ABSTRACT

In this article, I examine the image of child soldiers as depicted in Michel Chikwanine, Jessica Dee Humphreys, and Claudia Dávila’s Child Soldier: When Boys and Girls Are Used in War and Matteo Casali and Kristian Donaldson’s 99 Days and the choice to narrate war and genocide through the filter of young protagonists. Investigating the postcolonial approach adopted in each of these graphic narratives, I am interested in the imagery of postcolonial spaces that, I argue, is conveyed in these graphic novels as essentially savage and dangerous places, promoting colonial stereotypes, as well as in the function of the U.S. and Canada as places of salvation and safety, largely in contrast to war-torn Rwanda and Congo. I regard 99 Days and Child Soldier as powerful tools through which to communicate the problem of child soldiers to the Western world, and examine the suitability of the graphic novel as a medium in this respect.

Images of children participating in war frequently appear on page and screen. Graphic novels, including such recent examples as 99 Days by Matteo Casali and Kristian Donaldson (Citation2011), and Child Soldier: When Boys and Girls Are Used in War, by Jessica Dee Humphreys, Michel Chikwanine, and Claudia Dávila, successfully convey the visual and verbal aesthetics of being a child soldier. Focusing exclusively on these two graphic texts, I explore several issues. First, I examine the image of child soldiers as depicted in the two novels and the choice to narrate war and genocide through the filter of these young protagonists. Second, the postcolonial setting in each of these novels – Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo, respectively – intermingles with two Western countries, the United States and Canada, the nations where the main characters, having survived their wars, ultimately move to. Investigating the postcolonial approach adopted in each of these graphic narratives, I am interested in the imagery of postcolonial spaces that, I argue, is conveyed in these graphic novels as essentially savage and dangerous places, promoting colonial stereotypes, as well as in the function of the U.S. and Canada as places of salvation and safety, largely in contrast to war-torn Rwanda and Congo. Finally, I regard 99 Days and Child Soldier as powerful tools through which to communicate the problem of child soldiers to the Western world, and I examine the suitability of the graphic novel as a medium in this respect.

These graphic novels are indeed conspicuous because of the strong political and ethical implications at their core, for they raise a vexing problem: children, in specific African countries, have been forced into service as soldiers. Despite their African (sub)plots, however, both novels are implicitly connected to North America. Child Soldier was written after the author (who participated in the war in Congo as a child) had moved to Canada; he was asked to write a book that might raise awareness about the existence of child soldiers throughout the world (and on the African continent in particular). For its part, 99 Days narrates the story of a Rwandan boy who was forced to murder his friend during the Rwandan genocide. The boy, later adopted by an African American family, grew up to become a police detective in Los Angeles. The focus on children in these texts and on the atrocities that they witnessed and/or committed raise a number of questions related to war ethics. Here in this article, I examine the problem of war atrocities in the two graphic novels as a tool through which the issue of child soldiers is conveyed most effectively. I also pay attention to the way the foregrounding of atrocity helps distort the images of postcolonial spaces, perpetuating colonialist stereotypes that frame African countries as barbaric spaces. Additionally, through the complex geographies introduced in the graphic novels, I explore the transatlantic connection and geographical entanglement between postcolonial spaces and the West, which ultimately challenges the racialised colonial imaginary.

War experiences and childhood

The image of a child as a helpless, innocent, and generally physically and psychologically weaker being than an adult makes it almost impossible to imagine a child taking part in war. Yet children have often participated in and contributed to various military events throughout history. Even when they have no direct role to play in military actions, children who live in war-torn countries experience war on a daily basis, and thus, involuntarily, they become involved in conflict. Yet while we should certainly take seriously the effects of war on civilian children – as witnesses, casualties, or survivors – the cases when children are forced to participate in war and are thus turned into soldiers are dramatically different. The making of children into soldiers presents a complex ethical issue, for it challenges our conception of childhood, questions the power of the state, and concerns serious political, social, economic, and cultural principles. This changing image of a child soldier, which David M. Rosen formulates via the question, ‘How did the heroic child soldier of an earlier era come to be replaced by the abused and exploited child who is both killer and victim?’ (Rosen Citation2015, 103), is what I investigate in my discussion of 99 Days and Child Soldier.

In earlier epochs, above all the era of Romanticism, children were equated ‘with innocence, imagination and the more benign aspects of the natural world’ (Shail Citation2014, 259), creating rather solid perceptions of what it means to be a child for a very long time. Today, however, such an understanding of children and childhood can be viewed as more stereotypical than realistic. While corresponding to some extent with experience, this definition is obviously no longer the primary way but rather only one of the many ways to imagine children and childhood. This development, in turn, acknowledges that the child should be recognised not as a subordinate being but rather as a person of its own, with social and cultural needs, specific characteristics, and rights, just like those that adults lay claim to. Still, certain areas are generally recognised as ‘adult areas,’ and in such contexts, the involvement of children is an uneasy, delicate, problematic, and even illegal issue. War is definitely one such realm.

It is somewhat problematic to compare war’s effects on children with its impact on adults, simply because, in my view, the experiences of each group differ markedly. Roos Haer claims that ‘[w]ar … entail[s] particularly grave consequences for children in terms of survival, development and well-being’ and foregrounds the transformation of children’s role in war: no longer only ‘passive victims of conflict between armed groups,’ children ‘assum[e] both ancillary and more active combat roles’ (Haer Citation2019, 74). Shielding children from war in conflict zones is an impossible task, just as it is impossible to prevent children living in peaceful territories to find out about war. Yet the involvement of children in war and the possibility that they will experience its trauma can be understood particularly effectively if we define trauma to be ‘neither an exceptional experience nor the rule of experience, but, rather, a possibility of experience’ (Caruth qtd. in Hirsch Citation2004, 9). One can thus argue that war trauma is not exclusively confined to adults; it can and, indeed as history reveals, has happened to children. That their war trauma stimulates somewhat special attention reveals that children’s participation in war, be it direct or indirect, manifests the ‘conflict between childhood and the adult world’ (Kozlovsky Golan Citation2011, 54). War stories told by children as well as cultural texts narrated from a child’s perspective make important contributions to the history of war in general and uncover specific features of particular conflicts. For example, scholars identify ‘children’s perspectives on the Holocaust’ as ‘precious’ (Mihăilescu Citation2014, 73) because they talk about the Holocaust as a form of war waged not just against adults but also against children. At the same time, also in the context of the Holocaust, child protagonists make the cultural narratives that contain them ‘morally embellished,’ intensifying the brutality and atrocity of war through their vulnerability, thus perhaps commenting on war as a deadly event even more powerfully than stories centred on adult protagonists (Prorokova Citation2018c, 380).

