ABSTRACT

Despite the resurgence internationally of strikes in recent years, studies on the temporality of strike waves within a long-wave perspective has been marked by silence in the literature. This paper revisits the debate on the veracity of long-wave theory to explain the temporality of upsurges in strike activity and the disputes on the measurement of strike waves from an international perspective. The paper applies long-wave theory to South Africa, which is a new contribution and proposes a new quantitative approach to examine the long-term patterning of strikes. This study finds that the predictive power of long-wave theory—that an escalation of the class struggle unfolds around the peaks and troughs of economic long waves—holds throughout the period 1886–2022. This paper makes a new finding that long waves of strikes display a countercyclical patterning to long waves of capitalist development, providing proof of the relative autonomy of the class struggle from long waves.

Introduction

Long-wave theory has been used to examine and theorise the temporality of strike waves and economic turning points of long waves (Trotsky Citation1921, Citation1941; Hobsbawm Citation2015; Mandel Citation1980, Citation1995; Cronin Citation1980; Screpanti Citation1984, Citation1987; Silver Citation1992, Citation1995; Dockes and Rosier Citation1992; Franzosi Citation1995; Kelly Citation1997). The proposition of long-wave theorists is that the rise and decline of significant periods of labour mobilisation follow predictable patterns that are closely synchronised with the long-term fluctuations (40–60 years) of the capitalist economy. Despite the resurgence of strikes in recent years, studies on the temporality of strike waves within a long-wave perspective has been marked by silence in the literature.

This paper revisits the debate on the veracity of long-wave theory to explain the temporality of the upsurges in strike activity. Mainstream economists were sceptical of long waves of capitalist development as econometric techniques in use failed to detect long waves, because they were designed to detect business cycle fluctuations. Long-wave theorists’ position was bolstered by Metz (Citation1992) breakthrough employment of a new econometric filter technique that detected long waves, providing a new consensus on the existence and periodisation of economic long waves. Wallerstein, in his closing remarks at the proceedings of the Long Wave Conference held in Brussels in 1989, put this conclusion eloquently:

The resistance to acknowledging the existence of “long waves”, is, when all is said and done, astonishing. All modern science presumes the normality of patterned fluctuations. No doubt there is more to reality than patterned fluctuations, but there seem to be no real phenomena that do not fluctuate in ways that can eventually be summarised empirically as patterns. (Wallerstein Citation1992, 339)

The literature on long waves has been primarily engaged in the application of quantitative techniques to prove the existence of long waves and their synchronisation with major upsurges in class struggle or strike waves. Long-wave theorists remained divided about the temporality of major upsurges in class struggle. The disagreement centred around whether strike waves tend to cluster around either the peaks or troughs of long waves of capitalist development, around both, or not at all.

Screpanti’s (Citation1987, 100) proposed solution to the quandary was to employ strike indices that measure strike intensity. Strike indices found in government statistics that can measure intensity and reveal the patterning of strikes are number of strikes or strike frequency (F), number of strikers or size (S) and days lost (D). Screpanti (Citation1987, 102) developed a sophisticated model combining the variables F, S and D into a composite variable of strike intensity using principal component analysis. Screpanti’s (Citation1987, 111) conclusion of his statistical procedure was that the most intense strike waves manifest around the peak of the long waves in 1869–1875, 1910–1920 and 1968–1974. Kelly’s (Citation1999, 88) review concluded that while Screpanti used sophisticated methods, the results of his study were very similar to studies (Jackson and Sweet Citation1979) with less-sophisticated methods.

Silver (Citation1992) criticised Screpanti’s statistical method as inadequate because measurements of strike intensity cannot be reduced to core economies and should integrate core and peripheral countries if an accurate picture of labour unrest temporality is to be observed. She furthermore criticised the use of government statistics as they did not exist for large time periods during the world wars. Using the World Labour Research Group (WLRG) database, Silver’s (Citation1992, 285) research indicated that major upsurges in labour unrest took place in 1889–1890, 1911–1912, 1919–1920 and 1946–1948, most of which did not conform to long-wave theory propositions of high levels of class struggle intensity around the peak of long waves. Rather, for Silver, the periods of intense class struggle are closely associated with the world wars, where a breakdown of the old imperialist hegemony occurred, while declining in the periods of the new emerging hegemony. Surprisingly, the WLRG database did not show the well-known period of 1968–1972 as a period of intense labour struggle, which in turn raises questions about the adequacy of the WLRG database.

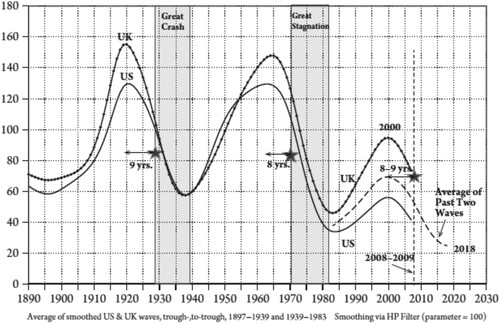

Mandel (Citation1995, 126) derived his general class struggle trend from historical knowledge and not from empirical data. Mandel (Citation1995, 126) highlighted that Gattei (Citation1989) had used the number of days lost to measure strike waves in four European countries. The peaks in days lost occurred in 1893, 1905–1906, 1911–1913, 1919–1921, 1926, to which Mandel added France 1936–1945, Spain 1912–1937 and Germany 1933–1948. However, the challenge of measuring the intensity of the strike waves was still not resolved ().

Figure 2. Long waves in European class struggle and long waves in economic growth. Source: Mandel (Citation1995).

Kelly (Citation1999, 89), who carried out a comparative study of various long-wave theorist studies, concluded that strike waves occur towards the end of the upswing of the long wave (1869–1875, 1910–1920, 1968–1974) and less-intense strike wave towards the end of the downswing of the long wave (1889–1893, 1935–1948). This was in contradiction to Mandel, who argued that the most intense strike waves occur on the downswing of the depressive long wave.

Key to understanding the variation of results of the various long-wave theorists is that the authors do not use the same sample of countries within which to test their various methodologies, giving rise to a variation of results. Furthermore, there is no consensus on the kinds of data to use to study strike waves and upsurges in class struggle. Silver’s WLRG database is based upon hegemonic newspapers, which led her to incorrectly conclude that there was no major upsurge by workers in the 1968–1972 period. Screpanti’s use of government strike statistics had a serious shortcoming as the statistics were not adequately captured during the world wars, resulting in the omission of major upsurges of strike waves around the troughs of long waves. Kelly’s review of the works of long-wave theorists was limited as he interpreted other authors’ works to draw his conclusions on the temporality of major upsurges in labour struggle. While Mandel located the temporality of strike waves around both the peaks and troughs of long waves, questions remain as to the adequacy of his method (which relied on observation rather than empirical evidence), exacerbated by the absence of southern countries from his analysis.

This article fills a lacuna of previous methods by long-wave theorists to discover the temporal patterning of strike waves and upsurges in the class struggle and its relationship to economic long waves of capitalist development. I introduce the concept of “long waves of strikes”, which refer to the “semi-autonomous, macro-historical fluctuations of strikes over the long-term asymmetrical curve of capitalist development” (Cottle Citation2020, 14). Strikes are semi-autonomous because while there is a tendency for strikes in South Africa to be pro-cyclical, strike waves can also be triggered by economic crisis, political and social factors (Cottle Citation2017, 147–167). The article provides a new empirical method that can illuminate what I call long waves of strikes and its distinct macro-historical patterning, which runs countercyclical to economic long waves.

