ABSTRACT

How and why did African households under colonial rule make the decision to educate their children or not, and how did this micro-level decision making affect the diffusion of education in colonial Ghana? This paper addresses these questions and shows that many households were reluctant to enrol their children in school because the costs of colonial education were prohibitive, and the benefits were limited. Unemployment of school leavers was a major social problem throughout the colonial era and returns to education did not justify investments in education. The demand for education was relatively high in areas where the demand for skilled labour was high, and from the late 1930s when there were growing pay-offs to colonial education. Overall, the paper points to the need to examine interactions between supply and demand factors in order to understand variations in human capital accumulation in sub-Saharan Africa.

Introduction

It is generally agreed that equal access to education enhances social mobility and promotes economic development in the long run (Coleman Citation1965; Glaeser et al. Citation2004; Goldin and Katz Citation2008). However, despite efforts to expand access to educational facilities in sub-Saharan Africa, the region has the highest rates of educational exclusion in the world today. More than one out of five children between the ages of 6 and 11, one-third of 12- to 14-year-olds, and nearly 60% of young people aged 15 to 17 are not in school (UNESCO Citation2019). Further, gender parity in education is still far from achieved. Several scholars claim that this inequality of education has its roots in the colonial era, when formal schooling in Africa spread unevenly along geographical, gender, and ethnic lines (Bolt and Bezemer Citation2009; Feldmann Citation2016; De Haas and Frankema Citation2018).

Commonly invoked explanations for the uneven diffusion of Western education in colonial Africa focus on supply factors as they highlight the nature of missionary expansion and differences in metropolitan educational policies and practices (Subramaniam Citation1979; Benavot and Riddle Citation1988; Grier Citation1999; Brown Citation2000; Dupraz Citation2019). While missionary activities and colonial government policies were important and deserve to be extensively studied, an equally important determinant of educational expansion was the responses of the indigenous population (Huillery Citation2009; Gallego and Woodberry Citation2010; Cogneau and Moradi Citation2014; Jedwab, Meier zu Selhausen, and Moradi Citation2018). Although recent scholarship has acknowledged the role of African demand, much remains unknown about specific contextual variables that influenced the micro-level decision to enrol children in school, or not (Frankema Citation2012; De Haas and Frankema Citation2018).

This paper contributes to the strand of literature emphasizing colonial legacies in current inequality of education in Africa. The paper focuses on Ghana and covers the period from the 1890s to independence in 1957. Despite a long history of European influence and being a relatively rich colony, the spread of Western education was sluggish and uneven. Gross enrolment ratio in primary education was low and only began to rise after the 1930s. In 1938, Ghana’s gross primary school enrolment rate was 8, compared to 12 for Kenya, 16 for Botswana, 27 for Uganda, 30 for Zambia, 33 for Zimbabwe, 35 for Malawi, and 38 for Mauritius (Frankema Citation2012). By 1948, only 4% of Ghana’s population of over four million had six years of education or more (Foster Citation1965, 118).Footnote1 Further, throughout the colonial era, northern Ghana trailed behind the south in terms of number of schools, total enrolment, and educational attainment of its population (Foster Citation1965; Thomas Citation1974; George Citation1976). There were also significant gender gaps in enrolment rates throughout the colonial era and in 1950, 35% of boys but only 12% of girls were enrolled in primary school (Akyeampong and Fofack Citation2014; Lee and Lee Citation2016). Both regional differences and gender gaps in access to education have persisted until today.

The paper makes three contributions to the existing literature on the spread of education in colonial Africa. First, it shows that to reach a comprehensive understanding of the reasons for uneven development of education, empirical analyses should focus more on the interactions between colonial policies and African responses than they have done so far. Second, it outlines the specific social and economic determinants of indigenous agency and its effects on educational development. Finally, it concludes that where other social and economic factors are unequally distributed between social groups, supplying school facilities, while leaving other factors unattended to, is not enough to ensure equal educational opportunity.

The rest of the paper proceeds as follows. I first provide a brief summary of previous literature on the reasons for educational expansion in general and the origins and spread of formal education in sub-Saharan Africa and Ghana specifically. Second, I present an overview of educational development in colonial Ghana. Both supply and demand are highlighted and regional and gender disparities in education are discussed. Next, I examine how opportunity and monetary costs of education influenced demand. Subsequently, I outline the potential benefits of colonial education with an emphasis on occupational opportunities and financial rewards. The final section concludes.

Supply and demand in educational expansion

One can divide the literature on educational expansion into emphasizing either supply side or demand factors. Many scholars representing the ‘supply-side’ highlight the role of the state, policymakers, political or religious leaders, and other corporate actors (Archer Citation1979; Boli, Ramirez, and Meyer Citation1985; Lindert Citation2004; Gallego Citation2010). From this perspective, conflict and competition between different class and status groups affect the characteristics of educational expansion – for example, if it is inclusive or targeted. Further, the distribution of political power and the role of political elites and their perceptions of the likely benefits of an educated populace affect the size and direction of educational investments (Engerman and Sokoloff Citation2002; Lindert Citation2004). This literature does not account for the motivations of the recipients and assumes that acquiring more education is always beneficial for households and individuals.

Meanwhile, scholars representing the ‘demand-side’ argue that supply is highly elastic in the long run and determined by primary actors such as individuals or the family unit (Craig Citation1981). Education is then a consumption good demanded for the satisfaction it provides. It expands when preferences and costs remain constant and school enrolment rises with real income. Given that the benefits of education continue into the future or come later, education is also an investment. Families and individuals invest in education when the private benefit from doing so exceeds the private cost (Becker Citation1964; Clemens Citation2004).

However, demand-side explanations anchored on the cost–benefit analysis of families and individuals tend to be deterministic and assume that families make their decisions based on perfect information and foresight on the potential costs and benefits. Instead, decisions are made under uncertain conditions (Levhari and Weiss Citation1974; Cunningham Citation2000, 414; Lord Citation2011, 89). It is not possible for potential investors to predict the future demand for skills and the potential returns from investment in schooling nor how long they can expect to receive returns on educational investments. Differences in the demand for education and disparities in levels of enrolment are therefore partly due to differential access to and valuation of information about the effects of schooling (Psacharopoulos Citation1981).

Much of the extant literature on the uneven spread of education in colonial sub-Saharan Africa has focused on explaining supply-side factors (Frankema Citation2012, 338). It is argued that, especially in British-ruled colonies, the provision of education was virtually a monopoly of Christian missionaries. The spread of Western education therefore depended on the character of missionary expansion. Areas where missionaries decided to concentrate their efforts, typically in coastal territories and administrative towns which were more accessible, developed, healthier, and safer, took the lead in educational development (Craig Citation1981, 194). The uneven distribution of schools is explained by deliberate government policy. For example, in some Islamic or peripheral inland areas missionary activities were restricted in order to avoid conflicts (Bolt and Bezemer Citation2009, 32; Cogneau and Moradi Citation2014, 698).

Nevertheless, Frankema (Citation2012, 352) has shown that once supply-side constraints were eliminated, African demand became the key determinant of educational expansion in the last two decades of colonial rule. Demand was not uniform and depended on a range of cost–benefit calculations made by African families. It was high only in areas where the economic benefits were most conspicuous and where education offered opportunities for socio-economic mobility (Craig Citation1981, 193; Frankema Citation2012, 349). De Haas and Frankema (Citation2018) for example, argue that in Uganda, while new labour market opportunities were created under the colonial era, they were unevenly distributed, and this was reflected in the demand for education. This they find to be particularly relevant for explaining low female enrolment.

