ABSTRACT

This study aimed to investigate common features and ways of understanding quality culture (QC) within higher education institutions (HEIs) in Nordic countries. While the concept of QC is commonly accepted and often used, its meaning is not always clear. This paper focuses on how Nordic universities frame QC in their internal documentation. The Nordic context was chosen due to the close cooperation on quality issues that characterise HEIs within the Nordic region. The discussion section of this paper outlines QC in relation to quality assurance (QA) among HEIs within the European and Nordic regions. Sixteen universities participated in the study by sharing documents describing their QCs. The data were analysed using qualitative content analysis and discussed from different perspectives, such as regarding how the universities use the concept of QC and how QC is created. Based on the results, a model was created that provides an overview of how QC emerges and how the concept is implemented in documentation. It is hoped that the results will both contribute useful input to the ongoing collaboration on quality issues among HEIs in the Nordic region and will also be useful in enhancing QC at universities in other regions.

Introduction

In recent decades, Europe has been working towards a common framework for understanding and assessing quality in higher education institutions (HEIs). The first European national quality assurance (QA) agencies were established in the 1990s. Since then, this work has been closely connected to consolidating the European Higher Education Area (EHEA) as part of the Bologna Process. Among other results of the EHEA’s work, Standards and Guidelines for Quality Assurance in the European Higher Education Area (ESG, Citation2005, 2015) have been developed. According to these guidelines, QA activities share the dual, interrelated aims of promoting accountability and enhancement in higher education. Furthermore, the guidelines advise that universities should not only develop QA systems but also enhance their quality cultures (QCs).

The authors have had the privilege of participating in QA work and evaluating the quality systems of universities in the Nordic countries (i.e. Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden). In this context, the question of how QC can be defined, implemented and evaluated has arisen regularly. While the concept of QC is commonly accepted and often used, its meaning remains unclear in quality documentation. One reason for this might be that QC is something that must be crafted to suit each individual university and based on each university's unique definition. OC is not a concept that can be defined in specific terms across the higher education domain in general. This also leads to uncertainty about whether and how QC can be evaluated. Theoretical research in this specific problem area is sparse. The research and reports that currently exist in this field are largely about quality and QA processes in HEIs (e.g. European University Association, EUA Citation2006; Ehlers Citation2009; Sursock Citation2011), discussions about QC as a concept (e.g. Harvey and Stensaker Citation2008; Persson Citation1997) or how universities reflect on quality (e.g. Harvey and Green Citation1993; Harvey Citation2006; Elken and Stensaker Citation2018; Schindler et al. Citation2015; Njiro Citation2016).

The study presented in this article investigates how the universities frame their QCs and its aim is to achieve a better understanding of how Nordic universities think about QC. The analysis is based on documents that the universities chose to send to the research team as material describing the universities’ QCs. The research question is: Are there common features and ways of framing QC within HEIs in the Nordic countries, and if they exist, what are they? The delimited regional area within the zone of European cooperation was chosen because the Nordic countries share a mostly enhancement-led approach to QA and an understanding of higher education as a public good, and they have a high level of academic autonomy.

Quality and quality assurance in higher education institutions

Defining quality and QA in the context of HEIs continues to be challenging. A review of the literature confirms that HEIs define ‘quality’ in different ways (e.g. Harvey and Green Citation1993; Harvey Citation2006; Elken and Stensaker Citation2018). Schindler et al. (Citation2015; Njiro Citation2016) identify four different meanings of ‘quality’; purposeful, exceptional, transformative and accountable. They emphasise that the definition of quality depends on the perspective from which it is investigated (i.e. the educators’, students’ or administrators’ perspectives). Definitions also have different foci; they can focus on processes, policies or actions, or on accountability and/or continuous improvement (Schindler et al. Citation2015).

In recent decades, as HEIs have become more globalised, further development of how quality and QA are defined and measured has been required. Universities need to demonstrate, both nationally and internationally, that their activities are of high quality. The European and Nordic co-operation on quality among HEIs has provided one response to this need. The European Quality Assurance Network in Higher Education (ENQA) was established in 2000, and the Nordic Quality Assurance Network (NOQA) was formalised in 2003 (Wächter et al. Citation2015). These networks provide independent information on how HEIs can succeed in adhering to the different defined standards of good quality and contribute to confidence in HEIs. QA has also been at the heart of the Bologna Process. In 2003, member countries agreed on a common framework for national QA systems (Berlin Communique Citation2003). In 2005, the first edition of the Standards and Guidelines for Quality Assurance in the European Higher Education Area was approved by the European ministers of education (a revised version in 2015). The Nordic region has been actively involved in European QA work in HEIs.

When discussing the work undertaken towards achieving quality and/or QA in HEIs, it is possible to discuss this topic from at least two perspectives: an external and/or an internal perspective. The external perspective is here understood as quality enhancement and evaluation of the quality of HEIs’ work carried out by external organisations, groups or persons according to national or international guidelines for the evaluation of quality. The internal perspective refers to the evaluative activities that take place within the organisation itself – its perception of good quality and its methods of evaluation and assurance.

Ehlers (Citation2009) states that the external perspective may be perceived as characteristic of former HEI eras, while the internal perspective better describes the modern HEI perspective. The previous or traditional understanding of organisational management is based on the belief that one can accurately plan and predetermine activities and that quality can be achieved by adhering to such preordained strategies. Ehlers (Citation2009) states that quality cannot be predefined by experts; rather, it is a result of collaboration and open discussion, and it is in everyone's interest to contribute to achieving quality in HEIs. According to Sursock (Citation2011), institutional autonomy and self-confidence are key factors in HEIs’ quality work. Therefore, it is crucial that internal QA processes are in line with universities’ respective profiles, strategies and organisational cultures.

