ABSTRACT

Development economists have long studied the relationship between gender equality and economic growth. More recently, economic historians have taken an overdue interest. We sketch the pathways within the development literature that have been hypothesized as linking equality for women to rising incomes, and the reverse channels – from higher incomes to equality. We describe how the European Marriage Pattern literature applies these mechanisms, and we highlight problems with the claimed link between equality and growth. We then explain how a crucial example of technological unemployment for women – the destruction of hand spinning during the British Industrial Revolution – contributed to the emergence of the male breadwinner family. We show how this family structure created household relationships that play into the development pathways, and outline its persistent effects into the twenty-first century.

The relationship between gender equality and economic growth has been studied intensively by development economists. Belatedly, economic historians have come to the issue. In this paper, we sketch the mechanisms that link equality to growth within the development literature, identify some problems within and between the causal pathways, and suggest how economic history can provide additional insight. We explore a key historical episode, the widespread technological unemployment created by the mechanization of hand spinning, to challenge essentialist views of women’s economic activity and contribution to development.

Linking gender equality and economic growth in the present and past

Research using cross-country regressions and micro case studies suggests that improving women’s access to resources contributes to economic growth (Kabeer and Natali Citation2013; Gammage, Kabeer, and van der Meulen Rogers Citation2016; but see Duflo Citation2012). Unfortunately, there is less support for the reverse relationship, from growth to gender equality (Kabeer Citation2016), which is discouraging for researchers who were hopeful of discovering a ‘virtuous circle’. Moreover, the evidence for reverse causality is largely based on the experience of rich countries, making any relationship less relevant to development policy.

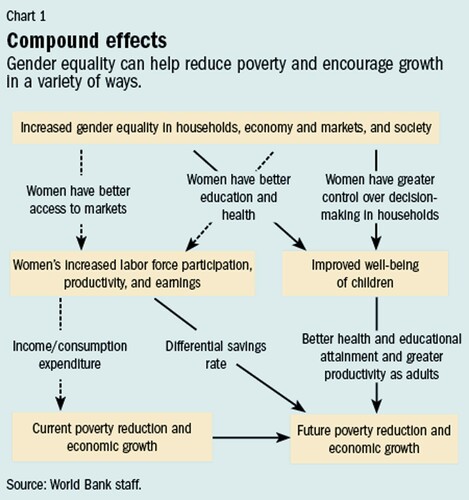

Stephan Klasen (Citation1999), an influential proponent of the view that gender equality enhances growth, identified two causal pathways. The first, a family-mediated pathway, holds that women are more likely to invest resources they control in their children’s human capital. Therefore, empowering women within households can enhance the productivity of the next generation. The second, a market-mediated pathway, assumes that competencies are randomly distributed between men and women, so the dismantling of gender bias will improve the efficient use of human resources. Both pathways involve women’s greater involvement in markets, particularly their increased labour force participation. These relationships are complicated, as the visualization from the World Bank suggests; numerous feedbacks and contingencies make identifying causation difficult. Nonetheless, initiatives that use female empowerment to enhance growth have become an important component of development policy (see e.g. World Bank Citation2013).

Figure 1. ‘Does gender inequality reduce growth and development’? Source: Morrison, Raju and Singha (Citation2007). CCBY License 3.01G0.

Economic historians have been less interested in gender than have their colleagues in development studies. The increasing influence of endogenous growth theory, with its prioritization of human capital formation, has belatedly encouraged more study of the historical role of women. Several highly cited papers revisited, and to some extent captured, an older theme and turned it to new account in an updated theory of European experience that places women’s empowerment and family allocations at its centre. De Moor and van Zanden (Citation2010) and Voigtländer and Voth (Citation2013) built on earlier influential work by Hajnal (Citation1965) to argue that the demographic catastrophe of the Black Death created a structural break in North West Europe’s economic history. The plague killed roughly 40% of the population, which produced unprecedentedly high wages and a shift in the distribution of income towards labour. In the English context, historians have described this development as a ‘Golden Age’ for the peasantry. Women shared in this sunlit era. For Voigtländer and Voth, women’s wages were boosted not only by the labour shortage but by the post-plague shift within agriculture, away from labour-intensive arable production to land-intensive pastoral production in which they had a comparative advantage. High wages and robust work opportunities, particularly for young women in life-cycle service, enhanced female autonomy and encouraged women to postpone marriage. For De Moor and van Zanden, these developments were consolidated by the growth of Protestantism and associated cultural changes.

