ABSTRACT

Background

Vitamin B12 is a micronutrient required for hematopoietic, neuro-cognitive and cardiovascular function. Biochemical and clinical vitamin B12 deficiency has been recognized in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. One of the adverse effects of long-term metformin use is vitamin B12 malabsorption. Aim of the study was to assess the state of vitamin B12 deficiency in people with type 2 diabetes and to ascertain the relationship between vitamin B12 status, metformin use and peripheral neuropathy. It is a retrospective study that was conducted on 8040 subjects included 2126 type 2 diabetic patients, and 5914 nondiabetic individuals. Personal information, medical history, including metformin and multivitamin therapy use as well as the existence of clinical peripheral neuropathy, were all included data. For the purpose of measuring the amount of vitamin B12, blood samples were taken. Serum B12 levels <200 pg/ml was defined as B12 deficiency.

Results

Vitamin B12 deficiency was detected in 12.9% of diabetic group and 19.9% of control group. The mean value of vitamin B12 level between diabetic (563 ± 470.6 pg/ml) and non-diabetic (429.7 ± 310.9 pg/ml) showed a high significant difference, p value <0.001. The vitamin B12 levels were higher in people with diabetes. Vitamin B12 deficiency was not associated with metformin intake or diabetic neuropathy.

Conclusions

Vitamin B12 level was significantly higher in diabetic compared to nondiabetic individuals. Neither peripheral neuropathy, anemia nor metformin therapy was associated with vitamin B12 deficiency. Vitamin B12 supplementation is not recommended as a routine practice in people with diabetes. This is contrary to the common practice that is sometimes done. The cost of supplementation can be used to provide more beneficial services and drugs for these people.

1. Introduction

Vitamin B12 is a water-soluble vitamin which shares a significant part in hemopoieses and neurological functions. Hematological and neurocognitive impairment are the main complications of vitamin B12 deficiency [Citation1]

Nearly 50% of diabetic people suffer from peripheral neuropathy. It raises the risk of leg ulcers, infections, fractures, amputations, severe changes in productivity, and increased use of medical services [Citation2,Citation3]. According to Gordois et al., annual expenses associated with neuropathy in the United States of America range from 4.6 to 13.7 billion dollars, or roughly one-third of those associated with diabetes [Citation4].

The physiological effects of vitamin B12 are mediated by two enzymatic mechanisms, the conversion of succinyl-CoA from methyl malonyl-Coenzyme A (CoA) and the methylation process that turns homocysteine into methionine. As a co-factor, vitamin B12 helps homocysteine be methylated into methionine, that is transformed to S adenosylmethionine. A lack of vitamin B12 impairs this conversion pathway, which raises levels of methylmalonic acid (MMA). Following this, neuronal membranes’ fatty acid secretion is compromised [Citation5]. Additionally is vitamin B12 necessary for the creation of monoamines, or neurotransmitters like serotonin and dopamine [Citation6]. Previously mentioned factors together account for the neurocognitive or mental symptoms that follow vitamin B12 insufficiency. Axonal demyelination and eventually death are hallmarks of vitamin B12 deficiency-induced neuronal injury, which presents as peripheral or autonomic neuropathy, subacute combined degeneration of spinal cord, delirium and dementia [Citation5–7].

A comparison of various cross-sectional studies [Citation8,Citation9] and case reports [Citation10,Citation11] revealed that type 2 diabetes individuals had increased incidence of vitamin B12 insufficiency.

Utilization of metformin has been conclusively shown to be the main contributing reason to vitamin B12 insufficiency in T2DM patients [Citation12,Citation13]. According to studies evaluating metformin treated patients, B12 insufficiency can occur in 5.8% to 33% of cases [Citation8,Citation13,Citation14].

Currently, according to ADA, NICE and EASD guidelines, there are no published recommendations in favor of routinely testing T2DM patients for vitamin B12 insufficiency (except in patients on metformin therapy). An annual overview of Medicare reimbursement rates for several laboratory tests was published by the United States Department of Health and Human Services. According to the information, testing for vitamin B12 level costs 21.59 dollars, testing for folate costs 21.06 dollars and testing for homocysteine costs 24.16 dollars [Citation15].

