Abstract

The relationship of aesthetics to ethics is explored through a discussion of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Japanese military woodblock prints and recent Daesh (ISIL) media productions. Ruth Benedict’s The Chrysanthemum and the Sword is praised for its anthropological ‘nearness’ to a ‘dangerous’ local aesthetics and ethics, a ‘proximity’ that philosophers of aesthetics seem reluctant to entertain. Thierry de Duve’s engagement with Kant’s sensus communis (which creates the ‘oughtness’ of art) is invoked to help explain why politics is always inextricably aestheticized and aesthetics always intrinsically political.

Most readers will recognize my title as the declaration made by the US Air Cavalry commander played by Robert Duvall in Francis Ford Coppola’s Vietnam war epic Apocalypse Now! His transgressive aesthetic appraisal of the smell of warfare confronts one with the philosopher of art Arthur C. Danto’s suggestion that the ‘mystical chrysanthemums’ caused by high-altitude bombing are not a fit subject for ‘an aesthetic attitude’ (cited by Hanson Citation1998, 205), an issue discussed by the philosopher of aesthetics Hanson (Citation1998) in an article memorably titled ‘How Bad Can Good Art Be?’. This itself seems a distant echo of Walter Benjamin’s sardonic commentary on the Futurist Marinetti’s eulogy to a war that is beautiful because it ‘enriches a flowering meadow with the fiery orchids of machine guns’ (Benjamin Citation2009, 57). The Robert Duvall character reawakens this highly problematic appreciation of the aesthetics of mayhem and murder, one that I will explore in this paper in relation to Japanese woodblock prints celebrating late nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century Imperialist wars.

‘Bad’ aesthetics (and ethics)

Chrysanthemums and war are central to the topic I want to focus on here, namely military aesthetics in Japan and what, anthropologically speaking, it is possible to say about its ethics. However, before we get there I have to mention another matter. This concerns my enthusiasm for the topic and my lack of expertise in it. For 30 years I have worked on Indian popular visual culture, focusing on mass-produced popular devotional and political images and also on the early history of photography as well as current vernacular small-town studio practices.

However, recent visits to Japan have fired an intense enthusiasm for woodblock prints and chromolithographs, especially for those depicting battle scenes (sensō-e) from the first Sino-Japanese War of 1894–95 and the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–05 (Sharf, Morse, and Dobson Citation2005; Virgin Citation2005). The contents of this paper are my first stumbling steps in a new field, and I hope that I make clear my indebtedness to the scholarship of others who have labored long and hard in this area and who possess skills that it will take me decades more to acquire. That this is a newfound interest has consequences: chief among these is that I am ignorant of untranslated Japanese-language sources on these prints and their aesthetics. My intention here is not to provide a historically sensitive contextualization of Japanese print-making of a certain period, but rather through the abrupt confrontation with some ideas from Kant and some observations on contemporary Daesh aesthetics to precipitate questions that would otherwise remain concealed. My method is not intended to be comparative. It is, rather, offered in the spirit of Eisensteinian montage, exploring what happens at the point where very different images and practices collide.

The aesthetic impact of ukiyo-e, images (including woodblock prints – nishiki-e) from the ‘floating world’ of the new capital city of Edo (Tokyo), on European art has been well documented (Put Citation2005). We know that Manet, Degas and Monet were admirers of Japanese woodblock images and that Vincent van Gogh collected over 500 examples (see van Rappard-Boon, van Gulik, and van Bremen-Ito Citation2006) and made copies of two famous Hiroshige prints. These are vivid examples of aesthetic contact zones and of a transculturation which operated in both directions, for Japanese artists were also extensively influenced by Western techniques, this being most apparent perhaps in the so-called Nagasaki-e and then Yokohama-e genres (Chaiklin Citation2005; Merrit and Shigeru Citation2005) which gave form to Japan’s fascination with the new people, commodities and technology that would rapidly transform it from a feudal into a rapidly urbanizing consumer society. Nagasaki-e, inspired by Chinese Buddhist New Year’s prints, offered ‘glimpse[s] of mysterious peoples and worlds from beyond the ocean’ (Chaiklin Citation2005, 225) and were widely diffused throughout Japan. Screech (Citation2002, 217) brilliantly suggests that Nagasaki-e, with their ‘view from on high’, reflected their subject’s status as a place of visual alterity characterized by an ambiguous relation to the ‘normal space of the realm’ and which unleashed ‘a general unbalancing of scale’. Woodblock prints increasingly became a space for commentary on ‘the customs and habits of … Western strangers’ (Merrit and Shigeru Citation2005, 266) following the arrival of Commodore Perry’s ‘Black Ships’ in Tokyo Bay in 1853, through Yokohama-e, a genre of images that vividly traces the fascination with foreigners, their material culture and the dramatic impact their presence was having on the port of Yokohama, which was frequently presented in bird’s-eye view.

After the Meiji Restoration of 1868 and the relocation of the capital from Kyoto to Edo, the stone buildings of Ginza, street scenes with bicycles, and the newly built railways all became popular subjects for woodblock triptychs. Utagawa Kuniteru II’s 1870 triptych () of a street-scene by the Nihonbashi bridge in Tokyo is exemplary in this regard. A metaled road takes up the first two-thirds of the foreground of the image, with a sprawling Edo skyline in the distance locating us at the center of a bustling metropolis. The road is crammed with vehicular traffic and pedestrians: large horse-drawn carriages, small buggies, rickshaws, tricycles, bewildered women, lost children and an excited dog. An extraordinary sense of fissiparous movement in a new urban space is created by the diversity of devices and trajectories, and of identities both local and foreign. We might think of it as woodblock prints’ presaging of what Vertov would achieve in 1929 with film in Man with a Movie Camera: the fusion of a new technics with a new lifeworld and mode of perception.

