ABSTRACT

Science museums are beginning to see themselves as important players in a number of scientific, social, cultural and political contexts. They are embracing broader societal issues, especially in a time of population and environmental stress. In this paper, we focus on museum staff perspectives about the exhibition Our World (Canada), that delves into issues of water, food and energy consumption, and waste. Specifically, we sought to explore expectations and tensions that framed the renovation of the exhibit and to interpret them through theory related to scientific literacy and exhibition typologies. Using case study, we relied primarily on semi-structured interviews with museum staff, and secondarily on observations, field notes, and documents. Our findings are organized around: the renovation of narratives and forms of representation, and the ways in which the visitor experience is reimagined. The (re)conceptualization of this gallery illustrates an attempt to move from a pedagogical to critical and agential emphases, through which progressive views of scientific literacy could be at play. Our discussion examines the role of information, the in-between positions that museum staffers experienced and pathways towards civic responsibility. Concluding thoughts centre around the concept of productive struggle, the role of knowledge and issues of neutrality.

Introduction

Complex issues positioned at the intersection of science, technology, society and environment are becoming part of the repertoire of educational and cultural actions enacted by these institutions (Cameron & Deslandes, Citation2011; Cameron et al., Citation2013; Pedretti & Navas Iannini, Citation2020). Museums are beginning to see themselves as important players in a number of scientific, social, cultural and political contexts. Exhibits about climate change (KlimaX – The Norwegian National Museum of Science, Technology, and Medicine), biodiversity loss (Schad Gallery: Life in Crises, Royal Ontario Museum) and food consumption (Comer: Las mesas de América Latina [Eating: Dining rooms in Latin America], Parque Explora) are but a few examples of museums’ evolving landscapes and changing exhibitionary practices.

For some, it is imperative that museums embrace broader societal issues, especially in a time of population, energy, environmental, climate and economic stress (Evans & Achiam, Citation2021; Janes, Citation2009; Janes & Sandell, Citation2019), and more recently, as we have witnessed, the pandemic. Transcending the idea of temples housing collections, science museums are increasingly called to become arenas for public debate (Cameron, Citation1971; Cameron et al., Citation2013; Henriksen & Frøyland, Citation2000), and venues where critical and civic scientific literacy can be fostered (Hine & Medvecky, Citation2015; Rennie & Williams, Citation2006) and citizens can be prepared for sustainable futures (Barrett & Sutter, Citation2006; Evans & Achiam, Citation2021). It also expected that these institutions could engage the ‘experiential, critical and political capabilities of the audience’ (Cameron, Citation2006, ‘Conclusion’, para. 3). Yet, embracing broader and more relevant science and environmental issues pose challenges to science museums, and their exhibitions, due to the myriad of contexts and tensions in which these contemporary topics are immersed. Additionally, advancing critical and civic scientific literacy in/through science museums (Henriksen & Frøyland, Citation2000; Hine & Medvecky, Citation2015) presents difficulties related to the ways in which public engagement can be fostered and encouraged. According to Rennie and Williams (Citation2006), civic forms of scientific literacy confront traditional images of science museums (as perceived by the audience) as places where impersonal, trustworthy information is displayed, to spaces where relevant and sensitive information co-exists with opinions, points of view, criticality and action.

In this paper, we explore museum staffs’ perspectives, aspirations and tensions that emerged from their work while renovating the exhibition Our World: BMO Sustainability Gallery (Science World, Vancouver; hereafter referred to as Our World). A Canadian exhibition, Our World focuses on sustainability and delves into issues of water, food and energy consumption, and waste. It should be noted that this case study is part of a larger funded research project focusing on critical science exhibition case studies from around the world (Pedretti & Navas Iannini, Citation2020). Although our larger research interests have included visitor responses and engagement (e.g. Navas Iannini & Pedretti, Citation2017; Pedretti & Navas Iannini, Citation2018), for the purposes of this paper we focus on staff perspectives. Specifically, our research goals were to:

(1) examine the goals and expectations that framed the conceptualization and (re)development of the exhibit Our World, and

(2) explore barriers or tensions that staff identified as part of these processes.

Using lenses provided by theory in the fields of scientific literacy and museum studies, we sought to interpret museum staffers’ views and perspectives about the exhibit. Our intent is to unravel some of the possibilities and complexities that emerge when science museums foster public engagement around difficult and contemporary environmental and societal issues.

Literature review

For the purposes of this work, we draw upon literature pertaining to scientific literacy, and typologies of science museum exhibitions. We argue these perspectives are useful in helping us make sense of institutional aspirations and tension (for the visit and the visitor experience) in the specific context of an exhibition about sustainability.

Scientific literacy is a theoretical construct that has been interpreted widely through different arrays of abilities, capacities, dimensions, understandings and processes (Hodson, Citation2003). Recently, progressive views of scientific literacy call for the development of skills that would help citizens navigate the complexities of scientific issues and their social implications, engage in informed decision-making and enact change. In tandem with these ideas, we note that education for sustainable development – alongside its contemporary purposes, competences and abilities (see, for example, Reickmann Citation2018) – aligns with progressive views of scientific literacy and the pursuit of social and environmental change. Similarly, typologies of science museum exhibitions (Pedretti, Citation2002; Pedretti & Navas Iannini, Citation2020; Wellington, Citation1998) have been interpreted widely, and include a range of displays that historically have focussed on pedagogical and experiential goals to more contemporary purposes encompassing criticality and agency. With these considerations in mind, we begin our review by unpacking scientific literacy.

Unpacking scientific literacy

Despite the importance and spread of scientific literacy, its meanings and interpretations are blurred and, under constant construction and reconsideration. Earlier works in the field of scientific literacy can help us to grasp facets and dimensions of this construct. For example, Shen’s (Citation1975) iconic work suggests three forms of scientific literacy: practical, civic and cultural. The first one refers to the use of scientific and technological knowledge to resolve practical problems (related, for example, to basic human needs) and, consequently, to improve living standards. This form of scientific literacy is mostly related to the dissemination of information. Civic scientific literacy involves awareness of public issues in science and technology – such as environmental pollution and food quality – and the full participation of citizens in democratic dialogue around them. Cultural scientific literacy is described as the enjoyment of certain aspects of science and the understanding of science as located within other human and cultural productions.

Viewing scientific literacy as a continuum, Roberts (Citation2007, p. 730) proposed two visions that communicate with each other. Vision I, located at one extreme of the continuum, involves the understanding of the products and processes of science. Vision II, situated at the other extreme, derives from situations with science issues that one can encounter as a citizen. Regarding Robert’s work, some have advocated for the inclusion of a Vision III related to scientific engagement (Sjöström & Eilks, Citation2018) and, therein, to ethical and political attitudes about science and technology issues. Through these different views and interpretations of scientific literacy, we observe a movement from basic forms – related to acquiring and understanding facts and concepts (products of science) – to more complex views that articulate a broad and critical comprehension of the nature of science, its socio-political contexts and positioning and attitudes about science and technology issues.

In tandem with these ideas, scholarly works in science education have focused on the development of capacities and skills that will help citizens of contemporary societies participate in decision-making and sociopolitical engagement (Aikenhead et al., Citation2010; Bencze, Citation2017; Dos Santos, Citation2009; Hodson, Citation2014; Roth & Barton, Citation2004). For Hodson (Citation2014), commitments to sociopolitical action represent radical and politicised forms of scientific literacy that would enable people to pursue solutions for societal problems. Similarly, Dos Santos (Citation2009) argues that connections between more politicized forms of scientific literacy and science education have the potential to transform inequitable social realities (particularly in this globalized world where the local tends to be disregarded) and empower individuals, and collectives, to pursue social and environmental transformation.

