ABSTRACT

To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee, long considered an American classic and one of the most beloved books for adolescents, has raised much controversy since its publication in 1960. Its adaptation as a graphic novel by Fordham and Lee offers a reinterpretation of the story. It highlights the racial tensions and social inequality, and it shows the consequences of isolation and marginalisation of characters along the lines of race, gender and class, but it does so through the lens of entrapment. These motifs are shown in the panel structure, the choice of colours and the framing of individual panels. The refreshed version better fits the changed sociopolitical circumstances and it better reflects the expectations of a new generation of readers, reaching for the story over sixty years later.

To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee, long considered an American classic and one of the most beloved books for adolescents, has raised much controversy since its publication in 1960. It has been acknowledged as one of the most important novels of the 20th century, and its author was presented with the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2007. In Citation2021, The New York Times announced it the best book in 125 years. On the other hand, it faced considerable backlash, too: it has been accused of promoting the ‘white saviour’ motif (Meyer Citation2013, 37), of ignoring the real problem of the South while focusing on largely irrelevant aspects (Shaw-Thornburg Citation2010, 114), or of using ‘questionable and immoral language’ (Seligman Citation2010, X), overusing racial slurs and other words that are considered offensive. Moreover, many readers feel misrepresented by the image of the carefree childhood it offers (Shaw-Thornburg Citation2010, 114), and many others strongly object to the themes of racism and profanity that are commonplace in the story. For these reasons, its value has been questioned many times, and the novel itself was reported to be one of the most frequently challenged books of all times, according to the American Library Association (Citation2013). Could the narrative defend itself 60 years after the original publication? Could a new adaptation shed a new light on the classic?

Lee’s novel was published in 1960, in the wake of the Civil Rights Movement, but it is set in the 1930s, when the Scottsboro Boys’ case divided the country and started heated discussions on racism and justice. Lee shows the ugly face of the Jim Crow South by portraying the divided and unequal small-town community in which people do not abstain from using racial epithets and applying violence to have their way. In the 21st century, much has changed in this respect, yet the Jim Crow past still casts a long shadow. Racial tensions and inequality have not been overcome; on the contrary, they can still be seen in towns and cities, in the disproportionate number of African American prisoners, and the uneven access to education and well-paid jobs. Two generations after the publication of Lee’s novel, the questions raised there are as relevant as ever.

The adaptation of Lee’s work in the graphic novel by Fordham and Lee, published in Citation2018, addresses these questions anew in the form that is arguably more accessible for younger audiences. It puts racial tensions and social inequality in the limelight again to show where they may lead if not stopped before hatred escalates. It focuses on the theme of alienating ‘the other’ by society: a black person, a woman too poor or too independent to fit the ideal of the Southern lady, a self-reliant girl, and an estranged young man locked up in his house. Though central to the main conflict, all such characters are strangely marginalised in the source text: nothing is made known about them beyond what is indispensable to explain the events, and once they fulfill their roles, they vanish. Fordham’s adaptation gives voice to these characters, puts them in the spotlight for a moment long enough to be acknowledged by the readers, and thus shifts the focus of the story. By foregrounding the motifs of entrapment and isolation that they all experience, the graphic novel offers a new interpretation of the story and addresses the questions that are still relevant today.

Being an adaptation, Fordham’s version is read with Lee’s original novel in mind. As Linda Hutcheon (Citation2006, 8) points out, adaptations are ‘palimpsests through our memory of other works that resonate through repetition with variation.’ As such, their interpretation by the reader involves intertextuality, i.e. understanding them through the lens of other works, as well as the broader context. Therefore, such works are context-dependent (Hutcheon Citation2006, 142; Elliott Citation2014), as they combine the expectations of the contemporary/receiving audience with the original background of the source text. If the two contexts are divergent, as is the case of To Kill a Mockingbird, the modern rereading may differ from the reality of the original author, and the text may be interpreted differently. As Cutchins, Meeks, and Eckart (Citation2018, chapter 26) emphasise, though, the experience of the readers is the main focus of the adaptation, and if they reinterpret the story because of the changed circumstances, a unique dialogue between the two versions and the two time periods can be observed.