Child soldiers constitute a specific group of child participants in war. In this article, when referring to child soldiers I mean only those children who have been forced to fight. Therefore, I do not perceive child soldiers to be heroic military individuals, which would romanticise their participation in conflict. Rather, I consider them to be victims, and those who force them to take up arms are nothing less than criminals. Today, 250,000–300,000 individuals under the age of 18 are involved in war (Rosen Citation2015, 134). Indeed, P. W. Singer argues that ‘[t]he use of child soldiers is far more widespread than the scant attention it typically receives’ (Citation2006, 6). Some of the consequences of participation in war for these children include traumatisation, disability, dislocation, and loneliness (5–6). Importantly, from a humanitarian perspective, these children are seen as victims, a perception that, in turn, has sweepingly transformed the cultural portrayal of child soldiers, including on the pages of graphic novels. Rosen argues: ‘Humanitarian rhetoric seems to have seeped into and reshaped the literary images of child soldiers, upending many of the images of children under arms that pervaded nineteenth- and twentieth-century literature’ (Citation2015, 102). Involving children in war as soldiers is a crime, for ‘international law prohibits the recruitment and use of under-18s by nonstate armed groups, and criminalises the recruitment of use of under-15s by state and nonstate forces alike’ (Kearney Citation2010, 68). But illegal recruitment continues unabated, and the number of children involved in military action is considerable. Most child soldiers forcibly compelled into service are ‘in search of physical protection, access to food and shelter, and the possibility of taking revenge against those who had killed their relatives and destroyed their communities’ (Alcinda Honwana qtd. in Kearney Citation2010, 72). Since ‘[b]oth the “child rights regime,” and the humanitarian moral order affirm the vulnerability of children,’ the interventions made to protect children, including child soldiers, receive widespread international support and approval (Bodineau Citation2014, 114).

Child soldiers as a phenomenon not only reflect the amorality of war and the most duplicitous ways of conducting it; their existence also profoundly challenges our notions of childhood and can be seen as a symptom of the racial and ethnic inequality faced by children from less developed, postcolonial countries, at a time when humanitarianism seems to be a key prerogative of the Western world. Jimmie Briggs (Citation2005) opens his book Innocents Lost: When Child Soldiers Go to War with a description of a photograph of a Liberian child soldier featured in the New York Times: ‘More chilling than the weapon he held was what he wore on his back: a pink teddy-bear backpack, a telling symbol of his lost youth’ (xi–xii). Briggs’ example acutely foregrounds the contradictions embodied by the child soldier, at once an innocent child, a fearless fighter, a dangerous enemy to some, and a pawn controlled by criminals. Yet the image also adds a racial connotation to the child soldier: here we are presented with a black child soldier, overtly signifying that this story comes to us from a postcolonial African country, thus constructing the meaning of child soldiers as a ‘problem’ exclusive to postcolonial spaces that are inherently unstable and dangerous. Granted, out of the 23 countries where illegal recruitment takes place, 10 are in Africa (Kearney Citation2010, 68). To acknowledge this reality is one thing, but, as I further demonstrate, child soldiers have become almost synonymous with Africa (often ‘Africa’ as opposed to specific African countries), a perception which distorts the nature of the problem and profoundly belittles its significance.

Child soldiers as an ‘African problem’

Donna Sharkey (Citation2012) writes: ‘A general sense of the lives of child soldiers exists for most people in the West through ideas such as these: young children who have been abducted, children who have killed their parents, children who have been tortured, girls who have been raped, eight-year-olds who have been used as mine sweeps, and those who have gotten out of control because of drugs, gun powder, and alcohol. This understanding exists in part through photographs depicting these children, transmitting emotions, and anticipating an affective response in us, the viewers’ (262). What I would add here is the observation that these images are also defined through the (post)colonial lens, since many such images – photographs, but also literary and cinematic images – are of child soldiers from African countries. Rosen describes the problem as follows:

Portraits of war as a criminal enterprise began to emerge more fully in contemporary literature and are especially prominent in literature that focuses on African conflicts. While children have been recruited as child soldiers in wars all over the world – Columbia, Kurdistan, Laos, Mexico, New Guinea, Pakistan, Palestine, Peru, the Philippines, Sri Lanka, and New Guinea come immediately to mind – the contemporary literary gaze remains firmly fixed on Africa. Exactly why is unclear. Certainly some contemporary examples of the use of child soldiers in Africa, such as the Revolutionary United Front in Sierra Leone and the Lord’s Resistance Army in Uganda, have provided chilling examples of the abuse of children. But these extraordinary cases have also come to serve as the archetype of children’s experiences in both Africa and elsewhere. Literary treatments of African children at war, almost all geared to Western audiences, magnify this perspective by the lingering tendency to see Africa with Conradian eyes, seeing only the heart of darkness. In fact the general Western discourse about war in Africa, whether precolonial, colonial, or postcolonial, has remained remarkably consistent since the middle of the nineteenth century. In this discourse, warfare in Africa – in contrast to that in the West – is invariably cast as irrational, meaningless, and criminal. (Citation2015, 104-05)

As Rosen aptly points out, the core of the problem is racially and colonially defined. Child soldiers, as stated, are recruited in 23 countries, yet Africa – which continues to bear a colonial stereotype as an undifferentiated space rather than a continent consisting of many distinct countries – is used as an example of poverty and chaos, a conception easily grasped by Western audiences since it extends a vision perpetuated during colonial times into the present, when, in certain contexts, it still functions effectively.

