ABSTRACT

The transition out of university can be a challenging time for undergraduate students, especially those with mental health conditions (MHC). Student mental health is a global concern, and metrics indicate lower employment rates for graduates with MHC. Little is known about the expectations and experiences of these students regarding this transition. This research used mixed methods to gather information on transition expectations prior to graduation (Study One), and experiences after graduation (Study Two). In Study One, 44 final year undergraduate students with MHC registered with their disability service and 50 without completed a survey, examining emotions and expectations of the transition. Study Two involved semi-structured interviews with seven graduates with MHC. Study One found students with MHC associated more negative emotions with the transition and were less likely to have a post-graduation plan but were not accessing more support than those without MHC. Study Two highlighted challenges faced when accessing support, the impact of mental health on transitions, and coping with change. These findings have implications for Higher Education providers in ensuring better support is available for the transition out of university for students with MHC. Specific support tailored to the needs of these students could help improve graduate outcomes.

Introduction

For undergraduate students, the transition out of university can be challenging. The transition involves leaving a familiar environment, potential loss of support, and entering a new workplace or postgraduate course where expectations differ (Lane Citation2015). Successful transition into work or further study is important for students themselves and their universities. Metrics on graduate employability are critical for universities (Christie Citation2017) but indicate poorer outcomes for students with mental health conditions (MHC) (Association of Graduate Careers Advisory Services (AGCAS) Citation2018). It is vital we fully understand this transition and ensure universities provide appropriate support.

The transition out of university can be psychologically demanding (Polach Citation2004), irrespective of MHC. For those entering university after school, university can prolong the transition to adulthood, with graduating constituting a major life event (Grosemans et al. Citation2018). When graduating, students must make sense of their identity and career path (Lane Citation2015). This transition is accompanied with feelings of uncertainty, discomfort and low mood (Perrone and Vickers Citation2003). Low belief in how well one can manage the transition and low perceived adulthood status could link to greater difficulties (Halstead and Lare Citation2018). Further, if an individual struggles to find employment, this can negatively impact wellbeing (Paul and Moser Citation2009). It is likely this transition is more challenging for students with MHC, yet there is little research examining the experiences of these students.

The mental health of students is a global concern, with increasing numbers of students reporting mental health difficulties around the world (Holm-Hadulla and Koutsoukou-Argyraki Citation2015). For example, in the UK 96,490 students disclosed MHCs to their university in 2019/20 (4.86% of total student population) compared to 33,500 in 2014/15 (1.79%; HESA Citation2021). Common MHC for students include depression and anxiety (Auerbach et al. Citation2016), which impact on self-esteem, motivation and academic and social functioning (Kitzrow Citation2003). Further, there are likely many students with undisclosed or undiagnosed MHCs (Eisenberg, Golberstein, and Gollust Citation2007) – generally, students report high anxiety (Neves and Hillman Citation2017; Holm-Hadulla and Koutsoukou-Argyraki Citation2015), psychological distress and suicidal ideation (Eskin et al. Citation2016).

Employment statistics for graduates with MHC suggest they experience additional difficulties with the transition. Six months after graduating, around 40% of UK graduates with MHC are in full-time work, compared to 70% of peers with no known disabilities (AGCAS Citation2018). Additionally, graduates with MHC are twice as likely to be unemployed (AGCAS Citation2018). These statistics are despite students with MHC being just as likely to graduate with an upper second-class or first-class degree (Richardson Citation2009). Those with anxiety may worry more about unknowns after university (American Psychiatric Association Citation2013), and anxiety may negatively affect job-seeking behaviours (Wang et al. Citation2017). Individuals with depression may think negatively about their future (Lavender and Watkins Citation2004) and low motivation, decision-making difficulties and feelings of worthlessness (APA Citation2013), could make the transition more difficult. MHCs could affect the way individuals process transitions and cope with change (Dvořáková, Greenberg, and Roeser Citation2019).

The lack of evidence on university transitions is problematic as students with MHC are vulnerable during transition periods, with an increased suicide risk (Stanley et al. Citation2009). Our research aimed to explore expectations and experiences of the transition out of university for students with MHC in the United Kingdom, using mixed methods. The experience of the transition will be bound within cultural contexts: in the UK, most graduates are employed 15 months after graduating, with 5.5% unemployed (Ball et al. Citation2020). The UK labour market is also considered relatively stable (Ball et al. Citation2020). Therefore, experiences and expectations of UK students could differ to students in other countries.

In Study One, students with MHC completed a survey examining their expectations of the transition during the final six months of their degree. A group with no known disability were recruited to compare experiences. We predicted students with MHC would report more negative emotions and greater transition concerns. Taking a mixed-methods approach enabled us to examine potential differences in expectations and gain in-depth understanding of transition experiences. In Study Two, graduates with MHC participated in an interview regarding experiences of the transition post-graduation. Qualitative methods were deemed appropriate since the topic has been relatively unexplored, and this approach could deepen understanding and prioritise lived experience (Gewurtz et al. Citation2016). We focused only on graduates with MHC as there is a paucity of research with this group, and we aimed to understand their experiences in-depth. In contrast, there are pre-existing studies on transition experiences with other groups without (reported) MHC, for example, women (Finn Citation2017), international students (Popadiuk and Arthur Citation2014), engineering students (Stiwne and Jungert Citation2010), autistic students (Pesonen et al. Citation2020) and other disabilities (Gillies Citation2012; Nolan and Gleeson Citation2017). This study was exploratory, given the lack of pre-existing research on this topic.

Study One: expectations of the transition

Methods

Participants

Ninety-four final year undergraduate students were recruited from three universities in South East England through adverts on campus, word-of-mouth and Disability Services. Forty-four reported MHC and were registered with their Disability Service (7 male, 37 female). Fifty students in the comparison group reported no diagnosed MHC or other disabilities (19 male, 31 female). Further demographic details are shown in . In the MHC group, 35 reported a diagnosis of anxiety, 30 depression, and 13 reported other mental health conditions, including personality disorders (n = 5) or eating disorders (n = 4). Twenty-six reported more than one MHC, and seven reported other conditions such as ADHD, dyslexia or dyspraxia.

Ethical approval was obtained from all universities involved and participants gave full informed consent.

