Abstract

Background: The consequences of obesity for physical health and non-communicable illnesses are well established, but the impact on psychosocial well-being in persons with obesity is much less understood. This study aimed to assess psychosocial constructs such as weight bias affecting the eating behaviours of persons with overweight and obesity attending a general practice in South Africa

Methods: An observational study was conducted at a private general medical practice situated in a peri-urban area of Durban, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. A sample of 100 persons with overweight and obesity, and with a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2, were recruited by a convenience sampling method. Frequency tables for BMI, sociodemographic factors, perceptions and eating behaviours were described. Spearman’s rank-order correlation was run to assess the relationship between sociodemographic factors, perceptions, knowledge, attitudes and eating behaviours.

Results: About 90% were below 60 years and 83% were females. The mean BMI of males was 41.7 kg/m2 (SD = 7.38) and of females was 39.9 kg/m2 (SD = 7.91). It was found that weight stigma (are overweight people discriminated against) and the average household income were associated with abnormal eating behaviours such as compulsive eating, obsession with eating and psychological problems. A significant correlation was demonstrated between ‘Are people with overweight discriminated against?’ and abnormal eating behaviours such as compulsive eating (p = 0.049), obsession with eating (p = 0.009) and psychological problems (p = 0.051)

Conclusion: Psychosocial factors such as weight bias affect the eating behaviours of persons with overweight and obesity in South Africa. Research should be done exploring promotion of the psychosocial well-being of patients while trying to manage their obesity.

Background

Obesity is widely considered as a chronic disease associated with stigmatisation and discriminationCitation1,Citation2 and has long been regarded by the general public as a consequence of personal choices. However, depending on weight perceptions by society and persons living with obesity, obesity may represent a positive imageCitation3–5 or a disadvantaged social positionCitation6,Citation7 and weight bias is influenced by complex values and beliefs that are dependent on national and cultural context.Citation8 Weight bias is defined as negative attitudes, beliefs and judgements towards persons based on their body size.Citation7 Weight bias can be differentiated into weight prejudice and weight discrimination,Citation9,Citation10 with weight prejudice reflecting attitude, and weight discrimination evidenced by behaviour patterns.Citation11,Citation12 Weight bias, weight stigma and weight prejudice are terms that have been used interchangeably, particularly when describing individuals based on their bodyweight. Although weight discrimination and prejudice are practised within societies,Citation13 internalised weight bias will give us a better understanding of this complex and multilevel interaction.Citation14 Studies have shown that individuals with obesity often face psychosocial obstacles such as weight stigmatisation within the family and society,Citation11,Citation15 including their own beliefs about themselves, triggering a range of negative outcomes including disordered eating behaviours.Citation16 In a recent study from a country in Western Europe it was found that 18.7% of people with obesity experienced stigma and for people with severe obesity the outcome was much higher at 38%.Citation17 Research involving the United States, Canada, Iceland and Australia showed similar levels of weight-biased attitudes across these countries.Citation18 Research in Africa,Citation19,Citation20 particularly in South Africa, has shown that persons with obesity can have a positive body image and acceptance of their large body size.Citation3–5 The psychological pathways underlying these negative and positive associations are not well understood.Citation21,Citation22

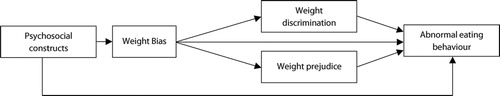

With the end of apartheid, South Africa experienced a social and economic transformation, and these were the driving factors for the increasing prevalence of obesity, more so among black South African women.Citation23 In a national study in South Africa in 2016, based on BMI score, two-thirds (68%) of all women were overweight or obese, and in contrast just under one-third of men (31%) were overweight or obese, with one in five women (20%) in the severely obese category; and only 3% of men severely obese.Citation24 Severe obesity was most common among coloured (mixed ancestry) and black/African women (26% and 20%, respectively) and the reported increases were due to increasing wealth quintile.Citation24 The stigma of HIV/AIDS and the positive body image, symbolising health, beauty, wealth and happiness was so strong that it had shaped cultural beliefs, particularly among black females.Citation3–5,Citation25 Despite this positive acceptance, persons with obesity still face weight bias, weight prejudice, stigmatisation and discrimination,Citation7,Citation12,Citation26 including social exclusion and inequities.Citation22 Thus, both the positive and negative psychosocial impact on obesity should be assessed and integrated into multidisciplinary interventions on weight management. The purpose of this study was to assess the impact of psychosocial constructs, specifically personal weight bias, weight prejudice and weight discrimination and their effect on eating behaviours of overweight and obese individuals in South Africa ().

