ABSTRACT

This study examines how cost-benefit attitudes have a mediating role between residents' attitudes toward and support for tourism development. The theory of reasoned action (TRA) and social exchange theory (SET) are underpinning theories to support the hypotheses. The research was conducted in Şırnak province (Turkey), where tourism has not yet developed. A total number of 332 questionnaires were completed. The data were analysed using structural equation modelling. Results showed that residents' negative and positive attitudes toward tourism have direct effects on cost-benefit attitudes and indirect effects on support for tourism. It has also been determined that cost-benefit attitudes have a mediation role between residents' attitudes toward and support for tourism. The research contributes to the literature by adding social-psychological expressions to the residents' attitude concept toward tourism development. The research is also unique, because it was conducted in a place where tourism has not yet developed.

Introduction

The tourism sector is one of the most important drivers of social and economic development for underdeveloped and developing countries (Tosun & Timothy, Citation2001). Worldwide, 1.4 billion people travelled in 2018, with 1.7 trillion dollars in exports (UNWTO, Citation2019). Additionally, over 360 million people in 2019 were employed in the tourism sector (WTTC, Citation2020). With the consistent increase in travel around the world, not only economic impacts are experienced by communities and wider nations, but there are also social, cultural, environmental impacts (Andriotis & Vaughan, Citation2003; Çıkrık et al., Citation2019; Rivera et al., Citation2016). There are even political (Çelik & Uygur, Citation2017) and social–psychological impacts (Milman et al., Citation1990). Tourism has become an important phenomenon for both tourists and residents as they interact.

When tourism planning is to be made, stakeholders must participate in decision-making. Particular attention should be given to support from residents for tourism projects impacting their communities. An important segment of tourism-related literature reveals the social impacts of tourism are such that the participation of stakeholders and community-based planning should occur in the initial stages of the tourism development process. The literature even emphasizes that resident's participation is a necessary condition of success. This is because when residents participate in the tourism planning process, they tend to feel responsible for outcomes and accept the social effects of tourism. At the same time, understanding residents’ perspectives minimizes the potential negative effects of tourism development and maximizes their benefits. Participation can also facilitate community development and tourism support policies (Prayag et al., Citation2013; Stylidis et al., Citation2014). However, poor tourism planning can lead to negative consequences, weaken the entire industry, and negatively affect communities in the final destination (Jaafar et al., Citation2017; Jackson, Citation2008).

Many tourism and leisure studies measure the attitudes of residents towards tourism, but there are some deficiencies in these studies. First, residents perceptions either assessed with the triple bottom line approach (environmental, economic and socio-cultural effects) (Liu & Var, Citation1986; Lundberg, Citation2017; Rivera et al., Citation2016; Stylidis et al., Citation2014; Yoon et al., Citation2001; Akis et al., Citation1996) or positive and negative perceptions towards tourism (Dillette et al., Citation2017; Ko & Stewart, Citation2002; McGehee & Andereck, Citation2004; Nunkoo & Gursoy, Citation2012; Rasoolimanesh et al., Citation2018; Ribeiro et al., Citation2017) are measured (Ngowi & Jani, Citation2018). In some (Asyraf Afthanorhan et al., Citation2017; Martín et al., Citation2018; Prayag et al., Citation2013), the mix of the two approaches was used. However, it is an unfortunate deficiency that the social–psychological effects of tourism from the perspective of the residents are not addressed. However, in the literature (Anastasopoulos, Citation1992; Çelik, Citation2019a, Citation2019b;Günlü et al., Citation2015; Milman et al., Citation1990; Pearce & Wu, Citation2016; Reisinger & Turner, Citation2003; Uriely et al., Citation2009), it is widely known that tourism provides peace among communities by reducing prejudices. Of course, some studies show that they change attitudes more negatively (Anastasopoulos, Citation1992; Sirakaya-Turk et al., Citation2014). In other words, tourism affects intergroup/inter-communal attitudes (Tomljenovic, Citation2010). Therefore, in this study, social–psychological attitudes were added to the attitude scale towards tourism.

A second important shortcoming in past studies (Carneiro et al., Citation2018; Eki̇ci̇ & Çizel, Citation2014; Eusébio et al., Citation2018; Jani, Citation2018; Joo et al., Citation2018; Ko & Stewart, Citation2002; Liu & Var, Citation1986; Long, Citation2011; Martín et al., Citation2018; Ngowi & Jani, Citation2018) in that the research was done in places where tourism has developed, and few studies have been in places where tourism is yet to be developed (Eusébio et al., Citation2018; Hernandez et al., Citation1996). This shows that research is lacking at some points. There is an important deficiency that tourism, which is seen as a tool for sustainable development, has been less studied in less developed countries (Eusébio et al., Citation2018). This lack of research may be because these regions face economic and social constraints that hinder development and therefore are not included in tourism planning (Eusébio et al., Citation2018). This situation makes it necessary to study the subject in these regions, not just in more developed places. In addition, a better and more comprehensive approach would be to examine the residents view of tourism before developing tourism and to develop a planning policy according to the result. From this point of view, this research was carried out in a place of low socio-economic level and where tourism has not developed.

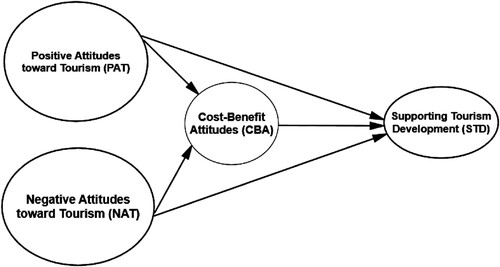

The main purpose of this study is to show the mediating role of cost–benefit attitudes (CBA) in the effect of residents’ attitudes towards tourism (RATT) on supporting tourism development (STD) attitudes. The study also is aimed to reveal the role of temporal change by doing the research again in the future. The basis of this research is the theory of reasoned action (TRA) of Fishbein and Ajzen (Citation1975), and social exchange theory (SET) of Ap (Citation1992). Using quantitative research methods, the data were collected through surveys.

