ABSTRACT

This study combines qualitative and quantitative research to examine perceptions held by rural households in Northern Ghana regarding the value of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) in the management of ecosystem services. Key informant interviews (n = 14), household questionnaire surveys (n = 195), field observations, and dissemination meetings were employed to collect data. Results suggest the regular use of different but interrelated forms of TEK, i.e. taboos and totems, customs and rituals, rules and regulations, and traditional protected areas, to manage ecosystem services through existing sociocultural mechanisms. However, household awareness of TEK did not equate with compliance. A wide discrepancy in views on TEK was observed across surveyed households. A generalized linear model (GLM) regression analysis suggests age to be the most significant determinant of TEK awareness and compliance. Compared with mature and younger adults, the elderly appear more likely to be aware of and comply with characterized TEK systems. Notwithstanding these findings, the use of traditional protected areas as a form of TEK appears to be highly valued by the majority of survey participants. Demand-led research aimed at examining TEK’s role in the face of changing socioeconomic and environmental conditions can contribute to the formulation and implementation of policy-relevant strategies.

EDITED BY Leni Camacho

1. Introduction

Against the backdrop of unprecedented global degradation and reduction in biodiversity and ecosystem services with impacts on human well-being over the last 50 years, there is a growing interest in the role of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) practices and systems of local communities in ensuring the sustainable utilization and management of ecosystems services. On a multilateral level, Article 8 (j) of the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity explicitly states the need to respect, preserve, and maintain knowledge practices of local and indigenous communities related to biological diversity (United Nations Citation1992). The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), since its establishment in 1988, has highlighted the role that TEK can play in addressing the negative effects of global climate change and variability. The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA) report, published in 2005, also identified TEK as relevant in addressing the current unsustainable utilization of different categories of ecosystem services (MA Citation2005). More recently, the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) has created opportunities for the inclusion of indigenous and local communities and their TEK systems in ecosystem and biodiversity assessment by making it a key component in its established conceptual framework (Diaz et al. Citation2015). On a local scale, several studies over the years have provided empirical evidence of past and present successes and challenges encountered in the application of local TEK in managing and governing natural resources in traditional and complex socio-ecological landscapes, as well as in dealing with changing conditions in different ecosystems (Usher Citation2000; Agrawal Citation2001; Elias et al. Citation2005; Liu Citation2006; Nyong et al. Citation2007; Ranganathan et al. Citation2008; Gómez-Baggethun et al. Citation2010; Takeuchi Citation2010; Molnar Citation2012; Parrotta & Trosper Citation2012).

Often regarded as a variant of indigenous knowledge, TEK broadly refers to any form of knowledge unique or peculiar to a particular society or culture that relates to their immediate environment. In addition to the term TEK that is adopted in this study, other terms commonly used in the literature include indigenous local knowledge (ILK), traditional knowledge (TK), traditional forest knowledge (TFK), local ecological knowledge (LEK), and indigenous ecological knowledge (IEK). Despite these variations in terminology, the general consensus remains that such knowledge systems have evolved over many years and are retained by local communities outside the formal or Western scientific domains. In the context of this research, Berkes’ definition of TEK as ‘a cumulative body of knowledge and beliefs handed down through generations by cultural transmission, about the relationship of living beings (including humans) with one another and with their environment’ (Berkes Citation1993, p. 3) is more encompassing and applicable to local-scale considerations. A deeper analysis of Berkes’ definition reveals that TEK systems are constantly evolving, contrary to some widely held assumptions that TEK is static and archaic, a view that has been rightly refuted by many empirical studies (Agrawal Citation1995; Berkes et al. Citation2000; Allison & Badjeck Citation2004; Eyssartier et al. Citation2011; Gómez-Baggethun & Reyes-García Citation2013).

Current renewed interest in the role of TEK therefore marks a welcome shift from Western approaches to ecosystem services management and governance, which in most cases regard local communities and their knowledge systems as detrimental to the functioning of ecosystems (Fairhead & Leach Citation1998; DeGeorges & Reilly Citation2008). Consequently, many have argued that the extensive utilization of Western knowledge systems in the management of ecosystem services is responsible for relegating TEK to the background and is thus a major reason for the current decline of TEK across socioecological regions (Kingsbury Citation2001; Turner & Turner Citation2008; Berkes Citation2012).

In many rural areas of Ghana, vast amounts of TEK are known to exist and to be applied through well-established social and cultural mechanisms in the form of local beliefs, values, rituals, customs, and taboos for managing natural resources (Dorm-Adzorbu et al. Citation1991; Ntiamoa-Baidu Citation1995; Abayie-Boateng Citation1998; Appiah-Opoku & Hyma Citation1999). A number of studies have reported a general and increasing decline in the local communities’ application of these valuable knowledge systems and practices in managing local ecosystems (Millar Citation2003; Hens Citation2006; Gyampoh et al. Citation2008). Communities in recent decades have had to contend with the many challenges associated with rapidly changing socioeconomic conditions. These challenges are further aggravated by the effects of climate change and variability, with prolonged drought and flooding being experienced (Gyasi Citation2002; van De Geest Citation2004; Acheampong et al. Citation2014). Such rapidly changing socioeconomic and environmental conditions may compel communities and households to abandon or disregard local TEKs that have long been applied in regulating and controlling ecosystem services for livelihood sustenance. In the face of these changes, it has become necessary to examine how rural communities’ TEK knowledge systems relating to ecosystem services management are currently perceived and applied in the face of increasing threat to biodiversity and ecosystem services across scale (TEEB Citation2010).

The objective of this study is to enhance understanding of TEK’s role in the management and governance of ecosystem services by conducting qualitative and quantitative assessments of households’ perception regarding the use and relevance of community TEK practices and systems. Toward this end, the study formulated and analyzed responses to four principal questions:

What are the existing forms of TEK for managing ecosystem services across the four study sites?

To what extent is awareness and compliance of existing TEK different across communities?

Which socio-demographic variables have the most influence on awareness and compliance with TEK? and

How do views on the role of TEK in ecosystem management vary across different age groups?