Methods

This is a cross-sectional study of 100 consecutive participants with overweight and obesity attending a private family practice in a suburban area, north of Durban, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, and staffed by the principal investigator of this study. A family practice was deemed to be an ideal site for the study as participants would have had the opportunity to develop a trusting relationship with the principal investigator. The data collected were part of a Master’s dissertation and have been described in detail elsewhere.Citation5 The ethnic composition of the patients attending the family practice represented a heterogeneous, multi-ethnic and multicultural suburban population. It represented the ethnic demography described in the 2011 census for the province of KwaZulu-Natal, which comprised 86.81% Black African, 7.37% Indian, 4.18% White, 1.38% Coloured (mixed ancestry) and 0.26% Other.Citation27 Similarly, the family practice patient population comprised 64% Zulu, 30% of Indian origin and the remaining 6% were White, Coloured, Swazi and Xhosa.Citation5

Using a convenience sampling method, 100 participants with a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 who attended the practice and signed their informed consent were voluntarily recruited. To ensure standardisation, a single researcher administered to the participants between March and April 2014 the questionnaire that had been developed.

The questionnaire was developed following a review of the literature on overweight and obese persons’ perceptions, attitudes, knowledge and eating behaviour.Citation28,Citation29 The six topics in the questionnaire were based on previous studies on overweight and obese participants and included demographic profile (BMI, age, gender, education level, ethnicity, occupation, average household income, running water at home, electricity at home); perceptions of, knowledge of, and attitudes to obesity; eating patterns; dietary patterns; lifestyle choices, and chronic illnesses. In addition three additional topics identified from the self-reported questionnaire were sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, educational level, and average household income); BMI of the study participants; perceptions (If you know you are obese, is it because of choice, pressure from your partner, fear of HIV stigma or your culture regarding obesity as a sign of wealth and marital bliss? [Perceived reasons for obesity]; Does being overweight affect your sexual and personal relationship with your partner? Do you think that you are discriminated against because of being fat?); knowledge (Do you think that obesity is a health risk? Family history of obesity); attitudes (Have you tried to lose weight? Are you happy with your weight?) and eating behaviour (Are you inclined to binge often without being able to stop? Do you have a problem with compulsive eating [Meaning all the time/anytime]? Do you feel you have an obsession with eating [Meaning that you never stop thinking about food or what you are going to eat next]? Do you suffer from any psychological, psychiatric or emotional problem?) The questionnaire was reviewed by two additional family medicine specialists and pilot-tested for duration, clarity and suitability. Necessary modifications to shorten duration and improve clarity were made without compromising the quality of data collection on the various themes already outlined.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the Biomedical Research Ethics Council (BREC) in affiliation with the

University of KwaZulu-Natal. Full approval to conduct the study was granted (reference BE 239/13). Anonymity of participants was maintained throughout the study period and no personal identification details were included in data collection.

BMI classesCitation30

BMI was calculated as weight divided by height squared (kg/m2). Commonly accepted BMI ranges are those recommended by the World Health Organization: overweight (BMI 25–30 kg/m2), obese class I (BMI 31–35 kg/m2), obese class II (BMI 36–40 kg/m2) and obese class III (≥ 41 kg/m2) (WHO.) In addition to these standard BMI categories, individuals with class III obesity were further divided into three categories, BMI 41–45 kg/m2, BMI 46–50 kg/m2 and BMI > 50 kg/m2.

The data were coded and captured in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA, USA) and then transferred into the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 25; IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA) for analysis. Categories were meaningfully combined when indicated. Descriptive analysis of the sociodemographic and psychological factors was done. Spearman’s rank-order correlations were run to assess the relationship between psychological eating behaviour and the perceptions and knowledge of obesity and sociodemographic factors. Preliminary analysis showed the relationship to be monotonic, as assessed by visual inspection of a scatterplot.

