ABSTRACT

Objectives

Sepsis is a common cause of maternal mortality and morbidity. Early detection and rapid management are essential. In this study, we evaluate the compliance with the implemented maternity-specific Early Warning Score (EWS), Rapid Response Team (RRT) protocol and the Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC) Hour-1 Bundle in a tertiary hospital in the Netherlands.

Methods

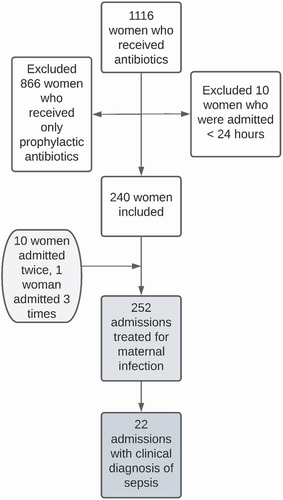

We performed a retrospective patient chart review from July 2019 to June 2020 at the Leiden University Medical Centre. We included women who received therapeutic antibiotics and were admitted for at least 24 hours.

Results

We included 240 women: ten were admitted twice and one woman three times, comprising 252 admissions. A clinical diagnosis of sepsis was made in 22 women. The EWS was used in 29% (n = 73/252) of admissions. Recommendations on the follow-up of the EWS were carried out in 53% (n = 46/87). Compliance with the RRT protocol was highest for assessment by a medical doctor within 30 minutes (n = 98/117, 84%) and lowest for RRT involvement (n = 7/23, 30%). In women with sepsis, compliance with the SSC Bundle was highest for acquiring blood cultures (n = 19/22, 85%), while only 64% (n = 14/22) received antibiotics within 60 minutes of the sepsis diagnosis.

Conclusion

The adherence to the maternity-specific EWS and the SSC Hour-1 bundle was insufficient, even within this tertiary setting in a high-income country.

Introduction

Maternal sepsis is increasingly recognized as an important, yet underreported cause of maternal morbidity and mortality worldwide [Citation1]. The Global Maternal and Neonatal Sepsis Initiative defines maternal sepsis as ‘a life-threatening condition defined as organ dysfunction resulting from infection during pregnancy, childbirth, post-abortion, or post-partum period.’ It is considered a clinical diagnosis made at the bedside, based on signs and symptoms [Citation2,Citation3].

Early detection and early management are key in preventing complications and mortality from maternal sepsis [Citation4–6]. Pregnancy-specific measures are necessary to detect maternal sepsis, since maternal physiology is altered during and shortly after pregnancy. Several maternity-specific Early Warning Scores (EWS) for early detection have been developed. These are based on clinical parameters such as temperature, systolic blood pressure, pulse and respiratory rate adapted to the pregnant state, which require adapting cutoff parameters for clinical derangement [Citation7,Citation8]. High EWS values should trigger hospital-specific escalation protocols, which specify preventative or therapeutic actions [Citation8,Citation9].

Secondly, the Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC) Hour-1 Bundle specifies recommendations for the early management of sepsis, that should be initiated within one hour of sepsis detected [Citation10]. While the SSC guidelines are criticized by some for being based on evidence of moderate to low quality, multiple studies have shown marked improvements in mortality and other clinical outcomes following implementation [Citation11,Citation12].

Two recent studies in middle-income countries reported moderate compliance with the Hour-1 Bundle in obstetric departments [Citation6,Citation13]. The authors described that sepsis detection was poor due to a lack of maternity-specific EWS implementation, delaying prompt action required to prevent maternal deaths or near-misses. Although several studies report the use of EWS, none provide in-depth information on the compliance to their escalation protocols [Citation14–16]. This lack of information pertaining to compliance is present in high-income settings as well as low- and middle-income settings. In high-income settings, adherence is expected to be higher due to larger numbers of available human and material resources, in combination with a lower burden of sepsis patients.

We investigated compliance with maternal sepsis detection and management protocols in women who were managed for maternal infection in a tertiary teaching hospital in the Netherlands. We assessed the application of maternity-specific EWS, the compliance with the Rapid Response Team (RRT) escalation protocol, and we evaluated adherence to the SSC Hour-1 Bundle in women with a clinical diagnosis of sepsis.

Materials and methods

Study design

We conducted a patient chart review over a period of one year, from July 2019 to June 2020.

Participants

We obtained a list of all women who were pregnant or within 6 weeks postpartum and received antibiotics during the study period through the hospital pharmacy. We retrieved the electronic medical records of these women and screened them for inclusion. We included women if they received therapeutic antibiotics and were admitted to the maternity ward for at least 24 hours. If women were admitted more than once and fulfilled the inclusion criteria, each admission was reviewed separately. All data were collected from the electronic patient records and entered into IBM SPSS Statistics 24 by the first author during a period of eight weeks [Citation17]. Women were considered to have been diagnosed with sepsis if the term ‘sepsis’ was discovered anywhere in any of the clinical notes, including surgical notes and culture requests during the admission period. This includes, for instance, documentation of a specific type of infection ‘with clinical signs of sepsis.’