Despite low cost of vitamin B12 measurement, society bears a significant financial burden due to its frequent use. Without signs of pernicious anemia or in context of marked malnutrition, routine vitamin B12 testing may not be required [Citation16].

Periodic assessment of vitamin B12 may be taken into consideration in patients on metformin, particularly in those having anemia or neuropathy. Long-term metformin treatment (>4 years, 2 g/day) may be related with biochemical B12 deficiency [Citation17,Citation18].

There is no consensus on vit B12 deficiency cutoff values

For example the WHO definition is largely different. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), vitamin B12 status in adults is defined by the serum levels of the micronutrient with the following cutoffs and definitions: >221 pmol/L is vitamin “B12 adequacy;” between 148 and 221 pmol/L is “low B12,” and lower than 148 pmol/L (200 pg/ml) is “B12 deficiency” [Citation19].

1.1. Aim of the work

The current study was designed to determine the status of vitamin B12 level in type 2 diabetic patients and the association between serum vitamin B12 level and metformin therapy and clinical peripheral neuropathy.

2. Subjects and methods

This was a retrospective study with data retrieved from electronic medical records on ICARE database system in a general secondary hospital in Kuwait. The study was conducted on patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, in addition to non-diabetic subjects as a control group. This study gained approval by ethics committee. An informed consent was taken from all enrolled patients and the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki were followed.

The study included 8040 subjects divided into two groups: one group included 2126 diabetic patients and the other group included 5914 non-diabetic individuals.

The collected data included personal and medical history, such as age, gender, duration of diabetes, current medications, metformin use, current vitamin B12 replacement (orally or injection) and presence of peripheral neuropathy, nephropathy and retinopathy. Serum vitamin B12 levels were retrieved from the database.

2.1. Statistical analysis of the data

Data were entered into the computer and analyzed using the IBM SPSS software package, version 20.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). Numbers and percentages were used to present categorical statistics. In order to look into the relationship between the categorical variables, the chi-square test was performed. In the event when more than 20% of the cells have an expected count of less than 5, the Fisher Exact correction test was applied instead. Range, median, mean and standard deviation were used to show quantitative data. Two groups were compared using a Student's t-test. The 5% level of significance was used.

3. Results

A total number of 2126 persons with diabetes; 408 patients were on multivitamin therapy and 1718 patients were not receiving multivitamin therapy, 1131 patients were on metformin therapy.

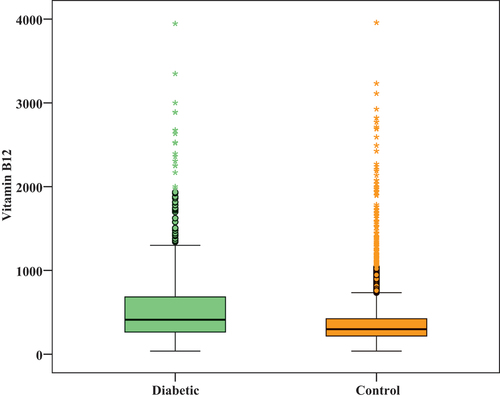

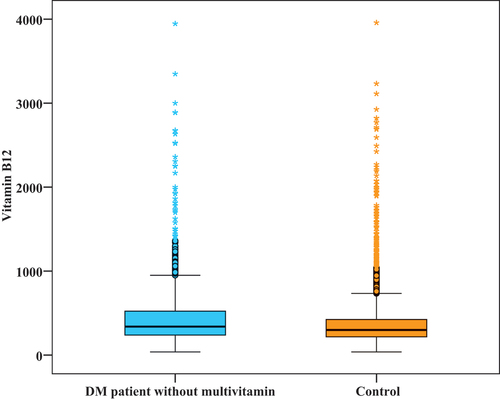

In our study, we identified 12.9% (275 patients) of diabetic patients with B12 deficiency when defined as a serum B12 level less than 200 pg/ml and 69.8% (192 patients) of them were on metformin therapy. As regard to the mean vitamin B12, patients with diabetes were not deficient compared to non-diabetic, moreover, diabetic patients who did not receive multivitamin supplementation (n = 1718) had significantly higher levels of vitamin b12 in comparison to control group(, ). Serum vitamin B12 was above the normal range level in 766 (36%) of the total patients with diabetes, including 358 patients (20.8%) not receiving multivitamin therapy and 408 patients on multivitamin therapy. .