Materials and Procedure

Participants completed an online survey presented using ‘Qualtrics’. The survey took approximately 15 min and data were collected between December 2017 and May 2018. Participants first completed demographic information and questions regarding MHC (if applicable). Next, they completed the Warwick Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS; Tennant et al. Citation2007) to measure mental wellbeing. This measure consisted of 14 items (e.g. ‘I’ve been feeling cheerful’) rated on a 5-point scale (‘none of the time’ to ‘all of the time’). Higher scores indicate higher wellbeing. Internal consistency was excellent (α = .95).

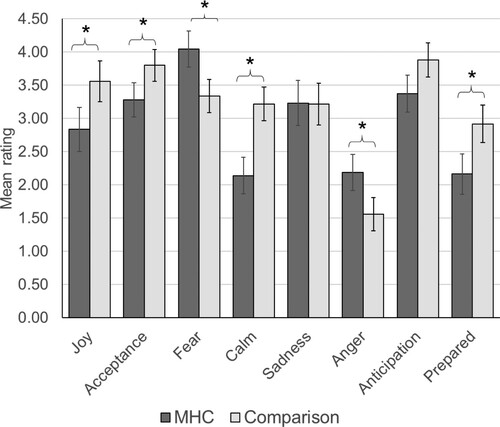

Participants completed questions regarding their degree before answering questions on transition expectations. They rated emotions towards the transition, in terms of anger, anticipation, fear, joy, sadness, acceptance, calm and preparedness. The first seven emotions were based on Plutchik's (Citation1991) Wheel of Emotions and participants rated each on a 5-point Likert scale (‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’). They also rated how supported they felt by their university in preparing for the transition on a 5-point scale (‘not very well supported’ to ‘very well supported’). Participants indicated whether they had accessed emotional support for the transition, e.g. from a specialist mentor or personal tutor. For support accessed, they rated how helpful it had been on a 5-point scale (‘not at all’ to ‘very helpful’). We then asked an open question: ‘What do you think the three main challenges/strengths faced by students [with MHC] are when they graduate?’.

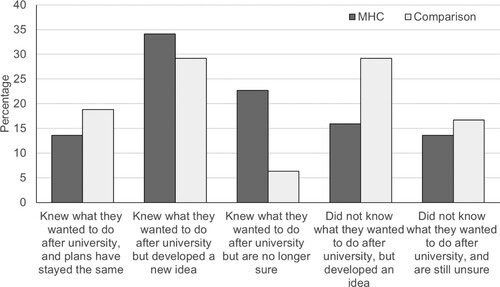

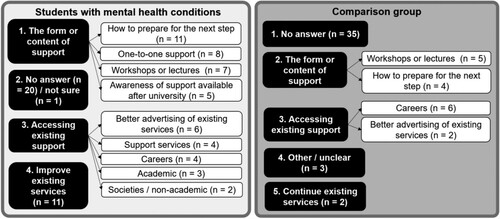

Participants completed questions regarding plans post-graduation. They indicated plans for the first six months after graduating (e.g. employment, postgraduate study) then described how their plans had developed, selecting from options including ‘I knew what I wanted to do after university, and my plans have stayed the same’ or ‘I did not know what I wanted to do after university, and I am still unsure what I will do’. Participants indicated how supported they felt by their university in preparing for their career, on the same 5-point scale. They selected what career-focused support they had accessed and rated how helpful it had been (as above). Participants indicated in an open textbox if there was any additional support they thought universities should provide for students [with MHC] to help with the transition out of university or careers development.

Design and analysis

Study One had an exploratory, cross-sectional survey design. Descriptive statistics and parametric and non-parametric statistics are reported as appropriate. Gender was controlled for due to the differences in gender distribution between groups. Qualitative responses were analysed using content analysis (Hsieh and Shannon Citation2005): responses from the two groups were analysed separately to see if unique categories were identified in each group.

Results

Emotions towards the transition

The MHC group had significantly lower wellbeing scores (M = 37.63, SD = 12.11) than the comparison group (M = 49.82, SD = 7.49), t(69.86) = 5.77, p < .001. Population surveys indicate the general public mean is 51, and scores below 42.5 indicate low wellbeing (Braunholtz et al. Citation2007).

A 2 (group) × 8 (emotion) mixed ANCOVA controlling for gender tested for differences in emotion ratings. There was a significant main effect of group (F(1, 90) = 14.18, p < .001, ηp2 = .14), with emotions rated lower by the MHC group (M = 2.91) than the comparison group (M = 3.19). There was a significant main effect of emotion (F(7, 630) = 3.32, p = .002, ηp2 = .036), with differences in ratings of each emotion (not explored due to significant interactions). There was a significant interaction between emotion and gender (F(7, 630) = 3.62, p = .001). Post-hoc analyses adjusting for multiple comparisons using Bonferroni (corrected p value = .006) found significant differences between fear (male M = 3.00, female M = 3.93, p < .001) and calm (male M = 3.35, female M = 2.48, p < .001). There was a significant interaction between emotion and group (F(7, 630) = 8.55, p < .001, ηp2 = .087). Post-hoc analysis showed the MHC group gave higher ratings of fear (p=.005) and anger (p = .002), and lower ratings of joy (p = .002), acceptance (p = .006), calm (p < .001), and preparedness (p = .003; ).

Emotional support for the transition

There was no difference in how supported either group felt in preparing for the transition (t(91) = .68, p = .51; MHC M = 2.62 (SD = 1.07), comparison M = 2.76 (SD = .87)). For emotional support, both most often used their personal tutor (). Most support was rated neutrally for helpfulness. There was no association between group and accessing emotional support of any form (MHC = 59.1% versus comparison = 42.0%, X2(1) = 2.74, p = .098, 2-sided).

Table 1. Emotional and career support accessed for the transition and ratings of helpfulness.