Setting

We conducted the study at the Leiden University Medical Centre (LUMC), a highly specialized tertiary teaching hospital in the Netherlands and a referral center for six secondary hospitals in the region. The maternity clinic is located within the Department of Obstetrics and Neonatology. Care is provided by midwives, either independently (primary care midwives), or by midwives and doctors under the supervision of one of fourteen consultant obstetrician-gynecologists. During the study period, 2880 women gave birth in the hospital, of whom 412 received primary birth care (14.3%) and 2468 (85.7%) secondary or tertiary care under the supervision of an obstetrician-gynecologist. On 2437 women (84.6%), additional information was available to provide context for our study setting, see Appendix 1. All relevant measures are in place to prevent complications of maternal infection, including a maternity-specific EWS and clinical guidance compliant with the SSC Hour-1 Bundle of Care.

Interventions

The Obstetric Early Warning Score (OEWS) as used in the hospital consists of several clinical parameters. Measurement of the OEWS occurs at the discretion of the nurse or if recommended by an obstetrician (or a registrar in training). An OEWS score of 3 or more triggers a hospital-specific RRT escalation protocol (Appendix 2). The SSC Hour-1 Bundle consists of five actions that should be initiated (but not necessarily completed) within one hour of detection of sepsis: measurement of lactate, blood culture collection, and administration of antibiotics, intravenous fluid and vasopressors (Appendix 3).

Variables

We assessed implementation of the OEWS based on three criteria: (1) application, (2) compliance with recommendations for frequency of OEWS assessment and (3) compliance with the associated RRT protocol. We assessed compliance with the SSC Hour-1 Bundle separately for each of its recommendations (Appendix 3).

Analysis

We used descriptive statistics and reported data in numbers and percentages using IBM SPSS Statistics 24 [Citation17]. The graphs were made using Lucidchart software version March 2023 [Citation18]. Missing data are indicated in text, tables and figures as ‘unknown’ and clarified in the legends of tables or figures.

Ethical approval

The Medical Ethical Review Committee of the hospital confirmed that ethical approval was not required since the Medical Research involving Human Subjects Act did not apply to this study (reference number 22–3049). Women were excluded from analysis if they did not provide consent for the use of their data for medical research, as annotated accordingly in their medical files (n = 0). Given that the retrospective data were anonymized after extraction, no additional informed consent was required.

Results

We included 240 women, of whom ten were admitted twice and one was admitted three times. This yielded a total of 252 admissions. In 22 of these admissions, a clinical diagnosis of sepsis was reported in the medical records. depicts the process of participant inclusion.

demonstrates the characteristics of the study population, the adverse events and the underlying causes of infection in women with a suspected sepsis and a clinical diagnosis of sepsis as per our case definition.

Table 1. Characteristics, adverse events and underlying cause of infection of women with a suspected sepsis and a clinical diagnosis of sepsis.

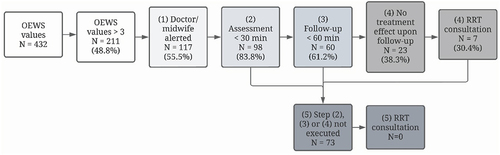

The OEWS was applied in 29% (n = 73/252) of admissions. Appendix 4 shows adverse events in women who did and did not receive OEWS monitoring. In 16% (n = 39/252) of admissions, one or more recommendations were found in the medical records for the frequency of OEWS measurement. In total, 87 recommendations were made, of which 53% (n = 46/87) were complied with. In 73 women, 432 OEWS values were recorded, of which 211 (48.8%) were 3 or higher, which is the threshold for action according to the RRT protocol.

depicts compliance with the RRT protocol. Compliance was highest for the assessment of a woman with a high OEWS score, where in 83% of cases (n = 98/117) a clinician assessed the woman within 30 minutes. The lowest compliance was seen with regard to the steps requiring RRT consultation, for example, when no treatment effect was seen upon follow-up, the RRT was consulted in only 30% of cases (n = 7/23).

Figure 2. Compliance with RRT protocol.

describes compliance with the SSC Hour-1 Bundle of Care within one hour, which was high for taking blood cultures (86%, n = 19/22), moderate for the administration of antibiotics (64%, n = 14/22) and fluids (46%, n = 10/18) and poor for the assessment of the lactate level (5%, n = 1/22).

