ABSTRACT

The Salt Lake (or Mormon) Tabernacle in Salt Lake City, Utah has been the object of religious, scientific, and cultural fascination since its construction in the 1860s. To this day, visitors are treated to a pin-drop performance that demonstrates the building’s unique acoustic properties. The building, whose history stretches from pioneer auditorium to broadcasting facility, has anchored a cross-generational soundscape that is at once architectural, musical, oratorical, political, and religious. Its soundscape echoes well over a century with both choral hymns and physical, even metaphysical silences. This article traces the story of that soundscape and demonstrates the relevance of the history of ideas as a method in sound studies.

“God is manifest in his works, ordinances, and institutions, and in his own buildings.”

Orson Pratt, “On the Dedication of the New Tabernacle” (1875)

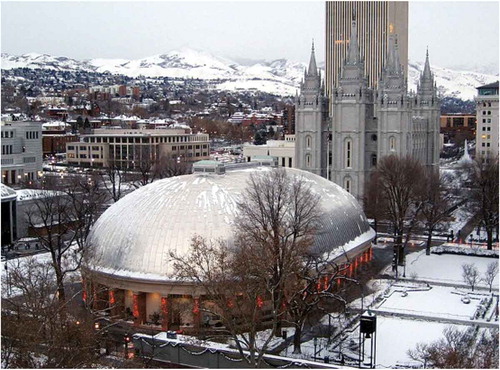

Figure 1. The tabernacle (front) and temple (rear) on temple square, Salt Lake City, Utah, 2008. CC BY SA, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:S.L._Tabernacle_on_temple_square.jpg

Chronic sound

Every philosophical discussion of sound invites a mention of Hegel’s endlessly provocative dictum that a tone is a “Daseyn das verschwindet, in dem es ist.” Sound exists in disappearance or disappears in existence – however you translate it, Hegel’s saying stresses the unstoppable evanescence of sound as a passenger on time’s one-way arrow. Typically when we think about sound’s relationship to time, we think of it as kairos, as a momentary opening or opportunity, rather than as chronos, ongoing duration. Could we conceive of sound as chronic and enduring rather than decaying? Is that mental exercise even possible? “Forever – is composed of Nows – ” wrote the highly musical poet Emily Dickinson and we cannot miss the pun in the term “composed.” The sustaining of an acute single sound would require constant refreshing; a chronic sound could only be the sum of many acute ones.

Here I want to consider a different kind of cross-generational preservation of sound. There are many examples of sounds that outlast generations; most notably, language is a system that no single individual ever fully controls but exercises more or less consistent pressure on the oral musculature of speakers over centuries, with obvious and fascinating sound shifts, some fast, and some slow. Vowels, which are enormously complex phonological objects, are passed on between generations with slight variations. In this paper, I explore the preservation of sounds and styles of audition across generations in the Salt Lake Tabernacle, built in the 1860s by Latter-day Saint pioneers, members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, as part of a hierocentric city plan that included a massive temple, finished only in 1893 (see ). At least, the Tabernacle records the possibilities of such sounds. It is a hybrid object saturated with theories about sound the same way that musical instruments, even when not played, are. Ideas about sound are a key material for sound studies; indeed, ideas are one of the ways that sounds can outlast the moment of their production, making intellectual history a key method in sound studies. The Tabernacle, I will argue, specialises in sounds that both call up cross-generational memory and hover on the edge of sheer silence.Footnote1

Theophany and theophony

Architectural acoustics has an old theological imagination. Sacred sounds were arguably a key part of archaic human activities in caves (Blesser and Salter Citation2007, 73–78). Classical theatres, about which the Roman architectural theorist Vitruvius (Citation1999, book, 5) provides such interesting data, were designed to make audible and visible the doings of gods and heroes to the people. (Other open-air assembly spaces, in contrast, were designed to make the voices of the people audible to themselves.) The people of Athens dedicated their large amphitheatre to Dionysus, the god of epiphany. Greek and Roman theatres, then, were made for the showing and voicing of deities. Martin Heidegger called Greek theatre Götterschau – roughly, the showing of the gods (quoted in Kittler Citation2009, 40) – but why couldn’t we also think of it as Götterklang, the sound of the gods? Theophany, meaning the visible manifestation of deity, needs perhaps a new companion term for the auditory manifestation; I propose theophony. What could be better examples of sonic things than these elusive and layered objects?

Oddly, among the many disciplines in R. Bruce Lindsay’s well-known “wheel of acoustics,” theology is missing, even though so many figures in the history of acoustics, from Archytas, Marin Mersenne, and Athanasius Kircher to Leonhard Euler and Harvey Fletcher, were fascinated by questions of how divine voices are made manifest. Kircher studied acoustics and optics with the express purpose of sounding God’s voice and showing the magic of his power. Indeed, the spectacular manipulation of sound and light has long been important in diverse religious ceremonies, leading to rich disputes in the early modern era, for instance, about whether “sacramental technologies” were devices of fraud for manipulating the credulous or metaphors for channelling the divine (Schmidt Citation2000). This paper takes media technologies of sound, including architecture, as constitutive of, not alien to, religious experience (Meyer Citation2011). Good sound can transport you to other worlds. As Patel and Bassuet (Citation2012), acoustic engineers at Arup, put it with becoming accuracy and frankness: “transcendence is our business.”

Media houses

The mix of transcendence and business is found in buildings that serve as headquarters for media institutions, buildings that are themselves heirs of ancient, medieval, and early modern edifices designed to show forth the power of polity and deity. The innovative book Media Houses, edited by Ericson and Riegert (Citation2010), provides case studies of “broadcast temples” such as the BBC’s Broadcasting House in London, the Ostankinskaya TV Tower in Moscow, the Googleplex in Mountain View, the CCTV building in Beijing, and the IAC Building in New York. Such buildings show a strange interplay between materiality and immateriality in being site-specific structures that nonetheless represent the spatial dispersion of ethereal substances such as sounds, images, and data. Media houses follow an older legacy of religious buildings by both concentrating political-economic power and emanating quasi-divine entities through heaven and earth.