Another aspect of quality in the HEI context is internal control, which, according to Feng, Li, and McVay (Citation2009), provides the basis for creating and maintaining a stable and reliable organisation. The purpose of internal governance and control is to be able to state, with reasonable certainty, that the university fulfils its goals and responsibilities and conducts operations in accordance with the relevant authority's requirements for efficiency, compliance with regulations, reliable accounting and good housekeeping of allocated resources. As universities’ risk analysis is a key element in achieving these goals, internal control may be included in their QA systems.

Thus, the concept of quality in the HEI domain is multidimensional and, according to Persson (Citation1997), includes scientific, educational, financial–administrative and social dimensions. Quality in scientific areas is related to how well HEIs’ educational content corresponds to the wider scientific domain. Educational quality is related to pedagogical factors, such as student learning outcomes and teaching quality. Finally, financial-administrative quality is related to how resources are distributed and used within an organisation, while social quality concerns the social relationships that the university promotes and organises.

Loukkola and Zhang (Citation2010) note that the work to develop and ensure quality in HEIs in relation to the European guidelines has continued at individual universities and that QA processes are carried out and evaluated. Nevertheless, there is little research on how European universities have succeeded in developing QC.

The concept of quality culture

The interest in QC in the world of HEIs has mostly emerged during the last two decades. The term ‘QC’ was introduced in HEIs to clarify the notion that the culture of an organisation and its educational quality should not be regarded as independent entities; rather, ‘quality stems from a broader cultural perspective’ (Harvey and Stensaker Citation2008, 431). According to Harvey and Stensaker (Citation2008, 433), the ‘QC project’ related to the Bologna process in the early 2000s was intended ‘to increase awareness of the need to develop an internal quality culture in universities and aid wide dissemination of existing best practices in the field’. The project aimed to introduce internal quality management to universities and help them develop external QA procedures. The political aim was to strengthen global interest in European universities.

Harvey and Stensaker (Citation2008) imply that there may also have been an assumption that the way in which QC is developed is transferable from one institution to another. However, the European University Association (EUA Citation2006, 10) emphasises that it is the individual institution's responsibility to describe its QC and that a common definition is not possible or desirable. According to the EUA's definition, QC is ‘shared values, beliefs, expectations and commitments toward quality’ and ‘a structural/managerial element with defined processes that enhance quality and aim at coordinating efforts’ (EUA Citation2006, 10). QC represents a specific kind of organisational subculture that overlaps with other subcultures based on the shared values of its members. Leadership is an organisational element that ‘binds’ the structural/managerial and cultural/psychological elements by creating trust and shared understanding. Communication serves as a secondary organisational binding element (Bendermacher et al. Citation2017). Loukkola and Zhang (Citation2010, 12) report that ‘Quality Culture is closely related to organisational culture and firmly based on shared values, beliefs, expectations and a commitment towards quality, dimensions which make it a difficult concept to manage’. Ehlers (Citation2009, 3) states that ‘quality culture as such focuses on organisations’ cultural patterns, like rituals, beliefs, values and everyday procedures while following processes, rules and regulations’. A university's QC is reflected in how university staff discuss and address the issue of quality in their everyday work-related practices. When defining an organisation's QC, it is therefore crucial to consider how individuals are involved in the organisation's social context. This also includes group controls and external rules that regulate individual behaviours within the organisation.

Despite the existing definitions of QC and active cooperation regarding quality-related issues among HEIs, the understanding of QC in the HEI domain remains unclear (Bendermacher et al. Citation2017). Universities do not necessarily spend much time reflecting on the nature of QC. This becomes especially clear during an external evaluation of HEIs’ QA systems. This is not to say that any universities believe that QC is insignificant; on the contrary, a reason for this ambiguity may be that universities have focused so intensely on internal QA that it has become synonymous with QC (Berings Citation2009; Berings et al. Citation2010). Another reason may be that QC is so entrenched in the structure of the organisation that it is taken for granted and not discussed (cf. Harvey and Stensaker Citation2008).

Harvey (Citation2010) criticises the first 20 years of QA in the HEI domain as a largely administrative exercise focused on procedures and internal assurance mechanisms. Elken and Stensaker (Citation2018) broaden the discussion and note that HEIs tend to try to improve quality in two ways: some institutions develop internal quality management systems with formal organisational rules and routines, while others focus on creating a QC based on a broader commitment to quality and improvement. With a focus only on externally evaluated processes, improvement may take place in the short term, but as soon as an HEI's motivation cools down, its improvement work may also slow down (Kis Citation2005). The interaction between ongoing internal quality work and external monitoring is therefore important.

Additionally, Vettori and Rammel (Citation2014) state that while QC cannot be implemented from above, strong leadership is necessary for starting and promoting the process. Thus, success factors for effectively generating QC include the capacity of the institutional leadership to provide room for a grassroots approach to quality (involving wide consultation and discussion) and to avoid the risk of over-bureaucratisation (EUA Citation2006). Generally, the interplay between, on the one hand, manifest and formal QA processes and, on the other hand, latent and informal values and assumptions is at the heart of enhancing institutional QC (Vettori Citation2012).