Section 2 of this paper provides some relevant geographical and socioeconomic information on the study area, the techniques employed in collecting and analyzing data, as well as some study limitations. Section 3 focuses on the study results, which are categorized in accordance with the principal research questions identified above. Section 4 is devoted to the discussion of the research outcomes, while Section 5 examines the practical and theoretical policy implications of this study. The concluding Section 6 provides insights into the role of TEK in managing ecosystem services by summarizing key findings and examining the way forward.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study area

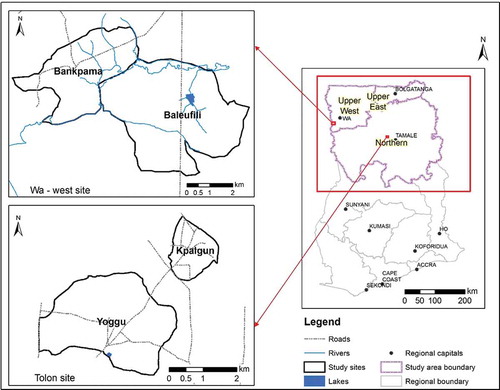

Northern Ghana comprises three administratively autonomous regions, namely the Northern, Upper West, and Upper East, which together cover a land area of approximately 97,702 km2 (41%) of Ghana’s total land mass (). Their characterization is largely defined by their peculiar semi-arid climatic and physical conditions, high poverty levels ranging from 68% to 88% across regions attributed to many years of social, political, and economic exclusion (Whitehead Citation2006; Songsore Citation2011; World Bank Citation2011), and extreme vulnerability to climate change compared with the other parts of Ghana (Dietz et al. Citation2004; Acheampong et al. Citation2014). The majority of the population here is rural (Northern: 69.7%, Upper West: 79.5%, and Upper East: 76.4%) meaning that there is high reliance on the local ecosystem to meet livelihood needs (Boafo et al. Citation2014). Rain-fed agriculture, which is a blend of crop farming and livestock raising, is undertaken by the majority of the population in this area (approximately 78%) (Ghana Statistical Service Citation2013). Crop-farming systems are dominantly traditional and can involve the use of hoes, organic fertilizer, and burning, although gradual modification is being witnessed across the region.

In this semi-arid ecosystem, the mean annual temperature is approximately 28°C, with daily temperatures ranging from evening lows of approximately 15°C to daytime highs of 40°C. Average annual rainfall is between 800 and 1100 mm. Relative humidity varies widely, averaging approximately 54% (Ghana Meteorological Agency Citation2015). Vegetation is dominated by herbaceous grasses, shrubs, and drought-resistant trees such as Vitellaria paradoxa, Parkia biglobosa, and Ceiba pentandra. Owing to the sparse ground cover most months of the year, evapotranspiration is very high. Drought and seasonal food shortages are common. In response, seasonal migration of youthful population especially females to urban centers in southern Ghana to work as porters is widely undertaken (Awumbila & Ardayfio-Schandorf Citation2008).

For the purpose of this study, four rural communities were selected for the focus of an in-depth survey. These communities include Yoggu and Kpalgun located in the Tolon district of the Northern region and Baleufili and Bankpama in the Wa West district of the Upper West region (, ). Community in the context of this study refers to a group of local people living and interacting with one another. These four communities were selected because they have (1) common livelihood activities and share common boundaries; (2) high reliance on the local ecosystem for meeting both primary and secondary livelihood needs; and (3) different levels of proneness to perennial drought and flooding events. Yoggu and Kpalgun lie on a relative flat and level landscape. Compared to Baluefili and Bankpama communities, Yoggu and Kpalgun are considered to be drought prone (Antwi et al. Citation2014). Baleufili and Bankpama, on the other hand, are located on a fairly uneven elevation and undulating landscape. Both communities are impacted significantly by the Black Volta River, which, along with its tributaries, drains through the area and leaves communities’ resources, especially farmlands, flooded during the short rainy season (Boafo et al. Citation2014).

Table 1. Geographic location, land area, and estimated population of study sites.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Field data collection processes and techniques

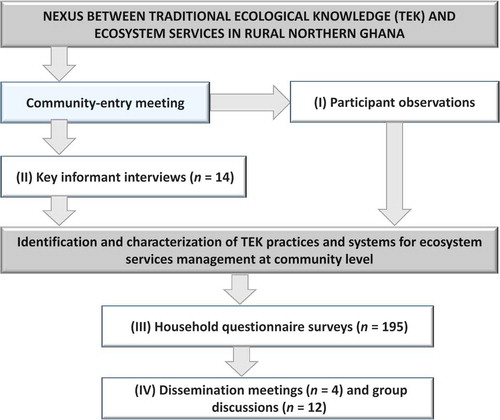

Survey data were collected between February 2013 and September 2014. A mixed-method approach using quantitative and qualitative techniques was employed in this study to collect data (Creswell Citation2014). Structured field data collection activities began with community-entry meetings with the community head and other elders as well as with opinion leaders. Such meetings were used as a medium for the study team to explain the research objectives and the expected role of the community and its members. During such meetings, oral consent was sought from community leaders, paving the way for the team to undertake the main field activities: participant observations, key informant interviews, household questionnaire surveys, and dissemination workshops and discussions ().

2.2.1.1. Participant observations

Participant observation activities entailed visits to elemental locations such as water points, sacred groves, shrines, community woodlots, and fallow lands where TEK is perceived to be applied or observed. Social events and ceremonies, such as marriages, funerals, and child naming ceremonies, as well as daily and seasonal livelihood activities, including preparation, planting and harvesting crops, food processing, and collection of wild food and plants, were relevant avenues for identifying and assessing TEK forms applied at both community and household levels. Data were collected in the form of field notes and photographs.

2.2.1.2. Informant interviews

To gain a deeper understanding and appreciation of TEK as it relates to different categories of ecosystem services, key informants were selected under the guidance of the community head (Tongco Citation2007). A snowball sampling technique was used to identify more informants (Bernard Citation2005). Targeted informants were interviewed using a semi-structured interview guide between February and March 2013. Overall, 14 informants across the study communities: Yoggu (n = 5), Kpalgun (n = 3), Baleufili (n = 4), and Bankpama (n = 2) were interviewed. Informants comprised household heads, herbalists, rainmakers, lead farmers, and assemblymen (formal government representative at the community level). To aid informants in the identification of TEK practices related to ecosystem services, the study team relied on data from Boafo et al. (Citation2014), whose study in the same study sites inventoried and assessed households’ utilization and management of critical provisioning ecosystem services (Appendix 1). Several studies (Sinclair & Walker Citation1999; Millar Citation2003; Tengo et al. Citation2007; Ormsby & Bhagwat Citation2010) have investigated the existence and application of TEK in managing natural resources in different socio-ecological regions adopting similar approaches. Discussions with interviewees centered on (1) the identification of different forms of TEKs that relate to the control, regulation, and overall management of ecosystem services; (2) the spatial and temporal characteristics of existing TEK practices; and (3) the views on the usefulness and challenges associated with TEK application. Interviews lasted on average between one and two hours. In some instances, interviews were interrupted if the informant became exhausted or had to attend to an urgent task. Most of the interviews were recorded and later transcribed.