The Salt Lake Tabernacle belongs to a different moment, but it too is a media house. Built exactly 100 years before the Ostankinskaya Tower, in 1863–67, the Tabernacle was historically treated by Latter-day Saint culture as an acoustically sensitive voice box, a container and disseminator of prophetic sound in air, print, and broadcasting. It is an interesting case study for several reasons. First, the building embodies a theology of the amplified and the muted voice that, though not unique to Mormonism, is freshly articulated in the tradition. Second, it has been the object of a theological tradition of imagining kinds of assembly that are both physically present and diasporically scattered. Third, it anchors a ghostly sonic link with the pioneers who built it in the nineteenth century under some duress. Fourth, it focalises a particular tradition of religious reflection about spiritual audition. Good sound is a religious matter in Mormonism, and for well over a century, from 1867 to 1999, anything that mattered was said in the Tabernacle. It served as the acoustic centre-point of a global religion. The Tabernacle is a media house whose aesthetics follows from the god it serves, as Vitruvius (Citation1999, 14) says every shrine does. Its story is one of wind, lungs, weather, animal parts, politics, choirs, prophets, and the voice of God.

Theotechnics of sound in Mormonism

There were many tabernacles built in the first three decades after the Church’s founding in 1830. Forced migration enabled architectural experimentation, and tabernacles of various designs and materials – log, canvas, adobe – were built in Ohio, Illinois, Nebraska, and Utah once the Latter-day Saints arrived there in 1847 (Roberts Citation1975; Watson Citation1979). Perhaps not since the first meeting of the Church, in April 1830 in a house in upstate New York, have all the members been able to gather in a singular physical spot. This has meant a religious tradition committed to both virtual community at a distance and pilgrimage to gathering spots. Mormonism’s intense geographical imagination and demographic dispersion have funded a theotechnics of assembly and pilgrimage that imbues the Tabernacle (Howlett Citation2014; Eyring Citation2016). By theotechnics I understand, expansively, the cultural techniques that produce the divine or the cultural techniques used by divinity (Peters Citation2015a, 372).

From the beginning, concerns about virtual assembly have been acoustic. The idea that God’s voice must go forth is one well founded in both Jewish and Christian traditions (see, for instance, Psalm 19:4, repurposed by Paul of Tarsus in Rom. 10:18). But the Mormon tradition took a particular interest in how to carry voices across distance and numbers. “The sound must go forth from this place unto all the world,” Smith announced in 1831 (Doctrine and Covenants 58:64). The Book of Mormon, first published in 1830, features several episodes of large-scale outdoors vocal address. The ageing King Benjamin, for instance, convokes his people to give his valedictory address. “And it came to pass that he began to speak to his people from the tower; and they could not all hear his words because of the greatness of the multitude; therefore he caused that the words which he spake should be written and sent forth among those that were not under the sound of his voice, that they might also receive his words” (Mosiah 2:8). (Nobody seems concerned about dilution or deletion in this oral–literate relay.) The prophet Alma divides his people into groups led by different teachers since “neither could they all hear the word of God in one assembly” (Mosiah 25:20). An unamplified voice before a large audience required a technical work-around of some kind. Voice media abound in The Book of Mormon (McMurray Citation2015).

Church founder Joseph Smith’s early revelations also show a special interest in the technical aspects of vocal delivery. A revelation from 1832–33 dictates that the presiding teacher “shall be first in the house of God, in a place that the congregation of the house may hear his words carefully and distinctly, not with loud speech.” These instructions about audible speaker placement are now canonised Mormon scripture and informed the Church’s first major building project, the Kirtland temple, a building with a barrel-vaulted ceiling that was designed with some acoustic care; they prize auditory clarity over vocal exertion. The point was for the “school of the prophets,” as Smith called it, to “become a sanctuary, a tabernacle of the Holy Spirit to your edification” (Doctrine and Covenants, 88:129, 137). The first use of “tabernacle” in Smith’s revelations went with instructions about architectural acoustics.

But Smith also had grander ideas about the tabernacle concept, declaring in one of his boldest pronouncements: “The elements are the tabernacle of God; yea, man is the tabernacle of God” (Doctrine and Covenants 93:35). These words conceive tabernacle as an elemental dwelling-place for intelligence or spirit; for Smith the term was a kind of body before it was a building. Even when it came to refer to edifices, the corporeal sense of “tabernacle” remained strong (Park Citation2010). This is clear in another early revelation, featuring a complex conceit in which “the veil of the covering” of the tabernacle that hides the earth will one day be removed and “all flesh” will see the Lord together (Doctrine and Covenants 101:23). Smith uses here an almost erotically intimate language for theophany that borrows both from Exodus’s description of the holy of holies in the tabernacle and the literally apocalyptic image of the people of God as the bride of Christ, the groom who will lift the veil (in Greek, apocalypse means uncovering). However one reads this conceit, my point is that the concept of tabernacle in Mormon thought always implies a dialectic of clothing and disclosing, and that it can span the apparent mundaneness of audibility and the sublimity of God’s body. These are matters – and spirits – that are theotechnical in the deepest sense.

The voice under elemental duress

Hearing, as Schmidt has shown (Citation2000), is a domain of rich religious resonance, but Mormonism has a special investment in it (Harris and McMurray Citation2017). The movement began with a vocal adventure in approaching God. In 1820 the young Smith went to the forest near his home in Palmyra, New York to pray. Upset by the religious commotion in his family and community, he reports that “amidst all my anxieties I had never as yet made the attempt to pray vocally.” As soon as he began, he felt seized by an enemy power that “had such an astonishing influence over me as to bind my tongue so that I could not speak” (Smith Citation1838, 1, 14–15). He held on for dear life and had what is called “the first vision”: Satan binds the tongue, but when God appears, Smith can speak again. That it is hazardous to vocalise outdoors and that the presence of God alters the voice were some of the first lessons of Mormonism.