Harvey and Stensaker (Citation2008, 13) posit that ‘quality culture is nothing if the people who live it do not own it’. Similarly, Njiro (Citation2016, 81) states that ‘high quality education is not a product of only formal quality assurance processes, but it is rather a consequence of a quality culture shared by all members of an institution’. Njiro (Citation2016) emphasises that culture is not homogeneous but reflects an organisation's internal complexity. Vettori and Rammel (Citation2014) also propose that the basic principles of QC must be largely shared or at least accepted by the whole organisation. Sursock (Citation2011) concludes that QA tools and processes contribute to universities’ QC in the following ways:

The factors that promote effective quality cultures are that: the university is located in an ‘open’ environment that is not overly regulated and enjoys a high level of public trust; the university is self-confident and does not limit itself to definitions of quality processes set by its national QA agency; the institutional culture stresses democracy and debate and values the voice of students and staff equally; the definition of academic professional roles stresses good teaching rather than only academic expertise and research strength; quality assurance processes are grounded in academic values while giving due attention to the necessary administrative processes. (Sursock Citation2011, 10)

The research

The discussion about HEIs’ QC is not new. Nevertheless, it is important to explore how universities in the Nordic countries describe and deal with QC and whether these universities conceptualise it in a similar way. The Nordic countries have a similar educational history, educational culture and educational systems. All Nordic countries are members of the EUA, and their national QA systems and evaluation models are in line with the ESG. Experts in Nordic countries are often involved in neighbouring countries’ QA work and reviews. Knowledge about how universities in the Nordic region view QC may further develop Nordic cooperation. Despite their many similarities, Nordic universities also have many differences and thus form an interesting object for research. It is important to emphasise that the aim of the study was not to evaluate the universities’ QCs nor to compare countries or universities; rather, it aimed to investigate whether there are common features and ways of thinking about QC among HEIs in Nordic countries.

Data collection

There are over 80 HEIs within the Nordic region. The study aimed to sample data from a breadth of different kinds of universities, but it was not possible to integrate all 80. The researchers systematically analysed the HEIs in the Nordic region by reviewing the universities’ websites to collect a sample that provides a broad view of QC and represent all Nordic countries as evenly as possible. Specific requirements were placed on the data: 1) a breadth of older and younger universities; 2) universities with at least three fields of science; and 3) universities with both bachelor's, master's and doctoral programmes. In relation to the requirements 20 universities were chosen.

In December 2020, invitation letters were sent to the universities. Four invitation letters were sent to universities in Denmark, four were sent to universities in Finland, five were sent to universities in Sweden, five were sent to universities in Norway and two were sent to universities in Iceland. Sixteen universities agreed to take part in the investigation (see ). The HEIs were founded between the fifteenth century and the beginning of the twenty-first century, and all 16 universities offer education at all three levels of study and represent at least three fields of science.

Table 1. Presentation of university sample and compilation of data material and basic documents

The invitation letters were sent to the universities’ registrars and the vice-rectors responsible for quality. The recipients were chosen based on the fact that the vice-rector plays a central role in the university's quality work. This could have led to receipt of a narrow set of documents, but most of the vice-rectors involved quality coordinators and other quality managers in the delivery process, which can be seen in the diversity of material submitted to this study.

In the invitation letter, the universities were asked to send ‘the description of the university's quality culture or documents that the university thinks describe the quality culture of the university’. The researchers did not wish to specify exactly which material the universities should deliver to ensure that the universities themselves decided which material best describes their QC. The material that the universities delivered to the research group is summarised in . In total, 69 different types of documents were sent to the research group.

The characteristics of the documents differ, and they were most likely written for different audiences (cf. Schindler et al. Citation2015; Njiro Citation2016). It is also conceivable that some universities may have perceived the assignment as a way of marketing themselves, others perhaps as an evaluation or even as a control of their quality work and quality system. A discussion of the focus of the study may have led to further documents. The universities might even have wanted to prepare new specific documents. However, the researchers did not want to influence the universities. Instead, we wanted to receive the existing materials that the university is currently using to describe its QC—documents that reflect the current reasoning related to QC at the university. The materials could be documents that have resulted from a decision-making process or other types of material. What the universities chose to send to the researchers was perceived as their choice of documents to describe their QC.

In the analysis and discussion of the results, the material was treated as comprehensive data. The reason for this is that the aim of this study was not to compare individual universities or countries but to capture the different aspects and features of understanding QC in Nordic universities. Because of this, the universities were promised that their names would not be mentioned in the article, except to indicate that they were HEIs that supplied material to the study.

Methods

This study adopted a qualitative research approach. The data were analysed using qualitative content analysis (Elo and Kyngäs Citation2007; Mayring Citation2014) to identify patterns of common features and content in the universities’ descriptions of their QCs. Thus, the analysis focused on the text in the documents that described the universities’ QCs. The data were analysed by identifying keywords and variations, which were then categorised according to common themes. Of special interest were texts that dealt primarily with ‘quality culture’ and, secondarily, ‘quality’ and/or ‘culture’. Descriptions that did not use these terms were omitted from the analysis to avoid overinterpretation. Nevertheless, it can be stated that even the analysis of text in relation to the given concepts included unavoidable interpretations of what the universities mean. Researchers’ focus and interpretation may have affected the results. To guarantee the reliability of the analysis and the conclusions, the researchers analysed the material in several rounds, both individually and as a group. This helped the members of the research group recognise and understand interpretations of themes based on their own analyses, which increased reliability. Conflicts of interest were avoided, as everyone in the research group participated in all steps of the analysis and the formulation of the results.

In the first stage of the analysis, the universities’ documents were analysed in relation to the following six questions: 1) How do Nordic universities describe their QC? 2) How do Nordic universities deal with QC? 3) How do Nordic universities describe that QC is created? 4) How do Nordic universities describe that QC can be led and safeguarded? 5) How do Nordic universities describe the relationship between QA and QC? 6) How do Nordic universities reflect on QC and internal control? This stage of the analysis continued until no new categories could be identified. In the second stage, the categories were combined into perspectives, and in the third stage, the perspectives were combined into overall descriptions (see an example in ). In this way, comprehensive information on how the universities think about QC was made visible so that it could be used in the discussion of the results.

Table 2. . An example of an analysis in process.

