ABSTRACT

This article offers a visual discourse analysis of the Marvel comic superheroine Black Widow in the 2010 miniseries Black Widow–Deadly Origins, the 2016 Black Widow–S.H.I.E.L.D.’s Most Wanted series and issues 103 and 104 of Tales of Suspense from2018. Focusing on issues of gender and cultural representation, it identifies the Widow as a figuration of Russia through the tropes of the ballerina and the trauma patient. It shows how the comic books deploy the comic form to create visual narratives on the intersection of gender and trauma. Furthermore, it analyzes how the images of the Widow bring forward trauma and at the same time confirms symbols, images and ideas about Russia. To argue that the meaning of trauma embodied by the Black Widow is a symbol for Russia as such, the article contextualises the individual visual and textual narratives of current Black Widow iterations within the long history of the Black Widow figure as point to negotiate the relationship between the USA and Russia within the Marvel comic universe. Thereafter, it relates contemporary imaginations about Russia through the figure of the Black Widow to current and long-standing cultural ideas about the Russian country, history and its people.

This article offers a visual discourse analysis of the Marvel comic miniseries Black Widow–Deadly Origins (Cornell et al. Citation2010a, Citation2010b, Citation2010c, Citation2010d), the Black Widow–S.H.I.E.L.D.’s Most Wanted series (Waid, Samnee, and Wilson Citation2016) and issues 103 and 104 of Tales of Suspense (Rosenberg, Foreman, and Rosenberg Citation2018a, Citation2018b). I analyse the visual and narrative construction of the superheroine Black Widow and her agency, paying special attention to aspects of gender, mental dis/ability, and ethnicity. I identify two distinct gendered tropes structuring the Black Widow: the ballerina and the trauma patient. Drawing on the feminist cultural studies scholar Kimberly Williams I show that both tropes are adaptations of two long-standing American Russia imaginaries, the ‘femme fatale’ and the ‘ill patient’ (Williams Citation2012, 61, 122), that signify the Widow not only as Russian but as metaphor for Russia itself.

Referring to works from feminist cultural studies (Williams Citation2012; Doane Citation1991) I locate trauma on multiple levels of the Widow figure and narrative: as aspect of the femme fatale, as part of her story, as cultural reference and as narrative function. Following the feminist comic studies, scholar Hillary Chute’s work on trauma memories in comics (Chute Citation2010) I will show that the Black Widow comics deploy the comic form to create visual narratives that mimic trauma memory, a memory fragmented in individual images, to bring forward and confirm symbols, images and ideas about Russia. I will contextualise the individual visual and textual narratives within the long history of the Black Widow figure within the Marvel comic universe to expound that more current comic books continue to proliferate long-standing cultural sentiments about the country and its people.

Eastern dancer, deadly spider, femme fatale

The first Black Widow already appeared in 1940. Her name was Claire Voyant and she was resurrected by Satan to do his bidding. However, there is no known direct link to the later Russian Widow. Stan Lee, N. Korok and Don Heck created the latter for Tales of Suspense issue 52 (Citation1964). Today she is also known by her civilian name Natasha Romanova or Romanoff. While she was originally sent to steal military secrets from Tony Stark, aka Iron Man in service of the Soviet leader Josef Stalin, she later defected and has since worked as a superspy in service of US interests.

The fact that the Widow was created as antagonist of Iron Man is significant. Matthew Costello, who analyses the negotiation of American identity within Cold War comics, points out that the Iron Man storyline ‘represented the moral certainties of the Cold War, with plot lines that defined the conflict in stark contrasts between good and evil’ (Costello Citation2009, 63). The male figures’ bodies corresponded to this black and white thinking. The Soviets visually represented ‘the communist enemies [in a way that] reinforced the assertion of the moral superiority of America, [through] racial stereotyping’ (Costello Citation2009, 63). They were contrasted to the ‘blond, blue-eyed Steve Rogers (Captain America) [or] the urbane and sophisticated Tony Stark (Iron Man), [both] handsome and, by association, virtuous’ (Costello Citation2009, 64). Although he mentions her briefly, Costello does not analyse the Widow. Thereby, he misses the opportunity to recognise the gendered structures of American Cold War cultures that translated so smoothly into current New Cold War discourses.

The figure of the Black Widow differed significantly from the male Soviet antagonists in the Iron Man comic books, not the least through her gender. In differentiation to the ugly male villains, the female antagonist Madam Natasha, aka the Black Widow, is appealing to the protagonist of the comic, and probably equally to the readers. Her hourglass figure, long legs, cat eyes and petite nose conform to the beauty standards of the 1960s, prompting Tony Stark to the thought ‘What a beauty she is’ (Lee, Korok, and Heck Citation1964, 4). Her beauty distinguishes her from the other Russians/Soviets. It relates to and emphasises the idea that Madam Natasha is not bad per se but has been traumatised and victimised, manipulated and weaponised by the Soviets. Her beauty, smarts and fear of her Soviet superiors (Lee, Korok, and Heck Citation1964, 13) make her a likeable character, rather than a classic villain. During her first appearance, it is only suggested that she could be transformed if she only had the right American mentors. In subsequent issues the story line that presents her as a victim of Soviet manipulation becomes substantiated and she performs the transformation from the bad to the good side, and starts defending American values.