Figure 1. Comparison between total diabetic patients and control group according to level of Vitamin B12.

Figure 2. Comparison between diabetic patients without multivitamin replacement and control group according to level of Vitamin B12.

Table 1. Comparison between total diabetic patients and control group according to level of vitamin B12.

Table 2. Comparison between patients with diabetes not receiving multivitamin supplements and control group according to level of Vitamin B12.

Table 3. Distribution of the studied people with diabetes with or without multivitamin replacement according to high vitamin B12 level.

In our study, 0.5% of patients had nephropathy, 1.1% had retinopathy, 6.1% had neuropathy and 65.8% of diabetic patients received metformin treatment. , in current study, 31% of diabetic patients had low hemoglobin levels, however there was no statistically significant relation between B12 deficiency and low hemoglobin, diabetic complications including nephropathy, retinopathy and neuropathy ().

Table 4. Distribution of the studied cases according to the presence of low hemoglobin, diabetic complication and metformin intake (n = 1718).

Table 5. Relation between vitamin B12 and other parameters (n = 1718).

We compared vitamin B12 in diabetic patients with metformin to those not on metformin and we excluded those who are on multivitamins and the results showed that 192 patients (17%) out of 1131 patients on metformin had vitamin B12 deficiency, while 83 patients (14.1%) out of 587 patients not on metformin therapy had vitamin B12 deficiency, therefore there was no statistically significant difference between both groups (, .

4. Discussion

This is a retrospective study designed to study the link between vitamin B12 level and diabetes, metformin therapy. In our study, we identified 12.9% of type 2 diabetic patients with B12 deficiency when defined as a serum B12 level less than 200 pg/ml, most of them (69.8%) were on metformin therapy and 65.1% of the patients with normal vitamin B12 level were on metformin therapy; therefore, there was no difference in percentage of vitamin B12 deficiency versus metformin use.

The prevalence of B12 deficiency in type 2 diabetes individuals taking metformin has been shown to range from 5.8% to 33%. The various study definitions of vitamin B12 insufficiency may be able to account for this wide discrepancy in the prevalence.

A definite low vitamin B12 was defined as blood vitamin B12 concentrations of less than 100 pg/ml in the study by Pflipsenet al. [Citation8] on 203 outpatient diabetic patients at a large primary care clinic in the United States. In the primary care type 2 diabetic group, they discovered a prevalence of metabolically verified B12 insufficiency of 22%. Physicians must take into account the concomitant impact of vitamin B12 deficiency in population prone to neuropathic problems given the frequency of 22%. To fully quantify the clinical consequences of the deficit in these patients, more research is needed.

Adnan Khan et al.’s [Citation20] study included 29.66% type 2 diabetes mellitus individuals in the group who were vitamin B12 deficient. Comparable conclusions have been reached by earlier researchers, however it is still unclear exactly how this impairment is caused.

In our study, diabetic patients were not vitamin B12 deficient and even vitamin B12 is more deficient in the non-diabetic group even after removing those with low vitamin B12. It is challenging to compare the frequency of vitamin B12 deficiency in diabetic patients and general populations because most research utilize different definitions of vitamin B12 deficiency and because cultural and religious views vary greatly around the globe. One population-based study found that 12.1% of 1048 senior Finnish participants, aged 65 to 100, had definite vitamin B12 insufficiency [Citation21]. There is a relatively high frequency of vitamin B12 insufficiency in general Indian population, a nation where a considerable percentage of people practice vegetarianism due to cultural and religious convictions. About 67% of the 441 healthy middle-aged Indian males who participated in Yajnik et al.’s study to assess the prevalence of vitamin B12 insufficiency and hyperhomocysteinemia reported having levels of vitamin B12 that were <150 pmol/L. According to this study’s multivariate analysis, the only significant predictor linked to low vitamin B12 levels was a vegetarian diet [Citation22].

Another study with 175 Indian people aged above 60 years found that 16% of them had vitamin B12 insufficiency, which is indicated by vitamin B12 values below 150 pmol/L [Citation23].

