ABSTRACT

Ecotourism is increasingly being adopted to improve the livelihoods of local communities and fulfill conservation goals. Many critical actors, including but not limited to governments and conservation organizations, believe that for ecotourism to be successful, local communities must appreciate and support wildlife conservation activities. Without evidence that communities’ value systems are oriented in a manner that aligns with the authorities’ sustainable development and wildlife conservation ideologies, strategies for how to achieve the most benefits for the most people will be based on anecdotes and assumptions. This study investigated residents’ value orientation towards wildlife in the context of Bardia National Park (BNP), Nepal. We surveyed residents from eight buffer zone communities surrounding BNP with a human–wildlife conflict (n = 871). Our findings revealed four distinct clusters of resident WVOs, creating challenges for BNP ecotourism development. Socio-demographic and resource management factors also play critical roles in shaping the sustainable development of BNP ecotourism.

Introduction

Ecotourism is a popular and universally adopted segment of the tourism industry (Fennell, Citation2020). The term “ecotourism” is often used alongside terms such as “protected area” (PA) tourism or “nature-based tourism” and touted to be the fastest-growing segment of the tourism industry (Das & Chatterjee, Citation2015). Ecotourism’s impacts on conservation, economic development, and societal wellbeing vary in degrees of success and failure (Cobbinah et al., Citation2017; Coria & Calfucura, Citation2012; Wondirad, Citation2019). For better or worse, ecotourism’s contributions toward achieving the sustainable development goals have embedded this segment of tourism into economies and the human experience (Honey, Citation2008; Nahuelhual et al., Citation2013).

The popularity of ecotourism as a local economic development and wildlife conservation strategy (Bell, Citation1987) has brought an increasing number of humans into proximity with wildlife. With increased wildlife conservation efforts, communities engaged in PA ecotourism may be subject to elevated, novel, and intense interactions with livestock predation or attacks by wildlife (Distefano, Citation2005; Gusset et al., Citation2009). Human–wildlife conflict (HWC) is of global concern and is defined as negative interactions between humans and wildlife or between humans concerning wildlife and is exacerbated around PAs (Peterson et al., Citation2010). For sustainable development strategies to achieve both human development and biodiversity conservation targets, the frequency of and ability to mitigate or solve HWCs resulting from ecotourism is critical.

Balancing the needs of humans and the wellbeing of wildlife can pose unique challenges to PA tourism development because these are inherently contradictory goals. For instance, previous research demonstrates that persistent HWC and the inability of authorities to address it can lead to unacceptable costs and conflict, and, ultimately, dissatisfaction or dissent among locals (Barua et al., Citation2013; Bello et al., Citation2017; Snyman, Citation2014; Walpole & Thouless, Citation2005). Moreover, negative outcomes, such as lost economic opportunities (Hackel, Citation1999), may influence locals’ interactions with tourists and the ecotourism development process. Researchers also suggest that top-down approaches, characteristic of PA governance and ecotourism development, can lead to disharmony within and dissent among communities, as authorities have a history of prioritizing wildlife conservation over local wellbeing (e.g. Mir et al., Citation2015; Morais et al., Citation2018). Structural prejudices aside, bankrolling actors hold fast to the idea that they can balance human and wildlife needs by ensuring a more equitable distribution of ecotourism benefits and enacting deliberative approaches to integrate local values, beliefs, and attitudes into PA decision-making and solving HWCs (Morais et al., Citation2015; Snyman & Bricker, Citation2019; Spiteri & Nepal, Citation2008).

Researchers have demonstrated the difficulty of balancing rural livelihoods with PA conservation in Nepal. Sharma (Citation1990) outlined the tenets of a long-term strategy to balance subsistence livelihoods in the Chitwan National Park region, emphasizing the need to see PAs as not merely a geographic space but also a cultural one, made alive by the customary rights and activities occurring within that space. Nepal and Weber (Citation1995) were also early researchers to problematize park–people dynamics, expressing the need for authorities to respect existing and sustainable nature–culture relations and espouse participatory, financial, and educational strategies to ameliorate value conflicts. The Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation (Citation1999) later adopted the buffer zone concept to help locals to regain aspects of their livelihoods disrupted by PA creation. Researchers have declared that buffers zones and ecotourism now underpin top-down policies to link the disjointed aims of human wellbeing and wildlife conservation (Nyaupane & Poudel, Citation2011). Nonetheless, the paradigm is not foolproof. Spiteri and Nepal (Citation2008) examined incentive-based programs in Chitwan National Park and concluded that the costs and benefits accrued by the residents differed, in that specific communities in proximity to touristic areas were receiving more benefits. KC et al. (Citation2018) similarly noted the role of geospatial patterns in describing asymmetrical distribution of ecotourism’s costs, benefits, and varying levels of success. In summary, the schism between costs and benefits may be framed in terms of the value conflict introduced by ecotourism development policies (Lai & Nepal, Citation2006). Though wildlife is paramount to PA tourism in Nepal, researchers have yet to fully map residents’ values orientation towards wildlife, which may further elucidate another important dimension for addressing the aforementioned schism.

Wildlife value orientation (WVO) studies are a powerful theoretical approach to identify patterns in human–wildlife relationships and predict human behavior towards wildlife in certain situations (Cerri et al., Citation2017; King & Nair, Citation2013). The conceptual approach is situated within the cognitive hierarchy and formalizes the research of Steinhoff (Citation1980) and others who have explored human value orientations toward wildlife as well as the occurrence of clustering values (e.g. Stern et al., Citation1995). Bright et al. (Citation2000) noted that WVOs can help managers understand the ways in which humans relate to wildlife, evaluate policy, estimate demands for wildlife-related activities, and communicate with target populations about wildlife policy and recreation opportunities. Most WVO studies have focused on understanding how residents and managers relate to wildlife in North America (Manfredo et al., Citation2020), but studies have been expanding into novel, cross-cultural contexts and across stakeholder groups (e.g. Gamborg et al., Citation2019; Zainal Abidin & Jacobs, Citation2016; Zinn & Shen, Citation2007).