2.2.1.3. Household questionnaire survey

The qualitative information gathered from the earlier field activities (entry meetings, field observations, informant interviews) was used to develop a household questionnaire instrument. This questionnaire was used to investigate respondents’ knowledge and general perceptions of existing TEK in managing the local ecosystem. The questionnaire was also used to collect information on respondents’ sociodemographic and economic characteristics. Face-to-face interviews using the questionnaire were carried out between August and September 2014. Based on the proven assumption that holders and users of TEK knowledge vary across and within households (Gómez-Baggethun et al. Citation2010), the selection of respondents for this survey was carried out in different stages. First, 65 households representing a sample size of about 10% of the total households in each of the four study communities were randomly selected [Yoggu (n = 22), Kpalgun (n = 16), Baleufili (n = 14), and Bankpama (n = 13)]. Second, applying a quota sampling technique, three individual respondents in each sampled household were purposively identified and interviewed using their age differences as the benchmark. These three respondents were categorized as follows: (1) younger adults (respondents aged between 18 and 40 years); (2) mature adults (respondents aged between 41 and 60 years); and (3) the elderly (respondents aged 61 years and above). Furthermore, the above age categorizations were undertaken with the assumption that individual respondents in each category had varying levels of interaction with their biophysical environment on the basis of them being either active or non-active out-migrants. Adopting representative sampling was necessary as it has been shown that knowledge varies across individuals and groups (Reyes-Garcia et al. Citation2005). Overall, 195 face-to-face interviews were conducted across the four study communities: Yoggu (n = 66), Kpalgun (n = 48), Baleufili (n = 42), and Bankpama (n = 39). The majority of the face-to-face interviews were prearranged; this contributed significantly to achieving a 100% response rate.

2.2.1.4. Dissemination meetings

To identify further knowledge and validate the already-collected information on TEK, four findings dissemination and feedback meetings with community members were organized (one per village) in September 2014. The meetings took place at the communal meeting point in each study community. The meetings were organized in collaboration with the community heads after the research team had informed him of the goal and agenda. Meetings usually lasted one and a half hours. Immediately after each dissemination meeting, small group discussions stratified into elderly and mature adults and younger adults were held separately. Discussions often lasted between 30 and 35 minutes, with an average participation of 11 individuals. The discussions aided in clarifying contentious issues that emerged during the dissemination meetings.

2.2.2. Data analysis

Qualitative data were analyzed by categorizing the information obtained, which mainly came from reflexive and field notes taken during field survey activities (Strauss & Corbin Citation1998). Quantitative data were categorized, numerically coded, and analyzed using the IBM Statistical Product and Service Solutions package (SPSS version 20). Pearson Chi-square (Χ2) tests of independence were used to determine the significance of associations between categorical (dichotomous and nominal) variable pairs. To analyze the influence of socio-demographic variables on respondents’ awareness of and compliance with identified TEK, a simple generalized linear model (GLM) using the R 3.1.2 software was applied. The explanatory variables of the model were age group, gender, educational status, length of stay, residency status, and religion. The error distribution was assumed to be binomial, and the logit link function was chosen. The effects of explanatory variables were evaluated by checking whether the Wald 95% confidence interval for each coefficient included zero.

2.2.3. Study limitations

In this study, two major limitations that might have influenced the general findings need to be emphasized. First, four local dialects namely Dagbani, Dagaare, Hausa, and Waala were used as the primary mechanism for collecting field data and then simultaneously translated into English. Under such circumstances, it is possible that some relevant information might have been lost or mistranslated. Second, answers given by respondents regarding their awareness and compliance with TEK systems may be influenced by variables not included in this study.

3. Results

3.1. Identification and characterization of TEK

From community entry meetings, field observations, and key informant interviews, different and interdependently used TEK practices for managing different categories of ecosystem services were identified across the study communities (). Informants elaborated that TEK is applied at household and community levels through sociocultural mechanisms and is enforced by local traditional authorities and institutions. Results from the study indicate high-level similarities in the use and application of TEK practices across all four study communities. According to the survey, TEK is manifested in daily, seasonal, periodic, and temporal livelihood activities and systems such as farming and collection of wild food or plants to the performance of rituals and ceremonies.

Table 2. TEK characterization, category of ecosystem service(s) targeted, and applicability in studied communities.

In Kpalgun and Yoggu villages, a folk tale holds that when the original settlers (ancestors) were migrating, a crocodile guided them to cross a big river. Thus, the West African crocodile (crocodylus suchus) is regarded as a totemic (a revered animal) and must not be killed for food and other purposes. Informants across all study communities emphasized that because the identity of their entire community is dependent on the provisions made to them by the local ecosystem, they deem it obligatory to use the TEK passed on to them by their ancestors to sustainably manage it for future generations.

Based on spatio-temporal considerations with emphasis on their peculiar functions and characteristics, identified TEK practices were characterized into four main systems: (1) TEK in the form of taboos and totems, (2) TEK in the form of customs and rituals, (3) TEK in the form of rules and regulations, and (4) TEK in the form of traditional protected areas. The above characterization was useful in obtaining household views and perceptions of different forms of TEK in the communities. Thus, it is important not to regard them as entirely independent as they all contribute to performing a common conservation and ecosystem management function. These different aspects with specific examples are shown in and are also described in detail in the subsequent sections.

3.1.1. TEK in the form of taboos and totems

This category of TEK enjoins community members to partly or completely refrain from collecting and/or using part or whole of certain plant and animal species. In the study, community taboos are considered necessary management strategies for reducing over-harvesting of critical provisioning services as well as restoring endangered animal and plant species. As hunter informants regularly elaborated, most taboos forbid the killing of different types of animals under certain circumstances, such as when they are pregnant, nursing young ones, or mating. Taboos also allow or forbid the collection or use of certain wild plants for specified purposes only. For example, the shea tree (vitellaria paradoxa) has many taboos relating to the use of different parts at different times and locations (). When taboos are applied to certain animal species as in the case of the crocodile and African rock python (python sabae) in the study communities, such a species is referred to as a totem (Awedora Citation2002). Taboos may be imposed on a daily, weekly, or seasonal basis and may apply to different individuals on the basis of age, gender, or status. In the study communities, violating local taboos will require the sacrifice of fowls or in some cases a zebu (humped cattle) to appease the gods. Informants provided the following responses as examples to illustrate what could happen to any individual who violates taboos: ‘The person, if a woman, could become barren’; and ‘You will be bitten by an invisible snake’.

3.1.2. TEK in the form of customs and rituals

Customs and rituals are specific social behaviors, practices, and ceremonies performed on a regular basis by individuals or specialized people within the study communities. This category of TEK is performed either proactively or reactively and is considered a duty to be fulfilled to enhance access to critical ecosystem services or promote the land’s productivity. Examples in the study communities include consulting traditional healers to perform rites and pacifying the gods with drinks for rains during a drought or for a good harvest, or celebrating a new harvesting season for staples by sharing with neighbors. In Kpalgun and Yoggu communities, a ceremony for yam harvesting is regularly performed usually at the household level. Furthermore, it is a custom that parts of the shea tree can only be harvested for firewood when a newborn is introduced to the community.