For colonial Ghana, Lord (Citation2011) argues that from the 1940s until independence in 1957 demand was low because colonial education was a costly and uncertain investment. Further, Foster (Citation1965, 125–128) has pointed out that the development of trade and the growth of cash crops led to the expansion of education. However, given that these economic developments impinged differentially upon various regions, the associated demand and subsequent provision of educational services was unequal. Others contest demand-side explanations and claim that regional inequality was due to the colonial government’s educational strategies that were biased against the north (Ladouceur Citation1979; Plange Citation1979; Abdulai and Hickey Citation2016).

While the above views on educational expansion might appear to be poles apart it is possible to unite them (Craig Citation1981). ‘State’ or ‘corporate’ action and primary (family or individual) action are both essential to educational development, but their relative importance vary depending on the case. The paper adheres to this approach of emphasizing the interaction between supply and demand, and how the characteristics of this interaction vary over time and space. Such focus has so far been missing in the literature on educational spread in colonial Africa and the reason for this omission is the limited understanding of the factors influencing African responses to colonial state and missionary efforts. It is the primary objective of this paper to provide such insights.

Educational development in colonial Ghana

European supply and African responses

European merchant companies constituted the first wave of colonial expansion into the territory that is current-day Ghana in the late sixteenth century, and they were the first to introduce Western education (McWilliam and Kwamena-Poh Citation1975, 17). Educational developments were sporadic, short-lived, and confined to coastal towns as they remained the subsidiary function of the trading companies (Kimble Citation1963, 61; Foster Citation1965, 44). British colonial authorities established publicly funded schools after 1821 and a new phase of educational expansion began in the third decade of the nineteenth century with the arrival of Basel missionaries in 1828 and the Wesleyans in 1835. Vigorous missionary activities resulted in the establishment of some mission schools that eventually absorbed the ‘government’ schools (Foster Citation1965, 49–50).

The early merchants and missionaries were met with indifference or even active opposition from the indigenous population. Even in the coastal towns, the bastions of merchant activities and colonial administration, the demand for education was very limited (Graham Citation1968, 191–192). Differently from trade, the local African societies did not deem the benefits of reading and writing, especially in a foreign language, as relevant (Kimble Citation1963, 61–62). After the first half of the nineteenth century, Africans who were influenced by the colonial administration and the European economy began to associate education with the prospects of employment as a teacher, clerk, or other higher administrative post, regular salary, increased authority and prestige, and a means of avoiding manual labour (Kimble Citation1963, 62). Educational expansion was not, however, without its challenges.

In 1852, the colonial government’s attempt to direct the educational system through the provision of schools turned out to be unsuccessful. An important contributing factor was the coastal population’s refusal to pay the poll tax that the government had wanted to use for the running of the schools (McWilliam and Kwamena-Poh Citation1975, 17). Even less progress was made in the interior and in 1876, a king of Asante reportedly indicated that:

We will not select children for education; for the Ashantee children have better work to do than to sit down all day idly to learn hoy! hoy! hoy! They have to fan their parents, and to do other work, which is much better.Footnote2

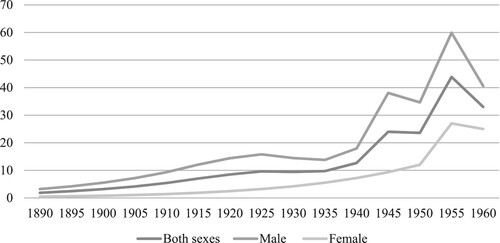

As can be seen in , educational development in the Gold Coast in terms of gross primary school enrolment ratios progressed slowly but steadily from the 1890s until the mid-1920s when it stagnated for roughly a decade. By the turn of the twentieth century, there were approximately 12,000 pupils enrolled in 129 assisted and 120 unassisted Christian mission schools, seven government schools, and two Mohammedan schools.Footnote4

Figure 1. Gross primary school enrolment ratio in Ghana, 1890–1960. Source: Lee and Lee (Citation2016).

Until the end of the nineteenth century, education was almost exclusively confined to the coastal area, but there were efforts to also supply other parts of the colony. In Ashanti, Christian missionaries were kept at bay until British occupation in 1896, but already by 1900 the Basel Mission, followed by the Wesleyans, had secured a substantial footing (Tordoff Citation1965, 195–201). Although they made progress, there were few inroads with Asantes and it was non-Asantes, primarily people from the coastal towns, who frequented their schools and churches (Allman and Tashjian Citation2000, 26). In 1908, it was estimated that the total Christian population in Ashanti was only ‘2,682 out of a population of half a million souls’ (Tordoff Citation1965, 201). Until the beginning of World War I, school attendance was low as many parents refused to send their children (Tordoff Citation1965, 201). As late as 1921, the total number of pupils enrolled was only 3,291 out of a child population (6–15 years) of 103,755.Footnote5 A decade later, there were 6,949 pupils in all 114 schools, representing about 3% of children in Ashanti (Cardinall Citation1931, 165).Footnote6 Meanwhile, in the Northern Territories, the colonial government was relatively active from the early twentieth century and pursued a special policy of free schooling, special courses, and other incentives to encourage parents to send their children to school.Footnote7 Still, the demand for education remained low.

However, significant overall educational expansion was to follow. As shows, gross primary school enrolment surged from above 9% in 1935 to 24% a decade later, and peaked at 44% in 1955. Cogneau and Moradi’s (Citation2014, 700) estimates show a similar trend with gross primary school enrolment ratio increasing from 10.5% in 1938 to 36.9% in 1955.Footnote8 We will return to the discussion of the relationship between wage increases and school enrolment. For now, I suggest that as investments in education take several years to pay off, it appears unlikely that more schooling could explain growth trends in the 1930s, but rather that improvements in income opportunities were behind growth in enrolment numbers.

Indigenous initiatives in the supply of education intensified with a rapidly growing demand after the 1930s. Hundreds of unassisted primary schools were established throughout the colony.Footnote9 Local communities started many of these schools without reference to recognized educational units or to the Education Department.Footnote10 Such schools were unregistered, ill-housed, lacked teaching and learning equipment, and with few exceptions, all were staffed with untrained indigenous teachers.Footnote11 Chiefs and native authorities also established and administered ‘national’ or ‘state’ schools receiving government assistance, while rich Africans began to establish private schools in urban areas (George Citation1976, 31).Footnote12 Further, like elsewhere in colonial Africa, African missionaries and teachers were the main agents of educational expansion in colonial Ghana (Foster Citation1965; Frankema Citation2012; Meier zu Selhausen Citation2019).

After the 1930s, the colonial government also opened primary schools in areas where missions had made little progress and established teacher training colleges, technical and vocational schools, and other institutions of higher learning.Footnote13 In 1951, when Ghana became self-governing, there were 3,198 schools, of which 1,378 were unassisted schools, 957 grant-aided schools by native authorities, 653 grant-aided schools, and 52 were government-funded schools.Footnote14 Therefore, educational advancement was due more to mission and private endeavour than to the efforts of the colonial state.

Regional and gender inequalities

The substantial increase in enrolment rates from the mid-1930s presented in and the successive growth in the number of schools discussed above, were primarily driven by the increase in educational development in the southern part of colonial Ghana. The regional bias is clearly reflected in and in , showing how education spread unevenly along geographical lines. In relative terms, measured as number of schools per 10,000 individuals, Togoland had more than 35 times as many schools as the Northern Territories, with the Gold Coast Colony and Ashanti in between.

Figure 2. Geographical location of schools in colonial Ghana, 1902, 1925, and 1938. Source: Cogneau and Moradi (Citation2014).

Table 1. Number of Schools per 10,000 population, 1910–1940.