Inspired by a Freirean perspective, Marques et al. (Citation2017) identify scientific literacy as a process, involving dialogue between experiential and scientific culture, appropriation of knowledge (related to scientific concepts, nature of science (NOS) and science, technology, society and environment (STSE) perspectives) and social participation (involving decision-making and social transformation). In their view, scientific literacy should promote epistemological consciousness and should be integrated into social projects involving, ethics, respect, tolerance, social justice and democracy. Pedretti and Nazir (Citation2011) reframe the meaning of scientific literacy through the lens of STSE education. They describe six STSE currents that speak to a range of ideologies and practices that embrace broader understandings of scientific literacy. In particular, their emphasis on socio-cultural and socio-ecojustice perspectives informs more recent conversations about what it means to be scientifically literate.

While we acknowledge the relevance that progressive views of scientific literacy bring to science education practices, particularly in the formal sector where they have primarily emerged, we wonder about their impact in informal sectors, and specifically the science museum landscape.

Scientific literacy, sustainability and science museums

Connections between scientific literacy and science museums are longstanding and evident in the literature (e.g. Bandelli, Citation2014; Bell et al., Citation2009; Christensen et al., Citation2016; Henriksen & Frøyland, Citation2000; Hodder, Citation2010). However, recently institutional goals and purposes have been questioned and scrutinized in light of scientific literacy perspectives (e.g. Hine & Medvecky, Citation2015; Pedretti & Navas Iannini, 2020; Rennie & Williams, Citation2006), and their relevance reconsidered in our increasingly ‘troubled world’ marked by environmental crises and degradation (Janes, Citation2009). By revisiting the practical, cultural, economic and democratic arguments for scientific literacy, Henriksen and Frøyland (Citation2000) question major contributions of science museums. In so doing, they compiled a list of possible new goals for these informal institutions that reflect civic aspects of scientific literacy. These goals create a space for considering museums as public service institutions, meeting places, arenas for public debate, dialogue institutions and contributors to the resolution of global challenges. Similarly, Achiam and Sølberg (Citation2017) analyse how science museums are responding to calls for change. They identify cultural, social, networking and political meta-functions of these institutions, alongside more traditional functions, such as researching, disseminating science, educating and preserving. According to Rennie and Williams (Citation2006, p. 793), expanding science museums’ roles and mandates to include dialogue, problem-solving and citizenship ‘would enable them to make a greater contribution to the practical and civic aspects [of scientific literacy]’. Rennie and Williams suggest utilizing scientific knowledge to solve practical problems while promoting awareness of public issues in science and technology and full participation of citizens in democratic processes.

In expanding science museums’ roles and mandates, institutions have been called to engage with education for sustainable development (Evans & Achiam, Citation2021; Janes & Sandell, Citation2019) and to consider transformative practices related to society and environment (see, for example, Barrett & Sutter, Citation2006). When considering public education for sustainable development, Reickmann (2020, p. 39) refers to competences that ‘enable and empower individuals to reflect on their own actions by taking into account their current and future social, cultural, economic and environmental impacts from both a local and a global perspective’. Similarly, Cloud (Citation2014, p. 1) discusses the need to foster knowledge and ways of thinking ‘that society needs to achieve economic prosperity and responsible citizenship while restoring the health of the living systems upon which our lives depend’. Cloud (Citation2014) further notes that (public) educational practices for sustainability should mobilize citizens to think critically about how to shape the future they want and to consider the unique value of sustainability. Similarly, Reickmann (2020) argues that education for sustainable development implies participation in socio-political processes, with the aim of promoting social and environmental transformation that could lead to create sustainable and healthy societies.

An examination of contemporary purposes of education for sustainable development allows us to establish a clear parallel with progressive views of scientific literacy (expressed, for example, in the voices of Hodson [Citation2014], and Sjöström and Eilks [Citation2018]). Particularly, we see connections across these two frameworks when it comes to (1) the notion of socio-political engagement with contemporary science and environmental issues that are socially relevant (critical Vision III of scientific literacy) and (2) the idea of pursuing social and environmental transformation (and justice) inspired by diverse forms of literacy (scientific, technological, environmental, economic, political, media and so on).

Vivid examples of education for sustainable development, and approaches that look to engage critically with, for example, the impact of our actions on our planet, can be found in the science museum world – reflected in educational programmes, institutional practices and exhibitions. One outstanding example is the Brazilian Museum of Tomorrow. Created in 2015, this space is described as an ‘applied science museum that looks to explore the opportunities and challenges that humanity will face in the upcoming decades through sustainability and co-existence lenses’ (Museum of Tomorrow, Citation2021a, para 5). Through permanent and temporary exhibitions and programming, the museum aims to provoke/engage visitors with complex questions (e.g. the Anthropocene) while, simultaneously, playing with the idea of producing collections (e.g. images, simulations) about what the future might hold (Museum of Tomorrow, Citation2021b).

Depending on the forms of representation chosen and the ways of conceiving the visitor experience, complex environmental and social topics – such as sustainability, climate change, deforestation – have the potential to move visitors to work towards social and environmental transformation. These reflections echo Cameron and Deslandes (Citation2011, p. 2011) words, when they talk about ‘the potential for museums and science centres to develop citizen capacities for living creatively with the opportunities and threats posed by climate change – as both physical reality and social discourse’. With these reflections in mind, we now consider the ways in which civic perspectives have permeated science exhibitions engaging with complex environmental issues.

Typologies of science exhibitions

The historical evolution of science centres and their exhibitions reflects different social purposes, ways of representing science and means of fostering visitors’ engagement (Amodio, Citation2013; Friedman, Citation2010; McManus, Citation1992; Pedretti & Navas Iannini, 2020). In this section, we discuss exhibition typologies (i.e. pedagogical, experiential, critical and agential) which are useful in helping us understand the terrain of exhibitionary practices (Pedretti & Navas, 2020), changing social roles and goals, and raises possibilities for enacting dimensions of scientific literacy.

We begin by recalling the work of Wellington (Citation1998) who characterized pedagogical and experiential exhibitions. The first type – pedagogical – refers to exhibition that look to teach something to visitors – e.g. facts about water pollution, population ecology or biodiversity. The second type – experiential– aligns with ideas of interactivity and hands-on displays. In this kind of exhibition visitors experience phenomena related to, for example, gravity, light, electricity, waves and so on. In our view, both typologies –pedagogical and experiential – reflect traditional ways of representing science due to their focus on content (principles, theories, phenomena, science ideas) and the absence of context (Pedretti & Navas Iannini, 2020).

In 2002, Pedretti expanded this typology by suggesting the emergence of critical exhibitions, those ‘that speak to the processes of science, the nature of science, and science and technology in its sociocultural context’ (p. 9). From a more dominant tradition of enlightening visitors, or promoting interaction with scientific phenomena, this exhibit typology works towards contextualizing science and technology issues, portraying their social implications and moving visitors to engage critically with them. Here we begin to see an expansion of mandates and social purposes within these public institutions.

More recently, Pedretti and Navas Iannini (2020) identify the emergence of a fourth typology involving agential exhibitions. Agential exhibitions are those that: (1) critically engage visitors with subject matter situated at the intersection of STSE (e.g. drug consumption, climate change, biodiversity loss, reproductive technologies, sexuality and so on); (2) consider visitors as political agents of change and transformation and (3) look to mobilize audiences to act at a personal, familial or societal level. Exhibits within this typology, rooted in action, tend to include novel spaces and practices such as dramatization, fictional stories, empathy building exercises, opportunities for decision-making, and spaces for conversations and deliberation. In sum, critical and agential exhibitions reflect a radical departure from the more traditional hands-on or interactive exhibitions and their preoccupation with immediate sensory experience, and explication of scientific phenomenon. They embrace and broach complex (at times controversial) subject matter mired in social-cultural, political, environmental and ethical considerations.