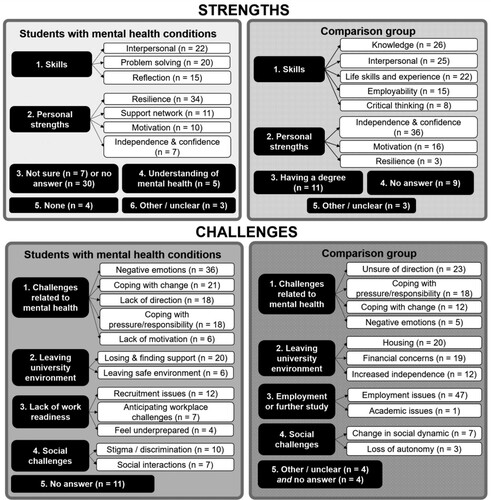

Strengths and challenges

For students with MHC, strengths were categorised as skills or personal strengths (; example quotes in ). For skills, this included interpersonal skills, problem-solving and self-reflection. Personal strengths included resilience, support networks, motivation, independence and confidence. Some mentioned understanding mental health or said there were no strengths. Many were not sure or had no answer. The comparison group also reported strengths around skills and personal characteristics, focusing on knowledge gained, interpersonal skills, life experience, employability and critical thinking. For personal strengths, they mentioned independence and confidence, motivation, and resilience. Uniquely this group mentioned having a degree was a strength.

Figure 2. Strengths and challenges for students with and without mental health conditions when they graduate, identified following content analysis.

For challenges, students with MHC most often discussed mental health challenges, including negative emotions, coping with change, lacking direction, coping with responsibility or lacking motivation. Other challenges related to leaving university, such as losing support and leaving a safe environment. Less often, participants discussed feeling little work readiness, with concerns about recruitment or workplace challenges. Some mentioned worries about stigma or social interactions. In the comparison group, the most frequently reported challenges related to mental health, with participants feeling unsure of their direction, coping with responsibility, change and negative emotions. They also discussed challenges related to leaving university, but focused on housing, finances and increased independence. Finding employment was frequently cited as a challenge. Social challenges related to changes in social dynamics and loss of autonomy.

Career plans

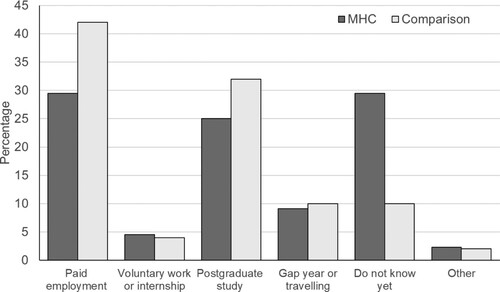

For post-graduation plans (), most in the MHC group intended to go into paid employment or did not know. Most of the comparison group intended to go into paid employment or postgraduate study. There was a significant association between group and having plans (X2(1) = 5.58, p = .016, 2-sided), with the MHC group less likely to have a plan.

Figure 3. Post-graduation plans for students with mental health conditions (MHC) and comparison group.

Participants reported how their career plans developed during university (), with most in the MHC group developing new career ideas or had once had ideas but now felt unsure. In the comparison group, most had developed new ideas or originally had no plan but had since developed ideas.

Career support

There was no significant difference in how supported by their university the groups felt for careers, t(71.67) = .50, p = .62; MHC M = 2.74 (SD = 1.19), comparison M = 2.85 (SD = .82). Both most often used personal tutors for career support, with around 25% utilising the careers service (). Most support was rated as helpful. There were no differences between MHC (52.3%) and the comparison group (54.0%) in terms of accessing any career support (X2(1) = .028, p = .87, 2-sided).

Additional support

Students with MHC most often discussed the form of support (, ), desiring advice on preparing, one-to-one support, workshops or lectures, and more awareness of support available after university. Some discussed needing help to access current support, including better advertising of existing services. Some discussed improving current services, noting a lack of understanding of mental health. Twenty-one provided no answer or were unsure. In the comparison group, most gave no answer. Those who did mentioned the form of support should be workshops or lectures, focusing on how to prepare. Some discussed accessing existing support such as careers services and better advertising. Two mentioned current services could continue as they are.

Summary of Study one

Study One indicated students with MHC have different emotions and expectations of the transition compared to their peers. They reported more negative emotions, most often fear, compared to acceptance and anticipation in the comparison group. However, students with MHC were not accessing more emotional support, with 40% not accessing support at all. While both groups qualitatively reported feeling unsure of their direction after graduating, those with MHC were significantly less likely to have career plans, with many reporting they previously knew what they wanted to do but now did not. Yet the MHC group were not utilising more careers support than the comparison group. For both, only one in four had used careers services, and were most likely to use personal tutors for careers and emotional support. Support from universities was rated as generally helpful or neutrally. Qualitative responses indicated more preparatory support is needed and current support could be better advertised. Notably, students in the comparison group discussed mental health challenges relating to the transition but also focused more on practical challenges around employment, accommodation, or finances.

Study Two: experiences of the transition

Methods

Participants

We invited students with MHC who had taken part in Study One to participate in an interview after graduation. Seven graduates (six female, one male) participated (mean age 21.71, SD = 1.38; see for further details). Participants had multiple diagnoses: six reported depression, five anxiety, two eating disorders, and one reported Borderline Personality Disorder. Three studied Psychology, two Creative Writing, one Primary Education and one Physics. Three achieved a first-class degree and four an upper second-class degree. Participants gave full informed consent before participation. Ethical approval was obtained from all universities.

Materials and procedure

Interviews were semi-structured, considering experiences post-graduation. Topics included: support at university, feelings about the transition since graduating, plans for the next six months, how MHCs had affected their experiences, and advice they would give to students with MHC. Interviews took place over the phone with a research assistant, lasting 20 min on average. Interviews were conducted in August 2018, after graduation in July 2018.

Design and analysis

Interviews were transcribed verbatim and analysed using Thematic Analysis and steps outlined by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006) to identify patterns in participants’ experiences. One author (VN) conducted the analysis with theme reviewing and defining completed in discussion with another author (EC). Themes were developed at the semantic level, linked closely to participants’ experiences, and the analysis was inductive (Braun and Clarke Citation2006).

Results

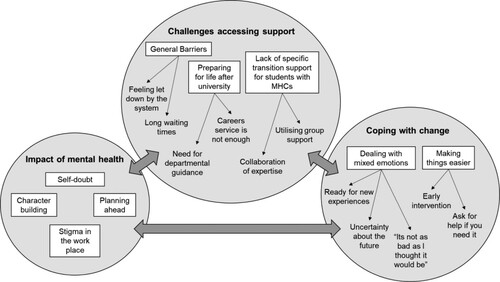

Themes were organised according to three categories: challenges accessing support, impact of mental health, and coping with change ().