The study has some important contributions. First, expressions including social–psychological effects were added to the expressions about the perception of tourism obtained from the literature, and it was provided to be handled more broadly. Second, the research was conducted in Şırnak/Turkey, where tourism has not yet developed. The questions started by saying “If tourism develops” to contextualize the query to probe respondents imagining a potential future (e.g. “if tourism develops, it provides more employment for my city”). Hernandez et al. (Citation1996) stated that studies focusing on the pre-tourism stage can make a special contribution to research in this field. Third, the study provides a longitudinal research opportunity. Fourth, as a practical contribution, study results can be used as a guide for decision-makers and industry representatives. Researchers state that although the issue of the effects of tourism has been studied extensively, it will be beneficial to study in other regions, in different environments and times to better understand the support for tourism development (Long, Citation2011, p. 76).

Literature review

Theoretical framework

The perspective of residents on tourism began to be studied starting in the 1980s (Rasoolimanesh & Jaafar, Citation2016). While the studies in the 1970s aimed to capture and define snapshots of economic benefits of tourism, today, their focus is on causal relationships. They tried to be explained with theories from different fields, including models like TRA (Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation1975), theory of planned behaviour (Ajzen, Citation1985), social representation theory (Moscovici, Citation1984), SET (Ap, Citation1992; Homans, Citation1950), tourist area life cycle model (Butler, Citation1980), and irritation index model (Doxey, Citation1975). This study uses two important theories: Ajzen and Fishben's TRA, and Ap's SET.

One of the models explaining the attitude–behaviour relationship as a means to explain attitude and supporting behaviour towards tourism is the TRA model of Fishbein and Ajzen (Citation1975). The theory explains the relationship between consumers’ beliefs, attitudes, intentions, and behaviours (Yuzhanin & Fisher, Citation2016). This theory was later expanded by the addition of perceived behavioural control variable (Ajzen, Citation1985) and took its place in the literature as the “theory of planned behaviour (TPB)”. TPB assumes that three structures will guide behaviour: attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control (Ajzen, Citation1985). When we apply the TRA to tourism, we should see that if the residents have a positive attitude towards tourism, then they can display behaviour to support tourism activities (Nunkoo & Ramkissoon, Citation2010). In tourism studies, TRA has been successfully used to enable residents to better understand their attitudes to support tourism development (Ribeiro et al., Citation2017). The theory, which focuses on attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control, not only allows researchers to understand the behavioural determinants of tourism but also allows academics to determine the strength of these variables in influencing the host community's behaviour towards tourism (Nunkoo & Ramkissoon, Citation2010).

The other most widely accepted theory explaining residents’ attitudes on tourism is social exchange theory (Stylidis et al., Citation2014) because it allows different views based on experiential and psychological results (Prayag et al., Citation2013, p. 630). If perceived positive effects (benefits) outweigh potential negative consequences (costs), residents of the region will more likely support tourism development (Eki̇ci̇ & Çizel, Citation2014, p. 74).

Residents’ attitudes toward tourism

Attitude expresses positive, negative, or neutral tendencies towards something or a person (Eagly & Chaiken, Citation1993). Positive, negative, or neutral perceptions of residents towards tourism reveal residents’ attitudes towards tourism. Because residents collaboration is essential to the success and sustainability of any tourism development project, understanding the views of residents and acquiring needed support is of great importance for local government, policymakers, and businesses (Stylidis et al., Citation2014). Also, since the attitudes of residents impact the satisfaction and loyalty of visitors (Ribeiro et al., Citation2017), understanding the perspectives of residents on tourism development (Gabriel Brida et al., Citation2011) plays a vital role in the success of a destination (Long, Citation2011).

Residents were included in diverse ways in research involving attitudes towards tourism. Some are “attitudes towards the effects of tourism” (Andereck et al., Citation2005; Ap, Citation1992; Carneiro et al., Citation2018; Gabriel Brida et al., Citation2011), others “attitudes towards tourism” (Andereck & Vogt, Citation2000; Gursoy & Rutherford, Citation2004; Vargas-Sánchez et al., Citation2011) and “attitudes towards tourism development” (Akis et al., Citation1996; Andriotis & Vaughan, Citation2003; Rasoolimanesh & Jaafar, Citation2016; Stylidis, Citation2018). Since the location of this study has not been opened to tourism yet, it is considered as the attitude towards tourism.

Studies measuring tourism perception dwell on negative and positive attitudes towards environmental, socio-cultural, and economic impact dimensions. However, regardless of the dimensions it is seen in the literature that the social–psychological effects of tourism are not used. However, the positive and negative effects of tourism, especially on conflict groups (state, society, etc.), have been revealed in many studies (Ajanovic et al., Citation2016; Amir, Citation1969; Pearce, Citation1982; Uriely et al., Citation2009).

Prayag et al. (Citation2013) measured residents’ attitudes towards the London Olympic Games in their study. According to the research results, perceived positive–negative economic and socio-cultural affects overall attitude. Jaafar et al. (Citation2017) found that positive impacts had a positive effect on community participation (such as tourism support). Also, Rasoolimanesh et al. (Citation2015) found that positive perceptions affect support of tourism development positively and negative perceptions affect it negatively. In another study, positive attitudes of the people towards tourism have a positive effect on the overall satisfaction (Ko & Stewart, Citation2002). Similarly, Chen and Chen (Citation2010) found that tourism support was positively influenced by the positive impacts. Also Eusébio et al. (Citation2018) found that perception of positive impacts positively affects the attitudes of the people towards tourism development. The negative impact perception of residents negatively affected the attitudes towards tourism development. Jurowski et al. (Citation1997) found that social, environmental, and economic impacts affect support. As a result of the research of Martín et al. (Citation2018), perception of positive economic, socio-cultural impacts affect positively and perception of negative socio-cultural impact affect negatively on attitude towards tourism. In another study, Shen et al. (Citation2010) found in their study that residents’ positive attitudes to tourism, place attachment, and image affect pro-tourism behavioural intention. Also SET and TRA explain that the perception of cost–benefit of the residents may affect attitudes towards tourism. The current study reported here used the cost–benefit concept instead of total impact or overall impact. As a result, the following hypotheses were developed.

