ABSTRACT

The Seven Sister states of northeast India are characterized by diverse population with different ethnic backgrounds. Indigenous and fermented foods are an intrinsic part of diet of these ethnic tribes. It is the oldest and most economical methods for development of a diversity of aromas, flavors, and textures as well as for food preservation and biological enrichment by manipulation of different microbial populations. Wild fruits and vegetables have more nutritional value than cultivated fruits and contribute to sustainable food production and security. Fermented products are region-specific and have their own unique substrates and preparation methods. Soybeans, bamboo shoots, and locally available vegetables are commonly fermented by most tribes. Fermented alcoholic beverages prepared in this region are unique and bear deep attachment with socio-cultural lives of local people. These products serve as a source of income to many rural people, who prepare them at home and market them locally. Detailed studies on nutritive and medicinal value of these products can provide valuable information and would prove beneficial in guiding the use of these products on a wider scale. Furthermore, the ethnobotanical field exploration, conservation of indigenous knowledge, and proper documentation of wild edible bio-resources are suggested for sustaining the livelihood of local communities.

Introduction

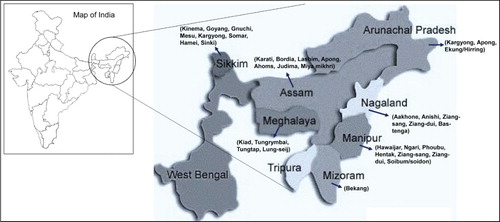

Northeast India, the eastern-most region of India, is connected with east India through a narrow corridor sandwiched between Nepal and Bangladesh. It mainly consists of the so-called Seven Sister states of India: Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, and Tripura. Northeast India constitutes about 8% of the total geographical area of India, having a population of approximately 40 million, which is about 3.1% of the total Indian population. Agriculture is the main occupation of the tribes, which practice ‘Jhum or shifting’ cultivation in which they grow cereals, vegetables, and fruits. The region is characterized by the presence of diverse physiography, hills, valleys, plains, and mountains. It has the richest reservoir of plant diversity in India and is one of the ‘biodiversity hotspots’ of the world, supporting about 50% of India’s biodiversity (Mao & Hynniewta Citation2000; Chatterjee et al. Citation2006). The region is also known as the Cradle of Flowering Plants and is a habitat of many botanical curiosities and rarities. The northeastern region has drawn attention for its high biodiversity and is a priority for leading conservation agencies across the globe. This area is inhabited largely by tribal people, who make up 75% of the population of the region (Agrahar-Murungkar & Subbulakshmi Citation2006).

Approximately 225 out of the 450 tribes of India reside in this region, representing different ethnic groups with distinct culture entities and rich traditional knowledge (Chatterjee et al. Citation2006; Mao et al. Citation2009). Some of the families that are unique to the world, such as Nepenthaceae, Liliaceae and Clethraceae, Ruppiaceae, Siphonodontaceae, Tetracentraceae, and others, can be found in this region. The region exhibits rich diversity in orchids, zingibers, bamboo, yams, rhododendrons, canes, and wild relatives of cultivated plants. The people of this region have a very rich reserve of traditional knowledge owing to their livelihood in the hilly terrains. These people possess great knowledge of the environment and depend on the forests, plants, and plant products for food and other purposes (Jaiswal Citation2010). Food plays a very important role in defining the identity of one ethnic group from the other. It is also noteworthy that there is still a very high demand among the urban-dwelling ethnic people for the wild edibles because of their traditional food habits and lifestyle (Asati & Yadav Citation2003; Medhi et al. Citation2013).

Very few outsiders have realized that northeast India is the center of a diverse food culture comprising fermented and non-fermented ethnic foods and alcoholic beverages (Sathe & Mandal Citation2016). Most of the people of this region bear their own methods of fermenting food materials for the purpose of preservation and taste enhancement, and they have been following these from time immemorial. Indigenous fermented foods are an intrinsic part of diet of the ethnic tribes in the Himalayan belt of India, being the oldest and most economic methods for development of a diversity of aromas, flavors, and textures, as well as food preservation and biological enrichment of food product by the manipulation of different microbial population (Sekar & Mariappan Citation2007). Ethnic fermented foods and alcoholic beverages and drinks have been consumed by the ethnic people of northeast India for more than 2500 years. All the fermented foods are region-specific and have unique substrates and preparation methods. Locally available materials such as milk, vegetable, bamboo, soybean, meat, fish, and cereal are commonly fermented (Das & Deka Citation2012; Tamang et al. Citation2012).

More than 250 different types of familiar and less-familiar ethnic fermented foods and alcoholic beverages are prepared and consumed by the different ethnic people of northeast India (). Daily per capita consumption of ethnic fermented foods and alcoholic beverages in Sikkim was 163.8 gm in the mid-2000s, representing 12.6% of total daily diet (Tamang et al. Citation2007). Ethnic fermented foods of northeast India are classified into fermented soybean and non-soybean legume foods, fermented vegetable (gundruk, sinki, anishi) and bamboo shoot foods (soibum, mesu), fermented cereal and pulse foods (kinema, bhatootu, marchu and chilra, tungrymbai), fermented and smoked fish products (ngari, hentak), preserved meat products, milk beverages (kadi, churpa and nudu), non-food mixed amylolytic starters, and alcoholic beverages (ghanti, jann, daru) (Tamang et al. Citation2012). The food-processing procedure makes use of various technologies to convert perishable, relatively bulky, and typically inedible raw materials into more useful palatable foods or potable beverages with increased self-life. Processing of food contributes to the food security by minimizing the wastage and loss of various ethnic food by increasing their availability and market value (Rolle & Satin Citation2002). Though these foods have great importance, detailed studies on the nutritive and medicinal value of these products can provide valuable information and indicate their potential use on a wider scale.

What is fermentation and why is it essential?

Fermentation is one of the oldest and most economical methods of preserving the quality and safety of foods, thereby enhancing the nutritional quality, flavor, and aroma of any product by increasing the amount of vitamins, fatty acids, amino acids, and protein solubility. The term fermentation is derived from the Latin word fervere, meaning ‘to boil.’ It refers to the action of yeast on extracts of fruit or malted grain during the production of alcoholic beverages. It may be defined as any process for the production of a product by the mass culture of microorganisms to break down complex compounds to produce a unique taste and aroma (Stanbury Citation1999). Fermentation process not only preserves foods, it also improves digestibility by breaking down proteins within foods and enables the production of organic acids, nutritional enrichment, reduction of endogenous toxins, and reduction in the duration of cooking (Sekar & Kandavel Citation2002). It enriched nutrients such as vitamins, amino acids, and fatty acids (Steinkraus Citation2004). Fermentation process also preserves the food, and produces beneficial enzymes, B-vitamins, Omega-3 fatty acids, and various strains of probiotics (Sathe & Mandal Citation2016).

Indigenous fermented food is prepared utilizing different substrates and non-pathogenic microorganisms as starter and processing culture to be sold at the local markets for local consumption. Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) play a major role in the production of most of the fermented foods and beverages (Mokoena et al. Citation2016). Many genera of the LAB have been isolated from different fermented foods and beverages available throughout the world. These genera include Alkalibacterium, Carnobacterium, Enterococcus, Lactobacillus, Lactococcus, Leuconostoc, Oenococcus, Pediococcus, Streptococcus, Tetragenococcus, Vagococcus, and Weissella (Axelsson et al. Citation2012; Holzapfel & Wood Citation2014; Tamang et al. Citation2016). Indigenous fermented foods have been prepared and consumed for thousands of years; they are strongly linked to culture and traditions, and they reveal the intellectual richness of indigenous people of the country in terms of their ability to prepare microbial products for varied purposes in addition to food and beverages (Sekar & Mariappan Citation2007). Fermentation also increases digestibility and exerts health-promoting benefits by improving the nutritional and functional properties of food. Breakdown of food proteins by the action of microbial or indigenous protease enzymes resulted in the increase of various bioactive peptides, leading to considerable increase in the biological properties of the food (Steinkraus Citation2002). Furthermore, the fermented food products are a good source of peptides and amino acids (Sathivel et al. Citation2003; Rajapakse et al. Citation2005; Majumdar et al. Citation2016). LAB isolated from various fermented foods produce organic acids and various bioactive compounds with antimicrobial potentials (Ananou et al. Citation2007; O’sullivan et al. Citation2010), which are generally responsible for the upkeep of quality and the deliciousness of the fermented foods (Mokoena et al. Citation2016). Fermentation may also assist in the destruction or detoxification of certain undesirable compounds, such as phytates, polyphenols, and tannins, which may be present in raw foods. Other health benefits include cholesterol control, anticancer effects, immunity, longevity, anti-hypertensive effect, and anti-diabetic effect (Sekar & Kandavel Citation2002). There are numerous traditional fermented food products abundantly available and widely consumed by the local populace of the northeastern region of India; these are discussed below.