There is a large number of recent novels, biographies, autobiographies, and memoirs written by and/or about former child soldiers from the African continent. Dave Eggers’ novel based on a true story What is the What (2007), Ishmael Beah’s memoir A Long Way Gone: Memoirs of a Boy Soldier (2008), Grace Akallo’s memoir Girl Soldier: A Story of Hope for Northern Uganda’s Children co-authored with Faith J. H. McDonnell (2007), Benjamin Ajak, Benson Deng, and Alephonsion Deng’s memoir They Poured Fire on Us from the Sky: The True Story of Three Lost Boys from Sudan (2015) co-authored with Judy A. Bernstein, Emmanuel Jal’s memoir War Child: A Child Soldier’s Story (2010) – all these narratives, and many more, tell the readers about the violent conflicts on the African continent and about the forced involvement of children in these wars. Yet none of these texts speaks about child soldiers as an exclusively African problem. Instead, what becomes clear from them is that the involvement of child soldiers in these conflicts is the result of the long-lasting effects of colonial oppression that largely destabilised the region (Honwana Citation2006, 7). Child soldiers in Africa are thus not the outcome of African ‘savageness’ – the racist view formulated by colonisers – but rather the reflection of the complex colonial and postcolonial histories.

In her recent study of child soldiers, Jana Tabak claims: ‘Child soldiers … are not only victims but traumatized victims, whose war experiences cause dysfunction and social instability’ (Citation2020, 115). She quotes a former child soldier from the Democratic Republic of Congo to illustrate the problem of dealing with and integrating former child soldier in society: ‘When I was in the militia I was used to being independent. It’s hard to go back living with parents after that. I didn’t like living with my parents. I’m a child, yes, in age, and in size I’m still small, but I know so many things about the world that nobody can joke with me or tell me what to do. I’m young in age and you can see that I’m small in size, but I’m not just a child. I know so much. Nobody can play with my life. I always go off on my own and survive. I don’t care’ (114; italics in original). And again, this opinion does not speak about the problem of child soldiers as a problem that exists on the African continent only. This is a global issue, and it is experienced differently by children worldwide. In words of Alcinda Honwana, ‘children affected by conflict – both girls and boys – do not constitute a homogeneous group of helpless victims but exercise an agency of their own, which is shaped by their particular experiences and circumstances’ (4). Yet Honwana emphasises that ‘social integration’ of such children can only be achieved through ‘social development and the eradication of poverty’ (4). This, in my view, only reinforces the problem of child soldiers as a (post)colonial (rather than African) issue. When tackling the problem of child soldiers from an ethical perspective, it is interesting to compare the respective perceptions of the child in the West and in Africa. Thus, ‘The African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (1990) defines a child as a person younger than eighteen years of age and does not stipulate a different age for non-participation in armed conflict’ (Kearney Citation2010, 71). Yet, ‘the distinction between childhood and adulthood in African societies is usually less clearcut than in Western societies: from an early age children are regarded as having the responsibility to contribute to the livelihood of their families.’ In addition, the relatively young populations of African counties – ‘fifty per cent or more of the population in every African country are under the age of 18’ – should also be taken into consideration, because it perhaps helps explain to some extent why there are large numbers of child soldiers in these places. In sum, to borrow from Honwana, children become involved in war because the meaning of ‘childhood’ has been transformed (4).

Members of certain criminal groups on the African continent might regard child soldiers as ‘normal,’ but others consider their recruitment and forced service to be abhorrent and illegal, and many people are the direct victims of this process – not only the child soldiers themselves but also their relatives and friends (who are also victims). Many Africans condemn such recruitment on moral grounds, actively resist it, and help former child soldiers rehabilitate. As for attitudes in the West, child recruitment is equated with child abuse and is legally recognised as a crime. Rosen provides a helpful explanation of how Western audiences perceive child soldiers:

[T]he very concept of the “child soldier” is intentionally constructed to conflate what in the West are two antithetical and irreconcilable terms. The first, “child,” generally refers to a young person between infancy and youth and is almost inseparable from ideas about immaturity, simplicity, and the absence of full physical, mental, or emotional development. The second, “soldier,” refers to adult men and women who are trained combatants. As a result, the concept of the child soldier fuses two very contradictory and powerful ideas, namely the “innocence” of childhood and the “evil” of warfare. Thus, from the outset, in the modern Western imagination the very idea of the child soldier seems both aberrant and abhorrent. (Citation2015, 175)

I would only emphasise here that such perceptions are shared by locals in the countries where children are recruited. To think otherwise would be to perpetuate stereotypes regarding the African continent and its black population, promoting what Robert Kaplan described as ‘the New Barbarism’ (qtd. in Rosen Citation2015, 23) decades ago and thus suggesting that ‘Africa and other places where child soldiers fight are inherently chaotic and apolitical’ (Rosen Citation2015, 183).

The ‘Western lens’ has not only largely promoted ‘media imperialism’ (Pettitt Citation2018, 176) and its distorted, racist, and ethically cruel messages regarding postcolonial spaces, but it has also oversimplified the complex issue of child soldiers in various ways. First, as Rosen notes, it has ‘Africanized’ the problem (Citation2015, 182). Second, it has generated images that characterise forced child military service as some ordinary, unfortunate, but easily forgettable event. Discussing Edward Zwick’s Blood Diamond (Citation2006) – a Hollywood perspective on resource extraction and child soldiers during the civil war in Sierra Leone – Teresa A. Booker (Citation2007) laments that the film fails to authentically portray the true trauma experienced by child soldiers: “[A]ny brainwashing, mental trauma, and physical abuse that child soldiers experience is not eliminated with a hug, no matter how unconditional the love of a compassionate father” (354). Despite these major failures, the cultural images of child soldiers that we now possess have an undeniable potency in communicating the existence of the problem of child soldiers, particularly to Western audiences. These portrayals have found means to make their important messages audible, serving as powerful accounts of humanitarian action.