Japan and India

Japanese aesthetics had been mobilized in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century by a number of key Bengalis as part of their quest for ‘another Asia’ (Bharucha Citation2007), a hinterland of political affiliation that offered an alternative to British aesthetic colonization through government art schools, the teaching of perspectival drawing and the seemingly inexorable rise of European academic oil painting. Figures such as Rabindranath and Gaganendranath Tagore were at first enthused by the wash techniques that seemed to repudiate the insistent materialism of European traditions, but were quickly alienated by the rise of nationalistic militarism (Guha-Thakurta Citation1992; Nandy Citation1994).

My own experience, viewing Japanese material so to speak through the prism of Indian popular material, was that Japanese popular prints were dramatically more topical and immersed in history than anything produced in India. Japanese images seemed to tell a history of transience, of fast-moving political transformations and explosive battles, whereas Indian images seemed to deal more in, if not the ‘eternal’, certainly in the durable, in images that – while not quite static – evolved slowly. Japanese images seemed directed at an audience desperate for sensation, for dramatic new effects of light and form in which the daring of the artist pushed recognition and intelligibility to its limits. Indian audiences by contrast sought familiarity, newness as a kind of pastiche of modulation (‘new but not too new’; Jain Citation2007), and famously rejected experiments that seemed to confound what had already in some sense been seen in advance.

In at least one respect, Japanese and Indian print production was very similar. Under the Tokugawa shogunate (that is, before the Meiji restoration in 1868), all contemporary political commentary was suppressed with cases of ‘house arrest in manacles’ and the destruction of printing block and (unsold)Footnote1 prints (Thompson Citation2005, 318). Consequently, as Morse (Citation2005, 35) argues, ‘Artists had to resort to recasting the narratives of their own time in the historical terms of analogous precedents’. Thompson (Citation2005, 318) notes that current events were ‘depicted in plays, books and prints with false historical settings (most commonly the twelfth or fourteenth centuries)’.Footnote2 Prior to 1868, allegory was the necessary refuge of political commentary; after that date, events such as the Boshin War (1868) and the Seinan War or Satsuma Rebellion (1877) were pictured much more openly and consolidated an image of General Saigō Takamori as a popular tragic hero. In India, legislation such as the 1867 Dramatic Performances Act and the 1910 Press Act drove a fugitive politics to seek the alibi of a colonially authorized ‘religious’ expression (Pinney Citation2009). India’s experience after 1867 would mirror that of Japan before 1868, creating an ‘iatrogenic’ fusion of the political within the religious.

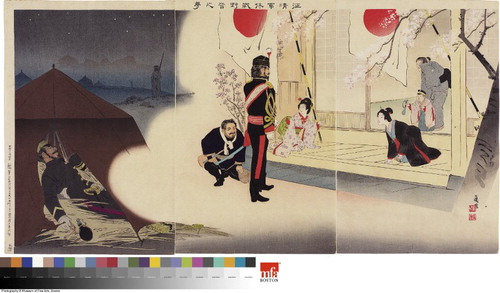

One further dimension which suggests parallels with India is astutely diagnosed by Anne Nishimura Morse. In India, it was crystallized by Tagore’s Home and the World, which described the division between a Europeanized colonial public sphere occupied by Bengali men and the domestic enclave of the home, in which Bengali women maintained a resistant zone of cultural purity (Chatterjee Citation1993; Dirks Citation1993). Morse (Citation2005, 41) notes that in Japan ‘The world of war, with its male protagonists – the domain that engaged with the Western world – was expressed in western visual language’. Wives and mothers by contrast sustained the home front and inhabited a quite different, more conventional visual world. Morse shows how the two worlds are often brilliantly aligned (or rather, disjoined), perhaps most perfectly in Kobayashi Kiyochika’s 1895 triptych A Soldier’s Dream at Camp during a Truce in the Sino-Japanese War (). At bottom left we see a soldier, asleep in his tent, positioned in a modern landscape of war. The central and right-hand ōban panels are occupied by his dream in which he returns to a home flooded by light, flanked by cherry blossom and at the center of which stands his kimono-ed son wearing a military cap and clutching a toy bugle. Morse (Citation2005, 41–42) perceptively notes how the ‘subtly shaded Europeanized features of the foreshortened recumbent soldier contrasts with the women of his household, who are shown with the traditional abbreviated features … ’.

Figure 2. Kobayashi Kiyochika, 1895. A Soldier’s Dream at Camp during a Truce in the Sino-Japanese War (Seiseigun taisen yaei no yume). Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Jean S. and Frederic A. Sharf Collection, 2000.279a–c. Photograph c. 2016 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Kiyochika’s soldier might be seen to reveal the damage done by war, and the fragility of the masculine armature that was progressively generated over successive wars. However, the vast majority of woodblock prints from these early wars serve only to refute Arthur C. Danto’s suggestion that the ‘mystical chrysanthemums’ caused by high-altitude bombing are not a fit subject for ‘an aesthetic attitude’. They celebrate chrysanthemums and cherry blossoms together with exploding shells in a visual language whose perversely ethical claims an anthropology of aesthetics needs to understand.

Ethics, virtue and evil

The (literal) chrysanthemums of course made up one half of the ‘fire and ice’ duality that Ruth Benedict used to characterize Japanese culture in her wartime report The Chrysanthemum and the Sword, commissioned by the US Office of Wartime Information and published in 1946 (Benedict Citation1946). At the heart of the antinomies that Benedict explored was the fact that the Japanese were, as she wrote, ‘both aggressive and unaggressive, both militaristic and aesthetic’ (Citation1946, 2). Benedict’s book has rightly been criticized for its totalizing construct of a culture-wide ideology that should more properly have been located in a particular section of that society and particular period of its history (Lummis Citation2007; Ryang Citation2002), but it has nevertheless been extraordinarily influential in Japan itself (selling two million copies in translation) and has been credited with the development of the entire Nihonjinron (or self-essentializing) discourse on the uniqueness of Japanese identity.