Results

describes the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants. The sample comprised 100 overweight and obese participants of which close to 90% were under 60 years of age and 83% were females. The ethnic distribution of the participants was 64% Zulu and 30% of Indian origin with the remaining 6% being White, Coloured (mixed ancestry), Swazi and Xhosa. Around 94% of the study population had a BMI > 30 kg/m2. The mean BMI of males was 41.7 kg/m2 (SD = 7.38) and of females was 39.9 kg/m2 (SD = 7.91). Among the total participants, 79 had either a grade 12 or a tertiary qualification.

Table 1: Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants

describes the frequency results of the psychosocial determinants and eating behaviours. Nearly 90% of the study population stated that their body size was a personal choice and this result should trigger clinical concerns. More than half of the participants noted that their obesity affected intimacy with their partner and 77% stated that they were discriminated against for being obese ().

Table 2: Frequency results on perceptions, knowledge, attitudes and eating behaviour

depicts Spearman’s correlation between the sociodemographic characteristics and constructs of weight bias. Gender had a statistically significant relationship with overweight people being discriminated against and the effect of obesity on personal and sexual relationships.

Table 3: Correlations between sociodemographic factors and constructs of weight bias

shows the correlations between sociodemographic factors and eating behaviours. Significant correlations between sociodemographic factors and obsessive eating behaviour were demonstrated. looks at the correlations between weight perceptions and eating behaviours. A significant correlation was demonstrated between ‘Are people with overweight discriminated against?’ and abnormal eating behaviours. A significant correlation was demonstrated between ‘Are people with overweight discriminated against?’ and abnormal eating behaviours such as compulsive eating (p = 0.049), obsession with eating (p = 0.009) and psychological problems (p = 0.051).

Table 4: Correlations between sociodemographic factors and eating behaviours

Table 5: Correlations between weight perceptions and eating behaviours

Discussion

This study aimed to assess psychosocial constructs such as weight bias affecting the eating behaviours of persons with overweight and obesity in South Africa. The findings in this study present some contrasting results from previous studies in South Africa surrounding participants’ perceptions regarding weight/size. The findings underscore the necessity for further research, particularly around personal or internalised weight bias as a barrier to weight loss. A growing body of evidence shows that weight bias can have negative consequences leading to psychological impacts (such as internalised weight bias)Citation31 and behaviours (such as abnormal eating behaviours).Citation16 Although this study may show some correlations, the mechanisms underpinning these results is beyond the scope of this research.

We found that weight stigma (Are overweight people discriminated against?) and the average household income was associated with abnormal eating behaviours such as compulsive eating, obsession with eating and psychological problems. The relationship between weight stigma and abnormal eating behaviours has been supported in other studies.Citation6,Citation16,Citation32 Significantly, there is a negative correlation between the household income and eating behaviours and this may mean that the poorer one is, the more likely are abnormal eating behaviours. A previous study also concluded that females of lower socioeconomic status exhibited more signs of disordered eating behaviour.Citation33

When asked about their weight perceptions, most of the participants (83%) were unhappy with their weight and 77% felt discriminated against. This negative feeling toward their own bodyweight is described as internalised weight bias. This phenomenon has been researched and refers to the extent to which people accept and believe something as being true of themselves.Citation12 This is associated with negative outcomes including poor body image and abnormal eating behaviour, as shown in this study and elsewhere.Citation12

Although not happy with their weight and having tried to lose weight, the results showed that our participants made a personal choice to be obese. Research has shown that persons with a much higher level of internalised weight bias are likely to cope by refusing to diet, overeating or they display disordered eating behaviourCitation12 and the participants in this study seemed to have coped with weight bias in a similar way. These results further allude to the complexity of psychological functioning in persons with obesity. Studies have shown that the more individuals have negative weight experiences, the more likely they are to resort to maladaptive coping mechanisms.Citation12 Obesity and weight regain may be associated with emotional consequences, as seen in some of the results in this study, and individuals with obesity are more likely to be blamed when they are perceived to be personally responsible for their weight gain.Citation11 The link between perceptions of personal responsibility for obesity and weight bias has been convincingly demonstrated by Puhl et al.Citation34

Our results show that South Africans do consider obesity a health risk and participants are attempting to lose weight on their own but are failing to do so. Weight programmes advocating that persons eat less and exercise more are not enough because our participants have tried this before without success. These results are clinically significant and should alert healthcare professionals in weight management like a red flag. Obesity is a chronic disease and these patients should have access to evidence-based comprehensive obesity management programmes.