Earlier we noted pressing public environmental issues (that urge awareness, consideration, discussion, agency and full democratic participation) such as climate change, waste management, deforestation and sustainability are beginning to be included in the repertoire of science museums and their exhibitionary practices through more contemporary approaches. We suggest that some of these approaches reflect aspects of critical and agential emphases (see, for example, Cameron et al., Citation2013; Lyons & Bosworth, Citation2019; Pedretti & Navas Iannini, 2020; Sutter, Citation2008) and, Vision III of scientific literacy. Consider for, instance, The Human Factor exhibit displayed at the Royal Saskatchewan Museum. Inspired by eco-centric philosophy, this exhibit raised questions about industrialized worldviews and opened up opportunities for reflection and awareness about human activities that could lead to more sustainable ways of living (Sutter, Citation2008). Another example is KlimaX, a climate change exhibition hosted by Heureka The Finnish Science Centre. In this exhibit visitors ‘experience’ impacts of climate change by wearing knee-high yellow rubber boots (provided to them from the moment they enter the exhibit) and wading into the ‘ocean’, represented by the exhibit floor inundated with cold water melting from oversized ice blocks. Our World, is yet another example of a sustainability exhibition and the setting for our study. Below we describe Our World in more detail.

Setting the context: Our World

Our World began as a permanent exhibition at Science World (Vancouver, British Columbia). The focus was to portray how our everyday choices can affect our environment and the world. According to the museum professionals we interviewed, the first version of the exhibition – created in 2001, was originally characterized by a text-heavy approach (reminiscent of a pedagogical exhibition typology with a focus on teaching through the delivery of knowledge) that prompted the renovation of the space. The exhibit was then recreated and redeveloped with the intention of offering a less text-heavy emphasis. In its next iteration, Our World was renamed Our World: BMO Sustainability Gallery. Our visit occurred within this renovated space.

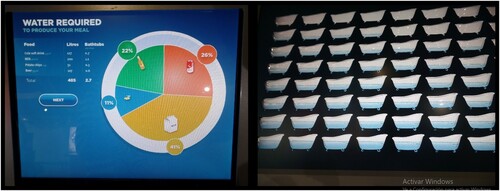

In its new form, the gallery kept the original idea of approaching a variety of issues related to our everyday choices and their impact on the environment – rather than choosing to focus on a single theme. This was reflected in the arrangement of panels, installations, games and interactives that visitors could encounter around the topics of water, food and energy consumption and waste. For example, the exhibit opened with ‘real time’ statistics reporting barrels of oil and litres of water consumed around the world and in Vancouver, respectively (). Passing the entrance, a graphic panel entitled Where in the world is my recycled waste? included a map reflecting the trajectory and amount of waste in transit from Vancouver to South Korea and China. On a digital screen, visitors could ‘recreate’ the kind of food that constituted their regular lunch and, then, obtain information about the amount of water needed to produce it (). On another interactive display, visitors could test their knowledge about sorting and recycling diverse items such as flip-flops.

Figure 2. Digital installation that calculates the amount of water used to produce our food. This amount is displayed through bathtubs filled with water. Credits: Ana Maria Navas Iannini.

Additionally, the exhibit included large cylinders full of toys and other objects that cannot be easily recycled – such as bells and purses. These were reminders of the quantity of waste that we produce (). Powerful photos depicting our disposal of garbage, and the subsequent impact on wildlife, were projected onto different walls of the exhibit (). Tables and chairs constructed with recycled materials (that visitors could actually use), shed light on the possibilities of reusing materials for household purposes. Our World also displayed a dialogue box where visitors were invited to comment on a daily fictional question related to consumption. Unfortunately, the exhibition is now closed permanently.

Methodology

Our study is positioned within a qualitative tradition. Employing case study as the research strategy (Flyvbjerg, Citation2011; Stake, Citation2000), we focused on museum professionals’ goals, expectations and tensions behind the (re)conceptualization of Our World. We then articulated these perspectives with understandings about scientific literacy and exhibition typologies. Sources of data include primarily semi-structured interviews with four museum professionals directly involved with the renovation and maintenance of the exhibit, as well as documents and artefacts related to the exhibition, observations, field notes and photographic records of the gallery.

Data collection

Data collection at Our World involved independent visits to the exhibit in 2015. Interviews were the primary source of data. We used and modified accordingly, a protocol we had developed for interviewing museum professionals in other case studies (see our larger research project, e.g. Pedretti & Navas Iannini, 2018 for more details). Originally, the protocol included 12 questions centred around three main topics: (1) conception and development of the exhibit (e.g. What do you think are the main goals of this exhibit); (2) relationships between the exhibit and the visitors (e.g. What do you expect visitors will ‘take home’ from their experience?); and (3) the roles of science museums, as envisioned by the staff (e.g. Do you think that science museums can be places for presenting and discussing sensitive topics? Please explain.). The changes we made to the protocol spoke to the specific topics and installations that were displayed at Our World (i.e. Do you think that science museums can be places for presenting and discussing sensitive topics such as waste management, food waste or water deprivation?). Due to the nature of the topics and images presented in Our World and, also, the history of the exhibition (i.e. a renovation, new floor location), we added a new question: How do you feel personally about the [new] exhibit? Have your feelings changed over time? How? Our hope was that personal perspectives and reflections would be shared and, from that, we could better understand goals and tensions related to the renovated exhibit and their articulation with scientific literacy and typologies of science museum exhibitions.

Using the adjusted protocol, we interviewed four museum professionals on site. Two of them were curators directed involved in the renovation of the space, and in the decision about the kind of displays and topics that could be preserved (from the previous version of Our World) and added to the new version of the exhibit. Additionally, we interviewed two facilitators working on and at the exhibit on a weekly basis. The facilitators were undergraduate students, trained by the curators to serve as mediators in the space. These interviews lasted between 40 and 80 minutes and were all audio-recorded.

On site we took pictures of the different displays, objects and caption labels, and produced field notes related to particulars of the exhibit. Regarding documents and artefacts, we gathered exemplars of daily questions asked in the exhibit’s dialogue box, maps and blueprints of the exhibit (these were sent to us by museum staff prior to our visit).

Data analyses

In our first analytical stage, the interaction with data – verbatim interview transcripts, field notes and documents – occurred through constant comparative analysis method (CCA), (Fram, Citation2013). Borrowing from O’Connor et al. (Citation2008), we view CCA as a process that ensures that all data are systematically compared to each other. In this iterative and inductive process, data reduction occurs through constant recoding (Fram, Citation2013). We started CCA by independently moving across our different sets of data and comparing each set to another. In this first round of coding, we started to identify codes that could be related to the ‘behind the scenes’ of the exhibit Our World, in other words, to expectations/goals or tensions particularly related to the renovation of the space. For example, excerpts of the conversations where museum staffers personally disagreed about specific aspects of the new exhibit or, expressed frustration and then hope that different views would be presented in a next iteration of the exhibit, were initially coded as tensions. Similarly, passages related to desired interactions between visitors and specific displays, were initially coded under expectations/goals. In a second round of coding, we collectively (re)examined all data initially coded under expectations/goals, and tensions in order to collapse codes and isolate emerging themes.