Fordham’s adaptation of the 1960 story into a graphic novel is a significant choice because it entails certain features characteristic for the medium that were absent from the traditional narrative. It fits into the trend discussed by Jenkins (Citation2020, 5) and Baetens and Frey (Citation2015, 5) of experimenting with the content and the narrative techniques, as well as adding new subjects such as social justice, thus broadening the scope of the medium. Descending from the comix publications of the 1960s and 1970s (Hatfield Citation2009, 4), through the important changes in the reception of the medium since then, graphic novels have become an important voice in the discussion of pressing social issues, readily embraced by younger audiences, who arguably are more willing to choose visual storytelling over traditional textual one. Hence, the comic adaptation may be more appealing and therefore easier to interpret for the 21st century readers, both the ones approaching the story for the first time and revisiting it after some time.

Fordham’s work does not simply ‘seek to reinvent Harper Lee’s story and characters,’ though, as he admits in Illustrator’s note appended to the graphic novel. He uses the lines taken directly from the source text, although abbreviated to fit the requirements of the medium. However, his choice of what to keep and what to omit is crucial, as it does change the interpretation of some scenes and the depiction of the characters involved. For example, in Lee’s novel Atticus seems to avoid the word ‘racism’ and uses the word ‘disease’ or ‘something’/‘it’ instead. When he comments on the jury’s verdict, he says, ‘you saw something come between them and reason. You saw the same thing that night in front of the jail’ (Mockingbird Citation[1960] 2020, 243). He is more straightforward in the graphic novel, though. In the same scene, he explains, ‘when it’s a white man’s word against a black man’s, the white man always wins’ (Fordham and Lee Citation2018, 237). Even though it is a direct quote from the source novel, the message is not diluted by the indefinite words (‘the thing’), so it reverberates much stronger.

Moreover, the language that has been a source of contention in Lee’s novel, especially the frequent use of the offensive N-word, is not altered here because, as Fordham and Lee (Citation2018) points out in the note, ‘its dehumanising power and the ease with which it was used is central to understanding the themes of the novel.’ By quoting it in his version without offering any additional comment for example in a footnote, he introduces a jarring accent that inevitably catches the reader’s attention and makes them consider racial issues more closely.

In general, people in Maycomb are caught up in a web of social expectations. They need to comply, otherwise they will be ostracised. Even though racial and gender demands are arbitrary, they are closely observed, and Tom’s case is an arena where such tensions are played to the fullest. Such a social environment severely limits every character’s freedom. Women in particular are supposed to comply, otherwise they will be excluded, and not many of them can afford living by their own rules. Even Miss Maudie, well-known for working in the garden in male attire, changes in the afternoon as she sits on the porch, watching others go by (Mockingbird Citation[1960] 2020, 47). Therefore, everyone is trapped by the circumstances. Yet, the motifs of entrapment and isolation may escape the reader’s attention in the original novel, as they are overshadowed by other issues. The focus is shifted in Fordham’s adaptation, where imprisonment and ensuing loneliness are foregrounded in a number of ways. Such isolation is suffered the most by the weakest members of Maycomb community (the black, the poor, women, children), but as these themes are highlighted in the graphic novel, the reader has a chance to observe them from a different perspective, that is from the point of view of the victims. Even though the scenes are often focalised by an outsider standing behind a fence (hence, by a member of the privileged majority), the close-up on the victim’s face, or the composition inside the panel, put them in a different light and make the reader consider the side of the character that has been trapped by the circumstances.

Entrapment, often resulting in an isolation of a character, seems to be the main focus of the graphic novel. It is implied in a number of ways: in the foregrounding of fences and physical barriers to symbolise the characters’ imprisonment and alienation; in the panel structure (gridding and size); in framing, and in colour. They all have a strong impact on the perception of the story, as they show how the comic brings those motifs to the forefront. Moreover, it reflects the division of the community along the lines of race, gender and class differences, and it tackles the issue of the dignity and agency of people that stems from it. It points to the general pattern of exclusion of ‘the other’ who supposedly threatens the established order.