Strike data in South Africa

During apartheid (1948–1994), quantitative data on strikes was published by the Department of Manpower, the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), the Indicator Project South Africa, the Industrial Relations Research Unit and Andrew Levy Industrial Relations Data (IRD). Since the first democratic elections in South Africa in 1994, strike data have been published by the Department of Labour, the International Labour Organisation and the Development Policy Research Unit. Strike data for the apartheid period exclude many strikes, as only those reported to the Department of Manpower were counted (Howe Citation1984; Levy Citation1985). Building on Backer and Oberholzer’s (Citation1995) strike data covering 1910–1994, van der Velden and Visser (Citation2006) reviewed available data from 1900 to 1998 to complete the time series and noted missing data for the following years: 1908–1909, 1925 and 1940–1941.

Strike data since 1999 is extensive when the Department of Labour began publishing annual Industrial Action Reports that include both strikes reported by employers and all forms of industrial action reported in the press. Nonetheless, in order to ensure comprehensiveness, this study employed secondary sources, such as the Union of South Africa Official Yearbook, academic works in labour and economic history, the South African Institute of Race Relations, Andrew Levy & Associates, and archival newspapers to augment the official data sets. The data set has been updated from 1886 and includes the missing strike years of 1886–1890, 1893–1903, 1905–1909, 1940–1941 and 1995–1998.

Three aggregate measures of strikes are used in the analysis of the strike data: number of strikes (F), number of workers involved (S) and number of days lost (D) to determine whether there is consistency in the combination of these variables of strikes making up strike waves. In line with an inductive approach, the strike data are used to identify the presence of strike waves for the entire historical period under review, shedding new light with a timeline and count of strike waves in South Africa.

Measuring strike waves in South Africa

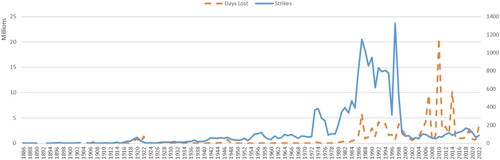

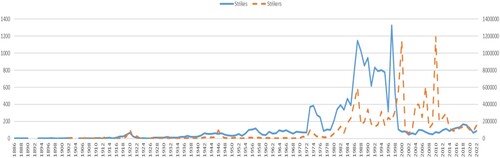

In examining long waves of strikes in South Africa for the period 1886–2022, the uneven nature of fluctuations in strike data (specifically F, S and D) is depicted visually ( and ). There is no uniformity displayed between the number of strikes, days lost or number of strikers, with the strike variables appearing to fluctuate independently of each other. Further, none of the variables (F, S or D) display any regularity or visible patterning, with ebb and flow evident across the historical timeline.

Figure 3. Days lost & strikes (1886–2022). Source: Cottle, E. (2020, 212), updated Annexure 1: Historical timeline of strikes in South Africa 1897–2017.

Figure 4. Strikes and strikers (1886–2022). Source: Cottle, E. (2020, 212), updated Annexure 1: Historical timeline of strikes in South Africa 1897–2017.

At this stage, using strike statistics to visualise strike dynamics does not yield much useful insight into the patterning of strikes and strike waves in South Africa. Moreover, using existing quantitative methods to calculate strikes waves absurdly indicates that no strike waves occurred in South Africa in the late 1980s and 1990s. Both the visual presentation and labour history paint a different picture: these years were characterised by intense, sometimes turbulent strikes and a general increase in the level of class struggle. Silver (Citation2003, 195), borrowing from Shorter and Tilley (Citation1974), defines the year in which the number of strikes is at least 50 per cent higher than the mean of the previous five years as the year in which a strike wave commences. Franzosi (Citation1995, 259–261) on the other hand argues that this operational definition of a strike wave is inadequate, as the 1969 Italian strike would not qualify as a wave year, despite its historical peak in the number of days lost. Similarly, Koenker and Rosenberg (Citation1989, 182) argue if the operational definition of a strike year is applied to the February 1917 Revolution in Russia, it would not be considered as a wave year as there was a peak in the number of strikers. On the other hand, Beittel’s (Citation1995, 93) findings suggest that indicators of the number of working days lost as established by Bordogna and Provasi (Citation1979) can also be used to identify strike waves. In short, workers strikes can peak in F, D and S and are thus equally important to measure as strike wave years. Consequently, it must be deduced that the measure of strike waves developed by Shorter and Tilly (1974) and Bordogna and Provasi (1979) that a wave year is calculated as at least 50 per cent of the mean of the preceding five years are only applicable in the European context where strike wave years are shorter than in a southern country like South Africa. This called for the development of a measure that could capture a 20-year period (1980–1999) of intense strike action. After examining several variations, the only measure to capture this period adequately is when the number of strikes, days lost and strikers in that year exceed the mean of the preceding 20 years by at least 50 per cent. Only in this way would the measurements identify strike waves within long periods of intense strike action. By adding this measure, there were 54 strike wave years in South Africa between 1886 and 2022. The approach taken was not to accept the empirical results as given but verified in the works of labour history and other secondary sources. The strike wave years in South Africa are 1907, 1910–1911, 1913–1914, 1916–1920, 1922, 1934, 1937, 1941–1947, 1954–1957, 1961, 1964, 1971–1974, 1980–1982, 1984–1990, 1992–1994, 1997–2000, 2005–2007, 2010, 2012, 2014 and 2022. This approach thus illuminates the strike data meaningfully and provides a full historical timeline of strike waves in South Africa. However, there appears to be no discernible patterning with peaks, ebbs and flows unevenly spread across the historical timeline. Furthermore, as there is a lack of definitional clarity of turning points, this further complicates the analysis to which we now turn.

Labour turning points

Long-wave theorists generally do not explicitly specify labour turning pointsFootnote1 but rather locate “class struggle cycles” between economic turning points (peaks and troughs) of long waves. Among these theorists are those who, while not distinguishing between different types of labour turning points, do refer to labour turning points (Cronin Citation1980; Kelly Citation1999), but in a limited way that relate to ruptures in mobilisation, breakthroughs in forms of trade union organisation, changes in ideology and industrial relations. Long-wave theorists have neither examined the combined effect of the escalation of the class struggle, the characteristics of the structural effects of strike waves and the types of labour turning points, nor explained how the theory accounts for the general movement towards the intensification of strikes and strike waves. While the trigger of initial strike waves is a clustering of cost-cutting technological innovations and changes to the labour process, it is the combination of other dynamics—business cycle fluctuations, long-standing grievances, levels of mobilisation capacity and political factors that culminate in strike waves and have structural effects—that intensify the class struggle (Cottle Citation2020, 40).

In contrast to long-wave theorists, this paper argues that labour turning points are those events which demonstrate the power of strikes to create upheaval in the established order. This is a consequence of the extraordinary amount of pressure on the economic, political and social system that strikes can generate, which, under the right conditions, could lead to structural change such as the reconfiguring of the industrial relations system, the economy or political system. Thus, I argue that while ruptures (structural effects) readily occur, the nature and extent of the resultant structural change allows two distinct labour turning points, which bear a direct relationship to the long-term patterning of long waves, to be differentiated. The initial turning point strike waves (ITP) are those that signal that the class struggle has begun, the structural effects of which mainly lead to increased levels of labour mobilisation and changes in industrial relations. The other, a historical turning point strike wave (HTP), which ushers in political reforms, revolution or defeat of the working class, leading to a political turning point (PTP). Political turning points typically signal changes in political representation and economic and social policy. In exceptional circumstances, there are also revolutionary strike waves, occurring between ITPs and HTPs, such as those between 1971 and 1990 that seek to challenge the continued existence of the capitalist social order. This general movement of intensification of strikes follow a predictable pattern and is expressed schematically as ITP → HTP → PTP (Cottle Citation2020, 3–5).