Rereading Benedict, it is easy to see why it became so popular in Japan for it argued a case for understanding the ethical coherence of what to non-Japanese might appear puzzling. She is keen to stress the internal robustness of a cultural ideology that has always, as she writes, ‘been extremely explicit in denying that virtue consists in fighting evil’ (Citation1946, 190). She notes what now we would term the ‘perspectivism’ advanced by the eighteenth-century Shintoist Motoori, who argued for the distinctiveness of Japanese ethics and their moral superiority. The Chinese, by contrast, Motoori argued, had a moral code that raised ‘jen, just and benevolent behavior, to an absolute standard’ (italics added) but this was proof of their inferior nature and the need for an ‘artificial means of restraint’ (Benedict Citation1946, 191).

Reading Benedict (Citation1946, 192) on the American incomprehension of the Japanese stress on ‘sacrificing one’s personal desires and pleasures’ and on ‘the idea that the pursuit of happiness is a serious goal of life is to them an amazing and immoral doctrine’ evokes the Islamist slogan ‘we love death as you love life’.Footnote3 Benedict forces the reader (prefiguring Faisal Devji’s recent work on Al Qaeda’s ‘humanity’, Citation2008) to accept that this is indeed an ethical position, merely one that may differ from that of her readers.

The ‘happy ending’, Benedict writes, is rare in Japanese novels and plays. By contrast ‘American audiences crave solutions. They want to believe that people live happily ever after. They want to know that people are rewarded for their virtue’ (Citation1946, 192). This resonates with Devji’s (Citation2008, 203) observation that ‘the Christian concept of evil is not one that exists in the rhetoric of militancy … its place being taken by the Muslim’s own sin in refusing to sacrifice himself for humanity’. Benedict’s study of Japanese ethics and aesthetics perfectly anticipates, I think, EuroAmerica’s inability to understand the ethics and aesthetics of Islamism, and also reveals how little development there has been in mainstream EuroAmerican approaches to the philosophy of aesthetics.

Exemplary of a position that differs little from the one that Benedict was trying to critique is Mary Deveraux’s consideration of the ‘beauty and evil’ that co-exists in Leni Riefenstahl’s film Triumph of the Will. This documentary about the 1934 Nazi Party Nuremberg Rally, which she suggests is ‘at once masterful and morally repugnant’ (Deveraux Citation1998, 227), was once memorably described by George Steiner as ‘forever carrying the mark of Auschwitz on its brow’,Footnote4 a position with which I cannot disagree. Deveraux (Citation1998, 248) spends an inordinate amount of time discussing how we should respond to the fact that Triumph of the Will ‘renders something that is evil, namely National Socialism, beautiful and, in so doing, tempts us to find attractive what is morally repugnant’. Part of her solution lies in the supposed possibility of separating beauty from politics. Rather incredibly, she thinks we are capable of ‘[a]ppreciating the beauty of this vision (seeing the possible appeal of the idea of a benevolent leader, of a unified community, of a sense of national purpose)’ without also ‘finding the doctrines or the ideals of National Socialism appealing’. Equally implausibly, she proposes that we can be seduced by the ‘concrete vision’ of what is beautiful and at the same time ‘reject’ and be ‘utterly horrified’ by what the Nazis did (1998, 249).

There is what she terms ‘a step’ between these two positions, (‘between finding the film’s concrete artistic vision beautiful and endorsing the doctrines and ideals of National Socialism’) and this step is a moral one which we need not (and, of course should not) take (1998, 249). While of course I agree that we indeed should not take such a step, the idea that in the face of so much supposed beauty we can decide that we ‘need not’ seems utterly fanciful. The aestheticization of politics of all varieties is insidious and powerful and usually doesn’t allow the spectator to stand back and make conscious decisions about which part of the package they want to accept. As de Duve (Citation2015, 153) notes, sensus communis aestheticus ‘is affective and not cognitive in nature’. It doesn’t offer ‘steps’ where we can consider choices. Rather, aesthetics in the cause of bad politics usually produces infatuation and contamination. National Socialism was, as Susan Sontag (Citation1975) has argued, a repertoire of dress codes, gestures, insignia and material crimes (what she calls the aesthetics of the ‘righteousness of violence’). Sontag implies an aesthetics of ‘escalation’ rather than presuming that Nazism offered ‘steps’ between which one could choose.

Deveraux does not even get to Benedict’s starting point, which is the need to understand the powerful effect of an aesthetical/ethical system on those in whom it has been inculcated (rather than those watching it 80 years later on DVD). Deveraux seems to have no grasp of what Benjamin would theorize as the aestheticization of politics, Lyotard’s memorably powerful statement that ‘there is always something happening in the arts that incandesces the very embers of society’ (Carroll Citation1987, 30) and Rancière’s currently fashionable but rather pale Lyotard-lite echo of this insight (Rancière Citation2004).

For Benedict, the chrysanthemum and the sword served as icons of what she termed the ‘dilemma of virtue’ (Citation1946, 195). Her analysis attempts to culturally explain what appeared to her to be extremes of belief and behavior that those she terms ‘Occidentals’ have difficulty in reconciling. She is eager to explain that ‘in Japanese life the contradictions, as they seem to us, are as deeply based in their view of life as our uniformities are in ours’ (Citation1946, 197). Benedict then discusses how Japanese heroic narratives may puzzle the Occidental who expects heroes to ‘choose the better part’ and allow ‘virtue to triumph’ as she puts it. The Japanese hero by contrast tends to ‘settle incompatible debts to the world and to his name by choosing death’ (Citation1946, 199).