In terms of share of pupils reached and literacy, there were clear differences between the north and the south. For example, only 0.22% of the child population in the north were receiving education in 1931, while in the Central and Eastern Provinces about 5% of the child population were in school.Footnote15 In 1948, 3.5% of the Gold Coast Colony’s population had attained six years of primary education. The number for the Northern Territories was 0.12%.Footnote16 As shows, in 1960, three years after Ghana’s independence, the regional inequalities in education were still noticeable. Close to 95% of the population aged six and above in the Northern Territories had never been to school and only 3.6% were attending school.

Table 2. School attendance (of persons aged six years and over) by region, 1960.

As discussed earlier, several studies have shown that government policies affected educational diffusion in colonial Africa (Bolt and Bezemer Citation2009; Cogneau and Moradi Citation2014). To explain differences in supply between the Gold Coast Colony, Ashanti, and the Northern Territories, we similarly scrutinize both the policies of the colonial state and the nature of missionary expansion. Above, we have described the role that trading companies, missionaries, and the government played for the spread of Western education in the coastal areas from the late sixteenth century onwards. Subsequently, the colonial state invited Basel and other mission societies to establish schools and begin evangelical work in Ashanti when it was occupied in 1896, and missionaries arrived in the north after it was formally declared a Protectorate in 1901.

However, unlike the rest of the territory, the colonial government subsequently restricted missionary activities in the north for many decades (Ladouceur Citation1979, 50–52, 58–60; Cogneau and Moradi Citation2014, 698).Footnote17 It was not willing to ‘make themselves responsible for the protection of the lives and property of missionaries, especially those of a foreign power’.Footnote18 Additionally, the colonial state’s isolationist ‘policy’ was supposedly meant to protect the north from disruptive outside influences on its local values and institutions (Ladouceur Citation1979, 57). Further, it was argued that unlike the south, where educational expansion was uncontrolled and quality was allegedly compromised, the colonial authorities could ensure that education in the north was of a higher quality (Ladouceur Citation1979). Plange (Citation1979) speculates that the real reason for the isolationist policies were to make the north a labour reserve for the cocoa growing south. In 1909 the colonial state itself established a school in the north, while it continued to discourage the establishment of missions. It was not until the 1930s that some missions began to operate in the north on a limited scale (Ladouceur Citation1979, 50). The restrictions of missionary activities had lasting consequences. For example, Abdulai and Hickey (Citation2016) claim that late educational development delayed the emergence of a northern educated elite that could influence the further distribution of public investments.

An equally important determining factor for the slow spread of education in the north was limited demand by the indigenous population (Foster Citation1965, 124; Hurd Citation1967, 219). Missionaries lamented the lack of desire for education among the people of the Northern Territories and in 1928, the governor of the Gold Coast Colony remarked that some schools in the north were closed and others were not filled.Footnote19 While there was a growing demand for education in the south from the mid-1930s, there was no similar trend in the north.Footnote20 As late as 1952, the Education Department noted parents’ reluctance to send their children to school in its annual report.Footnote21

Foster (Citation1965, 125–128) argues that there was limited demand for education in the north because of limited European contact and the absence of a strong export sector. Prior to the advent of western education, Ghana’s traditional social structures had inbuilt opportunities for mobility. Mobility depended on the exploitation of lines of descent and not mainly on the acquisition of wealth. Traditional societies of Ghana opposed colonial education and demand did not arise until the social system changed as a result of European contact. In the coastal areas for example, the establishment of British rule created an administrative structure which created new channels for mobility and for the acquisition of prestige and status outside the traditional modes. In other areas in the south, cocoa growing created increasing fluidity within traditional social structures and led to a greater demand for Western education (Foster Citation1965, 125). In the Eastern province, for example, there was increasing demand for education after the great cocoa boom of 1907 when large parcels of land were increasingly used for cultivating cocoa (Southon 1934, 123 cited by Foster Citation1965, 127). Although the Northern Territories had been attached to the Gold Coast since 1901, their traditional social organizations were less affected by European influences. The north was unsuitable for cocoa cultivation and being physically, culturally, and psychologically remote, the northern peoples ‘were in the Gold Coast, but they were not of it’ (Kimble Citation1963, 533).

In sum, limited missionary activities, the underdevelopment of the north, and limited demand for education as a result of limited European contact and the slow growth of an exchange economy account for the slow development of education in the north. We do not have the data to tease out the precise contribution of each of these factors to the regional bias in the spread of education in colonial Ghana, but this is not the aim of the present paper. Instead, the paper calls attention to the role the micro-level decision-making of parents and families – based on the assessment of the costs and benefits of western education – played in educational development in colonial Ghana.

Differences in demand also help to explain gender inequalities in education. shows that girls’ enrolment in schools lagged far behind that of boys throughout the colonial period. In 1890, gross primary school enrolment rate for boys was a little above 3% rising to 18% in 1940 and 60% in 1955. Girls’ enrolment rates in the same years were 0.46, 7, and 27% respectively.

Colonial authorities often bemoaned the fact that few girls were found in schools and that girls’ education lagged behind that of boys (Graham Citation1971, 71). In 1894, colonial officials contemplated instituting compulsory measures, albeit with potential social difficulties, to attract girls of the colony to school. ‘The sooner steps [were] taken to educate the girls of the colony’, they argued, ‘the better will the next generation of West Africans become’.Footnote22 In spite of this rhetoric, the Gold Coast government throughout the colonial era did not give special attention to girls’ education and missionary societies were the ones who promoted it (Graham Citation1971, 133; Baten et al. Citation2020).

Many parents were disinclined to enrol girls in school because as Collett, a Catholic missionary, remarked in 1928, ‘most of the parents seem to think it [western education] quite superfluous, if not harmful’ (Robertson Citation1984, 139). For missionaries, the ultimate goal for educating girls was for girls to acquire domestic skills to make them better wives and mothers (Graham Citation1971, 71). Therefore, there were differences in the kind of education boys and girls received. In some mission schools which concentrated on vocational/technical education, girls were taught sewing and how to cook (Robertson Citation1984, 139). Such domestic skills could however be acquired at home and for many parents, Western education was thought of primarily as the gateway to employment opportunities available only to boys (Graham Citation1971, 71).

Differences in enrolment between boys and girls were pervasive in all provinces of colonial Ghana. In 1930 for example, the Gold Coast Colony with a male child population of 305,439 and a female child population of 302,716 had 24,217 boys enrolled as compared to 7,780 girls. The Northern Territories, with a male and female child population of 155,852 and 134,474, had 574 boys and 61 girls respectively enrolled (Cardinall Citation1931, 199).Footnote23

In a survey of about 238 women in Accra in 1971–1972, Robertson found out that among the women who were in their 80s and 90s, only 5% had attended primary school, compared to 47% of those in their 40s and 30s (Robertson Citation1984, 141). Based on the generational differences, Robertson argues that it was not until after World War II that there was a drastic attitudinal change towards female education resulting in many girls attending school. Even so, as shows, the gap between male and female enrolment ratios persisted throughout the colonial era.

So far, we have mapped the spread of education and discussed the interaction between supply and demand. We now turn to a more in-depth analysis of the demand-side through the lens of African agency as we discuss the direct and indirect costs, expressed as opportunity and monetary costs, as well as benefits of education.

Costs of colonial education

In colonial Ghana, both indirect and direct costs of education were high (Lord Citation2011, Citation2015). First, the indirect costs of education were the often substantial opportunity costs in terms of the labour and income families lost by enrolling their children in school. Second, direct costs related to school fees, books, uniforms, and in later years various additional fees charged by mission schools for such items as sports, equipment, building, needlework, domestic science, or handwork (Busia Citation1950, 24). In this section, I discuss the relationship between changes in costs of colonial education and the trend in the spread of education (sharp increase in enrolment and number of schools after the mid-1930s) discussed in the earlier section on the development of education in colonial Ghana. Further, I consistently refer to the regional and gender differences depicted in and and .