South Africa’s long-wave periodisation

Wallerstein (Citation1992, 342) argued that “many long-wave analysts work with a model that, unless a country is ‘industrialised’, with a large, wage earning-proletariat, there can be no real cycles. I challenge this”. By employing a conceptual model based on South Africa’s economic history to determine the patterning of the third long wave () and a spectral analysis for the fourth and fifth long waves (), this study supports Wallerstein’s challenge to long-wave theorists, that it is indeed possible for less-industrialised countries to exhibit long-wave patterning.Footnote2 The approach adopted in this study combines the work of economic and labour history (Katzen Citation1964; Houghton Citation1969; Davies Citation1979; Padayachee Citation1985; Alexander Citation2000; Bell Citation2001; Feinstein Citation2005) with the results of the econometric study () to identify more precisely the temporal patterning of strikes and strike waves.

Table 1. Long waves of capitalist development (first to sixth wave).

What and show is that the long-wave patterning of a less-industrialised country such as South Africa is indeed similar to that of industrialised countries. South Africa’s long-wave patterning begins (as far as this study has determined) with the third long wave in 1886, almost 100 years after the first long wave in industrialised countries in 1790. South Africa’s third long wave (1886–1939) is 53 years; the fourth long wave (1939–1990) is 51 years, and the fifth long wave (1990–2019?) is 29 years (which is still underway). The economic long wave during the apartheid period is clearly longer than the long wave in the post-apartheid period. The possible explanation for this is that struggle against apartheid deepened the economic and political crisis, which dragged out the length of the downswing by 8 years in which South Africa missed out on the early phase of the global recovery of the 1980s.

If we use the periodisation of Kelly (Citation1999, 89) that the most intense strike waves took place towards the peak of long waves (1869–1875, 1910–1920, 1968–1974) then they are clearly aligned with the peaks of the second, third and fourth long waves. In this case, South Africa’s strike waves also align around the peak (but move down the depressive economic wave) of the third long wave (1907, 1910–1911, 1913–1914, 1916–1920, 1922) and fourth long wave (1964, 1971–1974). The distinction, however, from the northern countries is that strike waves in South Africa continued and intensified as revolutionary waves and intensified towards and around the trough of the economic long wave in 1990.

Likewise, if we consider Kelly’s evidence of strike waves towards the end of the downswing (1889–1893, 1935–1948) then here too South Africa strikes waves, except for 1889–1893 (as this period marks the beginning of the industrial revolution) occurred in 1934, 1937 and 1941–1947—the period of World War II. In all countries, the post-war period marked political turning points with the advent of social democracy in Europe, and the communist revolutions and anti-colonial movements in the South.

Using Shaikh’s (Citation2016) recent and updated long-wave study (), Mandel’s argument appears to hold. The international character of strike waves in the early twenty-first century align with the intensification of class struggles towards the end of the depressive long wave. The temporality of the historical turning point strike waves (HTP) that clustered towards the end of the depressive long wave with major general and mass strikes in Portugal, Spain, Greece, China, United States, the United Kingdom, Iceland, Turkey, Egypt, Tunisia, Germany, France, India, Cambodia, Brazil (Gallas and Nowak Citation2016) and South Africa between 2005 and 2022 demonstrate the veracity of the explanatory and predictive power of long-wave theory. The HTP gave way to PTP, the result of which has been a global shift to the right.Footnote3

However, this study is interested in the precise timing of temporal upsurges of strikes in South Africa, which would allow an examination of the predictability of the patterning of strikes. To allow for precision of temporality this study employs a cross-spectral analysis.

Cross-spectral analysis

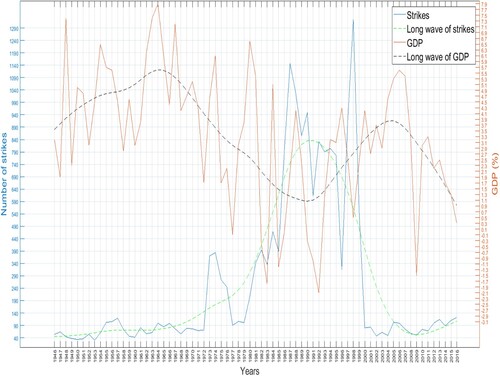

A prior study (Cottle Citation2017) of the period 1960–2016 found a strong correlation between strikes and the business cycle in South Africa, which indicates that increases in strike frequency and major upsurges in strikes have a tendency to increase on the upswing of a business cycle rather than the downswing (). This supported the findings of Williams (Citation2017) for the period 2003–2014, who also found that strikes had a cyclical patterning. In other words, workers go on the offensive on an upswing of the business cycle where workers demand an improvement in their living and working conditions and become defensive when workers resist changes introduced by the capitalists worsening living and working conditions during a downswing of the business cycle (Cottle Citation2022, 105). In figure 6 below we can see that strikes move in a similar pattern to business cycle fluctuations, which is considered pro-cyclical.

Figure 5. Cross-spectral of long waves of growth and long waves of strikes (1946–2016). Source: Cottle Citation2020, 223.

At the Brussels conference of 1989, Metz and Stier (1992) used an econometric method called spectral analysis to detect economic long waves. However, the conference completely ignored an analysis of the use of spectral analysis to either detect the patterning of strikes or the relationship between strikes and economic long waves. This left a significant gap in the scientific study of the patterning of strikes and upsurges in the class struggle. Spectral analysis is a technique that allows us to discover cyclical patterns of variables and their interrelation, which is difficult to identify based on purely descriptive methods. To perform spectral analysis, the data must be transformed from the time domain to the frequency domain (Casutt Citation2012, 20). For example, the time domain in this study uses gross domestic product (GDP) aggregate data from 1946 to 2016, which is then converted to a frequency domain, which is then able to pick up the economic long-wave patterning. To establish the patterning of strikes and its co-movement within long waves of capitalist development, a cross-spectral analysis of GDP and strikes is conducted (figure 5). The applied method thus reveals the cyclical structure of the strike series in a country during the investigation period, and further explores this structure in interaction with long waves of capitalist development. This is called “cross-correlation”, which can be simply defined as a technique that can provide the common relationship between two or more signals. The GDP data are derived from the South African Reserve Bank, and strike data from various sources as outlined earlier.

The results and discussion

The GDP and the strikes data (1946–2016) represent the two time-domain signals. We want to identify whether any correlation exists between them. The findings show that there is a strong correlation between GDP and the strike data between 1946 and 1951. Between 1952 and 1959 the strength of the correlation decreases and from 1960 to 2016 there is no correlation between GDP and strikes. Considering the results, the cross-spectral analysis reveals that there is no correlation between the patterning of long waves of GDP and long waves of strikes over a period of 70 years (Cottle Citation2020, 228).

The results of the cross-spectral analysis that there is no correlation between long waves of strikes and economic long waves are perplexing as they contradict findings of studies on the shorter business cycle (which in the long run make up the economic long wave). Do the results of the cross-spectral analysis contradict the conclusion of long-wave theorists of a close relationship between long-term fluctuations of economic long waves and the temporality of major upsurges in the class struggle? Was Silver correct and Mandel incorrect?