Results

The summary in shows the 25 overall descriptions originating from the material, along with the six questions asked when reviewing the material. The overall descriptions are discussed in this section under the following sub-sections: Descriptions of and Dealing with Quality Culture (questions 1–2); Creation and Management of Quality Culture (questions 3–4); and Evaluation and Assessment of Quality Culture (questions 5–6).

Table 3. The overall descriptions that emerged from the data

Descriptions of and Dealing with Quality Culture

The descriptions of QC among the Nordic universities participating in this study vary. On the one hand, the variations are clear and descriptive; on the other hand, there is apparent evidence that the universities do not have a well-defined description of their respective QCs. Also, there is evidence that the universities describe their respective QCs with some caution. Nevertheless, four consistent description themes emerged from the data: structured and systematic; integrated and well-known; trust, engagement and participation; and active through personal responsibility.

The universities’ QCs appear to be based on values related to their respective countries’ national and current contexts, as well as their respective heritages and traditions. Furthermore, the most valuable components of QCs are believed to be relationships and collaboration. One important strategy for QA is ensuring that research and degree courses meet national and international criteria and quality requirements, which form an essential basis for public trust in universities. QC within the universities appears to be strongly related to and based on shared values, clear strategies, systematic planning, performance reviews based on reliable information and continuous improvement. To ensure and improve the universities’ QCs, it appears to be essential that tools and processes are in place to define, measure and evaluate QC. QC is described as a network of systematic and continuous processes that are actively maintained, continuously reviewed and renewed. Other important aspects of QC include transparency in organisational processes, communicating QA and QC in open dialogues at different levels in the universities and showing care for students, staff and society.

It also appears that the development and management of the programmes must be integrated into each university's organisation and rooted at the highest management level. Furthermore, it is vital that the QA system is well understood by everyone, including management, teachers, students, other employees at the university and external stakeholders. Active students play an especially important role in QC. In terms of personal accountability, the following factors were highlighted in the results: responsibility, trust, engagement, respect and participation. According to the material, personal accountability is an essential prerequisite for creating robust QC and developing it further. QC can be described as an approach based on everyone's engagement, trust and responsibility. When management, teachers and students live up to their responsibilities by contributing to HEIs’ QA work, the effectiveness of the institution's QC is supported and enhanced. Achieving this requires integrated efforts at all levels of universities.

The analysis of the material highlights five different ways of dealing with QC (see ). The term QC is used to highlight and describe the quality of a university's activities from a general perspective. Here, QC is described as the goal of the organisation's quality-related activities or as the tool for the university's qualitative work; for example, QC might be described as values that the university wants to support through its quality-related work. This is realised in systematic QA work and decided upon by management or defined in the universities’ strategies. In some documents, QC is used in the same sense as the organisational culture of the university. In these cases, the universities highlight that all stakeholders share common values. QC is also used as a synonym for the term quality and to describe good quality in the implementation of university activities (teaching, research, and/or administration). It is important to mention that there are also universities that choose not to use the concept of QC. Nevertheless, in their cover letters to the researchers, such universities reported that the documents described their QCs. When analysing these documents, while manifold uses of the concepts of culture or quality emerged, the concept of QC did not. This gives an indication that the concept of QC is perceived as ambiguous or difficult to define and that universities therefore avoid using it. It may also be the case that the concept has simply not been kept in mind when designing documents.

Creation and management of quality culture

The analysis shows that universities create and develop their QCs through action. Universities demonstrate different ways of sustaining or creating QC in their organisations. This result suggests that there is no simple recipe for developing QC. It is also challenging to convey a clear description of the roles of individual stakeholders and the distribution of responsibilities in implementing or sustaining a QC. Therefore, it appears that QC cannot be adopted from other contexts or organisations; it can only be crafted by the organisation that wishes to implement it. HEIs describe their expectations of academic communities and management regarding the creation or development of the QC. Specifically, our data shows that their main expectation is shared responsibility founded in a common set of values, perceptions and expectations.

Based on the analysis of the data, QC is created at a strategic level through planning documents, an institution's strategies and governing bodies. The development of a QC is outlined and formalised as a top-down process. The message of such processes is materialised through external requirements, processes and responsibilities that are related to a formal framework, administrative performance requirements and management via formal governing bodies. Such centrally defined frameworks, interventions and strategies form the basis of a common QA system with the potential for adaptation at different university levels.

All employees and students have a responsibility to cultivate and support QC based on their university's values. Faculty boards are tasked with monitoring the faculty's development in terms of ensuring quality in education, research and associated collaborations. When the foundation for the QC is set, it is the responsibility of leadership at different levels of the university to contribute to the QC; that is, QC is created through management. A focus is on visible leadership, stability and resilience over time. Responsibility for an academic area always includes responsibility for quality-related work in the HEI context.

The data suggest that QC is also created through interpersonal relationships. It is important to understand that achieving QC goals requires honesty, openness and trust and that difficult topics can and must be discussed in an equal dialogue. One example of this is the feedback provided to study boards and study leaders by student representatives and institute councils. Furthermore, the data reveal that QC is created through development work. This may indicate that institutions take feedback seriously; it contributes to improvements in quality and is important for success in achieving quality. In this, diversity and, at the same time, systematics are described as crucial resources in quality-related work. Stakeholders realise that through diversity-led practices, existing assumptions and obvious truths can be challenged. The credibility of a diversity-focused approach is described as a quality system that applies to all HEI activities (i.e. for quality work in education, research, and operational and management support). Finally, the data show that QC is created through information and dissemination. The material shows that dissemination of the institution's message must take place via digital infrastructure, dialogue-based meeting places, and easily understandable information that is tailored to specific target groups, such as students, staff and external stakeholders. A crucial element of QA in education is its capacity to maintain a constant dialogue about the development of programs. The evaluation of education must create legitimacy and provide information to external individuals and organisations about the quality of the education offered by an institution.

