Abstract

Background: The most recommended type of anaesthesia by many obstetric guidelines for Caesarean section (CS) is spinal anaesthesia. This to achieve a higher level of pain and comfort control for the patient during and after CS. Little scientific research has assessed mothers’ satisfaction with spinal anaesthesia.

Methods: This was a cross-sectional study conducted at the maternity unit of Tembisa Hospital, South Africa in March 2014.

Results: Overall satisfaction with spinal anaesthesia was 77.1%. The mean age (SD) was 27.9 (5.8) years. CS was mostly done as an emergency 63 (76.8%). The level of satisfaction varied greatly. There was a linear regression between age and answer scores regarding preoperative explanations (r = 0.2. R-squared = 0.05, p-value of 0.03. There was an association between preoperative explanations and gravidity (OR 13.1; CL 95%; CI 1.9–41.7; p = 0.0018). In perioperative time, elective CS was associated with verbal communication with the doctor administrating the spinal anaesthesia (OR 13.5; CL 95% CI 0.7–237.3; p = 0.0017). Pain at the injection site of lumbar puncture (OR 4; CL 95% CI 1.2–13; p = 0.025) and the atmosphere in the theatre (OR 4.1; CL 95% CI 1.1–15.5; p = 0.02) were determinant for future choice of spinal anaesthesia.

Conclusion: Integrating pre-anaesthesia explanations in antenatal care and pre-anaesthesia counselling during labour and the use of adequate medication to reduce discomfort, pain and shivering may increase maternal satisfaction with spinal anaesthesia for CS.

Keywords::

Introduction

More than 18.5 million babies are delivered by Caesarean section (CS) per year.Citation1 The most recommended type of anaesthesia by many obstetric guidelines for CS is spinal anaesthesia.Citation2 This is thought to achieve a higher level of comfort and pain control for the patient during and after the surgical procedure, offering safety for both the pregnant woman and the baby. Among the reasons for this preference are that it is easy to administer, it is relatively safe, it offers a reliable onset of anaesthesia with normally no effect on the unborn baby and it offers lower cost, early ambulation, breast-feeding initiation and reduced hospital stay as compared with general anaesthesia.Citation2–4 Patient satisfaction is defined as the individual's positive evaluation of a distinct dimension of health care.Citation5 Does this rational medical choice of spinal anaesthesia meet patients’ satisfaction? Ideally, preoperative patient education, intraoperative care and rational drug choice should improve the quality of care and bring the acceptability closer to 100%.Citation6

A major component of quality of health care is patient satisfaction and research has identified a clear link between patient outcomes and patient satisfaction scores.Citation7 During the last decade, patient satisfaction ratings have been highlighted as an important objective of health care: this ensures the quality of anaesthesia care, improves and intensifies the doctor–patient relationship, and can also be a marketing tool in terms of customer orientation.Citation8

Although patients receiving spinal anaesthesia demonstrated a high rate of patient satisfaction some dissatisfaction was also reported with the preoperative explanation due to labour pain, discomfort during operation, pain at the surgical site and back pain in the postoperative period.Citation9,Citation10

African studies showed a relative lower satisfaction rate compared to other studies.Citation10,Citation11 Income range and marital status were significant baseline determinants of maternal satisfaction with spinal anaesthesia care. Neonatal outcomes were also associated with satisfaction.Citation11

This study aimed to determine maternal level of satisfaction with spinal anaesthesia for CS.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional study conducted at the maternity unit of Tembisa Hospital, South Africa in March 2014. A representative sample size of 82 women was determined with a confidence level of 95% and confidence interval of 0.5. A systematic random sampling method was used, whereby every second woman who was operated on under spinal anaesthesia and only from the post-CS ward's register was selected for inclusion in the study. The data collected was structured, and self-reported. A self-administered validated questionnaire was modified from a previous study.Citation10 The intraoperative elements included pain, headache, dizziness, nausea and vomiting. The postoperative components included postoperative nausea and vomiting (POVN), backache, headache, surgical site pain within two hours after the operation and discomfort. Some elements were not directly related to any specific period and they were classified as other perioperative elements. These elements were: pain at the spinal injection site, operating conditions in the perioperative period, maintenance of verbal contact with the patient by the doctor, and perioperative shivering. There were four data collection times. As women stayed for three days in this public hospital after Caesarean section, data collection was done after every three days. In this way, data were collected from mothers on day 0, day 1 and day 2 post-Caesarean section, at every data collection time.