Although not marked as evil through physical aspects, her body, nevertheless, speaks to her character and its Russian or Soviet heritage. Given that the colour red was one of the official colours of communism and that a widespread American popular culture reference to communists was ‘Reds’ (Heller and Barson Citation2001), the Widow’s red hair can be interpreted as reference to communism. Her long legs as well as elegant and sophisticated posture, on the other hand, speak to her royal heritage (as Romanova) and her training as a Russian prima ballerina (I will come back to this aspect in the next section).

Additionally, her long muscular limbs visually relate to the features of the Spider. Like the North American black widow spider, the Widow’s curvy body is predominantly black, tightly wrapped in black fabric, and her symbol is the hourglass-shaped red mark that is similar to the one that the spider has (Waid, Samnee, and Wilson Citation2016). The likeness of her body to the spider and her name indicate danger, especially for the male sex. The female black widows are highly venomous; their venom causes nausea, goosebumps, and sweating – symptoms not unlike one experiences in case of sexual attraction. Moreover, the female black widow consumes the male after courtship. In combination with the described above clear attachment to Russian communism, the signification of danger not only indicates the Widow as dangerous female but also marks her country of origins and its political ideology as dangerous.

The dangers of Soviet Russia and its ideological successor become visible in the storyline of the Red Room, which reappears in all of the issues analysed in this article. In the Soviet Russian military facility called the Red Room the Widow and ‘27 original Black Widow agents [were] trained […] from girlhood to be perfect killing machines: chemically enhanced for performance, psycho-chemically conditioned, and implanted with false memories to be loyal’ (Morgan, Parlov, and Sienkiewicz Citation2005b, 1). There the Widow has been made to embody the archetype of a femme fatale.

This idea of the femme fatale stuck to the Widow from her first appearance onward. Already Tales of Suspense #52 introduces her as ‘a real Mata Hari’ (Lee, Korok, and Heck Citation1964, 13) as a reference to the Dutch exotic dancer convicted of spying for the Germans during World War I. This reference highlights the Widow’s characteristics that match Mary Ann Doane’s description of the archetype of the femme fatale. According to Doane, a typical femme fatale ‘never really is what she seems to be: [she] transform[s] the threat of the woman into a secret, something which must be aggressively revealed, unmasked, discovered’ (Doane Citation1991, 1). Part of the Widow’s secret is her mysterious, yet distinctly Eastern European origin, indicated by her civilian name Romanova (Lee et al. Citation1972, 8; Cornell Raney, and Hanna Citation2010a, 13). Being ethnically marked through this name, in turn, reconfirms her status as femme fatale. It does so by alluding to the common cultural stereotype of the Eastern European woman as ‘alluring, slightly Oriental or exotic temptress with an edge of vampirism’ (Glajar and Radulescu Citation2004, 6).

As Eastern European figure of secrets, the Widow bears what Doane calls ‘a certain discursive unease, a potential epistemological trauma’ (Doane Citation1991, 1) that is typical for the femme fatale: the possibility of disrupting our knowledge about and understanding of the ‘truth,’ certainty and control. In the following sections, I will identify aspects of cultural trauma, memory loss and trauma memory in the Black Widow comic stories. Moreover, I will show how these narrative aspects are connected to the trope of the femme fatale and her potential for epistemological trauma. I will do so by building on the thesis that the Widow’s secrets and the psychological irritation, created by the unravelling of her personal history, motivate her narrative and are mirrored by the readers’ desires: ‘the entity whose self-identity has been disrupted is only able to reconstitute it by getting to the end of the story, by revealing the truth that lies beyond the surface ambiguity’ (Williams Citation2012, 122).

The Black Widow as embodiment of Russia’s historic traumas

Comic studies scholars such as Zak Roman and Lizardi (Citation2019) have shown that superhero/ine comics have historically negotiated US identity and its relationship to other nations. Others, such as José Alaniz (Citation2014) and Scott Bukatman (Citation2003), have emphasised that this negotiated US identity more often than not centres around the experience and overcoming of traumas concerning ‘national, ideological, and sexual myths’ (Alaniz Citation2014, 17). While the Widow equally thematises belonging to the US nation and negotiates American values through her work as Avenger and agent of S.H.I.E.L.D., she does so by offering the comparison between the (good) US to (bad) Russia. Importantly, while she has to work through her multiple traumas to delineate for herself and the reader good American values, much like other superhero/ines, her trauma narratives in differentiation to these others’ are not connected to the US and its history, but are all connected to Russia. Multiple of these trauma narratives concern the history of Soviet inhumanity, authoritarianism and the abuse of Russian people. Already in Tales of Suspense #52 (Lee, Korok, and Heck Citation1964, 10), the reader learns that Soviet soldiers and spies need to fulfill their mission or they have to die for their failures. This inhumane authoritarian approach is explicitly contrasted to the American way, where the individual is valued and mercy is shown even to enemies (Lee, Korok, and Heck Citation1964, 3). The idea of Soviet terror goes back to what became known as ‘Order No. 270,’ issued by Josef Stalin on 16 August 1941 during the Axis invasion of the Soviet Union, that commanded the Red Army soldiers to ‘fight to the last’ and virtually banned them from surrendering by requiring superiors to shoot deserters on the spot (Roberts Citation2006, 98). This ideology is visually depicted through groups or masses of uniformly drawn Soviet soldiers (Lee, Korok, and Heck Citation1964, 10), uniform Russian ballerinas and clones (I will come to this point in the following sections) set against the brightly coloured and individually distinct Americans.