The outcome was a new marriage pattern, the (North West) ‘European Marriage Pattern’ (EMP), with delayed marriage and higher rates of celibacy. The EMP embedded behavioural norms that reduced birth rates and therefore demographic pressure. Wages did not return to semi-subsistence levels, and as a result investment in the human capital of subsequent generations increased. England, in particular, accessed a higher growth trajectory uninterrupted by periods of retrenchment and unblighted by scarcity or mortality crises. As a result, Europe saw a ‘Little Divergence’ whereby the Western European countries on the North Sea moved ahead of the previous leaders, Spain and the Italian city states (Broadberry et al. Citation2015; Humphries and Weisdorf Citation2019). In England these developments culminated in industrialization. This historical account weaves together the two pathways to provide a complete account of gender equality’s positive relationship with growth. The exogenous pandemic and resulting tight labour market gave women better access to resources which then, through the EMP, provided a family pathway to improved productivity and enhanced growth.

Economic historians do not have access to the same kinds of evidence as development economists in their investigation of the relationship between gender equality and growth. The randomized control trials that increasingly dominate identification strategies in development studies are impossible, and even regression analyses require controls that strain available data sources. Not surprisingly, then, the historical version of the gender equality–growth pathway has been questioned. Some medievalists remain unconvinced that even a chronic labour shortage could have swept away the traditional constraints on women’s economic activities to the extent that the optimists imply (Bardsley Citation1999; Bennett Citation2010; but see Hatcher Citation2001). Nor is it clear that any expansion in pastoral agriculture by creating the conditions for delayed marriage resulted in fertility restriction, as in Voigtländer and Voth’s version of the pathway (see Edwards and Ogilvie Citation2021). Direct evidence of female access to higher wages or work in previously male employment is thin on the ground and, to the extent that it does exist, in England does not suggest any significant improvement in the status of women, particularly those engaged in life-cycle service (Humphries and Weisdorf Citation2015). The apparent inability of women servants to enjoy the benefits of the Golden Age is explainable by the power of paternalistic and patriarchal institutions. The landowner-controlled medieval state constrained the post-Black Death labour market with a series of laws (the Statute of Labourers) that sought to impose pre-plague employment conditions on workers. This oppressive legislation bore down particularly harshly on young women, who suffered the brunt of the state’s repressive reassertion of control over labour markets (Bennett Citation2010). More generally, the cross-section evidence on women’s wages over the long term does not suggest that gender inequality in the labour market was particularly severe in ‘left-behind’ Southern Europe (Drelichman and Gonzales Agudo Citation2020; Palma, Reis, and Rodrigues Citation2021; but see also de Pleijt and van Zanden Citation2021).

Authors have also doubted the strength and causal interpretation of the correlation between the EMP and subsequent growth experience (Bennett Citation2019; Dennison and Ogilvie Citation2019; Horrell, Humphries, and Weisdorf Citation2020; but see also Carmichael, de Pleijt, and van Zanden Citation2016; Bateman Citation2019; and Van Zanden, De Moor, and Carmichael Citation2019). It is not the aim of this paper to adjudicate across this rapidly growing literature. Rather, our intention is to identify tensions between the two pathways in their historical interaction and the resulting difficulties in combining them into a coherent account to complement the analysis in development studies. We now turn to a closer look at women’s role in the family pathway and its inconsistency with women’s increased labour force participation, productivity, and earnings as laid out in the market pathway.