Figure 6. Thematic map of experiences of the transition out of university for graduates in the sample.

Challenges accessing support

Theme One: General barriers. Participants accessed various forms of support at university. Some found the support helpful, however there were many unmet needs. Barriers to accessing support were not specific to the transition but may have impacted on accessing transition-related support:

Subtheme: Long waiting times. When requiring support, participants highlighted long waiting times. They were aware services were in high demand, but by the time support was offered, it was insufficient: ‘I did go to the disability team for help … I didn’t feel I really got anything there and I had to wait quite a long time.’ (ID3)

Subtheme: Feeling let down by the system. Many described support from their university as ineffective or not relevant to their MHC. Others felt external services provided better support. This led to participants feeling disappointed:

I feel like that those [university] counselling sessions would have helped me in the transition. But by the time they’d got to me, I didn’t need it. Well, I probably did need it, but I didn’t want it anymore and I felt let down by them. (ID7)

Subtheme: Careers service is not enough. Participants who accessed the careers service felt it had been unhelpful. They commented on how advice was generic and the service’s purpose unclear:

We all know that the careers and employability service is there, but I don’t really know if it was there for the transition, or it was more to get you a job part-time and things like that whilst you’re at uni (ID5).

Subtheme: Need for departmental guidance. Participants that received support within their department felt it was most beneficial. This perception was attributed to departmental staff having knowledge of career paths and experience:

I would definitely recommend departments have their own careers advisor. They have a lot more knowledge about what parts of the degree are like. They get to know you better, so their help was more useful than the one provided by the careers service (ID6).

Subtheme: Collaboration of expertise. Participants discussed how MHC transition support should be a joint effort across departments, careers and disability services. There were suggestions of a specific contact: ‘I think there could be a specific person within the disability services who deals with [the] transition out.’ (ID5)

Subtheme: Utilising group support. Group sessions were a common suggestion – participants would feel more confident discussing concerns if they could attend with friends. However, one-to-one sessions could still be offered to those interested: ‘I think if it’s something really personal, one-to-one will be better, but if it’s something quite generic, [e.g.] talking about moving on from university and doing taxes and stuff, that could be a group.’ (ID3)

Impact of mental health

Four themes were identified in terms of the impact MHCs had on transition experiences:

Theme Four: Character Building. Many felt MHCs helped with the transition, encouraging them to grow, develop strength and enhanced empathy: ‘I suppose it’s given me more experience. I can speak to other people about it, and I feel that I might be a bit stronger through it’ (ID3).

Theme Five: Planning ahead. Participants felt MHCs pushed them to spend additional time preparing. They had researched different companies, interview performance, and developed in-depth knowledge of their career path. For some, this was anxiety-driven: ‘Because I’ve got anxiety, I always think of the worst scenarios and compensate for that. Because I know how competitive it is to get onto [postgraduate study], I’ve volunteered and got loads of experience’ (ID1).

Theme Six: Stigma in the workplace. Some commented on believing MHCs were disadvantageous to their career. Experiences included being advised against having mental health assessments, believing showing symptoms would increase the risk of being fired, and blaming themselves for not coping in workplace environments:

I started work experience this week, and I wasn’t prepared for how unwelcoming [it was]. That caused me to have an anxiety attack, and I think if I didn’t have [MHCs], maybe I wouldn’t have been so affected by it. (ID7)

Coping with change

These themes reflected on feelings towards the transition and how participants coped with the changes that accompanied it:

Theme Eight: Dealing with mixed emotions. The transition was associated with mixed emotions:

Subtheme: Uncertainty about the future. Ambiguity surrounding what life would be like after university played a role in negative feelings towards the transition. Some commented on experiencing increased anxiety about university ending and others felt unprepared:

I got very anxious about the next step, I didn’t want to think about it or do anything about it, and I think in a way that made my anxiety a lot worse […] It was the unknown, and having to make those steps to the future, that made me anxious. (ID1)

Subtheme: ‘It’s not as bad as I thought it would be’. All commented on how the transition was better than they had anticipated: ‘I thought it would be much more difficult to change from being at university to going into the real world’ (ID2). Some acknowledged that even though they were still feeling anxious or unprepared, these feelings were expected:

I don’t feel fully prepared, but I don’t think you can feel fully prepared ever really. And that’s not the university’s fault, you spend so much time in one place, doing the same thing. I think it’s hard to get out of that habit really. (ID7)

Subtheme: Early intervention. Most advised preparing early. Doing so helped relieve pressure during final year, and was less taxing on mental health during a stressful time:

If you think about your options early on, maybe towards the start of third year, it’s not going to feel so rushed and pressured. Then when you’re coming to the end you know what’s happening next, it’s not just ‘this is the end of everything’ (ID1).

If they need help, they should definitely go and talk to someone, because the worst thing they can do is just to keep it bottled up. At the end of the day, that could potentially affect the outcome of their degree if they’re not getting the support they need (ID4).

Summary of Study Two findings

Study Two adds to Study One by following up with a subset of participants post-graduation, to establish whether transition experiences aligned with expectations, and to reflect on support needed. Study Two highlighted several issues faced by graduates with MHC: When accessing support, they experienced long waiting times and felt let down by university services. Participants stressed the need for subject-specific careers guidance and noted little transition support specifically for students with MHCs. Participants believed MHCs could be both hindering or helping their career development. When going through the transition, participants experienced mixed emotions, feeling nervous but excited for the future. All reported finding the transition better than expected.

General discussion

This research explored expectations and experiences of the transition out of university for students with MHC. Pre-transition, students with MHC felt more negative emotions than their peers. Post-transition, interviewees discussed having mixed emotions, but the transition was better than they were anticipating. Despite potentially needing more support, those with MHC were not accessing more pre-transition support than their peers. Interview data indicated issues with accessing support due to long waiting times or feeling disappointed in the support available. Interviewees suggested transition support specifically for students with MHC might be beneficial. Concerningly, before the transition those with MHC were less likely to have a plan for after graduation. Both groups used their personal tutor most for support, and interviewees discussed uncertainties about the careers service and preferences for department-specific support. Further, interviewees discussed how MHCs affected the transition. While they had self-doubt and stigma concerns, they believed MHCs helped them plan and develop personally. Our findings have important implications for universities and indicate current support could be improved.