Another trauma of Soviet origins is indicated by the Widow’s civilian name Romanova, which refers to the Tsar family who were murdered on 18 July 1918. Although it is unclear when exactly it was revealed that Madame Natasha’s (Lee, Korok, and Heck Citation1964) last name is Romanova, the name can be found in all issues that feature the Widow following Daredevil issue 88 (Lee et al. Citation1972). The connection between the name Romanov and the murder of the Russian Tsar family was established within American popular culture memory by the first Twentieth Century Fox film Anastasia in 1956, featuring Ingrid Bergman (Williams Citation2012, 70) as (fictional) lone survivor of the Romanovs. It was further popularised by the second Twentieth Century Fox animated film Anastasia in 1997.

The Deadly Origins miniseries explicitly present the Widow as heir of the royal family. It depicts the civil war, and the death of the Widow’s mother; the scene visibly fictionalises historic events. The text describes the confrontation between the White Army and the Bolsheviks but transfers the historic civil war from 1918 to 1928 and locates the characters in the fictional city of Talingrad (Cornell et al. Citation2010a, 13). The name, especially in combination with the images of complete destruction could also refer to the infamous battle of Stalingrad between the Nazis and the Red Army in 1942/43.

These skewed but still identifiable references to historic places and events can be read with the trauma studies scholar Dijana Jelača as a visualisation of ‘traumatic memory’ (Citation2016, 11). Such a memory ‘often alters the way facts are perceived’ (Jelača Citation2016, 11). The distorted, yet specific places and dates, connecting the Widow to Russian historic events, can be read with Jelača as trauma storytelling rather than details provided for historical accuracy. The murder of the Romanovs, the disregard for the lives of the individual soldiers during World War II, and the individual personal experience during her spy training merge into a single message about the Widow’s place of origin as a place of multiple traumas. The traumatic memories connecting the Widow to the tragic story of Russia are coloured in different shades of brown, yellow and orange (Cornell et al. Citation2010a, 13). The colours mirror the scene that shows a wooden building going up in flames and Soviet soldiers in their brown uniforms. The differently sized sepia-coloured images reminding of old-fashioned photographs are surrounded by a white gutter. The white cracks imitate historic photographs further, looking like kinks or small tears on the photo surface that reveal the white paper beneath. Presenting memories as photographs in the process of deteriorating, paling or tearing additionally indicates the instability of memory and identity; it is enhanced even further by the uncertainty and lack of clarity of the exact historic events they show.

In their ‘inadequate relationship to past events’ the Widow’s trauma memories emphasise ‘their recurring role in the present’ (Jelača Citation2016, 11). In the present, the Widow’s personal traumas become connected to issues of identity loss (Cornell et. al Citation2010b). Interestingly, this idea already came up in the ‘Widow’ issues of Marvel Fanfare (Macchio and Pérez Citation1983). There the potential undoing of her identity through a confrontation with her trauma is visually illustrated through an image that triples Romanova’s face: one wearing a widow’s veil turned to the left; a crying one frontal; one with angrily bared teeth and contorted eyebrows turned to the right.

In Deadly Origins issue two (Cornell et. al Citation2010b, 6–7), the Widow is multiplied to signify identity loss during the confrontation with trauma (I will come back to the significance of multiplication in the next section). This time, however, she is not shown in different versions of her contemporary self, in different states of mind and poses, but in different versions of herself at different times. Additionally, the elements and scenes assembled alternate between the reality and those false memories the Soviets artificially implanted in her brain. The assemblages show the Widow in a state dislocated from space and time. On the verge of spinning out of control, she realises she had been brainwashed and used by evil forces but is able to snap out of the state of confusion and commit anew to fighting for American values.

The multiple scenes that intersect in the pages discussed metaphorically create the Widow’s mind, conjuring up the common female figure of Russia as the ‘pathologically ill patient’ (Williams Citation2012, 61). Simultaneously, the individual scenes and memories emphasise her physical attributes, especially her allure as femme fatale. Both the femme fatale and the pathologically ill patient have been historically deployed within US popular culture and politics to support US moral superiority over Russia, as William shows in her analysis of American culture and US foreign policy between 1991 and 2003 Imagining Russia: Making Feminist Sense of American Nationalism in U.S.-Russian Relations. While Russia was mostly presented as physically ill in William’s examples, newer cultural productions such as the comic issues discussed here signify Russia as PTSD patient.Footnote1 This transformation corresponds to the political climate between Russia and the US: during the 1990s the metaphor of the ill patient was used to legitimate US development aid to Russia, while holding on to the narrative of ‘communist totalitarianism’ as evil sickness and US interventions as medicine.

While the notion of ‘communism as illness metaphor’ (Williams Citation2012, 62) faded, the more general idea that Russia is suffering from something stuck. As the country’s economy stability and growing world power rendered obsolete the US self-conception as Russia’s benevolent supporter and doctor, American cultural productions filled the empty signifier, which indicated that Russia is suffering from something dangerous, with the notion of Russian trauma. The shift from illness and physical wounds to trauma and mental disability emphasises the threat of the Russian condition. As PTSD does not necessarily show any bodily signs or symptoms, any figure can become associated with it, even the sexualised, beautiful, very able-bodied, cunning femme fatale in the dress of a princess or ballerina.