The aesthetics of Japanese militarism has come to interest me through the study and collection of popular woodblock images, images that first struck me as powerful because of their extraordinary topicality as compared to Indian printed visual culture of the same period. Japanese print culture, while it has its continuing preoccupations with courtesans, with the 47 Ronin,Footnote5 and with Kabuki characters,Footnote6 was highly responsive to current events, especially to Japan’s military adventures, and in particular the first Sino-Japanese war of 1894–95 and the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–05. Within woodblock print culture enduring tropes coexisted easily with what was essentially a form of pictorial journalismFootnote7 (in this context it is worth noting that Benedict, for all her cultural essentialization, opens her book by thanking her ‘wartime colleague’ Robert Hashima, one of many Japanese-Americans who were ‘placed in a most difficult position’Footnote8 and very strongly stresses the rapid transformation under the MacArthur administration post-VJ Day in 1945).Footnote9

The aestheticization of war

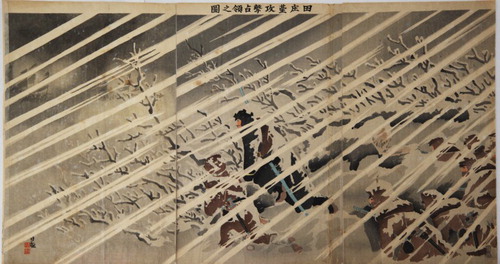

The first Sino-Japanese war of 1894–95 (essentially a clash between Japan and China for control of the Korean peninsula) triggered an outpouring of war triptychs,Footnote10 highly propagandistic, and often imaginary, scenarios in part based on the journalistic accounts of war reporters and of sketch artists at the front, which were the widescreen or IMAX formats of their day.Footnote11 Thousands of different images were produced for an eager public and some were printed in editions of tens of thousands (this, plus the disinclination of contemporary Japanese collectors to buy them, accounts for their surprisingly low prices). Many of them, let us not waste words, depict and eulogize war crimes (the Tokyo publisher Shinbaku’s recent collection of images is appropriately titled Massacres in Manchuria, Hunter Citation2013). In ways that prefigure Marinetti, they celebrate violence and develop an astonishingly innovative visual language for the depiction and celebration of mechanized war. Images often have strong diagonals, and always stage an epic clash. I find the best of these images (and the best artist is Kobayashi Kiyochika, although I have a fondness for the more conventional compositions of Watanabe Nobukazu []) extraordinary. I find myself in thrall to the amazing visual effects and the sheer excitement of an art form that is decades ahead of what would come to seem revolutionary during the second decade of the twentieth century in Europe. In this respect Kiyochika’s Illustration of the Attack and Occupation of Tienchuangtai (), with its diagonal blizzard effects (rendered as embossed hand-applied stripes on the prints), seems to prefigure Edward Wadsworth and other English Vorticists. Kiyochika presents a carefully delineated scene in which the commander of a small group of soldiers peers toward a flag-bearing army distantly glimpsed at the left through the snowy branches of a woodland thicket. But overlaying this whole naturalistic depiction are numerous diagonal white lines, about one-third of an inch wide, conveying a sense of a driving blizzard with enormous success and conscripting this perilous environment, through its strong abstraction, into the harsh machinic world of war.

Figure 3. Kobayashi Kiyochika. c. 1895. Illustration of the Attack and Occupation of Denshodai. Woodblock triptych. 14 × 27 inches. Author’s collection.

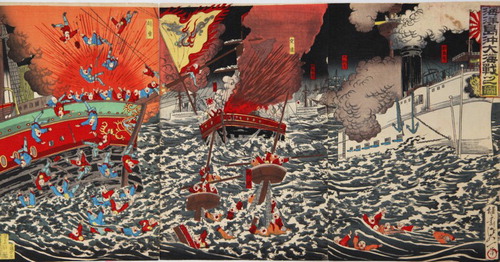

Figure 4. Watanabe Nobukazu. C. 1895. Naval battle during Sino-Japanese War. Woodblock triptych. 14 × 27 inches. Author’s collection.

In the Sino-Japanese war images there is conventional beauty in the way that waves created by (British-built) Japanese destroyers or the sinking of Chinese wooden ships are depicted: these recall Hokusai’s iconic The Great Wave off Kanagawa, the first print in the Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji published in the 1830s. The dark blue bodies of the building waves are decorated with elegant white frondery, transforming water into forms to which musical vocabulary might be applied. The delicate beauty of these waves is complemented by the dramatic vigor of glorious explosions created by bursting shells, seemingly harmlessly in midair but often with lethal consequences for their hapless Chinese victims, which recall (to this viewer, at least) the petals of red chrysanthemums and the rising sun of the Japanese flag. That flag is, intriguingly, nearly always the Imperial Japanese Navy flag (the Kyokujitsu-ki, with kinetic red stripes radiating from a smaller central red sun), almost never the simple red circle of the Nisshōki flag,Footnote12 even in ground engagements. Perhaps that is too sun-like and insufficiently chrysanthemum-like. The Japanese flag oscillates between signifier of national identity and the kinetic energy of an exploding shell, pulsing back and forth in ways that recall Barthes’ (Citation1972) comments on Bataille’s Story of the Eye and the ‘declension’ or ‘vibration’ of its central object.