3.1.3. TEK in the form of rules and regulations

Rules and regulations governing TEK facilitate common agreement on the use or non-use of a particular ecosystem service. At critical stages when a particular ecosystem service is found to be at the point of extinction or vulnerable to environmental changes, communities – through their traditional authorities – may enact new rules to regulate the service’s withdrawal to ensure total or partial protection. Strict sanctions and fines are levied on individuals or households found to have violated such rules and regulations; these rules and regulations usually complement other aspects of TEK and hence cannot function independently. In all four study communities, for example, it is a common rule that one can harvest the fruit of the shea tree from community-owned land, but if at the tree is located on an individual’s farm, permission needs to be sought from the farm owner before harvesting. Failure to comply with such rules and regulations often results in a fine of money or livestock, public flogging, and, in extreme cases, expulsion from the village.

3.1.4. TEK in the form of traditional protected areas

This category of TEK provides the basis for communities to protect and conserve specific locations of their local landscape. Within the study communities, these locations include sacred groves, woodlots, riverbanks, rice valleys, and fallow land (Millar Citation2004). These areas are protected by virtue of their unique and peculiar contribution to the social, economic, cultural, and environmental well-being of communities and households. For example, according to inhabitants, sacred groves harbor their ancestors and gods of the land who have sustained them for generations (Tengo et al. Citation2007). These groves are also regarded as a place to find rare plants and animals used for medicinal and ritual purposes. Boakye-Danquah et al. (Citation2014) found high soil organic carbon content (a proxy indicator of a healthy ecosystem) in the sacred groves of Tolon when compared to land used for other types of activities. The strict protection accorded to groves accounts for this difference. In Yoggu and Kpalgun communities, entrance to traditional protected areas was found to be highly restricted. The research team was allowed to enter the sacred groves only under the guidance of a village elder after a thorough consultation with the chief. In addition to the smaller groves scattered within the Yoggu and Kpalgun villages, the Jaagbo grove was frequently mentioned by participants in field survey activities as one of the biggest and most highly revered by households within and across the area (Corbin Citation2008).

3.2. Assessment of community- and household-level TEK awareness and compliance

3.2.1. Intercommunity comparison of TEK awareness and compliance

The results of the household questionnaire survey suggest that a respondent’s awareness of a TEK did not necessarily equate with compliance. Results indicate a high degree of variation between awareness and compliance, as reflected in the higher responses for awareness of all four TEK systems compared to compliance (). The response rate for all four TEK indicates traditional protected areas received the highest response rate in terms of both awareness (84%) and compliance (69%). Taboos and totems ranked second (76% and 54%, respectively), followed closely by customs and rituals (70% and 45%, respectively), with rules and regulations being the least (67% and 44%, respectively).

A comparison of awareness and compliance among the study communities revealed that across the four characterized TEK systems, households in Bankpama community exhibited significantly different levels of awareness and compliance compared to the Yoggu, Kpalgun, and Baluefili communities. For instance, whereas traditional protected areas were the least rated by households in Bankpama in terms of compliance and awareness, households in Yoggu, Kpalgun, and Baluefili rated this aspect the highest across the four aspects (). An informant in Bankpama may have provided one plausible explanation for the observed variation during an interview:

‘Because we are not natives of this area, we always have to seek permission from the chief of Baleufili to use any area of land that is outside our original boundary. Moreover, our population has increased, thus putting pressure on the land for farming. Even now we cannot allow the land to lie fallow as we used to do some years back’.

3.2.2. Influence of socio-demographic characteristics on TEK awareness and compliance

To examine the influence of household socio-demographic characteristics on TEK awareness and compliance, a simple GLM regression analysis was performed. Results showed significant intergenerational (age groups) differences in awareness of customs and rituals, with the elderly group much more likely to be aware compared with mature adults (p ˂ 0.1) and younger adults (p ˂ 0.001). Regarding compliance, mature adults compared with the elderly (p ˂ 0.5) appeared less likely to comply with taboos and totems. The results also indicated a statistically significant difference between younger adults and mature adults with respect to compliance with taboos and totems (p ˂ 0.001); rules and regulations (p ˂ 0.5); and traditional protected areas (p ˂ 0.1) ().

Table 3. Influence of socio-demographic characteristics on TEK awareness and compliance (generalized linear model regression analysis).

The analysis showed that, compared with women, men were more likely to be aware of rules and regulations (p ˂ 0.1). Anecdotal evidence from informants in the study communities indicates that men dominate in leadership positions, and are also responsible for most decision-making. Length of stay in a village has a statistically significant effect on awareness of traditional protected areas. Results showed that respondents who have lived in their community for more than 50 years were more likely to be aware of the existence of protected areas than those who have been residents for less than 10 years (p ˂ 0.1).

The GLM regression result also revealed the influence of residency status (settler or native) on awareness of taboos and customs, as migrants were found to be less likely to be aware of taboos and customs (p ˂ 0.1) than the natives. Again, when compared to natives, migrants were less likely to be aware of traditional protected areas (p ˂ 0.001). This distinction also applies to compliance with customs and rituals; the results indicate that natives were more likely to comply compared with migrant respondents (p ˂ 0.5). Religion appeared to have a significant effect on the awareness of customs and rituals as well as of rules and regulations. Compared with Muslims, traditionalists were more likely to be aware of customs and rituals (p ˂ 0.1). By contrast, Muslims were found to have a higher level of awareness of rules and regulations than Christians (p ˂ 0.1).

3.3. Intergenerational perceptions of TEK for ecosystem management

3.3.1. Respondents’ views on the current role of TEK in ecosystem management

Respondents were asked to share their views on the changing role of TEK for ecosystem management by choosing one of three options (agree, disagree, and don’t know) in response to three different statements. The three statements were: (1) TEK remains relevant for ecosystem services management; (2) TEK should be disregarded, as it is no longer applicable for ecosystem services management; and (3) government agencies should support communities to protect and preserve their good TEK systems. presents the results on the views of respondents stratified across the three age groups. For the first statement, TEK remains relevant for ecosystem services management and governance, a significant statistical variation in opinion between age groups was observed. An overwhelming proportion of the elderly (83.1%, p ˂ 0.01) agreed with this statement, followed by 69.2% of mature adults. Only 18.5% of the younger adults agreed. By contrast, 58.5% of the younger adults disagreed with this statement (p ˂ 0.01), compared with 18.5% of mature adults and only 10.8% of the elderly. Younger adults also gave the highest percentage of ‘don’t know’ answers (23.0%, p ˂ 0.05), followed by 12.3% of mature adults and 6.2% of the elderly. The above discrepancy in opinion may be supported by the words of a 73-year-old informant farmer at Kpalgun community when he stated:

The main reason for the continuous survival of all the tanga (vitellaria paradoxa) and dawadawa (parkia biglobosa) trees you see in this community is that we used the TEK practices passed on from our ancestors to preserve them. If we had cut them indiscriminately as some people (especially the youth) are doing nowadays, I am sure we all would not have survived till now, so I am confident that TEK will still be relevant.

Table 4. Inter-generational (age-group) views on the role of TEK in ecosystem services management.