Thus, the material provided by the universities describes three perspectives on how QC can be created, led and safeguarded. The main perspectives can be defined as top-down, bottom-up and top-down/bottom-up perspectives. From a top-down perspective, the universities describe how their management groups lead their quality work and assume responsibility for their respective QCs. Through the strategy work and systematic quality work described in the guidelines for their QA systems, the data show that management both leads and protects the QCs of the sampled universities. The universities describe how their QC has emerged and developed through, for example, openness and cooperation and how it is cherished by all university stakeholders. Also, maintaining open communication and an atmosphere of dialogue are mentioned as central tools for achieving this. This approach to leading and safeguarding QC can be defined as a bottom-up perspective. The top-down/bottom-up perspective is a combination of both perspectives. Such HEIs describe how their QC is created, led and safeguarded by alternating between cooperating with the initiatives and responsibilities of their university's management group and cooperating with the initiatives and responsibilities of everyone else at the university.

Evaluation and assessment of quality culture

Different ways of understanding QC and its position in relation to quality and management systems affect management attitudes towards the evaluation of QC. In the data, there are very few direct references to the evaluation or assessment of QC specifically. In general, universities state that QC must be actively maintained and continuously reviewed as part of their institutional QA system and/or that QC must be shared and owned by the entire academic community. Each member of the university community plays a role in the QA system and ensures that QC is upheld. The level of engagement and ownership can be evaluated through a range of surveys or internal reviews. However, the data still reflect the different perspectives that exist among the universities.

One way to refer to evaluation and assessment of QC is that they are coinciding. In this context, it is tempting to note that the description of QA processes does not have any significance in practice. However, evaluating the relationship between theory and practice falls outside the scope of this study. What is significant for this study is that universities perceive QA processes as coinciding with QC.

Another way is to state that the QA and enhancement system is based on the existing culture of academic quality. QC is presented as an overall understanding that also includes tools and processes for defining, evaluating, ensuring and improving quality. For follow-up, universities use the plan-do-check-act (PDCA) circle of continuous improvement. The mere existence of QC is not enough to guarantee good quality-related work; it must be followed up on.

A third way of describing evaluation and assessment of QC is the opposite of the latter. Universities see that QA and its processes are used to develop the universities’ QCs. Thus, the goal of QA and the quality management system is to assist with creating a shared culture and quality-led institutional practices. Some universities describe the mutual dependency of different ‘quality issues’ as circles inside each other, where the inner circle is constituted by QC and the outer circles comprise quality management, the quality system and quality policy development. The main principles of QA are formulated, for example, in the universities’ respective strategies and developed into measurable actions in their quality work, which again promotes QC. In these cases, the discussion of QC is contained in the documents under the theme of systematic external reviews (national QA models).

The data show that at many universities, internal control is included in the university's QA system. Quality documents are reviewed regularly, both collegially and by internal and external audits. Organisationally, internal control has an overall function at the university, including quality work. There is a relationship between QC and control and monitoring functions. To achieve credible QC, the control and monitoring functions must be clear and functional. Thus, internal control is described as a top-down mechanism that controls universities’ finances and management-related activities. Universities must function legally, cost effectively and influentially. Internal control is also described as dependent on bottom-up activities that are enacted via the institutions’ risk management work.

Discussion

At first glance, the results highlight the complexity of QC and the lack of common ways of understanding QC within HEIs in Nordic countries. At the same time, the findings reveal several commonalities among HEIs with respect to QC. As it is not the aim of this study to discuss the differences between the sampled Nordic universities, we concentrate on the main common features we identified.

First, when the universities were asked to send us documents describing their QC, they either sent key documents that describe their institutional strategy and/or QA system or documents focusing on a more practical description of their QC and quality work. This can be interpreted as representing two extremes of how universities understand QC: 1) an understanding based on key documents concerning strategy and QA and 2) an understanding based on ongoing activities at the university (cf. Ehlers Citation2009; Sursock Citation2011). This finding suggests that the management of QC at the universities is either top-down or bottom-up; key documents, such as those regarding strategies and QA systems that are decided upon at the management level, have a top-down perspective, while documents that describe the university's QC based on practical everyday activities have a bottom-up perspective. The documents also describe interactions between the top-down and bottom-up approaches in which QC development is a result of dialectic processes (cf. Berings Citation2009). Thus, QC can be created and maintained partly through strategy, systematic processes and tools, and internal control, and partly through an open climate in which communication and dialogue are cherished (cf. Bendermacher et al. Citation2017; Feng, Li, and McVay Citation2009; Sursock Citation2011; Vettori Citation2012; Vettori and Rammel Citation2014). This also applies to the evaluation of QC. It takes place either through top-down external auditing/accreditation processes or through internal follow-up that is integrated into the implementation of QC activities (cf. Ehlers Citation2009).

Another interesting finding is the differing definitions of QC among universities. Universities define their QCs in their documents by referring to the definitions of the concept provided by national QA agencies or international guidelines (e.g. EUA Citation2006; ESG, 2015) or by referring to the university's values, traditions and heritage (cf. Harvey and Stensaker Citation2008). When the former is the case, QC can be described in general terms; however, when the latter is the case, QC is viewed as a specific aspect of the individual university. It is important to note that there are also universities that do not use the concept of QC in their documents. Some reasons for this might be that the concept of QC is perceived as overly complex or ambiguous, or that there are several QCs at the university and it is therefore difficult to describe QC in institutional documents. This could also mean that QC is already so fully integrated into the organisation that there is no need to put it into words (cf. Harvey and Stensaker Citation2008; Berings Citation2009; Berings et al. Citation2010; Njiro Citation2016; Schindler et al. Citation2015; Bendermacher et al. Citation2017; Elken and Stensaker Citation2018). However, in the cover letters accompanying the submitted documents, the universities emphasise that the documents they provide describe their QC.