In a second analytical stage, we made use of deductive strategies that allowed us to connect our emerging themes with key theoretical constructs related to scientific literacy and typologies of science museum exhibits. For O’Connor et al. (Citation2008, p. 41) ‘It is the time and the process of this constant comparison that determines whether the analysis is deductive and will produce a testable theory or whether the analysis is inductive and will build a theory for a particular context’. In this case, we used perspectives related to progressive and traditional views of scientific literacy (e.g. Dos Santos, Citation2009; Hodson, Citation2014; Pedretti & Nazir, Citation2011; Shen, Citation1975) to interact with our data. Our intentions in using these perspectives were to articulate museum staff views with different conceptions/dimensions of scientific literacy and exhibition typologies identified in/through the literature and to consolidate major analytical themes. We felt compelled to move beyond our (re)telling of museum staff’s experiences in the context of renovating a sustainability-based exhibit. We saw this work as an opportunity to ask ourselves: What can we learn about sustainability exhibitions when we use a scientific literacy lens?

Findings

Museum professionals’ perspectives about Our World and in particular its renovation, revealed goals, expectations and tensions that we combined under two major topics: (1) redeveloping the exhibit and (2) reimagining the visitor experience. The first topic reflects complex decisions and choices about the nature, forms of representation and relevance of the contents and narratives displayed. The second topic presents aspirations and tensions that arose as the ideas of promoting visitors’ criticality, introspection and agency became part of the discourse concerning exhibition goals. More will be said about each topic, and their themes, in the following sections.

Redeveloping the exhibit: aspirations and apprehensions

Commitments to sponsors and to the community

While talking about the renovation of Our World, and the decisions behind content and narratives, the museum professionals referred to commitments to sponsors that provided funding. That was the case with BC Hydro, a Canadian electric utility in the province of British Columbia:

We received some money from BC Hydro to redevelop our energy exhibits … When it was moving downstairs I said ‘well … it was decided [that] we really need to develop it all together’. So, I said ‘we will bring the electrical end energy stuff down here’ … another area that was really weak before, in Our World, was the water area … (Interview, curator)

The water exhibit, the waste exhibit, those things were kind of added on and re-imagined as part of this this installment (Interview, curator)

So we basically … we added the water area. We redid the water area. We redid recycling in here … (Interview, curator)

As described by facilitators and curators, the science centre also consulted with different members of the community during the renovation, with the aim of including local topics (and practices) that could be meaningful, especially for Vancouverites. This was the case of recycling:

I feel like they [curators] did a lot of outreach to the community … especially because this is such a … very environmentally conscious neighbourhood, it is very green. (Interview, facilitator)

We had discussions with people from city of Vancouver and Metro Vancouver and also private recyclers … Recycling is a very competitive business … They do not like to issue out how much they recycle and who they recycle to … but we managed to get some information from them. (Interview, curator)

In search of balance and relevance

In several instances, the museum team spoke at length about content they wished to have included to achieve relevance and a better balance across topics. They described financial constraints such as available funding as one of the barriers that impacted the content and final look of the exhibit; this was particularly prevalent with regards to some displays that did not reflect the intensions of curators:

I am not really crazy about that game over there [referring to the compost game]. That game was just … last minute. We did not have very much money … so we did basically a version of operation where you took stuff - food items out of the compost or out of the landfill and put them in the recycling bin, so they could be recycled. I think if I could have done something on how much food does the average family waste … That might be interesting. (Interview, curator)

I think that they have lots of different stuff about power generation … tons of stuff about that. I think that they could have more information, maybe, about … environmental impact of different foods that you eat … Because, I recently became aware of the amount of carbon and water it takes … for the dairy industry and agriculture industry to function. It is crazy! And I feel like it is one of those things that not a lot of people know about. (Interview, facilitator)

I think everyone agrees that [the exhibit] is a good idea, but I think, sometimes … this incarnation of the gallery … is still relatively new compared to the rest of Science World … maybe, people do not see its importance yet, whereas I think everyone can agree that in theory it is important. (Interview, facilitator)

For me, climate change is a really big [issue], well it is the biggest issue facing humans in the next while and, so, I think of having something a bit more tied into that [would be important] … I think part of it, for me, as an environmental educator and a science educator, is not [that] we are trying to get people to become scientists … (Interview, curator)

The exhibits [where engagement] was happening most were the ones that have … the simplest message … so one was the compost game and the recycling trash or recycle sorting game. These ones … have the highest breakthrough level but that is also because that is what people understand the most already … They are able to say ‘hey! I do this at home and I know what one goes in the trash or the recycling’. (Interview, curator)

A hopeless angle

According to the museum team, the renovated Our World tended to focus on the negative aspects of our choices and the ways they relate to the environment (e.g. all that we waste, all that we consume), thereby disregarding the more positives perspectives (for example, what could be done to live in more sustainable ways or what could we offer to future generations). As acknowledged by one of facilitators, the exhibit is ‘pretty depressing right now … [there are] … a lot of negative things, sad facts in there. It’s horrible! You’re like ‘oh my goodness!’ (Interview, facilitator). In moving forward, the staff expressed their desire to transform some of the negative and even hopeless angles displayed into positive contexts or stories:

If you go up to a different gallery and you pull a ball and it does a thing … it is like ‘oh that’s a cool physics lesson!’ but, also I got to do that cool thing. Whereas here, you might play a game and it is like ‘we’re all going to die!’. So, I am fighting that initial frustration of ‘what can I even do?’. (Interview, facilitator)

Some of the upcoming changes that we are looking for are … making it … having a bit more of a positive spin … not ‘look what you’ve done with the choices you’ve made’ … but ‘look what other people are doing around the world’. So, comparing to other countries, organizations or individuals that are making positive environmental impact because of the choices that they are making – because of this understanding – we have this global connection. (Interview, curator)

I get a lot of inspiration from hearing about what individuals are doing and so I think that that is currently missing in terms of … the ‘hero’ stories … Current cool green technology is a really good way of engaging people because it is also … exciting … (Interview, curator)

It’s … putting the power in people’s own hands … I am very attached to the subject matter … that is where my passion lies … environmental education and getting people keen about sustainability … and, yeah, there is definitely some things I really love about it and I think are successful and then other things where I see we can do it differently. As educators we are realizing that we need to move from this behavioralist perspective, where … you … we … the teacher tells you what you should do and, instead, it is that idea of … ‘Hey! We are all in this together’ What should we do? Look at what some other people are doing.’ How do we engage in this subject matter and make it a little more empowering? I think it is what I would like to see … not feeling like it is hopeless. (Interview, curator)

Reimagining the visitor experience: aspirations and apprehensions

Accessing new, updated and trustworthy information

On several occasions the Our World’s team referred to the exhibit as a space that could move visitors to access updated information about environmental issues (and research) and contexts for their choices and behaviours:

I think it was a little bit ‘journalistically’ what we wanted to do … expose people a little bit more about [news] … current affairs … So just a little bit more than what you normally hear about recycling or about use of water and so on. It was just [about] trying to provide people with a little bit more information, possibly for context … Like this one, that wall graphic over there ‘How much food does an average family throw out?’. That came from a fabulous British study where they went through everybody’s garbage and they just said ‘well, these grapes are still good’. You know, they went back and basically did some stories, very simple. (Interview, curator)

I think he [referring to another staff member] was just trying to also incorporate … new science that ties into the themes of Our World … A topic that is so dynamic, it is constantly changing, so the information that we have about the environment is constantly changing. Our impacts are changing. The technologies we are using are changing … And so, I think that one of our goals was just trying to keep a little bit more up-to-date in terms of … exciting new science, new technologies or ideas that are going on right now. (Interview, curator)

In providing information that is not necessarily new in terms of research and developments (although it may be for visitors), there was a deliberate attempt to make knowledge more accessible and attractive in order to catch visitors’ curiosity and lessen the gap between scientists and the public in terms of knowledge:

There is this kind of mistrust in science that makes me really uncomfortable … So, I want it [the exhibit] to be science storytelling, in terms of ‘scientists are studying these things because they are really passionate and they are worried about the planet and their communities’ and that kind of thing … trying to make it a little more real. (Interview, curator)