Fermented foods of northeastern states of India

During the latter part of the twentieth century, around 3500 fermented foods and beverages which are broadly divided into about 250 groups have been available globally throughout the world (Campbell-Platt Citation1987). However, this list might have crossed 5000, in the present world which have been consumed by billions of people, as fermented foods and beverages (Ray et al. Citation2016; Tamang et al. Citation2016). On the Indian subcontinent, the fermented foods and beverages are a primary part of traditional heritage and culture. Even today indigenous fermented foods such as soybean products, bamboo shoots, fish, meat, vegetables, leaf, etc. contribute to the large proportion of the daily intake of the people of the northeastern states of India (Jeyaram et al. Citation2009). Their variety and mode of preparation vary from various communities of this region. The traditional knowledge of the ethnic women of this region plays an important role in the making of these fermented food and their further marketing within and outside of the region (Tamang et al. Citation2009). A few most common fermented foods of this region with high nutritional value is discussed below.

Types of fermented products

Food plays a very significant role in distinguishing one ethnic group’s identification (Somishon & Thahira Banu Citation2013). Fermented foods and its products are prepared and consumed worldwide. These traditional fermented food products consumed by the local people of the northeastern states of India are rich in various nutrients such as protein, vitamins, carbohydrates, fat, and minerals (Tamang et al. Citation2012). Among all the ethnic fermented foods and alcoholic beverages consumed by the different ethnic tribal people of north-east states of India, most of them are region-specific and have their distinctive preparation procedure utilizing various specific substrates (Das & Deka Citation2012; Tamang et al. Citation2012; Somishon & Thahira Banu Citation2013). Locally available materials such as milk, vegetable, bamboo, soybean, meat, fish, and cereal are commonly fermented (Das & Deka Citation2012; Tamang et al. Citation2012). The climatic condition of the region (temperate, sub-tropical, and tropical climate) also plays an important role in the type of fermented food produced and available in the north-east states of India (Somishon & Thahira Banu Citation2013). These fermented foods have been categorized into subcategories according to their nutritional composition and are discussed subsequently in this review ().

Table 1. Types of fermented food products and their nutritional composition and nutraceutical potential.

Fermented food made up of vegetables

A number of fermented food products have been prepared and consumed by the local tribes of the northeastern states of India, and some of them are discussed below. Gundruk is a common non-salted dried fermented leafy vegetable food of the Gorkha tribes of northeastern states of India. It is commonly prepared during winter season from the leaves of cauliflowers (Brasicca oleracea), mustard (Brasicca juncea), radish (Raphanus sativus), rayo-sag (Brasicca rapa), and some other locally grown vegetables (Tamang & Tamang Citation2009a). Sinki is a non-salted fermented radish tap root (Raphanus sativus L.), consumed by the Nepalis tribe in Darjeeling, Sikkim, and Nepal. It is prepared during the months of winter when weather is least humid and there is ample supply of this vegetable (Tamang & Sarkar Citation1993; Sekar & Mariappan Citation2007). It is said to be a good appetizer and is used as a remedy for indigestion (Tamang & Sarkar Citation1993). Ziang-sang/ Ziang-dui is a fermented leafy vegetable product common to the states of Manipur and Nagaland. It is produced mainly by the Naga women and sold in the local markets (Tamang & Tamang Citation2009a). Fermented extract ziang dui is used as a condiment. The Sherpa tribe belonging to the state of Sikkim and hills of Darjeeling prepare a type of fermented product from leaves of the wild plant maganesaag (Cardamine macrophylla Wild), which is called goyang in the local language (Tamang & Tamang Citation2009a). Khalpi is a cucumber product of the state of Sikkim and Darjeeling hills. Anishi is another fermented food made from the leaves of edible yam (Colocasia sp.). It is used as a condiment and is usually cooked with dry meat, especially pork (Mao & Odyuo Citation2007).

Fermented food made up of bamboo shoots

In India mostly in the northeastern states, different varieties of fermented foods and beverages out of the bamboo shoots have been traditionally prepared and consumed (Thakur et al. Citation2016). These bamboo shoots are fermented by a number of LAB including Enterococcus durans, Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus brevis, Lactobacillus casei, Lactobacillus coryniformis, Lactobacillus fermentum, Leuconostoc mesenteroides, Leuconostocfallax, Lactococcuslactis, Streptococcus lactis, and Tetragenococcus halophilus etc. (Thakur et al. Citation2016). These fermented bamboo shoots products are rich in bioactive nutrients and possess functional probiotic properties as well as B-vitamin supplier to human body (Jeyaram et al. Citation2010; Thakur et al. Citation2016). A number of fermented foods made up of bamboo shoots are described below.

Soibum are the fermented bamboo shoot products and are indigenous foods of the state of Manipur. They are consumed as an indispensable part of the Manipuri diet and are part of the social customs of the people. Soibum are produced exclusively from succulent bamboo shoots of the species Dendrocalamus hamiltonii, Dendrocalamus sikkimensis, Dendrocalamus giganteus, Melocana bambusoide, Bambusa tulda, and Bambusa balcona (Bhatt et al. Citation2003; Jeyaram et al. Citation2009). When the apical meristems of succulent bamboo shoots are fermented, the product is known as soidon. The species used are Teinostachyum wightii, B. tulda, Dendrocalamus giganteus, and M. bambusoide (Jeyaram et al. Citation2009; Tamang & Tamang Citation2009a). Mesu is another fermented bamboo shoot product indigenous to the people of Himalayan regions of Darjeeling hills and Sikkim. The species of bamboo used are the locally available choya bans (D. hamiltonii Nees and Arnott), bhalu bans (D. sikkimensis Gamble), and karati bans (B. tulda Roxb) (Sekar & Mariappan Citation2007; Tamang & Tamang Citation2009a). Lung-seij, another ethnic fermented bamboo shoot product, belongs to the state of Meghalaya and is produced mainly by the Khasi tribe. It is prepared from D. hamiltonii species of bamboo available locally in Meghalaya (Tamang & Tamang Citation2009a).

Ekung/Hirring is another ethnic fermented bamboo shoot product of the state of Arunachal Pradesh. It is referred to as ekung by the Nyishing tribe and hirring by the Apatani tribe of Arunachal Pradesh. It is prepared from young bamboo shoot sprouts (Tamang & Tamang Citation2009a, Citation2009b). Eup, the word derived from the Nishi dialect, is a dry fermented bamboo tender shoot product of Arunachal Pradesh (Tamang Citation2010). Miya mikhri is produced by the Dimasa tribe of Assam from the bamboo shoots cut into small pieces, wrapped in banana leaf, and kept inside an earthen pot. Miya mikhri can be taken as a pickle or even mixed with curry (Chakrabarty et al. Citation2009).

Fermented foods made up of soybean

Soybean, in the Nepali language called ‘bhatmas’, is a most common raw material for traditional preparation of various fermented and non-fermented foods in the Eastern Himalayan regions of Nepal, India, and Bhutan (Tamang Citation2015). There are a number of fermented foods prepared by soybean seeds or paste by the local people of the northeastern states of India. Some of these food products are described below.

Kinema is a traditional fermented soybean food prepared by the people of Nepal in the Eastern Himalayas. It is a whole-soybean fermented food which is very sticky with gray tan color, and is flavorsome (Tamang Citation2015). Kinema production is a source of income generation for many families in the Eastern Himalayas. Kinema is sold by rural women in all local periodical markets in eastern Nepal, Darjeeling hills, Sikkim, and southern parts of Bhutan. Kinema is eaten as curry with steamed rice. Several species of Bacillus have been isolated from kinema including Bacillus subtilis, Bacillus licheniformis, Bacillus cereus, Bacillus circulans, Bacillus thuringiensis, and Bacillus sphaericus (Sarkar et al. Citation2002; Tamang Citation2015).