South Africa’s long-wave patterning

While the short-term patterning of strikes in South Africa is cyclical, the patterning of long wave of strikes are countercyclical (: green dotted line) to the economic long wave fluctuations of the capitalist economy (black dotted line). By countercyclical is meant a patterning of strikes opposing the trend of a business or economic cycle. The long-term movement of strikes depicts a patterning with lower rates of strikes on the upswing of the expansive phase of the economic long wave with an increasing frequency of strikes on the downswing phase of the economic long wave. In other words, the long waves of strikes patterning follow an opposing trend to that of economic long waves. The long wave of strikes covers a length of 70 years (1946–2016). In this period there are two downturns and one complete upturn and one partially complete upturn in strikes. In the long run the partial upturn of long wave strike action from 2005 is moving in an upward trajectory in a similar pattern as the previous long wave of strikes. This is a new discovery, which contradicts Mandel’s European class struggle curve () which displays a pro-cyclical movement that mirrors the patterning of economic long waves. However, while Mandel’s depiction of his class struggle cycle is incorrect, the scientific depiction of long waves of strikes in this article provides proof of Mandel’s fundamental proposition of the “relative autonomy of the class struggle cycle from long waves”. As indicated before, the pro-cyclability of strikes expresses a tendency and not a law as strikes are also impacted on by other factors. As Mandel (Citation1995, 38) explains,

When we speak about a relatively autonomous long-term cycle of class struggle (strongly determined by the historical effects of cumulative working-class victories and defeats in a series of key countries), we do, of course, mean just that and no more. No Marxist would deny that the subjective factor in history (the class consciousness and political leadership of basic social classes) is in its turn determined by socioeconomic factors.

Figure 6. Real GDP growth rate and strike frequency 1960–2014. Source: Cottle Citation2017, 154.

This is clearly visible around the peak of the economic long waves of 1964 and 2005 where the long wave of strikes begins to slope downwards indicating an intensification of class struggle (figure 5). Silver’s (Citation1992, 289) finding that major upsurges of the class struggle also occur along the expansive economic long wave is validated by the South African experience. In 1946 the African Mine Workers strike took place on the expansive economic long wave including several strike waves in the 1950s. Similarly, there are many strike waves in the 1990s with the largest number of strikes in South African history recorded in 1997, eight years before the peak of the economic long wave is reached. In other words, upsurges in the level of class struggle occur along both the expansive and depressive economic long wave. Thus, Silver’s criticism of long-wave theorists’ Eurocentric perspective that it is insufficient to measure strike intensity in core countries is correct as the patterning of strike waves or upsurges in the class struggle in southern countries are not the same. However, despite Silver’s argument, the results of the cross-spectral analysis show that the most intense strike waves still occur around the trough of the economic long wave (). Thus, while Silver is correct about upsurges along the expansive economic long wave, the South African case at the same time confirms Mandel’s theory that class struggle intensifies along the depressive long wave.

South Africa’s long wave of strikes

The periods where workers adopt a more radical approach to struggles are episodic and synchronise with the long-term movements of capitalism when the general rate of profit declines. The trigger for large-scale disruptions of production by workers becomes generalised when capitalists introduce labour-saving technologies and cost cutting across industry. These changes undertaken directly impact on changes in the labour process, which generally includes an intensification of work in order to increase productivity. These changes may include an extension of working hours, additional shifts and reorganising the division of labour to increase the number of tasks of workers.

In South Africa, the introduction of cost-cutting technological innovation, changes in the labour process and general cost cutting occurred between five and seven years before the peak of long waves, resulting in a clustering of strikes across industries and a general intensification of the class struggle. This occurred around the peak of the third long wave in 1913, the fourth long wave in 1964 and the fifth long wave in 2005.

Third long wave (1886–1939)

This period marks the discovery of diamonds and gold, which spurred the Industrial Revolution in South Africa and transformed South Africa from an agrarian country into a modern capitalist state. The long economic upswing coincided with a period of recovery in Britain, Europe and the USA, with the inflow of finance into the mining industry and large-scale immigration of white miners, who viewed African migrant labour as their competitors (Katzen Citation1964, 64–65). As deep-level mining was costly, the initial effort at cost maximisation was to ensure a steady flow of coerced, cheap African and Chinese labour and the enforcement of a colour bar on the mines (Johnstone Citation1976, 3, 19–20; Davies Citation1979, 53). During this time both white workers and black workers had engaged in strikes and Africans had frequently used the tactic of desertion back to the labour reserves. In 1907, six years before the peak of the economic long wave, 6400 white miners struck against the work intensity of a three-drill system, wage cuts, changes in the division of labour in relation to the ratio of African and white workers and the implication of the new system for their health. These factors combined and culminated in the initial turning point strike wave of 1907 registering 288,000 days lost to production (Cottle Citation2020, 62). The general strike was suppressed, allowing mining capital “to bring about a reorganisation of wages in a few months, which under normal circumstances would take years to achieve” (Shear Citation1994, 18). The structural effects of the general strike revealed that a new power of workers had emerged that provided the impetus to organise unions on an industrial basis (Harris Citation1991, 50–51). Furthermore, in 1908 the Industrial Disputes Prevention Bill was introduced, providing for the first attempt institutional industrial conflict (Yudelman Citation1984, 85) and the 1911 Mines Act provided for a comprehensive codification of the colour bar and conditions of work on the mines (Wilson Citation1972, 8). By the time the 1913–14 strike wave took place the clustering of radical cost-cutting measure were introduced across industrial sectors, marking the entry of workers on a mass scale with about 20,000 workers on strike each year. These include a mass strike by Indian indentured workers, African and white miners in gold and coal, and railway and harbour workers. The strike was in response to measures such as cuts in wages, cutting Saturdays as a holiday, retrenchments and the increasing rock drill operations from two to five. With no resolution of the grievances of workers, the class struggle intensified with the commencement of the downswing of the economic long wave, culminating in the strike waves of 1916–1920 which occurred on an upswing of the business cycle (Cottle Citation2020, 71–75). This wave was larger than the 1913/1914 strike wave and fuelled by inflationary pressures. In 1920, 71,000 unorganised African miners went o strike, with days lost reaching 839,415, more than double that of 1907. The African miners had long-standing grievances related to unfair treatment due to the colour bar and stagnated wages despite being employed in semi-skilled work. The strike signalled a distinct change in capital–labour relations as it was the first time mining capital was severely challenged by African miners. The structural effects also saw new forms of labour and political opposition with the South African Native National Congress (later renamed ANC) was formed in 1912 on the peak of the long wave and the Industrial & Commercial Workers’ Union (ICU) was launched in 1918 (Cottle Citation2020, 79). By 1922 there was a sharp drop in the gold price which prompted mining capital to undertake further cost cutting to maintain profitability (Wilson Citation1972, 10). Amidst a depression, white workers were hesitant to strike as retrenchments had engulfed both manufacturing and agriculture. The return of Afrikaner workers from World War I seeking employment further eroded the power of the miners. Mining capital attempted to negotiate further cost cutting instead of imposing its will for fear that a defensive strike action could result in explosive industrial action (Cottle Citation2020, 80). A pattern now emerges of the role of long-standing grievances of the miners who had been battling mining capital since 1907. The miners had accumulated lots of experience in industrial conflict and through an augmented executive were able to unite gold, coal, energy and engineering workers in a general strike led by shop steward committees and Afrikaner commandoes. In this case what started as an industrial relations dispute turned into the famous Rand Revolt in which 250 people were killed (Wilson Citation1972, 10). This was a historical turning point (HTP). The structural effects included far-reaching economic setback for the miners including wage cuts, retrenchments and a radical reorganisation of the labour process. Legislatively, the colour bar was annulled in the Mines and Works Act of 1923 and the Industrial Conciliation Act in 1923 suspended the automatic right to strike. For the first time capital was able to secure the conditions required to ensure a sustained increase in the conditions for a rapid increase in the rate of profit, a pre-condition for the economic long wave to move into an expansionary wave. While the 1922 Rand Revolt was a defeat, white workers used their associational power to defeat the South African Party, which allied with mining capital to ensure a victory of a National Labour pact in a general election—a political turning point (PTP). The outcome was the Colour Bar Act of 1926, which ensured the long-term security and privileges of white workers (Cottle Citation2020, 82). There is little information available on the strike waves of 1934 and 1937, which may be attributed to a seven-week strike in the furniture industry in the Transvaal and the series of strikes by African workers in Durban (Davies Citation1979, 263).