Drawing child soldiers

Graphic narratives have taken up the problem of child soldiers and have effectively conveyed it to their readers. I focus here on 99 Days and Child Soldier and probe the ways they comment on the problem of forced military service for children and the trauma that inevitably results from such an experience. I will examine the use of their postcolonial settings as tools to reach Western audiences and will demonstrate how the graphic novel functions as an effectual medium for the representation of the problem of child soldiers.

In her exploration of comics as documentary, Hillary L. Chute (Citation2016) argues that even ‘after the rise and reign of photography … people yet understand pen and paper to be among the best instruments of witness’ (2). The scholar explains how ‘comics expresses history,’ meditating upon its nature: ‘comics is a drawn form; drawing accounts for what it looks like, and also for the sensual practice it embeds and makes visible.’ In addition,

the print medium of comics offers a unique spatial grammar of gutters, grids, and panels suggestive architecture. It presents juxtaposed frames alternating with empty gutters – a logic of arrangement that turns time into space on the page. Through its spatial syntax, comics offers opportunities to place pressure on traditional notions of chronology, linearity, and causality – as well as on the idea that “history” can ever be a closed discourse, or a simply progressive one. (4)

It is true that comics and graphic novels can engage with complex historical events, including war and genocide. The uniqueness of this medium helps convey certain messages in powerful and compelling ways. Not only what Chute terms its ‘unique spatial grammar’ allows this to happen; there is also what Nimrod Tal and I (Citation2018d) call its ‘visual-verbal peculiarity,’ which is ‘conjoint,’ i.e., ‘the verbal is not reduced to the text, and the visual is not merely about the image’ (8). This multilayered complexity, manifested through structure and arrangement as well as particular forms of visual and verbal aesthetics, makes comics and graphic novels a distinctive medium that succeeds in communicating known problems in a new way, providing novel perspectives on the matter and reaching a wide audience. Violence, which is a constituent part of war and genocide, can be particularly effectively portrayed in graphic novels. As Emily D. Edwards (Citation2020) suggests, this medium can turn violence into ‘graphic violence’ using different verbal and visual means ‘to create vivid, “graphic” imagery in the imagination (4).’ After all, as Edwards claims, ‘Pictures can be more explicit and relatable for some readers, which is a powerful advantage of pictures’ (4). This helps graphic novels convey the authenticity of conflict.

Structurally, 99 Days and Child Soldier diverge in their approaches to the problem of child soldiers. 99 Days comments on the horrifying transformations that such service exacts on a younger person, revealing in brutal detail what happens when one is forced to become not an honourable soldier but rather a criminal (a murderer, rapist, and drug addict) and a victim at the same time. In turn, Child Soldier romanticises the image of a child, offering a didactic explanation that situates childhood and soldiering as two areas that should not overlap. Both graphic novels therefore take up the ethical considerations involved in the child-soldiers problem, bringing to light the multifaceted nature of the issue.

99 Days focuses on the story of the Rwandan boy Antoine, whose family members were tortured and brutally murdered during the Rwandan genocide. The boy is later adopted by an American family, and the narrative is told from a present-day perspective (2010), at a time when Antoine, now an adult, is an LAPD detective. The memory of the genocide returns to him when a series of murders committed with a machete – the primary weapon used during the Rwandan genocide – starts taking place in Los Angeles, and Antoine, together with his colleague Valeria, begin to investigate.

Almost one million people died during the Rwandan genocide that took place in the spring of 1994, ‘one of the most concentrated acts of genocide in human history’ (Kayitesi-Blewitt Citation2006, 316). The genocide spread at breakneck speed, and yet the international community took no adequate action, which indeed ‘revealed its racist attitude … to the problems of [a] country populated by black people’ (Prorokova Citation2018a, 65). The genocide – the slaughter of Tutsi and moderate Hutu conducted by extremist Hutu – was a manifestation of ethnic hatred deriving from the colonial era, when racist colonisers privileged one ethnic group, the Tutsi (having defined them as ‘biological[ly]’ closer to the white race), over another one, Hutu (Mirzoeff Citation2005, 37).

Antoine himself is a Hutu, yet his family is murdered by a group of extremist Hutu because they had helped several Tutsi to hide and thus escape the slaughter. Antoine’s life is spared only because he is a teenage Hutu boy whom the insurgents believe can help them fight the war against the Tutsi and the moderate Hutu. He is turned into a child soldier. Yet 99 Days only gradually informs the reader about what really happened in Rwanda in 1994, through occasional flashbacks provoked by scenes in LA that are allegedly reminiscent of the genocide’s events. Of course, the graphic novel makes it clear that the memory of the genocide has never really left Antoine – it opens with the image of two boys, Antoine (as the reader later finds out) and a Tutsi companion, whose face has been mutilated by machete cuts. The reader, turning the page, is transported to Los Angeles in 2010, as Antoine wakes up from his nightmare. 99 Days introduces what I dub ‘the haunting power of war’ (Prorokova Citation2018b, 188), immediately plunging the reader into the atmosphere of psychological uneasiness experienced by war survivors for the rest of their lives, unable to erase the memories of the atrocities that they witnessed, committed, or were victims of.