Hawaijar is an indigenous traditional fermented soybean product of Manipur with a characteristics flavor and stickiness; it has been consumed as a regular food in every household (Premarani & Chhetry Citation2011). Hawaijar is known for its unique organoleptic properties. It plays an economical, social, and cultural role in the culture and tradition of the Manipur state of India. Hawaijar making provides income to a number of rural masses in Manipur (Premarani & Chhetry Citation2011; Das & Deka Citation2012). It is consumed by the local people of Manipur as a low-cost source of high protein food (Devi & Kumar Citation2012). Besides, there are reports on its medicinal potential in terms of its anticancer, anti-osteoporosis, and hypocholesterolemic effects (Somishon & Thahira Banu Citation2013). A special delicacy of the Manipuris called chagempomba is prepared using hawaijar, rice, and other vegetables. Kinema is a sticky fermented soybean food with ammonical flavor produced exclusively by Nepali women belonging to Limboo and Rai castes of Sikkim, Darjeeling hills, east Nepal, and Bhutan (Tamang Citation2001). It serves as a major source of protein in the diet of the people of this region. Tungrymbai, an ethnic fermented soybean food of Meghalaya, is prepared by Khasi women (Agrahar-Murungkar & Subbulakshmi Citation2006). Aakhone, or Axone, is an ethnic sticky fermented soybean food of Nagaland. Cooked soybeans are wrapped in leaves of banana or Phrynium pubinerve or Macaranga indica and are kept above a fireplace to ferment for 5–7 days (Mao & Odyuo Citation2007).

Bekang is a fermented soybean food of Mizoram. Small soybeans are soaked for 10–12 h, boiled, and wrapped in leaves of Calliparpa aroria or leaves of Phrynium sp., then kept inside a bamboo basket. It is then kept near the earthen oven and fermented for 3–4 days. Sticky beans with ammoniacal flavor are produced to get bekang. It is consumed as curry with rice. Peruyyan is an ethnic fermented soybean food prepared by Apatani women in Arunachal Pradesh. It is prepared from the cooked bean kept in a bamboo basket lined with ginger leaves, locally referred to as taki yannii. It is consumed as a side dish with rice.

Fermented foods made up of rice, legumes, and cereal

Maseura, or masyaura, is prepared from black gram by the Gorkha. It is a cone-shaped hollow, brittle, and friable product. Maseura is similar to North Indian wari or dal bodi and South Indian sandige (Chettri & Tamang Citation2008). Maseura can be stored in a dry container at room temperature for a year or more. Selroti is a popular fermented rice product, of the Gorkha/ethnic Nepali, which is ring shaped, spongy, pretzel-like, and deep-fried food (Yonzan & Tamang Citation2009).

Due to the large production of rice in the Indian subcontinent, many varieties of fermented foods and beverages made up of rice and the principal component are a regular practice since ancient days (Roy et al. Citation2004; Ray et al. Citation2016). The fermented-rice-based products play a fundamental role in the social, rituals, and festivals around the subcontinent. Most common rice-based fermented food available in India are idli, dosa, dhokla, uttapam, selroti, babru, ambeli, vada, sez, etc. (Ray et al. Citation2016). Many diverse rice-based food items locally known as ‘ki kpu’ prepared by traditional procedures are available in the northeastern states of India including Meghalaya (Umdor et al. Citation2016). The commonly available traditional rice cakes are putharo, pusyep, pumaloi, pusaw, etc. (Umdor et al. Citation2016). Another recipe was also known as kanjika: boiled millet or barley or boiled rice was used as a base material and to them different plants and spices were added into the fermented medium (Roy Citation1997).

Fermented food made up of milk

A number of fermented milk food types have been prepared by the local people of the northeastern states of India for personal consumption and economy purposes, some of them are discussed subsequently. Dahi (curd) is a popular fermented milk product for direct consumption as well as for the preparation of various ethnic milk products such as gheu, mohi, and chhurpi (Tamang Citation2010). It is consumed directly as a refreshing non-alcoholic beverage. Two types, hard chhurpi and soft chhurpi, are popular among the ethnic people of Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh. Hard chhurpi is prepared from yak milk at high-altitude mountains (2100–4500 m) and has characteristics of gumminess and chewiness. Soft chhurpi is a cheese-like fermented milk product that is slightly sour in taste (Tamang et al. Citation2000). Chhu, or sheden, is an ethnic fermented milk product of the Bhutia, Khamba, Lepcha, Memba, Monpa, Sherdukpen, and the Tibetan living in northeast India. It is a strong-flavored traditional cheese-like product prepared from yak milk (Dewan & Tamang Citation2006). Somar, a soft paste, brownish with strong flavor, is an ethnic fermented milk (yak/cow) product of Sikkim traditionally consumed by the Sherpa (Tamang Citation2010). Philu is an ethnic fermented, cream-like dairy product, with an inconsistent semi-solid texture; it is consumed by various tribes of northeast India (Tamang Citation2010). The soft mass, philu, is scraped off and stored in a dry place for consumption.

Fermented food made of fish or meat

Apart from the fermentation of various fruits, vegetables, and pulses, a number of fish and meat products have been fermented for their increased nutritional value and long-term edibility. Among all the types of fermented foods, the meat and meat products play a vital role in the human food system (Ahmad & Srivastava Citation2007). The fermentation of meat and meat products are done by the process of preservation using natural microbial cultures and preservatives. In the states of northeast India, the meat is salted, dried, and kept for long time at very low temperature (Tamang Citation2013). These food products are described below.

The fermented fish product ngari is prepared from dried Puntius sophore fish, and it forms an intrinsic part of the diet of the people in Manipur (Jeyaram et al. Citation2009). Hentak is a traditional fermented fish paste prepared in the state of Manipur (Sarojnalini & Singh Citation1988). Tungtap is a fermented fish paste prepared from P. sophore found in Meghalaya. The process of fermentation enhances the palatability of the small fishes by softening the bones and improving the flavor and texture of the meat. Gnuchi is a smoked and dried fish product commonly eaten by the Lepcha community of Sikkim. The fishes used for its preparation include Schizothorax richardsonii, Labeo dero, Acrossocheilus spp., and Channa sp. Traditionally smoked fish product is called suka ko maacha by the Gorkha. The hill river fish ‘dothay asala’ (Schizothorax richardsoni) and ‘chuchay asala’ (Schizothorax progastus) are air-dried by a specific method and consumed directly (Thapa et al. Citation2006). Sidra is a sun-dried fish product of Puntius sarana fish. Sidra pickle is a popular cuisine (Thapa et al. Citation2006). Sukuti is also a very popular sun-dried Harpodon nehereus fish product cuisine of the Gorkha (Thapa et al. Citation2006). Sukuti is consumed as pickle, soup, or curry. Karati, bordia, and lashim are sun dried and salted fish products of Assam. Karati is prepared from Gudusia chapra; bordia is prepared from Pseudeutropius atherinoides; and lashim is prepared from Cirrhinus reba (Thapa et al. Citation2007).

Shidal is a salt-free, solid, semi-fermented fish product which is commonly consumed in the northeastern states of India. Shidal is prepared from a small sized fish mainly Puntius sp. and also known as seedal, seepa, hidal, and shidal in different states such as Assam, Tripura, Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland whereas it is called Ngari in Manipur (Ahmed et al. Citation2016). It is prepared by a complex procedure including semi-drying of Puntius sp. in the sunlight, keeping them in vats or earthen pots for fermentation process for around 4–6 months in which the final product has a semi-solid appearance. A chutney or sauce-like recipe, locally called shidal bhorta, is prepared as a side dish for rice or bread (Ahmed et al. Citation2016).

Kargyong is a sausage-like meat (yak/beef/pork) product of Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh (Rai et al. Citation2009). Kargyong is eaten after boiling for 10–15 min, sliced, and made into curry or fried sausage. Satchu is an ethnic dried meat (beef/yak/pork) and is consumed by the Tibetan, the Bhutia, the Lepcha, the Sherdukpen, and the Khamba (Rai et al. Citation2009). Suka ko masu is a dried or smoked meat product prepared from buffalo meat or chevon (goat meat) (Rai et al. Citation2009).