There was also a significant variation in respondents’ views regarding the second statement: TEK should be disregarded, as it is no longer applicable for ecosystem services management (). While the majority of the younger adults (66.2%, p ˂ 0.01) agreed with this statement, the strongest level of disagreement came from the elderly (81.5%, p ˂ 0.01), followed by 30.8% of mature adults and 16.9% of younger adults disagreeing. Interestingly, the ‘don’t know’ responses were dominated by mature adults (43.1%, p ˂ 0.01), followed by younger adults (16.9%) and the elderly (7.7%). These results strongly validate the views of respondents for the first statement. A 28-year-old younger adult at Baleufili community supported his view by saying:

Why should one stay here to apply all the numerous TEK practices when they do not even work anymore? Even my father who has been farming for so many years in this village tells me that he has started using modern practices. Personally, I do not think TEK is practical; I prefer to travel to Kumasi to work for money.

Regarding the statement ‘Government agencies must support communities to protect and preserve their good TEK systems’, respondents’ views were fairly and evenly spread across each of the three response options. However, younger adults (60%) compared with mature adults (53.8%) and the elderly (46.2%) agreed, while the majority who disagreed with the statement were the elderly (38.5%, p ˂ 0.05). The elderly often cited their distrust of government institutions and agencies based on their past experiences, and hence felt that they could not rely on the government for any form of support.

3.3.2. Prioritizing TEK for use and application

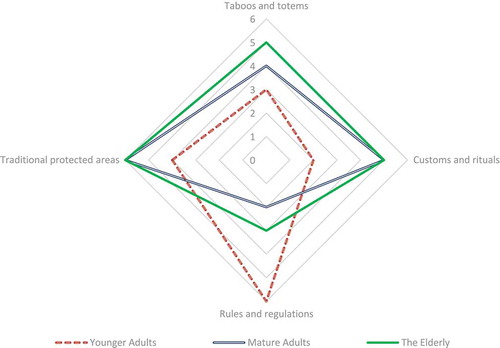

Using a six-point Likert scale (1 = not a priority, 2 = low priority, 3 = somewhat of a priority, 4 = moderate priority, 5 = high priority, and 6 = essential priority) in the questionnaire surveys, respondents were asked to prioritize their choice of preference of the four identified TEKs given the opportunity (). Carter et al. (Citation2000) applied a similar point-scoring system to evaluate attitudes toward the conservation of non-game birds and their habitats in the United States.

Overall, the analysis indicates a wide contrast in the preferred choice of TEK for managing the local ecosystem. Among the younger adults, rules and regulations were given an essential priority rating, the highest in terms of preference for application. Traditional protected areas and taboos and totems were both given a moderate priority rating, with customs and rituals being given somewhat of a priority rating, indicative of it being less preferred as a TEK management practice for ecosystem services. As one respondent at Kpalgun village during the survey made clear:

My grandfather strongly believes in all the taboos, totems, and rituals in this village for regulating the harvesting of dawadawa (parkia biglobosa). He taught me about the importance of tibuni (sacred groves and shrines) because his father transferred the knowledge to him. Now, I feel it is not an effective practice so I do not adhere to it, I prefer rules and regulations which is free from spiritualism. Moreover, I am a Christian and it is not allowed.

Results from mature adults indicate that traditional protected areas are this group’s most preferred TEK, and hence its essential priority rating. Customs and rituals were given a high-priority rating, whereas taboos and totems were offered a moderate priority. Rules and regulations as a TEK system were given a low-priority rating. A mature adult respondent during the face-to-face interview at Yoggu community explained:

The reason why I believe in the use of traditional protected areas and taboos and customs more than rules and regulations is that they have been used by our ancestors to preserve this very land for us. These practices scare people, unlike rules and regulations which are more recent and have not really been observed, especially by the younger generation.

Similar to the results from mature adults, the elderly also gave traditional protected areas an essential priority rating. Taboos and totems and customs and rituals were assessed as a high-priority TEK, with rules and regulations being given the lowest priority score. The analysis here corroborates the views of different age groups regarding the role of TEK for managing the local ecosystem as was found earlier.

4. Discussion

Results from the survey suggest that households in all four study communities interdependently use and apply different forms of TEK aimed directly and indirectly at regulating or controlling different categories of ecosystem services that are embedded in local sociocultural mechanisms (Berkes et al. Citation2000; Colding & Folke Citation2001). Despite the significant geographical distance between communities in Tolon (Yoggu and Kpalgun) and those in Wa West (Baleufili and Bankpama) districts, high similarities in TEK practices across all four study communities were noted (). These similarities may be attributed to the limited environmental differences (vegetative and climatic) and common socioeconomic and cultural conditions across Northern Ghana. A more obvious explanation can be that communities recognize TEK as the most practical and readily available tool for dealing with the common challenge of sustainably managing limited and diminishing natural resources against the backdrop of environmental and socioeconomic changes. Observable differences in practices can be attributed to local-scale variations in ecosystem conditions.

With households known to be highly dependent on provisioning services (Boafo et al. Citation2014), it was not surprising that most informants interviewed considered TEK an economic and social asset, as it contributes to ensuring the productivity and sustainability of the local ecosystem. Key informants and respondents from face-to-face interviews across the study communities cited a number of examples to elaborate on how their local environment has been maintained largely due to the active and effective application of TEK passed on to them from preceding generations. A classic example of TEK benefits that emerged throughout the field survey was that in the long dry seasons, when vegetative cover is almost non-existent on the land, unprotected and bare soils around settlements are enriched by evenly spreading droppings from livestock (mainly cattle). The dung, along with other decomposed organic materials from daily household activities, serves as the main nutrient enhancement strategy for compound farms.Footnote1 This particular traditional technique of land management could be the reason crops such as maize, peppers, and groundnuts flourish annually on compound farms despite intensive land use (Derbile Citation2009). Findings from Boakye-Danquah et al. (Citation2014) study in Fihini at the Tolon area on farm land management showed that, apart from sacred groves, compound farms retained the highest soil organic carbon content, largely because of the use of intensive management practices involving household organic materials, further supporting this relationship.

The high discrepancy between locals’ awareness and compliance with the four characterized TEK systems – taboos and totems, customs and rituals, rules and regulations, and traditional protected areas as observed in this case study – calls into question the usefulness of TEK for rural communities. With awareness not equating to compliance, as evidence in the comparatively low and declining level of compliance with all TEK aspects (), it is possible that enforcement of TEK is weak overall, owing to closely related social, economic, cultural, and environmental factors such as migration, education, land tenure arrangements, climate variability, and change, and effects of drought and floods are known to significantly impact livelihood systems in Northern Ghana (Dietz et al. Citation2004; Acheampong et al. Citation2014). Similarly, Gibson et al. (Citation2005) discussed effective enforcement as a required condition if natural-resource management is to be successful. Even with the common patterns in household awareness and compliance of TEK systems in the study communities, with traditional protected areas scoring the highest rating in terms on both awareness and compliance, it is worth noting that the views of households in Bankpama community deviated significantly from this observed trend (). This is attributed to the fact that, compared with the other three communities, Bankpama is dominated by an immigrant population, meaning that they possess less-accurate detailed adaptive knowledge of their local ecosystem compared to natives who have resided there for a longer period (Atran Citation2001).