The graphic novel plays with the past and the present, thus intensifying the story’s suspense, for Antoine’s experience in Rwanda is recounted only in smaller portions than those of the primary plot, which is focused on Los Angeles. Laurike in ‘t Veld argues: ‘In a twist on … [various] intertextual references, the comic couples the highly generic format of the detective story with the solemnity of the genocide narrative. Through its comparative set-up, the comic continuously re-appropriates the Rwandan genocide into an American context’ (139). in ‘t Veld continues:

[T]he integration of the genocide narrative with the detective genre generally seems to work out in favour of the detective format, with a decided move to place elements of the Rwandan backstory into an American context. This leads to some poignant ethical considerations, particularly in the case of the links drawn between the perpetrators of genocide and the American gang members, as well as the problematic lack of context on the Rwandan genocide. (141)

I agree that the novel perpetuates racism by overtly comparing African American victims in LA to African victims in Rwanda and by drawing parallels between the extremist Hutu and the criminals in Los Angeles, which serves, among other effects, to belittle or even silence the tragedy of Rwanda. But I also see an advantage in the graphic novel’s strong preference to talk about the crimes in Los Angeles rather than to present every detail of the much more brutal and horrifying story of the Rwandan genocide. This decision, I argue, serves a purpose, too. Reducing the Rwanda plotline to a minimum, 99 Days paradoxically manages to tell us more about the genocide’s violence. The suddenness of the flashbacks, which instantly situate the reader in the midst of the slaughter, intensifies the war’s horror, suggesting that for an unprepared audience, this information should indeed be communicated in carefully administered instalments rather than all at once. It is striking that because of these flashbacks, the Los Angeles murders, though drawn in a very graphic, explicit way, appear less brutal than they were perhaps intended to be, a diminishment that reinforces the brutality of the genocide. In addition, the graphic novel manages to effectively juxtapose the U.S. and Rwanda, suggesting that even the most horrifying of the Los Angeles murders pale in comparison to the slaughter committed during the genocide. Images of the victims, thus politicised, are used to criticise the lack of effective international intervention in Rwanda in 1994.

In terms of structure and organisation, or, to borrow Chute’s term again, its ‘unique spatial grammar,’ 99 Days effectively arranges the past and the present with the help of both colour and the panels’ ordering. As I have argued elsewhere, usually ‘the use of black and white helps juxtapose past and present’ (Prorokova Citation2018b, 194). Yet the novel is drawn fully in black-and-white, which creates an atmosphere of haunting, ‘merging past and present, revealing that the memories from Antoine’s past literally live in his present’ (194). As for the organisation of the panels, it is crucial that ‘the panels that describe events in Kigali and Los Angeles are never intermingled on one page,’ i.e., ‘just as the United States and Africa [Rwanda] belong to different spheres of the world, so too do the stories in the book have their own distinct spaces’ (195). This not only reinforces the authority of the images showing the genocide, whose number is considerably lower than that of the images depicting the events in Los Angeles, but it also helps convey the message that lives matter no matter how far away they might be, regardless of where these people are situated in the world. Moreover, as in ‘t Veld claims, ‘By creating a link between the two storylines, it is signalled that the two places work as mutual lenses through which we can re-interpret the situations and actions that occur’ (142). This, in turn, foregrounds the graphic narrative’s essential quality that results from ‘[the] [u]s[e] [of] the necessary contiguity of panels to create suggestive but subliminal connections which need not correspond to the linear logic of the narrative sequence’ (Joseph Witek qtd. in in ‘t Veld Citation2015, 142).

99 Days’ discussion of the Rwandan genocide is largely filtered through the prism of the child-soldiers issue. After Antoine is forced to join the perpetrators of the genocide, he gradually undergoes radical transformations, which effect his metamorphosis from loyal citizen to merciless murderer. First, Antoine is drugged. Marijuana is described as a weapon that extremist Hutu use to brainwash and subjugate their younger soldiers. One of the soldiers says to Antoine: ‘See? It’s the powder, man. The one the captain uses to spike those up for us. I’ve seen ’em doin’ it, man. Y’smokin’ gunpowder with that … crap’ (Casali and Donaldson Citation2011, 103; bold in original). In addition to smoking weed, the soldiers are observed consuming highly potent alcohol, which evidently only reinforces the weed’s effects. Antoine is also turned into a rapist. Crucially, this happens while he is made malleable through a continuous stream of strong alcohol. Before he is ordered to rape a Tutsi woman, he is given a bottle of Jack Daniels, and the reader observes the already-drunk and exhausted Antoine grabbing a bottle and drinking more. It is also pivotal that although Antoine is referred to as a ‘kid’ during the murder of his family (75), he is now recognised by the insurgents as a man: one of the rebels gives Antoine the bottle, saying, ‘You a man now, boy. And men drink the best stuff around’ (120; bold in original; my italics). Note how through alcohol consumption – an exclusively adult activity – the insurgent attempts to impose adult status onto the child, yet arguably he understands the criminality of his actions, for referring to Antoine as both ‘man’ and ‘boy’ within one sentence, the extremist Hutu emphasises the criminal nature of child soldiers – kids who are forced to become adult criminals. In that sense, Antoine’s mumbling ‘I’m … I’m sorry, I … ’ (121; bold in original) right after he has raped the woman poses a serious ethical concern, equally foregrounding the problems of rape and of child soldiers who are made to commit crimes. Antoine, now portrayed as a rapist, is, crucially, a victim, just like the woman he has raped. Not acknowledging this complicated double status would risk diminishing the problem of child soldiers and reinforcing the image that these children are pure criminals and are not themselves victims.

Smoking weed, drinking strong alcohol, raping women, and being forced to regularly perform the orders of extremists doubtless changed Antoine. Yet the larger transformation in his character takes place later – only at the end of the graphic novel is the reader informed about the event that irrevocably changed the boy. During the genocide, Antoine was ordered to slaughter his Tutsi friend with a machete. A group of Hutu extremists warns Antoine that if he does not carry out the murder, they will set loose a hyena, who will attack and eat them both. In panic and fear, Antoine mercilessly murders his friend: ‘I went at him faster than the hyena. I scared the beast. I became one myself’ (Casali and Donaldson Citation2011, 171; bold in original). To analyse this scene, in ‘t Veld’s concept of ‘the animal metaphor’ is particularly helpful. The scholar argues: ‘The animal metaphor of the hyena is used as a powerful visual device that raises questions about guilt and responsibility’ (141). Moreover, ‘The hyena functions as a reminder of dehumanisation strategies employed by perpetrators and it also marks the speed with which others can become dehumanised in the process’ (150). In the context of child soldiers, the animal metaphor helps reinforce the notion that these children’s lives have little significance for the insurgents, who regard the forced recruits indeed not as equals but as objects to be trained (just like dogs) so that they can execute the most savage orders; their deaths would not mean anything, for the insurgents will simply recruit new children and use them as they will.