Fermented foods used as beverages

Hamei is a natural starter (dry, round-to-flattened, solid ball-like mixed dough) similar to Ragi of Indonesia, Budob of the Philippines, Chu of China, Naruk of Korea, and Marcha of Darjeeling hills and Sikkim; it has been traditionally used for the preparation of rice wine, Atingba in Manipur (Tamang et al. Citation2007; Jeyaram et al. Citation2008). Marcha is a dry flattened to round, solid ball-like mixed amylolytic starter, used to ferment starchy materials into a number of fermented beverages and alcoholic drinks confined to the Gorkha (Tamang et al. Citation1996). For preparation of Atingba, Hamei is used by crushing the flat cake then mixing the powder with cooked, cooled glutinous rice (5 cakes/10 kg). The most popular fermented finger millets-based mild alcoholic beverage with a sweet-sour and acidic taste is kodo ko jaanr, or chyang, or chee, prepared and consumed by the Gorkha, the Bhutia, the Lepcha, the Monpa, and many ethnic groups of northeast India. It is an integral part of dietary culture and religious beliefs among the ethnic people in the Sikkim (Tamang et al. Citation1996; Sekar & Mariappan Citation2007). Zutho or zhuchu is an ethnic alcoholic beverage of the Mao Naga prepared from rice (Mao Citation1998). Bhaati jaanr is an ethnic fermented rice beverage, consumed as a staple food beverage by the Gorkha in northeast India. Bhaati jaanr is made into a thick paste by stirring the fermented mass with the help of a hand-driven wooden or bamboo stirrer (Tamang & Thapa Citation2006).

Kiad is popular local liquor prepared by the Jaintia tribe (also known as Pnar or Synteng) of the Jaintia hills of the state of Meghalaya. It plays an important role in Jaintia socio-cultural life and accompanies every religious festival and ceremony (Samati & Begum Citation2007; Jaiswal Citation2010). Bas-tenga, which means ‘sour bamboo,’ is the fermented form of bamboo shoots and produced by the Nagas of Nagaland (Mao & Odyuo Citation2007). Apong is an alcoholic beverage prepared in the state of Arunachal Pradesh and is familiar to almost all the tribes of the state (Tiwari & Mahanta Citation2007). The Ahoms of Assam prepare a kind of rice beer, which they refer to locally as xaj-pani. It is the most important beverage for use in religious rites and rituals practiced among the Ahoms (Saikia et al. Citation2007). Another type of rice beer prepared by the Dimasa tribe of Assam is judima (Chakrabarty et al. Citation2009).

Nutraceutical potential and bioactive secondary metabolites of the fermented foods

All types of fresh foods such as fruits, vegetables, cereals, fish, and meat products undergo a number of beneficial biochemical changes, nutritional enrichments, and nutraceutical enrichments during the fermentation process by the action of a number of beneficial microorganism and the enzymes and secondary metabolites produced by them (Vijayendra & Halami Citation2015). The process of fermentation of food increases the shelf-life of the food with the production of organoleptic properties with increased nutritional and nutraceutical potential (Parvez et al. Citation2006). The process of fermentation of foods helps to increase a number of secondary metabolites and bioactive compounds in the food that provide it antimicrobial and antioxidant potential to the food (Vijayendra & Halami Citation2015).

A number of fermented foods and beverages that are abundantly consumed by the local tribes in and around the entire northeastern region of India possess a number of health benefits as well as nutritional and nutraceutical potential. They provide increased nutrition such as proteins, vitamins, added minerals and phytochemicals, phytosterols, and dietary fibers to the consumer () (Vijayendra & Halami Citation2015). Kinema, a fermented product of the northeastern region, showed increased level of total content of amino acids, riboflavin, and niacin, which possess cholesterol-lowering effects (Sarkar & Tamang Citation1995; Sarkar et al. Citation1996, Citation1998; Tamang & Nikkuni Citation1998). Kinema is rich in linoleic acid (Sarkar et al. Citation1996) and contains all essential amino acids (Sarkar et al. Citation1997). Kinema has antioxidant activities (Tamang et al. Citation2009). Hentak is a traditional fermented fish paste prepared in the state of Manipur. It is sometimes given to women in the final stages of their pregnancy (confinement) or patients recovering from sickness or injury (Sarojnalini & Singh Citation1988). Similarly, Chyang, a fermented finger millet, is given to the women post-delivery to increase their internal strength (Thapa & Tamang Citation2004). Sinki, a radish tap-root fermented product, is used by the local tribes as a cure against diarrhea and stomach disorders (Tamang Citation2010). Gundruk improves the milk efficiency in new mothers (Tamang & Tamang Citation2010). Gundruk soup is eaten as a good appetizer and possesses a higher quantity of ascorbic acid, lactic acid, and carotene with anticancer properties (Tamang et al. Citation2005). The fermented bamboo shoots, which are rich in phenolic compounds and tannin, possess antioxidant, anticancer, and anti-aging properties (Tamang & Tamang Citation2009a). Beside this, the fermented food products are a rich source of vitamins, minerals, essential amino acids, and fatty acids that are essential for the growth and development of human health.

Figure 2. Chemical structure of selected bioactive compounds from various traditional fermented foods found in northeast states of India.

Fermented rice bran has been reported to possess anticancer properties against various types of cancers, including colon, stomach, and bladder (Phutthaphadoong et al. Citation2009). The fermented rice beer is rich in a number of bioactive compounds, such as maltooligosaccharides such as maltotetrose, maltotriose, and maltose, which are low in calories, inhibit the growth of intestinal pathogenic microorganisms, and are very nutritious for infants and the elderly (Ghosh et al. Citation2015). Apart from these, due to the process of fermentation, a number of pyranose derivatives such as 1,2,3,6-tetra-O-acetyl-4-O-formyl-D-glucopyranose, b-D-mannopyranose pentaacetate, 2,3,4,5-tetra-O-acetyl-1-deoxy-b-D-glucopyranose, and b-D-galactopyranose pentaacetate, along with phenolic and flavanol group of compounds are also accumulated in the rice beer. These provide elevated antioxidant, antimutagenic, cardiovascular, free radical scavenging, and immune-stimulatory activities (Das et al. Citation2014; Ghosh et al. Citation2015; Ray et al. Citation2016).

Traditional wild foods of northeast India and their potential medicinal uses

The use of wild plants as food is an essential part of the culture and tradition of many aboriginal communities around the world (Konsam et al. Citation2016). A large section of the rural population meets their dietary requirement by consuming various wild plants and animal resources available around them (Konsam et al. Citation2016). Wild edible plants (WEPs) constitute an indispensable constituent in the disparity of diet and bring household food security of many traditional communities found in different parts of the world (Schippmann et al. Citation2002).

The northeast region of India is biodiversity hotspot with a number of mountains and rich floral resources where many ethnic communities live. WEPs are extensively consumed by the local people in this region. These WEPs play a vital and significant role for the sustenance of the ethnic communities dwelling in this region and also these edible plants are a source of bread and butter for them (Konsam et al. Citation2016). However, study on these WEPs received very little attention and many of them are largely ignored and remained unexplored.

WEPs are species that are neither cultivated nor domesticated, but available from their natural habitat and used as sources of food and nutrition in the population (, ). Various studies have found WEPs as potential sources of nutrition, and in many cases they are more nutritious than conventionally eaten crops (Grivetti & Ogle Citation2000). Besides the use of wild fruits as a source of food and nutrition, they are also utilized as a coping strategy during times of food scarcity, particularly in developing countries where food insecurity is more acute. Wild edible fruits that are obtained from these wild plants are important constituents of the biodiversity and they are highly exploited for the livelihood of the tribal people of northeastern India, especially Nagaland. Wild fruits generally help in bringing variety in the otherwise bland diet of the tribal people along with providing a nutritional balance to the tribal food habit. Some of the main fruits that are generally used by the people of Nagaland and the tribes of northeastern India are discussed here. These fruits are taken for their nutritional as well as medicinal and economic values.

Table 2. Plants with wild edible fruits and vegetables of northeastern states of India.