H1: Positive attitudes towards tourism have a positive effect on cost–benefit attitudes.

H2: Positive attitudes towards tourism have a positive effect on supporting tourism development.

H3: Negative attitudes towards tourism have a negative effect on cost–benefit attitudes.

H4: Negative attitudes towards tourism have a negative effect on supporting tourism development.

Cost–benefit attitudes

Many studies (Brunt & Courtney, Citation1999; Jurowski et al., Citation1997; Liu & Var, Citation1986; Perdue et al., Citation1990; Pizam, Citation1978) revealed the positive and negative impacts of tourism. Therefore, people clearly choose between benefits and costs. In the SET, if residents perceive that the positive effects of tourism in terms of economic, sociocultural, and environmental benefits are greater than costs or negative effects, they will have a positive attitude towards tourism development in their communities (Martín et al., Citation2018, p. 232).

The cost–benefit variable is sometimes considered as the total effect (Yoon et al., Citation2001) and as the overall attitude (Prayag et al., Citation2013). Prayag et al. (Citation2013) stated that in models with overall attitude and supporting tourism development variables, it is problemic to use the concepts of overall attitude and overall satisfaction and not to make more subtle distinctions. In order not to be confused with general attitude and general satisfaction, as well as considering the dimension's content, it is more accurate to call this dimension cost–benefit.

Nunkoo and Ramkissoon (Citation2011) establish that cost–benefit perceptions directly affect support of tourism. Also, Yoon et al. (Citation2001) argued that overall total impact effects support for tourism. Some studies (e.g. Andereck & Vogt, Citation2000; Yoon et al., Citation2001) show that overall attitude mediates the relationship between perceived impacts and support of tourism development. As a result, the following hypotheses were developed.

H5: Cost–benefit attitudes have a positive impact on supporting tourism development.

H6: There is an indirect relationship between positive attitudes and supporting tourism development mediated by cost–benefit attitudes.

H7: There is an indirect relationship between negative attitudes and supporting tourism development mediated by cost–benefit attitudes.

Supporting tourism development attitudes

The support of the residents is necessary for the development, successful management, and maintenance of tourism. If the residents have a positive perception of tourism, they will support tourism development and therefore will be willing to interact with visitors such as in selling goods and services (Yoon et al., Citation2001). However, if they think that the cost of tourism is too much, anger, indifference, and insecurity will appear (Doxey, Citation1975). Also, TRA shows that the attitude towards tourism will affect STD. Most of the research that measures the perception of the residents assumes that there is a linear relationship between the perceptions of the residents and the supporting development of tourism (Rasoolimanesh et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, general satisfaction (Nunkoo & Ramkissoon, Citation2011), total impact (Prayag et al., Citation2013; Yoon et al., Citation2001), place image (Shen et al., Citation2010), economic, environmental, socio-cultural (Jaafar et al., Citation2017) and demographic variables (Long, Citation2011) reveal that perception affects the behaviour of supporting tourism development ().

Method

The main purpose of this research is to predict the mediating role of the CBA in the impact of perceived negative and positive attitudes of residents towards tourism on STD perception. Also, in Şırnak, which has not yet developed its tourism sector, the attitude levels of the people towards tourism are a sub-objective as is to carry out a longitudinal study by doing the work after the development of tourism occurs, and to contribute to the literature on the social–psychological perception of attitudes towards tourism. For these purposes, the quantitative research method was used. Online and face-to-face survey techniques were used to obtain the data.

Research location

The research was conducted in Şırnak province in Turkey. Şırnak is undeveloped in terms of socio-economics development. It is close to the Iraqi border and has a Habur border gate. Şırnak is a place where Arab, Kurdish, Turkish, Syriac, Armenian, and Ezidi people live from past to present. So Şırnak has a rich culture and is characterized by tolerance. Many people believe that the ship Noah built in Biblical times sat on the Cudi Mountain in Şırnak after the Flood of Noah. This fact indicates a potential to attract the world to Şırnak in terms of tourism. Also, it contains natural beauty (waterfalls, valleys, and canyons) and historical and cultural riches (red madrasah, hospitality, Syriac and Ezidi cultures, Chaldean monasteries). Such riches contain especially important elements in terms of tourism marketing. However, these riches cannot be currently used. Therefore, it is predicted that the underdeveloped tourism sector can be used as a development tool.

Research sample

The population of Şırnak in 2019 is 529,615, which includes the surrounding villages (Turkish Statistical Institute [TÜİK], Citation2020). Convenience, haphazard sampling method was used to collect data from a total of 332 people. Respondents were individuals over 18 years of age and surveys were conducted from February 15 to May 30, 2019 using online and face-to-face questionnaires. This number is enough for evaluating the statistical model used for analysis (Hair et al., Citation2019; Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2006). The average age of the participants was 30, and the average of income was 7600 Turkish Lira, while 79% of respondents were males and most had undergraduate and postgraduate education (56%), whereas 54% were married.

Instruments

Positive/negative attitudes towards tourism (PAT, NAT): For attitudes towards tourism; environmental, economic, social, cultural, and social–psychological variables are handled with negative and positive aspects. Several studies (Akis et al., Citation1996; Liu & Var, Citation1986; Yoon et al., Citation2001) have been used to measure the positive and negative attitudes of people towards tourism. In addition to expressions, five questions were added to measure attitudes towards social–psychological effects (e.g., if tourism develops, prejudices between people decrease). The questions were created by making use of tourism-social psychological studies (Amir & Ben-Ari, Citation1985; Anastasopoulos, Citation1992; Çelik, Citation2019a; Günlü et al., Citation2015; Litvin, Citation2003; Milman et al., Citation1990; Pearce, Citation1982; Sirakaya-Turk et al., Citation2014). A total of 27 questions were asked for residents’ attitudes towards tourism.

Cost–benefit attitudes (CBA): A total of three questions were asked to determine the cost–benefit attitudes of the residents towards tourism. While creating these questions, Long (Citation2011) and Yoon et al.'s (2001) studies were used.

Supporting tourism development (STD): Five questions were taken from the study of Eusébio et al. (Citation2018) to determine whether residents will support tourism development.