Opportunity costs

The wealth and work that children embodied was assembled, circulated, and exchanged for the benefit of adults. As a result, the opportunity costs of education were high as it reduced the supply of labour available to parents and deprived them of other sources of capital and income (Lord Citation2011, Citation2015). The following discussion on opportunity costs is organized according to the different activities and economic sectors children were involved in during the colonial era: subsistence activities, pawning, mining, and cocoa production.

Until the early decades of the twentieth century, the basic work unit for subsistence and extra-subsistence economic activities for many indigenous Africans, was the conjugal family (Austin Citation1994; Allman and Tashjian Citation2000, 60–70). From an early age, boys accompanied their fathers to the farm helping them to carry tools and supplies, weed, plant, harvest, and transport crops, and assisted in craftwork (Kaye Citation1962, 194–199). Girls maintained homes, cooked, cleaned, took care of younger siblings, marketed farm produce, and gradually took on women’s food production roles in the fields (Robertson Citation1984, 70, 72–73, 165, 171–172). In coastal and riverine towns, children supported their parents in fishing and where mixed farming was practised, they tethered poultry and small livestock (Kaye Citation1962, 198). In pastoral communities in the Northern Territories, boys between the ages of 9 and 12 also herded cattle (Fortes Citation1938).

Whereas child labour enabled the economic flexibility and viability of households throughout the territory, nowhere was it more desperately required than in the Northern Territories. Forced labour recruitment by the colonial state and out-migration of labour from the northern savannah regions reduced the availability of labour for on-farm production. Colonial authorities often lamented that the drain of labour affected agriculture adversely.Footnote24 Children therefore took the place of absent men in crop cultivation and other subsistence-oriented activities. In 1922, a colonial official found a notable absence of young men at village meetings and received complaints from chiefs that they had to work the farms with old persons and children.Footnote25 Under these circumstances, parents in the north could hardly respond to calls to put their children in school.

Pawning of one’s children as a form of collateral was pervasive in many of the areas of pre-colonial and colonial Ghana and presented a lucrative alternative to sending children to school. Though some evidence on the gender composition of the pawns and slaves points to insignificant differences between the number and market value of male and female pawns in the pre-colonial nineteenth century, it appears females were more preferred, both for economic reasons and reproductive purposes (Austin Citation2005, 174–180, 234). In some communities, if a girl’s master seduced her into marriage, her family could waive off her bride wealth. This was a convenient way for some families to pay off their debts (Robertson Citation1984, 134). During the early colonial period, families betrothed girls sometimes even before they were born, to become pawn-brides of their creditors (Austin Citation2005, 146). Robertson states that for these reasons, ‘parents were not anxious to make their daughters, who had functional economic value, into luxury goods’ by enrolling them in schools (Robertson Citation1984, 139).

In the early years of the twentieth century, the extensive practice of pawning was cited as the ‘proper reason’ for the difficulties in getting ‘scholars from the people’.Footnote26 In the late 1950s, Polly Hill met elderly cocoa farmers who recalled from their childhood in the early twentieth century that they chose to be pawned to help their parents buy land for cocoa farming (Coe Citation2012, 297). Typically, when fathers pawned their own children, the children could also claim direct inheritance to their fathers’ farms (Coe Citation2012). Cases of child pawning appeared in the courts in the south at least up to 1942 (Austin Citation2005, 234). As late as 1948, some parents in famine prone areas in the north pawned their children in exchange for food in times of famine or sold their sons’ labour to pay local taxes (Van Hear Citation1982a, 505).

So far, we have discussed activities in the informal economy, but children were also employed in the wage sector. In mining towns, boys under the age of 14 worked as grass cutters, water boys, messengers, and apprentices, while girls were employed as carriers, diamond sorters, and cooks (Lord Citation2015, 246). Occasionally, the Public Works Department engaged children for tidying up roads and paths (Akurang-Parry Citation2002). Children were also employed by expatriate trading firms as porters and domestic servants by foreign contractors, missionaries, civil servants, and businessmen (Lord Citation2015, 249).

In the south, the expansion of cocoa production, the most spectacular development in the first four decades of colonial rule, had additional far-reaching implications on the demand for labour. It created new roles for children in planting, harvesting, processing, and transportation that were important regardless of expanded cocoa output and the increased use of hired labour (Austin Citation2005, 310). Kaye tells of an illiterate farmer with five wives and 27 children who would want more children because ‘there would be no need to engage labourers to weed [his] cocoa farm and to help in the plucking and in carrying the dried beans to the nearest weighing station if [he] had more children’ (Kaye Citation1962, 23).

At the same time, the expanding cocoa industry required additional labour for the cultivation and transportation of the crop. Many of the children working as carriers engaged in head loading cocoa were from the Northern Territories. By 1914, it was observed that

a large number of the children in this colony are engaged daily in heavy weight carrying. It is in fact their daily occupation … A great deal of this cocoa carriage is in the hands of the Wangaras [a tribe from the North] and it is not unusual to see immature children amongst them.Footnote27

In and , we noted a sharp increase in school enrolment and number of schools from the mid-1930s onwards. Further, we stated that the changing trend was primarily driven by an increasing interest in schooling in the south as Africans sought more lucrative and prestigious occupations in the public sector (Kimble Citation1963, 62). Our investigation into opportunity costs supports this tentative conclusion. In 1937, farmers’ sons were beginning to enter government service and schooling could now offer the prospects of earnings beyond those available in farming (Austin Citation2005, 311). Cocoa farmers therefore began investing in their children’s education to qualify them for more lucrative jobs (Fortes, Steel, and Ady Citation1947, 165; Austin Citation2005, 311). Austin argues that for some cocoa-farming households that included school children, the labour inputs of children were in decline, both in per capita terms and cohort by cohort. Nevertheless, children’s labour contributions to cocoa production remained important throughout the colonial period and beyond (Austin Citation2005, 311–312).

Growing labour demand and more children from the south attending school meant that the cocoa sector became increasingly reliant on migrant child labour. Cocoa head loading did not stop with the development of transport as colonial officials had anticipated and suggestions that legislations should be passed to halt the employment of children were deemed unfeasible (Van Hear Citation1982b). With a revival of the cocoa industry in 1935, after the slump, more children were reportedly accompanying adult labourers to work on cocoa farms. Initially, they helped the adults to cultivate their food farms, thus freeing the adults to do the more difficult cocoa work. Children also head loaded harvested cocoa to marketing stations. In addition, children from the north were directly recruited to the south under annual and other forms of labour contract (Van Hear Citation1982a, 501). The Chief Commissioner of the Northern Territories described the practice to the Colonial Secretary:

These labourers are frequently youths of 14 or 15 with no previous experience of work or conditions in the South who leave their homes without the knowledge or consent of their parents. In some cases, written agreements are made but, in most cases, it is only verbal.Footnote29

There are various indications that the regional gap persisted in the 1950s and that it was primarily families in the south who perceived that the opportunity costs had started to change in favour of schooling. In primary and middle schools in Accra in 1954, over 90% of the children enrolled were from the southern coastal towns (Foster Citation1965, 119–121). In 1956–c.1958, Bray (Citation1959, 42), in a survey of Ahafo, in then west Ashanti, found that out of the 839 offspring of cocoa-faming families, 30 had finished school and 239 were at school.

Estimating the role of opportunity costs is, however, difficult. As a final note, I refer to Foster’s argument that while one cannot disregard poverty and opportunity costs as causes of low school enrolment, the low assessment of educational investment as against alternative traditional forms of expenditure such as funerals was more significant. In addition, he concludes from some rural and urban surveys that in 1960, non-school-going children while ‘performing duties at home did not do so much more than school-going children as would justify their non-attendance in school’ (Foster Citation1965, 123). Admittedly, for some Ghanaian children education did not necessarily replace work but ran parallel to it and this coexistence was usually uneasy as colonial officials often bemoaned low attendance and high drop-out rates (Busia Citation1950, 52; Acquah Citation1958, 75–77; Lord Citation2015, 348).