Some of the most common fruits that are used by the tribal people for their medicinal effects against various diseases such as stomach disorders, intestinal worms, cough, cold, and fever are elaborated below (). Aegle marmelos, commonly known as bael, is generally eaten raw or ripe. Its juice is made into a refreshing drink. On the other hand, the unripe bael fruits are effective against diseases such as chronic diarrhea and dysentery. Besides, the unripe green fruit is sliced into small pieces, dried in the sun, and then made into powder for their potential application as traditional medicine against constipation (Sharma et al. Citation2007). The ripened fruit of Rhus javanica is an effective cure for diarrhea and dysentery. These are some of the wild fruits that are much used by the tribal people for indigenous methods of cure for diseases. Eryngium foetidium is widely used to impart flavor to traditional curries and meat preparation. In addition, the decoction of the fruits is used for curing dysentery. The juice obtained from the leaves is applied on the forehead for lowering the fever, as it has a cooling effect. Another plant used as a cure for diarrhea and dysentery is Eurya acuminate. This is also widely eaten as a vegetable. It also has an emetic and purgative effect, which makes it a popular traditional medicine. Myrica nagi bark is acrid, pungent, and bitter in taste and has applications in the remedy for anemia, asthma, bronchitis, cough, chronic dysentery, fever, liver complaints, piles, sores, ulcers, and urinary discharges (Panthari et al. Citation2012). On the other hand, oil extracted from Myrica esculenta is used as a tonic and is effective for the treatment of various diseases such as earache, headache, diarrhea, and paralysis. These two plants are widely used among the tribal people of northeastern India and hence they face a threat of extinction (Panthari et al. Citation2012). Benincasa hispida is also used by the tribal people as a diuretic tonic. The drug is traditionally prepared by extracting juice from the fruits (Rout et al. Citation2012).

Table 3. Uses of different plants as fruit and for other medicinal purposes.

Houttuynia cordata, locally known as ‘Mosandri,’ is used by the tribal people as a regular food. The leaves are boiled and the juice is taken as a drink for treating intestinal worms (Roy et al. Citation2012). Alpinia nigra is another plant that is widely used by the tribal people for its anti-helminthic properties. The shoot of the plant as well as a part of the rhizome is generally used by the indigenous tribal people of Tripura as a vegetable. Medicinally, the aqueous juice of the shoots is used for treating intestinal worms and parasites (Roy et al. Citation2012). Adhatoda vasica is generally used by the tribal people for treating intestinal worms (Sivanathan Citation2013). Another plant considered more or less similar to A. vasica in its medicinal properties is Phlogacanthus thyrsiflorus. Fruits and leaves of this plant are burnt and then used as a special treatment for fever. Curry prepared from the aerial portion is given orally with rice, once daily until cured (Kalita & Kalita Citation2014). Fruits and leaves are used by the Karbi tribes of Assam in a similar way (i.e. by burning) and used as a special treatment for fever. The flowers, on the other hand, have proven to be effective against pox, skin diseases like sores and scabies (Phurailatpam et al. Citation2014). Another plant with a decent medicinal value, Antidesma bunius, is used by the people of Mizoram. The fruits of this particular plant are effective against gastric intestinal problems. Apart from that, the matured leaves of this plant are used as an antidote to snake bites, and the young leaves are boiled and used against the disease, syphilis, and various skin disorders (Hazarika et al. Citation2012).

Among the common wild herbs and vegetables are wild banana, wild brinjal, and tomato. There are plants or plant parts like yam, mustard leaf, and wild cabbage that are preserved for lean and thin periods by drying. Another wild plant profusely found in the forests of Nagaland is bamboo (Jamir et al. Citation2010). Its shoot is preserved by an indigenous method and is kept in an airtight container with water for further use. Bamboo shoots are among the most commonly eaten food items, after meat. In Nagaland the wild fruits are in great demand and hence are sold for higher prices than fresh fruits. Some families depend entirely on wild fruits, wild vegetables, and wild honey for their income and livelihood (Jamir Citation1995). Besides these, various edible algae are also part of the traditional food system of the tribal people of the northeastern states of India (Das Citation2016). The study of WEPs is important not only for identifying potential sources of alternative food, but also for selecting promising types for domestication.

Conclusion

Traditional foods, wild fruits, and fermented fruits and vegetables contain a diverse group of prebiotic compounds that attract and stimulate the growth of probiotics. Basic understanding about the relationship between food, beneficial microorganisms, and health of the human being is important to improve the quality of food as well as prevention of several diseases. Furthermore, concern and awareness among the consumers about the type and quality and the raw materials used for preparation of various types of fermented food products and their safety is continually increasing. Although there are a number of challenges in the processing and production of various fermented food products, it is clear that the traditional knowledge of the natives of the northeastern states of India in preparation of different types of fermented food items offers an enormous opportunity for the development of various food industries related to fermented products, quality improvements, and enhanced wider-scale marketing.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the local people of the northeastern states of India for giving us information on various indigenous tribal foods and their beneficial effects. This study was supported by the Agricultural Research Center funded by the Ministry of Food, Forestry, and Fisheries, Republic of Korea.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Agrahar-Murungkar D, Subbulakshmi G. 2006. Preparation techniques and nutritive value of fermented foods from the Khasi tribes of Meghalaya. Ecol Food Nutr. 45:27–38. doi: 10.1080/03670240500408336

- Ahmad S, Srivastava PK. 2007. Quality and shelf life evaluation of fermented sausages of buffalo meat with different levels of heart and fat. Meat Sci. 75:603–609. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2006.09.008

- Ahmed S, Dora KC, Sarkar S, Chowdhury S, Ganguly S. 2016. Production process, nutritional composition, microbiology and quality issues of shidal, a traditional fermented indigenous fish product: A review. Int J Sci, Environ Technol. 5:589–598.

- Ananou S, Maqueda M, Martinez-Bueno M, Valdivia E. 2007. Biopreservation, an ecological approach to improve the safety and shelf-life of foods. In: Mendez-Vilas A, editor. Communicating current research and education topics and trends in applied microbiology. Madrid: FORMATEX; p. 475–486.

- Asati BS, Yadav DS. 2003. Diversity of horticultural crops in North Eastern Region. ENVIS Bulletin: Himalayan Ecol. 12:1–10.

- Axelsson L, Rud I, Naterstad K, Blom H, Renckens B, Boekhorst J, Kleerebezem M, van Hijum S, Siezen RJ. 2012. Genome sequence of the naturally plasmid-free Lactobacillus plantarum strain NC8 (CCUG61730). J Bacteriol. 194:2391–2392. doi: 10.1128/JB.00141-12

- Bareh HM. 2001. Encylopaedia of north-east India (Volume VI). New Delhi: Mittal Publications.

- Bhatt BP, Singha LB, Singh K, Sachan MS. 2003. Some commercial edible bamboo species of North East India: production, indigenous uses, cost-benefit and management strategies. Bamboo Sci Cult. 17:4–20.

- Campbell-Platt G. 1987. Fermented foods of the world: a dictionary and guide. London: Butterworths.

- Chakrabarty J. 2011. Microbiological and nutritional analysis of some fermented foods consumed by different tribes of North Cachar Hills District of Assam [Ph.D. thesis]. Food Microbiology Laboratory, Sikkim Government College, Gangtok, India.

- Chakrabarty J, Sharma GD, Tamang JP. 2009. Substrate utilization in traditional fermentation technology practiced by tribes of North Cachar Hills District of Assam. Assam University J Sci Technol: Biol Sci. 4:66–72.

- Chakraborty S, Chaturvedi HP. 2014. Some wild edible fruits of Tripura – a survey. Indian J Appl Res. 4:566–569.

- Changkija S. 1999. Folk medicinal plants of the Nagas in India. Asian Folklore Stud. 58:205–230. doi: 10.2307/1178894

- Chatterjee S, Saikia A, Dutta P, Ghosh D, Pangging G, Goswami AK. 2006. Background paper on biodiversity significance of North East India for the study on natural resources, water and environment nexus for development and growth in North Eastern India. New Delhi: WWF-India.

- Chettri R, Tamang JP. 2008. Microbiological evaluation of maseura, an ethnic fermented legume-based condiment of Sikkim. J Hill Res. 21:1–7.

- Chettri R, Tamang JP. 2015. Bacillus species isolated from tungrymbai and bekang, naturally fermented soybean foods of India. Int J Food Microbiol. 197:72–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2014.12.021

- Das AJ, Deka C. 2012. Fermented foods and beverages of Northeast India. Int Food Res J. 19:377–392.