Table 2. Compliance with the SSC hour-1 bundle.

Three women (1%) were admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) for a deteriorating condition due to an infection. One woman developed fever during childbirth and gave birth by cesarean, and was admitted to the ICU due to clinical deterioration. Two women developed sepsis following vaginal birth. Although the OEWS was measured in all three women, found to be high in all three (range 4–16) and clinicians assessed these women within 30 minutes, the RRT was not consulted in any of them. The adherence to the SSC bundle was incomplete, as blood cultures were taken and antibiotics were administered within 60 minutes, while lactate measurements were performed in 80–1397 minutes. Fluid resuscitation occurred in all three cases. The time to fluid resuscitation was not recorded.

Discussion

This study sought to investigate compliance with a maternity-specific EWS and the SSC Hour-1 Bundle in women managed for a maternal infection. As our study shows, although recommended in clinical guidance, the application of a maternity-specific EWS was not systematically practiced in this setting. Providing a recommendation for the frequency of measurement was not performed sufficiently frequent and compliance with this recommendation varied substantially. Moreover, an elevated EWS was not always acted upon. Implementation is expected to be even poorer in settings with more limited resources and a higher burden of infection.

We believe that the strength of our study lies in the in-depth assessment of the quality of care for maternal sepsis. To our knowledge, no other similar studies exist in high-income settings. Despite the retrospective nature of our study, we were able to retrieve precise timing of conducted OEWS and SSC Hour-1 bundle actions due to the automatically generated timestamps in the digital medical files. We acknowledge that important limitations include potential selection bias, as women were retrospectively included if they had received antibiotic treatment, and we acknowledge that the number of women with sepsis included in our study is relatively low. In the selection of cases fulfilling our definition of sepsis, incomplete or incorrect medical charts may have led to underreporting of women who were in practice treated as sepsis patients. It is also possible that cases of sepsis were missed by the managing clinician. Underreporting of milder, self-limiting cases is most likely to have occurred, implying perhaps even poorer adherence to the protocols than reported in this study. Finally, 35% of admissions occurred during the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic, during which there might have been increased attention to EWS and sepsis protocols.

Several barriers to maternity-specific EWS implementation have been identified in qualitative studies, which might explain the limited implementation we found, including, but not limited to, suspected impact on the woman in labor due to frequent interruptions, increased workload and perceived limited benefit from the application of the EWS [Citation19,Citation20]. In other words, the low threshold for actions required in only mildly elevated EWS may not always be feasible or found to be clinically relevant in our setting, let alone in low-resource, high-burden settings. Raising the threshold of action to moderate to serious elevations of EWS, such as in the 3 ICU admissions in this study, might lead to earlier RRT intervention. There is, however, no conclusive evidence that RRT intervention decreases the incidence of ICU admissions [Citation21]. The differences in the occurrence of adverse events between women who did and did not receive EWS monitoring found in our study can possibly be explained by the fact that severe cases may have been more likely to receive monitoring.

Similar to the results of EWS implementation, compliance with the SSC Hour-1 Bundle was moderate. The lack of compliance to these guidelines in a high-resource setting may be the consequence of limited risk perception of clinicians, as only few women suffer severe consequences of maternal sepsis. Yet, the incidence of sepsis (8 per 1000 births) and ICU admission due to sepsis (1 per 1000 births) in our study is rather high compared to previous studies from other high-income settings [Citation22–25]. This may reflect the patient population in this referral hospital. On the other hand, these findings warrant improved sepsis detection and management, especially considering the increase in risk factors for infections, such as obesity, older maternal age and increasing cesarean section rates.

We recommend studying whether lower compliance rates to sepsis detection and management measures are associated with increased severity of sepsis and increased incidence of complications, and how we may overcome barriers to compliance with clinical guidance.

Conclusion

Adherence to the maternity-specific EWS and SSC Hour-1 Bundle was insufficient in our high-income referral hospital. This could be due to a lack of feasibility of the protocols as well as low risk perception among doctors, midwives and nurses. The applicability and feasibility of these guidelines could be improved by performing maternal sepsis audits, developing a visually-attractive digital toolkit to aid compliance and by raising the threshold of action to moderately elevated EWS depending on the clinical setting.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

Baukje S. de Vries performed data acquisition, primary data analysis and drafted the first and the final version of the manuscript. Kim J. C. Verschueren contributed to analysis and interpretation, and reviewed the initial draft. Sophie Jansen and Vincent Bekker contributed to study design and substantially contributed to the final manuscript. Marieke B. Veenhof co-supervised the project and reviewed the first and final drafts. Thomas van den Akker conceived the study, supervised the project and data interpretation and reviewed all drafts of the manuscript, including the final draft.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (31.6 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the hospital pharmacy for providing us the list of our study participants.