Research suggests that eliciting WVOs in the context of PA ecotourism can help decision-makers to better understand how tourism communities relate and react to wildlife (e.g. Manohar et al., Citation2012; Needham, Citation2010; Serenari et al., Citation2015). Understanding resident orientations towards wildlife in an ecotourism context is important because if WVOs are not oriented in a direction that aligns with wildlife conservation goals, the resultant dissent can yield failure to achieve desired targets (Bright et al., Citation2000; Teel et al., Citation2010; Teel & Manfredo, Citation2010). Certain orientations towards wildlife among communities can create either favorable or undesirable contexts or outcomes for ecotourism development (Manohar et al., Citation2012). A review of the literature revealed that there is a paucity of research investigating the linkages between ecotourism, WVOs, and HWC or how they diverge and align among different groups of people (e.g. Manohar et al., Citation2012). Our examination of the literature revealed a research focus on two of the three domains, though the third was still relevant (e.g. Freeman et al., Citation2021), or focuses on using tourist WVOs to characterize interactions with wildlife (e.g. Harvey Lemelin & Smale, Citation2007).

We aim to address this need by conducting a case study in Nepal, where ecotourism activities are rising while HWC remains an ongoing problem (LeClerq et al., Citation2019). Specifically, we investigate the factors influencing the WVOs of residents living near Bardia National Park (BNP), a cornerstone of the Nepal PA network and one of the largest and most popular parks in the country, but also dealing with rising HWC. The success of ecotourism policy hinges upon the mitigation of HWC. This study aims to (i) identify distinct clusters of residents based on their value orientation towards wildlife and how their value orientation differs among the clusters, (ii) examine the differences among the clusters for value orientation towards wildlife and resource management factors, and (iii) examine the differences among clusters regarding socio-demographic variables.

Wildlife value orientations

Grounded in social psychology, WVOs capture individual and collective wildlife-related experiences (Fulton et al., Citation1996). WVOs have become a popular conceptual and methodological approach for understanding and managing human–wildlife interactions and bolstering the inclusion of wildlife stakeholder expectations (Clark et al., Citation2017). WVOs do not reflect utility theory and the material value of wildlife. Instead, because they are situated at the bottom of the cognitive hierarchy, they reflect human thought. Values drive behavior, reflect desirable ends states and worldview, and anchor lower-order cognitions such as attitudes and beliefs (Rokeach, Citation1973). As is common with values, they change gradually but tend to remain stable (Ford-Thompson et al., Citation2015) and are influenced by contextual, multi-level factors (Manfredo et al., Citation2020).

WVOs can be viewed as positive and negative (Cerri et al., Citation2017), and parsed into four distinct categories to segment and analyze the subjects’ values towards wildlife. The WVO literature suggests that mutualism and domination are dominant WVOs, but the concept also includes pluralist and distanced orientations. Recent research has further broken down WVOs into high/low categories (Gamborg & Jensen, Citation2016). Survey items measuring mutualism prioritize living in harmony with wildlife and elevating wildlife existence and wellbeing to a level parallel to that of humans. Meanwhile, domination-oriented subjects tend to relate to wildlife in a manner that prioritizes human needs, using wildlife for human purposes, and hands-on (e.g. lethal management) strategies to moderate human–wildlife interactions (Jacobs et al., Citation2014). Pluralism reflects a mix of mutualist and domination orientations, while a distanced orientation reflects limited engagement with either (Teel & Manfredo, Citation2010; Vaske et al., Citation2011).

Studies of WVOs have revealed critical insights as societies change and move away from rural livelihoods and utilitarian values and towards urbanization, deliberative institutional arrangements in wildlife conservation, and their implications for human wellbeing and biodiversity conservation (Manfredo et al., Citation2020; Teel & Manfredo, Citation2010). For instance, studies demonstrate the value of integrating various knowledge and spatial considerations into decision-making (Bright et al., Citation2000; Laverty et al., Citation2019), ways to improve communications about interactions with wildlife (Miller et al., Citation2018), policy preferences regarding species management (Serenari et al., Citation2015; Sijtsma et al., Citation2012), and the role of household dynamics in shaping WVOs (Clark et al., Citation2017; Zinn et al., Citation2002).

Research has revealed important predictors of reaction and behaviors within explorations of the WVO–HWC nexus, particularly in subsistence communities and working land contexts. Policy preferences are also popular variables of interest because they have a direct influence on outcomes. Researchers tend to measure support for or acceptability of management actions as a function of WVOs and how those dynamics impact the likelihood of living peaceably with wildlife (Bruskotter et al., Citation2017; Knackmuhs et al., Citation2019; Whittaker et al., Citation2006). Cerri et al. (Citation2017) revealed that select species may be the target of individuals with a domination orientation, while a mutualist orientation can apply to a wide range of animals rather than just a single species. Capacity studies are also important to WVO research. These studies may examine knowledge, political or religious affiliations, and related variables (Zainal Abidin & Jacobs, Citation2016). Bright et al. (Citation2000) noted that the knowledge capacity of segments of the public is critical to raise awareness about and support wildlife conservation and interactions. Demographics are also an important variable of interest in this context (Vaske et al., Citation2011) and a focal area of many WVO studies (e.g. Zinn & Pierce, Citation2002 (gender); Clark et al., Citation2017 (age); Manfredo et al., Citation2020 (place of residency, rural–urban)).

Methodology

Study context

In Nepal, the history of PA development and the conservation of wildlife and natural resources started in 1973 with the establishment of the Chitwan National Park. Since then, Nepal has increased its number of PAs and upped conservation priorities in the country, with about 25% of the surface area of the country allocated to PAs (Department of National Park and Wildlife Conservation (DNPWC), Citation2019). A total of 165,304 tourists visited the Nepal PAs in 2005–2006, and the number increased by 327.18% to 706,148 in 2018–2019 (DNPWC, Citation2017, Citation2019). Even though PAs were increasingly becoming a primary conservation tool for Nepal, the country only recognized the livelihood dependency on natural resources of communities surrounding PAs in the mid-1990s. Locals were regularly subject to HWC. As part of a comprehensive state strategy to mitigate park–people conflict, authorities established buffer zones to facilitate natural resource-dependent livelihoods. Gradually, ecotourism initiatives were introduced to incentivize communities living in the buffer zone and to tap into the growing ecotourism market. These ecotourism projects are promoted in PA settings to support local communities and improve their economic and social wellbeing.