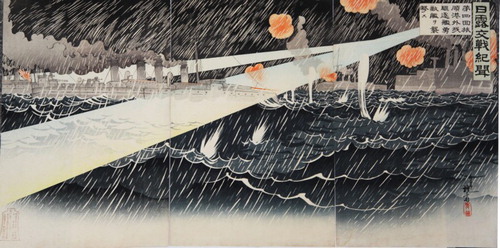

The Russo-Japanese war 10 years later generated, consensus has it, fewer woodblock prints and more chromolithographs and photographs. But there are masterpieces depicting this war, including to my mind some of the greatest of them all: Migita Toshihide’s News of Russo-Japanese Battles: For the Fourth Time Our Destroyers Bravely Attack Enemy Ships Outside the Harbor of Port Arthur (1904) () and what might be formally the most innovative of all, Kiyochika’s Our Torpedo Hits a Russian Warship in the Great Naval Battle of Port Arthur from the same year, depicting a piscine missile striking a Russian vessel before the formal declaration of hostilities (). The print was published one week after this event (Till Citation2008, 116). The image is a homage to submersibility. A brackish green water occupies the front two-thirds of the image, and its focusFootnote13 hovers between the sloshing surface of this torrid sea and an obscene, secret, almost divinely placid, submarine realm in which Japanese stealth punctures Russian bombast. This disjuncture between sky and sea, horizon and underwater is perforated by the lurid orange explosions of naval artillery and the quiet circles of disturbed water left in the trail of the torpedo.

Cherry blossoms and suicide bombers

The iconography established by artists such as Watanabe Nobukazu, Toshihide and Kiyochika was not confined to warmongering woodblock prints. As Lafcadio Hearn (cited in Morse Citation2005, 32) documented in 1904, it spilled out into every aspect of Japanese life: ‘Even silk dresses for baby girls had charming ornamentation composed entirely of war pictures … blended into one astonishing combination: naval battles, burning warships, submarine mines exploding; torpedo boats attacking … colours of blood and fire … ’. Many later examples of what Dower (Citation2012, 46) terms an ‘intense socialization for war’ are illustrated in Atkins (Citation2012).

This fusion of a militarized aesthetics with conventional symbols of beauty has a deeper and more profound history, one that has been superbly documented by Ohnuki-Tierney (Citation2002). She has shown how, from the beginning of the Meiji period, cherry blossoms became ‘the master trope of Japan’s imperial nationalism’ (Citation2002, 3), a trope that thoroughly seduced the student soldiers who sought ‘the aesthetics of truth and life’ (Citation2002, 4) and who would make up the tokkotai or ‘Special Attack Force’ of whom the cherry blossom-adorned kamikaze pilots are the best known.Footnote14 The issue with which Ohnuki-Tierney grapples is

how complex and interpenetrated meanings, all embodied in the symbol of cherry blossoms with various degrees of physicality – various degrees of blooming and falling – became consolidated into ‘falling cherry petals as young soldiers’ sacrifice for the emperor’ during Japan’s modern period (Citation2002, 9, also 283).

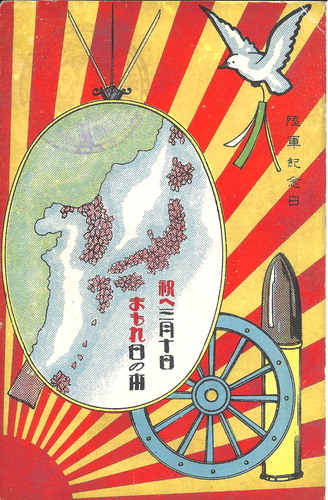

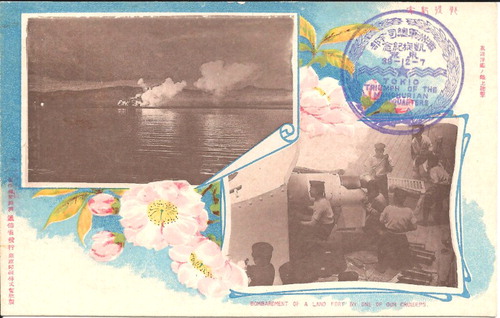

The issue is how ‘aestheticization … leads us to participate in evil operations’ (Citation2002, 23). She notes how cherry trees were planted through Japan’s imperial colonies ( and ), their blossoms symbolizing Japanese souls, as also at the Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo, which became the national site of military memorialization and celebration (Citation2002, 10). Cherry blossom came to embody ‘the idea of sacrifice as a noble and beautiful act’ (Citation2002, 5).

Figure 7. Postcard showing the Korean Peninsula and Japan covered in cherry blossom. c.1905. Author’s collection.

Figure 8. Postcard commemorating the Russo-Japanese War, showing the ‘Bombardment of a Land Fort by One of Our Cruisers’ and cherry blossom. Author’s collection.

This Japanese evidence suggests that, despite initial appearances, there is no contradiction between Wallace Stevens’ claim that ‘Death is the mother of beauty’ (in his poem ‘Sunday Morning’, 1915) and Joseph Brodsky’s claim (in his Nobel Prize Lecture in 1987) that ‘aesthetics is the mother of ethics’. Surprisingly, it turns out that this is what Kant was saying all along – at least, according to Thierry de Duve (Citation2008). In a brilliant exegesis, he shows how Kant’s utopian sensus communis is concerned with the universal claims (the ‘ought-ness’ of art) of an aesthetics to a humankind that he concedes will never agree on what is beautiful.

In explaining this, de Duve (Citation2008, 140) fortuitously discuses a Ms. A. who when confronted with a rose says ‘Oh, what a beautiful rose’ and a Mr. B. who says, conversely, ‘Oh, what an ugly rose’. Obviously, it makes more sense for our purposes here if we imagine them talking about chrysanthemums or cherry blossom. De Duve suggests that Kant might, as it happens, agree with Ms. A; but, surprisingly, concludes that they are both right in claiming an objective validity for the opposing judgments because (and I quote de Duve) the claim ‘imputes to the other the same feeling of pleasure (or pain) that one feels in oneself’ (Citation2008, 141). Their positions are opposed, yet they both agree in making a universal claim ‘you ought to feel the way I feel. You ought to agree with me’ (Citation2008, 141). De Duve (Citation2008, 141) concludes that saying both Ms. A and Mr. B are right ‘is to say that his call on each other’s capacity for agreeing by dint of feeling is legitimate’. In this regard, de Duve persuasively argues, Kant ‘understood [this question] better than anyone before or anyone since’ (Citation2008, 141).