Third, the importance of interpersonal cooperation, trust, shared responsibility, an open climate and communication, and information sharing were found to be common themes. In the sampled universities, each respective QC is created by everyone responsible for ensuring good quality in the university's operations. Taking on this responsibility, in turn, appears to be based on the belief that the staff and the students are trusted, their commitment is appreciated and they can participate in the university's various activities (cf. Ehlers Citation2009; Loukkola and Zhang Citation2010; Bendermacher et al. Citation2017). These values are highlighted both in documents that define QC in specific terms and in those that do not define QC specifically. The difference is that, in the first case, the defined or described QC is linked to the goal of the quality work undertaken by the respective universities.

Conclusion

The research question in this study was whether there are common features and ways of reasoning about QC within HEIs in Nordic countries. The conclusions drawn are considered representative of Nordic universities because the sample was selected to represent the universities in the Nordic region.

Our research findings support previous research showing that QC is a concept difficult to handle for the universities. The findings reveal that the QC-related documents at Nordic universities have differing definitional perspectives on QC, differing views on the responsibilities and leadership required for QC and differing views on the systems, structures, evaluation and control of QC. The findings also align with reports and guidelines on how QC can be described, formed, led and evaluated. Some definitions of QC can even be derived directly from national or international guidelines for QA in HEIs.

Nevertheless, there are some common features in the descriptions of QC among Nordic universities. They largely mention (either defined or undefined) QC in formal key documents, such as those related to the university's strategy or describing their QA system and/or internal control system. The findings also demonstrate that QC is created and maintained, on the one hand, through systematic processes and tools and, on the other hand, by a climate of open communication, as well as values such as cooperation, trust, participation and engagement. The interplay between manifest QA processes and latent and informal values and assumptions is at the heart of enhancing QC.

At Nordic universities, QC may be described and led by management, but everyone is responsible for it. This approach is based on the university's staff and students feeling that they can be responsible, gain trust, feel appreciated for their commitment and participate in the university's various QC activities. Finally, the results show that QC at Nordic universities tends to be evaluated via external and internal quality processes.

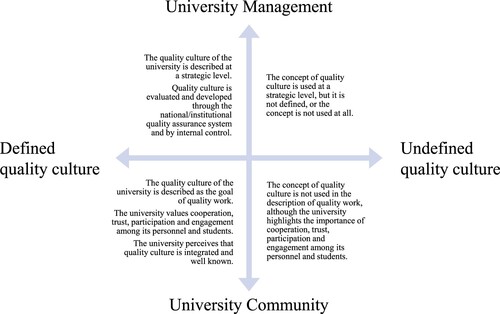

Based on a comprehensive overview of the results, a model (in ) was created to illustrate the characteristics of how the Nordic universities’ frame their QCs in the documents provided to us. The presented model was created to answer the research question. The model shows the areas (types) of emphasis that are evident in the themes derived from the universities’ documents.

The model is formed by two opposing areas that can be identified in the material: 1) there is a distinct difference between documents defining QC and those not defining it, and 2) there is also a difference between how the responsibility for and management of the universities’ QC is described in the documentation; specifically, it is either described as the responsibility of management or as a responsibility undertaken by all members of the university community (staff, students and stakeholders). The arrows show that movement between the areas can occur; a university's QC-related documents can move between the areas depending on their purpose and target group.

The area in the upper-left corner of the model is labelled as defined QC/university management. This type of description of a university's QC is characterised by its ostensive definition in the university's documents and strategies, for which management is responsible. Such descriptions are based on a general definition of QC in the university's strategies and/or in its QA systems. These descriptions are connected to the university's values, traditions and heritage. These universities also refer to the defined QC in the documents that describe their respective internal quality processes and examples of their quality work and in other applicable documents.

The universities’ defined QC also permeates the area in the lower-left corner of the model, which is labelled as defined QC/university community. The characteristic feature of this type of description is that QC is described as the goal of an institution's activities. Here, QC is described as integrated and well understood across all university activities and by all stakeholders. The basis for this type of description of QC is that the university values cooperation, trust, participation and engagement among its personnel, students and other stakeholders.

If the concept of QC remains undefined or unused, internal documents on quality work are unrelated to the development of QC. This type of relationship to QC is described as an undefined QC/university community in the lower right corner of the model. In this case, values such as shared responsibility, cooperation, trust, participation and engagement among personnel and students are highlighted in the university's documents, but the concept of QC is not used.

The fourth and final type of approach to QC is undefined QC/university management. This category is found in the upper-right corner of the model, and it represents cases in which the concept of QC is used but remains undefined or cases in which the concept is not used at all. In these cases, the quality-related work of the university is described in its key documents, such as those regarding strategies or its QA system, but without tying it to the university's QC.

It should be noted that the model is created as a typology to highlight areas that the documentation describes and covers. The model does not describe individual universities’ QCs. For those who are interested in quantitative assessments, it can be stated that the overall focus of the documents that the universities sent to the research group is interpreted as being related to the field of ‘defined/university management’. However, many universities have delivered documents that can be attributed to several or all areas of the model. The model may help initiate further discussion at universities on how to nurture QC and how to describe/present it.

It may be stated that the results of this study are based on documents produced by Nordic universities. However, as the results are in line with and clarify former research on QC, they may also be useful in a broader context. For this reason, a future project could involve carrying out comparative research in another part of the world. However, even the model presented in this study may be useful in supporting work towards implementing and/or enhancing QC at universities in other regions, although it primarily contributes to the ongoing collaboration on QC issues in HEIs in the Nordic region.