Data availability statement

Data and materials supporting the results presented in this paper are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/21548331.2024.2320068

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bonet M, Brizuela V, Abalos E. Frequency and management of maternal infection in health facilities in 52 countries (GLOSS): a 1-week inception cohort study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020 May;8(5):e661–e671. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30109-1

- The global maternal and neonatal sepsis initiative: a call for collaboration and action by 2030. Lancet Glob Health. 2017 Apr;5(4):e390–e391. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30020-7

- WHO.int. Statement on maternal sepsis [internet]. 2017 [cited 2022 Jun 23]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-RHR-17.02

- Levy MM, Rhodes A, Phillips GS, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: association between performance metrics and outcomes in a 7.5-year study. Crit Care Med. 2015 Jan;43(1):3–12.

- Ford JM, Scholefield H. Sepsis in obstetrics: cause, prevention, and treatment. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2014 Jun;27(3):253–8. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0000000000000082

- Kodan LR, Verschueren KJC, Kanhai HHH, et al. The golden hour of sepsis: an in-depth analysis of sepsis-related maternal mortality in middle-income country Suriname. PloS One. 2018;13(7):e0200281. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0200281

- Isaacs RA, Wee MY, Bick DE, et al. A national survey of obstetric early warning systems in the United Kingdom: five years on. Anaesthesia. 2014 Jul;69(7):687–92.

- Umar A, Ameh CA, Muriithi F, et al. Early warning systems in obstetrics: a systematic literature review. PloS One. 2019;14(5):e0217864. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0217864

- Carle C, Alexander P, Columb M, et al. Design and internal validation of an obstetric early warning score: secondary analysis of the intensive care national audit and research centre case mix programme database. Anaesthesia. 2013 Apr;68(4):354–67.

- Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016. Intensive care Med. 2017 Mar;43(3):304–377.

- Rello J, Tejada S, Xu E, et al. Quality of evidence supporting surviving sepsis campaign recommendations. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2020 Aug;39(4):497–502.

- Mukherjee V, Evans L. Implementation of the surviving sepsis campaign guidelines. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2017 Oct;23(5):412–416. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000438

- Yousuf F, Malik A, Saba A, et al. Risk factors and compliance of surviving sepsis campaign: a retrospective cohort study at tertiary care hospital. Pak J Med Sci. 2022 Jan;38(1):90–94.

- Tuyishime E, Ingabire H, Mvukiyehe JP, et al. Implementing the risk identification (RI) and modified early obstetric warning signs (MEOWS) tool in district hospitals in Rwanda: a cross-sectional study. Bmc Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020 Sep 29;20(1):568. doi: 10.1186/s12884-020-03187-1

- Gillespie KH, Chibuk A, Doering J, et al. Maternity nurses’ responses to maternal early warning criteria. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2021 Jan;46(1):36–42.

- Maguire PJ, Power KA, Daly N, et al. High dependency unit admissions during the first year of a national obstetric early warning system. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2016 Apr;133(1):121–2.

- Corp IBM. IBM SPSS statistics for windows, version 24. Armonk NY: IBM Corp; 2016.

- Lucidchart. Lucidchart software version. Lucid Software Inc; 2023.

- Carlstein C, Helland E, Wildgaard K. Obstetric early warning score in Scandinavia. A survey of midwives’ use of systematic monitoring in parturients. Midwifery. 2018 Jan;56:17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2017.09.015

- Bick DE, Sandall J, Furuta M, et al. A national cross sectional survey of heads of midwifery services of uptake, benefits and barriers to use of obstetric early warning systems (EWS) by midwives. Midwifery. 2014 Nov;30(11):1140–6.

- Ludikhuize J, Brunsveld-Reinders AH, Dijkgraaf MG, et al. Outcomes associated with the nationwide introduction of rapid response systems in the Netherlands. Crit Care Med. 2015 Dec;43(12):2544–2551.

- van Dillen J, Zwart J, Schutte J, et al. Maternal sepsis: epidemiology, etiology and outcome. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2010 Jun;23(3):249–254.

- Acosta CD, Knight M, Lee HC, et al. The continuum of maternal sepsis severity: incidence and risk factors in a population-based cohort study. PloS One. 2013;8(7):e67175. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067175

- Acosta CD, Harrison DA, Rowan K, et al. Maternal morbidity and mortality from severe sepsis: a national cohort study. BMJ Open. 2016 Aug 23;6(8):e012323. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012323

- World Health Organization. Global report on the epidemiology and burden of sepsis: current evidence, identifying gaps and future directions. Wor Heal Org. 2020.