Fourth long wave (1939–1990)

The advent of World War II (1939–1945) stimulated the country’s systems of technological innovation, allowing for the rapid expansion of the manufacturing sector (Scerri Citation2016, 172), and by 1943 manufacturing outstripped mining’s contribution to GDP (Feinstein Citation2005, 123–125). The massive profits accrued ensured radical technological innovation in electrical motors, ship repair, construction methods, engineering and machine tools greatly assisted by the state Industrial Development Corporation, resulting in mass urbanisation by all sections of the population (Houghton Citation1969, 239).

With the upswing of business cycle there was an increase in strike activity resulting in the 1941–1945 strike wave. Most of these strikes were in the manufacturing sector, which included workers across racial backgrounds and gender (Alexander Citation2000, 44, 128; Padayachee et al. Citation1985, 122). The prominent role of African workers in these strikes and the growth of trade unionism created uncertainty amongst employers. While black workers in general had moved to fill semi-skilled positions, white workers still occupied 85 per cent of skilled jobs.Footnote4 Most of the increases in F, S and D are attributed to the offensive 1946 African miners’ strike and the white builder strike of 1947. In contrast to manufacturing workers, mining workers faced an economic contraction. The grievances of the African miners were long-standing, related to a crisis of reproduction in the reserves and on the mines where the war effort created food shortages resulting in strikes, riots and protests (O’Meara Citation1975, 159). Compounding their predicament was the reliance of government on mining, which contributed significantly to its social capital contributions. The 1946 general strike was therefore perceived as a direct threat to government coffers including the costs of the government commissioning of new Free State Mines (Katzen Citation1964, 58, 93; Houghton Citation1969, 103). Against rising discontent of the mine workers, the African Mine Workers Union (AMWU) called a general strike of 71,000 workers, affecting 21 of 47 mines. Within four days the strike was crushed due to the tenuous organisation of the strike (Cottle Citation2020, 95). This questions Moodie’s (Citation1986, 28) assessment of a very high level of organisation on the mines.

The 1947 strike wave was primarily driven by the nine-week white builders strike with 28,848 workers participating, resulting in 716,105 days lost to production. In contrast to the African miners, the offensive white builders general strike took place on an upswing of the business cycle owing to a boom in the building industry related to the development of the new mines, new towns, housing, railways and powerlines led by the state (Wilkinson Citation1981, 10; Bell Citation2001, 32). The white builders were threatened by the increased training and employment of African artisans in the government social infrastructure programme. The outcome of the white builder’s strike was the dismissal of thousands of African building workers. The grievances of the white builders were long-standing owing to a drop in real wages during the war including their demand for a 40-hour week (Alexander Citation2000, 108–109). It is the combined effects of the African miners and the white builders’ strike within a racialised social formation that gave way to a political turning point, the victory of the National Party in 1948 and the creation of an apartheid society (Cottle Citation2020, 99).

As the post-war period was generally a period of profitability, the number of strikes increased during the 1950s while the number of strikers and days lost to production declined significantly, which is consistent with business cycle explanations. However, these lower levels of resistance by black workers were also a reflection of increased levels of repression, which targeted trade union offices with closure and unionist with arrests. Despite the difficulties, the strike waves between 1954 and 1957 were able to generate increased trade union membership with the South African Congress of Trade Unions being launched in 1955, which formed a political alliance with the ANC. Henceforth the strikes, while economic in character, were increasingly politicised. This period is considered the period in the coming together of the economic and the political struggles in the forms of protests organised in the form of mass demonstrations, boycotts, defiance campaigns and strikes (MWT Citation1984). Despite the political character of this decade the brevity of the strikes and lower participation rates in strikes resulted in an increase in the racial wage gap and a general deterioration of living standards of Africans. The structural effects were felt in the economic sphere which allowed for an increasing rate of profit allowing for a “great boom” in the 1960s (Houghton Citation1969, 189–199). State repression had prevented the outflow of capital, with significant foreign investment for new gold mines, and the expansion of manufacturing with rapid technological advances (Bell Citation2001, 34; Feinstein Citation2005, 166–173).

Towards the peak of the economic long wave of 1964 () strikes increase at greater levels than the 1950s, with peaks in days lost in 1961 and 1964. The period of the 1960s was not a period of acquiescence as claimed by conventional characterisation (Bonner Citation1987, 55; Maree Citation1987, 2; Friedman Citation1987, 44). According to a statistical report by Shane and Farnham (Citation1985), the trigger causes of most of the strikes between 1960 and 1971 in South Africa ranked from highest to lowest are working conditions, wages, payments, and dismissals. It is significant that most strikes were attributed to working conditions. This indicates that employers were engaging in changes to the labour process that workers were resisting. Research and development increased rapidly towards the end of the expansionist long wave (in the mid-1960s) in the mining, manufacturing and agriculture sectors (Gelb Citation1991, 116–117). In this period there was significant “reorganisation of work as a result of automation” (Berger Citation1992, 266) and strikes increased from an average of 66 strikes in the 1950s to 74 strikes in the 1960s. The peak in days lost in 1961 was due to a three-day stayaway organised by the ANC and SACTU against the South African Republic (Bonnin Citation1987, 164) and in 1964 there were significant strikes in the textile industry where workers were challenging wage levels and a new 11-hour shift (Horrell, Horner, and Kane-Berman Citation1965, 266; Rand Daily Mail Citation1964, 1). In February 1971, just before the outbreak of the Durban strikes, the Garment Workers Industrial Union led a successful strike of 23,000 mainly Indian women at Currie’s Fountain in Durban (Rand Daily Mail Citation1971, 3). The 1971 strike wave registered as an S-wave with the average number of strikers in the past five years increased from just 3841 to 27,451, a 715 per cent increase in 1971 marking an initial turning point strike. Henceforth, the tempo of struggle increases with a wave of strikes across industries in 1972 which then culminate in the greater wave of proletarian disruption in Durban in 1973. After almost a decade of intense labour mobilisation the government announced the scrapping of job reservation laws, followed in 1979 by the legalisation of black trade unions (Friedman Citation1987, 150)—the structural effects. While the structural effects were economic, the context of apartheid gave them an overtly political character that “affected a far wider section of the population”, resulting in the Soweto Student Revolt of 1976 (Hirson Citation1979, 156).