The tourism sector has not yet developed in the research area. That is why the questions are started “if tourism develops” in the questionnaire. For example, “If tourism develops, tourists negatively affect our lifestyle.” A five-point Likert scale was used as the measurement scale for these all items with assigned values ranging from 1 “strongly disagree to 5 strongly agree”.

Data analysis process

After taking the opinions of the experts, the questionnaire prepared was completed by 35 people for superficial validity. There were no questions that were not understood. Subsequently, a pilot study was conducted with 116 people, and Cronbach's Alpha values were determined to be attitudes towards tourism (positive and negative) 0.93, cost–benefit 0.75, and STD 0.94. Attitudes towards tourism emerged as two dimensions (negative and positive) in exploratory factor analysis.

First, the data were reviewed using the SPSS program. Incorrectly entered data were corrected and reverse codes were made. Missing data were filled in utilizing the average value of observations. Then, exploratory factor analysis was performed with the varimax rotation technique. It was observed that the attitude questions towards tourism were gathered under two (positive and negative) dimensions. It was seen that the expressions related to social psychological attitudes were distributed into these two dimensions. Three of the attitude statements towards tourism (eco1, eco5) (factor load is <.40) were omitted. The positive dimension consisted of 14 questions and the negative dimension consisted of ten questions. Cronbach's alpha coefficient of attitudes towards tourism was determined to be 89%. The variance explained by these factors was found to be as high as 73%. Cost–benefit attitudes emerged with one dimension and one statement (CBA3) was omitted (factor load <.40). CBA's Cronbach's alpha was determined as 0.72 and total variance explained as 78%. For the STD variable, it was seen that the total explained variance in which the expressions came out in one dimension was 70% and the Cronbach's alpha value was 0.93.

After this stage, confirmatory factor analysis, measurement model, and mediation analysis were performed. Skewness–kurtosis values were examined for normality values. It was observed that the skewness (−1.536/−0.082) and kurtosis (1.121/–.080) values were in the range of ±2 (Kunnan, Citation1998, p. 313) and showed acceptable multivariate normality for all constructs in the model. In SEM, the maximum probability estimation method (Jöreskog & Sörbom, Citation1993) and the two-stage testing process of Anderson and Gerbing (Citation1988) were applied. Initially, the measurement model and then the structural model were examined. The determined model was introduced by using SEM with the AMOS program.

Findings and results

Assessment of measurement model

Before moving on to structural model assessment, the measurement model in which all factors are included was assessed. To assess the model, confirmatory factor analysis was performed. The scale consisted of 31 items and 4 dimensions (). Several modifications were made to the model. While improving, variables that reduce compliance were determined and new covariance was created for those with higher covariance among the values.

Table 1. Assessment results of the measurement model.

Afterward, it was observed that the values accepted for the fit indices were provided in the fit index calculations. When the fit indices of the measurement model are examined within the framework of the recommendations of various researchers (Adams et al., Citation1992; Gefen et al., Citation2000; Jöreskog & Sörbom, Citation1993) (χ2: 947.122, df: 422, p: 0.000 χ2/df: 2.244 -RMSEA: 0.06- AGFI: .80-GFI: 0.83-NFI: 0.90-CFI: 0.94); the measurement model is determined to be good and acceptable.

To determine the reliability of the measurement model, the Average Variance Extracted (AVE), Composite Reliability (CR), and loading of each item were checked. The latent variables of the measurement model are expected to have a CR higher than 0.70 (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981, p. 40) and AVE of greater than 0.50 to establish reliability and convergent validity (Hair et al., Citation2019, p. 124). As seen in , CR values are above the threshold value of 0.70 and AVE values are above the threshold value of 0.50, and all loadings are 0.5, thereby establishing the reliability and validity of all constructs.

Assessment of the structural model

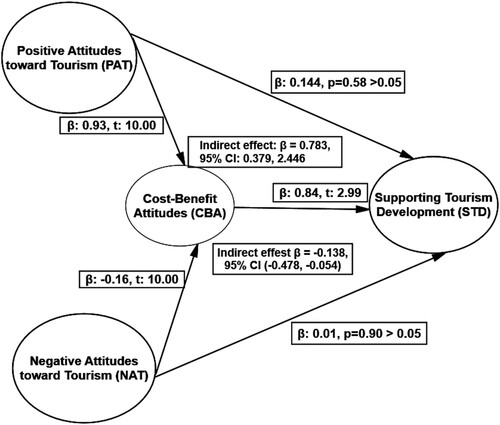

For testing the model, the modern approach of Hayes (Citation2013) was taken into consideration. Then, the model was analysed using the bootstrap method. In the model in which the mediating role of the CBA variable was investigated in the effect of positive and negative attitudes towards tourism on STD; it was determined that PAT has a high-level positive effect on CBA (β: 0.93, t: 10.00) (H1 accepted). Also, the effect of NAT on CBA turned out to be significantly negative at a low level (β: −0.16, t: 10.00) (H3 accepted). The other result showed that the effect of CBA on the STD variable was found to be high and positive (β: 0.84, t: 2.99) (H5 accepted). Also, the average adjusted R2 of CBA 0.87 and STD 0.95 ().

Table 2. Results of hypothesis testing.

With the addition of CBA to the model as a mediation, the pre-existing effect of PAT and NAT dimensions on the STD variable (respectively, β = 0.89, p < 0.05, p < 0.05, β: −0.18, t: 3.10) disappeared. In the mediation model, it was found that the direct effects of PAT and NAT dimensions on the STD variable were not significant (p = 0.58 > 0.05–p = 0.90 > 0.05, respectively) (H2, H4 rejected). However, it was determined that PAT (β = 0.783, 95% CI: 0.379, 2.446) and NAT (β = −0.138, 95% CI −0.478, −0.054) had an indirect effect on STD (H6, H7 accepted).

In the bootstrap method used, the bootstrap lower (BootLLCI) and upper (BootULCI) values in the 95% confidence interval do not contain “0” (Hayes, Citation2018, p. 95) and the model fit indexes are acceptable and good, so CBA has a full mediating role in the effect of PAT (lower–upper –0.379–2.446) and NAT (lower–upper-0.478- −0.054) variables on STD (χ2/df: 2.3111, RMSEA: 0.063, GFI: 0.831, AGFI: 0.801, IFI: 0.938, CFI: 0.938) ().