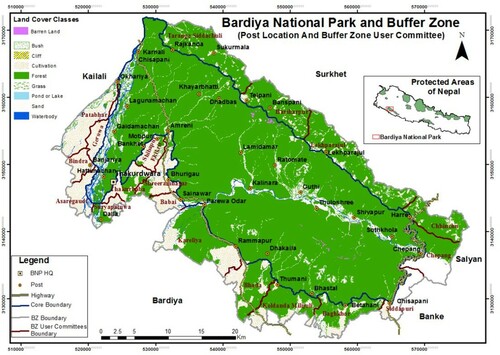

Ecotourism prospects are growing faster in the BNP than the average growth rates in most PAs in Nepal. In the periods of 2005–2006 and 2018–2019, tourist visitation to the BNP increased by 1,661.69% (DNPWC, Citation2017, Citation2019). While the BNP is one of the largest PAs in the Terai region of Nepal, covering an area of 968 km2 (), over the years the BNP has undergone a series of shifts in name, size, and conservation regulations (Thapa Karki, Citation2013). Even though BNP was established in 1976, the buffer zone area of 507 km2 was added only in 1996 to support the livelihoods of resource-dependent communities (DNPWC, Citation2019). Local communities rely on subsistence agriculture and forest resources such as timber, firewood, and fodder. Subsistence agriculture is only able to support 42% of households of the local communities (Bhattarai & Fischer, Citation2014). There are 19 buffer zone communities in the BNP (). Thapa Karki (Citation2013) reported that 30–50% of the revenue generated from the park is invested in the community development of the buffer zone areas. However, the distribution of revenue is often considered unfair (Allendorf et al., Citation2007; Thing et al., Citation2017). Recently, park authorities and WWF Nepal have been promoting community-based homestays to support rural livelihoods (KC, Citation2021).

Figure 1. Bardia National Park and buffer zone communities (source: BNP, Citation2020).

Data collection

The study design was approved by the University of North Texas Institutional Review Board (IRB) (Study# IRB-19-187). The research team also acquired a research permit from the DNPWC and subsequently from the BNP authority in Nepal. Based on consultations with BNP officials, who know the issues and region best, we selected eight of the 19 buffer zone communities for data collection based on the number of reported HWC cases and compensation requests submitted to park authorities (). We used a stratified random sampling technique (Paudyal et al., Citation2018) to ensure the equal representation of the communities. We allocated 110 questionnaires to each community, ensuring that at least 5% of households were represented in the study (resulting in a total of 871 usable survey questionnaires): Patabhar (n = 110), Geruwa (n = 110), Bindra (n = 105), Asaregaudi (n = 107), Shivapur Ekikrit (n = 110), Shreeramnager (n = 109), Thakurbaba (n = 110), and Suryapatuwa (n = 110) ().

Table 1. Selected buffer zone user committees and their demographic information (source: DNPWC, Citation2016).

We surveyed the heads of households first, then recruited another household adult who was at least 18 years of age when the head of the household was not available during the month of July in 2019. The first author, a native of Nepal, and Nepalese field assistants collected the data while the field assistants were provided training before the data collection to familiarize them with the questionnaire and its content. The research team filled out the questionnaire on behalf of the participants. The importance of the study and potential practical implications resulting from the study were briefly explained prior to administering the survey, and the respondents were not compensated for their participation. We maintained flexible hours (early morning to evening) to increase our chances of meeting participants during what was the monsoon season as well as a period of high agricultural activity.

Measurement items and data analysis

We adapted the survey instrument items from Cerri et al. (Citation2017) to measure the WVOs. We contextualized and situated wildlife resource management statements within the primary domains of interest in the PA literature. The items were not mutually exclusive and some overlap between domains was expected. We situated the survey items under the areas of knowledge, tourism benefits, conservation motivation, enforcement policies, and governance. We assessed legal awareness (Macura et al., Citation2011; Studsrød & Wegge, Citation1995; Thing et al., Citation2017) and potential for under-reporting (Gillingham & Lee, Citation2003; Pant et al., Citation2016). PA tourism is imbued with potential costs and benefits to local livelihoods. We explored these outcomes for communities, families, and individuals (Allendorf et al., Citation2007; LeClerq et al., Citation2019; Thapa Karki, Citation2013) and their preference for strategies to overcome existing HWCs—specifically, compensation (Bhatta et al., Citation2010; Karanth & Nepal, Citation2012), incentives (Shova & Hubacek, Citation2011), and deliberative arrangements (Thing et al., Citation2017). We also explored internal motivators known to influence views and behavior—specifically, identity as a resource steward (Bennett et al., Citation2012) and moral orientations regarding the degree to which locals agree they should shoulder the burden of conservation (Seeland, Citation2000), overall support for wildlife conservation (Allendorf, Citation2007), and implementing a penal code (Jana, Citation2007; Kahler & Gore, Citation2012). We also explored the role communities should have in decision-making. We used a five-point Likert scale ranging from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree for all the WVO measurement items.

We performed a two-step cluster analysis to group the residents with similarities (Pesonen & Tuohino, Citation2017). Cluster analysis measures distances and homogeneity among groups and suggests the ideal number of clusters (Kaufman & Rousseeuw, Citation2005). The mutualist group holds a high priority towards social affiliation and caring beliefs compared to appropriate use and hunting beliefs (Teel & Manfredo, Citation2010). Due to their high inclination towards mutualism, they are likely to support ecotourism development because it is consistent with their beliefs. A disinterested cluster does not have a penchant for either mutualistic or domination WVOs. As they do not hold either a mutualism or a domination orientation, this indicates a low level of interest in wildlife and wildlife issues (Teel & Manfredo, Citation2010). Usually, a cluster with a high score on every WVO is defined as “pluralist”, as they echo both domination and mutualism aspects (Teel & Manfredo, Citation2010). In our study, this group represents a balance, except that their hunting belief is the lowest among all the clusters. Their hunting belief is consistent with the current conservation policies (i.e. strict regulation without any privilege for wildlife consumption), but they also support the appropriate use belief. Therefore, instead of pluralist, they are referred to as conscious. The antagonistic group prioritizes human needs (i.e. the use of wildlife). Usually, a cluster with a high domination score and a low mutualism score is referred to as “traditionalist”. This group may lack affection for wildlife (Jacobs et al., Citation2014). Thus, this cluster is referred to as antagonistic as opposed to traditionalist because they will favor hunting.