The straightforwardness with which the problem of child soldiers is conveyed in 99 Days, including the references to drug and alcohol consumption, rape, and murder (all of which are graphically depicted in the novel), can be contrasted to the somewhat more moderate depiction one encounters in Child Soldier: When Boys and Girls Are Used in War. Although Child Soldier seems far less brutal than 99 Days, it nonetheless successfully tells an accurate story of child abuse in war.

A somewhat childish tone adopted in the narrative can easily be explained by the age of the boy protagonist. When the story begins in 1993, he is five years old. The Democratic Republic of Congo wrested independence from its Belgian colonisers in the 1960s but by the 1990s the political situation in the country had fully collapsed. In very pleasant and attractive colours, and through friendly, smiling characters, Child Soldier narrates the story of Michel Chikwanine, whom we find surrounded by his loving parents and friends. The boy is warned that he can play outside only until 6 p.m. Once, he breaks the curfew and, kidnapped by insurgents, he is made into a child soldier. Most of the novel focuses on Michel’s life as a child soldier until his escape, as well as on his rehabilitation and immigration to Canada.

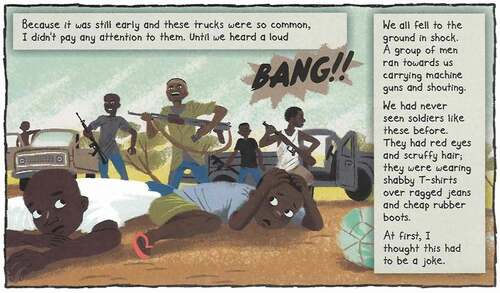

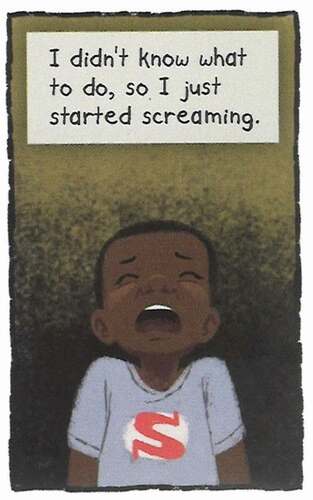

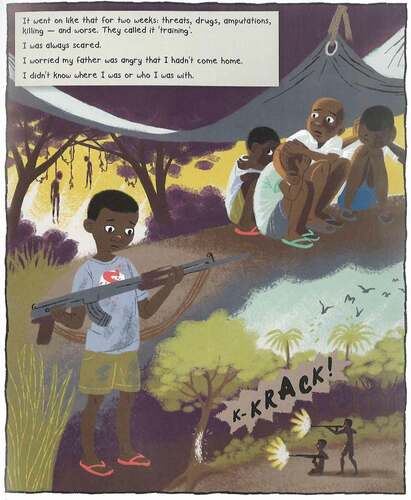

The innocence of the child is largely emphasised through the book’s imagery. Both when the boy is being kidnapped (see ) and when he is brought into a training camp (see ), his vulnerability and helplessness are foregrounded through his age and through the behaviour that is typical of his phase of youth.

Figure 1. Michel and other boys are kidnapped by the rebels (Humphreys, Chikwanine, Dávila Citation2015, 13).

Figure 2. Scared of the shooting, Michel starts to scream (Humphreys, Chikwanine, Dávila Citation2015, 15).

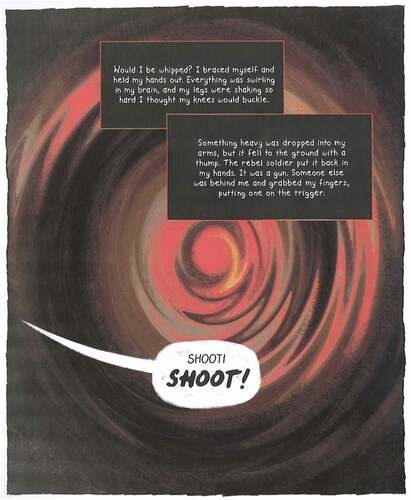

Rather soon, Michel is forced to commit his first kill. A sense of the horrific psychological abuse is again effectively communicated through the visuals. As the boy is blindfolded and a gun is put into his hands, the reader is invited to experience the boy’s feelings through a large image that mixes red, brown, black, and yellow – symbolising the uncertainty, fear, and shock that the boy feels as he is ordered to pull the trigger (see ).

Figure 3. Michel is blindfolded, unaware of what is going to happen next (Humphreys, Chikwanine, Dávila Citation2015, 18).

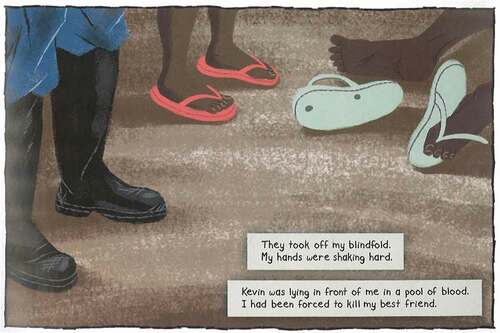

As the blindfold is taken off, Michel realises what he has just done: ‘Kevin was lying in front of me in a pool of blood. I had been forced to kill my best friend’ (Humphreys, Chikwanine, and Dávila Citation2015, 19). Yet note the marked difference in how a child soldier’s murder of his best friend is portrayed in this graphic novel (see ) as compared to the images given in 99 Days (see page 171).

Figure 4. Michel realises he has just murdered his best friend (Humphreys, Chikwanine, Dávila Citation2015, 19).

