art 17th and 18th Centuries. New York: The Vendome Press for Sotheby Publications, 1981.

- Jonson, Benjamin. The Workes of Benjamin Jonson…. London: Printed for Richard Meighen, 1640.

- Jonstonus, Joannes. An History of the Wonderful Things of Nature Set Forth …. London: Printed by John Streater … , and are to be sold by the Booksellers of London, 1657.

- Kirwan, Peter. “The Puritan, First Edition.” Shakespeare Documented (accessed July 30, 2023). doi:10.37078/223.

- Koehler, Rhiannon. “Hostile Nations: Quantifying the Destruction of the Sullivan-Clinton Genocide of 1779.” American Indian Quarterly 42, no. 4 (2018): 427–453. Fall 2018. doi:10.5250/amerindiquar.42.4.0427.

- La, Varenne, and François Pierre. The French Cook. Prescribing the Way of Making …. London: Printed for Charls Adams, 1653.

- Laqueur, Thomas W. The Work of the Dead: A Cultural History of Mortal Remains. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2015.

- Lemay, J.A. Leo. “The Contexts and Themes of ‘The Hasty-Pudding.’” Early American Literature 17, no. 1 (1982): 3–23.

- Llewellyn, Nigel. The Art of Death: Visual Culture in the English Death Ritual, C. 1500-C. 1800. London: Reaktion Books, 1991.

- Lynch, Jack. Deception and Detection in Eighteenth-Century Britain. London: Routledge, 2008.

- Marnettè, Monsieur. The Perfect cook. London: Printed for Obadiah Blagrave at the Black Bear and Star in St. Pauls Church-yard, over against the Little North Door, 1686.

- May, Robert. The Accomplisht Cook, or the Art and Mystery of Cookery: Wherein the Whole Art …. London: Printed by R.W. for Nath. Brooke, 1660.

- May, Robert. The Accomplisht Cook, or the Art and Mystery of Cookery: Wherein the Whole Art …. London: Printed for Obadiah Blagrave, 1685.

- Meister, Peter Wilhelm, and Horst Reber. European Porcelain of the 18th Century. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1983.

- Mintz, Sidney. Sweetness and Power. New York: Penguin, 1985.

- Shakespeare, William. Titus Andronicus, edited by Barbara Mowat, Paul Werstine, Michael Poston, and Rebecca Niles. Washington, DC: Folger Shakespeare Library. n.d. https://shakespeare.folger.edu/shakespeares-works/titus-andronicus. Accessed August 27, 2021.

- Murphy, Kathleen S. “Collecting Slave Traders: James Petiver, Natural History, and the British Slave Trade.” The William and Mary Quarterly. 70, no.4 (2013):637–670. doi:10.5309/willmaryquar.70.4.0637.

- Ngai, Sianne. Our Aesthetic Categories: Zany, Cute, Interesting. Harvard: Harvard University Press, 2015.

- Norton, Marcy. Sacred Gifts, Profane Pleasures: A History of Tobacco and Chocolate in the Atlantic World. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2008.

- Norton, Mary Beth. “The Seventh Tea Ship.” The William and Mary Quarterly 73, no. 4 (2016): 681–710. doi:10.5309/willmaryquar.73.4.0681.

- Okri, Ben. “Food, Ritual, and Death.” Callaloo 38, no. 5 (2015): 1034–1036. doi:10.1353/cal.2015.0153. Fall.

- Ostler, Jeffrey, and Nancy Shoemaker. “Settler Colonialism in Early American History: Introduction.” The William and Mary Quarterly 76, no. 3 (2019): 361–368. doi:10.5309/willmaryquar.76.3.0361.

- Park, Jennifer. “Discandying Cleopatra: Preserving Cleopatra’s Infinite Variety in Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra.” Studies in Philology 113, no. 3 (2016): 595–633. doi:10.1353/sip.2016.0023.

- Parsons, Christopher. “The Natural History of Colonial Science: Joseph-François Lafitau’s Discovery of Ginseng and Its Afterlives.” The William and Mary Quarterly. 73, no.1 (2016):37–72. doi:10.5309/willmaryquar.73.1.0037.

- Partnow, Patricia H. Making History: Alutiiq/Sugpiaq Life on the Alaska Peninsula. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press, 2001.

- Pearson, M. N. ed. Spices in the Indian Ocean World. New York: Routledge, 1996.