Much of the research on the cultural acceptance of obesity in South Africa was done during the HIV epidemic and post-apartheid.Citation3–5,Citation28 There is a preference for larger body size and a greater tolerance of increased body size among black South African women.Citation3 The findings in this study are demonstrating some shift away from the traditionally accepted cultural belief that ‘big is beautiful’Citation3 with 83% being unhappy with their weight. Even encouragement from their partners was only around 10% in this study, with 1% being associated with wealth as their reason for obesity. Given that media and health campaigns equate weight loss with being healthy, this concept increasingly exposes black South African women to conflicting body size ideals. Future studies should therefore monitor the effect of such influences on body size preferences.

Limitations

The strength of the study included that, to the best of our knowledge, this is a first study documenting internalised weight bias with abnormal eating behaviours. Although the present findings are interesting and sometimes a paradox, some issues limit their generalizability. We have focused on only obese and overweight and therefore the BMI range was limited, as was the choice of a self-selected convenience sample. The use of a structured questionnaire for the data collection on weight bias, perceived reasons for obesity and the participants’ eating behaviours is limited in its interpretations. Thus, based on a more pragmatic and less epistemologically oriented perspective, a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods would achieve more optimal results. This relatively small cross-sectional study sample performed on a single cohort of mainly female participants attending a general practice may have impacted on the findings and therefore might not be applicable to a larger population group.

Conclusions

These study results have shown that weight bias and particularly internalised weight bias are associated with abnormal eating behaviours. More research should be done exploring the promotion of psychosocial well-being of patients while trying to manage their obesity. The prevalence of weight bias and discrimination is high in other parts of the world and to date little is known about the prevalence and patterns of weight bias and discrimination in South Africa. Future research needs to be done to determine the extent of this, particularly in public spaces such as the workplace, schools, health institutions, etc.

Acknowledgements

Dr R Ramlal is acknowledged for her major contribution to the original research. The participants were thanked for their contribution to this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Authors’ contributions – All authors contributed equally to the final manuscript.

ORCID

References

- Kyle TK, Dhurandhar EJ, Allison DB. Regarding obesity as a disease: evolving policies and their implications. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecl.2016.04.004.

- James WPT. WHO recognition of the global obesity epidemic. Int J Obes 32. 2008;S120–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2008.247

- Puoane T, Fourie JM, Shapiro M, et al. ‘Big is beautiful’ – an exploration of urban black women in South Africa. South Afr J Clin Nutr. 2005;18(1):2221–8.

- Devanathan R, Esterhuizen T, Govender RD. Overweight and obesity amongst black women in Durban, KwaZulu-Natal: A ‘disease’ of perception in an area of high HIV prevalence. Afr J Prm Health Care Fam Med. 2013;5(1):17. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v5i1.450

- Ramlal R, Govender RD. More than scales and tape measures needed to address obesity in South Africa. SAFP. 2016;58(4):148–152. DOI:10.1080/20786190.2016.1151643

- Elfhag K, Morey LC. Personality traits and eating behavior in the obese: poor self-control in emotional and external eating but personality assets in restrained eating. Eating Behav. 2008;9:285–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2007.10.003

- Alberga AS, Russell-Mayhew S, von Ranson KM, et al. Weight bias: a call to action. J Eat Disord. 2016;4:34. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-016-0112-4

- Rosengren A, Teo K, Rangarajan S, et al. Psychosocial factors and obesity in 17 high-, middle- and low-income countries: the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiologic study. Int J Obes. 2015;39:1217–23. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2015.48

- Phul RM, Andreyeva T, Brownell KD. Perceptions of weight discrimination: prevalence and comparison of race and gender discrimination in America. Int J Obes. 2008;32:992–1000. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.22

- Lacroix E, Alberga A, Russell-Mathew MS, et al. Weight bias: a systematic review of characteristics and psychometric properties of self-report questionnaires. Obes Facts. 2017;10:223–37. https://doi.org/10.1159/000475716