De Duve extracts from this some key principles. Firstly ‘every pure judgment of taste contains an ought, addressed to someone’ and it is this that differentiates such judgments from the merely ‘agreeable’, which are a matter purely of personal preference. Aesthetic judgments by contrast imply a universal address (‘This is a beautiful rose’, not ‘I happen to think this is a beautiful rose’). Secondly, ‘a true or pure aesthetic judgment is a call for agreement by dint of feeling involuntarily addressed to all’ (Citation2008, 141, italics removed) and this holds equally true or Ms. A. and Mr. B. Kant’s sensus communis, de Duve continues, attempts to describe a common sentiment, a ‘shared or sharable feeling … a common ability for having feelings in common. A communality or communicability of sentiment, implying a definition of humankind as a community united by a universally shared ability for shared feelings’ (Citation2008, 141).

A conventional history would at this point say that this is where Kantian ‘anthropology’ fails, since it assumes the possibility or actuality of a universal human culture and – as his pupils such as Herder would very quickly demonstrate – there are many different human cultures whose aesthetics and ethics are incommensurable. De Duve suggests that Kant himself conceded this, recognizing that ‘you ought to feel the way I do’ implies a universal potential, although in practice ‘there is not a hope in the world for universal agreement among us’ (Citation2008, 142). Here, de Duve quotes Kant at length:

Whether there is in fact such a common sense, as a constitutive principle of the possibility of experience, or whether a higher principle of reason makes it only into a regulative principle for producing in us a common sense for higher purposes, whether, therefore, taste is an original and natural faculty or only the idea of an artificial one yet to be acquired, so that a judgement of taste with its assumption of a universal assent in fact is only a requirement of reason for producing such agreement of sentiment; whether the ought, i.e. the objective necessity of the confluence of the feeling of any one man with that of every other, only signifies the possibility of arriving at this agreement, and the judgment of taste only affords us an example of the application of this principle – these are questions we have neither the wish nor the power to investigate as yet. (Critique of Aesthetic Judgment, cited by de Duve Citation2008, 142–43)

What both Kant and de Man identify is the simultaneous desire for the universal (the transcendent – de Duve Citation2015) and the difficulty of universal agreement, a conclusion that all anthropology has subsequently confirmed.Footnote15 They both help us to understand how we can reconcile the claims that ‘aesthetics is the mother of ethics’ and also how, very often, ‘Death is the mother of beauty’.

Kant’s achievement, for de Duve (Citation2008, 143), is that he ‘fathomed the depth of aesthetic disagreements among humans: they amount to nothing less than denying the other his or her humanity’. Kant, de Duve concludes, ‘grasped that an issue of such magnitude – are we capable of living in peace? – was at stake in a sentence so anodyne as “this rose is beautiful”’. De Duve (Citation2008, 144) suggests that we can substitute ‘art’ for ‘rose’. I suggest that we substitute ‘chrysanthemum’ or ‘cherry blossom’ instead.

Islamic State and the aesthetics of violence

Daesh (aka ISIL or Islamic State) are perhaps today’s successors to early twentieth-century Japanese woodblock print artists, world leaders in indelible image trails and the transculturation of images, and I will consider some of their productions in the light of the above history and philosophical positions. Their images occupy a position between fixed identities, establishing a contact zone, because they are all essentially acts of communication with an outside world. They force us to recall de Duve’s Kantian maxim that ‘every pure judgment of taste contains an ought, addressed to someone’.

It may well be that there is image production intended for the consolidation of an internal sensus communis of which we are not aware (although some evidence suggests that within Syria, they finely tune their dictates according to the degree of consolidation of on-the-ground power), but those images that are visible to us are addressed to us. They appear to have two modalities that are not exclusive. Some assume that we might be potential members of the Daesh sensus communis and aim to attract us with their revisioning of their cause as a non-virtual incarnation of Grand Theft Auto, a more exulted version of James Bond, or Disney (these all being highly visible sources for Daesh’s image output). Here the mode of address is perhaps not unlike that of Ms. A and Mr. B: the universal claim is that that you ought not to be sitting at home playing a computer game when you could be shooting actual infidels in their cars, and that martyrdom matters more than whether your cocktail is shaken or stirred.

But Daesh’s most powerful imagery, produced with the same professionalism and knowingness, seems to mobilize a quite different set of communicative expectations predicated precisely on the absence, and indeed impossibility, of a sensus communis. Consider the various execution videos, of individual journalists and aid workers despatched by the so-called Jihadi John, or the mass execution of Coptic Christians on the Egyptian shoreline. These grotesque but carefully choreographed performances seem designed to elicit a form of incommensuration, a horror whose only reflex response would be the violent retribution that they are intended to elicit. To recall the 7/7 bombers, their message seems to be not only that ‘we love death more than you love life’ but also that ‘you will never understand us’, indeed ‘you lack the ability to understand us’. The execution videos might be thought of as an Islamist echo of what in a Japanese context, as we have seen, is called Nihonjinron, that reverse-Orientalism that insists on the inaccessibility of a self to others. This insistence on inscrutability establishes the conditions of self-exclusion, the grounds for a new sensus territorialis, where cherry blossoms and blood are equally beautiful. But in the end, we would have to ask whether there can ever be any truly abject otherness that is not (already) a culturally arranged experience, i.e. that is already anticipated by the system of which alterity is an element. Daesh’s anticipation of incommensuration (of refusal and abhorrence) does not come from some impossible ‘outside’. It is on the contrary born from an intimate knowledge of the boundaries of an aesthetical and ethical system whose limits it understands very well. We would do well to remember the important role that Ruth Benedict’s work played in constructing postwar Japanese discourses of Nihonjinron. In a similar way, we would also need to acknowledge that Daesh’s abjection, its insistence on bringing what we might feel should remain forever ob-scene (off-stage) in front of a global spotlight, demonstrates its cynically clear-headed understanding and manipulation of the system it professes to despise. At the precise moment that it declares its exceptionalism and its indifference to the suffering of the kaffar/kafir, it paradoxically reaffirms what de Duve (Citation2008, 141) described as that ‘shared or sharable feeling … a common ability for having feelings in common. A communality or communicability of sentiment, implying a definition of humankind as a community united by a universally shared ability for shared feelings’. Daesh understand what it is they are transgressing. Were it not for this shared feeling, Daesh’s media strategy – its ‘art’ – would make no sense.