Here Smith underwent the classic ordeal of prophetic stammering (see Shell Citation2006) and for years he was a diffident public speaker, Sidney Rigdon, an early convert and fiery former minister, serving as Aaron to his Moses. By the time of his assassination in 1844, Smith was an accomplished orator. Like many speakers and singers in the nineteenth century, he had to learn to speak to assemblies numbering thousands. Many contemporaries observed how vocal styles changed to adapt to larger concert halls in the nineteenth century, but most of Smith’s speaking took place out of doors. “I do not know when I shall have the privilege of speaking in a house large enough to convene the people. I find my lungs are failing with continual preaching in the open air to large assemblies,” he lamented to an 1843 gathering in Nauvoo, Illinois (quoted in Roberts Citation1974, 401). Smith also listed “fierce winds” as a potential horror in a famous letter and though it is likely a nautical metaphor, it also fits the plight of the outdoor orator (Doctrine and Covenants, 122:7).

The theme of the voice versus the elements climaxed in Smith’s last major sermon in 1844, a funeral address for a man named King Follett. The sermon is famous for the theological audacity of claiming a continuity between human and gods, but a less noted aspect is the physical drama of its delivery to a large crowd, estimated by one observer to be ten thousand people, atop a bluff overlooking the Mississippi River. On a blustery April day, Smith asked the assembly to listen intently and to pray that the Lord would stay the winds and strengthen his lungs. He needed breath, he said, to talk about the eternal nature of spirit and element. The medium of his talk – ruach, pneuma, spiritus, atman, breath, spirit – was both its message and its rival. The urgency of so much to say, so little time, so vast a vision, so human a receptacle were matched by the performance of his struggling voice. That the discourse was delivered less than three months before he was killed also gives it a kind of testamentary status. At both ends of his prophetic career, Smith found his voice when nearing the divine in dire competition with other forces, supernatural or natural, that would muffle and dampen it. The King Follett discourse is the founding event of the drama of Mormon broadcasting, with the prophetic voice and the wind engaging in a contest of amplification and audibility (Peters Citation2015b, 413–14).

The rigours of oratorical delivery to large groups out of doors are notorious – the aged Sophocles allegedly died from overdoing his vocal exercises. Speakers have long complained about – or competed with – the elements, as Demosthenes did the sea. In the Mormon case, these complaints were the direct inspiration for a series of built spaces for the propagation of sound.

Building the tabernacle

The Salt Lake Tabernacle is the only tabernacle in Mormon architecture with an elliptical design. The first plans for elliptical auditoriums date to the 1630s, including one by the seventeenth-century acoustic pioneer Marin Mersenne, though architectural ideas about the propagation of sound appear in the Quattrocento (Barbieri Citation1998, 271–82). Kircher’s Phonurgia Nova (Citation1673, 92–102) addresses the acoustics of elliptical designs, depicting sounds as linear rays. Another key source is Pierre Patte (Citation1782) synthetic work on the optics and acoustics of theatres, which discusses elliptical buildings at length (and warns against confounding them with ovoidal shapes). Romantic ideas of acoustic enchantment fit the Tabernacle suggestively as well (Clarke Citation2015).

But it is not likely that theoretical knowledge shaped the design; its architects were steeped instead in artisanal traditions. Brigham Young had visited St. Paul’s Cathedral in London at least three times and bought an architectural guide to it; the Tower of London may echo in the temple’s castellated Gothic Revival design with its corner towers and three-tiered walls (Hamilton Citation1983, 30, 38–39). London’s large train sheds were the Tabernacle’s closest equivalent for large roofs unsupported by columns (Robison and Randall Dixon Citation2014, 22). The entire church leadership, including the three members of the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, had all been in England, and Utah swarmed with immigrants from the British Isles and elsewhere. Though geographically cloistered in the Mountain West, Mormonism partook of cosmopolitan trends. The builder of the organ, for instance, Joseph Harris Ridges, was a British convert who came to Utah via Australia and scouted organ design in Boston in the 1860s. Starting in the mid nineteenth century, most major industrial cities built a concert hall, typically with a massive, expensive organ, and Salt Lake City was no exception apart from being hardly either major or industrial at that point. Though the shape of the Tabernacle organ is iconic and adorns, for instance, the church’s hymnal, similar organ designs abound from the same period, as I noticed in a visit to the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam (completed 1888). What seems culturally unique is often just a holdover from a larger forgotten history.

The Tabernacle has a foundation of forty-four sandstone columns around its perimeter, quarried in Red Butte Canyon to the east of Salt Lake City. Little metal was used due to cost and availability; at first the building was more animal and vegetable than mineral. A dowel and wedge construction technique joined the intricate lattice wood construction of the roof, with the girders curved by steam and green rawhide wrapping the wood where the beams split. Over one million board feet of lumber were required. Bubbling vats of melting animal hides on site supplied the immense amounts of glue required for building the organ. The ceiling plaster has cattle hair in it, which has a fortunately sound-absorbing property but, where unevenly mixed, led to cracking later. The animal components of the building are an almost obsessive part of its lore. Rawhide, glue, hair: these elements build in a note of animal sacrifice, a biological contribution to the edifice, along with the wood, stone, and sweat. The materials of the building mix the biblical sacred and the cowboy profane, cattle culture being the common denominator.

The finished building is 150 by 250 feet by 80 feet high at the highest point of the roof (measured from outside; the highest point from floor to ceiling is 68 feet). It was probably the largest auditorium in North America when built, and certainly the largest without internal supporting columns. It is the child of four designers: Brigham Young, who came up with the concept of an elliptical assembly hall while sick in bed; William H. Folsom, the original architect; Henry Grow, a bridge-builder responsible for the distinctive roof; and Young’s brother-in-law, Truman O. Angell, a church architect responsible for woodwork, décor, and acoustic improvements, including the balcony/galleries, built in 1869–70 to improve seating capacity but also improving the sound immensely (Grow Citation2005). Constant tinkering was still required to eliminate echoes with curtains, garlands, canopies, and wires hung from the ceiling. As with all auditoriums before the twentieth century, the Tabernacle was designed not by equations but by empiricism – and by adjustments. The roof is the key to the building’s acoustics, but without the gallery added in 1870 and subsequent fixes, the sound would be too scattered.