Discussion

In this study, which is carried out in a place where tourism has not developed yet, the effect of residents’ attitudes towards tourism on supporting tourism development and the mediation role of the benefit–cost variable in this effect were investigated. As a result of the research, people's perspective on tourism was examined with a dual structure in the form of negative and positive attitudes.

When we evaluate the results, it is seen that the people's perspective on tourism is generally positive ( mean values). However, we see that the viewpoint of public tourism is close to both PAT (Mean = 3.76) and NAT (Mean = 3.59). This shows that the public perceives tourism in both ways. This is a key point. Because the attitudes towards STD (Mean = 3.87) and CBA (Mean = 3.74), which are among other variables, are positive, when the tourism develops in the future, the people will act knowing the positive and negative aspects of tourism. It is important for the support of the public for the development of the tourism sector in Şırnak.

Other important results of the research include the effect of positive–negative tourism attitudes on CBA has emerged, as in some studies (Prayag et al., Citation2013; Yoon et al., Citation2001). Unlike these studies, this result has emerged in a place where the tourism industry has never existed. The residents have attitudes about tourism before they benefit from the tourism sector, and CBA and STD can be affected within the framework of these attitudes. Considering the SET theory, the reasons for this may vary. First, public awareness of tourism is a principal factor. Besides, it is a point that may be effective in supporting tourism in variables such as the poor socioeconomic status of Şırnak province and its high unemployment rate. Furthermore, Şırnak is an open and not closed society because it is located on the Iraqi border. It is thought to be effective in this case.

There was no surprise in the results showing the effect of PAT on CBA was positive and NAT's effect on CBA was negative. Indeed, some studies yielded similar results (Dyer et al., Citation2007; Eki̇ci̇ & Çizel, Citation2014; Nunkoo & Gursoy, Citation2012; Prayag et al., Citation2013; Yoon et al., Citation2001). The emergence of a place where there is no tourism sector makes it different from other studies. It shows that the residents have attitudes towards tourism without benefiting from the tourism sector. In a place where there is no tourism sector yet, social representations theory (Moscovici, Citation1984) can be used to reveal sociologically what affects perceptions of tourism. It is important to explain representations that affect people's attitudes.

The study also showed that CBA has a high positive effect on STD. This shows that SET and TRA theories are supported in a place where tourism is yet to develop. Prayag et al. (Citation2013) used the overall attitude variable in their studies. Looking at the items of this variable, it is seen that it is like CBA. In their studies, it is seen that the overall attitude has a significant effect on the behaviour of supporting tourism. Also, Yoon et al.'s (2001) research supports this result. Ribeiro et al. (Citation2017) found a positive relationship between economic benefit and STD. Additionally, Su and Swanson (Citation2020) found that personal benefit from tourism has a positive effect on STD. In some studies (Keogh, Citation1990; Milman & Pizam, Citation1988; Sheldon & Var, Citation1984), the opposite situation was revealed. However, Gursoy and Rutherford (Citation2004) found that social cost, social benefit, and cultural cost dimensions do not affect STD, but economic and cultural benefit dimensions affect STD. We can see similar results in Jurowski et al. (Citation1997) and Tosun (Citation2002). Gursoy et al. (Citation2002) linked this situation to the economic situation of the place where they live. The socioeconomic situation of Şırnak province is bad and unemployment is high. We can say that it is effective in the relationship between CBA and STD.

Another result is that CBA has a mediation role and PAT and NAT have indirect effects on STD. Although the number of studies dealing with the mediating role of CBA is low, we can see similar results in existing studies. Prayag et al. (Citation2013) found that the overall attitude variable has a mediation role between the perceived tourism effects variable and the residents’ support of the games in the study, which measures the residents’ perception regarding the Olympic games.

One of the important results of this study is the addition of questions (see : items: sospsi1,2,3,4,5) to the expressions of tourism perception that will reveal the social–psychological effects of tourism. It has been seen in the literature that social psychological effects are not used. However, the social–psychological benefits of tourism may be more important than economic benefits for residents, especially where there is a high-security risk, where there is social discrimination, hostilities, and conflicts (these places are many).

Theoretical and practical implications

First, it is important that this research has been researched in an area where tourism has not yet developed and enables longitudinal research in the future. It has been observed that SET (Ap, Citation1992) and TRA (Ajzen, Citation1985) theories, which the subject is based on in the literature, can give similar results in regions where tourism does not develop. This means that even if the resident is not confronted with the tourism sector, it can perceive tourism in terms of cost–benefit. The reasons for this needs to be investigated. This situation provides us with the necessary materials to determine the perceptions of the places that will enter the tourism sector and manage the place. In this way, the perceptions of the people towards tourism can be determined and the negative perceptions can be changed, and at the same time, the awareness of the residents about tourism can be provided.

The second important theoretical contribution of this research is the inclusion of social–psychological items in the perception of tourism. In previous studies (Chen & Chen, Citation2010; Dyer et al., Citation2007; Eki̇ci̇ & Çizel, Citation2014; Jaafar et al., Citation2017; Nunkoo & Ramkissoon, Citation2010; Perdue et al., Citation1990; Rasoolimanesh et al., Citation2018, etc.), it was observed that there was no item, dimension or a variable containing the social psychological effects of tourism. However, tourism has a social–psychological effect and the studies that demonstrate this are many (Amir & Ben-Ari, Citation1985; Çelik, Citation2019c; Günlü et al., Citation2015; Jafari, Citation1989; Kim et al., Citation2007; Ming, Citation2018; Pearce, Citation1982; Pearce & Wu, Citation2016).

In future studies, researchers should determine perception by measuring the resident's perspective on tourism from time to time. Additionally, in terms of the tourism sector, the point of view of residents is important to make comparisons in the future and to reveal the life stages of tourism. Also, comparisons should be made between both developed and underdeveloped countries. Besides, the effects of tourism should be managed not only in the context of negative–positive, economic, environmental, socio-cultural but also in social psychological effects. There is a need for a scale for this.