Overall, the survey results suggest the weak influence of socio-demographic variables on awareness and compliance of all TEK systems. However, the statistically significant relationships between local inhabitants’ awareness of and compliance with different aspects of TEK as observed in this study underscore the variations in their use and application across the study sites and regions (). Findings from this study corroborate with those of previous research conducted in other parts of Ghana (Anane Citation1997; Sarfo-Mensah & Oduro Citation2010) and the world (Ulluwishewa et al. Citation2008). The significant effect of age on awareness of customs and rituals and traditional protected areas can be directly attributed to rapidly changing socioeconomic and environmental changes across the study area (Millar Citation2004; Songsore Citation2011). The interplay between the perennial out-migration by youthful populations to Southern Ghana and the general disinterest in agriculture are plausible explanations for the observed variations in TEK awareness and compliance across age groups. Since the majority of the youthful population in the study communities move to urban centers in search of jobs, old people remain and, therefore, have a high awareness and compliance compared with the younger and matured adults. As observed during household interviews, the majority of interviewees were returning migrants who had plans of going back after a short stay. It is therefore not surprising that, compared with younger and mature adults, the elderly were more likely to be aware of and comply with the observed TEK. However, the lack of a receptive population to transmit and operationalize TEK in the study communities, the erosion of once-resilient and effective practices for the identification, utilization, and management of ecosystem services are imminent, as is happening in other parts of the world.

The result that men were more likely than women to be aware of rules and regulations provides evidence of the ingrained traditional system of leadership in the study communities, which often excludes women from public decision-making. The fact that women sampled for household questionnaire interviews were often hesitant to participate, even in the absence of men, is evidence of strongly gendered roles. Results indicate that respondents who have stayed longer in the community (more than 50 years compared to less than 10 years) are more likely to be aware of the existence of traditional protected areas; it is therefore unsurprising that, compared with migrants or settlers, natives were more likely to be aware of taboos and customs as well as traditional protected areas, and also more likely to comply with customs and rituals (). This influence of religion on TEK-based awareness of customs and rituals as well as rules and regulations can be attributed to the significant role played by traditional authorities in the enforcement of TEK. In comparison with Christians and Muslims, traditionalists are more likely to be the holders and enforcers of TEK knowledge, and hence their high awareness overall.

In the study, intergenerational views on TEK’s roles in ecosystem management were found to be highly contradictory. Whereas most mature adults and the elderly still perceived TEK as relevant for managing diverse ecosystem services, the younger adult generation overwhelmingly dismissed TEK (). An explanation for the high proportion of mature adults and the elderly holding positive views on TEK reflects these groups’ constant engagement with the local environment through livelihood activities such as farming, wild food collection, and others. Analysis of informant interview transcripts revealed that supporters of TEK view it as critical in supporting formal knowledge systems in managing the local ecosystem. Conversely, younger adults’ high propensity to migrate to urban centers means they lack practical knowledge of TEK practices and their usefulness as used in managing ecosystem services.

Even though the opinions held by different age groups did not vary greatly for the question of whether government should support the maintenance of good TEK systems, different reasons can be adduced for their views, relating strongly to the preferred form of TEK system for managing ecosystem services. As the household survey revealed (), younger people prefer the application of rules and regulations, which they view as more modern and also lacking spiritual or religions connotations, which are perceived to be associated with disrespecting taboos and totems, customs and rituals, and traditional protected areas. The mature adult and elderly groups, however, believe that the government cannot be trusted to manage ecosystem services and that, therefore, other TEK practices, such as taboos and totems, customs and rituals, and traditional protected areas should continue to be applied. This lack of trust in government by mature adults and the elderly may stem from past natural resource management policies and practices performed by formal governance systems, which have often undermined local peoples’ access to critical ecosystem services such as bush meat and fuel wood. Recognizing that modern governance systems cannot be ruled out completely in the management of ecosystem services, a substantial number of elderly participants (nearly half) did support a role for government institutions and agencies.

It is, however, important to note that the apparent lack of trust in government agencies expressed by a large proportion of mature adults and the elderly can be a stumbling block in efforts to build synergy between TEK and formal ecosystem services management strategies as people may not be willing to share TEK that may be relevant for the conservation and sustainable use of ecosystems.

5. Policy implications

As findings from this study have demonstrated, TEK is gradually being abandoned by communities and households in rural Northern Ghana as a result of the combination of rapid changes to socioeconomic, cultural, and environmental conditions. Considering the effects that this has on ecosystem services utilization and management across in rural landscapes policymakers in Ghana need to act urgently to design and implement proactive and practical measures as part of rural development policies. This is necessary because, despite the country’s high involvement in ratifying many international and multilateral policy initiatives targeted at reviving TEK, there appears to be little or no clear action at the national, regional, or local levels toward this end, resulting in little scientific knowledge on TEK.

This study recommends the development of a participatory methodology for assessing the TEK of local communities, identifying, collecting, measuring, validating, and monitoring its contents and use. For such an assessment to be successful, local communities need to collaborate closely with government agencies and departments, academia, and nongovernmental organizations, all of which need to play a major role at different stages. Local communities’ active involvement will go a long way toward overcoming their perception of their knowledge system being marginalized (often the case) or ‘stolen’ from them. In addition to having national relevance, the outcome data can serve as a vital tool for international and multilateral biodiversity and ecosystem assessment programs, such as the ongoing IPBES, which counts assessment of existing knowledge systems as one of its key functions (Diaz et al. Citation2015).

Furthermore, policymakers should mainstream TEK into formal educational curricula right from the primary level. This might help promote knowledge, understanding, and appreciation of TEK associated with the sustainable management of ecosystem services at an early age. In the context of Northern Ghana, where youthful populations migrate to the urban south even before completing their basic education, this could be an important step toward bridging the current wide gap in awareness between younger and elderly populations that this study found. It is recommended that informal education stakeholders such as parents and traditional authorities be actively engaged in the transmission of TEK knowledge in formal school systems. These stakeholders can contribute by offering practical sessions to students in their local context. Finally, the study recommends that policymakers enact ecosystem management policies and conservation strategies that pay attention to the links between local communities and nature.

6. Conclusions

While recognizing that modern scientific knowledge is invaluable in ecosystem services management, the need remains to incorporate resilient and practical forms of TEK held by local communities, as both empirical data and research outcomes have shown these to be of great significance especially in this era of global environmental change (Turner & Berkes Citation2006; Takeuchi Citation2010). This study explored community and household knowledge and perceptions of TEKs role in the management of ecosystem services through a case study of four rural communities in Northern Ghana.