The class struggle increased dramatically along the downswing of the economic long wave, culminating in the strike waves of 1980–1982 and 1984–1990. The average frequency of strikes in the 1980s was (F = 596) 233 per cent, number of workers (S = 214,432) 667 per cent and (D = 1,135,709) days lost was 1986 per cent higher, respectively, than the 1970s with a peak of 1148 strikes in 1987. The significantly high combinations of F, S and D reflect increases in organisational capacity, changes in political consciousness and increasing determination of workers to win their demands (Cottle Citation2023, 108). The strike dynamics of this period were shaped overall by the relatively autonomous political struggle, which overwhelmed economic considerations. Neither the general upward mobility of black workers commensurate with higher income nor the simultaneous increase in unemployment held any sway in abating the strike waves in this period. The class struggle further intensified towards the end of the depressive long wave and culminated in the 1987 strike wave. This greater wave of proletarian disruption resembling a revolutionary wave occurred in the trough of the depressive economic long wave (figure 5). The intense class war between labour, capital and the state had reached its peak. While black workers had won a major round of struggle between the 1970s and 1980s against both capital and the state, it is the crushing defeat of the 1987 National Union of Mine Workers’ strike, an HTP that would alter the balance of power once more. According to the Chamber of Mines Economics Department (1994, 63), “[a]n evident underlying aim of the strike was to demonstrate wide worker support for an agenda ranging from sanctions to seizure of control of the national economy”. While the miners were brutally defeated, the overall context in the country was insurrectionary and the call for socialism had become commonplace within the labour movement (Baskin Citation1991, 214). The apartheid capitalist state understood that a new level in the political struggle against apartheid capitalism had been reached and consequently, in 1990 (in the trough of the long wave—) the bans on political opposition parties ended, making possible a negotiated settlement to end apartheid—a PTP (Cottle Citation2020, 135).

Fifth long wave (1990–2019?)

Despite the reform of 1990, strike waves continued until the dismantling of apartheid South Africa in 1994. At the same time, this transformation restored capitalist profitability and promoted a neo-liberal dispensation. Changes to the labour process that began in the 1980s were now legalised into a two-tier labour market that divided the workforce between standard and non-standard forms of employment (Theron, Godfrey, and Lewis Citation2005, 1). Combined with the internationalisation of South African capitalism in the next 15 years South Africa’s real growth in GDP averaged 4.3 per cent (SARB Citation2017).

After the general elections there was a decline in the trend of strike frequency. While sectors with established labour relations mechanisms negotiated relatively peacefully, major strikes occurred in the health, police and municipal services sectors as well as in the fishing and transport industries (Bendix Citation2010, 92), but by 1997, strikes peaked at 1324 strikes, the highest number of strikes in South African history. The labour context remained turbulent as is evidenced in the fact that while strikes plummeted after 1998, the number of strikers increased, with 323,093 strikers in 1998, 555,435 in 1999 and 1,142,428 strikers in 2000—another historical record. Except for 1997, the strike wave of 1997–2000 was cyclical, occurring on the upswing of the business cycle, and marked the entry of strikes by public-sector workers in health, the police and municipal services over wages (van der Velden and Visser Citation2006, 63). Consequently, these strike waves did not produce noticeable structural effects, but illuminated that strike waves do occur along the upswing of economic long waves in contrast to what long-wave theorists have argued. Considering widespread retrenchments strikes became defensive between 2000 and 2004 with COSATU organising a general strike against job losses and government privatisation plans. However, over this period there was a decline in strike frequency, days lost and participation rates, which according to the Department of Labour was a period of “industrial restructuring” (Department of Labour Citation2003, 3), six years before the peak of the economic long wave.

Once again and in a predictable fashion the long wave of strikes intensifies around the peak of the economic long wave in 2005 (). This strike wave took place on a general upswing of the business cycle. Days lost in 2005 was 141 per cent higher than the mean of the preceding five years. An ITP in the level of class struggle occurred in 2005 where the trade union movement led by COSATU under pressure from its rank-and-file members began to adopt a more radical position. The 2005 strike wave was offensive in character, with trade unions fighting against the generalised effects of the industrial restructuring. Overall, the year 2005 is marked by the entry of precarious workers, wildcat strikes, attempts to unify standard and non-standard workers, an increase in the associational power of trade unions, widespread strike action across industries and general increases in persistence levels of workers. The turning point strike wave of 2005 came amidst favourable macroeconomic conditions and allowed for the resumption of strike action on a large scale. The structural effects of the ITP strike wave of 2005 signalled a revival of militant trade unionism and the beginning of the challenge to the neoliberal growth model. The strikes were reminiscent of some of the most violent strikes of the 1980s and fundamentally a contest over the changing nature of work (Department of Labour Citation2010, 4). The wave year of 2007 was illuminated by 608,919 strikers and 9.5 million days lost. The main causes of the strikes were wage-related, followed by disputes over conditions of work. Finally, the groundswell of militancy of the 2005–2007 turning point strike wave culminated in COSATU using its associational power to oust President Thabo Mbeki, who was viewed as the architect of neo-liberalism—a political structural effect. On a wave of confidence days lost doubled to about 1.2 million strikers and 20.6 million days lost in 2010. These strikes took place in a volatile political climate with COSATU asserting its position on the political demand to end labour broking.

The intensification of the class struggle along the depressive long wave culminated in the 2012 Marikana Massacre, where a peaceful assembly of platinum mine workers was forcefully broken up by a special paramilitary task team killing 34 miners—an HTP. The Marikana turning point strike triggered a wave of wildcat strikes in mining, the auto industry, among truck drivers and farmworkers (Alexander Citation2013, 609). This was shortly followed by the Western Cape Farm Workers’ and Community Uprising, which was unprecedented and spread to 25 rural towns and was led mostly by casual and seasonal workers including the unemployed, youth and poor people living in rural areas (Wilderman Citation2015, 4). These offensive strikes took place on the upswing of the business cycle. Once more, both the miners and farm workers had long-standing grievances related to wages and conditions of work. The Marikana HTP affected several structural dimensions. Economically, employment relations in the labour process were severely challenged combined with enormous costs to the economy. Further, the Labour Relations Amendment Act (No. 6 of 2014) now ensured that workers received protection, especially employees employed through a temporary employment service and fixed-term employees (Patel Citation2014). The Marikana strike wave further forced the South African government into dialogue with the labour movement around a national minimum wage (Department of Labour Citation2012). The political ruptures led a new opposition to the ANC, the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) and an alternative federation, which was independent of the ANC the South African Federation of Trade Unions (SAFTU), was formed by 52 trade unions. Marikana further reverberated throughout the country, triggering student protests who led the “Rhodes Must Fall” the “Fees Must Fall” campaigns and subsequently an alliance of students, workers and academics united around the “Outsourcing Must Fall” movement.

After two years the platinum miners consolidated themselves into the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (AMCU) and embarked on what became the historic five-month platinum strikes. While the strikes dragged the economy into contraction in the first quarter of 2014 the effect of the ruptures remained localised and did not trigger a wider response by workers (Fin24, June 24, 2014). While the number of strikes remained on the increase until 2019 there had since been a significant decline in the number of workers participating strikes with most strikes being of shorter duration, indicating that levels of exhaustion have set in, marking a retreat in the level of class struggle. Despite an increase in determination by workers in the private sector in 2022 making up 88 per cent of the 3.3 million days lost, these strikes have not registered any notable structural effects.

The eventual effect of the combined impacts of the Marikana turning point strike gave way to a political turning point in which the ANC-led government would initiate new reforms and economic policies in 2018 in order to restore the rate of profit. While introducing a national minimum wage the failure to mount an effective struggle by the labour movement had at the same time given way to draconian changes in strike law, which delay and inhibit the rights of workers to embark on protected strike action (Cottle Citation2018). Furthermore, the African National Congress has placed a stronger emphasis on austerity and the selling off major control over state parastatals (Businesstech, February 12, Citation2019; Dludla, June 11, Citation2021) as changes in its economic policies, representing a PTP. These changes in policy would provide new avenues for capital accumulation and the resumption of capital accumulation in the next expansive economic long wave.