We examined the reliability and validity of the measurements through factor analysis and confirmatory factor analysis using AMOS 26.0. We retained items exceeding a Cronbach’s alpha score of at least 0.70 for each construct and the goodness-of-fit indices exceeded the recommended values (CMIN/DF < 2.00, GFI > .90, CFI > .90, and RMSEA > .50) (Arbuckle, Citation2019). We employed two-step cluster analysis with hierarchical and K-means cluster analyses using SPSS version 24 to identify the optimal number of clusters. We verified the suggested number of clusters from the analysis with a dendrogram structure (Kaufman & Rousseeuw, Citation2005). Further, we performed one-way ANOVA and chi-square analyses to examine the differences among clusters .

Table 2. Reliability test of wildlife value orientations.

Results

We collected 871 valid survey questionnaires from households within the buffer zone. Among the respondents, 54% were males and 46% were females. A majority (50.1%) of the respondents were between 30 and 50 years of age, and more than half (55.5%) of the respondents reported primary education as their highest education level ().

Table 3. Demographic information.

The analysis revealed that four clusters were ideal for the current study. One-way ANOVA and chi-square analyses used to examine the differences among clusters were found to be statistically significant at a .01 alpha level in relation to the participants’ WVOs, resource management factors, and demographic characteristics. As a result, the data were grouped into four clusters based on the participants’ WVOs and labeled based on their characteristics: cluster 1 (n = 258), cluster 2 (n = 269), cluster 3 (n = 225), and cluster 4 (n = 119). Dolnicar et al. (Citation2014) indicates that the threshold of a 70 sample size for each cluster is ideal to find the maximum differences among clusters and achieve valid results.

Less than one third (29.6%) of the participants were classified into cluster 1 (n = 258) (). Cluster 1 showed above-average mean scores for social affiliation and caring beliefs compared to other clusters identified in the study. The mean score for the appropriate use belief was below the mid-point (3) of the scale, and the score was the lowest compared to the other clusters. Additionally, the score for the hunting belief was below the mid-point (3) of the scale. Therefore, cluster 1 was labeled as “mutualist” after these characteristics. Cluster 2 accounted for 30.9% of the sample, representing the largest share among the clusters. The group showed below the mid-point (3) of the scale for hunting belief and was closer to the neutral rating for the other value orientation beliefs, thus the group was labeled as “disinterested”. Cluster 3 represented over one fourth (25.8%) of the sample and showed generally positive and higher than average scores in all the value orientation beliefs. However, the group had the lowest mean score for hunting belief. Therefore, this cluster was categorized as “conscious”, as their value orientation beliefs recognized the appropriate use belief along with the social affiliation and caring beliefs, but did not support the hunting belief. Cluster 4 had the smallest share of the sample (13.7%) among the clusters, but this group’s appropriate use belief was the strongest among the clusters. This group also showed the lowest social affiliation and caring beliefs among the clusters. The mean score for the hunting belief was the highest among the cluster, even though the mean score was close to neutral. Overall, residents’ strong support for the appropriate use belief and neutrality for the hunting belief while maintaining disagreement for social affiliation and caring beliefs indicate their conflicting relationships with wildlife. Thus, this cluster was characterized as “antagonistic”.

Table 4. Wildlife value orientation clustering.

To investigate the factors that characterized each cluster, their knowledge of wildlife rules and regulations, perceived benefits of tourism, conservation motivation, and opinions regarding enforcement policies and conservation governance were analyzed (). Compared to the other clusters, clusters 1 (mutualist) and 3 (conscious) appeared to show more positive ratings on all the items shown in the table. Cluster 1 (mutualist) had the highest mean score for knowledge of wildlife rules and regulations and opinions on enforcement policies, whereas cluster 3 (conscious) placed the highest rating on conservation motivation and conservation governance. Furthermore, cluster 2 (disinterested) showed relatively moderate mean scores on most of the items, but perceived enforcement policies were rated lowest compared to the other clusters. Cluster 4 (antagonistic) placed the lowest rating on tourism benefits, conservation motivation, and conservation governance among the clusters.

Table 5. Resource management factors clustering.

Additional demographic characteristics for the clusters are shown in . Cluster 1 (mutualist) appears to be young, male, educated, and reported the highest annual income and landholding size compared to other clusters. Cluster 2 (disinterested) can be described as older and less educated compared to the other groups. In particular, this group reported the lowest landholding size and least damage from wildlife, as well as the highest satisfaction with compensation. Cluster 3 (conscious) is characterized as being female-dominant and having the least annual income and the highest damage from wildlife compared to the other clusters. The group’s satisfaction mean score with compensation was the lowest when compared to the other groups. Cluster 4 (antagonistic) can be described as a female-dominant and less educated group compared to the other clusters. The group had a relatively low annual income and satisfaction with compensation and high damage from wildlife. The results from one-way ANOVA and chi-square analyses revealed that the differences among clusters in terms of variables shown in the tables were statistically significant at the .01 alpha level.

Table 6. Socio-demographic characteristics clustering.

Discussion and conclusions

Ecotourism development in the BNP will likely succeed if younger generations are supportive of the government’s aim to achieve a participatory but authoritative approach. Our results revealed that mutualists tended to be younger, male, and held more natural and financial capital. They were also well informed about wildlife laws and regulations and supportive of enforcement policies. Youths were reported to be actively involved in conservation activities conducted by the BNP officials (KC, Citation2021). Hence, operating under a dynamic of government-led deliberative PA ecotourism development, youths would have the opportunity to see the value of a democratic but highly regulated ecotourism milieu to minimize negative impacts (Weaver, Citation2000), and recognize and appreciate the tradeoffs that come with embracing a sustainable PA ecotourism program. Likewise, officials can use these results to recognize the gaps in their community engagement strategies. Large portions of our sample will have different levels of understanding, capital, engagement, motivations, and caring when it comes to BNP ecotourism.