Findings suggest that diverse forms of TEK developed over generations are still being applied by communities and households in the form of taboos and totems, customs and rituals, rules and regulations, and traditional protected areas. Results from the present study indicate the existence of an inverse relationship between awareness and compliance with TEK systems, which is reflected in the relatively high awareness and low compliance of all TEK categories assessed across the study communities. A high variation among age groups was found with regard to the respondents’ views on the role of TEK in sustainable ecosystem management. Compared to mature adults and the elderly, younger adults showed less understanding and appreciation of TEK.

Major factors contributing to the age-group variations include out-migration trends, the increasing modernization of agricultural activities, climate variability and change, and effects of perennial flood and droughts. The implication here is that people may be finding TEK ineffective in dealing with current social and environmental changes. Although the results from this research may not be a general indication of TEK’s status in other parts of Ghana, it does corroborate the generally observed trend of declining TEK in many societies. Nonetheless, the fact that communities and households have high regard for the use and application of traditional protected areas as a form for TEK for managing local ecosystems indicates the value placed on TEK by locals.

Based on the analysis conducted in this study, the impending loss of TEK of local communities in Northern Ghana should raise concern, along with the expected concomitant effects on the supply and availability of valuable ecosystem services. It is therefore imperative that national, regional, and local policies aimed at identifying, documenting, and implementing potent TEK are formulated to help safeguard ecosystems and improve livelihood systems, especially in rural areas of Ghana.

Acknowledgements

This paper evolved out of the doctoral thesis ‘Provisioning ecosystem services utilization and management in Northern Ghana: A community-based approach’ for the United Nations University Institute for the Advanced Study of Sustainability (UNU-IAS). We would like to thank Professor Toshiya Okuro and Dr Alexandros Gasparatos for their invaluable knowledge and inputs. The constructive feedbacks and suggestions from the three anonymous reviewers also contributed greatly to enhancing the quality of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Two main farm types exist in the study area: compound farms and bush farms. Compound farms, typically averaging 1.7 hectares per household, are present around household settlements; bush farms (average size being 3.1 hectares) are distant from settlements and are based on the bush fallow systems (Kranjac-Berisavljevic et al. Citation1999; Gyasi Citation2002).

References

- Abayie-Boateng A. 1998. Traditional conservation practices: Ghana’s example. Inst Afr Stud Res Rev. 14:42–51.

- Acheampong E, Ozor N, Owusu E. 2014. Vulnerability assessment of Northern Ghana to climate variability. Clim Chang. 126:31–44.

- Agrawal A. 1995. Dismantling the divide between indigenous and scientific knowledge. Dev Change. 26:413–439.

- Agrawal A. 2001. Common property institutions and sustainable governance of resources. World Dev. 29:1649–1672.

- Allison E, Badjeck M. 2004. Livelihoods, local knowledge and the integration of economic development and conservation concerns in the lower Tana River basin. Hydrobiologia. 527:19–23.

- Anane M. 1997. Religion and conservation in Ghana. In: Alyanak L, Cruz A, editors. Implementing Agenda 21: NGO experiences from around the world. New York: United Nations Non Liaison Services.

- Antwi EK, Otsuki K, Saito O, Obeng F, Gyekye AG, Boakye-Danquah J, Boafo YA, Kusakari Y, Yiran GAB, et al. 2014. Developing a community-based resilience assessment model with reference to Northern Ghana. J Integr Disaster Risk Manag. 4:73–92.

- Appiah-Opoku S, Hyma B. 1999. Indigenous institutions and resource management in Ghana. IKDM. 1:15–17.

- Atran S. 2001. The vanishing landscape of the Peten Maya Lowlands. In: Maffi L, editor. On biocultural diversity: linking language, knowledge, and the environment. Washington (DC): Smithsonian Institution Press; p. 157–174.

- Awedora AK. 2002. Culture and development in Africa with special reference to Ghana. Legon, Accra: Institute of Africa Studies. University of Ghana.

- Awumbila M, Ardayfio-Schandorf E. 2008. Gendered poverty, migration and livelihood strategies of female porters in Accra, Ghana. Norsk Geogr Tidsskr. 62:171–179.

- Berkes F. 1993. Traditional ecological knowledge in perspective. In: Inglis JT, editor. Traditional ecological knowledge: concept and cases. Ottawa, Canada: International Program on Traditional Ecological Knowledge and International Development Research Centre; p. 1–9.

- Berkes F. 2012. Sacred ecology. 3rd ed. London: Routledge.

- Berkes F, Colding J, Folke C. 2000. Rediscovery of traditional ecological knowledge as adaptive management. Ecol Appl. 10:1251–1262.

- Bernard HR. 2005. Research methods in anthropology. Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Walnut Creek, California, USA: Altamira Press.

- Boafo YA, Osamu S, Takeuchi K. 2014. Provisioning ecosystem services in rural savanna landscapes of Northern Ghana: an assessment of supply, utilization and drivers of change. JDR. 9:501–515.

- Boakye-Danquah J, Antwi EK, Osamu S, Abekoe MK, Takeuchi K. 2014. Impact of farm management practices and agricultural land use on soil organic carbon storage potential in the savannah ecological zone of Northern Ghana. JDR. 9:484–500.

- Carter MF, Hunter WC, Pashley DN, Rosenberg KV. 2000. Setting conservation priorities for landbirds in the United States: the partners in flight approach. AUK. 117:541–548.

- Colding J, Folke C. 2001. Sacred taboos: ‘invisible’ systems of local resource management and biological conservation. Ecol Appl. 11:584–600.

- Corbin A 2008. Sacred groves in Ghana; [ cited 2014 Nov 14]. Available from: http://www.sacredland.org/sacred-groves-of-ghana/

- Creswell JW. 2014. Research design: qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications Ltd..

- DeGeorges PA, Reilly BK. 2008. A critical evaluation of conservation and development in sub-Saharan Africa. Lewiston, New York, NY, USA: The Edwin Mellen Press.

- Derbile KE. 2009. Indigenous knowledge on soil conservation for crop production in Yua Community, Northern Ghana. Conference on International Research on Food Security, Natural Resource Management and Rural Development, Tropentag 2009. Germany: University of Hamburg.

- Diaz S, Demissew S, Carabias J, Joly C, Lonsdale M, Ash N, Larigauderie A, Adhikari RJ, Salvatore A, et al. 2015. The IPBES conceptual framework: connecting people and nature. Curr Opin Environ Sustain. 14:1–16.

- Dietz AJ, Millar D, Dittoh S, Obeng F, Ofori-Sarpong E. 2004. Climate and livelihood change in North East Ghana. In: Dietz AJ, Ruben R, Verhagen J, editors. The impact of climate change on drylands with a focus on West Africa. Dordrecht. The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; p. 149–172.

- Dorm-Adzorbu C, Ampadu-Agyei O, Veit P. 1991. Religious beliefs and environmental protection: the Malshegu sacred grove in Northern Ghana. Africa Centre for Technology Studies, Acts Press, Kenya. Washington, D.C: WRI.