Data analysis

Data were primarily described using descriptive statistics. To calculate the difference in categorical variables, Fisher’s exact analysis was used. Statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

Ethical consideration

Permission to conduct the study was obtained from the Chief Executive Officer of Tembisa Hospital and ethical clearance was given by the Department of Health Studies Higher Degrees Committee of the University of South Africa (clearance number HSHDC/269/2013). Written consent was obtained from every respondent. Authorisation to use and modify the question was obtained from the previous authors.

Results

Baseline characteristics

In this study, the minimum age was 18 and the maximum was 40; the mean age (SD) was 27.9 (5.8) years. CS was mostly done as an emergency 63 (76.8%). The majority of patients were African (78, 95.1%), not married (60, 73.2%) and unemployed (53, 64.6%). Primigravidas numbered 25 (30.5%) ().

Table 1: Baseline characteristics

Level of satisfaction in general

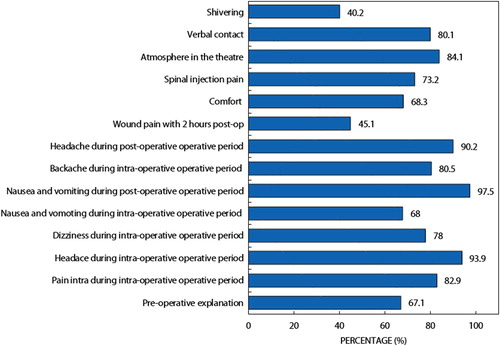

The level of satisfaction was as follows: pre-anaesthesia 55 (67.1%), intraoperative 73 (89%), postoperative 58 (71%) and perioperative 57 (70%). The elements of the different operative times varied greatly, ranging from 33 (40.2%) for shivering in the peri-operative period, to 89 (97.5%) for PONV in the intraoperative period. Overall satisfaction with the 15 components was 77.1% ().

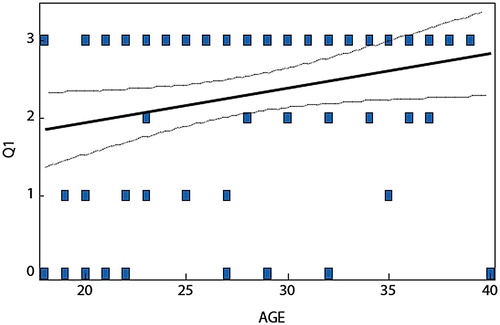

Preoperative explanation of spinal anaesthesia

The preoperative explanation of spinal anaesthesia to the participants was scored as follows: 3 for very clear explanation, 2 for clear explanation, 1 for unclear explanation and 0 for information not provided. The results showed that 55 (67.1%) were satisfied with the preoperative explanation. There was a linear regression between age and answer scores regarding preoperative explanations. The correlation coefficient was (r) = 0.2, R-squared = 0.05, with a p-value of 0.03 (). There was a significant relationship between gravidity and preoperative explanations (OR 13.1; CL 95%; CI 1.9–41.7; p = 0.0018) and between employment status and preoperative explanations (OR 4.7; CL 95% CI 1.4–15.7; p = 0.0071) ().