This research sends messages to public institutions and organizations in the private sector in Şırnak. According to the results, the participants of the research know perceptually both the negative and positive effects of tourism. Although they know the negative effects of tourism, they support tourism by making cost–benefit analysis. In other words, the public accepts the tourism sector. If investments related to tourism are made, public support will be behind them. At least within the framework of the research sample, the research results show this. Tourism investments will be made in Şırnak, which is one of the most backward provinces of the country in socio-economic terms, where unemployment is high, and the people will participate in the economic cycle.

The natural and cultural riches of Şırnak are mostly found in the districts. Consequently, the difference between rural and urban socio-cultural development of Şırnak tourism can be reduced by tourism. When investments are made in the tourism sector in Şırnak, it is imperative to calculate the carrying capacity and to meet the infrastructure and superstructure needs to the extent necessary. Otherwise, even if tourism develops, it will develop uncontrollably. This situation causes the public to complain about tourists and tourism. In other words, the sustainability of tourism will be at risk. We can easily understand this from the dissatisfaction of many countries in the world (Spain, Italy, among others) from over-tourism. To prevent this, a commission that will bring together tourism stakeholders for Şırnak should be established and a tourism master plan should be created. Of course, at this point, it is important to ensure the participation of the public and other stakeholders in the decisions.

There are some limitations in this study; First, the study was attended by three districts of Şırnak. Although it is thought that there are no sociological differences among the four districts, it is important to collect data from the remaining four districts to more comprehensively get the ideas of Şırnak residents. Another important limitation is that it is quite difficult to survey Şırnak. People are afraid to fill in the questionnaire. Besides, the people over the middle age who will not fill the questionnaire (because they do not know how to read and write) are more, which led us to collect data from more educated people. For all these reasons, authors made the questionnaire face to face first and then continued it online. Observing this situation in the studies to be conducted hereinafter will benefit the studies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adams, D. A., Nelson, R. R., & Todd, P. A. (1992). Perceived usefulness, ease of use, and usage of information technology: A replication. MIS Quarterly, 16(2), 227–247. https://doi.org/10.2307/249577

- Afthanorhan, A., Awang, Z., & Fazella, S. (2017). Perception of tourism impact and support tourism development in Terengganu, Malaysia. Social Sciences, 6(3), 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci6030106

- Ajanovic, E., Çizel, B., & Çizel, R. (2016). Effectiveness of Erasmus programme in prejudice reduction: Contact theory perspective. Turisticko Poslovanje, 17(17), 47–60. https://doi.org/10.5937/TurPos1617047A

- Ajzen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In Action control (pp. 11–39). Springer.

- Akis, S., Peristianis, N., & Warner, J. (1996). Residents’ attitudes to tourism development: The case of Cyprus. Tourism Management, 17(7), 481–494. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(96)00066-0

- Amir, Y. (1969). Contact hypothesis in ethnic relations. Psychological Bulletin, 71(5), 319–342. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0027352

- Amir, Y., & Ben-Ari, R. (1985). International tourism, ethnic contact, and attitude change. Journal of Social Issues, 41(3), 105–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1985.tb01131.x

- Anastasopoulos, P. G. (1992). Tourism and attitude change: Greek tourists visiting Turkey. Annals of Tourism Research, 19(4), 629–642. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(92)90058-W

- Andereck, K. L., Valentine, K. M., Knopf, R. C., & Vogt, C. A. (2005). Residents’ perceptions of community tourism impacts. Annals of Tourism Research, 32(4), 1056–1076. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2005.03.001

- Andereck, K. L., & Vogt, C. A. (2000). The relationship between residents’ attitudes toward tourism and tourism development options. Journal of Travel Research, 39(1), 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728750003900104

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411.

- Andriotis, K., & Vaughan, R. D. (2003). Urban residents’ attitudes toward tourism development: The case of Crete. Journal of Travel Research, 42(2), 172–185. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287503257488

- Ap, J. (1992). Residents’ perceptions on tourism impacts. Annals of Tourism Research, 19(4), 665–690. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(92)90060-3

- Brunt, P., & Courtney, P. (1999). Host perceptions of sociocultural impacts. Annals of Tourism Research, 26(3), 493–515. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(99)00003-1

- Butler, R. W. (1980). The concept of a tourist area cycle of evolution: Implications for management of resources. Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe Canadien, 24(1), 5–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0064.1980.tb00970.x

- Carneiro, M. J., Eusébio, C., & Caldeira, A. (2018). The influence of social Contact in residents’ perceptions of the tourism impact on their quality of life: A structural equation model. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 19(1), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/1528008X.2017.1314798

- Çelik, S. (2019a). Does tourism reduce social distance? A study on domestic tourists in Turkey. Anatolia, 30(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2018.1517267

- Çelik, S. (2019b). Does tourism change tourist attitudes (prejudice and stereotype) towards local people? Journal of Tourism and Services, 10(18), 35–46. https://doi.org/10.29036/jots.v10i18.89

- Çelik, S. (2019c). Evaluation of the tourist–local people interaction within the context of Allport’s intergroup contact theory. In The Routledge Handbook of tourism impacts theoretical and applied perspectives (pp. 242–251). Routledge.

- Çelik, S., & Uygur, M. N. (2017). An evaluation of the impacts of international political crises on Turkish tourism. In R. Efe, R. Penkova, J. A. Wendt, K. T. Saparov, & J. G. Berdenov (Eds.), Developments in social Sciences (pp. 623–631). St. Kliment Ohridski University Press.

- Chen, C.-F., & Chen, P.-C. (2010). Resident attitudes toward heritage tourism development. Tourism Geographies, 12(4), 525–545. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2010.516398

- Çıkrık, R., Yılmaz, İ, & Toprak, L. S. (2019). Bibliometric profile of postgraduate theses related to impacts of tourism from the perspective of local people. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Issues, 1(1), 17–29.