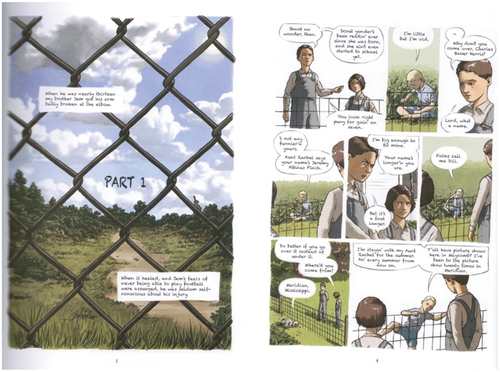

It is introduced in the first panel, where it is shown literally, by means of fences dividing the area and keeping, or even trapping, people on one side. It is the main element dominating the first image, which opens the story (Fordham and Lee Citation2018, 1; on the left). It separates the open space full of greenery, with a wide path leading to freedom, serene sky, and peaceful landscape, from the place where the story is set and where the reader is positioned together with the characters. The metal grid in the foreground prevents anyone from trespassing and it keeps everyone locked in, with no way out. It implies that the story is contained inside the fence – within this society, in this town – and no escape is possible, as there is no gate provided. The two inscriptions introducing the story are also placed inside the fence, stuck onto the grid. As they additionally frame the story by proleptically referring to the dramatic events that are going to happen in the last part of the novel, they enclose the narrative and position it still deeper inside the physical and mental boundaries that overshadow the first image.

The motif of the metal grid stopping a person from moving around freely is then repeated in the scene in which the children meet Dill for the first time (Fordham and Lee Citation2018, 3–4; on the right). The three characters are separated by the metal barrier and even though they can talk easily, Dill cannot join Scout and Jem as he has considerable difficulty getting across. Being rather small for his age, he is unable to climb under or over it for a while, and his struggle is shown in two consecutive panels, larger than the other panels on this page, hence focusing the reader’s attention more effectively. Furthermore, picket fences dominate the landscape of Maycomb and they divide the town into a network of small plots, with an intricate maze of streets closing the area (Fordham and Lee Citation2018, 15, 41, et al.). Such a fence, additionally protected by barbed wire, becomes a barrier stopping Jem from escaping the Radley estate (Fordham and Lee Citation2018, 66) – he must leave his pants behind to save himself from getting shot by the owner of the place.

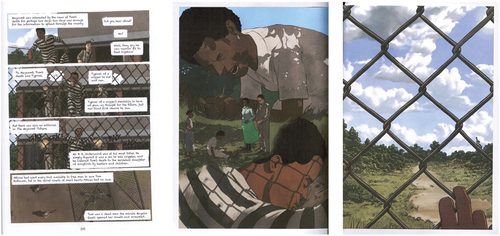

A metal fence returns in the key scene of the second half of the novel, namely in Tom Robinson’s futile escape attempt and death (Fordham and Lee Citation2018, 245; on the left). His dramatic run for his life is shown from the outside, from a distance, presumably by a member of the privileged majority unable to feel empathy for a black prisoner. The grid is foregrounded in the middle panels. It serves as a physical boundary, keeping the reader/onlooker safe while containing the prisoners and preventing them from running free. In the bottom panel, the fence additionally casts a shadow on the dead body, thus doubling the protection and the separation. This physical distance is further reinforced by the impersonal comments added to each panel, of the people of Maycomb gossiping about ‘Tom’s death for perhaps two days’ (Fordham and Lee Citation2018,245) and observing contemptuously that it is ‘typical’ for African Americans ‘to have no plan, no thought for the future’ (245). Tom has no say here, he utters no words, and no one is interested in hearing his motivation and his story.