Table 2: Preoperative explanations (p-values below 0.05 are shown in bold)

Intraoperative elements

The level of maternal satisfaction with spinal anaesthesia for CS was assessed in terms of pain, headache, dizziness, nausea and vomiting. Different scores were chosen for these four intraoperative elements. Worst pain scored 0, strong pain scored 1, slight pain scored 2, no pain scored 3. Intraoperative headache was scored 0 for worst headache, 1 for strong, 2 for slight headache and 3 for no headache. Intraoperative dizziness was scored 0 for worst dizziness, 1 for strong dizziness, 2 for slight dizziness and 3 for no dizziness. Intraoperative nausea and vomiting was scored as follows: two times or more vomiting scored 0, vomiting once scored 1, nausea only scored 2 and no nausea and vomiting scored 3. All the elements were reduced to absent or no (3) and present or yes (0–2). Many participants (77, 93.9%) denied having headache. Nausea and vomiting satisfaction totalled 68 (82.9%), while satisfaction with dizziness was reported by 64 (78%). There was a significant relationship between marital status and satisfaction with nausea and vomiting (OR 0.2; CL 95%; CI 0.001–0.36; p-value < 0.0001) ().

Table 3: Intraoperative elements

Postoperative elements

The satisfaction level results for the postoperative components were as follows: PONV 80 (97.6%), headache 74 (90.2%), backache 66 (80.5%), discomfort 56 (68.3%) and surgical site pain within two hours after the operation 37 (45.1%). There was a significant relationship between employment (OR 11; CL 95%; CI 1.3–88.7; p = 0.0075) and backache, between employment (OR 11; CL 95% CI 0.6–198.3; p = 0.04) and headache, and between age and comfort (OR 0.2; CL 95%; CI 0.89–0.84; p = 0.002) ().

Table 4: Postoperative elements

Perioperative elements

The maternal satisfaction with spinal anaesthesia in terms of other perioperative findings was assessed through the following elements: satisfaction with pain at the spinal injection site, satisfaction with operating conditions in the perioperative period, satisfaction with verbal communication with the doctor and satisfaction with perioperative shivering. Participants were satisfied with operating conditions in the perioperative period (69, 83.1%). There was low satisfaction with shivering (33, 40.2%). There was a significant relationship between the types of CS and verbal communication with the doctor (OR 13.5; CL 95% CI 0.7–237.3); p = 0.0017) and between employment status and shivering (OR 5.3; CL 95% CI 1.9–14.1; p = 0.0009) ().

Table 5: Other perioperative findings

Acceptance of spinal anaesthesia in future

Many patients (68, 82.9%) reported that they will consent for spinal anaesthesia in future. A statistical significance was found between injection and future acceptance of spinal anaesthesia (OR 4; CL 95% CI 1.2–13; p = 0.025) and between the atmosphere in the theatre and future acceptance of spinal anaesthesia (OR 4.1; CL 95% CI 1.1–15.5; p = 0.02) ().

Table 6: Acceptance of spinal anaesthesia in future

Discussion

To assess the level of satisfaction with spinal anaesthesia, we grouped 15 components in 4 different anaesthesia periods: preoperative explanations, intraoperative, postoperative and perioperative. The satisfaction ranged from 67.1% (pre-anaesthesia) to 89% (intraoperative satisfaction). Many studies to assess spinal anaesthesia have reported high satisfaction, ranging from 85% to 100%.Citation2,Citation9,Citation10 The contrast between our findings and other studies may be explained by the number of components used. We assessed the satisfaction with spinal anaesthesia using 15 elements.