Acknowledgements

I’m grateful to two very knowledgeable reviewers for their extremely thorough critiques of this article.

Notes on contributor

Christopher Pinney is Professor of Anthropology and Visual Culture at University College London.

Notes

1. According to Thompson (Citation2005, 318), there was no effort to recall sold copies of contentious images; hence, the archival record is rich.

2. Thompson (Citation2005, 318) notes that ‘the public learned of the real events through illegal crudely printed broadsheets (kawaraban) and semi-legal handwritten accounts (jitsuroku)’.

3. This was a phrase used in the ‘martyrdom’ videos recorded by Shehzad Tanweer (Devji Citation2008, 201) and Mohammed Siddique Khan, one of the London 7/7 bombers (Pantucci Citation2015) and repeated in 2007, two years before he killed 13 service-people at Fort Hood, Texas, by Nidal Malik Hasan.

4. A comment in a television documentary, whose identity is long forgotten.

5. Benedict (1946, 199) suggests that the story of the 47 Ronin is the ‘true national epic of Japan’ (‘not a tale that rates high in the world’s literature but the hold it has on the Japanese is incomparable’).

6. The tenacity of all these tropes is in large part a result of the strict censorship policies of pre-Meiji regimes (see Thompson 2005).

7. Albeit one that played rather loosely with its sources (cf. the recycling of Sino-Japanese imagery into the later Russo-Japanese imagery [https://ocw.mit.edu/ans7870/21f/21f.027/throwing_off_asia_02/toa_essay02.html] and also the Sudan image, Morse 2005, 43). Morse shows how images from Western colonial wars – such as an 1885 image from the Battle of Kerbekan in Sudan – served as prototypes for the visualisation of later Japanese battles.

8. Benedict (1946, acknowledgements, n.p.) notes that Hashima was ‘interned in a War Relocation Camp, and I met him when he came to Washington to work in the war agencies of the United States’.

9. This is the subject of her final chapter, where she attempts to reconcile dramatic transformation with her strong model of culture: ‘The Japanese have an ethic of alternatives. They tried to achieve their “proper place” in the war, and they lost. That course, now, they can discard, because their whole training has conditioned them to possible changes of direction’ (1946, 304).

10. The dimensions of triptychs, composed of three single ōban sheets, are usually in the region of 29 × 14 inches.

11. A famous 1894 triptych by Mizuno Toshikata, Ban-Banzai for the Great Japanese Empire! Illustration of the Assault on Songhwan: A Great Victory for Our Troops depicts a group of journalists and war artists (including the Kyoto painter Kubota Beisen [Hunter 2013, 29]) on the battle front (Virgin, ed. Citation2001, fig. 26, p. 71).

12. The Nisshōki (‘sun-mark’) or Hinomaru flag has a red circle on a white background and has been the de facto national flag since 1870. It was legally designated the national flag in 1999. The Kyokujitsu-ki has a deep history, having been used (in modified form) as a family crest, an auspicious ‘good catch flag’ by fishermen, and then the naval ensign of the Japanese Navy. I’m grateful to an anonymous referee for clarifying this.

13. The image creates something akin to an auditory focus, for it invites you to hear the distant blasting of shipboard artillery and juxtapose it with the subdued whir of the torpedo. Our ear/eye moves back and forth across this threshold.

14. Kamikaze pilots flew planes with adorned with cherry blossom images and were frequently waved off with cherry branches (Ohnuki-Tierney 2002, 3).

15. The irrelevance of the empirical to the transcendental is key to de Duve’s argument: ‘Postulates cannot be demonstrated. Nothing in the empirical world will ever prove their truth or their falseness’ (2015, 155), Further, ‘transcendental ideas are merely ideas, yet necessary and mandatory ones’ (156).

References

- Atkins, Jacqueline M. 2012. “Wearing Novelty.” In The Brittle Decade: Visualizing Japan in the 1930s, edited by John W. Dower, Anna Nishimura Morse, Jacqueline M. Atkins and Frederic A. Sharf, 91–143. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts.

- Barthes, Roland. 1972. “The Metaphor of the Eye.” In Critical Essays, translated by Richard Howard, 239–247. Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

- Benedict, Ruth. 1946. The Chrysanthemum and the Sword: Patterns of Japanese Culture. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Benjamin, Walter. 2009. “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” In One-way Street and Other Writings, translated by J. A. Underwood, 228–259. London: Penguin Books.

- Bharucha, Rustom. 2007. Another Asia: Rabindranath Tagore and Okakura Tenshin. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- Carroll, David. 1987. Paraesthetics: Foucault, Lyotard, Derrida. New York: Methuen.