In this study, prevalence of PN in vitamin B12 deficient diabetic group and non-vitamin B12 deficient group was 4.7% and 6.3%, respectively, with no significant association. This is in agreement with Russo and colleagues (2016) [Citation24] who reported that PN was not associated with metformin or B12 deficiency.

In our study 65.8% of diabetic patients received metformin treatment. Patients on metformin treatment seem to be at higher risk of vitamin B12 deficiency [Citation25,Citation26]. Various studies have proved metformin intake with clinical B12 deficiency [Citation27]. In fact, lengthier treatments with metformin at larger doses appear to be risk factors for this deficit. Despite the fact that Matthew C. Pflipsen et colleagues [Citation8] discovered that metformin-using individuals had reduced B12 levels, they did not discover that metformin use was connected to overt B12 insufficiency. Despite an association between high doses of metformin and B12 deficiency, there were no significant metformin dose-dependent correlations.

A large multicenter study was done by Zahid Miyan et al. [Citation28] assessing the link between metformin and B12 deficiency, and its relationship with diabetic neuropathy. In that study, metformin-treated T2DM patients had a considerably higher frequency of B12 insufficiency than did non-metformin users. Contrarily, B12 deficiency was shown to be substantially more common in non-metformin users than in metformin users. It shows that B12 insufficiency was often present in their population and that B12 insufficiency may progress to B12 deficiency when metformin is started in diabetics.

The current study showed no significant relation between vitamin B12 deficiency and multivitamin intake or metformin use. Varied studies have found different frequencies of vitamin B12 deficiency linked to metformin use. In one study by Fakkar et al. [Citation29], there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups when it came to the prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency, which was seen in 4% of the metformin group and 2% of the non-metformin group. According to the United States National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (1999–2006), people with diabetes on metformin had a vitamin B12 deficit at a rate of 5.8% compared to 2.4% of those who were not [Citation30]. Another similar study, which had 351 type 2 diabetes patients, most of whom were receiving metformin treatment, found that 6.60% of patients had vitamin B12 deficiency [Citation31]. While 121 patients with type 2 diabetes treated with metformin were the subject of a South African study, which revealed that 28.1% of the participants were vitamin B12 deficient. The high metformin dosage (2400 mg) and duration (9.6 years) in the participants in comparison to other studies were attributable to this greater frequency [Citation32].

It is believed that metformin-induced B12 deficiency results from vitamin B12 malabsorption, effects on intrinsic factor release. However, the more widely accepted theory is that metformin interferes with the Ca dependent membrane action that is in charge of intrinsic factor absorption of vitamin B12 [Citation18].

Another study in Qatar did not find a link between taking metformin and having low B12 levels or peripheral neuropathy [Citation33]. De Groot and others have demonstrated low prevalence of peripheral neuropathy in people with diabetes taking metformin in comparison to those not taking it [Citation34].

In this study, we searched for particular relationships with B12 insufficiency. We included potential risk factors and protective variables for B12 deficiency in our retrieval investigation. Multivitamins have been shown to increase serum B12 levels, according to published research. Higher serum B12 levels are seen in persons participating in randomized trials who take 6 to 9 µg of B12 daily compared to placebo [Citation35]. In our study, 408 out of 2126 diabetic patients received multivitamin supplements had above the range levels of vitamin b12 exceeding 569 pg/ml. Moreover, diabetic patients who did not receive multivitamin supplementation (n = 1718) had significantly higher level of vitamin B12 comparing to control group and 358 patients (20.8%) had above the range levels of vitamin B12.

In current study, 31% of patients had low hemoglobin levels, however there was no statistically significant relation between B12 deficiency and low hemoglobin, Zahid Miyan et al. [Citation28] showed low hemoglobin in metformin compared with non-metformin group. In previous studies, a significant association between vitamin B12 deficiency and low hemoglobin was noted [Citation36,Citation37].

The study limitations include a number of them. Because it was conducted on a group at a specific center, the results may differ and there may be significant variation from average diabetes patients prevalent in the community. This raised the first question about external validity. Second, this study did not assess the blood levels of methylmalonic acid, which could have improved sensitivity by identifying the vitamin B12 insufficiency at its first, non-symptomatic stage. However, this was an observational study and methymalonic acid is not routinely done or recommended. We could not determine exactly the duration and the dose of metformin, so we excluded that from the data, since metformin use had no significant correlation with vitamin B12 deficiency, the dose and duration might not affect our results.