In our study, satisfaction with pre-anaesthesia information about the procedure was 67.1%, which is relatively low compared with Dharmalingam and Zainuddin (98%)Citation9 but higher than Shisanya and Marema (36%).Citation2 Low participant satisfaction with the explanation provided regarding spinal anaesthesia in our study can be explained by the fact that CS was mainly done as an emergency (76.8%) and most probably when the pregnant women were in labour. Satisfaction with pre-anaesthesia explanations was 73.7% among participants who underwent emergency elective CS, but it was 65.1% for emergency CS in our series. Other authors reported that patients could not concentrate on the explanation because of labour pain.Citation2,Citation9 Besides pain, Shisanya and Marema reported that no pre-anaesthesia visit caused low satisfaction with pre-anaesthesia explanations.Citation9 The linear regression between age and answer scores regarding preoperative explanations showed that the younger they were, the less they understood (p-value 0.03). The bivariate analysis also showed multigravida were more likely to be satisfied with preoperative explanations (OR 13.1 and p = 0.0018), the same as participants who were working (OR 4.7 and p = 0.0071). This would support that a certain level of maturity and serenity is needed to achieve a high degree of satisfaction with pre-anaesthesia explanations. Headache was qualified by some authors as the cause of discomfort from spinal anaesthesia. In our study, intraoperative headache recorded the highest satisfaction (93.9%), which concurred with the findings of Rani et al.Citation12 Univariant analysis did not show any significance. Postoperative components demonstrated a high level of satisfaction, such as 97.6% for PONV, 90.2% for headache and 80.5% for back pain, which is in keeping with many other studies.Citation9 But disappointing results were recorded for discomfort (68.3%) and pain (45.1%) at the surgical site after two hours. Discomfort after spinal anaesthesia was reported to be caused by the inability to control the limbs. Bhattarai et al. reported the same observation.Citation6

Back pain remains a real problem in patient satisfaction after spinal anaesthesia. We had satisfaction of 80.5% and employed respondents were 11 times more likely to be satisfied with backache with a significant p-value of 0.0075, which concurs with Siddiqi and Jaffri, but contrasts with Shisanya and Morema.Citation2,Citation10 Although there are many other factors that can explain the difference, in our view low satisfaction with the pre-anaesthesia explanation could be the cause as it meant to inform patients about the possible pain to be expected. The status of employment had also the same odds ratio with headache satisfaction and a p value of 0.04. These two significant findings could be explained by the fact that headache and backpain are common in workers.

Considering the perioperative period, there was a significant relationship between the types of CS and verbal communication with the doctor administering the anaesthesia. For this component, patients who underwent elective CS were 13.5 times more likely to be satisfied with the doctor than for emergency CS (OR 13.5; CL 95% CI 0.7–237.3; p = 0.0017).

Shivering after spinal anaesthesia is a frequent event, which occurs in up to 55% of cases.Citation13 Maternal satisfaction with shivering during the perioperative period was the lowest in our study (40.2%) and univariate analysis showed a significant difference between employment status and shivering (OR 5.3, p = 0.0009). Most studies on maternal satisfaction with spinal anaesthesia did not report on shivering.Citation2,Citation9,Citation10 Appropriate drug should be considered to relieve patients’ shivering, which was reported to be caused by hypothermia due to redistribution of heat, mainly following vasodilation below the level of a neuraxial block.Citation14

Many patients (82.9%) reported that they will consent for spinal anaesthesia in future. Statistical significance was found between injection and future acceptance of spinal anaesthesia (OR 4; CL 95% CI 1.2–13; p = 0.025) and between the atmosphere in the theatre and future acceptance of spinal anaesthesia (OR 4.1; CL 95% CI 1.1–15.5; p = 0.02). The same observations are found in the literature.Citation15,Citation16

Conclusion

Overall satisfaction with spinal anaesthesia in our study was 77.1% using 15 components. Ideally, satisfaction closer to 100% should be the target. Satisfaction is a complex concept. Social, cultural and affective factors can influence one individual differently from another. As patient satisfaction rhymes with expectation, a clear understanding of the patient’s agenda adjusted to the anaesthesia encounter will help to increase satisfaction. Given the low satisfaction in pre-anaesthesia, justified by the high rate of emergency CS, one should consider integrating the explanation in the antenatal care, with pre-anaesthesia counselling during labour, as any labour is a potential CS. The use of adequate medication to reduce the discomfort, pain and shivering may increase maternal satisfaction with spinal anaesthesia for CS.