- [TEEB] The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity. 2010. The economics of ecosystems and biodiversity: Ecological and Economic Foundations. P. Kumar, editor. London: Earthscan.

- Elias D, Rungmanee S, Cruz I. 2005. The knowledge that saved the sea gypsies. World Sci. 3:20–23.

- Eyssartier C, Ladio A, Lozada M. 2011. Traditional horticultural knowledge change in a rural population of the Patagonian steppe. J Arid Environ. 75:78–86.

- Fairhead J, Leach M. 1998. Reframing deforestation: global analysis and local realities. Studies in West Africa. London and New York: Routledge.

- Ghana Meteorological Agency. 2015. Compiled from climatic data records provided. Ghana Meteorological Agency Headquarters, Accra, Ghana, June 2015.

- Ghana Statistical Service. 2013. 2010 Population and housing census: demographic, social, economic and housing characteristic. Accra, Ghana: Ghana Statistical Service.

- Gibson CC, Williams JT, Ostrom E. 2005. Local enforcement and better forests. World Devel. 33:273–284.

- Gómez-Baggethun E, Mingorria S, Reyes-García V, Calvet L, Montes C. 2010. Traditional ecological knowledge trends in the transition to a market economy: empirical study in Donana natural areas. Conserv Biol. 24:721–729.

- Gómez-Baggethun E, Reyes-García V. 2013. Reinterpreting change in traditional ecological knowledge. Hum Ecol. 41:643–647.

- Gyampoh BA, Idinoba M, Amisah S. 2008. Water scarcity under a changing climate in Ghana: options for livelihoods adaptation. Development. 51:415–417.

- Gyasi EA. 2002. Farming in northern Ghana. ILEIA Newsl. 11:23.

- Hens L. 2006. Indigenous knowledge and biodiversity conservation and management in Ghana. J Hum Ecol. 20:20–30.

- Kingsbury N. 2001. Impacts of land use and cultural change in a fragile environment: indigenous acculturation and deforestation in Kavanayen, Gran Sabana, Venezuela. Interciencia. 26:327–336.

- Kranjac-Berisavljevic G, Bayorbor TB, Abdulai AS, Obeng F, Blench RM, Turton CN, Boyd C, Drake E. 1999. Rethinking natural resource degradation in semi-arid sub-Saharan Africa: the case of semi-arid Ghana. Tamale, Ghana & ODI, London, United Kingdom: Faculty of Agriculture. University for Development Studies.

- Liu J. 2006. Traditional ecological knowledge and implication to development from anthropological perspective. Chin Agric Uni J. 2:133–141.

- [MA] Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. 2005. Ecosystems and human wellbeing: synthesis. Washington DC: Island Press.

- Millar D. 2003. Forest in northern Ghana: local knowledge and local use of forest. Copenhagen: Sahel-Sudan Environmental Research Initiative.

- Millar D. 2004. Shrines and groves: bio-cultural diversity and potential environment management. Cantonments, Accra, Ghana: Communication and Media for Development.

- Molnar Z. 2012. Classification of pasture habitats by Hungarian herders in a steppe landscape (Hungary). J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 8:1–18.

- Ntiamoa-Baidu Y. 1995. Indigenous vs introduced biodiversity conservation strategies: the case of protected areas systems in Ghana. African Biodiversity Series. Washington: The Biodiversity Support Program.

- Nyong A, Adesina F, Elasha B. 2007. The value of indigenous knowledge in climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies in the Africa Sahel. Mitig Adapt Strat Glob Chang. 12:787–797.

- Ormsby AA, Bhagwat AS. 2010. Sacred forest of India: a strong tradition of community-based natural resource management. Environ Conserv. 37:320–326.

- Parrotta JA, Trosper RL, editors. 2012. Traditional forest-related knowledge. Sustaining communities’ ecosystems and biocultural diversity. Dordrecht, Heidelberg, London, New York: Springer.

- Ranganathan J, Daniels R, Chandran M, Ehrlich P, Daily G. 2008. Sustaining biodiversity in ancient tropical countryside. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 105:17852–17854.

- Reyes-Garcia V, Vadez V, Byron E, Apaza L, Leonard WR, Pérez E, Wilkie D. 2005. Market economy and the loss of folk knowledge of plant uses: estimates from the Tsimané of the Bolivian Amazon. Curr Anthropol. 46:651–656.

- Sarfo-Mensah P, Oduro W. 2010. Changes in beliefs and perceptions about the natural environment in the Forest-Savanna transitional zone of Ghana: the influence of religion. In: Gianmarco IPO, editor. Global challenges series. Nota Di Lavoro. Milano (Italy): Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei. [cited 2014 Nov 13]. Available from: http://ageconsearch.umn.edu/bitstream/59386/2/NDL2010-008.pdf.

- Sinclair SL, Walker DH. 1999. A utilitarian approach to the incorporation of local knowledge in agroforestry research and extension. In: Buck LE, Lassoie JP, Fernandes E, editors. Agroforestry in sustainable agricultural systems. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press LLC; p. 245–275.

- Songsore J. 2011. Regional development in Ghana: the theory and reality. Accra: Woeli Publishing Services.

- Strauss AL, Corbin JM. 1998. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory, 2nd ed. London: Sage Publications.

- Takeuchi K. 2010. Rebuilding the relationship between people and nature: the Satoyama initiative. Ecol Res. 25:891–897.

- Tengo M, Johansson K, Rakotondrasoa F, Lundberg J, Andriamaherilala JA, et al. 2007. Taboos and forest governance: informal protection of hotspot forest in southern Madagascar. AMBIO. 36:683–691.

- Tongco M. 2007. Purposive sampling as a tool for informant selection. Ethnobot Res Appl. 158:147–158.

- Turner NJ, Berkes F. 2006. Developing resource management and conservation. Hum Ecol. 34:475–478.

- Turner NJ, Turner K. 2008. ‘Where our women used to get the food’: cumulative effects and loss of ethnobotanical knowledge and practice; case study from coastal British Columbia. Botany. 86:103–115.

- Ulluwishewa R, Roskruge N, Harmsworth G, Antaran B. 2008. Indigenous knowledge for natural resource management: a comparative study of Maori in New Zealand and Dusun in Brunei Darussalam. GeoJournal. 73:271–284.

- United Nations. 1992. Convention on biological diversity (with Annexes). Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: United Nations.

- Usher P. 2000. Traditional ecological knowledge in environmental assessment and management. Artic. 53:183–193.

- van De Geest K. 2004. ‘We’re managing!’ climate change and livelihood vulnerability in Northwest Ghana. Leiden, The Netherlands: African Studies Centre.

- Whitehead A. 2006. Persistent poverty in North East Ghana. J Dev Stud. 42:278–300.

- World Bank. 2011. Global facility for disaster reduction and recovery (GFDRR) country report Ghana. Washington (DC): World Bank. [ cited 2014 Oct 13]. Available from: http://gfdrr.org/ctrydrmnotes/Ghana.pdf.