Conclusion

The application of long-wave theory and the application of a new quantitative technique in this article has revealed that that there is a predicable patterning to significant periods of labour mobilisation. This study, however, contradicts Mandel’s depiction of the class struggle curve as having a convex curve mirroring the long wave of economic development. Rather, the patterning of long waves of strikes displays a concave movement (countercyclical) to economic long waves. This is an important finding and proves the relative autonomy of the class struggle from economic long waves. In this way the initial turning point (ITP) in the general movement of intensification of the class struggle occurs around the peak of capitalist long waves, intensifies towards the trough of the depressive long wave, culminating in a historical turning point (HTP), which ushers in political reforms, revolution or defeat; giving way to a political turning point (PTP), which leads to changes in political representation and changes in economic and social policy. Thus, overall, the general movement of intensification moves in an opposite direction to economic long waves refuting the “race-to-the-bottom thesis” (Silver Citation2003, 5) that neo-liberalism created the conditions for a generalised downward spiral in workers resistance. A key concern in approaches in the study of the rise and decline of strikes across the globe is that the lack of interest in long-wave theory has greatly disarmed the left in foreseeing and preparing for the working-class upsurges at the beginning of the twenty-first century.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dr Marcellin Atemkeng, a specialist in big data and statistical signal processing from Rhodes University, and Serge Hadisi, senior analyst at Political Economy Southern Africa, for their assistance with the cross-spectral analysis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 The term turning point is interchangeably used with what historians call historic events – “that in some sense ‘change the course of history’” (Sewell Citation2005, 842).

2 This study was unable to conduct a spectral analysis from 1886 as the international standardisation of GDP data was introduced in South Africa in 1946 creating a break in the GDP series for prior years.

3 Patnaik, P. 2019. “The global shift to the right”. Monthly Review Online. 4 June. https://mronline.org/2019/06/04/the-global-shift-to-the-right/ [accessed 1 July 2019].

4 Own calculations based on Alexander (Citation2000), table 1.4: Profile of 209,318 workers, covered by wage determinations, 1937–1946.

References

- Alexander, Peter. 2000. Workers, War and the Origins of Apartheid: Labour & Politics in South Africa 1939–48. Cape Town: David Philip.

- Alexander, P. 2013. “Marikana, Turning Point in South African History.” Review of African Political Economy 40 (138): 605–619.

- Backer, W., and G. Oberholzer. 1995. “Strike and Political Activity: A Strike Analysis of South Africa for the Period 1910–1994.” South African Journal of Labour Relations 19 (3): 3–32.

- Baskin, J. 1991. Striking Back: A History of Cosatu. Johannesburg: Ravan Press.

- Beittel, M. 1995. “Labor Unrest in South Africa, 1870–1990.” Review (Fernand Braudel Center) 18 (1): 87–104.

- Bell, Jocelyn A. 2001. “The Influence on the South African Economy of the Gold Mining Industry 1925–2000.” South African Journal of Economic History 16 (1–2): 29–46. doi:10.1080/10113430109511132.

- Bendix, S. 2010. Industrial Relations in South Africa. Cape Town. Juta and Co.

- Berger, I. 1992. Threads of Solidarity: Women in South African Industry, 1900-1980. Indiana: Indiana University Press.

- Bonner, Phil. 1987. “Overview: Strikes and the Independent Trade Unions.” In The Independent Trade Unions, edited by Johann Maree, 55–61. Johannesburg: Ravan Press.

- Bonnin, Debby. 1987. Class, Consciousness and Conflict in the Natal Midlands, 1940–1987: The Case of the B.T.R. Sarmcol Workers. Durban: University of Natal.

- Bordogna, L. and G Provasi. 1979. “Il movimento degli scioperi in Italia (1881–1973).” In Il movimento degli scioperi nel XX secolo, 169–304. Bologna: Il Mulino.

- Businesstech. 2019. “South Africa is About to Enter Several Years of Austerity: Economists”. February 12. Accessed March 22, 2023. https://businesstech.co.za/news/finance/467824/south-africa-is-about-to-enter-several-years-of-austerity-economists/.

- Casutt, Julia. 2012. “The Influence of Business Cycles on Strike Activity in Austria, Germany and Switzerland.” In Striking Numbers: New Approaches to Quantitative Strike Research, edited by van der Velden, Sjaak, 13–58. Amsterdam: International Institute of Social Research.

- Cottle, E. 2017. “Long Waves of Strikes in South Africa: 1900–2015.” In Where Have all Classes Gone? Collective Action and Social Struggles in a Global Context. Vol. 8, edited by O. Balashova, I. Karatepe, and A. Namukasa, 146–171. Munich: Rainer Hampp Verlag.

- Cottle, E. 2018. “The Labour Relations Amendment Bill – A Victory for Business”. Daily Maverick, June 4. Accessed October 7, 2023. https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/opinionista/2018-06-04-the-labour-relations-amendment-bill-a-victory-for-business/.

- Cottle, E. 2020. Long Waves of Strikes in South Africa: 1886-2019. Doctoral Thesis. Makanda: Rhodes University.

- Cottle, E. 2022. “Lenin and Trotsky on the Quantitative Aspects of Strike Dynamics and Revolution.” Workers of the World 1 (10).

- Cottle, E. 2023. “Industrial Action in South Africa (2000–2020): Reading Strike Statistics Qualitatively.” Global Labour Journal 14 (2), doi:10.15173/glj.v14i2.5111.

- Cronin, J. E. 1980. “Stages, Cycles and Insurgencies: The Economics of Unrest.” Processes of the World System 3: 101–118.

- Davies, Robert H. 1979. Capital, State and White Labour in South Africa: 1900–1960; An Historical Materialist Analysis of Class Formation and Class Relations. Brighton, Sussex: Harvester Press.

- Department of Labour. Industrial Action Report (2003). Pretoria: Department of Labour.

- Department of Labour. Industrial Action Report (2010). Pretoria: Department of Labour.

- Department of Labour. Industrial Action Report (2012). Pretoria: Department of Labour.

- Dludla, N. 2021. “South African Government Sells Majority Stake in Airline SAA to Consortium”. Reuters, June 11. Accessed March 22, 2023. https://www.reuters.com/business/aerospace-defense/consortium-take-51-stake-south-african-airways-minister-2021-06-11/.

- Dockès, Pierre and Rosier, B. 1992. “Long Waves and the Dialectic of Innovations and Conflicts.” In New Findings in Long-Wave Research, edited by Kleinknecht, E., Mandel, E and Wallerstein, I. Bansingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 301-315.

- Feinstein, C. H. 2005. An Economic History of South Africa: Conquest, Discrimination, and Development. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Franzosi, R. 1995. The Puzzle of Strikes: Class and State Strategies in Postwar Italy. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Friedman, S. 1987. Building Tomorrow Today; African Workers in Trade Unions 1970–84. Johannesburg: Ravan Press.

- Gallas, A., and J. Nowak. 2016. “Introduction: Mass Strikes in the Global Crisis.” Workers of the World 1 (8): 7–16.

- Gattei, G. 1989. “Every Twenty-Five Years: Strike Waves and Long Economic Cycles.” Paper Presented at the Long Wave Conference, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, the Universiteit van Amsterdam, the Fernand Braudel Center and the Maison des Sciences de I’Homme, Brussels, January12–14.

- Gelb, Stephen, ed. 1991. South Africa's Economic Crisis.. Cape Town, NJ: D. Philip; Zed Books.

- Harris, K. 1991. “The 1907 Strike: A Watershed in South African White Miner Trade Unionism.” African Historical Review 23 (1): 32–51.

- Hirson, B. 1979. Year of Fire, Year of Ash: The Soweto Revolt: Roots of a Revolution? London: Published by Zed Press.