- Das SK. 2016. Dietary use of algae among tribal of North-East India: special reference to the Monpa tribe of Arunachal Pradesh. Indian J Trad Know. 15:509–513.

- Das AK, Dutta BK, Sharma GD. 2008. Medicinal plants used by different tribes of Cachar district, Assam. Indian J Trad Know. 7:446–454.

- Das AJ, Khawas P, Miyaji T, Deka SC. 2014. HPLC and GC-MS analyses of organic acids, carbohydrates, amino acids and volatile aromatic compounds in some varieties of rice beer from northeast India. J Institute Brewing. 120:244–252. doi: 10.1002/jib.134

- Deb CR, Jamir NS, Ozukum S. 2013. A study on the survey and documentation of underutilized crops of three districts of Nagaland, India. J Global Biosci. 2:67–70.

- Devi P, Kumar SP. 2012. Traditional ethnic and fermented foods of different tribes of Manipur. Indian J Trad Know. 11: 70–77.

- Dewan S. 2002. Microbiological evaluation of indigenous fermented milk products of the Sikkim Himalayas. [Ph.D. Thesis]. Food Microbiology Laboratory, Sikkim Government College (North Bengal University), Gangtok, India, p. 162.

- Dewan S, Tamang JP. 2006. Microbial and analytical characterization of Chhu, a traditional fermented milk product of the Sikkim Himalayas. J Scientific Industrial Res. 65:747–752.

- Dey S, Jamir NS, Gogoi R, Chaturvedi SK, Jakha HY, Kikon ZP. 2014. Musa nagalandiana sp. nov. (Musaceae) from Nagaland, Northeast India. Nordic J Bot. 32:584–588. doi: 10.1111/njb.00516

- Dutta B. 2015. Food and medicinal values of certain species of dioscorea with special reference to Assam. J Pharmaco Phytochem. 3:15–18.

- Ghosh K, Ray M, Adak A, Dey P, Halder SK, Das A, Jana A, Parua (Mondal) S, Das Mohapatra PK, Pati BR, Mondal KC. 2015. Microbial, saccharifying and antioxidant properties of an Indian rice based fermented beverage. Food Chem. 168:196–202. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.07.042

- Gogoi B, Zaman K. 2013. Phytochemical constituents of some medicinal plant species used in recipe during ‘BohagBihu’ in Assam. J Pharmacog Phytochem. 2:30–40.

- Grivetti LE, Ogle BM. 2000. Value of traditional foods in meeting macro- and micronutrient needs: the wild plant connection. Nutrition Res Rev. 13:31–46. doi: 10.1079/095442200108728990

- Hazarika TK, Lalramchuana, Nautiyal BP. 2012. Studies on wild edible fruits of Mizoram, India used as ethno-medicine. Genetic Resour Crop Evol. 59:1767–1776. doi: 10.1007/s10722-012-9799-5

- Holzapfel WH, Wood BJB. 2014. Lactic acid bacteria: biodiversity and taxonomy. New York (NY): Wiley-Blackwell; p. 632. doi: 10.1002/9781118655252

- Hore DK. 2001. North East India – a hot-spot for agrodiversity. Summer School on Agriculture for Hills and Mountain Ecosystem; p. 361–362.

- Jaiswal V. 2010. Culture and ethnobotany of Jaintia tribal community of Meghalaya, Northeast India – a mini review. Indian J Trad Knowl. 9:38–44.

- Jamir NS. 1995. Study of the wild edible fruits in Nagaland State, India. Non-Timber Forest Prod. 2:79–82.

- Jamir NS. 1997. Ethnobiology of Naga tribes in Nagaland: 1. Medicinalherbs. Ethnobotany. 9:101–104.

- Jamir NS, Jungdan, Madhabi S. 2008. Traditional knowledge of medicinal plants used by the Yimchunger – Naga tribes in Nagaland. Pleione. 2:223–228.

- Jamir NS, Rao RR. 1990. Fifty new interesting medicinal plants used by the Zeliang of Nagaland (India). Ethnobotany. 2:11–18.

- Jamir NS, Takatemjen, Limasemba. 2010. Traditional knowledge of Lotha Naga tribe in Wokha District, Nagaland. Indian J Trad Knowl. 9:45–48.

- Jeyaram K, Romi W, Singh TA, Devi AR, Devi SS. 2010. Bacterial species associated with traditional starter cultures used for fermented bamboo shoot production in Manipur state of India. Int J Food Microbiol. 143:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.07.008

- Jeyaram K, Singh TA, Romi W, Devi AR, Singh WM, Dayanidhi H, Singh NR, Tamang JP. 2009. Traditional fermented foods of Manipur. Indian J Trad Know. 8:115–121.

- Jeyaram K, Singh WM, Premarani T, Ranjita Devi A, Chanu KS, Talukdar NC, Singh MR. 2008. Molecular identification of dominant microflora associated with ‘Hawaijar’ – a traditional fermented soybean (Glycinemax (L.)) food of Manipur, India. Int J Food Microbiol. 122:259–268. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.12.026

- Kala CP, Farooquee NA, Dhar U. 2005. Traditional uses and conservation of Timur (Zanthoxylum armatum) through social institutions in Uttaranchal Himalaya, India. Conservation Soc. 3:224–230.

- Kalita N, Kalita MC. 2014. Ethnomedicinal plants of Assam, India, as an alternative source of future medicine for treatment of Pneumonia. Int Res J Biol Sci. 3:76–82.

- Kayang H. 2007. Tribal knowledge on wild edible plants of Meghalaya, Northeast India. Indian J Trad Know. 6:177–181.

- Khomdram S, Arambam S, Devi GS. 2014. Nutritional profiling of two underutilized wild edible fruits Elaeagnuspyriformis and Spondiaspinnata. Annal Agri Res. 35:129–135.

- Konsam S, Thongam B, Handique AK. 2016. Assessment of wild leafy vegetables traditionally consumed by the ethnic communities of Manipur, northeast India. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 12:15. doi: 10.1186/s13002-016-0080-4

- Laloo CR, Kharlukhi L, Jeeva S, Mishra BP. 2006. Status of medicinal plants in the disturbed and the undisturbed sacred forests of Meghalaya, Northeast India: population structure and regeneration efficacy of some important species. Curr Sci. 90:225–232.

- Lokho A. 2012. The folk medicinal plants of the Mao Naga in Manipur, North East India. Int J Sci Res Pub. 2:1–6.

- Maikhuri RK, Gangwar AK. 1993. Ethnobiological notes on the Khasi and Garo tribes of Meghalaya, Northeast India. Economic Bot. 47:345–357. doi: 10.1007/BF02907348

- Majumdar RK, Roy D, Bejjanki S, Bhaskar N. 2016. Chemical and microbial properties of shidal, a traditional fermented fish of Northeast India. J Food Sci. Technol. 53:401–410. doi: 10.1007/s13197-015-1944-7

- Mao AA. 1998. Ethnobotanical observation of rice beer “Zhuchu” preparation by the Mao Naga tribe from Manipur (India). Bull Bot Survey India. 40:53–57.

- Mao AA, Hynniewta TM. 2000. Floristic diversity of North East India. J Assam Sci Soc. 41:255–266.

- Mao AA, Hynniewta TM, Sanjappa M. 2009. Plant wealth of Northeast India with reference to ethnobotany. Indian J Trad Know. 8:96–103.

- Mao AA, Odyuo N. 2007. Traditional fermented foods of the Naga tribes of Northeastern, India. Indian J Trad Know. 6:37–41.

- Medhi P, Kar A, Borthakur SK. 2013. Medicinal uses of wild edible plants among the Ao Nagas of Mokokchung and its vicinity of Nagaland, India. Asian Reson. 2:64–67.

- Mokoena MP, Mutanda T, Olaniran AO. 2016. Perspectives on the probiotic potential of lactic acid bacteria from African traditional fermented foods and beverages. Food Nutrition Res. 60:29630. doi:doi: 10.3402/fnr.v60.29630

- Ngachan SV, Mishra A, Choudhury S, Singh R, Imsong B. 2005. Nagaland – a world of its own. In: Col Ved Prakash, editor. Encyclopaedia of North-East India, Volume VI. Atlantic Publishers & Dist.