Most pointedly, the scene is closed with a remark, ‘Tom was a dead man the minute Mayella Ewell opened her mouth and screamed’ (245). It highlights the central paradox that all African Americans faced at that time: no matter what he does, he is guilty because he has been accused of violating a white woman’s virtue. In Lee’s version, the comment was made by Scout, who finally understood the paradox and the futility of taking any action if it entails confronting a black man’s word with the white majority’s prejudice and conviction. In the comic version, it is a conclusion of an onlooker belonging to the privileged part of the community. When juxtaposed with the dead body lying in the shadow of the fence, the remark is all the more acute, and it emphasises the fact that racism kills, with bullets and with words.

Humanity and dignity are restored in the panel that follows, a full-page spread focusing on Helen’s wordless despair on hearing the news ( in the middle). Her isolation and immersion in her grief intertwines with the motif of entrapment as the shadow of the metal grid continuously falls on Tom’s still face, clearly showing who is responsible for this act – ‘the secret courts of men’s hearts’ (Fordham and Lee Citation2018, 245). However, it is the anguish and the agony in his wife’s face that takes the central position here. Her grief has no boundaries – there are no panels or gutters on the page, the whole space is filled with her emotions. The mindless or spiteful comments cannot reach her here in this moment.

The deeper meaning of this event for Helen and for the black community of Maycomb is shown in the panel that follows – a full-page spread that is an almost-exact copy of the opening image (Fordham and Lee Citation2018, 247; on the right). The same peaceful landscape is shown, yet this time the metal grid does not separate an unidentified subject. The black hand clasping the net signifies the entrapment and the ensuing isolation of Helen, rejected by the community during her husband’s trial and after his death. By extension, it also signifies the imprisonment of the African American part of Maycomb community, who can see the opportunity ahead but are prohibited from taking it, as they are incapacitated by their poverty and their social stance under the Jim Crow laws.

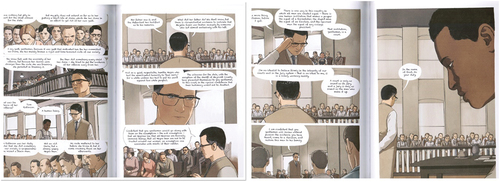

The motif of entrapment can also be observed in the panel structure and the general organisation of images throughout the graphic novel. Most pages are organised into a more or less regular grid, with panels separated by a clearly marked white gutter. Even though the actual number of panels differs from page to page, with frequent horizontal staggering and the inclusion of larger horizontal panels that take up the whole row, the structure looks rather consistent and predictable. A change in the pattern signifies an important moment in the story, such as the scene of Tom’s trial (Fordham and Lee Citation2018, 218–221, ).

Throughout the proceedings, and during Atticus’s final speech in particular, the panels are small and filled with text contained in large speech bubbles. As the talk continues, the panels grow bigger and there are more close-ups on the faces of the people gathered in the courtroom (Fordham and Lee Citation2018, 218–219, on the left). Four horizontal panels on p. 218 turn into three horizontal ones on pp. 219–220, only to culminate in a full-page spread close-up on the face of Tom and Atticus’s plea, ‘In the name of God, do your duty’ (Fordham and Lee Citation2018, 221, on the right). This gradual shift marks the last moments when Tom is officially innocent (until proven guilty), and therefore – theoretically – free. Image by image, he is slowly foregrounded and he becomes the centre of attention rather than being one of the crowd. Such a technique makes the scene more dramatic and intimate. Tom is shown as a suffering human being, deserving the reader’s undivided attention. The scene is shown from his perspective. As he is confronted with the all-white jury, he already knows the verdict, and so does the reader.