- Dillette, A. K., Douglas, A. C., Martin, D. S., & O’Neill, M. (2017). Resident perceptions on cross-cultural understanding as an outcome of volunteer tourism programs: The Bahamian Family Island perspective. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(9), 1222–1239. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2016.1257631

- Doxey, G. V. (1975). A causation theory of visitor-resident irritants: Methodology and research inferences. In Proceedings of the Travel Research Association 6th Annual Conference (pp. 195–198). Travel Research Association.

- Dyer, P., Gursoy, D., Sharma, B., & Carter, J. (2007). Structural modeling of resident perceptions of tourism and associated development on the Sunshine Coast, Australia. Tourism Management, 28(2), 409–422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2006.04.002

- Eagly, A. H., & Chaiken, S. (1993). The psychology of attitudes. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers.

- Eki̇ci̇, R., & Çizel, B. (2014). Yerel Halkın Turizm Gelişimi Desteğine İlişkin Tutumlarının Destinasyonların Gelişme düzeylerine göre Farklılıkları. Seyahat ve Otel İşletmeciliği Dergisi, 11(3), 73–87.

- Eusébio, C., Vieira, A. L., & Lima, S. (2018). Place attachment, host–tourist interactions, and residents’ attitudes towards tourism development: The case of Boa Vista Island in Cape Verde. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(6), 890–909. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1425695

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Addison-Wesley.

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Gabriel Brida, J., Osti, L., & Faccioli, M. (2011). Residents’ perception and attitudes towards tourism impacts: A case study of the small rural community of Folgaria (Trentino – Italy). Benchmarking: An International Journal, 18(3), 359–385. https://doi.org/10.1108/14635771111137769

- Gefen, D., Straub, D. W., & Boudreau, M.-C. (2000). And regression: Guidelines for research practice. Communication for the Association of Information System, 4, 7. https://doi.org/10.17705/1CAIS.00407

- Günlü, E., Özgen, HKŞ, Dilek, S. E., Kaygalak, S., Türksoy, S. S., & Lale, C. (2015). Turkish visitors in Armenia: Any changes in attitudes and perceptions? Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Management, 3(1), 29–43. https://doi.org/10.15640/jthm.v3n1a3

- Gursoy, D., Jurowski, C., & Uysal, M. (2002). Resident attitudes: A structural modeling approach. Annals of Tourism Research, 29(1), 79–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(01)00028-7

- Gursoy, D., & Rutherford, D. G. (2004). Host attitudes toward tourism: An improved structural model. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(3), 495–516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2003.08.008

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. The Guilford Press.

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (second edition). Guilford Press.

- Hernandez, S. A., Cohen, J., & Garcia, H. L. (1996). Residents’ attitudes towards an instant resort enclave. Annals of Tourism Research, 23(4), 755–779. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(95)00114-X

- Homans, G. C. (1950). The human group. Harcourt, Brace.

- Jaafar, M., Rasoolimanesh, S. M., & Ismail, S. (2017). Perceived sociocultural impacts of tourism and community participation: A case study of Langkawi Island. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 17(2), 123–134. https://doi.org/10.1177/1467358415610373

- Jackson, L. A. (2008). Residents’ perceptions of the impacts of special event tourism. Journal of Place Management and Development, 1(3), 240–255. https://doi.org/10.1108/17538330810911244

- Jafari, J. (1989). Tourism and peace. Annals of Tourism Research, 16(3), 439–443. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(89)90059-5

- Jani, D. (2018). Residents’ perception of tourism impacts in Kilimanjaro: An integration of the social exchange theory. Tourism, 66(2), 148–160.

- Joo, D., Tasci, A. D. A., Woosnam, K. M., Maruyama, N. U., Hollas, C. R., & Aleshinloye, K. D. (2018). Residents’ attitude towards domestic tourists explained by contact, emotional solidarity and social distance. Tourism Management, 64, 245–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.08.012

- Jöreskog, K. G., & Sörbom, D. (1993). LISREL 8: Structural equation modeling with the SIMPLIS command language. Scientific Software International.

- Jurowski, C., Uysal, M., & Williams, D. R. (1997). A theoretical analysis of host community resident reactions to tourism. Journal of Travel Research, 36(2), 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728759703600202

- Keogh, B. (1990). Resident recreationists’ perceptions and attitudes with respect to tourism development. Journal of Applied Recreation Research, 15(2), 71–83.

- Kim, S. S., Prideaux, B., & Prideaux, J. (2007). Using tourism to promote peace on the Korean Peninsula. Annals of Tourism Research, 34(2), 291–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2006.09.002

- Ko, D.-W., & Stewart, W. P. (2002). A structural equation model of residents’ attitudes for tourism development. Tourism Management, 23(5), 521–530. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(02)00006-7

- Kunnan, A. J. (1998). An introduction to structural equation modelling for language assessment research. 295–332.

- Litvin, S. W. (2003). Tourism and understanding. Annals of Tourism Research, 30(1), 77–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(02)00048-8

- Liu, J. C., & Var, T. (1986). Resident attitudes toward tourism impacts in Hawaii. Annals of Tourism Research, 13(2), 193–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(86)90037-X

- Long, P. H. (2011). Perceptions of tourism impact and tourism development among residents of Cuc Phuong National Park, Ninh Binh, Vietnam. Journal of Ritsumeikan Social Sciences and Humanities, 3, 75–92.

- Lundberg, E. (2017). The importance of tourism impacts for different local resident groups: A case study of a Swedish seaside destination. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 6(1), 46–55.

- Martín, H. S., de los Salmones Sánchez, M. M. G., & Herrero, Á. (2018). Residents' attitudes and behavioural support for tourism in host communities. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 35(2), 231–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2017.1357518

- McGehee, N. G., & Andereck, K. L. (2004). Factors predicting rural residents’ support of tourism. Journal of Travel Research, 43(2), 131–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2017.1357518

- Milman, A., & Pizam, A. (1988). Social impacts of tourism on central Florida. Annals of Tourism Research, 15(2), 191–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(88)90082-5

- Milman, A., Reichel, A., & Pizam, A. (1990). The impact of tourism on ethnic attitudes: The Israeli- Egyptian case. Journal of Travel Research, 29(2), 45–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728759002900207

- Ming, H. (2018). Cross-cultural differences and cultural stereotypes in Tourism Chinese Tourists in Thailand. 5.