[We] try to provide them [the visitors] with some fascinating information or something that they think they will find interesting and just peak their curiosity. Like ‘how much water goes into your meal’. So … it may change their behaviour … but the first thing is maybe [that] they want to know more. … try to peak that curiosity. (Interview, curator)

In this spirit, educators and facilitators also made information available for visitors through resources found outside of the exhibit (for example on the science centre’s website). Efforts to keep Our World updated are part of the team’s work, as the science facilitator acknowledged:

Me and the other staff who work in Our World … if you see an interesting … newspaper article or whatever, you can bring it to the attention of the exhibit’s curator and then we … keep the exhibit up to date. Sometimes guests will come up and say ‘oh, have you heard about this story?’ and, then, that is a great way … a great resource to be able to say ‘I’ll look into it!’. (Interview, facilitator)

Promoting awareness

A clear aspiration for the visitor experience was the need to raise individual awareness about complex environmental issues that are directly related to the impact of human choices/activities on the world around us. This was expressed by two staff members:

I would say [that the goal of the exhibit is] to get people thinking about and being aware of the impacts that their choices, that they make every day, have on the Earth. (Interview, facilitator)

I hope that they [the visitors] are taking home the message that … ‘all of us are creating an impact’ … There are over seven billion people on planet earth, we need to treat the Earth and each other well. (Interview, curator)

The expectation of generating awareness was tied to new displays that could affect visitors through powerful images, statements, facts and statistics:

In the gallery there is a picture of the contents of an albatross’s stomach … people might not be too happy with that. And … as I was saying before … you might feel a little humbled by what you haven’t done yet. (Interview, facilitator)

Food being wasted in Canada 3122326156 Kilograms (Field notes, information displayed and counting on electronic panel)

Although the renovated version of the exhibit was intended to impact visitors and generate awareness, there were concerns about risky choices related to content and its forms of representation and how they might impact the experience of the public in the space. In selecting some of these new resources to be included in the exhibit, a curator explained part of the process:

We do not just put up something because we think it is important. I mean we will definitely test the community. We do survey … on the risk … we surveyed the public about that Chris Jordan shot [of the dead albatross], and I think I had four or five eight-and-a-half by elevens of different shots that Chris let me use. And [I] just said ‘which one?’ … We came up with this [one] … Same with the sexuality [exhibition]. I showed a lot of people nude pictures of people and said ‘are you comfortable with this?’ And about 80% said ‘not a problem at all’. (Interview, curator)

Fostering change and agency

In the spirit of moving visitors to be forward thinking (and, to some extent, transitioning from awareness to action), the museum team decided to combine global and local perspectives related to consumption and waste. This is illustrated in the words of the curators and facilitators:

I think for Our World, particularly, it is just what is going on in Vancouver right now, more or less. I think that there are … international ties in the gallery but I think there are quite a few local ties as well … which are important. (Interview, facilitator)

Currently, I think [that] part of it is trying to engage people in the consequences of their daily choices and how the things that we wear, the things that we buy, the things that we play with and what we eat … all of that has an environmental impact … and that has a global impact as well … plastic waste in the ocean, how [scarce] … accessible fresh water is on planet Earth and how much we use compared to other places in the world. The choices we are making go beyond our day-to-day life. (Interview, curator)

By including local and global perspectives, the museum staff hoped to broaden the visitor’s vision regarding cause–effect relationships and human impact on the environment. The museum team spoke of their intentions to problematize personal perspectives:

I think the exhibit was trying to change people’s perspective on things a little bit. Give them a little bit more information about things. I guess maybe try to break away from the standard kind of rhetorical phrasing that is used around sustainability … Let us just say, looking a little bit deeper about recycling, water use … We always say ‘well, you know, you should stop, we should reduce this and this and this’ and then we think ‘okay then’. In some ways how does that actually affect your life? (Interview, curator)

Other galleries … are there to sort of bring to light science concepts just like physics concepts … We do chemistry shows and things like that … This one [Our World] is really asking you to reflect inward and think about, ‘okay, well, I do throw a lot of stuff out and, yeah, I did let vegetables rot in my fridge’ and … those kinds of choices that you are making and how they connect. So, I think it challenges you to look inward and really see that there are things that you can … that everyone can do to improve their environmental impact and have a positive change … Some people may feel challenged in terms of their personal choices. (Interview, curator)

I have had one or two visitors who came up to me and said ‘wow, I had no idea about this’ [pointing at a display] or the things about waste and all the toys … They were there with two kids and they said ‘well, next time you ask me for a new toy, think about how many toys are thrown out. ‘Maybe we should stop buying so many new toys’. So … I have seen it start some dialogues, between families that, if they remember it the next day, it could definitely change their lives. (Interview, facilitator)

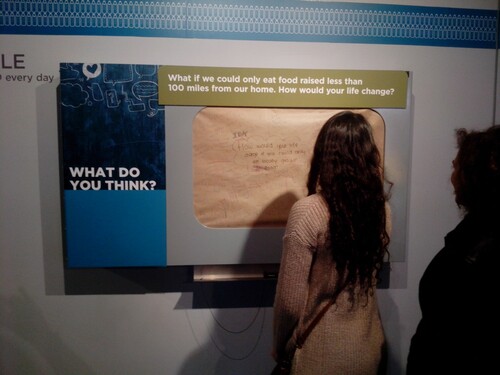

Aligned with these initiatives, the curators decided to include a dialogue box in the exhibit used to explore and/or challenge visitors’ beliefs through complex questions that posed different fictional scenarios. These questions varied from day to day as the following example and illustrate: ‘How would your life change if you could only eat locally produced food?’ (Field notes, question written in the dialogue box, 23 October 2015) ().

The introspective scope of the dialogue box was emphasized by the curators:

[The dialogue box] was a way that you provide some sort of profound question and then watch for people’s response to it … and, then you know, to challenge that. (Interview, curator)

We do end up getting some pretty engaging answers on there [the dialogue box] and people really thinking about the subject and really on polar opposite sides of the spectrum … Sometimes they are like ‘ugh!’ … We change up the questions, we have a whole series of questions there. Just thinking right now it is the local food ones and some people say ‘I would never give up eating pineapples and da da da’. And then other people are like ‘it would be great!’ and ‘I will get all my stuff at the farmer’s market and it would make life easy’. (Interview, curator)

Through these initiatives, curators and educators hoped that ultimately visitors would develop agency (and hope) outside the science centre:

I want people to take away that ‘it’s not too late, look what we can do!’, ‘look what people are doing around the world!’ … and because we are so connected, it can actually be very positive because we can learn from our own mistakes and other people’s mistakes and also other people’s gains. What others are doing around the world … that works really well. (Interview, curator)

Maintaining a neutral space?

Museum staff expressed concerns about ‘finger pointing’. In our conversations, some facilitators expressed struggles about the best way of approaching and engaging visitors with difficult conversations about the topics displayed:

One of the things I am always nervous about is … I do not want to go and … rant at a visitor and say … ‘well you should be doing this and you should be doing that’ because it is going to have the opposite effect on them and they are not going to feel [well] … Things like asking people to change their diet, remove red meat from it … some people would passionately say ‘no, I do not want to do that’ … So, I feel … the way that it [the exhibit] presents it is like ‘here is some information and you can do what you want with it’. So I like that component of it. (Interview, facilitator)

The way that it is [currently] done, it is meant to be a kind of a neutral territory. It is not necessarily condemning anything as being bad. I mean … it is a good place … you can come from a really objective perspective, and instead of saying that something is good or bad necessarily, just giving, presenting facts and [the] guest[s] can, maybe, make up their own mind[s]. (Interview, facilitator)

You can take an image and hardly add any words to it and it tells you something about it … We were actually going to use some shots that were a little bit more punchy than this one [referring to the picture of the albatross]. There was a fear that some people were going be freaked out by it. (Interview, curator)

Discussion and implications

Our findings suggest that the renovation and (re)conceptualization of this gallery illustrates an attempt to move from a pedagogical to a critical and agential agenda, through which progressive views of scientific literacy could be at play. This movement comes with delicate decisions, negotiations and choices about goals, content, context, forms of representation and ways of fostering visitor engagement. Below we discuss this movement, and its implications for exhibitionary practices and for deepening understandings of scientific literacy dimensions.