Unlike 99 Days, Child Soldier does not show any blood; neither the boy’s corpse nor Michel’s reaction are ever revealed. The decision to show no overt visual violence in this graphic narrative suggests that unlike 99 Days, Child Soldier is also intended for younger readers. But the lack of blood is a powerful means as well to intensify the gap in comprehension among children forced to fight, who do not grasp what they are doing and why they are doing it. The absence of pools of blood and dead bodies mimics a child’s consciousness: real-world violence, murder, and abuse are simply not part of (or should not be part of) this phase of development. Even when corpses are depicted in Child Soldier, their appearance is largely distorted in such a way that they are not recognised as dead humans but rather are merged with the landscape (see ). Nonetheless, violence and abuse are clearly part of the boy’s experience: ‘It went on like that for two weeks: threats, drugs, amputations, killing – and worse. They called it “training”’ (23). And while this terrible experience is happening, Michel, apart from being ‘always scared,’ also expresses a purely childish fear: ‘I was worried my father was angry that I hadn’t come home’ (23). The boy’s childish innocence is also emphasised through the image of him holding a rifle: the size of the weapon accentuates how small its holder is, while Michel’s bewildered look reveals that the boy is not so much scared as he is simply unable to understand why he has been given this weapon and how or when he is supposed to use it (see ).

Figure 5. Michel is inspecting a rifle. Note human copses hanging off the trees in the background that are almost indistinguishable from the trees. Drawn to mimic the landscape, they are not easily noticeable by younger readers, yet their presence is a significant means to render the violence of the environment that the children are living in (Humphreys, Chikwanine, Dávila Citation2015, 23).

Michel manages to escape, yet ‘[b]ack home, things went on, but they were never the same’ (Humphreys, Chikwanine, and Dávila Citation2015, 29). Not only has the boy changed, the town has been transformed, too. Michel stresses that his hometown ‘had been the safest place in the world to be a child’ (29), breaking with the racist stereotype that ‘Africa’ is a dangerous place and suggesting that the issue of child soldiers is as scary for the locals as it is for Western audiences. And yet, just as Antoine in 99 Days can never forget his experience of being a child soldier and the fact that he has witnessed and committed crimes, so too is Michel haunted by his memories, as he tells us: ‘[My father] wanted to protect me from myself, from my memories’ (29). Both graphic novels thus comment on the profound trauma experienced by child soldiers, and it does not matter whether they are as small as Michel or are already teenagers like Antoine, for ‘repressed and/or suppressed memories are carried over into the future and come to surface or sink out of social consciousness in a fluid engagement with the past that morphs over time and across generations’ (Gammage Citation2016, 406–07).

Just as Antoine became a refugee and, having been adopted, moved to the U.S., Michel, together with his mother and one of his sisters, after years of waiting, moves to Canada: ‘Six years later, Mum, Marizia and I were finally allowed to move to Canada. My older sisters stayed behind. The refugee laws at that time only allowed children under 18 to go with their parents. Vicky made her own refugee claim and joined us a couple of years later. But Viviane never made it out. Neither did my father’ (Humphreys, Chikwanine, and Dávila Citation2015, 39). This time, via the example of Canada, the reader is again invited to ponder the opposition between an African county (Congo) and a Western country. This new place appears alien to Michel, for the kids there worry about their mobile phones, their problems at school and with their parents, how warm their pizza was served, and other issues that clearly appear insignificant compared to what Michel has experienced as a child soldier. Yet having realised that this issue is simply unknown to the children in Canada, Michel decides to talk about it, including through the publication of Child Soldier, which becomes a tool to communicate about and fight against child abuse and forced military service.

Conclusion

Graphic narratives are a powerful medium to convey such a complex issue as the continued recruitment and use of child soldiers around the world. As 99 Days and Child Soldier demonstrate, there are different ways to approach the problem; intentions can be different, too. Both texts focus on the issue of child soldiers in African countries – Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo, respectively – and both build bridges with the West, transferring their characters to the U.S. and Canada, respectively, after they have endured the ordeal of war. The primary aim of both graphic novels in their discussion of child soldiers is to display the horrifying consequences that such an experience has on children, changing them, troubling their psyche, transforming their views. Whether being more explicit regarding crimes committed by child soldiers, as in 99 Days, or remaining somewhat cautious, as in Child Soldier, both narratives successfully draw attention to the phenomenon of child soldiers itself as a crime, never accusing the protagonists but instead inviting the reader to look at them as victims.

Both graphic novels interpolate the issue of memory in their stories of child soldiers, displaying forced military experience as a haunting event. As I have argued elsewhere,

‘War continues living in collective memory, for its history (constructed out of collective and individual experiences alike) is transmitted from one generation to another. However, within a narrower scope, war also becomes part of the personal experience of those who live through it – experience that is then transformed into memories that take on an individualised cast’ (Prorokova Citation2018b, 188). War transforms everyone; yet being forced to fight (especially at a young age) is an experience far more stressful, violent, and uncertain than less coercive experiences. And the two graphic novels effectively illustrate this additional, burdensome intensity borne by the young recruits. In addition to reflecting the construction of the protagonists’ traumatic memories, the graphic narratives also help create a form of historical memory about forced child military service in Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Joanne Pettitt claims that ‘comic books and graphic novels rely on active reader responses, creating a dynamic process of interpretation that is closely linked to constructions of memory’ (174). In that sense, both 99 Days and Child Soldier, through various visual, verbal, and structure-related techniques, enable the reader to witness the history of child abuse in two distinct countries, transforming historical memory about child soldiers from a local matter to something of global concern.