Problems of the two pathways

In both the development and historical versions of the family pathway, women’s greater control over decision-making at the household level is associated with a reallocation of resources towards children. Behind this basic premise lurk fundamental assumptions about women’s role and position in families. As feminist economist Naila Kabeer has pointed out, ‘It is not “women” per se who drive these associations, but women in specific familial relationships, most often mothers and sometimes grandmothers’ (Kabeer Citation2016, 302; but see Becker Citation1981). Rather than an essential component of femininity, maternal selflessness is an ideological extension of gendered roles and responsibilities within households. Female altruism requires a distinctive gender division of labour in which women are primarily responsible for childcare and unpaid work in the home, which in turn entails some level of dependence on male incomes. Historically, such dependence is usually associated with male breadwinner families in which husbands and fathers were the principal earners and their jobs linked families to the economy (Janssens Citation1997). Although the origin and chronology of male breadwinning remains controversial, the standard account associates it with rising male wages, beginning roughly in the nineteenth century. This enabled wives and mothers to withdraw from the labour force and devote themselves to domestic work and childcare.

The reduction in female labour supply had beneficial implications for working-class living standards: children could be sent to school rather than work, which aided child well-being, human capital formation, and economic growth. Readers might recognize again some elements of Klasen’s family pathway. Alternatively, radical feminist historians have seen male breadwinner families as the patriarchal outcome of chauvinistic institutions that excluded women from paid work and rendered them dependent on husbands and fathers. Although these arguments continue, the male breadwinner structure did protect women from a double shift of both domestic labour and paid work, and, by freeing up their time for household and caring work, improved welfare for the household. However, any gains were at the expense of women who were reduced to dependence on men. Worse, in the many cases of failing breadwinners, families often fell into desperate poverty, and even in the best circumstances, dependency inhibited women’s agency and autonomy (Creighton Citation1996, Citation1999). Women’s domestic and caring roles, while ensuring their maternal altruism, prevented them from competing in the paid labour market and so promoting a more efficient allocation of human resources. Moreover, as markets came to index value, unpaid care work was belittled, and unpaid family members lost status as well as authority over the distribution of household resources.

Neoclassical economists argue that the male breadwinner family was the optimizing outcome of individual decisions as male wages rose. However, there are less benign interpretations of both its origins and consequences. We see the historical construction of gendered dependence as an important circuit breaker in the combined pathways’ creation of a virtuous circle of gender equality and economic growth. We investigate these relationships further in the context of a force that is underplayed in the literature cited above but ever present in accounts of economic growth: technological change. Our case study is the important but widely overlooked example of the mechanization of spinning. In this case, technological change and resulting unemployment was the source of the shock to the labour market. Like the Black Death, it had powerful implications for family structures, but in a different direction. These effects have been deeply regressive for gender equality while productivity-enhancing technology has increased economic growth. The case of the destruction of hand spinning and its role in the economic, social, and cultural creation of the male breadwinner family suggests why the claim that growth leads to greater gender equality may not only be weak, but can even function in reverse.

Technological change and family structure: The lost case of hand spinning

Technological unemployment is often seen as a non-issue in analyses of growth on the grounds that new jobs in new sectors will provide replacement work (Brynjolfsson and McAfee Citation2014; Bootle Citation2019). Over time, in macro terms, this may well be correct. But this dismissive stance ignores the fallout from technological change on family structures and particularly familial patterns of support and dependence. Household adaptations to job loss may be more durable than the initial labour market shock and long outlive the forces that produced them.

Although the chronology and causes of technological change remain controversial, no-one can deny its role in the Industrial Revolution (Mokyr Citation1990, Citation2002; Allen Citation2009). Nor, of course, can we overlook its widely discussed implications for the future of work, particularly anxiety about the threat of artificial intelligence replacing the dwindling number of decent jobs in the post-industrial Global North (Frey and Osborne Citation2017; Blanchflower Citation2019; Frey Citation2019; Benanav Citation2020). Our case study focuses on the neglected role of technological change, its destruction of jobs, and how technological unemployment has shaped dependence within families. Our historical illustration has been overlooked because it did not produce unemployment for men – heads of their households – but for women, whose contributions to household incomes were assumed – by contemporaries and historians – to be marginal. The mechanization of spinning drove hundreds of thousands of women from paid work and reshaped families throughout the industrializing world (Humphries and Schneider Citation2019, Citation2020). Though the effects of this dramatic shift persist, its origins are almost forgotten.