Trauma and the Russian ballerina

The representation of the Widow as traumatised ballerina deserves further investigation. These ballerina images are mostly very dominant in individual issues, taking up an entire page (Cornell et. al Citation2010b, 6; Waid, Samnee, and Wilson Citation2016, 57) or are featured on the cover (Morgan, Parlov, and Sienkiewicz Citation2005a). The mysterious and intriguing ballerina is, as already indicated, another adaptation of the femme fatale and signifies the Widow’s Russian heritage. Russian ballet is not only world famous but also has a special place in American popular culture. The Nutcracker, originally choreographed by Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov to the music of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, continues to be one of the most successful ballets performed by countless US ballet companies during every Christmas season (Fisher Citation2003). Individual Russian ballerinas such as Anna Pavlova, initial member of the Ballet Russes, who toured North America with her enormously famous dying swan performance (Fisher Citation2012), or Natalia Romanovna Makarova, who defected in 1970 to set standards for generations of dancers in the West (Clarke et al. Citation1981, 210), have a special place in American cultural memory. Yet, there is another, deeper meaning to the ballerina. Unlike most other performance art forms, the history of Russian ballet is tightly connected to the military, and the royal court (Homans Citation2010, 621–728). Over the course of several centuries, ballet became institutionalised within the Russian royal court. Moreover, it did not only imitate military formations, soldiers and serfs of the royal court also performed it. It was arguably not simply an art form, but had additionally the function to demonstrate both military and cultural sophistication, skills and power. While the direct connection to military training and representation might have been lost over the course of the twentieth century, the idea that Russian ballet training resembles the rigour and discipline of a military education, demanding subjugation of the dancer to the rules of ballet, rather than expressing artistic individuality, definitely survived within American cultural knowledge.

Accordingly, the history of the Widow as being trained as a Russian ballerina conjures up notions of rigorous disciplining, extreme physical and mental training from an early age on. Such a hard training alone can be interpreted as traumatising, referring once again to the Widow’s Russian past as structured through trauma.

This connection between Russia, the ballerina figure and trauma is frequently supported by the visual elements as well as colouring in the individual issues. The cover of the Black Widow issue four from 2005 (Morgan, Parlov, and Sienkiewicz Citation2005a), for example, is a collage that features a young Widow as an exquisitely posed ballerina in its centre. The background forms a contemporary half-body sized image of the Widow, wearing her signature black catsuit and holding a smoking gun. In the left upper corner, there is a Russian Orthodox Church that looks like the Christ the Saviour Cathedral in Moscow; in the left lower corner there is a group of scientists in white coats. The ballerina refers to the Widow’s past and already indicates that the Widow will go back to Moscow, signified through the Church, to confront her past. The contrast between the ballerina and the fighter, dressed in black latex, is very significant. While the former seems to refer to her history as ‘serf’ of the Russian military, the latter seems to suggest that she is now emancipated and out to avenge herself upon the bad Russians.

The scientists in white coats presage that the reader will learn how the Widow had been traumatised and violently manipulated by the Russian or Soviet forces. A looming danger is signified through the colouring of the entire issue in deep blue, grey and black. As an additional reminder that Russia is the Widow’s location, some images integrate symbols such as hammer and sickle that refer back to the country’s traumatising Soviet history (Morgan, Parlov, and Sienkiewicz Citation2005a, 3). The suspense and mystery, that the colours and symbols of danger indicate, culminate in issue six from 2005. In this issue, it is revealed that the Widow’s identity as a beautiful Russian ballerina, who lost her beloved husband and became a spy, was false, implanted into her brain through scientific manipulation. This realisation ‘completely shattered [the Widow’s] past, present, and possibly, her future’ (Morgan, Parlov, and Sienkiewicz Citation2005b, 1).

The S.H.I.E.L.D.’s Most Wanted series (Waid, Samnee, and Wilson Citation2016) similarly uses the ballerina images to signify the Widow’s Russian traumatising past as one of multiple superweapon trainees in the Red Room and contrasts it with her current role as fighter and crusader for American values. In the series, the ballerina is a generic figure that does not carry any individual aspects; she is the product of traumatising processes of ballet training and military weaponising. The cover of issue three visualises the toll, that the traumatic experience took, most explicitly: It shows the Widow on her knees, her face contorted with pain, and her arms in the tight grip of black faceless paper cut girls, lining up in two seemingly endless rows left and right to her. The multiple identical girls are frightening in their uniformity and dominance. The absence of individual difference suggests that the Red Room training facility dehumanised the girls to form them into merciless weapons. The colouring of the series in dark grey, blue and black enhances the impression of a looming danger. It is contrasted with a lot of bright red, which refers, as mentioned above, to the colours of the black widow spider and to the Widow’s communist past.