The role of information

Disseminating information was a key component in the original version of Our World, and was still relevant in the renovated version of the exhibit. As illustrated in the findings, the museum team hoped that visitors could access updated and well-grounded information provided through the exhibit’s displays, and also, through online resources. They spoke about keeping more up-to-date information, sharing exciting new science, and new technologies, and the dynamism of that knowledge. Their efforts relate to the practical and cultural dimensions of scientific literacy described by Shen (Citation1975) that involve (1) possession and use of scientific knowledge and (2) enjoyment of science as a human endeavour. In this particular exhibit, the first dimension is reflected in the representation of data, statistics and facts (that visitors can access, learn about, and incorporate into their knowledge base). The second dimension involves displaying techno-scientific developments, updating information, and providing knowledge about contemporary advancements such as wind turbines and fuel cells. They hoped that these efforts would serve to enhance visitor excitement, curiosity and appreciation.

The need for information is an important and needed facet of scientific literacy and a legitimate goal for science exhibitions. However, dissemination of information in a passive transmissive way, is not enough when it comes to envisioning contemporary scientific literacy practices in the science museum world. A pedagogical agenda might be useful in a science exhibit if the information that is provided is relevant, robust and timely (Levinson, Citation2010) and more importantly, if it can support other agendas (such as critical or agential goals). There are times, however, when sponsorship issues may impose limits about what knowledge or narrative, for example, is included or privileged, not included, and/or celebrated. As it happens, in Our World, finding balance and relevance for certain topics was challenging, especially in an era when funding (recall the ‘BMO’ portion of the exhibit’s title) and exhibition production intersect.

We argue that an over-reliance on knowledge or content at the expense of other domains of scientific literacy in informal settings (expressing, for example, one’s position, attitudes and agency) is problematic. More progressive views of scientific literacy (that articulate access to information and content with issues of citizenship and civic participation) move us to consider more contemporary perspectives of the social roles and purposes of science museums (Henriksen & Frøyland, Citation2000; Stocklmayer et al., Citation2010; Pedretti & Navas Iannini, 2020) and calls for the articulation of different typologies within a single exhibition. More will be said about this in the following sections.

Navigating the in-between positions

Although the renovated Our World was not intended to become an agential exhibit in the sense of explicitly questioning visitors’ beliefs or inviting visitors to engage in debates and actions about environmental topics, the articulated exhibit goals did approach issues with potential to be contentious and provocative. In the new version of the exhibit, the museum team navigated a number of in-between positions that implied difficult choices and carried implications for exhibition practices. These in-between positions become spaces that require hard work amongst museum staff as they negotiate aspects of content, messaging, production and visitor experience (Eikeland & Frøyland, Citation2020).

At Our World, staff hoped that visitors would interrogate and eventually change their own beliefs and practices while cautioning against finger pointing (echoing the desire to maintain a neutral space). In another example, the goal to promote awareness about critical environmental issues is primarily driven by shocking/powerful statistics, images, and content alongside staff articulating concerns about leaving visitors feeling hopeless. These tensions reflect, to some extent, the difficulties of moving from traditional interpretations of scientific literacy to more critical and progressive views that encompass epistemic consciousness (Marques et al., Citation2017) and epistemic capacity (Hine & Medvecky, Citation2015). Epistemic capacity (in this context) refers to the development of skills that would allow visitors/citizens to not only understand the issues posed by the exhibit but, also to asses them, make informed decisions and (potentially) act.

Other in-between positions involve cause–effect relationship between humans and nature, and tensions concerning the best ways to engage visitors with (and move them to consider) ecological world views. Borrowing from Shume’s (Citation2017) work, it is interesting to note that cause–effect perspectives in the exhibit have potential to critique and challenge anthropocentric views of nature, including technocentrism (us over nature) and egocentrism (us vs. nature). This potential could be seen in the powerful exhibit discourse about using and exhausting different kinds of natural resources such as water and food. However, other views such as biocentrism could reflect more positive ways of envisioning the ideas (and ideals) of humans-within-nature and humans-in-nature. Here, we can begin to see promising pathways for (re)envisioning these latter relationships and ideals, and for developing and/or (re)imagining environmental and suitability exhibitions.

Towards civic responsibility

Over the years, we have been considering how socio eco-justice and socio-political perspectives (e.g. Dos Santos, Citation2009; Hodson, Citation2014; Pedretti & Nazir, Citation2011; Sjöström, Citation2019) could be embraced by exhibits that directly approach sensitive and complex environmental issues. Recalling Pedretti and Nazir’s (Citation2011, p. 608) work, a socio-ecojustice perspective involves ‘[c]ritiquing/solving social and ecological problems through human agency or action’. Accordingly, this perspective considers citizenship and civic responsibility to produce positive social and environmental transformation. For Pedretti and Nazir, potential strategies for embracing a socio-ecojustice perspective include the use of socio-scientific issues, the conception and development of community projects, and the development of action plans. Borrowing from Barrett and Sutter (Citation2006), we argue that Our World aimed to promote behavioural modification primarily in terms of individual actions – how to better recycle; how to choose products more wisely; how to make better choices regarding the food you consume, the amount of energy you use, the waste you produce. Museum staff hoped that visitors would become personally responsible citizens (Westheimer & Kahne, Citation2004), acting responsibly in their community, and making better and fairer choices regarding the environment.

In this context, we wonder how exhibits delving into complex environmental issues might more fully embrace opportunities to approach civic responsibility – a feature that is at the core of socio-ecojustice perspectives and agential exhibits – alongside other aspects of citizenship such as the participatory and the justice-oriented profiles (Westheimer & Kahne, Citation2004). These two profiles of citizens involve critically assessing political, economic and social structures beneath the surface of the issues and engaging in organizing collective efforts to generate social and environmental change. Extending these ideas to the science museum landscape, we ask: Would it be possible (and desirable) for science museums to create exhibitions that invite small group of visitors to experience together, parts of an exhibition and share their responses to it? Could groups of visitors be included in an activity that implies pondering positions about a particular environmental concern and outlining a plan for action?

We can begin to see possibilities for fostering stewardship (Janes, Citation2009) through exhibitionary practices. This implies moving from individual perspectives to more explicit articulation and attention to collective pathways for assuming and acting towards long-term care of the environment. This is no easy task. For example, the focus on promoting awareness on cause–effect relationships between humans and environment, as described in Our World, generated tensions in some staff members who would like to have seen a more positive approach (and even more agency) versus the negative and, somehow, hopeless perspective that the exhibit tended to convey. A more positive spin – in terms of courting other possibilities of citizenship – could be achieved through more collective, action-oriented approaches for sustainable and environmental education (Barrett & Sutter, Citation2006) enacted by/through the exhibition and its visiting publics.