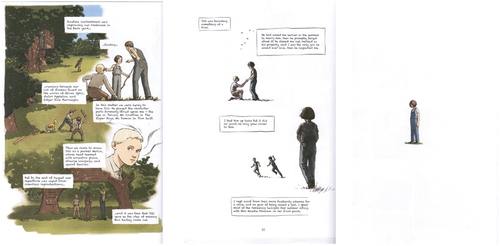

The alienation of ‘the other’ by the majority and the ensuing entrapment by the circumstances is also shared by other underprivileged groups, such as women and children – especially the ones who refuse to follow the unwritten code of conduct. It may also be signalled by a break in the regular panel structure, which inevitably draws the reader’s attention to the scene. For example, it is used to show Scout, Jem and Dill playing outdoors (Fordham and Lee Citation2018, 6, 52; ). In both cases the grid is substituted with loose images spread across a full page. The scenes are set during the summer of 1933 ( on the left) and of 1934 (in the middle). In the first scene, the children spend time together, very close-knit as a group, which is further implied by the green grass in the background of their activities, neatly unifying them in all their enterprises.

The situation changes a year later, though, when Scout feels neglected by the boys ( in the middle). This time, there is no common ground to unify the trio. Instead, there is a blank space separating them, most visibly distancing Scout from the boys, since Dill grew closer to Jem during that summer. The feeling of abandonment and loneliness culminates yet another year later, in the summer of 1935, when Scout is left stranded, a tiny figure in the middle of a full-page spread of blank space. Dill is absent from Maycomb this time, whereas Jem feels too mature to spend all his time with her. Scout’s growing isolation is brought about by social constraints – by being ‘the other’ not fitting general expectations of the community.

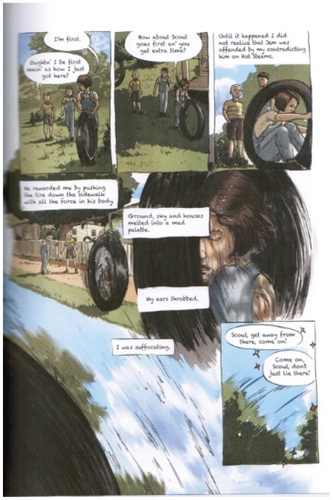

A break in the regular panel structure also marks a disruption of the established order, such as breaking out of the typical code of behaviour, a change in the status quo, or even violence. Again, a scene of the children playing together is such an example (Fordham and Lee Citation2018, 47; on the left). It starts with regular rectangular panels in the first row, which reflects the moment when they start the game and lay down the rules. However, as Scout is rolling in the tire, she loses control over the situation, so the grid is broken, the pictures fuse together, and the image is blurred to reflect her point of view and her dizziness. The scene is observed simultaneously from the inside (through her eyes) and from the outside (using the boys’ perspective). The panel inserted at the end, exactly in the place where it should be if the full 9-panel grid were used on this page, restores order and brings back reason into the scene as the boys urge Scout to get away from the Radleys’ backyard. Hence, the freedom from the tight frames imposed by societal expectations is only temporary. After the ride is over and Scout’s dizziness passes to the point that enables her to walk away, the grid reappears with the last panel. It signals the re-establishment of order.

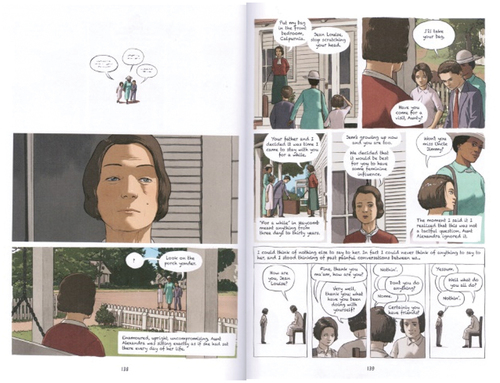

The significance of the panel structure may be further reinforced by the organisation and the size of the text. This can be observed in the scene of Aunt Alexandra’s arrival and her moving in with Atticus’s family (Fordham and Lee Citation2018, 138–141; ). Her presence entails changing Scout’s behaviour to be more ladylike, ensuring ‘some feminine influence’ (Fordham and Lee Citation2018, 139) over her, or, put simply, the end of her freedom and a form of entrapment for the tomboy she has always been. The gradual movement from freedom to oppression can be noticed on pp. 138–139 (), where the story development is accompanied by the changing design of the panels, from the image of the children with Calpurnia against empty space, not constrained by the panel frames, to an accumulation of small panels in the bottom row, packed with multiple speech bubbles. As the number of panels per row grows, so does the feeling of confinement.