Our study showed that general diabetic patients should not be routinely given vitamin B supplements, as sometimes happens in the community and as sometimes common belief among some people with diabetes and among some physicians.

People on metformin with signs or symptoms of vit b 12 deficiency, it may be prudent to check the levels and give replacement if necessary. Then we might later check their dietary habits because it might relate to that rather than metformin given the higher prevalence among non diabetics in our population.

Vitamin b12 is a drug and it should not be given without enough evidence for all diabetic patients. The average cost of vitamin b12 supplementation per month is $16–32 therefore we could say that there is a cost reduction of $192–384/year per patient in a 10,000 patients that means a1.9–3.8 million dollars reduction which can be used for the benefit of these patients. The cost of supplementation could be better utilized in better improving diabetes control and its complications. Moreover, its high levels may still cause harm.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ahmed Kamal Swidan

Ahmed Kamal Swidan is an assisstant professor of endocrinology at faculty of medicine, from alexandria, Egypt.

Marwa Ahmed Salah Ahmed

Marwa Ahmed Salah Ahmed is a lecturer of endocrinology at faculty of medicine, from Alexandria, Egypt.

References

- Oh R, Brown D. Vitamin B12 deficiency. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67(5):979–986.

- Tesfaye S, Boulton AJ, Dyck PJ, et al. Diabetic neuropathies: update on definitions, diagnostic criteria, estimation of severity, and treatments. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(10):2285e93. DOI:10.2337/dc10-1303

- Candrilli SD, Davis KL, Kan HJ, et al. Prevalence and the associated burden of illness of symptoms of diabetic peripheral neuropathy and diabetic retinopathy. J Diabetes Complicat. 2007;21(5):306e14. DOI:10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2006.08.002

- Gordois A, Scuffham P, Shearer A, et al. The health care costs of diabetic peripheral neuropathy in the U.S. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(6):1790e5.

- Malouf R, Areosa S. Vitamin B12 for cognition. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD004394

- Bottiglieri T, Laundy M, Crellin R. Homocysteine, folate, methylation, and monoamine metabolism in depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry2000. 2000;69(2):228–232.

- Selhub J, Morris M, Jacques P, et al. Folate–vitamin B-12 interaction in relation to cognitive impairment, anemia, and biochemical indicators of vitamin B-12 deficiency.Am. J Clin Nutr. 2009;89(2):702S–706S.

- Pflipsen M, Oh R, Saguil A, et al. The prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency in patients with type 2 diabetes: a cross sectional. Study J Am Board Fam Med. 2009;22(5):528–534.

- Nervo M, Lubini A, Raimundo F, et al. Vitamin B12 in metformin-treated diabetic patients: a cross-sectional study in Brazil. Revista da Associação Médica Brasileira. 2011;57(1): 56-46-9. doi:10.1590/S0104-42302011000100015.

- Liu K, Dai L, Jean W. Metformin-related vitamin B12 deficiency. Age Ageing. 2006;35(2):200–201.

- Kumthekar A, Gidwani H, Kumthekar A. Metformin associated B12 deficiency. J Assoc Physicians India. 2012;60:58–59.

- Kos E, Liszek M, Emanuele M, et al. Effect of metformin therapy on vitamin D and vitamin B12 levels in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Endocr Pract. 2012;18(2):179–184.

- Reinstatler L, Qi Y, Williamson R, et al. Association of biochemical B12 deficiency with metformin therapy and vitamin B12 supplements. The national health and nutrition examination survey, 1999 –2006. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:327–333.

- Qureshi S, Ainsworth A, Winocour P. Metformin therapy and assessment for vitamin B12 deficiency: is it necessary? Pract Diabetes. 2011;28:302–304.

- U.S Department of Health and Human Services. Clinical laboratory fee schedule 2010. Accessed December 5, 2011.

- Robert C, Langan M, Kimberly J, et al. Update on Vitamin B12 Deficiency. Am Fam Physician. 2011;83(12):1425–1430.

- Mazokopakis E, Starakis I. Recommendations for diagnosis and management of metformin-induced vitamin B12 (Cbl) deficiency. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012;97:359–367.