- Moscovici, S. (1984). The phenomenon of social representations. In R. M. Farr, & S. Moscovici (Eds.), Social representations (pp. 3–69). Cambridge University Press.

- Ngowi, R. E., & Jani, D. (2018). Residents’ perception of tourism and their satisfaction: Evidence from Mount Kilimanjaro, Tanzania. Development Southern Africa, 35(6), 731–742. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2018.1442712.

- Nunkoo, R., & Gursoy, D. (2012). Residents’ support for tourism: An identity perspective. Annals of Tourism Research, 39(1), 243–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2011.05.006

- Nunkoo, R., & Ramkissoon, H. (2010). Gendered theory of planned behaviour and residents’ support for tourism. Current Issues in Tourism, 13(6), 525–540. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500903173967

- Nunkoo, R., & Ramkissoon, H. (2011). Developing a community support model for tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(3), 964–988. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2011.01.017

- Pearce, P. L. (1982). Tourists and their hosts: Some social and psychological effects of inter-cultural contact. In S. Bochner (Ed.), Cultures in contact studies in cross-cultural interaction (pp. 199–221). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-025805-8.50017-2

- Pearce, P. L., & Wu, M.-Y. (2016). Introduction: Meeting Asian tourists. In P. L. Pearce, & M.-Y. Wu (Eds.), Bridging tourism theory and practice (Vol. 7 (pp. 1–19). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S2042-144320160000007001

- Perdue, R. R., Long, P. T., & Allen, L. (1990). Resident support for tourism development. Annals of Tourism Research, 17(4), 586–599. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(90)90029-Q

- Pizam, A. (1978). Tourism’s impacts: The social costs to the destination community as perceived by its residents. Journal of Travel Research, 16(4), 8–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728757801600402

- Prayag, G., Hosany, S., Nunkoo, R., & Alders, T. (2013). London residents’ support for the 2012 Olympic games: The mediating effect of overall attitude. Tourism Management, 36, 629–640. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.08.003

- Rasoolimanesh, S. M., Ali, F., & Jaafar, M. (2018). Modeling residents’ perceptions of tourism development: Linear versus non-linear models. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 10, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2018.05.007

- Rasoolimanesh, S. M., Jaafar, M., Kock, N., & Ramayah, T. (2015). A revised framework of social exchange theory to investigate the factors influencing residents’ perceptions. Tourism Management Perspectives, 16, 335–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2015.10.001

- Rasoolimanesh, S. M., & Jaafar, M. (2016). Residents’ perception toward tourism development: A pre-development perspective. Journal of Place Management and Development, 9(1), 91–104. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMD-10-2015-0045

- Reisinger, Y., & Turner, L. W. (2003). Cross-cultural behaviour in tourism: Concepts and analysis. Elsevier.

- Ribeiro, M. A., Pinto, P., Silva, J. A., & Woosnam, K. M. (2017). Residents’ attitudes and the adoption of pro-tourism behaviours: The case of developing island countries. Tourism Management, 61, 523–537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.03.004

- Rivera, M., Croes, R., & Lee, S. H. (2016). Tourism development and happiness: A residents’ perspective. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 5(1), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2015.04.002

- Sheldon, P. J., & Var, T. (1984). Resident attitudes to tourism in North Wales. Tourism Management, 5(1), 40–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/0261-5177(84)90006-2

- Shen, J., D’Netto, B., & Tang, J. (2010). Effects of human resource diversity management on organizational citizen behaviour in the Chinese context. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 21(12), 2156–2172. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2010.509622

- Sirakaya-Turk, E., Nyaupane, G., & Uysal, M. (2014). Guests and hosts revisited: Prejudicial attitudes of guests toward the host population. Journal of Travel Research, 53(3), 336–352. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287513500580

- Stylidis, D. (2018). Place attachment, perception of place and residents’ support for tourism development. Tourism Planning & Development, 15(2), 188–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2017.1318775

- Stylidis, D., Biran, A., Sit, J., & Szivas, E. M. (2014). Residents’ support for tourism development: The role of residents’ place image and perceived tourism impacts. Tourism Management, 45, 260–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.05.006

- Su, L., & Swanson, S. R. (2020). The effect of personal benefits from, and support of, tourism development: The role of relational quality and quality-of-life. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(3), 433–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1680681

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2006). Using multivariate statistics (5th ed.). Pearson Education.

- TÜİK (Turkish Statistical Institute). (2020). Total population. https://cip.tuik.gov.tr/

- Tomljenovic, R. (2010). Tourism and intercultural understanding or contact hypothesis revisited. In O. Moufakkir & I. Kelly (Eds.), Tourism, Progress and peace (pp. 17–34). CABI Pub.

- Tosun, C. (2002). Host perceptions of impacts. Annals of Tourism Research, 29(1), 231–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(01)00039-1

- Tosun, C., & Timothy, D. J. (2001). Shortcomings in planning approaches to tourism development in developing countries: The case of Turkey. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 13(7), 352–359. https://doi.org/10.1108/09596110110403910

- UNWTO. (2019). International tourism highlights. https://www.unwto.org/publication/international-tourism-highlights-2019-edition

- Uriely, N., Maoz, D., & Reichel, A. (2009). Israeli guests and Egyptian hosts in Sinai: A bubble of serenity. Journal of Travel Research, 47(4), 508–522. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287508326651

- Vargas-Sánchez, A., Porras-Bueno, N., & Plaza-Mejía, M. de los Á. (2011). Explaining residents’ attitudes to tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(2), 460–480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2010.10.004

- WTTC. (2020). Economic impact report. https://wttc.org/en-gb/Research/Economic-Impact

- Yoon, Y., Gursoy, D., & Chen, J. S. (2001). Validating a tourism development theory with structural equation modeling. Tourism Management, 22(4), 363–372. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(00)00062-5

- Yuzhanin, S., & Fisher, D. (2016). The efficacy of the theory of planned behavior for predicting intentions to choose a travel destination: A review. Tourism Review, 71(2), 135–147. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-11-2015-0055