For instance, a continued lack of support or exclusion from ecotourism or related conservation programs could further alienate those who are disinterested in or antagonistic towards either wildlife conservation or BNP tourism. This group reported less total damage, but they also held the lowest landholding size and were relatively unhappy with the compensation (unhappy or neutral), further suggesting that the existing compensation program has not been well-received (KC, Citation2021). Elevated damage from wildlife to communities dependent on subsistence agriculture perhaps led to this disassociation or resentment (Bhattarai & Fischer, Citation2014). A timely and transparent compensation program could potentially help mitigate HWC while minimizing the residents’ antagonistic and uncooperative attitudes (Bello et al., Citation2017). A buffer zone management plan stipulates the provision to return 30–50% of the income earned by PAs to community-development and income-generating activities for residents (Aryal et al., Citation2019; Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation, Citation1999). A provision of benefit-sharing mechanisms allows avenues to garner support for ecotourism development (Hunt et al., Citation2015; Snyman & Bricker, Citation2019; Umar & Kapembwa, Citation2020). Our data suggest that critical actors such as state and park officials should consider designing and administering community engagement programs that encourage broader participation and involvement in BNP ecotourism initiatives. Our findings can inform the use of a wider lens to appeal to a range of WVOs and demographic profiles to better integrate locals who feel alienated from the larger development process (Paudyal et al., Citation2018). As such, these programs will need to effectively demonstrate that the costs do not outweigh the benefits to appeal to the wide range of WVOs (Hackel, Citation1999).

To appeal to the female-majority conscious cluster, ecotourism in the BNP region will need to provide an opportunity to earn income from the existence of wildlife while mitigating HWC or compensating this group for wildlife damage. Wildlife conservation motivation is high among this group, and they may be willing to make a livelihood adjustment to benefit wildlife conservation efforts but require support to do so. Residents within this group may be the most approachable, particularly by state officials whom they seem to respect. This group might be effective in critical roles to address HWC and ecotourism development issues because they appear to approach HWC with a level-headed approach and recognize that a balance between human and wildlife wellbeing is required for park tourism to work for everyone.

Ecotourism development and wildlife conservation will encounter resistance from antagonistic types. This group is a female-dominant group and had among the least formal education and income levels, high damage from wildlife, and low satisfaction with compensation. These residents may be motivated to compromise by dramatically reduced wildlife damage and increased material benefits attached to ecotourism development. These domination-types holding antagonistic and uncooperative attitudes (Bello et al., Citation2017) are likely to change their values and attitudes towards wildlife and conservation efforts with the provision of benefit-sharing mechanisms (Snyman & Bricker, Citation2019) and the effective implementation of community-oriented buffer management plan (Aryal et al., Citation2019; Thapa Karki, Citation2013). As changing human values is difficult (Rokeach, Citation1973) and they underpin support for wildlife management (St John et al., Citation2019) and ecotourism development (Fletcher, Citation2009), research should further investigate what policy arrangements are viable for as many locals as possible.

Before the introduction of the buffer zone in 1996 (Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation, Citation1999), HWC and residents’ resentments of park authority could be characterized as severe. The establishment of the buffer zone and expansion of community forestry programs in surrounding buffer zone communities increased access to resources and addressed HWC to some extent (Thapa Karki, Citation2013). Moreover, due to the popularity of ecotourism in a few national parks and conservation areas such as Chitwan National Park, Mt. Everest National Park, and Annapurna Conservation Area, the benefits accrued from ecotourism development also helped mitigate the conflicts and support conservation goals (Nyaupane & Poudel, Citation2011). However, benefits have often been reaped by gateway communities and those with the most capital (KC et al., Citation2018; Spiteri & Nepal, Citation2008). Therefore, planning for ecotourism development ideally requires a holistic approach without any bias for geographical locations to achieve the equitable distribution of ecotourism benefits and mitigated HWC. Specifically, communities with high HWC incidents and wildlife damage and without the means to help themselves should be prioritized in the planning of PA ecotourism development.

HWC issues continue to dominate PAs around the world (Peterson et al., Citation2010). This study reiterates that WVOs studies are necessary to inform the tourism development process and, hopefully, promote more sustainable outcomes. Community development and educational programs may be made more effective based on the insight gained from empirical studies on WVOs. As ecotourism development is still intricately associated with PA conservation, understanding residents’ orientation towards wildlife, their perception of resource management aspects, and their socio-demographic factors create opportunities to implement effective strategies and ensure that the time, energy, and resources (e.g. financial, human) invested in conservation efforts produce positive outcomes. Ecotourism promises to foster sustainable destination development, which remains a questionable goal for the most part with limited success stories, while it has been argued that this goal is used as a marketing tactic (Wondirad, Citation2019). Every aspect that potentially compromises the success of PA ecotourism projects should be considered in the planning and development of ecotourism.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allendorf, T. D. (2007). Residents’ attitudes toward three protected areas in southwestern Nepal. Biodiversity and Conservation, 16(7), 2087–2102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-006-9092-z

- Allendorf, T. D., Smith, J. L., & Anderson, D. H. (2007). Residents’ perceptions of Royal Bardia National Park, Nepal. Landscape and Urban Planning, 82(1-2), 33–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2007.01.015

- Arbuckle, J. L. (2019). Amos 26.0 user's guide. IBM SPSS.

- Aryal, C., Ghimire, B., & Niraula, N. (2019). Tourism in protected areas and appraisal of ecotourism in Nepalese policies. Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Education, 9, 40–73. https://doi.org/10.3126/jthe.v9i0.23680

- Barua, M., Bhagwat, S. A., & Jadhav, S. (2013). The hidden dimensions of human–wildlife conflict: Health impacts, opportunity and transaction costs. Biological Conservation, 157, 309–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2012.07.014

- Bell, R. H. (1987). Conservation with a human face: Conflict and reconciliation in African land use planning. In D. Anderson, & R. H. Grove (Eds.), Conservation in Africa: People, policies and practice (pp. 79–101). Cambridge University Press.