- Omizu Y, Tsukamoto C, Chettri R, Tamang JP. 2011. Determination of Saponin contents in raw soybean and fermented soybean foods of India. J Sci Ind Res. 70:533–538.

- O’sullivan L, Murphy B, McLoughlin P, Duggan P, Lawlor PG, Hughes H, Gardiner GE. 2010. Prebiotics from marine macroalgae for human and animal health applications. Mar Drugs. 8:2038–2064. doi: 10.3390/md8072038

- Panthari P, Kharkwal H, Kharkwal H, Joshi DD. 2012. Myricanagi: A review on active constituents, biological and therapeutic effects. Int J Pharm Pharmaceut Sci. 4: 39–42.

- Parvez S, Malik KA, Ah Kang S, Kim HY. 2006. Probiotics and their fermented food products are beneficial for health. J Appl Microbiol. 100:1171–1185. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.02963.x

- Patel RK, Singh A, Deka BC. 2008. Soh-Shang (Elaeagnus latifolia): an under-utilized fruit of North East region needs domestication. ENVIS Bull: Himalayan Ecol. 16:1–2.

- Pegu R, Gogoi J, Tamuli AK, Teron R. 2013. Ethnobotanical study of wild edible plants in Poba Reserved Forest, Assam, India: multiple functions and implications for conservation. Res J Agri Forestry Sci. 1:1–10.

- Pfoze NL, Kehie M, Kayang H, Mao AA. 2014. Estimation of ethnobotanical plants of the Naga of North East India. J Med Plant Stud. 2:92–104.

- Phurailatpam AK, Singh SR, Chanu TM, Ngangbam P. 2014. Phlogacanthus – an important medicinal plant of North East India: a review. African J Agri Res. 9:2068–2072. doi: 10.5897/AJAR2013.8134

- Phutthaphadoong S, Yamada Y, Hirata A, Tomita H, Taguchi A, Hara A, Limtrakul PN, Iwasaki T, Kobayashi H, Mori H. 2009. Chemopreventive effects of fermented brown rice and rice bran against 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone-induced lung tumorigenesis in female A/J mice. Oncol Report. 21:321–327.

- Potsangbam L, Ningombam S, Laitonjam WS. 2008. Natural dye yielding plants and indigenous knowledge of dyeing in Manipur, Northeast India. Indian J Trad Know. 7: 141–147.

- Premarani T, Chhetry GKN. 2011. Nutritional analysis of fermented soyabean (Hawaijar). Assam University J Sci Technol. 7:96–100.

- Rai AK, Palni U, Tamang JP. 2009. Traditional knowledge of the Himalayan people on production of indigenous meat products. Indian J Trad Know. 8:104–109.

- Rai N, Asati BS, Patel RK, Patel KK, Yadav DS. 2005. Underutilized horticultural crops in North Eastern region. ENVIS Bull: Himalayan Ecol. 13:13–26.

- Rajapakse N, Mendis E, Jung WK, Je JY, Kim SK. 2005. Purification of a radical scavenging peptide from fermented mussel sauce and its antioxidant properties. Food Res Int. 38:175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2004.10.002

- Ray M, Ghosh K, Singh SN, Mondal KC. 2016. Folk to functional: an explorative overview of rice-based fermented foods and beverages in India. J Ethnic Food. 3:5–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jef.2016.02.002

- Rehman HU, Gill MIS, Sidhu GS. 2014. Micropropagation of Kainth (Pyruspashia) - an important rootstock of pear in northern subtropical region of India. J Experiment Biol Agri Sci. 2:188–196.

- Renner SS, Pandey AK. 2013. The Cucurbitaceae of India: accepted names, synonyms, geographic distribution, and information on images and DNA sequences. PhytoKeys. 20:53–118. doi: 10.3897/phytokeys.20.3948

- Rolle R, Satin M. 2002. Basic requirements for the transfer of fermentation technologies to developing countries. Int J Food Microbiol. 75:181–187. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(01)00705-X

- Rout J, Sajem AL, Nath M. 2010. Traditional medicinal knowledge of the Zeme (Naga) tribe of North Cachar Hills District, Assam, on the treatment of diarrhoea. Assam Univ J Sci Technol. 5:63–69.

- Rout J, Sajem AL, Nath M. 2012. Medicinal plants of North Cachar Hills District of Assam used by Dimasa tribe. Indian J Trad Know. 11:520–527.

- Roy B, Kala CP, Farooquee NA, Majila BS. 2004. Indigenous fermented food and beverages: a potential for economic development of the high altitude societies in Uttaranchal. J Hum Ecol. 15:45–49.

- Roy B, Swargiary A, Giri BR. 2012. Alpinia nigra (family Zingiberaceae): an anthelmintic medicinal plant of North-East India. Adv Life Sci. 2:39–51. doi: 10.5923/j.als.20120203.01

- Roy M. 1997. Fermentation technology. In: Bag AK, editor. History of technology of India. New Delhi: Indian National Science Academy.

- Saikia B, Tag H, Das AK. 2007. Ethnobotany of foods and beverages among the rural farmers of Tai Ahom of North Lakhimpur district, Asom. Indian J Trad Know. 6:126–132.

- Samati H, Begum SS. 2007. Kiad, a popular local liquor of Pnar tribe of Jaintia hills district, Meghalaya. Indian J Trad Know. 6:133–135.

- Sanglakpam P, Mathur RR, Pandey AK. 2012. Ethnobotany of chothe tribe of Bishnupur district (Manipur). Indian J Nat Prod Resource. 3:414–425.

- Sarangthem K, Singh TN. 2003. Microbial bioconversion of metabolites from fermented succulent bamboo shoots during fermentation. Curr Sci. 84:1544–1547.

- Sarkar PK, Hasenack B, Nout MJR. 2002. Diversity and functionality of Bacillus and related genera isolated from spontaneously fermented soybeans (Indian kinema) and locust beans (African soumbala). Int J Food Microbiol. 77:175–186. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(02)00124-1

- Sarkar PK, Jones LJ, Craven GS, Somerset SM, Palmer C. 1997. Amino acid profiles of kinema, a soybean-fermented food. Food Chem. 59:69–75. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(96)00118-5

- Sarkar PK, Jones LJ, Gore W, Craven GS. 1996. Changes in soya bean lipid profiles during kinema production. J Sci Food Agri. 71:321–328. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0010(199607)71:3<321::AID-JSFA587>3.0.CO;2-J

- Sarkar PK, Morrison E, Tingii U, Somerset SM, Craven GS. 1998. B-group vitamin and mineral contents of soybeans during kinema production. J Sci Food Agri. 78:498–502. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0010(199812)78:4<498::AID-JSFA145>3.0.CO;2-C

- Sarkar PK, Tamang JP. 1995. Changes in the microbial profile and proximate composition during natural and controlled fermentations of soybeans to produce kinema. Food Microbiol. 12:317–325. doi: 10.1016/S0740-0020(95)80112-X

- Sarmah R, Arunachalam A, Adhikari D. 2006. Indigenous technical knowledge and resource utilization of Lisus in the South eastern part of Namdapha National Park, Arunachal Pradesh. Indian J Trad Know. 5:51–56.

- Sarojnalini C, Singh WV. 1988. Composition and digestibility of fermented fish foods of Manipur. J Food Sci Technol. 25:349–351.

- Sathe GB, Mandal S. 2016. Fermented products of India and its implication: a review. Asian J Dairy Food Res. 35:1–9. doi: 10.18805/ajdfr.v35i1.9244

- Sathivel S, Bechtel P, Babbitt J, Smiley S, Crapo C, Reppon K. 2003. Biochemical and functional properties of herring (Clupea harengus) byproducts hydrolysates. J Food Sci. 68:2196–2200. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2003.tb05746.x

- Schippmann U, Cunningham AB, Leaman DJ. 2002. Impact of cultivation and gathering of medicinal plants on biodiversity: global trends and issues in biodiversity and the ecosystem approach in agriculture, forestry and fisheries. Rome: FAO.

- Seal T. 2011. Antioxidant activity of some wild edible fruits of Meghalaya State in India. Adv Biol Res. 5:155–160.

- Sekar S, Kandavel D. 2002. Patenting microorganisms: towards creating a policy framework. J Intellectual Properties Right. 7:211–221.