- Hobsbawm, E. J. 2015. Labouring Men: Studies in the History of Labour. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

- Horrell, M., D. Horner, and J. Kane-Berman. 1965. A Survey of Race Relations in South Africa 1966. Johannesburg: South Africa Institute of Race Relations.

- Houghton, H. D. 1969. The South African Economy. Cape Town: Oxford University Press.

- Howe, G. 1984. “Strike Trend Indicators 1982–1984: A Comparative Review of Official and Independent Monitors.” Indicator South Africa 2 (2): 3–9.

- Jackson, D., & Sweet, T. 1979. "The world strike wave". Omega: The International Journal of Management Science 7(1): 43-53.

- Johnstone, A. 1976. Class, Race, and Gold: A Study of Class Relations and Racial Discrimination in South Africa (Vol. 6). Lanham, Maryland: University Press of America

- Katzen, Leo. 1964. Gold and the South African Economy: The Influence of the Goldmining Industry on Business Cycles and Economic Growth in South Africa, 1886-1961. Cape Town: Balkema.

- Kelly, J. 1997. “Long Waves in Industrial Relations: Mobilization and Counter-Mobilization in Historical Perspective.” Historical Studies in Industrial Relations 4: 3–35. doi:10.3828/hsir.1997.4.2.

- Kelly, J. 1999. Rethinking Industrial Relations: Mobilisation, Collectivism and Long Waves. London, NY: Routledge.

- Koenker, D. P., and W. G. Rosenberg. 1989. “Strikes and Revolution in Russia, 1917.” In Strikes, Wars, and Revolutions in an International Perspective: Strike Waves in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries, edited by Leopold H. Haimson, and Charles Tilly, 167–196. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Levy, A. 1985. “The Limitations of South African Strike Statistics.” Indicator South Africa 3 (2): 9–12.

- Mandel, E. 1980. Late Capitalism, 2nd ed. London: Verso.

- Mandel, E. 1995. Long Waves of Capitalist Development: A Marxist Interpretation: Based on the Marshall Lectures Given at the University of Cambridge. 2nd rev. ed. London, NY: Verso.

- Maree, Johann, ed. 1987. The Independent Trade Unions, 1974–1984: Ten Years of the South African Labour Bulletin. Vol. 2. Johannesburg: Ravan Press.

- Marxist Workers Tendency. 1984. “Lessons of the 1950s.” Inqaba Ya Basebenzi - Journal of the Marxist Workers Tendency of the ANC 13, March/May 1984. https://marxistworkersparty.org.za/?page_id=324

- Metz, R. 1992. “A Re-Examination of Long Waves in Aggregate Production Series.” In New Findings in Long-Wave Research, edited by A. Kleinknecht, E. Mandel, and I. Wallerstein, 80–119. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Metz, R. 1992. “A Re-examination of Long Waves in Aggregate Production Series. In New findings in long-wave research, edited by Kleinknecht, A., Mandel, E and Wallerstein, I. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 80-113.

- Moodie, T. D. 1986. “The Moral Economy of the Black Miners’ Strike of 1946.” Journal of Southern African Studies 13 (1): 1–35.

- O’Meara, D. 1975. “The 1946 African Mine Workers’ Strike and the Political Economy of South Africa.” Journal of Commonwealth & Comparative Politics 13 (2): 146–173. doi:10.1080/14662047508447235.

- Padayachee, V., Shahid, V., and Tichmann, P. 1985. “Indian Workers and Trades Unions in Durban: 1930–1950.” Institute for Social Research, University of Durban-Westville.

- Patel, A. 2014. “The Labour Relations Amendment Act Will Take Effect on 1 January 2015.”https://www.cliffedekkerhofmeyr.com/en/news/publications/2014/employment/employment-alert-11-december-the-labour-relations-amendment-act-will-take-effect-on-1-january-2015.html.

- Rand Daily Mail (Johannesburg, South Africa). 1964. “Distorted Claims by Textile workers’. February 1, 1964: 1.

- Rand Daily Mail (Johannesburg, South Africa). 1971. “23 000 Claim Victory in pay Dispute.” February 25, 1971: 3.

- Scerri, Mario. 2016. The Emergence of Systems of Innovation in South(ern) Africa: Long Histories and Contemporary Debates. Johannesburg: Real African Publishers.

- Screpanti, E. 1984. “Long Economic Cycles and Recurring Proletarian Insurgencies.” Review (Fernand Braudel Center) 7 (3): 509–548.

- Screpanti, E. 1987. “Long Cycles in Strike Activity: An Empirical Investigation.” British Journal of Industrial Relations 25 (1): 99–124. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8543.1987.tb00703.x.

- Sewell Jr, William H. 2005. Logics of History: Social Theory and Social Transformation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Shaikh, A. 2016. Capitalism: Competition, Conflict, Crises. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Shane, S., and J. Farnham. 1985. Strikes in South Africa, 1960–1984. Report PERS 388. Pretoria: Human Sciences Research Council.

- Shear, K. 1994. The 1907 Strike: A Reassessment. Johannesburg: Institute for Advanced Social Research, University of the Witwatersrand.

- Shorter, E. and Tilly, C. (1974). Strikes in France 1830–1968. London: Cambridge University Press.

- Silver, B. J. 1992. “Class Struggle and Kondratieff Waves, 1870 to the Present.” In New Findings in Long-Wave Research, edited by A. Kleinknecht, E. Mandel, and I. Wallerstein, 279–300. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Silver, B. J. 1995. “World-Scale Patterns of Labor-Capital Conflict: Labor Unrest, Long Waves, and Cycles of World Hegemony.” Review (Fernand Braudel Center) 18 (1): 155–192.

- Silver, B. J. 2003. Forces of Labor: Workers’ Movements and Globalization Since 1870. Cambridge, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- South African, Reserve Bank. 2010. Annual Economic Report, 2017. Pretoria: South African Reserve Bank.

- Theron, Jan, Shane Godfrey, and Peter Lewis. 2005. The Rise of Labour Broking and Its Policy Implications. Labour Enterprise Project. Cape Town: University of Cape Town.

- Trotsky, L. 1921. Report on the World Economic Crisis and the New Tasks of the Communist International. Marxist Archive. https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1924/ffyci-1/ch19.htm.

- Trotsky, L. 1941. “The Curve of Capitalist Development.” New York, Fourth International, Vol.2. (4), 111–114.

- van der Velden, S., and W. P. Visser. 2006. “Strikes in the Netherlands and South Africa, 1900–1998: A Comparison.” South African Journal of Labour Relations 30 (1): 51–75.

- Wallerstein, I. 1992. “A Brief Agenda for the Future of Long-Wave Research.” In New Findings in Long-Wave Research, edited by A. Kleinknecht, A Ernest Mandel, and I. Wallerstein, 339–342. New York: Martin’s Press.

- Wilderman, J. 2015. “From Flexible Work to Mass Uprising: The Western Cape Farm Workers’ Struggle.” Society, Work and Development Institute. Working, paper 4.

- Wilkinson, P. 1981. “A Place to Live: The Resolution of the African Housing Crisis in Johannesburg, 1944–1954.” African Studies Seminar Paper. Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersrand.

- Williams, M. S. 2017. Examining the Economic Impact of Industrial Action Activities in South Africa, 2003-2014. Master of Economics. Department of Economics. University of the Western Cape.

- Wilson, Francis. 1972. Labour in the South African Gold Mines: 1911–1969. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Yudelman, David. 1984. The Emergence of Modern South Africa: State, Capital, and the Incorporation of Organized Labor on the South African Gold Fields, 1902–1939. Cape Town: New Africa Books.