However, Aunt Alexandra’s influence is less prevalent in the graphic novel than in the source text. In Lee’s version, after Atticus tells his family about Tom’s death and takes Calpurnia along to inform Helen about it, Scout changes. She helps serve tea to the guests, saying, ‘if Aunty could be a lady at a time like this, so could I’ (Mockingbird Citation[1960] 2020, 262). It is a very significant moment because it implies the girl’s transition from ‘the other’ to the majority, and her final acceptance of societal norms. This part of the scene is missing from the graphic novel, though (Fordham and Lee Citation2018, 244). After Atticus asks Calpurnia to accompany him, the scene breaks off and the details of Tom’s death follow. So, not only does Scout remain a tomboy, non-compliant with general societal expectations (next time she appears, she is walking to school to celebrate Halloween – Fordham and Lee Citation2018, 249), but also the spotlight is shifted to show the result of another character’s entrapment by his race and social position: the narrative moves to show Tom’s death at the hands of prison guards.

The framing of the image is as important as panel organisation in a graphic novel, and here this technique is mostly used to show or imply Boo Radley, who is another alienated and underprivileged character in this story. An emblem of imprisonment or entrapment in the novel, Boo is mostly defined as an absence – ‘a haint’ (Fordham and Lee Citation2018, 27) living in a mysterious house with tightly closed shutters, a flicker of light in the window (15 – in the middle), disembodied laughter coming from behind locked doors (Fordham and Lee Citation2018, 51), or the invisible hand that leaves small gifts for the children (41, 43, 74 – on the right) and offers a blanket on a cold night (87). If he is presented at all, it is as a silhouette in the darkness, shown from behind as he is looking out of a window (Fordham and Lee Citation2018, 7, 87; on the left). More frequently, though, his presence is only alluded in a peculiar type of framing, when the children find the items he left for them in the hollow of the tree. The framing suggests that Boo was observing Scout and Jem, using the tree as his only means of communication, his only window on the world. Significantly, once the hollow is cemented in, the perspective shifts and the tree can only be seen from the outside – the sole way of contact has been broken, and Boo is irrevocably trapped.

Called ‘a malevolent phantom’ (Fordham and Lee Citation2018, 7) by the children, Boo eventually saves their lives from Bob Ewell’s attack, and once that happens, he can finally be seen. He first appears on a double-page spread in a strange collage of body parts and close-ups that are mostly out of focus (Fordham and Lee Citation2018, 262–263; on the left). Even though the blur is used to emphasise the fact that Scout, the narrator, is crying, it is still one of the most irregular and therefore disconcerting images throughout the graphic novel. As such, it implies an equally disconcerting perception of Boo’s life both by Scout and by the rest of the community. Being a prisoner all his adult life, an absence in the life of Maycomb, he has essentially turned into a ghost: even his complexion is visibly paler than other people’s, and identical in hue with the wall (Fordham and Lee Citation2018, 269; on the right). For him, imprisonment has become a natural state. Hence, as he says goodbye to the Finch family and returns home, the full-page panel changes into the grid made up of smaller ones, and Boo’s freedom changes into his entrapment again.