Monetary costs

Aside from opportunity costs, there were monetary costs that deterred investment in education. Parents who wanted to enrol their children in school had to pay for fees, supplies, and uniforms, and many could not afford them. Even in the relatively more prosperous Asante, school fees featured prominently in conjugal negotiations and were a constant source of conflict between parents (Kaye Citation1962, 180–181; Allman and Tashjian Citation2000, 33, 91).

In the north, school fees might not have been as much a deterring factor for investment in education as they were in the south. No fees were collected until the 1930s when boarding institutions were established and annual fees ranging between 30 and 50 shillings per child were charged (Bening Citation1990, 16). Still, many of the schools in the Northern Territories did not have suitable accommodation, and pupils who had to travel long distances to school encountered boarding, lodging, and feeding problems. Although parents initially received a penny a day for their children attending school, problems with accommodation and feeding constrained school attendance and enrolment. Pupils who did not have relatives in the towns where they schooled often became houseboys for their hosts and rendered domestic services in exchange for lodging (Bening Citation1990, 13–14, 16).

Increasing shares of children enrolled in school (see ) can be partly explained by more parents in the south being able to pay the monetary costs, and that this ability was directly dependent on the development of cocoa prices. In an annual report from 1936, the colonial administration attributed the rise in demand for education to parents’ more prosperous conditions due to the better prices obtained during the last cocoa season.Footnote30 Schools filled up when cocoa trade was good and parents had money to spend on schooling and in bad times, school attendance dropped. Colonial officials observed:

Education is generally still looked upon as a luxury to be indulged in when there is money to spare over and above normal requirements, and this luxury is the first to be given up when less prosperous times necessitate economy.Footnote31

Table 3. Average expenditure on a senior school pupil in Sekondi-Takoradi, c. 1947–1948.

In some cocoa growing villages in Ashanti, the Gold Coast Colony and Trans-Volta Togoland, Hill based on data collected in 1954 to 1955, estimated the average annual educational expenditure to vary between £4 and £11 per child (see ). A further decomposition of the sample indicates that a large share of the respondents was in the low-income bracket, earning under £100 annually. In Tetrem, for example, about 41% of the 78 respondents earned up to £99 in the 1954–1955 cocoa season. In Nkwantakesse, 61% of the 56 respondents earned up to £99. In Kokoben and Asiakwa, where close to 80% of all the farmers had net incomes under £100, net cocoa income for this group of farmers was insufficient to even meet food expenditure (Hill Citation1956, 97).

Table 4. Cocoa farmers’ education expenditure in eight villages, 1954–1955.

Benefits of colonial education

I have shown in the previous section that costs deterred investment in colonial education. In this section, I argue that despite the high monetary and opportunity costs, there were limited occupational opportunities for school leavers and the returns to colonial education were insufficient to encourage investments in education. As Clemens (Citation2004) has argued for elsewhere, private benefits of education that influence parents’ decision to enrol their children in school or not largely depend on the perceived or real demand for skilled labour. In colonial Ghana, the demand for skilled labour was limited. Increasing cocoa prices from the 1930s onwards and general economic development, however, provided a capital injection to the economy resulting in expanding private and public sectors and subsequent growing demand for skilled labour. Having said that, growth and structural change were limited, and occupational opportunities overall remained exclusive. The section begins with a discussion on labour market opportunities and ends with an analysis of financial rewards to colonial education.

Children represented a form of security and insurance for the future and parents who made the effort to educate their children considered it a financial investment from which they expected returns when their children were in salaried jobs (Busia Citation1950, 57; Kaye Citation1962, 24, 181; Allman and Tashjian Citation2000, 47). Therefore, Ghanaian aspirations were oriented to clerical occupations in government or commerce, and more importantly, to the financial rewards accruing to them. In early twentieth-century Asante, catechists bewailed the fact that the growth in education and the attendant process of conversion to Christianity was inspired by the economic motives of aspirant men and women (Allman and Tashjian Citation2000, 30). Christian leaders observed that Christian scholars, after returning from Kumasi, ‘have quite other minds’. Rather than continue their course of study, they preferred to ‘become clerks, etc. as their mates in order to make money as quick as possible’.Footnote32 Colonial rule and the expansion of the economy did create such opportunities in the public sector, but they were few and exclusive. Unemployment of school leavers was a major social problem throughout the colonial era and beyond (Busia Citation1950, 61–63; Foster Citation1965, 64, 67, 93, 180–181).

Already by 1850, the supply of literates was exceeding the demand for their services and educated Africans were increasingly becoming anxious over prospects of employment (Kimble Citation1963, 93). Access to senior positions within the colonial administration was limited for highly educated Africans and monopolized by Europeans. Senior civil service expanded rapidly in the early years of the twentieth century but as it became easier to recruit Europeans for Gold Coast appointments, only a few Africans occupied senior civil service positions (Kimble Citation1963, 99). In 1908, while there were 274 officers listed, only five were Africans, and except for one, they were of relatively junior rank.

There were disparities between the rising output of schools and the low rate of expansion in the modern sector of the economy (Foster Citation1965, 9; 180–181; Szereszewski Citation1965, 21; 35; 39–41). Meanwhile, cocoa production became the biggest absorber of labour services. It is estimated that between 1901 and 1910, about 10 to 15% of the adult population were engaged ‘more than casually’ in cocoa farming (Szereszewski Citation1965, 57; Van Hear Citation1982b, 35–36). In 1911, cocoa cropping and investment alone absorbed approximately 185,000 people, with the total population of the Gold Coast Colony and Ashanti being 1.5 million (Szereszewski Citation1965, 57). In Amansie in Ashanti, Austin notes that by 1914–1915, as the ‘take-off’ phase of local cocoa planting approached its close, cocoa farms would have required at least a third, or even over a half, of the equivalent of the entire male labour force (Austin Citation2005, 417). This ‘cash crop revolution’ together with increased economic activity of the colonial administration and the mines, created a great demand for wage labour and a consequent shortage of unskilled labour (Van Hear Citation1982b, 33). At the same time, in the field of skilled labour there were occasional surpluses and even an exodus of skilled workmen to other African countries, albeit for shorter periods (Szereszewski Citation1965, 21, 35, 39–41). Demand for skilled services was met by the output of the apprenticeship system and increases in the scale of formal schooling (Szereszewski Citation1965, 40, 58).Footnote33

Opportunities for women were limited. Only 355 of the 97,237 women counted in urban areas in the 1931 census were among administrative and professional personnel (Cardinall Citation1931, 176).Footnote34 The limited employment opportunities available to girls was noted by women missionary educators in the late 1930s. In a ‘Memorandum on Women’s Work in the Gold Coast’ cited by Allman and Tashjian, Beer wrote:

The number of girls attending school has increased tremendously. These girls acquire a taste for European dress and amusements. They will not go home to the heavy manual work of the farm. There is little economic outlet for them. Some get accepted to train as nurses or teachers. A few get work at the Post Office or Telephone Exchange. But great numbers fail to find any wage-earning occupation. Of these it is grievous to know that many are coming to our large towns, or to the mining centres, or roam from village to village, town to town as prostitutes. It is our problem in a sense because it is in one way a result of the education, we have given them.Footnote35

In 1960, after several decades of changes in the country’s occupational structure, 60% of the 2.56 million employed in the Ghanaian labour force were engaged in farming, fishing, forestry, and hunting, and 13% were engaged in small-scale trading activities, as contrasted with only 4.5% occupied in professional, administrative, technical, and clerical roles. Skilled jobs were mostly occupied by men in the south and structural inequalities in the labour market remained. In 1960, women accounted for only 20% of professional personnel. Except for trading, where women accounted for 28.2% of the employed labour force, men monopolized all other occupations.Footnote36

Occupational opportunities were also subject to regional differentiation (see ). Initially, Southerners monopolized all white-collar and semi-skilled jobs within the Northern Territories, but as more Northerners became trained, they increasingly took over (Ladouceur Citation1979, 59). Further, as a deliberate policy, only natives of the Protectorate were engaged on the Native Administration clerical staff.Footnote37 Therefore, in the north government employees, at least at the lower and middle levels, were increasingly of northern origin. This policy provided employment opportunities for the few educated Northerners (Ladouceur Citation1979, 59). There was, however, little or no expansion in the modern sector of the economy in the north (Szereszewski Citation1966). Throughout the colonial era, agriculture remained more important in the Northern Territories compared to the south and there were few people employed in non-traditional sectors of the economy.