Final thoughts: civic scientific literacy and museum practices

Progressive views of scientific literacy (when enacted in science museums’ practices) call for critical and agential exhibitions and for spaces and practices that aim to engage the audience in reflection and action about the complexities of the issues posed. It is a challenge, however, to imagine how progressive views of scientific literacy can be embraced through exhibitionary practices. (Re)conceptualizing an exhibit to include elements of participation, change and agency are often desirable, but can be fraught with challenges. These approaches represent, to some extent, potentially ‘dangerous’ terrains due to what is implied when: (1) going beyond the surface of the issues, and opening up a space to consider and engage with the social, political and economic forces involved (Janes, Citation2009; Pedretti & Nazir, Citation2011; Westheimer & Kahne, Citation2004); (2) developing deep and complex critiques (Sperling & Bencze, Citation2015); (3) openly challenging staff (and visitors) to examine their core attitudes, beliefs and practices (Barrett & Sutter, Citation2006; Kollmann et al., Citation2013; Ng et al., Citation2017) and (4) adopting an outward focus from which the visitors, and broadly speaking the community, provide feedback to the institution (Barrett & Sutter, Citation2006). Our work has prompted us to consider how progressive views of scientific literacy (involving civic perspectives) could be envisioned in theory and practice. In so doing, we offer some concluding thoughts.

Firstly, we are reminded of the concept of ‘productive struggle’ that can occur for staff (and visitors too) when engaging with more complex subject matter and participatory visitor engagement strategies. Productive struggle implies that people are engaged in thinking critically and probably experiencing some emotional disequilibrium (D’Mello et al., Citation2012; Ng et al., Citation2017). This concept provides a powerful way forward as we consider staff (and visitor experiences), and the inherent tensions that emerge. Productive struggle can be problematic and uncomfortable as museum staff negotiate, for example: new exhibitions that approach controversy; decisions around content to be included/excluded or privileged/not privileged; funding issues; and institutional positioning with respect to the public gaze. However, these moments are necessary and provide opportunities for institutional growth, re-prioritizing of goals and possibly re-interpretations of what it means to be scientifically literate (Achiam & Sølberg, Citation2017; Henriksen & Frøyland, Citation2000; Pedretti & Navas Iannini, 2020).

Secondly, when displaying critical and complex environmental issues the role of knowledge is nuanced. Exhibitions that are willing to engage in sensitive science and technology topics, tend to promote awareness, generate introspection and foster dialogue opportunities. By implication, science museums would need to provide information that is relevant and useful for the communities that attend (Navas Iannini & Pedretti, Citation2017). Similarly, Levinson (Citation2010) reminds us of the importance of relaying robust, timely and relevant knowledge, particularly when it can support other dimensions of engagement such as deliberation and praxis (potentially, as part of the visitor experience) - hallmarks of critical and agential exhibitions. The provision of useful information, within a pedagogical emphasis, needs to be combined with other agendas that require active and critical involvement. Critical and agential exhibition add the potential to foster other skills associated with more progressive views of scientific literacy such as formulation of own opinions, decision-making, weighing of evidence and agency.

Thirdly, issues of neutrality need to be (re)considered when thinking about science exhibitions that are willing to go beyond the surface and explore, in deeper ways, the social, political and economic contexts in which complex topics are immersed. Hodson’s (Citation2014) reflections about introducing critical themes in science education are useful to discussions about whether science museums should keep or aim to maintain neutral positions regarding the issues they display. For Hodson (Citation2014, p. 74) neutrality is a position that threatens credibility as ‘[t]he key point is that all views embody a particular position, and that position needs to be rationalized and justified if indoctrination is to be avoided’. Science museums have been often seen as repositories of truth, places that could be related to a search for neutrality and ‘objectivity’. However, authors such as Cameron (Citation1971, Citation2012), Cameron and Kelly (Citation2010), Henriksen and Frøyland (Citation2000), Hine and Medvecky (Citation2015), Mazda (Citation2004), and Rennie and Williams (Citation2006) have called science museums to become forums for rich conversations - places that promote questioning, criticality and yes, scepticism. In this context, we argue that if it is difficult for science museums to assume and defend a specific position (due primarily to the different voices articulated in the mounting of exhibits including CEOs, curators, sponsors, community, etc.) other pathways could be taken. For example, exhibits that focus on critical science and technology themes could consider affirmative neutrality as a way of (1) acknowledging different positions, voices, points of view and arguments around the issues; (2) portraying more realistic science and technology perspectives and deeper understandings on the complex interactions among science, technology, society, and environment and (3) raising the (social, cultural, economic, political) implications of scientific and technological advancements according to the interest of different social actors.

In conclusion, we acknowledge that embracing progressive views of scientific literacy through exhibitionary practices is hard work. Our study, however, suggests that in spite of barriers and risks that might accompany such a shift, science museums, worldwide are increasingly engaging in discussions and practices that reflect a growing trend to engage visitors in different and critical ways with complex topics such as environmental sustainability, climate change and biodiversity loss. Whether creating a new exhibition, or re-imagining and renovating an existing exhibition, it can be done. Amidst the challenges of embracing more progressive views of scientific literacy in/through science exhibitions, we see and welcome the possibilities for moving forward and fostering different dimensions of public engagement and scientific citizenry around science, technology and environmental issues that matter.

Acknowledgements

We thank Daniel James Atkinson for his enthusiasm and support in collecting data for this research. We are grateful to the Science World staff who so generously welcomed us into their space and provided us with all the opportunities and conditions for conducting data collection.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Achiam, M., & Sølberg, J. (2017). Nine meta-functions for science museums and science centres. Museum Management and Curatorship, 32(2), 123–143. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2016.1266282

- Aikenhead, G., Orpwood, G., & Fensham, P. (2010). Scientific literacy for a knowledge society. In C. Linder & A. MacKinnon (Eds.), Exploring the landscape of scientific literacy (pp. 28–44). Routledge.

- Amodio, L. (2013). Science communication at glance. In A. M. Bruyas & M. Riccio (Eds.), Science centres and science events (pp. 27–46). Springer.

- Bandelli, A. (2014). Assessing scientific citizenship through science centre visitor studies. Journal of Science Communication, 13(1), C05. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.22323/2.13010305

- Barrett, M. J., & Sutter, G. C. (2006). A youth forum on sustainability meets the human factor: Challenging cultural narratives in schools and museums. Canadian Journal of Science, Mathematics and Technology Education, 6(1), 9–23. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14926150609556685

- Bell, P., Lewenstein, B., Shouse, A. W., & Feder, M. A. (2009). Learning science in informal environments: People. Places, and Pursuits. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17226/12190

- Bencze, L. (2017). Science and technology education promoting wellbeing for individuals, societies and environments: STEPWISE (Vol. 14). Springer.

- Cameron, D. (1971). The museum, a temple or the forum. In G. Anderson (Ed.), Reinventing the museum (pp. 61–73). Altamira Press.

- Cameron, F. (2006). Beyond surface representations: Museums, ‘edgy’ topics, civic responsibilities and modes of engagement. Open Museum Journal: Contest and Contemporary Society, 8.

- Cameron, F. (2012). Climate change, agencies and the museum and science centre sector. Museum Management and Curatorship, 27(4), 317–339. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2012.720183

- Cameron, F., & Deslandes, A. (2011). Museums and science centres as sites for deliberative democracy on climate change. Museum and Society, 9(2), 136–153.

- Cameron, F., Hodge, B., & Salazar, J. F. (2013). Representing climate change in museum space and places. WIRES Climate Change, 4(1), 9–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.200

- Cameron, F., & Kelly, L. (2010). Hot topics. Public culture, museums. Cambridge Scholars.

- Christensen, J. H., Bønnelycke, J., Mygind, L., & Bentsen, P. (2016). Museums and science centres for health: From scientific literacy to health promotion. Museum Management and Curatorship, 31(1), 17–47. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2015.1110710

- Cloud, J. (2014). The essential elements of education for sustainability (EfS) editorial introduction from the guest editor. Journal of Sustainability Education, 6, 1–9.