The building was officially dedicated in 1875 and has had a dynamic history since. The organ grew from 700 pipes in 1867 to 11,623 pipes by 1948; the roofing went from shingle to copper sheeting to aluminium; heating, gaslight then electrical lighting, a sprinkler system for fire extinction, and a basement were all added. Radio carried the Mormon General Conference for the first time in October 1924, and the Tabernacle was retrofitted as a radio then television studio, though broadcasting had always been its business. Physicist and devout church member Harvey Fletcher was later a consultant on microphone placement when the building became a recording studio for the Choir (Hicks Citation2015, 86). 1949 saw the first television broadcast, and 1962 shortwave transmission to members outside the United States. Colour TV came in 1967, cable in 1975, and satellite transmission in 1980. In 1990, “time-variant electro-acoustic enhancement systems” were installed for the Choir. The building underwent a massive remodelling at the turn of the millennium, including seismic upgrades and reinforcements and a controversial replacement of the uncomfortable pioneer-era benches, which reduced seating capacity but spared many a latter-day backside. The new massive conference centre opened by the Church in 2000 assumed the central role for word and music, leaving the Tabernacle to take on that aura reserved for old things.

Indoor and outdoor voices

The Tabernacle was designed first and foremost as a meeting place for members of the church to assemble and hear sermons free from the buffetings of wind and weather. Its job was to spare listeners the rigours of the elements and speakers the taxing of their lungs. Without a physical shelter, the aural discipline of the listeners was vital, and is a recurring theme in nineteenth-century Mormon oratory. Apostle George A. Smith, Joseph Smith’s cousin, said that speaking in the Bowery, a shade pavilion that preceded the Tabernacle on Temple Square, was “enough to try the nerves of the strongest man and the lungs of a giant.” Apostle Parley P. Pratt called for “great order and strict attention” among listeners in 1855. Heber C. Kimball of the First Presidency in 1863 prayed for a miracle like the moment when Jesus calmed the storm on the Sea of Galilee: “My prayer is that the winds may cease for a little while, that I may be able to speak so that you can all hear.” The voice was not the only the thing the elements assailed: George A. Smith joked in a 1855 talk that the wind threatened to blow his hairpiece away (all quoted in Peterson Citation2002, 10–11). At the last general conference before the Tabernacle was finished, Smith noted that “‘Mormonism’ has seemed to flourish best out of doors.” But, he continued, the Tabernacle would open a new era and prevent the famine of “hearing the word of the Lord” prophesied in Amos 8:11 (quoted in Grow Citation1958, 43). It was a building designed to house God’s voice, to filter and concentrate, to gather and disperse it, as uttered by his mouthpieces (human servants). It was a stage for working out the meaning of hearing, both physical hearing and the hearing that goes beyond audible sound into zones of silence or spirit.

Building the hardware didn’t put a stop to softer forms of discipline. Once the Tabernacle was open, pleas for auditory decorum continued. In an April 1898 sermon, for instance, President Joseph F. Smith noted the unanticipated consequences of a building so democratically attuned to sound propagation: “It is the wonderful acoustic properties of this house that actually makes it so difficult, in one respect, to make the people hear when there are so many together as are here today, because every little sound tends to confuse the voice of the speaker” (quoted in Peterson Citation2002, 17). There were regular efforts from the pulpit to get congregants to stop whispering and shuffling their feet. A particular problem came from the penchant for bringing children along, a practice fostered both by pro-natalist doctrine and family-oriented worship culture. Speaking in the new Tabernacle, Brigham Young called noisy children “a source of considerable annoyance” (he himself had fifty-four). A silent “cry” room was added in 1951 (where I sat in 1960 as a restless two-year-old when my uncle took me to hear the Tabernacle Choir). Even indoors, the struggle for the voice’s audibility continued. The drama of hearing the voice through the noise is almost structural in Mormon worship; attend any Sunday meeting still and you can expect waves of acoustic caterwauling from small children. The Salt Lake Tabernacle building stages that drama.

Sounds spoken on the house tops and whispered

The Tabernacle was the centre point from which the sound went forth to all the world. The global address of the sermons delivered there was partly a rhetorical matter, with the well-worn formula that the Gospel must go to all “nations, kindreds, tongues, and peoples,” even if no larger group heard than those present. But systems of global dispersion were in place to spread Tabernacle-born words abroad, both by print media (the Journal of Discourses being the key organ) and by human emissaries carrying doctrine by word of mouth (missionaries). From that centre point, spokes of implied influence radiated. A look at the Journal of Discourses shows that things could sometimes get uncorked in the Salt Lake Valley – there are plenty of exotic notions in circulation there that theological critics of Mormonism today can amply harvest, sometimes to embarrassing effect, thanks to the Journal’s digital remediation.

But not all the preaching was lofty or edgy. One late nineteenth-century visitor to the Tabernacle noted that sermons could range across topics including “the best manure for cabbages, the perseverance of the Saints, the wickedness of skimming milk before its sale, on bedbug poison, teething in children, worms in dried peaches, and any possible thing which can be imagined” (quoted in Walker Citation2005, 233). The mix of dried peaches and perseverance, the mundane and the sublime, remains a hallmark of Mormon oratory. In the same way, the sounds of the Tabernacle range from the grounded to the ethereal, from the collective voice of the choir or of church leaders to the pin-drop test, hovering on the edge of silence, that has been performed to visitors since the late nineteenth century.

The pin-drop and newspaper-tearing tests still proudly demonstrated to tourists fully work only at the foci of the building. The average period of reverberation was measured in 1928 as 4.76 seconds when empty and about one second when fully occupied, and this holds across almost all positions in the building. It is a classic “whispering gallery,” in which some distant sounds can be heard better than close ones. An auditor in the rear of the building can hear an unamplified speaker better than one in the middle zone, which is subject to interference and echoes (Hales Citation1930). A two-decades member of the Tabernacle Choir reported: “I remember (more than once) sitting in the baritone section during a break, and CLEARLY hearing a couple of sopranos way over on the other side of the loft, carrying on a conversation. But two tenors chatting only 10 feet away from me were inaudible.” He also reports that choral music sounds better in the space than instrumental due to its relative slowness of attack, and that engineers face challenges in recording music that combines both.Footnote2 The building has both live and dead spots (Esplin Citation2007, 39).