- Sekar S, Mariappan S. 2007. Usage of traditional fermented products by Indian rural folks and IPR. Indian J Trad Know. 6:111–120.

- Seshadri S, Srivastava U. 2002. Evaluation of vegetable genetic resources with special reference to value addition. In: International Conference on Vegetables, Bangalore, Bangalore; p. 41–62.

- Shankar R, Tripathi AK, Kumar A. 2014. Conservation of some pharmaceutically important medicinal plants from Dimapur District of Nagaland. World J Pharma Res. 3:856–871.

- Sharma PC, Bhatia V, Bansal N, Sharma A. 2007. A review on Bael Tree. Nat Product Radiance. 6:171–178.

- Sivanathan M. 2013. Pharmacological activities of Andrographis paniculata, Allium sativum and Adhatoda vasica. Int J Biomol Biomed. 3:13–20.

- Somishon K, Thahira Banu A. 2013. Hawaijar – a fermented Soya of Manipur, India: review. IOSR J Environ Sci, Toxicol Food Technol. 4:29–33. doi: 10.9790/2402-0422933

- Stanbury PF. 1999. Fermentation technology. In Stanbury PF, Whitaker A, Hal SJ, editors. Principles of fermentation technology. 2nd ed. Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann; p. 1–24.

- Steinkraus KH. 2002. Fermentations in world food processing. Compr Rev Food Sci F. 1:23–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-4337.2002.tb00004.x

- Steinkraus. 2004. Origin and history of food fermentation. In: Hui YH, Meunier-Goddik L, Josephsen J, Nip W-K, Stanfield PS, editors. Hand book of food and beverage fermentation technology. New York: Marcel Dekker; p. 1–8.

- Tamang JP. 2001. Kinema. Food Culture 3:11–14.

- Tamang JP. 2010. Himalayan fermented foods: microbiology, nutrition and ethnic value. New York: CRC Press, Taylor and Francis Group.

- Tamang JP. 2013. Animal-based fermented foods of Asia. Chapter 4. In: Hui YH, Özgül E, editors. Animal-based fermented foods. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press; p. 61–67.

- Tamang JP. 2015. Naturally fermented ethnic soybean foods of India. J Ethnic Food. 2:8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jef.2015.02.003

- Tamang JP, Chettri R, Sharma RM. 2009. Indigenous knowledge on North-East women on production of ethnic fermented soybean foods. Indian J Trad Know. 8:122–126.

- Tamang JP, Dewan S, Thapa S, Olasupo NA, Schillinger U, Holzapfel WH. 2000. Identification and enzymatic profiles of predominant lactic acid bacteria isolated from soft-variety chhurpi, a traditional cheese typical of the Sikkim Himalayas. Food Biotechnol. 14:99–112. doi: 10.1080/08905430009549982

- Tamang JP, Nikkuni S. 1998. Effect of temperatures during pure culture fermentation of Kinema. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 14:847–850. doi: 10.1023/A:1008867511369

- Tamang JP, Sarkar PK. 1993. Sinki: a traditional lactic acid fermented radish tap root product. J General Appl Microbiol. 39:395–408. doi: 10.2323/jgam.39.395

- Tamang JP, Sarkar PK. 1996. Microbiology of mesu, a traditionally fermented bamboo shoot product. Int J Food Microbiol. 29:49–58. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(95)00021-6

- Tamang B, Tamang JP. 2007. Role of lactic acid bacteria and their functional properties in Goyang, a fermented leafy vegetable product of the Sherpas. J Hill Res. 20:53–61.

- Tamang B, Tamang JP. 2009a. Traditional knowledge of biopreservation of perishable vegetables and bamboo shoots in Northeast India as food resources. Indian J Trad Know. 8:89–95.

- Tamang B, Tamang JP. 2009b. Lactic acid bacteria isolated from indigenous fermented bamboo products of Arunachal Pradesh in India and their functionality. Food Biotechnol. 23:133–147. doi: 10.1080/08905430902875945

- Tamang B, Tamang JP. 2010. In situ fermentation dynamics during production of gundruk and khalpi, ethnic fermented vegetable products of the Himalayas. Indian J Microbiol. 50:93–98. doi: 10.1007/s12088-010-0058-1

- Tamang B, Tamang JP, Schillinger U, Franz CMAP, Gores M, Holzapfel WH. 2008. Phenotypic and genotypic identification of lactic acid bacteria isolated from ethnic fermented bamboo tender shoots of North East India. Int J Food Microbiol. 121:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.10.009

- Tamang JP, Tamang B, Schillinger U, Franz CMAP, Gores M, Holzapfel WH. 2005. Identification of predominant lactic acid bacteria isolated from traditionally fermented vegetable products of the Eastern Himalayas. Int J Food Microbiol. 105:347–356. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2005.04.024

- Tamang JP, Tamang N, Thapa S, Dewan S, Tamang B, Yonzan H, Rai AP, Chettri R, Chakrabarty J, Kharel N. 2012. Micro-organism and nutritive value of ethnic fermented foods and alcoholic beverages of North-East India. Indian J Trad Know. 11:7–25.

- Tamang JP, Thapa S. 2006. Fermentation dynamics during production of BhaatiJaanr, a traditional fermented rice beverage of the eastern Himalayas. Food Biotechnol. 20:251–261. doi: 10.1080/08905430600904476

- Tamang JP, Thapa N, Rai B, Thapa S, Yonzan H, Dewan S, Tamang B, Sharma RM, Rai AK, Chettri R, et al. 2007. Food consumption in Sikkim with special reference to traditional fermented foods and beverages: a micro-level survey. J Hill Res. 20:1–37.

- Tamang JP, Thapa S, Tamang N, Rai B. 1996. Indigenous fermented food beverages of Darjeeling hills and Sikkim: process and product characterization. J Hill Res. 9:401–411.

- Tamang JP, Watanabe K, Holzapfel WH. 2016. Review: diversity of microorganisms in global fermented foods and beverages. Frontier Microbiol. 7:377. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00377

- Thakur K, Rajani CS, Tomar SK, Panmel A. 2016. Fermented bamboo shoots: a riche niche for beneficial microbes. J Bacteriol Mycol. 2:2–8. doi: 10.15406/jbmoa.2016.02.00030

- Thapa N, Pal J, Tamang JP. 2004. Microbial diversity in ngari, hentak and tungtap, fermented fish products of North-East India. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 20:599–607. doi: 10.1023/B:WIBI.0000043171.91027.7e

- Thapa N, Pal J, Tamang JP. 2006. Phenotypic identification and technological properties of lactic acid bacteria isolated from traditionally processed fish products of the Eastern Himalayas. Int J Food Microbiol. 107:33–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2005.08.009

- Thapa N, Pal J, Tamang JP. 2007. Microbiological profile of dried fish products of Assam. Indian J Fisheries. 54:121–125.

- Thapa S, Tamang JP. 2004. Product characterization of kodokojaanr: Fermented finger millet beverages of the Himalayas. Food Microbiol. 21:617–622. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2004.01.004

- Tiwari SC, Mahanta D. 2007. Ethnological observations fermented food products of certain tribes of Arunachal Pradesh. Indian J Trad Know. 6:106–110.

- Umdor M, Kyndiah E, Mawlong HML. 2016. Indigenous knowledge in preparing rice based foods by the tribes of Meghalaya. Int J Innovative Res Adv Stud. 3:234–241.

- Uniyal AK, Hamtoshi BS, Nazir T. 2014. Potential of important agriculture crops under medicinal agroforestry tree species in Nagaland, North-east Himalaya, India. Indian Forester. 140:494–507.

- Vijayendra SVN, Halami PM. 2015. Health benefits of fermented vegetable products. In Tamang JP, editor. Health benefits of fermented foods and beverages. Boca Raton (NY): CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group; p. 325–342.

- Yadav AK, Tangpu V. 2012. Anthelmintic activity of ripe fruit extract of Solanum myriacanthum Dunal (Solanaceae) against experimentally induced Hymenolepis diminuta (Cestoda) infections in rats. Parasitol Res. 110:1047–1053. doi: 10.1007/s00436-011-2596-9

- Yonzan H, Tamang JP. 2009. Traditional processing of Selroti – a cereal-based ethnic fermented food of the Nepalis. Indian J Trad Know. 8:110–114.