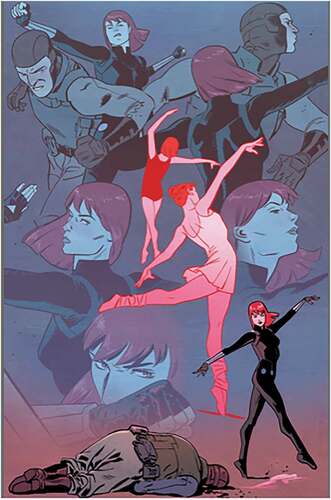

Multiplicity and uniformity are recurring themes within the series. The Widow herself is multiplied in the issue through scenes of her past as a child in the Red Room. The issue itself contains many fighting scenes, where the Widow battles the soldiers of the Red Room in the present. Between these combat scenes memories of the Widow as child appear (Waid, Samnee, and Wilson Citation2016, 51–52). The structuring and sequence of the scenes suggest that the Widow is not only fighting the current and immediate threat but also confronting her past trauma. This reading is further supported by a full-page fighting scene on page 12 of issue 3 (Waid, Samnee, and Wilson Citation2016, 57). While most of the memories are neatly separated from the present through the frames, there past and present intertwine.

‘Fighting scene.’ (Waid, Samnee, and Wilson Citation2016, 57).

The image shows eight versions of the Widow from different perspectives either in a fight with her enemy or as her old self as a ballerina, in a white tutu and in a red leotard. The stylised ballet poses are mirrored by the fighting poses. There is no text.

If the frames are understood with Chute ‘as boxes of time [that] present a narrative’ (Chute Citation2010, 5), the absence of the gutter in page 12 can be understood as a glimpse into the Widow’s head where time and space, memory and present overlap. Among the different versions of the past and present Widow, the two figures of the ballerina dominate. A similar visual strategy is used in issue two of Deadly Origins from 2010: the gutter is equally absent, the images of past and present interlace (Cornell et. al Citation2010b, 6–7). On page six a male and a female dancer occupy the middle of the page, taking up most of the space. Yet, they are dominated by shadows and their faces are turned halfway. The female ballerina is multiplied again, this time in a scene, where several ballerinas warm-up or train together at the right edge of the page. This scene is peripheral, almost like a peek through a keyhole. In between and around the dancing figures contradictory memories intertwine: Russian civilians march next to golden elements at the Bolshoi theatre; in the left corner, a Cathedral with multiple colourful towers and onion-shaped cupolas appears. Scenes of military training and military operations alternate on the following page. The reader takes a look into the Widow’s head, visually experiencing her state of confusion and trauma, acquired due to the abusive training and the brainwashing of her youth. The Widow and, together with her, the reader, are in a kind of epistemological crisis: text indicates that some narratives of the past are real and some artificially implanted, but it is unclear which one is which (Cornell et. al Citation2010b, 6–7). Moreover, in both scenarios the Widow had to suffer, no matter if as one of 28 beautifully graceful ballerinas in a poverty-stricken Russian Bolshoi theatre (Cornell et. al Citation2010b, 6) or as part of the 28 military trainees in the Red Room (Cornell et. al Citation2010b, 7).

Even more pronounced appears the traumatic deconstruction of the Widow’s identity in issue 103 of Tales of Suspense (Rosenberg, Foreman, and Rosenberg Citation2018a). There, her uniqueness and individuality are seriously questioned through the visual multiplication of the ballerina as weapons. Previously, the Widow had been killed by an evil version of Captain America in Secret Empire issue seven (Spencer, Sorrentino, and Reis Citation2017), sacrificing herself for the greater good.Footnote2 In Tales of Suspense issue 103 (Rosenberg, Foreman, and Rosenberg Citation2018a), however, North America has been reinstalled as morally superior and newly juxtaposed to the enemy, Russia. Bad Russian forces have rebuilt the Red Room training facilities, reproducing military super spies through ballet training among other techniques. They recovered the Widow’s mind from her dead body and found a way to not only store her memories but also implant them into one of multiple Widow clones. The depiction of cloning, although it looks very differently on first sight, goes back to the depiction of Soviet soldiers in their brown uniformity in earlier comics (e.g. Lee, Korok, and Heck Citation1964, 8, 10). Both examples illustrate the disregard of the individual and the weaponising of the masses.

The experiments that the Widow discovers in the Red Room pose questions about what it means to be human. The Russians have not only cloned Romanova but also all other Widows of the original Soviet Red Room. These empty bodies are now waiting to serve as backup shells to be implanted with a mind. The image, where the Widow confronts her clones, is coloured in shades of green, depicting a laboratory with several glass barrels filled with liquid and growing bodies (Rosenberg, Foreman, and Rosenberg Citation2018a, 9).

‘Confrontation with her clones.’ (Rosenberg, Foreman, and Rosenberg Citation2018a, 9).

The colouring and the depiction of the multiple identical bodies in different stages of completion are frightening. The green colour suggests toxicity, as does the shape of a barrel. The most unsettling is, however, the multiplicity of one and the same body as such. The disturbing quality of identical duplication is mirrored further in pictures where groups of identical child versions of the Widow are trained in ballet dancing and fighting (Rosenberg, Foreman, and Rosenberg Citation2018a, 11, Citation2018b, 4, 5, 11, 16, 17). Their depiction is not entirely logical since the clones in the barrels are growing into the forms of adult women.

The cloning of children, however, visualises the Russians’ bad ethics, disregard of the individual human being and the dangers of biotechnology even further. It is another story element that leads the reader to the ethical conclusion of Issue 104, which is that the individual mind is the essence of what makes a human human. Moreover, an assemblage of memories is what forms the mind and individual humanity: the concrete memories in their entirety make up the human personality. Most importantly, only such an individual personality can be good.