Table 5. Main occupations of all employed persons aged 15 years and over by region, 1960.

We now turn to financial payoffs from colonial education. An examination of wage levels from the 1890s show that in the early decades of colonial rule, there were low financial rewards for the privileged few employed by the colonial administration. Up to 1896, the salary for government clerks ranged from £18 to £200 per annum. However, only four officers were at the top of the scale and more than 75% of the 233 clerks employed were receiving less than £80 per annum (Kimble Citation1963, 101). While a committee of inquiry in 1896 pegged the minimum annual salary at £36, the lowest possible cost of living was estimated to be about £45 per annum. This implied that unless their families supported them, some educated Africans could not live without running into debt (Kimble Citation1963, 101). African salaries remained static and for over 20 years the lowest grade continued to receive an amount that could not meet the cost of living. Demands for better emoluments and conditions of service continued throughout the early years of the twentieth century, but it was not until 1921 that the starting rate for African clerks was raised to £60.Footnote38

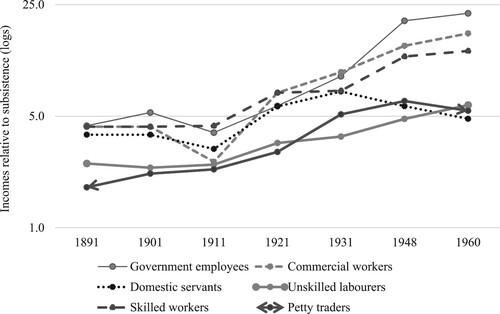

, based on Aboagye and Bolt’s (CitationForthcoming 2021) estimates, shows the evolution of incomes for six occupational groups in Ghana from 1891 to 1960. We observe no marked differences in wages of government employees and incomes of other occupations until the 1920s and 1930s.Footnote39 Tellingly, we can see how commercial workers’ incomes compared favourably with government employees’ wages. Therefore, although the returns to colonial education were high, there were immediate alternatives. Wages in the public sector, the sector which many Ghanaian school leavers were drawn to, increased substantially relative to other sectors only from the 1930s, when we observe an increase in enrolments and supply of education (see and ).

Figure 3. Evolution of incomes of workers relative to subsistence, 1891–1960. Source: Aboagye and Bolt (CitationForthcoming 2021).

A further look at skill premiums in indicate that educational skills were clearly at a premium as wages for skilled labour were higher than those in other sectors. The skill premiums are based on wages of government employees, and they range from 160 to 411% of unskilled wages. A high skill premium suggests that there is a high demand for skilled labour relative to unskilled labour, and this we would expect to positively influence investments in education. However, although the wages of skilled labour were higher than wages in other sectors, there were limited changes in the skill premium over time.

Table 6. Skill premium, annual wages (£).

In a recent study, Frankema and Van Waijenburg (Citation2019) observe a declining trend in skill premiums for various blue- and white-collar occupations in 50 African and Asian countries in the course of the twentieth century. For Ghana, the skill premium for clerks, for example, began to decline from the 1940s, from an average of 196% in 1920–1939 to 78% in 1940–1959 (2019, 100). Aboagye and Bolt’s (CitationForthcoming 2021) estimates are based on wages for single years while Frankema and Van Waijenburg’s (Citation2019) are based on averages over decades. This partly explains the difference in trend of both estimates. Nonetheless, both series show that although the demand for skilled workers increased steadily, supply kept pace with or even grew faster than demand. At the end of the colonial period, the relative cost of hiring skilled workers was lower than at the start (Frankema and Van Waijenburg Citation2019, 15). Admittedly, there were large material and social benefits associated with literacy and the learning of the metropolitan language particularly in the last decade of the colonial era. Fortes (Citation1948) observed that in Ashanti, for instance, increasing demand for education was related to the rising tendency to seek more satisfying and lucrative occupations than that of farming and the security for life, power and prestige white-collar jobs offered. Such opportunities, however, were confined to urban centres and major cities (Lord Citation2011, 96–98; Frankema Citation2012, 349).

Conclusion

Conventional views on the expansion of educational opportunities in colonial Africa have ascribed a dominant role to European policymakers and missionary societies and have had little place for the agency of the colonized people themselves. In relation to persistence in educational inequality, it has been argued that unequal provision of educational opportunities was a result of deliberate isolationist policies of the colonial state and the accidental character of missionary expansion. While this paper does not question that colonial policies and missionary activities had an impact, it has shown that the concrete outcome of said policies on educational development in colonial Africa cannot be fully understood without an analysis of the interaction with African responses. Further, it shows how indigenous agency depended on an evaluation of the costs and benefits of Western education.

In colonial Ghana, the critical roles children played in the household and in the accumulation strategies of parents and kinsmen, meant that the opportunity costs of educating children, particularly girls, were high. Meanwhile, in the Northern Territories where incomes were low and children assumed the role of absent adults in household production and other subsistence-oriented tasks, families had little or no incentive to educate their children. Further, monetary costs associated with schooling were often more than what many parents could afford. With increasing cocoa prices from the 1930s onwards and subsequent rising wages and incomes, however, a growing number of parents, particularly in the south, could afford to enrol their children in school. Existing regional and gender inequalities were further reinforced by changes in labour market structures and income levels that created differences in both opportunity costs and monetary costs.

In addition, the benefits of education were uncertain during the earlier decades of the colonial era, as the demand for skilled labour was limited and salary gains modest. Many school leavers could not find employment in the much sought-after public sector and unsurprisingly, enrolment rates stayed low. With the economic expansion from the 1930s onwards and a subsequent increase in demand for skilled labour and higher returns to colonial education, we found a significant increase in enrolment rates. Instead of a sequencing where education contributes to growth (Welch Citation1970; Romer Citation1990), we see that growth and associated expansion of economic opportunities eventually contributed to educational expansion. However, the underlying expectations that undergirded many parents’ decision to enrol their children in school were often not met and unemployment rates for school leavers remained substantial. Finally, expanding occupational opportunities in the colonial economy were primarily for the south, the public sector, in large towns, and for men. The educational sector mirrored these socio-economic inequalities, it did not alter them.

Acknowledgements

The author has benefitted from valuable comments and suggestions from two anonymous reviewers, and from Ellen Hillbom, Erik Green, Jeanne Cilliers, Jutta Bolt, Michiel de Haas, and participants in the panel session, ‘Gender and Inequality’ in the 2018 Annual Meeting of the African Economic History Network in Bologna, Italy, and the Development Lunch Seminar series at the Department of Economic History, Lund University, Sweden.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Census of Population, 1948, Report and Tables, p. 18.

2 Letter of 3 May 1876, from Rev. T. Picot, published in the African Times, 1 August and 1 September 1876: cited by Kimble (Citation1963, 75).