- D’Mello, S., Dale, R., & Graesser, A. (2012). Disequilibrium in the mind, disharmony in the body. Cognition & Emotion, 26(2), 362–374. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2011.575767

- Dos Santos, W. L. P. (2009). Scientific literacy: A Freirean perspective as a radical view of humanistic science education. Science Education, 93(2), 361–382. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.20301

- Eikeland, I., & Frøyland, M. (2020). Pedagogical considerations when educators and researchers design a controversy-based educational programme in a science centre. Nordic Studies in Science Education, 16(1), 84–100. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5617/nordina.7001

- Evans, H. J., & Achiam, M. (2021). Sustainability in out-of-school science education: Identifying the unique potentials. Environmental Education Research, 27(8), 1192–1213. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2021.1893662

- Flyvbjerg, B. (2011). Case study. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (pp. 301–315). SAGE.

- Fram, S. M. (2013). The constant comparative analysis method outside of grounded theory. The Qualitative Report, 18(1), 1–25.

- Friedman, A. J. (2010). The evolution of the science museum. Physics Today, 63(10), 45–51. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3502548

- Henriksen, E. K., & Frøyland, M. (2000). The contribution of museums to scientific literacy: Views from audience and museum professionals. Public Understanding of Science, 9(4), 393–415. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1088/0963-6625/9/4/304

- Hine, A., & Medvecky, F. (2015). Unfinished science in museums: A push for critical science literacy. Journal of Science Communication, 14(2), A04. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.22323/2.14020204

- Hodder, A. P. W. (2010). Out of the laboratory and into the knowledge economy: A context for the evolution of New Zealand science centres. Public Understanding of Science, 19(3), 335–354. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662509335526

- Hodson, D. (2003). Time for action: Science education for an alternative future. International journal of science education, 25(6), 645–670.

- Hodson, D. (2014). Be part of the solution learning about, from activism. In L. Bencze & S. Alsop (Eds.), Activist science and technology education (pp. 67–98). Springer Netherlands.

- Janes, R. R. (2009). Museums in a troubled world: Renewal, irrelevance or collapse? Routledge.

- Janes, R. R., & Sandell, R. (2019). Museum activism. Routledge.

- Kollmann, E. K., Reich, C., Bell, L., & Goss, J. (2013). Tackling tough topics: Using socio-scientific issues to help museum visitors participate in democratic dialogue and increase their understandings of current science and technology. Journal of Museum Education, 38(2), 174–186. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10598650.2013.11510768

- Levinson, R. (2010). Science education and democratic participation: An uneasy congruence? Studies in Science Education, 46(1), 69–119. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03057260903562433

- Lyons, S., & Bosworth, K. (2019). Museums in the climate emergency. In R. R. Janes & R. Sandell (Eds.), Museum activism (pp. 174–185). Routledge.

- Marques, A. M. C. T. P., Júnior, P. M., & Marandino, M. (2017). Alfabetização científica e crianças: As potencialidades de uma brinquedoteca. Enseñanza de las Ciencias: Revista de Investigación y Experiencias Didácticas, 1661–1666.

- Mazda, X. (2004). Dangerous ground? Public engagement with scientific controversy. In D. Chittenden, G. Farmelo, & B. V. Lewenstein (Eds.), Creating connections: Museums and the public understanding of current research (pp. 127–144). AltaMira Press.

- McManus, P. M. (1992). Topics in museums and science education. Studies in Science Education, 20(1), 157–182. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03057269208560007

- Museum of Tomorrow. (2021a). About. https://museudoamanha.org.br/pt-br/sobre-o-museu

- Museum of Tomorrow. (2021b). Exhibits. https://museudoamanha.org.br/pt-br/exposicoes

- Navas Iannini, A. M., & Pedretti, E. (2017). Preventing youth pregnancy: Dialogue and deliberation in a science museum exhibit. Canadian Journal of Science Mathematics and Technology Education, 17(4), 271–287.

- Ng, W., Ware, S., & Greenberg, A. (2017). Activating diversity and inclusion: A blueprint for museum educators as allies and change makers. Journal of Museum Education, 42(2), 142–154. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10598650.2017.1306664

- O’Connor, M. K., Netting, F. E., & Thomas, M. L. (2008). Grounded theory: Managing the challenge for those facing institutional review board oversight. Qualitative Inquiry, 14(1), 28–45. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800407308907

- Pedretti, E. (2002). T. Kuhn meets T. Rex: Critical conversations and new directions in science centres and science museums. Studies in Science Education, 37(1), 1–41.

- Pedretti, E., & Navas Iannini, A. M. (2020). Controversy in science museums: Reimagining exhibit spaces and practice. Taylor & Francis UK.

- Pedretti, E., Navas Iannini, A. M. (2018). Pregnant pauses, science museums, schools and a controversial exhibition. In R. Gunstone, D. Corrigan & A. Jones (Eds.), Navigating the changing landscape of formal and informal science learning opportunities (pp. 26–40). Springer.

- Pedretti, E., & Nazir, J. (2011). Currents in STSE education: Mapping a complex field forty years on. Science Education, 95(4), 601–626. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.20435

- Rennie, L. J., & Williams, G. F. (2006). Communication about science in a traditional museum: Visitors’ and staff’s perceptions. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 1(4), 791–820. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-006-9035-8

- Rieckmann, M. (2018). Learning to transform the world: Key competencies in education for sustainable development. Issues and Trends in Education for Sustainable Development, 39, 39–59.

- Roberts, D. A. (2007). Scientific literacy/science literacy. In S. K. Abell & N. G. Lederman (Eds.), Handbook of research on science education (pp. 729–780). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Roth, W. M., & Barton, A. C. (2004). Rethinking scientific literacy. RoutledgeFalmer.

- Shen, B. (1975). Science literacy. American Scientist, 63(3), 265–268.

- Shume, T. J. (2017). Mapping conceptions of wolf hunting onto an ecological worldview conceptual framework. In M. P. Mueller, D. J. Tippins, & A. J. Stewart (Eds.), Animals and science education (pp. 223–241). Springer.

- Sjöström, J. (2019). Didactic modelling for socio-ecojustice. Journal for Activist Science and Technology Education, 10(1), 45–56. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.33137/jaste.v10i1.32916

- Sjöström, J., & Eilks, I. (2018). Reconsidering different visions of scientific literacy and science education based on the concept of Bildung. In Y. J. Dori, Z. R. Mevarech, & D. R. Baker (Eds.), Cognition, metacognition, and culture in STEM education: Innovations in Science Education and Technology (Vol. 24, pp. 65–88). Springer.

- Sperling, E., & Bencze, J. L. (2015). Reimagining non-formal science education: A case of ecojustice-oriented citizenship education. Canadian Journal of Science, Mathematics and Technology Education, 15(3), 261–275. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14926156.2015.1062937

- Stake, R. E. (2000). Case studies. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 435–454). Sage.

- Stocklmayer, S. M., Rennie, L. J., & Gilbert, J. K. (2010). The roles of the formal and informal sectors in the provision of effective science education. Studies in Science Education, 46(1), 1–44. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03057260903562284

- Sutter, G. C. (2008). Promoting sustainability: Audience and curatorial perspectives on the human factor. Curator: The Museum Journal, 51(2), 187–202. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2151-6952.2008.tb00305.x

- Wellington, J. J. (1998). Interactive science centres and science education. Croner’s Heads of Science Bulletin (16).

- Westheimer, J., & Kahne, J. (2004). What kind of citizen? The politics of educating for democracy. American Educational Research Journal, 41(2), 237–269. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312041002237