Trauma embodiment and politics of location

The idea that the Red Room is not just a training facility, but also a biochemical laboratory, goes back to volume three of the Black Widow comics (Morgan, Parlov, and Sienkiewicz Citation2005b, 1). There the Widow’s brain and body become manipulated to exceed human physical abilities and slow her ageing process, through cruel and traumatising means.

The aspects of brainwashing and biochemical enhancement further connect ideas around memory, trauma and Russian heritage with the Widow’s body. Brainwashing clearly signifies the mental injury of the traumatic event almost in a plastic or material sense, since it is a procedure that temporarily breaks the human will by suppressing individual memories as well as the memories of the violent interference of the injury itself and makes the mind permeable for manipulation. This idea draws on traditional Cold War discourses and the rivalry between Soviet Russia and the USA. The addition of more recent forms of genetic manipulation interlinks the perfectly hourglass-shaped superbody of the Widow and the Soviet legacy and contemporary Russia. Significantly, part of these alterations was her sterilisation. These drastic interventions into her female physique and violation of her bodily sovereignty foreground her body additionally as traumatised body.

Through the confrontation with her trauma, the Widow experiences an ‘injury and pain [that] temporarily dislocate [her] from the frameworks of locality (and by extension, ideology)’ (Jelača Citation2016, 14). She literally goes back to Russia, the place of the injury. Multiple signifiers, images, figures and metaphors address Russia explicitly as the location and inducer of her trauma. The Red Room is a metaphor for communist Russia, and the information that it is somewhere on the territory of current Russia (Waid, Samnee, and Wilson Citation2016) suggests the successor country wants to reinstate a version of Soviet authoritarianism.

The Red Room in this duality as ballet school and military academy (Cornell et al. Citation2010b, Waid, Samnee, and Wilson Citation2016; Rosenberg, Foreman, and Rosenberg Citation2018a, Citation2018b) is a reference to the historic Cold War culture that manifested not only in an arms race between Russia and the USA but also in a competition about who has the ‘better’ culture. Thus, several historic discourses intersect within the ballerina body of the Widow: the struggle for world power during the Cold War and the loss thereof during the so-called transition period, old and new structures of militarisation and biological warfare, etc. The amalgamation of these and other historic Russian trauma narratives, for example, the previously described annihilation of the Romanovs, the civil war, or the Stalin terror, not only construct the Widow as a figure with PTSD but create the impression that she is a stand-in for the country of Russia as such – a country with PTSD.

This idea of Russia as place and figure of trauma is particularly pronounced in issue 103 of Tales of Suspense (Rosenberg, Foreman, and Rosenberg Citation2018a). Trauma has a special place in this discussion. The Widow goes through the traumatising realisation that she has been created artificially in an unethical way for an evil purpose and that she is not unique, at least not physically. Interestingly, in the first view panels of issue 103, it is explained that the Widow recovers from the great trauma of being killed by her former friend and temporarily corrupted Captain America.

This idea of a dangerous America is quickly abandoned by the issue. Moreover, the focus on Russia as female and traumatised figure embodied through the Widow is supported by yet another female trauma figure: a bear. Historically used to signify Russia, the bear can be read as yet another female embodiment of Russia. She supports the idea that Romanova’s story is not only her individual one but also one about Russia. Her name Ursa Major is a star constellation in the northern sky and means ‘greater she-bear.’ She is a military major and Russian patriot that has grown to despise the politics of the Red Room. She is also a guiding star for the Widow, a kind of mother figure (‘Mother Russia’) supporting her in her mission to defeat the Red Room. Understood as stand-in for Russia, major additionally refers to the impressive size of the country.

The microcosm of the Red Room stands in for Russia as country and location, where bad forces have taken over and want to reinstall a rule developed during the worst of Soviet times. Alexander Cady, a figure high up in the Red Room hierarchy, explains to the Widow that ‘there was a dark time […], but thankfully, things have turned around again. We look forward by looking to our glorious past’ (Rosenberg, Foreman, and Rosenberg Citation2018a, 11). This Soviet past is further referred to by the Russians calling each other comrades, some of them wearing Soviet uniforms, the red colour of the Red Room, and the child ballerinas, the next generation of Widows/military super weapons. This new Russia, clearly, has to be freed and brought back on the track of Americanisation in terms of morals and values.

Tales of Suspense issue 103 and 104 make a strong statement about the New Cold War opponent Russia. The bear secretly helps the Widow to keep all her memories during her resurrection, especially those of her status as American Avenger and agent, because these memories, it is implied, make her exceptional and good. Applying this argument to the country itself leads to a conclusion that only an alliance with America and its values can save Russia. This struggle is visualised not only through the scenes that show the Widow fighting but also and most impressively in the image of the big brown bear and multiple tiny ballerinas – that have been recently ideologically flipped to the good side – in white tutus and leotards fighting a uniform mass of bad soldiers in black riot gear (Rosenberg, Foreman, and Rosenberg Citation2018b, 16).

The decisive battle in Tales of Suspense issue 104 (Rosenberg, Foreman, and Rosenberg Citation2018b, 14) is, however, not against the men in riot uniforms. It is the Widow’s fight against the cloned versions of herself.