In pre-industrial economies, textile production was second only to agriculture in importance (Broadberry et al. Citation2015). Weaving was a common occupation for men, and the elimination of work on hand-looms by power looms led to falling wages and then disappearing jobs in the early nineteenth century. This job destruction is remembered through hundreds of accounts of the painful consequences (Bythell Citation1969). However, weaving required a steady supply of yarn, which had to be spun by hand on spinning wheels. Hand spinners were overwhelmingly women and children, employed on piece rates in an industry that grew as an employment share of the population throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. By 1750, perhaps as many as 20% of all women and children in Britain worked in spinning for at least part of the year (Muldrew Citation2012; Schneider Citation2015). After centuries of glacial technological progress, three machines rapidly increased the productivity of spinning in the 1760s and 1770s. The spinning jenny enabled a single worker to produce several yarns simultaneously; the spinning frame allowed for water (and later steam) power to supplant human muscle, and the spinning mule made it possible to produce finer yarns for higher quality fabrics (Fitton and Wadsworth Citation1958; Aspin Citation1968).

The spinning inventions and their organizational complement, the factory system, could produce far more yarn per worker than could hand spinners on wheels. This resulted in mass unemployment for women, only a small minority of whom found work in the new factories, while the government refused to limit the use of the new machines or to support the unemployed (House of Commons Citation1780). The British state accepted the mass unemployment of women in part because technological change in spinning improved the earnings of male weavers. This disruptive technology was catastrophic for women’s participation in market labour, for family incomes, and for women’s status in the household.

Although men had perhaps long been the major earners in most families, this loss of women’s opportunities to supplement incomes consolidated the male breadwinner family as a standard (Janssens Citation1997). The male breadwinner model offered working people a reflection of a family type that characterized their social superiors and so seemed an ideal to which to aspire. Once established among the working class in the early industrial age, the male breadwinner family persisted well into the 1900s. Critically, this family structure entrenched women’s primary responsibility for unpaid domestic and caring work. Its distribution of socially reproductive labour remained regardless of whether men earned enough to support their families, and whether women supplemented family incomes by paid work or subsistence activities.

The rapid elimination of women’s employment in hand spinning predated any substantial rise in male earnings. The male breadwinner family of industrializing Britain was the painful product of job destruction, not the happy outcome of human progress. It was forced on men and women, not chosen by them in perfect knowledge of the outcome. Job destruction produced widespread unemployment and destitution, which appeared in contemporary social surveys and poor relief bills. There was also a trap within the male breadwinner model: when families depended on workers who could not earn a ‘family wage’, they rapidly fell into poverty. This was clearly illustrated by the pioneering social science research of Charles Booth and Seebohm Rowntree at the end of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (Booth Citation1892–1897; Rowntree Citation1901).

The twentieth century, particularly the period after the Second World War, has witnessed dramatically increasing female participation rates in rich countries, including those of wives and mothers. However, there are persistent effects of the male breadwinning model in two parallel areas. First, the readjustment of responsibilities within families has been far slower. Although men’s participation in domestic work and childcare has increased, their take-up has not compensated for women’s engagement in market work. Most women continue to work a double shift. The underpinnings of the male breadwinner family in terms of relative participation rates and wages have been dramatically eroded, but women’s primary responsibility for caring and domestic work has continued. Second, there are institutional legacies: the British welfare state and the implicit social contract between genders and generations was built on the assumption that women would care for both the elderly and the young without pay, while men would earn wages that were sufficiently high and regular to provide support (Shafik Citation2021).