Acknowledgements

The research group thanks the universities that, in a collaborative way, contributed material to the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Christina Nygren-Landgärds

Christina Nygren-Landgärds, is a professor in education at both University of Agder (UiA) in Norway and Åbo Akademi University (ÅAU) in Finland. For almost 15 years, she was the dean and later the vice rector at the ÅAU. During this time, she deepened her interest in questions concerning organizational culture and quality culture. Nygren-Landgärds has participated in several external audits of HEI's quality assurance, mainly in Sweden, and is a member of the Evaluation Council of the Finnish Education Evaluation Centre (FINHEEC). At ÅAU she is responsible for the scientific field of education within the teacher education programs at bachelor's, master's, and doctoral level. At UiA she is responsible for the scientific field of university pedagogy and competence-enhancing pedagogical education for university employees.

Lena B. Mårtensson

Lena B. Mårtensson is currently employed at the University of Skövde, Sweden. Since 2013 she has held the position as pro-vice-chancellor. She is also an adjunct professor at the University of Queensland, Australia. Her research field of interest includes midwifery, pain, non-pharmacological pain relief, pain assessment, randomized controlled trials, and qualitative research. Since 2013 she has been involved in several groups within the Swedish Higher education Authority, evaluating midwifery educational programs, evaluating application for two doctoral programs in caring science and higher education quality assurance processes. She is also a member of the National Council for Competence in Healthcare on behalf of the Government.

Riitta Pyykkö

Riitta Pyykkö, Professor Emerita of Russian Studies, former Vice Rector of the University of Turku, Finland (2012-2019). Active in the development of higher education at national, Nordic and European levels. In 2008-2014, Chair of the Finnish national quality assurance agency FINHEEC. Member of the Finnish Bologna Promoters’/Experts’ Team in 2006–2013 and member and chair of several other national working groups and projects. In 2016-2020, member of the European University Association's Learning and Teaching Steering Committee, from 2017, member of the Register Committee of the European Quality Assurance Register for Higher Education (EQAR).

John Olav Bjørnestad

John Olav Bjørnestad is the Director of the Center for Teaching and Learning at the University of Agder. He is on leave from a position as Associate Professor at the Department of Psychosocial Health at the same university. His research is focusing on aims as moral development and health coaching. As a director, he is involved in issues related to leadership, quality issues and other university issues.

Roald von Schoultz

Roald von Schoultz, Master of Economics, was the internal auditor at Åbo Akademi University (2015-2021). Within his assignment he collaborated with the university's board and the university's management. Von Schoultz's area of responsibility was issues of internal control, quality assurance and risk management. He has recently moved on and is nowadays the CEO of an energy company in Finland.

References

- Bendermacher, G.W.G., M.G.A. Oude Egbrink, I.H.A.P. Wolfhagen, and D.H.J.M. Dolmans. 2017. ‘Unravelling Quality Culture in Higher Education: A Realist Review.’ Higher Education, 73(1): 39–60. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs10734-015-9979-2. doi: 10.1007/s10734-015-9979-2

- Berings, D. 2009. Reflection on Quality Culture as a Substantial Element of Quality Management in Higher Education. Brussel: Hogeschool-Universiteit Brussel. http://www.aic.lv/bolona/2010/Sem09-10/EUA_QUA_forum4/III.7_-_Berings.pdf.

- Berings, D., Z. Beerten, V. Hulpiau, and P. Verhesschen. 2010. ‘Quality Culture in Higher Education: From Theory to Practice.’ In Blättler, A. (Ed.) Building Bridges: Making Sense of Quality Assurance in European, National, and Institutional Contexts. A Selection of Papers from the 5th European Quality Assurance Forum. November 18–20, 2010. EUA Case Studies. France: University Claude Bernard Lyon 1: 38–49. https://eua.eu/downloads/publications/eqaf2010_publication.pdf.

- Berlin communiqué. . 2003. Realising the European Higher Education Area. Communiqué of the Conference of Ministers responsible for Higher Education in Berlin on 19 September 2003. https://www.moveonnet.eu/institutions/documents/bologna/berlin_communique.pdf/view.

- Danmarks akkrediteringsinstitution. 2019. Vejledning om institutionsakkreditering. [Guidance on institutional accreditation.] København: Danmarks akkrediteringsinstitution. https://akkr.dk/wp-content/filer/akkr/Vejledning-om-institutionsakkreditering_2_0_web.pdf.

- Ehlers, U.-D. 2009. “Understanding Quality Culture.” Quality Assurance in Education 17 (4): 343–363. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235305231_Understanding_quality_culture. doi: 10.1108/09684880910992322

- Elken, M., and B. Stensaker. 2018. “Conceptualising “Quality Work” in Higher Education.” Quality in Higher Education 24 (3): 189–202. doi:10.1080/13538322.2018.1554782.

- Elo, S., and H. Kyngäs. 2007. “The Qualitative Content Analysis Process.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 62: 107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

- European University Association (EUA). . 2006. Quality culture in European universities: a bottom-up approach. https://eua.eu/resources/publications/656:quality-culture-in-european-universities-a-bottom-up-approach.html.

- Feng, M., C. Li, and S. McVay. 2009. “Internal Control and Management Guidance.” Journal of Accounting and Economics 48 (2–3): 190–209. doi:10.1016/j.jacceco.2009.09.004.

- Finnish Education Evaluation Centre. 2019a. Audit manual for higher education institutions 2019–2024. FINEEC Publications, 21: 2019. https://karvi.fi/app/uploads/2019/09/FINEEC_Audit-manual-for-higher-education-institutions_2019-2024_FINAL.pdf.