‘Killing her own clones.’ (Rosenberg, Foreman, and Rosenberg Citation2018b, 14).

The images where the Widow shoots copies of herself are brutal. She shoots them from relatively close proximity, catapulting their bodies away from her in hunched angles and with faces distorted in pain. The long flying red hair of the multiple Widows indicates the force of the bullets, the entire room is lit up in bright orange and red by the little explosions from the weapons. The clones are almost indistinguishable from the Widow. Only their tight white body suits set them apart from the original Widow, who wears a military, but non-combat uniform. Symbolically, the scene is a fight against Russia, for Russia. The Widow, the little ballerinas and the bear defeat the Red Room powers, while her two American ex-lovers, the Hawkeye and the Winter Soldier, merely assist.

The gender distinction of Tales of Suspense issue 103 and 104 is very interesting. While the male characters, especially the blond American Clint/the Hawkeye, are very emotional, motivated by their love and care for the Widow, she is portrayed as a cool strategic thinker, who does not let her emotions get in the way of control. Such a portrayal of female agency can be interpreted as feminist tendency, complying with liberal ideas of female empowerment and equality. Yet, the Widow and all other strong women have heteronormative, overtly sexualised female bodies. They conform to a heteronormative male gaze: their wavy long hair seems no hindrance in combat and their bodies are always pressed into tight body suits, leotards or skirts that highlight their feminine curves. Additionally, the Widow’s readiness to kill the cloned women in contrast to the American Clint’s hesitation for ethical reasons (Rosenberg, Foreman, and Rosenberg Citation2018b, 14) can not only be interpreted as female agency to take the tough call in a feminist sense but also as a deferral of murder to a non-American body.

Conclusion

The comic heroine Black Widow has been linked historically to Cold War ideas about the relationship between the USA and Russia, Western moral superiority and Russia danger. The series Black Widow–Deadly Origins (Cornell et al. 2010), and Black Widow–S.H.I.E.L.D.’s Most Wanted (Waid, Samnee, and Wilson Citation2016) as well as the issues 103 and 104 of Tales of Suspense (Rosenberg, Foreman, and Rosenberg Citation2018a, Citation2018b), continue this trend by constructing the Widow through the old Russian tropes commonly known within American popular culture such as the ballerina and the (trauma) patient. The ballerina stands in for the cultural heritage of Russia, its sophistication and sexualised exoticism. On closer inspection, however, it also points to discipline and obedience to power (communist) anti-individualism and the weaponising of bodies. Especially in their mass-appearance, ballerinas are a metaphor for Russia’s past that offends American ideas of individuality. This danger is enhanced through the false innocence of the child ballerinas, presented either as the Widow’s memories or her clones.

The aspect of cloning and other forms of multiplication connect the ballerinas to the second historic Russia trope, the (PTSD) patient. The traumas connected to the Widow are multiple. She has been biochemically manipulated and brainwashed; had to go through a harsh training as ballerina and as military special operative; has been betrayed and lied to, and, finally, killed by a friend (Captain America). Her trauma memories are brought forward both by the text and by the specific deployment of the comic form on a visual level: through the absence of grids, the identical multiplication of the figures, etc.

Moreover, the Widow embodies traumas – traumas specifically connected to Russia and its culture. Through her figure, the comics address the legacy of the Soviet communist rule as collective trauma, to reaffirm US neoliberal individualism and moral superiority. The comic visualises communist mass conformity as unethical through narratives involving biotechnology such as cloning. It presents identical duplicity or multiplicity to reject communism (and what it imagines to be its afterlife today) quite literally, as inhumane human experiments and cause for trauma. Although the Russian trauma is a collective cultural trauma, it can only be resolved through the Widow’s individual agency and heroism.

Projected onto the figure and body of the Widow, the trauma has two effects. First, it others the Widow as Russian. Second, it uses her trauma as motivator for the narrative that directs the attention away from mental health issues. Instead of a struggle for mental health and happiness, her individualised traumas become the reason to fight for the right values, which are always signified as US values. This way Russian trauma becomes a site for the negotiation of American values and offers an outside challenge that can be resolved with a happy ending. The gender dimension of the Widow comics confirms ideas about Russia as sexualised Other to the male American gaze and thereby contradicts the feminist agency that a powerful female superheroine otherwise presents.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Katharina Wiedlack

Katharina Wiedlack is FWF Senior Post-Doc Researcher at the Department of English and American Studies, University of Vienna. Her research fields are primarily American Cultural and Literature, American-Russian relations, queer and feminist theory, popular culture, postsocialist, decolonial and dis/ability studies. Her first book “Queer-Feminist Punk: An Anti-Social” was published in 2015, by the feminist publisher Zaglossus. Currently, she is working on two independent research projects. Her FWF Elise Richter project “Rivals of the Past, Children of the Future” focuses on the discursive construction of Russia within Western thought between the time of the American purchase of Alaska to the beginning of the Cold War. Her second FWF project is an arts-based research project and collaboration with Masha Godovannaya, and Ruth Jenrbekova from the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts. It focuses on questions of in/visibility, queer ways of living, community building, and archiving within the post-Soviet space.