- Pennell, Sara. The Birth of the English Kitchen, 1600-1850. London: Bloomsbury, 2016. doi:10.5040/9781474217743.

- Pickman, Dudley Leavitt. The Golden Age of European Porcelain. Boston: Plimpton Press, 1936.

- Pie, n.2. OED Online, June 2021, Oxford University Press. https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/143537 (accessed July 27, 2021).

- Rabisha, William. The Whole Body of Cookery …. London: Printed by R. W. for Giles Calvert, 1661.

- Raffald, Elizabeth. The Experienced English Housekeeper. London: printed by J Harrop, 1769.

- Ray, John. A Collection of English Proverbs Digested into a Convenient Method for the Speedy Finding … Cambridge: Printed by John Hayes, for W. Morden, 1678.

- Rycaut, Paul. The Present State of the Ottoman Empire Containing the Maxims of the Turkish Politie. … London: Printed for John Starkey and Henry Brome, 1668.

- Shahani, Gitanjali. Tasting Difference: Food, Race, and Cultural Encounters in Early Modern Literature. Ithaca NY: Cornell University Press, 2022.

- Simmons, Amelia. American Cookery, or the Art of Dressing Viands, Fish, Poultry, and Vegetables. … Hartford: Printed for Simeon Butler, 1798.

- Stavely, Keith, and Kathleen Fitzgerald. United Tastes: The Making of the First American Cookbook. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2017.

- Stewart, Susan. On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection. Durham NC: Duke University Press, 1992.

- Sweeney, Shauna. “A Free Enterprise: Market Women, Insurgent Economies and the Making of Caribbean Freedom,” forthcoming.

- Tersigni, Elisa. “Before the Thanksgiving Turkey Came the Banquet Peacock.” Shakespeare & Beyond, Folger Shakespeare Library, November 6, 2020. https://www.folger.edu/blogs/shakespeare-and-beyond/before-the-thanksgiving-turkey-came-the-banquet-peacock/. Accessed August 2, 2023.

- Tomaini, T., ed. Dealing with the Dead: Mortality and Community in Medieval and Early Modern Europe. Leiden: Brill, 2018. doi:10.1163/9789004358331.

- Turquet de Mayerne, Théodore. Archimagirus Anglo-Gallicus: Or, Excellent & Approved Receipts and Experiments in Cookery. Together with the Best Way of Preserving…. London: Printed for G. Bedell, and T. Collins, 1658.

- Twitty, Michael W. The Cooking Gene: A Journey Through African American Culinary History in the Old South. New York: Harper Collins, 2017.

- Van Horn, Jennifer. The Power of Objects in Eighteenth-Century British America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017. doi:10.5149/northcarolina/9781469629568.001.0001.

- Wall, Wendy. Staging Domesticity: Household Work and English Identity in Early Modern Drama. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- Wall, Wendy. Recipes for Thought: Knowledge and Taste in the Early Modern English Kitchen. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015. doi:10.9783/9780812291957.

- Warren, Wendy. New England Bound: Slavery and Colonization in Early America. New York: W.W. Norton, 2017.

- Webster, John. The White Diuel, Or, the Tragedy of Paulo Giordano Vrsini, Duke of Brachiano … London: Printed by N[icholas] O[kes] for Thomas Archer, and are to Be Sold at His Shop in Popes Head Pallace, Neere the Royall Exchange, 1612.

- Werrett, Simon. Thrifty Science: Making the Most of Materials in the History of Experiment. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019. doi:10.7208/chicago/9780226610399.001.0001.

- Werrett, Simon. “Food, Thrift, and Experiment in Early Modern England.” Global Food History (2021): 1–17. doi:10.1080/20549547.2021.1942666.

- Wilson, Kathleen. A New Imperial History: Culture, Identity, and Modernity in Britain and the Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Wondrausch, Mary. “Potted Char.” In Disappearing Foods: Studies in Foods and Dishes at Risk: Proceedings of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery 1994, edited by Harlan Walker, 227–234. Totnes: Prospect Books, 1995.

- Woolley, Hannah. The Accomplish’d Ladies Delight in Preserving, Physick, Beautifying, and Cookery … London: Printed for Benjamin Harris, at the Stationers Arms and Anchor, in the Piazza, at the Royal-Exchange in Cornhill, 1684.

- Zafar, Rafia. “The Proof of the Pudding: Of Haggis, Hasty Pudding, and Transatlantic Influence.” Early American Literature 31, no. 2 (1996): 133–149.