- Andreyeva T, Puhl RM, Brownell KD. Changes in perceived weight discrimination among Americans, 1995–1996 through 2004–2006. Obesity. 2008;16:1129–34. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2008.35

- Hayward LE, Vartanian LR, Pinkus RT. Weight stigma predicts poorer psychological well-being through internalized weight bias and maladaptive coping responses. Obesity. 2018;26:755–61. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.22126

- Vartanian LR, Pinkus RT, Smyth JM. The phenomenology of weight stigma ineveryday life. J Contextual Behav Sci. 2014;3:196–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2014.01.003

- Cook JE, Purdie-Vaughns V, Meyer IH, et al. Intervening within and across levels: a multilevel approach to stigma and public health. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:101–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.09.023

- Phul R, Luedicke J, Peterson JL. Public reactions to obesity-related health campaigns a randomised controlled trial. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45(1):36–48. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.02.010

- O’Brien KS, Latner JD, Puhl RM, et al. The relationship between weight stigma and eating behavior is explained by weight bias internalization and psychological distress. Appetite. 2016;102:70–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.02.032

- Sikorski C, Spahlholz J, Hartlev M, Riedel-Heller S. Weight-based discrimination: an ubiquitary phenomenon? Int J Obes (Lond) 2016;40(2):333–37. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2015.165

- Puhl RM, Latner JD, O’Brien K, et al. A multinational examination of weight bias: predictors of anti-fat attitudes across four countries. Int J Obes (Lond) 2015;39(7):1166–73. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2015.32

- Holdsworth M, Gartner A, Landais E, et al. Perceptions of healthy and desirable body size in urban Senegalese women. Int J Obes. 2004;28:1561–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0802739

- Amoah AGB. Sociodemographic variations in obesity among Ghanaian adults. Public Health Nutr. 2003;6:751–7. doi: 10.1079/PHN2003506

- Wardle J, Cooke L. The impact of obesity on psychological well-being. Best practice & research. Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;19:421–440. DOI:10.1016/j.beem.2005.04.006

- Agrawal P, Gupta K, Mishra V, et al. The psychosocial factors related to obesity: a study among overweight, obese, and morbidly obese women in India. Women Health. 2015;55:623–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2015.1039180

- Reddy SP, Resnicow K, James S, et al. Underweight, overweight and obesity among South African adolescents: results of the 2002 national youth risk behaviour survey. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12:203–7. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980008002656

- South Africa Health Survey Demographic and Health Survey. (SADHS) 2016. [cited 2018 Oct. 5]. Available from: https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/Report%2003-00-09/Report%2003-00-092016.pdf

- Matoti-Mvalo T, Puoane T. Perceptions of body size and its association with HIV/AIDS. S Afr J Clin Nutr. 2011;24:40–45. doi: 10.1080/16070658.2011.11734348

- Henry J, Kollamparambil US. Obesity based labour market discrimination in South Africa: A dynamic panel analysis. ERSA,South Africa. 2017.

- Frith A. 2011. [cited 2018 Oct. 5]. Available from: https://census2011.adrianfrith.com/place/5. In census2011

- Mvo Z, Dick S, Steyn K. Perceptions of overweight African women about acceptable body size of women and children. Curatainis.1999;22:27–31.

- Micklesfield LK, Lambert EV, Hume DJ, et al. Socio-cultural, environmental and behavioural determinants of obesity in black South African women. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2013;24:369–75. https://doi.org/10.5830/CVJA-2013-069

- WHO. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO. 2000.

- Latner JD, Barile JP, Durso LE, et al. Weight and health-relatedquality of life: The moderating role of weight discrimination and internalized weight bias. Eat Behav. 2014;15:586–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.08.014

- Durso LE, Latner JD, White MA, et al. Internalized weight bias in obese patients with binge eating disorder: associations with eating disturbances and psychological functioning. Int J Eat Disord. 2012;45:423–27. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20933

- Gibbons P. The Relationship Between Eating Disorders and Socioeconomic Status: It's Not What You Think. Nutrition Noteworthy. 2001.

- Puhl R, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. Impact of perceived consensus on stereotypes about obese people:new avenues for bias reduction. Health Psychol. 2005;24:517–25. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.24.5.517