Info about the FWF Elise Richter project and CV: http://katharinawiedlack.com/

PEEK project page: https://magic-closet.univie.ac.at/

Notes

1. Sean Guillory, for example, argues that Russia is suffering from PTSD induced by the dissolution of the Soviet empire, and that Russia’s the current political actions are ‘a reaction to a trauma experienced by millions’ (Guillory Citation2014).

2. The story of a corrupted Captain America fighting on the side of evil was unpopular among many fans (Shiach Citation2017a) and retailers (Shiach Citation2017b), who prefer a version of the US and their representative Captain America that is unambiguously morally good fighting not an inner enemy, but an outer foreign one.

References

- Alaniz, J. 2014. Death, Disability, and the Superhero: The Silver Age and Beyond. Jackson: Univ. Press of Mississippi.

- Bukatman, S. 2003. Matters of Gravity: Special Effects and Supermen in the 20th Century. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Chute, H. 2010. Graphic Women: Life Narrative & Contemporary Comics. New York: Columbia Univ. Press.

- Clarke, Mary and Clement Crisp. 1981. The History of Dance. London: Orbit.

- Cornell, P., T. Raney, S. Hanna, M. Milla, and J. P. Lean. 2010a. Black Widow-Deadly Origins #1. (January).New York: Marvel Publishing.

- Cornell, P., T. Raney, S. Hanna, M. Milla, and J. P. Lean. 2010b. Black Widow-Deadly Origins #2. (February). New York: Marvel Publishing.

- Cornell, P., T. Raney, S. Hanna, M. Milla, and J. P. Lean. 2010c. Black Widow-Deadly Origins #3. (March). New York: Marvel Publishing.

- Cornell, P., T. Raney, S. Hanna, M. Milla, and J. P. Lean. 2010d. Black Widow-Deadly Origins #4. (April). New York: Marvel Publishing.

- Costello, M. J. 2009. Secret Identity Crisis: Comic Books and the Unmasking of Cold War America. New York and London: Continuum.

- Doane, M. A. 1991. Femmes Fatales: Feminism, Film Theory, Psychoanalysis. New York and London: Routledge.

- Fisher, J. 2003. Nutcracker Nation: How and Old World Ballet Became a Christmas Tradition in the New World. New Haven/London: Yale Univ. Press.

- Fisher, J. 2012. “The Swan Brand: Reframing the Legacy of Anna Pavlova.” Dance Research Journal 44 (1): 51–67. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0149767711000374.

- Glajar, V., and D. Radulescu. 2004. “Introduction.” In Vampirettes, Wretches and Amazons: Western Representations of East European Women, edited by V. Glajar and D. Radulescu, 1–11. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Guillory, S. 2014. “Is Russia Suffering From Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder?” New Republican, April 24. https://newrepublic.com/article/117493/russia-suffering-post-traumatic-stress-disorder

- Heller, S., and M. Barson. 2001. Red Scared!: The Commie Menace in Propaganda and Popular Culture. San Francisco: Chronicle Books.

- Homans, J. 2010. Apollo’s Angels: A History of Ballet. New York: Random House.

- Jelača, D. 2016. Dislocated Screen Memory: Narrating Trauma in Post-Yugoslav Cinema. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lee, S., G. Conway, G. Colan, T. Palmer, and J. Costa. 1972. Daredevil #88. New York: Marvel Comic Group.

- Lee, S., N. Korok, and D. Heck. 1964. Tales of Suspense #52. New York: Marvel Comic Group.

- Macchio, R., and G. Pérez. 1983. Marvel Fanfare 1 #10. New York: Marvel Comic Group.

- Morgan, R., G. Parlov, and B. Sienkiewicz. 2005a. Black Widow 3 #4. New York: Marvel Publishing.

- Morgan, R., G. Parlov, and B. Sienkiewicz. 2005b. Black Widow 3 #6. New York: Marvel Publishing.

- Roberts, G. 2006. Stalin’s Wars: From World War to Cold War, 1939–1953. New Haven, CT/London: Yale University Press.

- Roman, Z., and R. Lizardi. 2019. “‘If She Be Worthy’: The Illusion of Change in American Superhero Comics.” Inks: The Journal of the Comics Studies Society 2 (1): 18–37. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/ink.2018.0002.

- Rosenberg, M., T. Foreman, and R. Rosenberg. 2018a. Tales of Suspense #103. New York: Marvel Publishing.

- Rosenberg, M., T. Foreman, and R. Rosenberg. 2018b. Tales of Suspense #104. New York: Marvel Publishing.

- Shiach, K. 2017a. “Marvel’s Controversial Secret Empire Event Is Over. Was It Worth It?” Polygon, September 14. https://www.polygon.com/comics/2017/9/14/16307304/secret-empire-ending-explained

- Shiach, K. 2017b. “How Are Retailers Reacting To Secret Empire & Marvel’s Hydra Takeover?” CBR, April 26. https://www.cbr.com/retailer-reaction-secret-empire-hydra-takeover-marketing/

- Spencer, N., A. Sorrentino, and R. Reis. 2017. Secret Empire #7. New York: Marvel Publishing.

- Waid, M., C. Samnee, and M. Wilson. 2016. Black Widow–S.H.I.E.L.D.’s Most Wanted. Collecting #1-#6 New York: Marvel Publishing.

- Williams, K. 2012. Imagining Russia: Making Feminist Sense of American Nationalism in U.S.-Russian Relations. Albany: State Univ. of New York Press.