- Finnish Education Evaluation Centre. 2019b. FINEEC’s shared evaluation and quality management concepts. https://karvi.fi/en/fineec/support-for-quality-management/fineecs-evaluation-and-quality-management-concepts/.

- Harvey, L. 2006. “‘Understanding Quality.’ Section B 4.1–1 of Introducing Bologna Objectives and Tools.” In EUA Bologna Handbook: Making Bologna Work, edited by L. Purser. Brussels: European University Association and Berlin, Raabe.

- Harvey, L. 2010. Twenty years of trying to make sense of quality assurance: the misalignment of quality assurance with institutional frameworks and quality culture. EURASHE events. 2010 5th EQAF. https://www.eurashe.eu/library/quality-he/WGSII.7_Papers_Harvey.pdf.

- Harvey, L., and D. Green. 1993. “Defining Quality.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 18 (1): 9–34. doi:10.1080/0260293930180102.

- Harvey, L., and B. Stensaker. 2008. “Quality Culture: Understanding, Boundaries and Linkages.” European Journal of Education 43 (4): 427–442. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/25481873.pdf?refreqid = excelsior%3A57e2e5fc75d747d656dbcd6cbe6a2505. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3435.2008.00367.x

- Kis, V. 2005. Quality assurance in tertiary education: current practices in OECD countries and a literature review on potential effects. Education and Training Policy Division, Directorate for Education, OECD. https://www.oecd.org/education/skills-beyond-school/38006910.pdf.

- Loukkola, T., and T. Zhang. 2010. Examining Quality Culture: Part 1 – Quality Assurance Processes in Higher Education Institutions. EUA Publications. Brussels: European University Association.

- Mayring, P. 2014. Qualitative content analysis theoretical foundation, basic procedures and software solution. https://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/bitstream/handle/document/39517/ssoar-2014-mayring-Qualitative_content_analysis_theoretical_foundation.pdf.

- Njiro, E. 2016. “Understanding Quality Culture in Assuring Learning at Higher Education Institutions.” Journal of Educational Policy and Entrepreneurial Research 3 (2): 79–92. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301227463_Understanding_Quality_Culture_in_Assuring_Learning_at_Higher_Education_Institutions.

- Norwegian Agency for Quality (NOKUT). 2018. Tilsyn med det systematiske kvalitetsarbeidet. [Audit of the systematic quality work]. Oslo: Nasjonalt organ for kvalitet i utdanningen. https://www.nokut.no/utdanningskvalitet/tilsyn-med-det-systematiske-kvalitetsarbeidet/.

- Persson, A. 1997. “‘Den Mångdimensionella Utbildningskvaliteten - Universitetet som Kloster, Marknad och Självorganisation.’ [The Multidimensional Quality of Education – the University as a Monastery, Market, and Self-Organization].” In Kvalitet och Kritiskt Tänkande [Quality and Critical Thinking]. Vol. 1997(6), edited by A. Persson, 45–67. Lund: Lund University.

- Quality Board for Icelandic Higher Education. 2017. Quality handbook for Icelandic higher education (2nd Edition, 2017). Reykjavik: Quality Board for Icelandic Higher Education. https://en.rannis.is/media/gaedarad/Final-for-publication-14-3-2017.pdf.

- Schindler, L., S. Puls-Elvidge, H. Welzant, and L. Crawford. 2015. “Definitions of Quality in Higher Education: A Synthesis of the Literature.” Higher Learning Research Communications 5 (3): 3–13. https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/hlrc/vol5/iss3/2/. doi: 10.18870/hlrc.v5i3.244

- Standards and guidelines for quality assurance in the European Higher Education Area, ESG. 2015. Brussels, Belgium. https://www.enqa.eu/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/ESG_2015.pdf.

- Sursock, A. 2011. Examining Quality Culture Part II: Processes and Tools – Participation, Ownership and Bureaucracy. EUA Publications. Brussels: European University Association. https://eua.eu/downloads/publications/examining%20quality%20culture%20part%20ii%20processes%20and%20tools%20-%20participation%20ownership%20and.pdf.

- Universitetskanslersämbetet. 2020. Vägledning för granskning av lärosätenas kvalitetssäkringsarbete. [Guidance for reviewing the higher education institutions’ quality assurance work]. Stockholm: Universitetskanslersämbetet. https://www.uka.se/publikationer–beslut/publikationer–beslut/vagledningar/vagledningar/2018-02-19-vagledning-for-granskningar-av-larosatenas-kvalitetssakringsarbete.html.

- Universitetskanslersämbetet. 2021. Vägledning för granskning av lärosätenas kvalitetssäkringsarbete avseende forskning. [Guidance for reviewing the higher education institutions’ quality assurance work concerning research]. Stockholm: Universitetskanslersämbetet. https://www.uka.se/publikationer–beslut/publikationer–beslut/vagledningar/vagledningar/2019-06-19-vagledning-for-granskning-av-larosatenas-kvalitetssakringsarbete-avseende-forskning.html.

- Vettori, O. 2012. Examining Quality Culture Part III: From Self-Reflection to Enhancement. EUA Publications. Brussels: European University Association. https://eua.eu/downloads/publications/examining%20quality%20culture%20part%20iii%20from%20self-reflection%20to%20enhancement.pdf.

- Vettori, O., and C. Rammel. 2014. “Linking Quality Assurance and ESD: Towards a Participative Quality Culture of Sustainable Development in Higher Education.” In Sustainable Development and Quality Assurance in Higher Education, edited by Z. Fadeeva, 49–65. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1057%2F9781137459145_3.pdf

- Wächter, B., M. Kelo, Q. Lam, P. Effertz, C. Jost, C., and S. Kottowski. 2015. University Quality Indicators: A Critical Assessment. Brussels: European parliament. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2015/563377/IPOL_STU%282015%29563377_EN.pdf.