- Aroda VR, Edelstein SL, Goldberg RB, et al. Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Long-term metformin use and vitamin B12 deficiency in the diabetes prevention program outcomes study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(4):1754–1761.

- Hannibal L, Lysne V, Bjørke-Monsen AL, et al. Biomarkers and algorithms for the diagnosis of vitamin B12 deficiency. Front Mol Biosci. 2016 Jun 27;3:27. doi:10.3389/fmolb.2016.00027.

- Khan A, Shafiq I, Hassan Shah M. Prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency in patients with type ii diabetes mellitus on metformin: a study from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Cureus. 2017 Aug 18;9(8):e1577.

- Loikas S, Koskinen P, Irjala K. Vitamin B12 deficiency in the aged: a population-based study. Age Ageing. 2007;36:177–183.

- Yajnik C, Deshpande S, Lubree H. Vitamin B12 deficiency and hyperhomocysteinemia in rural and urban Indians. JAPI. 2006;54:775–782.

- Shobhaa V, Tareya S, Singh R. Vitamin B₁₂ deficiency & levels of metabolites in an apparently normal urban south Indian elderly population. Indian J Med Res. 2011;134(4):432–439.

- Akinlade KS, Agbebaku SO, Rahamon SK, et al. Vitamin b12 levels in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus on metformin. Ann Ib Postgrad Med. 2015;13(2):79–83.

- Filioussi K, Bonovas S, Katsaros T. Should we screen diabetic patients using biguanides for megaloblastic anaemia? Aust Fam Physician. 2003;32(5):383–384.

- Pongchaidecha M, Srikusalanukul V, Chattananon A, et al. Effect of metformin on plasma homocysteine, vitamin B12 and folic acid: a cross-sectional study in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Med Assoc Thai. 2004;87(7):780–787.

- S E A, Noel E, Goichot B. Metformin-associated vitamin B12 deficiency Arch Intern Med. Arch Internal Med. 2002;162(19):2251–2252.

- Miyan Z, Waris N. Association of vitamin B12 deficiency in people with type 2 diabetes on metformin and without metformin: a multicenter study, Karachi, Pakistan. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2020 May;8(1):e001151.

- Fakkar NFH, Marzouk D, Allam MF, et al. Association between vitamin B12 level and clinical peripheral neuropathy in type 2 diabetic patients on metformin therapy. Egypt J Neurol Psychiatry Neurosurg. 2022;58(1):46. DOI:10.1186/s41983-022-00483-9

- Reinstatler L, Qi YP, Williamson RS, et al. Association of biochemical B12 deficiency with metformin therapy and vitamin B12 supplements: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2006. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(2):327–333.

- Kwape L, Ocampo C, Oyekunle A, et al. Vitamin B12 deficiency in patients with diabetes at a specialised diabetes clinic, Botswana. JEMDSA. 2021;26(3):101–105.

- Ahmed MA, Muntingh G, Rheeder P. Vitamin B12 deficiency in metformin-treated type-2 diabetes patients, prevalence and association with peripheral neuropathy. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2016;17(1):44.

- Spallone V, Morganti R, D’Amato C, et al. Validation of DN4 as a screening tool for neuropathic pain in painful diabetic polyneuropathy. Diabet Med. 2012;29(5):578–585. DOI:10.1111/j.1464-5491.2011.03500.x

- de Groot-Kamphuis DM, van Dijk PR, Groenier KH, et al. Vitamin B12 deficiency and the lack of its consequences in type 2 diabetes patients using metformin. Neth J Med. 2013;71(7):386–390.

- Wolters M, Hermann S, Hahn A. Effect of multivitamin supplementation on the homocysteine and methylmalonic acid blood concentrations in women over the age of 60 years. Eur J Nutr. 2005;44(3):183–192.

- Kwok T, Cheng G, Woo J, et al. Independent effect of vitamin B12 deficiency on hematological status in older Chinese vegetarian women. Am J Hematol. 2002;70(3):186–190. DOI:10.1002/ajh.10134

- Soofi S, Khan GN, Sadiq K, et al. Prevalence and possible factors associated with anaemia, and vitamin B 12 and folate deficiencies in women of reproductive age in Pakistan: analysis of national-level secondary survey data. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e018007