In terms of emotional support, the nature of certain MHCs may mean students ruminate or focus on negatives (APA Citation2013). Pre-transition, the most endorsed emotion was fear, and post-transition, graduates elaborated on fears about uncertainty. Universities should support students with MHC to reduce uncertainties. In the UK, students who register with their disability service have access to support from disability advisors or specialist mentors in addition to universally-available support. However, our findings indicated students with MHC were not accessing more support or feeling more supported. There are several reasons why they may not seek support, including denying the existence of a problem, perceiving problems as not serious enough, prior negative experiences or believing support would be unhelpful (Andrews, Henderson, and Hall Citation2001; Vanheusden et al. Citation2008). Self-stigma could be a barrier experienced by students seeking support for mental health (Cage et al. Citation2018; Quinn et al. Citation2009). They may not realise the possibility of transition support, and no interviewees were aware of any specialised support. Qualitative data pre-transition indicated universities could better to advertise current support. Importantly, students in the comparison group mentioned similar mental health challenges – indicating the transition can be emotionally difficult for all students, thus support should be designed following Universal Design principles, whereby increasing accessibility benefits all students (Gradel and Edson Citation2009).

Interviewees discussed issues with support, such as long waiting times, an issue identified previously (Batchelor et al. Citation2020). Long waiting times are problematic since they may contribute to poorer mental health and longer recovery (Reichert and Jacobs Citation2018). With the transition, students are faced with loss of support from mentors or personal tutors. Participants suggested a specific contact within disability services who helps final year students know what support is available outside of university may be beneficial. It may also be that some students require more specialist mental health support than universities can offer. When discussing specialised transition support, interviewees mentioned how collaboration of expertise was needed across different departments and services. A ‘whole university’ approach has been recommended for improving student mental health (Hughes and Spanner Citation2019), and we would argue that transitions out of university must be included as part of the whole.

Emotional aspects of the transition are inter-linked with career planning. Our research highlights issues that may link to lower employment rates reported amongst graduates with MHC (AGCAS Citation2018). In our survey, those with MHC were less likely to have plans and many were now unsure despite once having a plan. Previous research has shown depressed undergraduate students report higher rates of career indecision and dysfunctional career thoughts (Saunders et al. Citation2000). In pre-transition qualitative data, the comparison group more often mentioned independence and confidence as a strength compared to those with MHC. Universities could consider how to increase the confidence of students with MHC pre-transition – our interviewees suggested group sessions may be beneficial for imparting advice and planning ahead. Early structured discussions about post-university plans could be implemented by personal tutors, disability advisors or mentors.

Around a quarter of participants (in both groups) had used their careers service, but qualitative responses indicated some uncertainties about the service. Interviewees reported feeling the careers service was ‘not enough’, desired more subject-specific guidance, and had concerns careers events were not accessible. Further, some believed there would be mental health stigma in the workplace. Australian students have also expressed concerns over stigma within employment (Martin Citation2010) and generally students with MHC discuss concerns over stigma (Hartrey, Denieffe, and Wells Citation2017; Kain, Chin-Newman, and Smith Citation2019). These findings suggest reducing stigma and improving accessibility is vital. One option may be to train all staff, who are often untrained about mental health (Margrove, Gustowska, and Grove Citation2014) and ensure transition-related events are designed with accessibility in mind.

For support desired, participants in both groups mentioned workshops/lectures, needing advice on preparing for the transition, and better advertising of existing support. In interviews, graduates mentioned potential benefits of group support. Accordingly, peer mentoring or support groups focusing on the ‘next steps’ may be beneficial for the transition out, as research suggests this is potentially useful for the transition to university (Hillier et al. Citation2019). A systematic review of barriers and facilitators for students with MHC (irrespective of transitions) noted the need for peer support and better integrated support from services (Hartrey, Denieffe, and Wells Citation2017). Finally, our interviewees mentioned ‘asking for help when needed’, which relates to self-advocacy. Self-advocacy skills have been shown to relate to more positive transitions to university for disabled students (Adams and Proctor Citation2010), therefore research should examine how supporting self-advocacy may assist with the transition out.

Our findings indicated that participants preferred to utilise their department, including personal tutors, for support. However, personal tutors are usually academic staff who may not have received MHC training (Margrove, Gustowska, and Grove Citation2014), nor are they specialists in career guidance. Academics may find themselves affected by the demands placed on them (Hughes et al. Citation2018), and feel they are not receiving appropriate support for their own mental wellbeing (Kinman and Jones Citation2008). Thus, to support students with the transition, personal tutors must be supported appropriately, as well as trained to signpost to services. However, the focus should not only be on university support, as workplaces must be accessible and open to supporting the needs of graduate employees with MHC. It is important universities work collaboratively with employers and community support services to facilitate better transition experiences.

Finally, it is worth viewing our findings within context. All participants were students at English universities. Here, HE has become marketized, driven by competition, managerialism and commodification, arguably at the expense of staff, students, and academia itself (Taberner Citation2018; Molesworth, Nixon, and Scullion Citation2009). Employability is a ‘return’ from a degree that may lead to certain expectations (Tomlinson Citation2017) – namely that a ‘good’ degree is a guarantee for a professional job (Molesworth, Nixon, and Scullion Citation2009). Future research would benefit from analysing whether the marketisation of HE exacerbates challenges for students with MHC. For example, pressure to obtain a ‘good’ degree could worsen anxiety, and a qualitative study of academics in England suggested that psychological needs are less well met amongst students who identify as consumers (King and Bunce Citation2020). Another notable context is the COVID-19 pandemic, although we collected our data prior to this. We do not yet know the impact on employment for graduates since 2020: some anticipate a ‘profound effect’ (Ball et al. Citation2020). Studies during the pandemic have indicated increased levels of depression, anxiety and stress in students (Wang et al. Citation2020; Elmer, Mepham, and Stadtfeld Citation2020; Essadek and Rabeyron Citation2020; Savage et al. Citation2020). Additional support for the transition out of university for cohorts affected by the pandemic should be a priority.