3 Annual Report of the Education Department for the Year 1952, 2.

4 Report of the Education Department for the Year 1900, 1; 4. There were two classes of assisted primary schools: (a) Government-established schools funded from public funds, and (b) schools established by missions and private persons but assisted from public funds.

5 Report on the Education Department for the year 1921; Census Report, 1921, 117.

6 Report on the Education Department, 1931.

7 Gold Coast, The Governor’s Address, Legislative Council Debates, 1928–1929, 15: cited by Foster (Citation1965, 124).

8 Differences in gross enrolment ratios between Lee and Lee (Citation2016) and Cogneau and Moradi (Citation2014) may be due to the fact that Cogneau and Moradi’s estimates are based on adjusted population numbers from the censuses.

9 Annual Report of the Education Department for the Year 1952, 5.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 Report on the Education Department for the Year 1951, 4.

13 Ibid., 3.

14 Ibid., Table 1, 31.

15 Author’s calculations based on Cardinall (Citation1931, 199).

16 Gold Coast, Census of Population 1948, 18. In the census classification, Standard III represents six years of primary education. Standard VII represents 10 years of education (Foster Citation1965, 118).

17 This is contrary to Foster’s (Citation1965, 121) assessment that unlike in Northern Nigeria, ‘few efforts were made to limit the activities of the missions’ in Ghana.

18 Colonial Secretary to Acting Chief Commissioner of the Northern Territories, 4 July 1905, NAG-A/ADM 56/1/33, cited by Bening (Citation1990, 21).

19 Missionary Council of the Church Assembly, 1926, 120, cited by Foster (Citation1965, 124).

20 Annual Report of the Education Department for the Year, 1952 5.

21 Ibid.

22 Report of the Education Department for the Year 1894, 6.

23 The Gold Coast Colony comprised the Western, Central, and Eastern Provinces. The child population are all children not above 15 years of age.

24 Report on the Northern Territories, 1914, 8.

25 CCNT to Secretary for Mines, 6 June 1922, NAG-A ADM 56/1/315, cited by Thomas (Citation1974, 99).

26 Freidrich Ramseyer to Governor, 31/10/1904, Domestic slavery in Ashanti, August 1904–1905, ARG 1/2/30/1/2, NAG Kumasi, cited by Lord (Citation2015, 61).

27 PRO CO 96/546/2608: ‘Child Cocoa Carriers’ 1 July 1914 cited by Van Hear (Citation1982a, 500).

28 Report on Ashanti for 1925–1926, p. 27.

29 Ghana National Archives, Tamale Adm. 1/301: ‘Slave Dealing’, cited by Van Hear (Citation1982a, 502).

30 Annual Administrative Report on Ashanti for 1936–1937, p. 14.

31 Ibid.

32 BMAD-1/186: ‘Report of Samuel Boateng’ Bompata, no date, probably 1905: cited by Allman and Tashjian (Citation2000, 30).

33 Apprenticeship to parents or a self-employed craftsman, carpenter, mason, or plumber was the most important ‘avenue for children to accumulate specialized and marketable human capital’ even in the late colonial era (Lord Citation2015, 324; see also Peil Citation1970).

34 Fifteen were listed as doctors, 150 as government civil servants, and 190 as teachers.

35 MMS, WW, Correspondence, Africa, Missionaries: Persis Beer, ‘Memorandum on Women’s Work in the Gold Coast’ (no date, perhaps 1938) cited by Allman and Tashjian (Citation2000, 200–201).

36 Census Report, 1960.

37 Annual Report on the Northern Territories for the Year 1936–1937, 17.

38 Dispatch of 1 November 1921, from Churchill to Guggisberg; ‘African Civil Service’, Sessional Paper No. 1 of 1922–1923.

39 See also Frankema and Van Waijenburg (Citation2012).

References

- Abdulai, Abdul-Gafuru, and Sam Hickey. 2016. “The Politics of Development Under Competitive Clientelism: Insights from Ghana’s Education Sector.” African Affairs 115 (458): 44–72.

- Aboagye, Prince Young, and Jutta Bolt. Forthcoming 2021. “Long-Term Trends in Income Inequality: Winners and Losers of Economic Change in Ghana, 1891–1960.” Explorations in Economic History.

- Acquah, Ioné. 1958. Accra Survey: A Social Survey of the Capital of Ghana, Formerly Called the Gold Coast, Undertaken for the West African Institute of Social and Economic Research, 1953–1956. London: University of London Press.

- Akurang-Parry, Kwabena O. 2002. ““The Loads are Heavier Than Usual”: Forced Labor by Women and Children in the Central Province, Gold Coast (Colonial Ghana), CA. 1900–1940.” African Economic History 30: 31–51.

- Akyeampong, Emmanuel, and Hippolyte Fofack. 2014. “The Contribution of African Women to Economic Growth and Development in the Pre-Colonial and Colonial Periods: Historical Perspectives and Policy Implications.” Economic History of Developing Regions 29 (1): 42–73.

- Allman, Jean, and Victoria Tashjian. 2000. ‘I Will Not Eat Stone’: A Women’s History of Colonial Asante. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

- Archer, Margaret Scotford. 1979. Social Origins of Educational Systems. Beverly Hills: Sage.

- Austin, Gareth. 1994. “Human Pawning in Asante c.1820–c.1950: Markets and Coercion, Gender and Cocoa.” In Pawnship in Africa: Debt Bondage in Historical Perspective, edited by Toyin Falola and Paul E. Lovejoy, 119–159. Boulder, San Francisco and Oxford: Westview Press.

- Austin, Gareth. 2005. Labour, Land, and Capital in Ghana: From Slavery to Free Labour in Asante, 1807–1956. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer.

- Baten, Joerg, Michiel de Haas, Elisabeth Kempter, and Felix Meier zu Selhausen. 2020. “Educational Gender Inequality in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Long-Term Perspective.” African Economic History Working Paper Series No. 54.

- Becker, Gary S. 1964. Human Capital. New York: Columbia University Press for NBER.

- Benavot, Aaron, and Phyllis Riddle. 1988. “The Expansion of Primary Education, 1870–1940: Trends and Issues.” Sociology of Education 61 (3): 191–210.

- Bening, R. Bagulo. 1990. A History of Education in Northern Ghana. Accra: Ghana University Press.

- Boli, John, Francisco O. Ramirez, and John W. Meyer. 1985. “Explaining the Origins and Expansion of Mass Education.” Comparative Education Review 29 (2): 145–170.

- Bolt, Jutta, and Dirk Bezemer. 2009. “Understanding Long-Run African Growth: Colonial Institutions or Colonial Education?” The Journal of Development Studies 45 (1): 24–54.

- Bray, Frank R. 1959. Cocoa Development in Ahafo, West Ashanti. Achimota: University of Ghana.

- Brown, David S. 2000. “Democracy, Colonization, and Human Capital in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Studies in Comparative International Development 35 (1): 20–40.

- Busia, Kofi Abrefa. 1950. Report on a Social Survey of Sekondi-Takoradi. Accra: Government of the Gold Coast Printing Department.

- Cardinall, Allan Wolsey. 1931. The Gold Coast, 1931. Accra: Gold Coast Government Printer.

- Clemens, Michael A. 2004. “The Long Walk to School: International Education Goals in Historical Perspective.” Center for Global Development Working Paper No. 37.

- Coe, Cati. 2012. “How Debt Became Care: Child Pawning and its Transformations in Akuapem, the Gold Coast, 1874–1929.” Africa 82 (2): 287–311.

- Cogneau, Denis, and Alexander Moradi. 2014. “Borders That Divide: Education and Religion in Ghana and Togo Since Colonial Times.” The Journal of Economic History 74 (3): 694–729.