The oft-circulated idea that the Tabernacle is somehow acoustically without blemish is therefore hardly true, but the narrative of a sacred space designed with perfect acoustics has played a crucial cultural role in Mormonism.Footnote3 Perhaps its imposing presence has something to do with the remarkable number of Mormon-heritage acousticians, such as Carl Eyring, Vern Knudsen, S. S. Stevens, and Harvey Fletcher, Fletcher being one the most important acousticians of the twentieth century (Beardsley Citation2017). We can also think of Mormon-raised avant-garde composer La Monte Young and many more sound innovators, such as a remarkable bevy of lapsed-Mormon just-intonation enthusiasts and microtonalists (Grimshaw Citation2011, 155–62). The religion has a thing for sound, and sound served as an essential vector of its settlement of the Great Basin (Lindquist Citation2015).

The tabernacle as skēnē and prophetic mouthpiece

The completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869 (the Golden Spike marking the project’s conclusion was driven just a few dozen miles northwest of Salt Lake City) opened up new streams of tourists to the Mormon capital, many of them motivated by prurient or at least exoticizing interests in polygamy (Hafen Citation1997).Footnote4 The Tabernacle was a regular stop on the tourist itinerary, and its acoustics were a prime attraction: an 1880s Swedish visitor (Waldenström Citation1890, 515–16) described the pin-drop test exactly as it still happens. The influx of curious eyes and ears stirred debates among church leaders about the building’s sanctity. Was it more of a temple – off-limits to anyone but members in good standing – or a place for outreach and goodwill-building? The latter view won out and the Tabernacle became a stage for displays of Mormon gentility and refinement, a civic centre for speeches from distinguished guests, an auditorium for performances by visiting musical artists from John Philip Souza to Leonard Bernstein. (Bernstein’s visit had some rocky moments; members of the Choir were apparently shocked by his profane language. The Tabernacle is not equally hospitable to all sounds.) For several decades it was home to the Utah Symphony Orchestra (Barton Citation2007; Taylor Citation2007). Every U.S. president from Theodore Roosevelt to Richard Nixon spoke there except Calvin Coolidge, and so have a great many presidential candidates. Funerals for church presidents were also held in the Tabernacle, starting with Brigham Young. The building had a wide range of uses, and was a skēnē in the full classical sense, a stage for showing and sounding.

The Tabernacle’s architectural and aesthetic reception by outsiders has been mixed, starting from critics in the nineteenth century. One unsparing Canadian dignitary called it “a tumour of bricks and mortar arising from the face of the earth.” Another visitor said it had “no more architectural character … than … a prairie dog’s hole.” It was compared to a turtle, an egg, “a pumpkin half buried in the sand” (Robison and Randall Dixon Citation2014, 259), the cover of a serving dish, an inverted soup tureen, a ship’s inverted hull, a watermelon, a mushroom, and an umbrella (Walker Citation2005, 209–12). Nevertheless, it eventually gained classic status among American religious buildings, being called by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1954 “one of the architectural masterpieces of the country and perhaps the world,” a judgement Mormons are fond of citing (quoted in Grow Citation2005, 171). In 1971, it was designated a National Engineering Landmark by the American Society of Civil Engineers.

Within the tradition, in contrast, the building can have a mythic resonance. One apocryphal story has Young slicing a boiled egg in half to show the first architect his envisioned shape of the building (though Patte would remind us that an egg is oval, not elliptical). Equally apocryphal is the story that Young got the idea for its shape from “the best sounding board in the world, the roof of my mouth” (Grow Citation1958, 94). Whatever its accuracy, this slide from palate to palace does express the long-enduring understanding of the building as the enlargement of and sounding board for the prophetic vocal tract, itself the “mouthpiece” for God (for example, Jer. 15:19). Here the “tabernacle” takes on a key corporeal sense in line with the curiously prosthetic sense of “mouthpiece.” The biblical tabernacle or mishkan was “the tent of the presence” (Blondheim Citation2012), and its Mormon offspring serves as the amplifier of the voice of those who speak for God. The Salt Lake Tabernacle is an exemplary stage for what Jake Johnson (Citation2019) calls Mormonism’s “theology of voice,” in which both God and prophets actively engage in legitimate vocal theatricality.

The voice is already, of course, a metaphysically mysterious entity both material and evanescent. Voices are both muscular and atmospheric, full of both signs and air (Cavarero Citation2005; Dolar Citation2006; Kittler, Macho, and Weigel Citation2001). Voices are in bodies, but they are also out of bodies: “What I say goes,” as Steven Connor (Citation2000, 3) puns. The Tabernacle only amplifies these fruitful tensions, as a vocal cavity made of wood, plaster, stone, rawhide, and animal hair or as a musical instrument – some liken the building’s all-wood acoustic shell to a resonator, like the body of a cello. It was to be a speaking machine for oracles, a kind of building-sized voice trumpet, a broadcast relay before the fact. It is a premier example of a sonic object that resounds over time and with many sorts of sound.

The temple and the tabernacle

One wag called the Tabernacle “a giant tortoise that has lost its way,” and one almost senses that it might one day pack up and start slowly moving on. But the Tabernacle is not alone on Temple Square, and the Salt Lake Temple next door gives no such impression. The Tabernacle stages events, but the Temple binds time and eternity through religious rituals of baptism and marriage. The Temple is the religiously indispensable building of the two. It is cut out of the surrounding mountains and is meant to be a kind of mountain itself. It took a biblically resonant forty years to build (1853–1893) and is not going anywhere, with its nine-foot thick granite walls at the base. Young said he designed it to last a thousand years.

But no sound comes from its midst. Unlike the Tabernacle, the Temple is not open to tourists, visitors, or even all members of the church. No acoustical care is known to have been put into its architecture. The only sound associated with the Temple is the legend that the angel Moroni statue atop its tallest spire will sound his trumpet at the second coming of Christ. Though with no basis in doctrine, this bit of folklore suggests that the Temple would only produce sound in apocalyptic conditions. The Tabernacle, in contrast, is almost a living monument to the Mormon trek through the American wilderness to Utah, and its most famous song, the pioneer anthem of endurance “Come, Come Ye Saints,” pulls listeners continually back to nineteenth-century days of exile and persecution. The building is saturated with the chronic sound of this song.