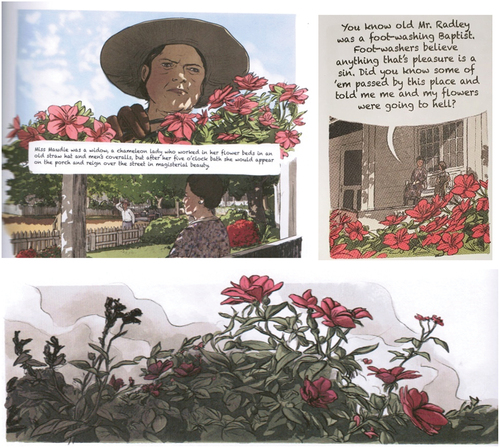

Miss Maudie is ostracised by Maycomb community because of her independence and her behaviour that is considered inappropriate for a real Southern lady. However, her isolation is marked differently, mostly through colour. In general, in the graphic novel a palette of subdued hues is used, with grey and beige dominating. It makes the images consistent and uniform while putting more emphasis on the rare elements coloured differently. The application of a vivid one, such as red or pink, implies that the people associated with them do not fit in with the general standards agreed upon in this community. Hence, Miss Maudie’s red flowers are the first visual cue of her lack of compliance with the local customs and her isolation from the rest of society (Fordham and Lee Citation2018, 53, 55; on the top). She is described as ‘a chameleon lady [wearing] an old straw hat and men’s coveralls’ (53). However, her unconventional outfit and behaviour are tolerated by the community only on the condition that she does not leave her house or her backyard dressed like that. It is an unwritten agreement, understood by everyone in town, although never expressed directly. As a result, she is imprisoned in her garden as long as she chooses to disregard the accepted social norms. Once she puts on a dress more suitable for a Southern lady in the afternoon, thus donning a mask, she inevitably gives up part of her freedom as she lets others dictate the rules. Her distinctness results in her ostracism from the community of respectable citizens, who express their disdain more or less openly, announcing that ‘[she and her] flowers are going to hell’ (Fordham and Lee Citation2018, 55; on the right). Defiant as Ms. Maudie seems to be, she still is a prisoner of societal constraints typical for that time and place.

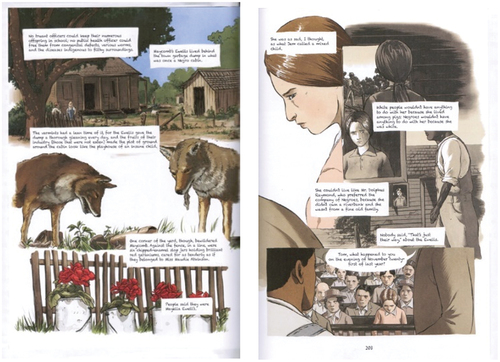

Contrasting colours are also used with reference to Mayella – a poor white girl abused by her father and rejected by the community. First, her predicament is implied by means of crimson red flowers in the corner of the Ewells’ yard, ‘cared for as tenderly as if they belonged to Miss Maudie Atkinson’ (Fordham and Lee Citation2018, 180; on the left). The flowers, just like the girl, draw everyone’s attention but do not receive proper care and therefore can flourish only for a short time. Moreover, being the only beautiful element in the otherwise old and dilapidated surroundings, the geraniums imply the girl’s imprisonment in the house and in the family with no perspectives, where grit and violence are the facts of life. Her distinction is further alluded to in the scene of the trial, where she is the only person wearing pink among a crowd dressed in dull beige and grey (Fordham and Lee Citation2018, 203; on the right). Again, it proves her isolation, still intensified by the fact that her attempt to break free from her prison, to feel loved for a while, means a death sentence for an innocent person. As the colour pink is a subdued, washed-out version of the colour red, the shift from the bright red flowers to the dull pink in court may imply her gradual compliance with societal norms – which, for a woman of her position, equals to being trapped in her previous life with no dreams and no perspectives. As she gradually blends into the background of the ‘white trash,’ she loses her distinctness and her individuality. Thus, she also loses any hope for a better life in which she could be special, or at least worthy of anyone’s attention.

The choice of a subdued colour palette only interspersed with more vivid elements can be a powerful tool, as it subconsciously attracts the reader’s attention to the fragments that are marked differently. It adds significance to the characters featuring the bright hues, and it captures the reader’s eye on par with the panel structure, the framing, or the symbolic use of fences. All these techniques are used efficiently to imply various characters’ alienation, as well as their entrapment in their racial, gender or class roles. Such visual cues are indirect and they work on a subconscious level. Nevertheless, their significance should not be ignored. Using such strategies, the graphic novel may give depth to the interpretation of the standard novel and it may focus the reader’s attention on the aspects previously underappreciated or even overlooked.