Limitations

The perspectives of male students were under-represented. Females tend to be more likely to complete surveys (Sax, Gilmartin, and Bryant Citation2003) and may be more likely to report depression (Kuehner Citation2003) and anxiety (McLean et al. Citation2011). However, there are higher rates of suicide for males (Struszczyk, Galdas, and Tiffin Citation2019), thus it is vital male perspectives are included. Additionally, we did not record ethnicity or sexuality and will have missed how the intersection of different identities impact on experiences (Olney and Brockelman Citation2005). Further, most participants were young adults, following a path from school to HE. Our findings are not representative of mature students and some aspects of our participants’ experiences may be tied to ‘emerging adulthood’ (Arnett Citation2000). Further, our MHC group had registered with their disability service – therefore we miss the experiences of non-disclosing students. In Study One, the comparison group was not matched, e.g. on gender, degree subject; future research with larger samples could better account for both intersectionality and demographic factors. In Study Two, most interviewees had a career plan despite Study One data indicating students with MHC were less likely to have a plan. It is likely those with more positive transition experiences self-selected; those who had negative experiences or no plans may not have wished to participate in interviews. However, qualitative data does not claim to be generalisable (Braun and Clarke Citation2019) and our interviewees’ experiences are still valid.

Conclusion

This research highlights that students with MHC face difficulties with the transition out of university, particularly experiencing fears regarding the future. Positively, for our graduates the transition had not been as bad as they were anticipating. Thus, support provided by universities should reassure students with MHC before the transition to alleviate fears and develop confidence. Accessible, early support delivered by well-trained staff with collaboration between services and departments may be beneficial, as well as developing external partnerships with employers and community services. Students with MHC have an equal right to positive graduate outcomes, and it is time we achieve this equality.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to all the participants for their time and sharing their thoughts.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Eilidh Cage

Eilidh Cage is a Lecturer in Psychology at the University of Stirling. She is primarily an autism researcher, aiming to understand the experiences of autistic people particularly in relation to mental health and wellbeing, but she is also interested in understanding and improving wellbeing for all students. Prior to Stirling she was a teaching-focused Lecturer in Psychology at Royal Holloway, University of London. She is a Fellow of the HEA.

Alana I. James

Alana I. James is an Associate Professor in Psychology at the University of Reading. She is a teaching-intensive academic with a focus upon student support and experience. Her research has investigated peer support and mentoring in schools and universities, amongst other areas of educational and developmental psychology. She is a Senior Fellow of the HEA, and winner of the 2019 BPS DART-P/OUP Higher Education Psychology Teacher of the Year Award.

Victoria Newell

Victoria Newell is a PhD candidate who was awarded the ESRC Midlands Graduate School DTP Studentship to study at the University of Nottingham from September 2020. She is interested in improving the wellbeing and acceptance of autistic individuals, along with understanding mental health difficulties in general. She previously completed a BSc in Psychology from Royal Holloway, University of London, and an MSc in Clinical Neurodevelopmental Sciences from Kings College London.

Rebecca Lucas

Rebecca Lucas is a Senior Lecturer in Developmental Psychology at the University of Roehampton. Her research aims to understand factors influencing cognitive development and psycho-social wellbeing, primarily of individuals with developmental disorders, with emphasis on autism and developmental language disorders. She is a Fellow of the HEA.

References

- Adams, Katharine S., and Briley E. Proctor. 2010. “Adaptation to College for Students with and without Disabilities: Group Differences and Predictors.” Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability 22 (3): 166–184.

- American Psychiatric Association. 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Andrews, Gavin, Scott Henderson, and Wayne Hall. 2001. “Prevalence, Comorbidity, Disability and Service Utilisation: Overview of the Australian National Mental Health Survey.” British Journal of Psychiatry 178 (2): 145–153. doi:https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.178.2.145.

- Arnett, J. J. 2000. “Emerging Adulthood: A Theory of Development from the Late Teens Through the Twenties..” American Psychologist 55 (5): 469–480.

- Association of Graduate Careers Advisory Services (AGCAS). 2018. “A Report on the First Destinations of 2016 Disabled Graduates. Accessed 18th December 2018. What Happens Next?” https://www.agcas.org.uk/Knowledge-Centre/7991a7d5-84a0-4fe1-bbdc-5313d9039486.

- Auerbach, R. P., J. Alonso, W. G. Axinn, P. Cuijpers, D. D. Ebert, J. G. Green, I. Hwang, et al. 2016. “Mental Disorders among College Students in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys.” Psychological Medicine 46 (14): 2955–2970. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716001665.

- Ball, Charlie, Laura Greaves, Micha-Shannon Smith, and Dan Mason. 2020. What Do Graduates Do? 2020/21. Bristol, UK: Jisc & AGCAS. https://graduatemarkettrends.cdn.prismic.io/graduatemarkettrends/03ab4cc3-0da8-4125-b1c7-a877e1d5f5fd_what-do-graduates-do-202021.pdf.

- Batchelor, Rachel, Emma Pitman, Alex Sharpington, Melissa Stock, and Eilidh Cage. 2020. “Student Perspectives on Mental Health Support and Services in the UK.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 44 (4): 483–497. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2019.1579896.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2019. “Novel Insights Into Patients’ Life-Worlds: The Value of Qualitative Research.” The Lancet Psychiatry 6 (9): 720–721. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30296-2.

- Braunholtz, S., S. Davidson, K. Myant, and R. O’Connor. 2007. “Well? What Do You Think? (2006)The Third National Scottish Survey of Public Attitudes to Mental Wellbeing and Mental Health Problems.” Edinburgh: Scottish Government.

- Cage, Eilidh, Melissa Stock, Alex Sharpington, Emma Pitman, and Rachel Batchelor. 2018. “Barriers to Accessing Support for Mental Health Issues at University.” Studies in Higher Education 0 (0): 1–13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1544237.

- Christie, Fiona. 2017. “The Reporting of University League Table Employability Rankings: A Critical Review.” Journal of Education and Work 30 (4): 403–418. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2016.1224821.

- Dvořáková, Kamila, Mark T. Greenberg, and Robert W. Roeser. 2019. “On the Role of Mindfulness and Compassion Skills in Students’ Coping, Well-Being, and Development Across the Transition to College: A Conceptual Analysis.” Stress and Health 35 (2): 146–156. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2850.