Finally, by connecting the two African countries to two North American countries, the graphic novels successfully transform the issue of child soldiers from a dilemma confined to the postcolonial world to an ethical conundrum that asks for awareness on the part of people everywhere. The transatlantic nature of these texts helps turn the problem of child soldiers into a transatlantic problem, blurring borders between postcolonial spaces and the rest of the world and inviting the world to witness and help solve this grave issue. And while ‘[t]he child’s inherent vulnerability and inevitable powerlessness to withstand [various abusive regimes] … created and imposed by grown-ups, i.e. those who are in all senses stronger than children – seem to foretell the tragic endings of such [narratives]’ (Prorokova Citation2018c, 380), the survival of the protagonists in 99 Days and Child Soldier should by no means minimise the importance of the problem but instead should be considered a special technique, in which communicating this problem (but not forgetting or silencing it) is at its core.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Tatiana Prorokova-Konrad

Tatiana Prorokova-Konrad is a postdoctoral researcher at the Department of English and American Studies, University of Vienna, Austria. She holds a PhD in American Studies from the University of Marburg, Germany. She was a Visiting Researcher at the Forest History Society (2019), an Ebeling Fellow at the American Antiquarian Society (2018), and a Visiting Scholar at the University of South Alabama, USA (2016). She is the author of Docu-Fictions of War: U.S. Interventionism in Film and Literature (University of Nebraska Press, 2019) and a coeditor of Cultures of War in Graphic Novels: Violence, Trauma, and Memory (Rutgers University Press, 2018).

References

- Blood Diamond. 2006. Directed by Edward Zwick, performances by Leonardo DiCaprio, Jennifer Connelly, and Djimon Hounsou, Warner Bros.

- Bodineau, S. 2014. “Vulnerability and Agency: Figures of Child Soldiers within the Narratives of Child Protection Practitioners in the Democratic Republic of Congo.” Autrepart 4 (72): 111–128. doi:https://doi.org/10.3917/autr.072.0111.

- Booker, T. A. 2007. “Blood Diamond, Directed by Edward Zwick, Produced by Paula Weinstein, Edward Zwick, Marshall Herskovitz, Graham King, and Gillian Gorfil.” Political Communication 24 (3): 353–354. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10584600701472961.

- Briggs, J. 2005. Innocents Lost: When Child Soldiers Go to War. New York: Basic Books.

- Casali, M., and K. Donaldson. 2011. 99 Days. New York: DC Comics.

- Chute, H. L. 2016. Disaster Drawn: Visual Witness, Comics, and Documentary Form. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Edwards, E. D. 2020. Graphic Violence: Illustrated Theories about Violence, Popular Media, and Our Social Lives. New York: Routledge.

- Gammage, J. O. 2016. “Trauma and Historical Witnessing: Hope for Malabou’s New Wounded.” The Journal of Speculative Philosophy 30 (3): 404–413. Accessed 5 April 2019. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/628670

- Haer, R. 2019. “Children and Armed Conflict: Looking at the Future and Learning from the Past.” Third World Quarterly 40 (1): 74–91. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2018.1552131.

- Hirsch, J. 2004. After Image: Film, Trauma, and the Holocaust. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Honwana, A. 2006. Child Soldiers in Africa. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Humphreys, J. D., M. Chikwanine, and C. Dávila. 2015. Child Soldier: When Boys and Girls are Used in War. London: Franklin Watts.

- in ‘T Veld, L. 2015. “Introducing the Rwandan Genocide from a Distance: American Noir and the Animal Metaphor in 99 Days.” Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics 6 (2): 138–153. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21504857.2015.1027941.

- Kayitesi-Blewitt, M. 2006. “Funding Development in Rwanda: The Survivors’ Perspective.” Development in Practice 16 (3/4): 316–321. Accessed 9 April 2019. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4030061

- Kearney, J. A. 2010. “The Representation of Child Soldiers in Contemporary African Fiction.” JLS/TLW 26 (1): 67–94.

- Kozlovsky Golan, Y. 2011. “‘Au revoir, les enfants’: The Jewish Child as a Microcosm of the Holocaust as Seen in World Cinema.” Shofar: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Jewish Studies 30 (1): 53–75. Accessed 5 April 2019. https://muse.jhu.edu/journals/sho/summary/v030/30.1.golan.html

- Mihăilescu, D. 2014. “Traumatic Echoes of Memories in Child Survivors’ Narrative of the Holocaust: The Polish Experiences of Michał Głowiński and Henryk Grynberg.” European Review of History: Revue Europeenne D’histoire 21 (1): 73–90. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13507486.2013.869791.

- Mirzoeff, N. 2005. “Invisible Again: Rwanda and Representation after Genocide.” African Arts 38 (3): 36-39+86-91+96. Accessed 9 April 2019. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3345921.

- Pettitt, J. 2018. “Memory and Genocide in Graphic Novels: The Holocaust as Paradigm.” Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics 9 (2): 173–186. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21504857.2017.1355824.

- Prorokova, T. 2018a. “Shaming the West: The Other Side of the Rwandan Genocide in Film.” In The Rwandan Genocide on Film: Critical Essays and Interviews, edited by M. Edwards, 62–79, Jefferson, McFarland.

- Prorokova, T. 2018b. “The Haunting Power of War: Remembering the Rwandan Genocide in 99 Days.” In Cultures of War in Graphic Novels: Violence, Trauma, and Memory, edited by T. Prorokova and N. Tal, 188–203, New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

- Prorokova, T. 2018c. “The Holocaust in Film: Witnessing the Extermination through the Eyes of Children.” Holocaust Studies: A Journal of Culture and History 24 (3): 377–394. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17504902.2017.1411645.

- Prorokova, T., and N. Tal. 2018d. “Introduction.” In Cultures of War in Graphic Novels: Violence, Trauma, and Memory, edited by T. Prorokova and N. Tal, 1–19, New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

- Rosen, D. M. 2012. Child Soldiers: A Reference Handbook. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO.

- Rosen, D. M. 2015. Child Soldiers in the Western Imagination: From Patriots to Victims. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

- Shail, R. 2014. “Anarchy in the UK: Reading Beryl the Peril via Historic Conceptions of Childhood.” Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics 5 (3): 257–265. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21504857.2014.913645.

- Sharkey, D. 2012. “Picture the Child Soldier.” Peace Review 24 (3): 262–267. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10402659.2012.704232.

- Singer, P. W. 2006. Children at War. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Tabak, J. 2020. The Child and the World: Child-Soldiers and the Claim for Progress. Athens: University of Georgia Press.