These two legacies have significant ramifications. First, they feed back into the labour market. Discontinuities in women’s employment records are the single biggest drivers of the persistent wage gap in Britain (Olsen et al. Citation2018). Employment gaps resulting from caring responsibilities continue to persuade employers that women will be less committed workers who are distracted by other obligations, making women less likely to be promoted. These effects impede the effective use of women’s human capital and progress along the market pathway to higher growth. Second, unequal responsibility for domestic labour and childcare means that women’s increased labour force participation has come about as they have taken up part-time, short hours, and home-based employment. This work is usually poorly paid and lacks benefits, but is more easily accommodated within domestic timetables and so is often chosen, if not necessarily preferred, by women. More recently, new technologies have spread such work practices to job categories (middle management) that were previously thought immune (Frey and Osborne Citation2017; Boushey Citation2019). Men as well as women in many middle-income jobs have been required to be more ‘flexible’ (Karamessini and Rubery Citation2014). Many jobs that previously paid ‘family wages’ have disappeared and more families are now dependent on multiple earners working several jobs, often on precarious contracts and with reduced security and support. On the other hand, work at the top of the income distribution has come to demand inflexible schedules, which are incompatible with the continuing social expectation that women will be the primary contributors to household labour. The exclusion of women from these high-income roles is another factor that contributes to continuing wage inequality (Goldin Citation2021).

While men have begun to increase their share of unpaid work, equality is still distant. Household surveys during the COVID-19 lockdowns have clearly illustrated the continuing inequality of unpaid work, and this gender inequality has been compounded by the greater direct economic impact on face-to-face occupations that disproportionately employ women, a phenomenon described in the media as a ‘shecession’. Responses to the pandemic have revealed how an outdated family structure continues to determine the allocation of work within families, based on gendered ideas about appropriate family behaviour. The crisis, with additional care work, homeschooling, and the lack of extrafamilial day care or child minding, has reinforced these social expectations. The pandemic’s burdens, unfairly dumped on women, will likely set back their gains in labour markets and families for years, if not decades (Kabeer, Razavi, and van der Meulen Rodgers Citation2021).

Conclusions

Recent historical analyses of women’s role in economic growth echo the pathways identified by development economists that link gender equality with economic progress. However, we have argued that the female altruism crucial to these pathways reflects a socially constructed gender role which has persisting adverse implications for women: their primary responsibility for caring work. We show that in an important historical case, women’s loss of remunerated work contributed to the idealization of this allocation of duties and to the household structure it embodied. This division of labour was not the result of some essential predisposition but the consequence of technological unemployment for a large swathe of women workers whose fate attracted little attention at least partly because they were women. This job destruction played a key role in the founding and spread of ideas about family organization that have had long-lasting and pervasive effects, which are embedded in cultural constraints and labour market and welfare institutions.

While our example is historically specific, the destruction of textile outworking had similar effects in other parts of Europe (Terki-Mignot Citation2021), and even restructured local employment opportunities and family divisions of labour in imperial dependencies (Nederveen Meerkerk Citation2021). Technological progress also threatens intermediate steps on the development ladder in present-day low-income countries (Rodrik Citation2016), and the reshoring of sectors such as textile production to rich countries could have important consequences for women’s paid labour opportunities. The example of job destruction in hand spinning illustrates that any household division of labour and paid work, whether the male breadwinner family or another model, is not the result of essentialized gender characteristics. The unfair burden of family responsibilities everywhere disrupts the positive effects of gender equity on growth and well-being, and breaks the virtuous circle of development and equality.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Allen, R. C. 2009. The British Industrial Revolution in Global Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Aspin, C. 1968. “Documents and Sources II: New Evidence on James Hargreaves and the Spinning Jenny.” Textile History 1: 119–121.

- Bardsley, S. 1999. “Women’s Work Reconsidered: Gender and Wage Differentiation in Late Medieval England.” Past and Present 165: 3–29.

- Bateman, V. 2019. The Sex Factor: How Women Made the West Rich. London: Polity Press.

- Becker, G. 1981. A Treatise on the Family. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Benanav, A. 2020. Automation and the Future of Work. London: Verso.

- Bennett, J. 2010. “Compulsory Service in Late Medieval England.” Past and Present 209: 7–51.