- Eisenberg, Daniel, Ezra Golberstein, and Sarah E. Gollust. 2007. “Help-Seeking and Access to Mental Health Care in a University Student Population.” Medical Care 45 (7): 594–601.

- Elmer, Timon, Kieran Mepham, and Christoph Stadtfeld. 2020. “Students Under Lockdown: Comparisons of Students’ Social Networks and Mental Health Before and During the COVID-19 Crisis in Switzerland.” PLOS ONE 15 (7): e0236337. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236337.

- Eskin, Mehmet, Jian-Min Sun, Jamila Abuidhail, Kouichi Yoshimasu, Omar Kujan, Mohsen Janghorbani, Chris Flood, et al. 2016. “Suicidal Behavior and Psychological Distress in University Students: A 12-Nation Study.” Archives of Suicide Research 20 (3): 369–388. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2015.1054055.

- Essadek, Aziz, and Thomas Rabeyron. 2020. “Mental Health of French Students During the Covid-19 Pandemic.” Journal of Affective Disorders 277 (December): 392–393. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.042.

- Finn, Kirsty. 2017. “Relational Transitions, Emotional Decisions: New Directions for Theorising Graduate Employment.” Journal of Education and Work 30 (4): 419–431. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2016.1239348.

- Gewurtz, Rebecca, Sandra Moll, Jennifer M. Poole, and Karen Rebeiro Gruhl. 2016. “Qualitative Research in Mental Health and Mental Illness.” In Handbook of Qualitative Health Research for Evidence-Based Practice, edited by Karin Olson, Richard A. Young, and Izabela Z. Schultz, 203–223. Handbooks in Health, Work, and Disability. New York, NY: Springer. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-2920-7_13.

- Gillies, Jennifer. 2012. “University Graduates with a Disability: The Transition to the Workforce.” Disability Studies Quarterly 32 (3), doi:https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v32i3.3281.

- Gradel, Kathleen, and Alden J. Edson. 2009. “Putting Universal Design for Learning on the Higher Ed Agenda.” Journal of Educational Technology Systems 38 (2): 111–121. doi:https://doi.org/10.2190/ET.38.2.d.

- Grosemans, Ilke, Karin Hannes, Julie Neyens, and Eva Kyndt. 2018. “Emerging Adults Embarking on Their Careers: Job and Identity Explorations in the Transition to Work.” Youth & Society, May, 0044118X18772695. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X18772695.

- Halstead, Tammy Jane, and Douglas Lare. 2018. “An Exploration of Career Transition Self-Efficacy in Emerging Adult College Graduates.” Journal of College Student Development 59 (2): 177–191. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2018.0016.

- Hartrey, Laura, Suzanne Denieffe, and John S. G. Wells. 2017. “A Systematic Review of Barriers and Supports to the Participation of Students with Mental Health Difficulties in Higher Education.” Mental Health & Prevention 6 (June): 26–43. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhp.2017.03.002.

- HESA. 2021. “Table 15 - UK Domiciled Student Enrolments by Disability and Sex 2014/15 to 2019/20 | HESA.” 2021. https://www.hesa.ac.uk/data-and-analysis/students/table-15.

- Hillier, Ashleigh, Jody Goldstein, Lauren Tornatore, Emily Byrne, and Hannah M. Johnson. 2019. “Outcomes of a Peer Mentoring Program for University Students with Disabilities.” Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning 27 (5): 487–508. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13611267.2019.1675850.

- Holm-Hadulla, Rainer Matthias, and Asimina Koutsoukou-Argyraki. 2015. “Mental Health of Students in a Globalized World: Prevalence of Complaints and Disorders, Methods and Effectivity of Counseling, Structure of Mental Health Services for Students.” Mental Health & Prevention, Mental Health of Students – National and International Perspectives 3 (1): 1–4. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhp.2015.04.003.

- Hsieh, Hsiu-Fang, and Sarah E. Shannon. 2005. “Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis.” Qualitative Health Research 15 (9): 1277–1288. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687.

- Hughes, G., M. Panjawni, P. Tulcidas, and N. Byrom. 2018. Student Mental Health: The Role and Experiences of Academics. Oxford: Student Minds.

- Hughes, G., and L. Spanner. 2019. The University Mental Health Charter. Leeds: Student Minds.

- Kain, Suanne, Christina Chin-Newman, and Sara Smith. 2019. ““It’s All in Your Head:” Students with Psychiatric Disability Navigating the University Environment.” Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability 32 (4): 411–425.

- King, Naomi, and Louise Bunce. 2020. “Academics’ Perceptions of Students’ Motivation for Learning and Their Own Motivation for Teaching in a Marketized Higher Education Context.” British Journal of Educational Psychology 90 (3): 790–808. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12332.

- Kinman, Gail, and Fiona Jones. 2008. “A Life Beyond Work? Job Demands, Work-Life Balance, and Wellbeing in UK Academics.” Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment 17 (1–2): 41–60. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10911350802165478.

- Kitzrow, Martha Anne. 2003. “The Mental Health Needs of Today’s College Students: Challenges and Recommendations.” NASPA Journal 41 (1): 167–181. doi:https://doi.org/10.2202/1949-6605.1310.

- Kuehner, C. 2003. “Gender Differences in Unipolar Depression: An Update of Epidemiological Findings and Possible Explanations.” Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 108 (3): 163–174. doi:https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.00204.x.

- Lane, Joel. 2015. “The Imposter Phenomenon Among Emerging Adults Transitioning Into Professional Life: Developing a Grounded Theory.” Adultspan Journal 14 (2): 114–128. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/adsp.12009.

- Lavender, Anna, and Edward Watkins. 2004. “Rumination and Future Thinking in Depression.” British Journal of Clinical Psychology 43 (2): 129–142. doi:https://doi.org/10.1348/014466504323088015.

- Margrove, K. L., M. Gustowska, and L. S. Grove. 2014. “Provision of Support for Psychological Distress by University Staff, and Receptiveness to Mental Health Training.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 38 (1): 90–106. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2012.699518.

- Martin, Jennifer Marie. 2010. “Stigma and Student Mental Health in Higher Education.” Higher Education Research & Development 29 (3): 259–274. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360903470969.