- Bello, F. G., Lovelock, B., & Carr, N. (2017). Constraints of community participation in protected area-based tourism planning: The case of Malawi. Journal of Ecotourism, 16(2), 131–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2016.1251444

- Bennett, N., Lemelin, R. H., Koster, R., & Budke, I. (2012). A capital assets framework for appraising and building capacity for tourism development in aboriginal protected area gateway communities. Tourism Management, 33(4), 752–766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2011.08.009

- Bhatta, L. D., Koh, K. L., & Chun, J. (2010). Policies and legal frameworks of protected area management in Nepal. In L. H. Lye, V. Savage, & G. Ofori (Eds.), Sustainability matters: Environmental Management in Asia (pp. 157–188). World Scientific Publishing Company.

- Bhattarai, B. R., & Fischer, K. (2014). Human–tiger Panthera Tigris conflict and its perception in Bardia National Park, Nepal. Oryx, 48(4), 522–528. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605313000483

- BNP. (2020). Annual report. Bardia National Park Office, Thakurdwara, Bardia, Nepal.

- Bright, A. D., Manfredo, M. J., & Fulton, D. C. (2000). Segmenting the public: An application of value orientations to wildlife planning in Colorado. Wildlife Society Bulletin, 28(1), 218–226. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4617305

- Bruskotter, J. T., Vucetich, J. A., Manfredo, M. J., Karns, G. R., Wolf, C., Ard, K., Carter, N. H., López-Bao, J. V., Chapron, G., Gehrt, S. D., & Ripple, W. J. (2017). Modernization, risk, and conservation of the world's largest carnivores. BioScience, 67(7), 646–655. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/bix049

- Cerri, J., Mori, E., Vivarelli, M., & Zaccoroni, M. (2017). Are wildlife value orientations useful tools to explain tolerance and illegal killing of wildlife by farmers in response to crop damage? European Journal of Wildlife Research, 63(70), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10344-017-1127-0

- Clark, K. E., Cupp, K., Phelps, C. L., Peterson, M. N., Stevenson, K. T., & Serenari, C. (2017). Household dynamics of wildlife value orientations. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 22(5), 483–491. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871209.2017.1345022

- Cobbinah, P. B., Amenuvor, D., Black, R., & Peprah, C. (2017). Ecotourism in the kakum conservation area, Ghana: Local politics, practice and outcome. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 20, 34–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jort.2017.09.003

- Coria, J., & Calfucura, E. (2012). Ecotourism and the development of indigenous communities: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Ecological Economics, 73, 47–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2011.10.024

- Das, M., & Chatterjee, B. (2015). Ecotourism: A panacea or a predicament? Tourism Management Perspectives, 14, 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2015.01.002

- Distefano, E. (2005). Human–wildlife conflict worldwide: a collection of case studies, analysis of management strategies and good practices. Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Sustainable Agriculture and Rural Development (SARD). https://www.tnrf.org/files/E-INFO-Human-Wildlife_Conflict_worldwide_case_studies_by_Elisa_Distefano_no_date.pdf

- DNPWC. (2016). Bardia National Park and its buffer zone management plan 2016-2020. Bardia National Park Office, Thakurduwara, Bardia, Nepal.

- DNPWC. (2017). Annual report. Department of National Park and Wildlife Conservation, Babarmahal, Kathmandu, Nepal.

- DNPWC. (2019). Annual report. Department of National Park and Wildlife Conservation, Babarmahal, Kathmandu, Nepal.

- Dolnicar, S., Grün, B., Leisch, F., & Schmidt, K. (2014). Required sample sizes for data-driven market segmentation analyses in tourism. Journal of Travel Research, 53(3), 296–306. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287513496475

- Fennell, D. A. (2020). Ecotourism. Routledge.

- Fletcher, R. (2009). Ecotourism discourse: Challenging the stakeholders theory. Journal of Ecotourism, 8(3), 269–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724040902767245

- Ford-Thompson, A. E., Snell, C., Saunders, G., & White, P. C. (2015). Dimensions of local public attitudes towards invasive species management in protected areas. Wildlife Research, 42(1), 60–74. https://doi.org/10.1071/WR14122

- Freeman, S., Taff, B. D., Miller, Z. D., Benfield, J. A., & Newman, P. (2021). Mutualism wildlife value orientations predict support for messages about distance-related wildlife conflict. Environmental Management, 67(5), 920–929. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-020-01414-1

- Fulton, D. C., Manfredo, M. J., & Lipscomb, J. (1996). Wildlife value orientations: A conceptual and measurement approach. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 1(2), 24–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871209609359060

- Gamborg, C., & Jensen, F. S. (2016). Wildlife value orientations among hunters, landowners, and the general public: A danish comparative quantitative study. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 21(4), 328–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871209.2016.1157906

- Gamborg, C., Stamati, S., & Jensen, F. S. (2019). Wildlife value orientations of prospective conservation and wildlife management professionals. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 24(5), 496–500. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871209.2019.1630694

- Gillingham, S., & Lee, P. C. (2003). People and protected areas: A study of local perceptions of wildlife crop-damage conflict in an area bordering the selous Game reserve, Tanzania. Oryx, 37(3), 316–325. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605303000577

- Gusset, M., Swarner, M. J., Mponwane, L., Keletile, K., & McNutt, J. W. (2009). Human wildlife conflict in northern Botswana: Livestock predation by endangered African wild dog Lycaon pictus and other carnivores. Oryx, 43(1), 67–72. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605308990475

- Hackel, J. D. (1999). Community conservation and the future of Africa's wildlife. Conservation Biology, 13(4), 726–734. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1739.1999.98210.x

- Harvey Lemelin, R., & Smale, B. (2007). Wildlife tourist archetypes: Are all polar bear viewers in Churchill, manitoba ecotourists? Tourism in Marine Environments, 4(2-3), 97–111. https://doi.org/10.3727/154427307784771986

- Honey, M. (2008). Ecotourism and sustainable development: Who owns paradise? Island Press.