- Bennett, J. 2019. “Wretched Girls, Wretched Boys and the European Marriage Pattern in England (c. 1250–1350).” Continuity and Change 34: 315–347.

- Blanchflower, D. G. 2019. Not Working: Where Have all the Good Jobs Gone? Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Booth, C. 1892–1897. Life and Labour of the People in London. London: Williams and Norgate.

- Bootle, R. 2019. The AI Economy: Work, Wealth, and Welfare in the Robot Age. London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

- Boushey, H. 2019. Unbound: How Inequality Constricts Our Economy and What We Can Do About It. London: Harvard University Press.

- Broadberry, S. N., et al. 2015. British Economic Growth, 1270–1870. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Brynjolfsson, E., and A. McAfee. 2014. The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

- Bythell, D. 1969. The Handloom Weavers: A Study in the English Cotton Industry During the Industrial Revolution. London: University Press.

- Carmichael, S., A. M. D. de Pleijt, and J.-L. van Zanden. 2016. “The European Marriage Pattern and Its Measurement.” The Journal of Economic History 76: 196–204.

- Creighton, C. 1996. “The Rise of the Male Breadwinner Family: A Reappraisal.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 38: 310–337.

- Creighton, C. 1999. “The Rise and Decline of the Male Breadwinner Family in Britain.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 23: 519–541.

- Dennison, T., and S. Ogilvie. 2019. “Does the European Marriage Pattern Explain Economic Growth?” The Journal of Economic History 74: 651–693.

- De Moor, T., and J. L. van Zanden. 2010. “Girl Power: The European Marriage Pattern and Labour Markets in the North Sea Region in the Late Medieval and Early Modern Period.” The Economic History Review 63: 1–33.

- de Pleijt, A., and J-L. van Zanden. 2021. “Two Worlds of Female Labour: Gender Wage Inequality in Western Europe, 1300–1800.” The Economic History Review. https://ezproxy-prd.bodleian.ox.ac.uk:2102/https://doi.org/10.1111/ehr.13045

- Drelichman, M., and D. González Agudo. 2020. “The Gender Wage Gap in Early Modern Toledo, 1550–1650.” The Journal of Economic History 80: 351–385.

- Duflo, E. 2012. “Women Empowerment and Economic Development.” Journal of Economic Literature 50: 1051–1079.

- Edwards, J., and S. Ogilvie. 2021. “Did the Black Death Cause Economic Development by ‘Inventing’ Fertility Restriction?” Oxford Economic Papers, 1–19.

- Fitton, R. S., and A. P. Wadsworth. 1958. The Strutts and the Arkwrights, 1758–1830: A Study of the Early Factory System. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Frey, C. B. 2019. The Technology Trap: Capital, Labor, and Power in the Age of Automation. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Frey, C. B., and M. A. Osborne. 2017. “The Future of Employment: How Susceptible are Jobs to Computerisation?” Technological Forecasting & Social Change 114: 254–280.

- Gammage, S., N. Kabeer, and Y. van der Meulen Rogers, eds. 2016. “A Special Issue on Voice and Agency.” Feminist Economics 22.

- Goldin, C. 2021. Journey Across the Century of Women: The Quest for Career and Family. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Hajnal, J. 1965. “European Marriage Patterns in Perspective.” In Population in History, edited by D. V. Glass and D. E. C. Eversley, 101–43. London: Edward Arnold.

- Hatcher, J. 2001. “Debate: Women’s Work Reconsidered: Gender and Wage Differentiation in Late Medieval England.” Past and Present 173: 191–198.

- Horrell, S., J. Humphries, and J. Weisdorf. 2020. “Malthus’s Missing Women and Children: Demography and Wages in Historical Perspective, England 1280–1850.” European Economic Review 129: 103534.

- House of Commons. 1780. “Report from the Committee to Whom the Petition of the Cotton Spinners, and Others, in and Adjoining to the County of Lancaster; and Also The Petition of John Hilton, Agent for the Cotton Manufacturers of the Town and Neighbourhood of Manchester, on Behalf of the Said Manufacturers; Were Referred.” House of Commons Papers, 27 June 1780.