At the centre point of a hierocentric urban plan, and due west of the Temple on the city’s east–west axis, the Tabernacle is the historic heart of the Mormon soundscape, the public sounding counterpart to the sacrosanct silent temple a few paces to the east. The Temple is the set-apart house of God; the Tabernacle the public place where the voice of the prophets could be heard. The Temple is scripted with ritual exactitude; the Tabernacle has ever-varying programmes. We might supplement Heidegger’s Götterschau with a new term: Prophetenklang, the sound of the prophets. Not simply the binding point of heaven and earth or axis mundi, the temple was also the point from which power emanated to the surrounding territory, a space-binding and time-binding medium for both earth and heaven. As its consort and satellite, the Tabernacle shares in some of that power. What the Temple did in silent granite and by spiritual immensity, the Tabernacle did in sounding assembly, and later, via radio, TV, satellite, and internet. Both emanated and gathered presence and power, but in different ways. The Temple did so by sacred charisma and a claim on eternity (time); the Tabernacle by music and the spoken word carried by voice, print, and radio and television waves (space).

Auditory pilgrimage

As noted, after day one in 1830 it was never possible to gather the membership under one roof due to sheer numbers, persecution, and dispersion. Brigham Young (Citation1861) once said that given a thousand years of unmolested work the Saints could “build a room that will contain as many people as can hear the speaker’s voice.” He never dreamt of electrically enhanced vocal projection. Once amplification and broadcasting arrived, church leaders fit them inexorably into their narrative, like a long line of American religionists awed by “the rhetoric of the electrical sublime” (Carey Citation1989, 206ff). They figured radio as a kind of substitute assembly, presence at a distance, auditory pilgrimage (Feller Citation2015). As Dayan and Katz (Citation1992) have shown, broadcasting can take on a sacral colouring thanks to its ability to transport listeners and viewers and to evoke imagined communities and assemblies.

The April church-wide General Conference of 1923 used amplification for the first time, finally more or less solving the long-standing problems of hearing in the building: microphones and loudspeakers simply overpowered the echoes in the mid-section (Robison and Randall Dixon Citation2014, 161). The apostle and scientist John A. Widtsoe incorporated the new sound apparatus into his sermon at the Conference. He saw the microphone as both a technical advance and a moral lesson, as sound waves from the air were transformed and then “thrown into some other medium, and carried on again into the air until the voice is spread broadcast over the earth, if we so desire.” We should aim, he exhorted, to become amplifiers that receive “the whisperings of the Holy Spirit” and “make ourselves clear instruments for the discovery of the great truth that God has in store for all of us” (Widtsoe Citation1923, 48). Because matter and spirit are ultimately one in Mormon metaphysics, every new technical medium is ripe for spiritual allegory (Peters Citation2015b, 414–18). Especially interesting is Widtsoe’s treatment of transduction as a religious process. Discerning the whisper of the spirit so as to receive and amplify it described the work of both sound technologies and disciples. Widtsoe, like many others in the Latter-day Saint tradition, was invoking the biblical notion of a kind of hearing that went beyond the flesh of the ears catching vibrations.

The Tabernacle stages the religious exercise of hearing, building on an ancient tradition of treating hearing as something that goes beyond the physics and psychology of audition. Of the many sounds that have come from the building – the hoarse shouts of pioneer oratory, the reverberant echoes of feet sliding and children wailing, the swelling sounds of the organ, the lush blends of the Tabernacle Choir or Utah Symphony – perhaps its most famous sound remains the pin drop, a sound that almost magically appears with clarity out of the midst of distance. Its logic is that of a whisper (Li Citation2011) and of an epiphany. The Tabernacle accentuates sound’s existence in disappearing and disappearance in existing. At its rededication after major updates in 2007, several sermons played on the theme of a sound that transcends physical vibration (Faust Citation2007; Hinckley Citation2007; Packer Citation2007). They invoked a sound that both went back to the nineteenth century and came from beyond.

Perhaps the best example of the Tabernacle as staging long-lasting sounds beyond sounds comes in a memory from the late Latter-day Saint poet Emma Lou Thayne (1924–2014) of Helen Keller’s visit to the Tabernacle in 1941. Aided by her companion Anne Sullivan, Keller gave a talk and then asked to “hear” the organ. The President of the Church led her to touch the console as virtuoso Alexander Schreiner played variations on – what else? – “Come, Come Ye Saints.” Keller wept and was visibly moved. The recollection of Thayne’s teenaged witness of Keller’s sensory transduction inspires a kind of rapture in her memoir: “So then – that tabernacle, that singing, my ancestors welling in me, my father beside me, that magnificent woman, all combined with the organ and the man who played it and the man who had led her to it – whatever passed between the organ and her passed on to me” (Thayne and Warner Citation2011, 45–46). Commenting on this passage, Harris and McMurray note Keller’s “noncochlear auditions” (Citation2017, 44). This wonderful term might be generalised beyond the immediate context of Helen Keller. The category of noncochlear audition, of nonnormative hearing that is not only acoustic or perceptual, might stand in for Mormon ways of (thinking about) hearing in general.Footnote5

Hearing the voice of god

The study of the Salt Lake Tabernacle teaches us several things: that buildings can be media and that media houses are particularly interesting kinds of buildings, that religious imagination can give metaphorical life to edifices, and that sound production and recording are indexes of communal relationships and grounds for metaphysical speculation. It also suggests something more elusive. Buildings for the voice of God are curious because that voice is very curious.

As Hollywood has given it to us, the voice of God is often a campy joke that embodies “the bald aspiration of the basso profundo – pompous, overbearing – the term ‘the voice of God’ carries with it an element of ridicule” (Wolfe Citation1997, 151) (think of Charlton Heston or Orson Welles). Contrary to Hollywood, the biblical voice of God is rarely booming and omnidirectional: it has to squeak through a multitude of filters. In the Gospel of John (12:28–30) the Father’s voice is confusedly heard as thunder or an angel’s overheard speech, as if echoing the thunderings and the sound of the shofar atop Sinai (Exodus 19; Deut. 4–5). Jeremiah says that God’s voice utters like the weather, when the clouds are full of rain, with mists, rain, thunder, and wind (Jer. 51:16). Elijah, after his spectacular fireworks against the priests of Baal, discovered that God was not in fire or earthquake but rather in what the King James Version translates as “the still small voice” and others translate as “the sound of sheer silence,” “a voice of thin silence,” or the “sound of a light whisper” (1 Kings 19:12; MacCulloch Citation2013, 18). In a similar way, the voice of God “hisses forth” in the Book of Mormon and when it speaks to a human assembly on earth that does not even recognise it as a voice at first – God’s voice is first felt, piercingly, and only understood somatically and semantically as a voice on the third iteration, when the multitude “did open their ears to hear it” (3 Nephi 11:3–7).

The psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, considering this very topic, discusses how the shofar, the ceremonial Jewish ram’s horn sounded at anniversaries and in states of emergency, calls on Israel and on God to remember, and combines the moaning sound of the slaughtered calf with the bellowing of God’s breath. The voice of God seems never to sound without some kind of muffling (Lacan Citation2004, ch., 18). It is the prophetic voice that rings out, perhaps in the wilderness. But the voice of God hardly ever sounds with perfect clarity to human ears. Theophany and theophony are always matters of mediation, of things getting in the middle. In the case of the Salt Lake Tabernacle, acoustics is at once the drama of the tuning of the heart, of spiritual readiness, of listening discernment of divine things, of sorting sound from noise, and also a material field for the exercise of economic, political, religious, communal, and architectural discipline, whose ultimate dominion is time as well as space. This building suggests that theophony often hovers on the edge of silence, rather like a pin drop, and reminds us of Lacan’s point that the voice of Yahweh is made of wind and a slaughtered calf – rather like the Tabernacle itself.

Acknowledgments

In the many years I have worked on this paper I have accumulated many debts. I thank Amanda Beardsley, Menahem Blondheim, Mario Carpo, Joseph Clarke, Samantha Cooper, Mary Depew, Thomas L. Durham, Terryl Givens, Nathan Grow, Morgan Jones, Benjamin Lindquist, Peter McMurray, Leendert van der Miesen, Mara Mills, Benjamin Peters, Alexander Rehding, Kate Sturge, Emily Thompson, and Viktoria Tkaczyk for comments and suggestions. Conversations with Judd Case were formative.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

John Durham Peters

John Durham Peters is María Rosa Menocal Professor of English and Professor of Film and Media Studies at Yale University. He is the author of the following books, all published by the University of Chicago Press: Speaking into the Air: A History of the Idea of Communication (1999), Courting the Abyss: Free Speech and Liberal Tradition (2005), The Marvelous Clouds: Toward a Philosophy of Elemental Media (2015), and Promiscuous Knowledge: Information, Image, and Other Truth Games in History, co-authored with the late Kenneth Cmiel (2020). He has also published diverse articles in sound studies.

Notes

1. Due to limitations of space, this paper hardly touches the history of the Tabernacle Choir, but see Hicks (Citation2015) for the definitive study.

2. Personal communication, Thomas L. Durham, 14 September 2012.

3. A good example is a recent entry on the Tabernacle’s official blog on the pin-drop test: https://www.thetabernaclechoir.org/articles/acoustics-of-the-salt-lake-tabernacle.html?lang=eng.

4. Two of the most famous literary visitors, Samuel Clemens and Sir Richard Burton, arrived before the rail connection was completed.

5. For a different approach to hearing beyond sound, see Eidsheim (Citation2015).

References

- Barbieri, P. 1998. “The Acoustics of Italian Opera Houses and Auditoriums (Ca. 1450–1900). Trans. Hugh Ward-Perkins.” Recercare. 10:263–328.

- Barton, G. E. 2007. “Sacred Events of the Great Tabernacle: A Multi-faceted Edifice.” Pioneer. 54(2):12–15.

- Beardsley, A. 2017. “God in Stereo: The Salt Lake Tabernacle and Harvey Fletcher’s Telephonic Symphony.” Paper Delivered at the “Knowing Mormonism Through Sound” Session, Mormon Scholars in the Humanities Conference, May 26 2017, Boston University.

- Blesser, B., and L.-R. Salter. 2007. Spaces Speak, Are You Listening? Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Blondheim, M. 2012. “Prayer 1.0: The Biblical Tabernacle and the Problem of Communicating with Deity.” Paper Presented at the 62nd Annual Meeting of the International Communication Association, Phoenix, Arizona.

- The Book of Mormon. 1830. https://www.lds.org/scriptures/bofm?lang=eng

- Carey, J. W. 1989. “Technology and Ideology: The Case of the Telegraph.” In Communication as Culture. Boston: Unwin Hyman; p. 201–230.

- Cavarero, A. 2005. For More than One Voice: Toward a Philosophy of Vocal Expression. Translated by Paul A. Kottman. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Clarke, J. L. 2015. “Catacoustic Enchantment: The Romantic Conception of Reverberation.” Grey Room. 60(Summer):36–65. doi:10.1162/GREY_a_00175.

- Connor, S. 2000. Dumbstruck: A Cultural History of Ventriloquism. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Dayan, D., and E. Katz. 1992. Media Events: The Live Broadcasting of History. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Doctrine and Covenants of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Containing Revelations Given to Joseph Smith, the Prophet with Some Additions by His Successors in the Presidency of the Church. https://www.lds.org/scriptures/dc-testament?lang=eng

- Dolar, M. 2006. A Voice and Nothing More. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Eidsheim, N. S. 2015. Sending Sound: Singing & Listening as Vibrational Practice. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Ericson, S., and K. Riegert, eds. 2010. Media Houses: Architecture, Media, and the Production of Centrality. New York: Peter Lang.

- Esplin, S. C. 2007. The Tabernacle: An Old and Wonderful Friend. Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press.

- Eyring, H. B. 2016. “Where Two or Three are Gathered.” Ensign. 46(5):19–22.

- Faust, J. E. 2007. “Salt Lake Tabernacle Rededication.” https://www.lds.org/general- conference/2007/04/salt-lake-tabernacle-rededication?lang=eng

- Feller, G. 2015. “Sacralizing Signals for the Institution and the Individual: KZN and the LDS Church’s Discursive Approach to Radio as a New Medium.” Culture and Religion. 16(3):327–343. doi:10.1080/14755610.2015.1083456.