- Hunt, C. A., Durham, W. H., Driscoll, L., & Honey, M. (2015). Can ecotourism deliver real economic, social, and environmental benefits? A study of the Osa peninsula, Costa Rica. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23(3), 339–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2014.965176

- Jacobs, M. H., Vaske, J. J., & Sijtsma, M. T. (2014). Predictive potential of wildlife value orientations for acceptability of management interventions. Journal for Nature Conservation, 22(4), 377–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnc.2014.03.005

- Jana, S. (2007). Voices from the margins: Human rights crises around protected areas in Nepal. Policy Matters, 15, 87–99. https://www.iucn.org/downloads/pm15.pdf

- Kahler, J. S., & Gore, M. L. (2012). Beyond the cooking pot and pocket book: Factors influencing noncompliance with wildlife poaching rules. International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice, 36(2), 103–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/01924036.2012.669913

- Karanth, K. K., & Nepal, S. K. (2012). Local residents perception of benefits and losses from protected areas in India and Nepal. Environmental Management, 49(2), 372–386. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-011-9778-1

- Kaufman, L., & Rousseeuw, P. (2005). Finding groups in data: An Introduction to cluster analysis. Wiley.

- KC, B. (2021). Ecotourism for wildlife conservation and sustainable livelihood via community-based homestay: A formula to success or a quagmire? Current Issues in Tourism, 24(9), 1227–1243. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1772206

- KC, B., Paudyal, R., & Neupane, S. S. (2018). Residents’ perspectives of a newly developed ecotourism project: As assessment of effectiveness through the lens of an importance-performance analysis. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 23(6), 560–572. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2018.1467938

- King, N., & Nair, V. (2013). Determining the wildlife value orientation (WVO): a case study of lower Kinabatangan, Sabah. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, 5(4), 377–387. https://doi.org/10.1108/WHATT-03-2013-0014

- Knackmuhs, E., Farmer, J., & Knapp, D. (2019). The relationship between narratives, wildlife value orientations, attitudes, and policy preferences. Society & Natural Resources, 32(3), 303–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2018.1517916

- Lai, P. H., & Nepal, S. K. (2006). Local perspectives of ecotourism development in Tawushan Nature reserve, Taiwan. Tourism Management, 27(6), 1117–1129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2005.11.010

- Laverty, T. M., Teel, T. L., Thomas, R. E. W., Gawusab, A. A., & Berger, J. (2019). Using pastoralists ideology to understand human-wildlife coexistence in arid agricultural landscapes. Conservation Science and Practice, 1(5), e35. https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.35

- LeClerq, A. T., Gore, M. L., Lopez, M. C., & Kerr, J. M. (2019). Local perceptions of conservation objectives in an alternative livelihoods program outside Bardia National Park, Nepal. Conservation Science and Practice, 1(12), e131. https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.131

- Macura, B., Zorondo-Rodríguez, F., Grau-Satorras, M., Demps, K., Laval, M., Garcia, C. A., & Reyes-García, V. (2011). Local community attitudes toward forests outside protected areas in India. Impact of legal awareness, trust, and participation. Ecology and Society, 16(3), 10. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-04242-160310

- Manfredo, M. J., Teel, T. L., Don Carlos, A. W., Sullivan, L., Bright, A. D., Dietsch, A. M., Bruskotter, J., & Fulton, D. (2020). The changing sociocultural context of wildlife conservation. Conservation Biology, 34(6), 1549–1559. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13493

- Manohar, M., Lim, E. A. L., Arni, A. G., Badariah, S. J., Fatihah, N. I., Fauzi, M. Z., Libes, J. J., Noordiana, S., Nursayadiq, A., Munieleswar, R., & Puan, C. L. (2012). Review on wildlife value orientation for ecotourism resource management. The Malaysian Forester, 75(1), 1–13.

- Miller, Z. D., Freimund, W., Metcalf, E. C., & Nickerson, N. (2018). Targeting your audience: Wildlife value orientations and the relevance of messages about bear safety. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 23(3), 213–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871209.2017.1409371

- Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation. (1999). Buffer zone management guideline 1999. Government of Nepal, Kathmandu, Nepal.

- Mir, Z. R., Noor, A., Habib, B., & Veeraswami, G. G. (2015). Attitudes of local people toward wildlife conservation: A case study from the Kashmir valley. Mountain Research and Development, 35(4), 392–400. https://doi.org/10.1659/MRD-JOURNAL-D-15-00030.1

- Morais, D. B., KC, B., Mao, Y., & Mosimane, A. (2015). Wildlife conservation through tourism micro-entrepreneurship among Namibian communities. Tourism Review International, 19(1-2), 43–61. https://doi.org/10.3727/154427215X14338796190477

- Morais, D. B., Bunn, D., Hoogendoorn, G., & KC, B. (2018). The potential role of tourism microentrepreneurship in the prevention of rhino poaching. International Development Planning Review, 40(4), 443–461. https://doi.org/10.3828/idpr.2018.21

- Nahuelhual, L., Carmona, A., Lozada, P., Jaramillo, A., & Aguayo, M. (2013). Mapping recreation and ecotourism as a cultural ecosystem service: An application at the local level in southern Chile. Applied Geography, 40, 71–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2012.12.004

- Needham, M. D. (2010). Value orientations toward coral reefs in recreation and tourism settings: A conceptual and measurement approach. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 18(6), 757–772. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669581003690486

- Nepal, S. K., & Weber, K. W. (1995). Managing resources and resolving conflicts: National parks and local people. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, 2(1), 11–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504509.1995.10590662

- Nyaupane, G., & Poudel, S. (2011). Linkages among biodiversity, livelihood, and tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(4), 1344–1366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2011.03.006

- Pant, G., Dhakal, M., Pradhan, N. M. B., Leverington, F., & Hockings, M. (2016). Nature and extent of human–elephant elephas maximus conflict in central Nepal. Oryx, 50(4), 724–731. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605315000381

- Paudyal, R., Thapa, B., Neupane, S. S., & KC, B. (2018). Factors associated with conservation participation by local communities in gaurishankar conservation area project, Nepal. Sustainability, 10(10), 3488. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103488

- Pesonen, J. A., & Tuohino, A. (2017). Activity-based market segmentation of rural well-being tourists: Comparing online information search. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 23(2), 145–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766715610163

- Peterson, M. N., Birckhead, J. L., Leong, K., Peterson, M. J., & Peterson, T. R. (2010). Rearticulating the myth of human–wildlife conflict. Conservation Letters, 3(2), 74–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-263X.2010.00099.x

- Rokeach, M. (1973). The Nature of human values. Free Press.