- Chaiklin, Martha. 2005. “Nagasaki-e.” In The Hoeti Encyclopedia of Japanese Woodblock Prints, edited by Amy Reigle Newland, 225–228. Amsterdam: Hotei Publishing.

- Chatterjee, Partha. 1993. Nationalist Thought and the Colonial World: A Derivative Discourse. Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- de Duve, Thierry. 2008. “Do Artists Speak on Behalf of All of Us?” In The Life and Death of Images, edited by Diarmid Costello and Dominic Willsdon, 139–156. London: Tate Publishing.

- de Duve, Thierry. 2015. “Aesthetics as the Transcendental Ground of Democracy.” Critical Inquiry 42 (Autumn): 149–165. doi: 10.1086/682999

- Deveraux, Mary. 1998. “Beauty and Evil: The Case of Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will.” In Aesthetics and Ethics: Essays at the Intersection, edited by Jerrold Levinson, 227–255. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Devji, Faisal. 2008. The Terrorist in Search of Humanity: Militant Islam and Global Politics. London: Hurst.

- Dirks, Nicholas B. 1993. “The Home and the World: The Invention of Modernity in Colonial India.” Visual Anthropology Review 9: 19–31. doi: 10.1525/var.1993.9.2.19

- Dower, John W. 2012. “Modernity and Militarism.” In The Brittle Decade: Visualizing Japan in the 1930s, edited by John W. Dower, Anna Nishimura Morse, Jacqueline M. Atkins and Frederic A. Sharf, 9–49. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts.

- Guha-Thakurta, Tapati. 1992. The Making of a New ‘Indian Art’: Artists, Aesthetics and Nationalism c. 1850–1920. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hanson, Karen. 1998. “How Bad Can Good Art Be?” In Aesthetics and Ethics: Essays at the Intersection, edited by Jerrold Levinson, 204–226. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hunter, Jack. 2013. Massacres in Manchuria: Sino-Japanese War Prints 1894–1895. Tokyo: Ukiyo-E Master Series, Shinbaku.

- Jain, Kajri. 2007. Gods in the Bazaar: The Economies of Indian Calendar Art. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Lummis, C. Douglas. 2007. “Ruth Benedict’s Obituary for Japanese Culture.” Japan Focus: The Asia Pacific Journal 5 (7). http://apjjf.org/-C.-Douglas-Lummis/2474/article.html.

- Merrit, Helene and Oikawa Shigeru. 2005. “Yokohama-e”. In The Hoeti Encyclopedia of Japanese Woodblock Prints, edited by Amy Reigle Newland, 266–268. Amsterdam: Hotei Publishing.

- Morse, Anne Nishimura. 2005. “Exploiting a New Visuality: The Origins of Russo-Japanese War Imagery.” In A Much Recorded War: The Russo-Japanese War in History and Imagery, edited by Frederic A. Sharf, Anne Nishimura Morse, and Sebastian Dobson, 32–51. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts.

- Nandy, Ashis. 1994. The Illegitimacy of Nationalism: Rabindranath Tagore and the Politics of the Self. Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- Norris, Christopher. 1988. Paul de Man: Deconstruction and the Critique of Aesthetic Ideology. New York: Routledge.

- Ohnuki-Tierney, Emiko. 2002. Kamikaze, Cherry Blossoms, and Nationalisms: The Militarization of Aesthetics in Japanese History. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Pantucci, Raffaello. 2015. We Love Death as you Love Life: Britain's Suburban Terrorists. London: Hurst.

- Pinney, Christopher. 2009. “Iatrogenic Religion and Culture.” In Censorship in South Asia: Cultural Regulation from Sedition to Seduction, edited by Raminder Kaur and William Mazzarella, 29–62. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- Put, Max. 2005. “Japanese Prints in Europe, 1860–1930.” In The Hoeti Encyclopedia of Japanese Woodblock Prints, edited by Amy Reigle Newland, 387–398. Amsterdam: Hotei Publishing.

- Rancière, Jacques. 2004. The Politics of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible. Translated by Gabrield Rockhill. London: Continuum.

- Ryang, Sonia. 2002. “Chrysanthemum’s Strange Life: Ruth Benedict in Postwar Japan.” Asian Anthropology 1: 87–116. doi: 10.1080/1683478X.2002.10552522

- Screech, Timon. 2002. The Lens within the Heart: The Western Scientific Gaze and Popular Imagery in Later Edo Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

- Sharf, Frederic A., Anne Nishimura Morse, and Sebastian Dobson, eds. 2005. A Much Recorded War: The Russo-Japanese War in History and Imagery. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts.

- Sontag, Susan. 1975. Fascinating Fascism. New York Review of Books. 6 Feb. http://www.nybooks.com/articles/1975/02/06/fascinating-fascism/

- Thompson, Sarah E. 2005. “Censorship and Ukiyo-e Prints.” In The Hotei Encyclopedia of Japanese Woodblock Prints, edited by Amy Reigle Newland, 318–322. Amsterdam: Hotei Publishing.

- Till, Barry. 2008. Japan Awakens: Woodblock Prints of the Meiji Period (1868–1912). Petaluma: Pomegranate Communications.

- van Rappard-Boon, Charlotte, Willem van Gulik, and Keiko van Bremen-Ito. 2006. Collection of Japanese Prints in the Van Gogh Museum’s Collection. Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum/Zwolle.

- Virgin, Louise E., ed. 2001. Japan at the Dawn of the Modern Age: Woodblock Prints from the Meiji Era, 1868–1912. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts.

- Virgin, Louise. 2005. “Woodblock Prints as a Medium of Reportage: The Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese Wars.” In The Hotei Encyclopedia of Japanese Woodblock Prints, edited by Amy Reigle Newland, 273–276. Amsterdam: Hotei Publishing.