- Coleman, James, ed. 1965. Education and Political Development. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Craig, John E. 1981. “Chapter 4: The Expansion of Education.” Review of Research in Education 9 (1): 151–213.

- Cunningham, Hugh. 2000. “The Decline of Child Labour: Labour Markets and Family Economies in Europe and North America Since 1830.” The Economic History Review 53 (3): 409–428.

- De Haas, Michiel, and Ewout Frankema. 2018. “Gender, Ethnicity, and Unequal Opportunity in Colonial Uganda: European Influences, African Realities, and the Pitfalls of Parish Register Data.” The Economic History Review 71 (3): 965–994.

- Dupraz, Yanick. 2019. “French and British Colonial Legacies in Education: Evidence from the Partition of Cameroon.” The Journal of Economic History 79 (3): 628–668.

- Engerman, Stanley L., and Kenneth L. Sokoloff. 2002. “Factor Endowments, Inequality, and Paths of Development among New World Economics.” National Bureau of Economic Research No. w9259.

- Feldmann, Horst. 2016. “The Long Shadows of Spanish and French Colonial Education.” Kyklos 69 (1): 32–64.

- Fortes, Meyer. 1938. Social and Psychological Aspects of Education in Taleland. London: Oxford University Press.

- Fortes, Meyer. 1948. The Ashanti Social Survey: A Preliminary Report. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fortes, Meyer, R. W. Steel, and P. Ady. 1947. “Ashanti Survey, 1945–46: An Experiment in Social Research.” The Geographical Journal 110 (4/6): 149–177.

- Foster, Philip. 1965. Education and Social Change in Ghana. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Frankema, Ewout. 2012. “The Origins of Formal Education in Sub-Saharan Africa: Was British Rule More Benign?” European Review of Economic History 16 (4): 335–355.

- Frankema, Ewout, and Marlous Van Waijenburg. 2012. “Structural Impediments to African Growth? New Evidence from Real Wages in British Africa, 1880–1965.” The Journal of Economic History 72 (4): 895–926.

- Frankema, Ewout, and Marlous Van Waijenburg. 2019. “The Great Convergence, Skill Accumulation and Mass Education in Africa and Asia, 1870-2010.” Centre for Economic Policy Research Discussion Paper DP14150.

- Gallego, Francisco A. 2010. “Historical Origins of Schooling: The Role of Democracy and Political Decentralization.” Review of Economics and Statistics 92 (2): 228–243.

- Gallego, Francisco A., and Robert Woodberry. 2010. “Christian Missionaries and Education in Former African Colonies: How Competition Mattered.” Journal of African Economies 19 (3): 294–329.

- George, Betty Stein. 1976. Education in Ghana. Washington, DC: Office of Education.

- Glaeser, Edward L., Rafael La Porta, Florencio Lopez-de-Silanes, and Andrei Shleifer. 2004. “Do Institutions Cause Growth?” Journal of Economic Growth 9 (3): 271–303.

- Goldin, Claudia Dale, and Lawrence F. Katz. 2008. The Race Between Education and Technology. London: Harvard University Press.

- Graham, Charles Kwesi. 1968. “The Educational Experience of the Fanti Area of the Gold Coast (Ghana) in the 19th Century. A Study in Social Structure and Social Change.” PhD diss., University of London.

- Graham, Charles Kwesi. 1971. The History of Education in Ghana: From the Earliest Times to the Declaration of Independence. London: Frank Cass and Co. Ltd.

- Grier, Robin M. 1999. “Colonial Legacies and Economic Growth.” Public Choice 98 (3-4): 317–335.

- Hill, Polly. 1956. The Gold Coast Cocoa Farmer: A Preliminary Survey. London: Oxford University Press.

- Huillery, Elise. 2009. “History Matters: The Long-Term Impact of Colonial Public Investments in French West Africa.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 1 (2): 176–215.

- Hurd, G. E. 1967. “Education.” In A Study of Contemporary Ghana: Volume 2, Some Aspects of Social Structure, edited by Walter Birmingham, Ilya Neustadt, and Emmanuel N. Omaboe, 217–239. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

- Jedwab, Remi, Felix Meier zu Selhausen, and Alexander Moradi. 2018. “The Economics of Missionary Expansion: Evidence from Africa and Implications for Development.” CSAE Working Paper WPS/2018-07.

- Kaye, Barrington. 1962. Bringing Up Children in Ghana: An Impressionistic Survey. London: Allen & Unwin.

- Kimble, David. 1963. A Political History of Ghana: The Rise of Gold Coast Nationalism, 1850–1928. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Ladouceur, Paul André. 1979. Chiefs and Politicians: The Politics of Regionalism in Northern Ghana. London: Longman.

- Lee, Jong-Wha, and Hanol Lee. 2016. “Human Capital in the Long Run.” Journal of Development Economics 122 (1): 147–169.

- Levhari, David, and Yoram Weiss. 1974. “The Effect of Risk on the Investment in Human Capital.” The American Economic Review 64 (6): 950–963.

- Lindert, Peter H. 2004. Growing Public: Social Spending and Economic Growth Since the Eighteenth Century. Volume 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lord, Jack. 2011. “Child Labor in the Gold Coast: The Economics of Work, Education, and the Family in Late-Colonial African Childhoods, c. 1940–57.” The Journal of the History of Childhood and Youth 4 (1): 88–115.

- Lord, Jack. 2015. “The History of Childhood in Colonial Ghana, c.1900–57.” PhD diss., SOAS, University of London.

- McWilliam, Henry Ormiston Arthur, and Michael A. Kwamena-Poh. 1975. The Development of Education in Ghana: An Outline. London: Longman.

- Meier zu Selhausen, F. 2019. “Missions, Education and Conversion in Colonial Africa.” In Globalization and the Rise of Mass Education, edited by David Mitch and Gabriele Cappeli, 25–59. Cham: Springer Nature.

- Peil, Margaret. 1970. “The Apprenticeship System in Accra.” Africa 40 (2): 137–150.

- Plange, Nii-K. 1979. “Underdevelopment in Northern Ghana: Natural Causes or Colonial Capitalism?” Review of African Political Economy 6 (15/16): 4–14.

- Psacharopoulos, George. 1981. “Returns to Education: An Updated International Comparison.” Comparative Education 17 (3): 321–341.

- Robertson, Claire C. 1984. Sharing the Same Bowl: A Socioeconomic History of Women and Class in Accra, Ghana. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Romer, Paul. 1990. “Human Capital and Growth: Theory and Evidence.” Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy 32 (1990): 251–286.

- Subramaniam, V. 1979. “Consequences of Christian Missionary Education.” Third World Quarterly 1 (3): 129–131.

- Szereszewski, R. 1965. Structural Changes in the Economy of Ghana, 1891–1911. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

- Szereszewski, R. 1966. “Regional Aspects of the Structure of the Economy.” In A Study of Contemporary Ghana: Volume 1, The Economy of Ghana, edited by Walter Birmingham, Ilya Neustadt, and Emmanuel N. Omaboe, 89–105. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

- Thomas, Roger G. 1974. “Education in Northern Ghana, 1906–1940: A Study in Colonial Paradox.” The International Journal of African Historical Studies 7 (3): 427–467.

- Tordoff, William. 1965. Ashanti Under the Prempehs: 1888–1935. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- UNESCO. 2019. “Education in Africa.” Accessed December 3, 2019. http://uis.unesco.org/en/topic/education-africa.

- Van Hear, Nick. 1982a. “Child Labour and the Development of Capitalist Agriculture in Ghana.” Development and Change 13 (4): 499–514.

- Van Hear, Nick. 1982b. “Northern Labour and the Development of Capitalist Agriculture in Ghana.” PhD diss., University of Birmingham.

- Welch, Finis. 1970. “Education in Production.” Journal of Political Economy 78 (1): 35–59.