- Seeland, K. (2000). National Park policy and wildlife problems in Nepal and Bhutan. Population and Environment, 22(1), 43–62. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006629531450

- Serenari, C., Peterson, M. N., Gale, T., & Fahlke, A. (2015). Relationships between value orientations and wildlife conservation policy preferences in Chilean patagonia. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 20(3), 271–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871209.2015.1008113

- Sharma, U. R. (1990). An overview of park-people interactions in Royal Chitwan National Park, Nepal. Landscape and Urban Planning, 19(2), 133–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/0169-2046(90)90049-8

- Shova, T., & Hubacek, K. (2011). Drivers of illegal resource extraction: An analysis of Bardia National Park, Nepal. Journal of Environmental Management, 92(1), 156–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2010.08.021

- Sijtsma, M. T., Vaske, J. J., & Jacobs, M. H. (2012). Acceptability of lethal control of wildlife that damage agriculture in the Netherlands. Society & Natural Resources, 25(12), 1308–1323. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2012.684850

- Snyman, S. (2014). Assessment of the main factors impacting community members’ attitudes towards tourism and protected areas in six southern African countries. Koedoe, 56(2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.4102/koedoe.v56i2.1139

- Snyman, S., & Bricker, K. S. (2019). Living on the edge: Benefit-sharing from protected area tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(6), 705–719. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1615496

- Spiteri, A., & Nepal, S. (2008). Distributing conservation incentives in the buffer zone of Chitwan National Park, Nepal. Environmental Conservation, 35(1), 76–86. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892908004451

- St John, F. A. V., Steadman, J., Austen, G., & Redpath, S. M. (2019). Support for different types of wildlife management is related to underlying human values. People and Nature, 1(1), 6–17.

- Steinhoff, H. W. (1980). Analysis of major conceptual systems for understanding and measuring wildlife values. In W. W. Shaw & E. H. Zube (Eds.), Wildlife values (pp. 11–21). Report 1, Center for Assessment of Noncommodity Natural Resource, University of Arizona, Tucson.

- Stern, P. C., Dietz, T., & Guagnano, G. A. (1995). The new ecological paradigm in social-psychological context. Environment and Behavior, 27(6), 723–743. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916595276001

- Studsrød, J. E., & Wegge, P. (1995). Park-people relationships: The case of damage caused by park animals around the Royal Bardia National Park, Nepal. Environmental Conservation, 22(2), 133–142. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892900010183

- Teel, T. L., & Manfredo, M. J. (2010). Understanding the diversity of public interests in wildlife conservation. Conservation Biology, 24(1), 128–139. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2009.01374.x

- Teel, T. L., Manfredo, M. J., Jensen, F. S., Buijs, A. E., Fischer, A., Riepe, C., Arlinghaus, R., & Jacobs, M. H. (2010). Understanding the cognitive basis for human-wildlife relationships as a key to successful protected-area management. International Journal of Sociology, 40(3), 104–123. https://doi.org/10.2753/IJS0020-7659400306

- Thapa Karki, S. (2013). Do protected areas and conservation incentives contribute to sustainable livelihoods? A case study of Bardia National Park, Nepal. Journal of Environmental Management, 128, 988–999. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2013.06.054

- Thing, S. J., Jones, R., & Jones, C. B. (2017). The politics of conservation: Sonaha, riverscape in the Bardia National Park and buffer zone, Nepal. Conservation and Society, 15(3), 292–303. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26393297

- Umar, B. B., & Kapembwa, J. (2020). Economic benefits, local participation, and conservation ethic in a Game management area: Evidence from Mambwe, Zambia. Tropical Conservation Science, 13, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940082920971754

- Vaske, J. J., Jacobs, M. H., & Sijtsma, M. T. (2011). Wildlife value orientations and demographics in The Netherlands. European Journal of Wildlife Research, 57(6), 1179–1187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10344-011-0531-0

- Walpole, M. J., & Thouless, C. R. (2005). Increasing the value of wildlife through non-consumptive use? Deconstructing the myths of ecotourism and community-based tourism in the tropics. In R. Woodroffe, S. Thirgood, & A. Rabinowitz (Eds.), People and wildlife, conflict or Co-existence? (pp. 122–139). Cambridge University Press.

- Weaver, D. B. (2000). A broad context model of destination development scenarios. Tourism Management, 21(3), 217–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(99)00054-0

- Whittaker, D., Vaske, J. J., & Manfredo, M. J. (2006). Specificity and the cognitive hierarchy: Value orientations and the acceptability of urban wildlife management actions. Society & Natural Resources, 19(6), 515–530. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920600663912

- Wondirad, A. (2019). Does ecotourism contribute to sustainable destination development, or is it just a marketing hoax? Analyzing twenty-five years of contested journey of ecotourism through a meta-analysis of tourism journal publications. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 24(11), 1047–1065. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2019.1665557

- Zainal Abidin, Z. A., & Jacobs, M. H. (2016). The applicability of wildlife value orientations scales to a muslim student sample in Malaysia. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 21(6), 555–566. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871209.2016.1199745

- Zinn, H. C., Manfredo, M. J., & Barro, S. C. (2002). Patterns of wildlife value orientations in hunters’ families. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 7(3), 147–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871200260293324

- Zinn, H. C., & Pierce, C. L. (2002). Values, gender, and concern about potentially dangerous wildlife. Environment and Behavior, 34(2), 239–256. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916502034002005

- Zinn, H. C., & Shen, X. S. (2007). Wildlife value orientations in China. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 12(5), 331–338. doi:10.1080/10871200701555444