So, could the classic story defend itself 60 years after the original publication or should it be banned and forgotten? Fordham’s adaptation focuses on the significant social issues and it highlights the deep divisions along the lines of race, gender and class, but it does so in a new way, namely by incorporating them into the overall motif of entrapment and isolation. The community feels like a prison for the people who cannot or do not want to comply (Scout, Boo, Miss Maudie, and Mayella), as it limits their freedom and ostracises them, or even eliminates them to restore what the community understands as law and proper order (as shown in Tom’s case).

That kind of conduct inevitably rings a bell for the modern reader and helps them draw a parallel between the open and obvious injustice typical for the Jim Crow South and the present times, where racism is officially illegal and should be persecuted, but in reality it still is a fact of life in many places around the world, including the United States. Adapting a controversial work on race and gender set in the 1930s in the form of a comic, presumably more appealing for young audiences than traditional texts, naturally provokes questions about race, gender and class equality again. It may even seem to be a voice in the discussion of such issues in 2018, in the wake of Black Lives Matter movement and the deaths on many young black people in the streets at the hand of the police, typically biased against them. To Kill a Mockingbird shows clearly and directly where hatred based on prejudice and inequality may lead, and the graphic adaptation drives this point even stronger. By emphasising different themes and by introducing little but significant changes in the text that help the reader look at it with fresh eyes, Fordham’s adaptation sheds a new light on the well-known story. It concentrates on ‘the others’ marginalised by the community, and it puts them in the foreground when telling their stories. This way the graphic novel restores voice to the characters that were muted before, and brings back their dignity. It is an important change that enriches the experience of the classic story and transports it to the 21st century, to be appreciated by a new generation of readers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- American Library Association. 2013. Top 100 Banned/Challenged Books: 2000-2009. Accessed 25 May 2023. https://www.ala.org/ala/issuesadvocacy/banned/frequentlychallenged/challengedbydecade/2000_2009/index.cfm

- Baetens, J., and H. Frey. 2015. The Graphic Novel: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139177849.

- Cutchins, D., K. Meeks, and V. Eckart. 2018. “Adaptation, Fidelity and Reception.” In The Routledge Companion to Adaptation, edited by D. Cutchins, K. Krebs, and E. Voigts. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315690254.

- Elliott, K. 2014. “Rethinking Formal-Cultural and Textual-Contextual Divides in Adaptation Studies.” Literature/Film Quarterly 42 (4): 576–593.

- Fordham, F., and H. Lee. 2018. To Kill a Mockingbird. A Graphic Novel. New York City: Harper Collins Publishers.

- Hatfield, C. 2009. Alternative Comics: An Emerging Literature. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

- Hutcheon, L. 2006. A Theory of Adaptation. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203957721.

- Jenkins, H. 2020. Comics and Stuff. New York University Press. https://doi.org/10.18574/nyu/9781479831258.001.0001.

- Lee, H. [1960] 2020. To Kill a Mockingbird. London: Arrow Books.

- Meyer, L. R. 2013. “I Would Kill for You. Love, Law and Sacrifice in To Kill a Mockingbird.” In Reimagining to Kill a Mockingbird. Family, Community, and the Possibility of Equal Justice Under Law, edited by A. Sarat and M. M. Umphrey, 37–64. Amherst, Boston: Massachusetts UP.

- The New York Times. 2021. “What’s the Best Book of the Past 125 Years? We Asked Readers to Decide.” The New York Times. December 29, 2021.

- Seligman, M. 2010. “Foreword.” In Harper Lee’s to Kill a Mockingbird New Essays, edited by M. Meyer, I–XIX. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press.

- Shaw-Thornburg, A. 2010. “On Reading To Kill a Mockingbird: Fifty Years Later.” In Harper Lee’s to Kill a Mockingbird New Essays, edited by M. Meyer, 114–129. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press.