- Grimshaw, J. 2011. Draw a Straight Line and Follow It: The Music and Mysticism of La Monte Young. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Grow, N. D. 2005. “One Masterpiece, Four Masters: Reconsidering the Authorship of the Salt Lake Tabernacle.” Journal of Mormon History. 31(2):171–197.

- Grow, S. 1958. A Tabernacle in the Desert. Salt Lake City: Deseret Book.

- Hafen, T. K. 1997. “City of Saints, City of Sinners: The Development of Salt Lake City as a Tourist Attraction, 1869–1890.” Western Historical Quarterly. 28(3):342–377. doi:10.2307/971025.

- Hales, W. B. 1930. “Acoustics of the Salt Lake Tabernacle.” Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1(2A):280–292. doi:10.1121/1.1915181.

- Hamilton, C. M. 1983. The Salt Lake Temple: A Monument to A People. Salt Lake City: University Services.

- Harris, S. J., and P. McMurray. 2017. “Sounding Mormonism.” Mormon Studies Review. 5:33–45. doi:10.18809/msr.2018.0104.

- Hicks, M. 2015. The Mormon Tabernacle Choir: A Biography. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- Hinckley, G. B. 2007. “A Tabernacle in the Wilderness.” https://www.lds.org/general-conference/2007/04/a-tabernacle-in-the-wilderness?lang=eng

- Howlett, D. J. 2014. Kirtland Temple: The Biography of a Shared Mormon Sacred Space. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- Johnson, J. 2019. Mormons, Musical Theater, and Belonging in America. Urbana: University of Illinois.

- Kircher, A. 1673. Phonurgia Nova, sive de mirabilibus prodigiis soni, vocisque per machinas omnis generis propagandi. Kempten: Rudolph Dreherr.

- Kircher, A. 1673. Phonurgia Nova, sive de mirabilibus prodigiis soni, vocisque per machinas omnis generis propagandi. Kempten: Rudolph Dreherr.

- Kittler, F. 2009. Musik und Mathematik 1: Hellas 2; Eros. Munich: Fink.

- Kittler, F., T. Macho, and S. Weigel, eds. 2001. Zwischen Rauschen und Offenbarung: Zur Kultur- und Mediengeschichte der Stimme. Berlin: Akademie Verlag.

- Lacan, J. 2004. L’angoisse. Paris: Seuil.

- Li, X. 2011. “Whispering: The Murmur of Power in a Low-fi World.” Media, Culture & Society. 33(3):19–34. doi:10.1177/0163443710385498.

- Lindquist, B. 2015. “Testimony of the Senses: Latter-day Saints and the Civilized Soundscape.” Western Historical Quarterly. 46(1):53–74.

- MacCulloch, D. 2013. Silence: A Christian History. New York: Viking.

- McMurray, P. 2015. “A Voice Crying from the Dust: The Book of Mormon as Sound.” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought. 48(4):3–44.

- Meyer, B. 2011. “Mediation and Immediacy: Sensational Forms, Semiotic Ideologies and the Question of the Medium.” Social Anthropology. 19(1):23–39. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8676.2010.00137.x.

- Packer, B. K. 2007. “The Spirit of the Tabernacle.” https://www.lds.org/general-conference/2007/04/the-spirit-of-the-tabernacle?lang=eng

- Park, B. E. 2010. “Salvation through a Tabernacle: Joseph Smith, Parley P. Pratt, and Early Mormon Theologies of Embodiment.” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought. 43(2):1–44.

- Patel, R., and A. Bassuet. 2012. Acoustics, Architecture, and Music: Understanding the Past and Present, Shaping the Future. Symposium on the Sound of Architecture. New Haven: Yale University.

- Patte, P. 1782. Essai sur l’architecture théatrale, ou, De l’ordonnance la plus avantageuse à une Salle de Spectacles, relativement aux Principles de l’Optique & de l’Acoustique. Paris: Moutard.

- Peters, J. D. 2015a. The Marvelous Clouds: Toward a Philosophy of Elemental Media. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Peters, J. D. 2015b. “Media and Mormonism.” In T. L. Givens and P. L. Barlow, edited by. The Oxford Handbook of Mormonism. New York: Oxford University Press; p. 407–421.

- Peterson, P. H. 2002. “Accommodating the Saints at General Conference.” BYU Studies. 41(2):4–39.

- Roberts, A. D. 1975. “Religious Architecture of the LDS Church: Influences and Changes since 1847.” Utah Historical Quarterly. 43(3):307–327.

- Roberts, B. H., ed. 1974. History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Vol. 5. Salt Lake City: Deseret Book.

- Robison, E. C., and W. Randall Dixon. 2014. Gathering as One: The History of the Mormon Tabernacle in Salt Lake City. Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press.

- Schmidt, L. E. 2000. Hearing Things: Religion, Illusion, and the American Enlightenment. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Shell, M. 2006. “Moses‘ Tongue.” Common Knowledge. 12(1):150–176. doi:10.1215/0961754X-12-1-150.

- Smith, J. 1838. “History.” https://www.lds.org/scriptures/pgp/js-h/1.17

- Taylor, T. 2007. “A Community Gathering Place.” Pioneer. 54(2):16, 18–22.

- Thayne, E., and L. Warner. 2011. The Place of Knowing: A Spiritual Biography. Bloomington, IN: iUNiverse.

- Vitruvius. 1999. Ten Books on Architecture. (De architectura libri decem), translated by Ingrid D. Rowland. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Waldenström, P. 1890. Genom Norra Amerikas Förenter Stater: Reseskildringar. Stockholm: Pietistens Expedition.

- Walker, R. W. 2005. “The Salt Lake Tabernacle in the Nineteenth Century: A Glimpse of Early Mormonism.” Journal of Mormon History. 31(2):198–240.

- Watson, E. J. 1979. “The Nauvoo Tabernacle.” BYU Studies. 19:416–421.

- Widtsoe, J. A. 1923. Ninety-Third Annual Conference of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Salt Lake City: Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

- Wolfe, C. 1997. “Historicizing the ‘Voice of God’: The Place of Vocal Narration in Classical Documentary.” Film History. 9(2):149–167.

- Young, B. 1861. “True Testimony, Etc.” Journal of Discourses. 9:1–6. http://jod.mrm.org/9/1