Limitations of the study

Only one public hospital was used to conduct this study. The study could have been conducted in two or more public hospitals and private hospitals so that generalisation could have been made to Gauteng province or to the other provinces of South Africa.

The study was conducted for only a short period of time, i.e. March 2014, and with a sample of only 82 respondents. The reasons for this are time, funds and academic constraints. A study to evaluate maternal satisfaction with spinal anaesthesia for CS could have been conducted for many months or for a two-year period for example, and with a larger number of respondents.

Satisfaction is a feeling, therefore non-quantifiable and subjective. The fact that data were collected on different postoperative days may have created some disparity.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- WHO. 2012. World Health statistics 2012. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/gho/publications/world_health_statistics/2012/en/

- Shisanya MS, Morema EN. Determinants of maternal satisfaction with spinal anaesthesia care for caesarian delivery at the Kisumu county Hospital. IOSR J Nurs Health Sci. 2017(6):91–5. http://doi.org/10.9790/1959-0601089195.

- Casey WF. Spinal anaesthesia – a practical guide the advantages of spinal anaesthesia disadvantages of spinal anaesthesia. U Anaesth. 2000;12(12):1–7. Retrieved from http://www.nda.ox.ac.uk/wfsa/html/u12/u1208_01.htm

- Teoh WH, Shah MK, Mah CL. A randomized controlled trial on beneficial effects of early feeding post-caesarean delivery under regional anaesthesia. Singapore Med J. 2007;48(2):152–7.

- Linder-Pelz S. Social psychological determinants of patient satisfaction: a test of five hypotheses. Soc Sci Med. 1982;16(5):583–9. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(82)90312-4

- Bhattarai B, Rahman TR, Sah BP, et al. Central neural blocks: a quality assessment of anaesthesia in gynaecological surgeries. Nepal Med Coll J. 2005 Dec;7(2):93–6.

- Morris BJ, Richards JE, Archer KR, et al. Improving patient satisfaction in the orthopaedic trauma population. J Orthop Trauma. 2014;28(4):e80–4. http://doi.org/10.1097/01.bot.0000435604.75873.ba.

- Usas E, Banevicius G, Bilskiene D, et al. Satisfaction with spinal anaesthesia service and pain management in early postoperative period in patients undergoing spinal lumbar hernia microdiscectomy. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2012;29:11. doi: 10.1097/00003643-201206001-00035

- Dharmalingam TK, Zainuddin NA. Survey on maternal satisfaction in receiving spinal anaesthesia for caesarean section. Malays J Med Sci. 2013 May;20(3):51–4.

- Siddiqi R, Jafri SA. Maternal satisfaction after spinal anaesthesia for caesarean deliveries. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2009 Feb;19(2):77–80. http://doi.org/02.2009/JCPSP.7780.

- Melese T, Gebrehiwot Y, Bisetegne D, et al. Assessment of client satisfaction in labor and delivery services at a maternity referral hospital in Ethiopia. Pan Afr Med J. 2014;17. http://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2014.17.76.3189.

- Rani A, Thapa S, Singh K. Maternal satisfaction and causes of dissatisfaction after spinal anaesthesia in caesarean cases - survey. Bmrjournals. 2014;1(1):1–3.

- Crowley LJ, Buggy DJ. Shivering and neuraxial anesthesia. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2008;33:241–52. doi: 10.1097/00115550-200805000-00009

- Kim YA, Kweon TD, Kim M, et al. Comparison of meperidine and nefopam for prevention of shivering during spinal anesthesia. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2013;64(3):229–33. http://doi.org/10.4097/kjae.2013.64.3.229.

- Muneer MN, Malik S, Kumar N, et al. Causes of refusal for regional anaesthesia in obstetrics patients. Pak J Surg 2016; 32(1):39–43.

- Rhee WJ, Chung CJ, Lim YH, et al. Factors in patient dissatisfaction and refusal regarding spinal anesthesia. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2010;59(4): 260–4. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2010.59.4.260