- Humphries, J., and B. Schneider. 2019. “Spinning the Industrial Revolution.” The Economic History Review 72: 126–155.

- Humphries, J., and B. Schneider. 2020. “Losing the Thread: A Response to Robert Allen.” The Economic History Review 73: 1137–1152.

- Humphries, J., and J. Weisdorf. 2015. “The Wages of Women in England, 1260–1850.” The Journal of Economic History 75: 405–447.

- Humphries, J., and J. Weisdorf. 2019. “Unreal Wages? Real Income and Economic Growth in England, 1260–1850.” The Economic Journal 129: 2867–2887.

- Janssens, A., ed. 1997. “The Rise and Decline of the Male Breadwinner Family.” International Review of Social History 42: 1–23.

- Kabeer, N. 2016. “Gender Equality, Economic Growth, and Women’s Agency: The “Endless Variety” and “Monotonous Similarity” of Patriarchal Constraints.” Feminist Economics 22: 295–321.

- Kabeer, N., and L. Natali. 2013. “Gender Equality and Economic Growth: Is there a Win-Win?” IDS Working Paper 417. Brighton.

- Kabeer, N., S. Razavi, and Y. van der Meulen Rodgers. 2021. “Feminist Economic Perspectives on Covid-19 Pandemic.” doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2021.1876906.

- Karamessini, M., and J. Rubery. 2014. Women and Austerity. The Economic Crisis and the Future for Gender Equality. London: Routledge.

- Klasen, S. 1999. Does Gender Inequality Reduce Growth and Development? Evidence from Cross-Country Regressions. Policy Research Report on Gender and Development. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Morrison, A., D. Raju, and N. Singha. 2007. “Gender Equality, Poverty and Economic Growth.” Policy Research Working Paper, No. 4349. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Mokyr, J. 1990. The Lever of Riches: Technological Creativity and Economic Progress. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mokyr, J. 2002. The Gifts of Athena: Historical Origins of the Knowledge Economy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Muldrew, C. 2012. “‘Th’ancient Distaff’ and ‘Whirling Spindle’: Measuring the Contribution of Spinning to Household Earnings and the National Economy in England, 1550–1770.” The Economic History Review 65: 498–526.

- Nederveen Meerkerk, E. 2021. “Relocation or Resilience? Household Textile Production and Consumption in Global Comparative Perspective.” Session at the European Social Science History Conference.

- Olsen, W., V. Gash, S. Kin, and M. Zhang. 2018. The Gender Pay Gap in the UK. Evidence from the UKHLS. London: Government Equalities Office.

- Palma, N., J. B. Reis, and L. Rodrigues. 2021. “Historical Gender Discrimination Does Not Explain Comparative Western European Development: Evidence from Portugal, 1300–1900.” CEPR Discussion Paper No. 15922.

- Rodrik, D. 2016. “Premature Deindustrialization.” Journal of Economic Growth 21: 1–33.

- Rowntree, B. S. 1901. Poverty: A Study of Town Life. London: MacMillan.

- Schneider, B. 2015. “Creative Destruction in the British Industrial Revolution: Hand Spinning to Mechanisation, c. 1700–1860.” MSc Thesis., University of Oxford.

- Shafik, M. 2021. What We Owe to Each Other. A New Social Contract. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Terki-Mignot, A. 2021. “Patterns of Female Employment in Normandy.” Paper Presented at the European Social Science Conference.

- Van Zanden, J.-L., T. De Moor, and S. Carmichael. 2019. Capital Women: The European Marriage Pattern, Female Empowerment and Economic Development in Western Europe. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Voigtländer, N., and H.-J. Voth. 2013. “How the West “Invented” Fertility Restriction.” American Economic Review 103: 2227–2264.

- World Bank. 2013. Opening Doors: Gender Equality and Development in the Middle East and North Africa. Washington, DC: The World Bank.