- McLean, Carmen P., Anu Asnaani, Brett T. Litz, and Stefan G. Hofmann. 2011. “Gender Differences in Anxiety Disorders: Prevalence, Course of Illness, Comorbidity and Burden of Illness.” Journal of Psychiatric Research 45 (8): 1027–1035. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.03.006.

- Molesworth, Mike, Elizabeth Nixon, and Richard Scullion. 2009. “Having, Being and Higher Education: The Marketisation of the University and the Transformation of the Student Into Consumer.” Teaching in Higher Education 14 (3): 277–287. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510902898841.

- Neves, J., and N. Hillman. 2017. “2017 Student Academic Experience Survey.” York: Higher Education Academy. https://www.hepi.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/2017-Student-Academic-Experience-Survey-Final-Report.pdf.

- Nolan, Clodagh, and Claire Irene Gleeson. 2017. “The Transition to Employment: The Perspectives of Students and Graduates with Disabilities.” Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research 19 (3): 230–244. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15017419.2016.1240102.

- Olney, Marjorie F., and Karin F. Brockelman. 2005. “The Impact of Visibility of Disability and Gender on the Self-Concept of University Students with Disabilities.” Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability 18 (1): 80–91.

- Paul, Karsten I., and Klaus Moser. 2009. “Unemployment Impairs Mental Health: Meta-Analyses.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 74 (3): 264–282. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2009.01.001.

- Perrone, Lisa, and Margaret H. Vickers. 2003. “Life after Graduation as a “Very Uncomfortable World”: An Australian Case Study.” Education+Training 45 (2): 69–78. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/00400910310464044.

- Pesonen, Henri V., Mitzi Waltz, Marc Fabri, Minja Lahdelma, and Elena V. Syurina. 2020. “Students and Graduates with Autism: Perceptions of Support When Preparing for Transition from University to Work.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 0 (0): 1–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2020.1769982.

- Plutchik, R. 1991. The Emotions. Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

- Polach, Janet L. 2004. “Understanding the Experience of College Graduates During Their First Year of Employment.” Human Resource Development Quarterly 15 (1): 5–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.1084.

- Popadiuk, Natalee Elizabeth, and Nancy Marie Arthur. 2014. “Key Relationships for International Student University-to-Work Transitions.” Journal of Career Development 41 (2): 122–140. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845313481851.

- Quinn, Neil, Alistair Wilson, Gillian MacIntyre, and Teresa Tinklin. 2009. “‘People Look at you Differently’: Students’ Experience of Mental Health Support Within Higher Education.” British Journal of Guidance & Counselling 37 (4): 405–418. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03069880903161385.

- Reichert, Anika, and Rowena Jacobs. 2018. “The Impact of Waiting Time on Patient Outcomes: Evidence from Early Intervention in Psychosis Services in England.” Health Economics 27 (11): 1772–1787. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.3800.

- Richardson, John T. E. 2009. “The Academic Attainment of Students with Disabilities in UK Higher Education.” Studies in Higher Education 34 (2): 123–137. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070802596996.

- Saunders, Denise E., Gary W. Peterson, James P. Sampson, and Robert C. Reardon. 2000. “Relation of Depression and Dysfunctional Career Thinking to Career Indecision.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 56 (2): 288–298. doi:https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1999.1715.

- Savage, Matthew J., Ruth James, Daniele Magistro, James Donaldson, Laura C. Healy, Mary Nevill, and Philip J. Hennis. 2020. “Mental Health and Movement Behaviour During the COVID-19 Pandemic in UK University Students: Prospective Cohort Study.” Mental Health and Physical Activity 19 (October): 100357. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhpa.2020.100357.

- Sax, Linda J., Shannon K. Gilmartin, and Alyssa N. Bryant. 2003. “Assessing Response Rates and Nonresponse Bias in Web and Paper Surveys.” Research in Higher Education 44 (4): 409–432. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024232915870.

- Stanley, Nicky, Sharon Mallon, Jo Bell, and Jill Manthorpe. 2009. “Trapped in Transition: Findings from a UK Study of Student Suicide.” British Journal of Guidance & Counselling 37 (4): 419–433. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03069880903161427.

- Stiwne, Elinor Edvardsson, and Tomas Jungert. 2010. “Engineering Students’ Experiences of Transition from Study to Work.” Journal of Education and Work 23 (5): 417–437. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2010.515967.

- Struszczyk, Sophia, Paul Michael Galdas, and Paul Alexander Tiffin. 2019. “Men and Suicide Prevention: A Scoping Review.” Journal of Mental Health 28 (1): 80–88. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2017.1370638.

- Taberner, Andrea Mary. 2018. “The Marketisation of the English Higher Education Sector and Its Impact on Academic Staff and the Nature of Their Work.” International Journal of Organizational Analysis 26 (1): 129–152. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOA-07-2017-1198.

- Tennant, Ruth, Louise Hiller, Ruth Fishwick, Stephen Platt, Stephen Joseph, Scott Weich, Jane Parkinson, Jenny Secker, and Sarah Stewart-Brown. 2007. “The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (WEMWBS): Development and UK Validation.” Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 5 (1): 63. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-5-63.

- Tomlinson, Michael. 2017. “Student Perceptions of Themselves as ‘Consumers’ of Higher Education.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 38 (4): 450–467. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2015.1113856.

- Vanheusden, Kathleen, Cornelis L. Mulder, Jan van der Ende, Frank J. van Lenthe, Johan P. Mackenbach, and Frank C. Verhulst. 2008. “Young Adults Face Major Barriers to Seeking Help from Mental Health Services.” Patient Education and Counseling 73 (1): 97–104. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2008.05.006.

- Wang, Xiaomei, Sudeep Hegde, Changwon Son, Bruce Keller, Alec Smith, and Farzan Sasangohar. 2020. “Investigating Mental Health of US College Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Cross-Sectional Survey Study.” Journal of Medical Internet Research 22 (9): e22817. doi:https://doi.org/10.2196/22817.

- Wang, Ling, Huihui Xu, Xue Zhang, and Ping Fang. 2017. “The Relationship between Emotion Regulation Strategies and Job Search Behavior among Fourth-Year University Students.” Journal of Adolescence 59 (August): 139–147. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.06.004.