ABSTRACT

Today, much of social work is carried out in urban environments, posing distinct challenges to the profession. The complexities of urban life and urban surroundings raise new questions for it, especially in relation to increasing fragmentation, growing inequality, segregation, homelessness, social exclusion, and environmental problems. In general, only little research, however, has been conducted on the performance of social work in urban settings, and urban social work remains conceptually indistinct and not well grounded. Yet, in more recent times, increasing migration to urban settings has prompted more interest in the area. This article presents a two-staged scoping review examining how social work in urban settings is conceptualized in literature from European countries. Our first-stage scoping review findings indicate present conceptualizations of urban social work to be strongly shaped by questions concerning migration, diversity, and new forms of mobility. The second-stage review – leaning on the results of the first phase – concentrated on interrogating closer the knowledge base on urban social work and diversity. The findings suggest that urban social work with migrants is highly related to the question of how to recognize superdiversity in social work bridging relations in urban space, improving access to critical information for migrants, and strengthening social workers’ advocacy for structural change. While urban social work appears to continue to be perceived as problematic, the results highlight the importance of respectful encounters and honest dialogue between migrants and non-migrants and between migrants and professionals, along with the specificity of the use of urban space.

Introduction

As Louis Wirth (Citation1938) already more than 80 years ago noted in his classical essay on the social theory of urban space, global urbanization has brought with it profound changes in virtually every area of social life. In spite of his rather negative view of the consequences of the city, Wirth called for a broader understanding and theorizing of the complicated phenomena of urban life, stressing the benefits of combining ecological, social-organizational, and social psychological standpoints in their study. Indeed, such a broad-based approach was, for him, not just commendable, but also necessitated by the very complexities of urban life and urban surroundings, which posed new challenges to our ability to conceptualize and understand them.

Urban sociology was born out of the Chicago School, which embraced empirical research and its methods, including ethnography (Shlay and Balzarini Citation2015; Addams Citation1990 [1926]). The discipline was also influenced by the work of Simmel (Citation1950 [1905]), who drew attention to personal freedom as an essential element of what he termed the metropolitan individuality, a key characteristic of urban life and urban society. Delanty (Citation2002, Citation2003, 53) has argued, that Chicago School was preoccupied with the idea of a tension between community and society and saw the city through the lens of towns and villages in the rural community, holding a somewhat hostile attitude towards cities due to the impact of industrialism and urban modernization. This myth came to influence the entire enterprise of US American urban sociology. In the European tradition represented by Simmel and Weber (Citation1958 [1905]), the nature of cities was perceived differently, more positively, defining cities where the density offers space for plurality of lifestyles and is a place for self-realization. Under its impact, views on the city became more diverse, more nuanced, and less immediately negative in their overall purport.

This ambivalence of urban sociology remains very much visible still today. Sutton and Kemp (Citation2011, 4), for instance, have argued place to matter for low-income communities of colour because it is simultaneously a source of inequality and oppression and a context of transformation and possibility. City life has also been characterized as relatively unconventional, supporting the notion of duality as it creates various subcultures or sets of interconnected social networks (cf. Fischer Citation1995, 544). Such subcultures range from those connected to ethnic, sexual, and religious minorities to those of the artistic avant-garde and new, innovative groups, but also those associated with criminal and other deviant behaviour. The common denominator in all of them is unconventionality. While Fischer’s research, too, confirms urbanism to be associated with wide range of socio-cultural heterogeneity, what he also shows is that most research on urban subcultures has concentrated on ethnicity.

How, then, does urban social work position itself in relation to urban social theory? Urban surroundings and urban life are also the domain of the discipline of social work, which emerged as a profession and a discipline within the Chicago School of sociology where Jane Addams was a prominent figure. Looking back at the history of social work, Shaw (Citation2011) has highlighted the linkage between the two disciplines, locating it in their effort to find workable solutions to problems within urban communities. Park and Kemp (Citation2006), on the other hand, have underscored the old professional ambiguities in the way environmental and structural forces shaping individuals were understood in each. Elsewhere, Williams (Citation2016) has noted the parallel development of the social work discipline and the city, describing it as a mutual process in which the social work profession has, throughout its history, changed and adapted in tandem with historical developments in urban politics and the changing socio-economic circumstances. Moreover, Williams (Citation2016) claims, that the discipline has been characterized by a dualistic understanding of the urban environment, with the city negatively associated with problems with health and social exclusion or positively associated as new economic opportunities and the possibility to live out diverse social identities.

What makes social work interesting in our time is not only the continuing presence of the ecological perspective, but also the increasingly ‘glocal’ experiences with which it must come to terms (Livholts and Bryant Citation2017; Harrikari and Rauhala Citation2018). Indeed, while much of social work keeps being performed in urban environments, the urban context has, paradoxically and deviating from the discipline’s historical roots, remained somewhat unfamiliar to social work (Delgado Citation2013; Dominelli Citation2012; Williams Citation2016).

The aim of this study is to increase clarity and comprehension on the question of how social work in urban settings is conceptualized in contemporary (2000s’–2010s’) European literature in the field. The method used is a scoping review, based on systematic searches of published peer-reviewed material. This method is particularly appropriate when the field of interest is complex and difficult to grasp and large-scale reviews are not yet available on the topic of interest. While the focus in this article is on the discipline of social work per se, the analysis, where relevant, covers material representing broader social scientific literature as well.

Methods and data

Literature reviews in general may be used to approach a theme either from the perspective of a specific discipline or from a historically broader and more interdisciplinary perspective (Bearfield and Eller Citation2008). Carried out as scoping reviews, they can raise awareness of topics among consumers, practitioners, and even policy makers, as the approach involves aggregating, analysing, and reporting on crucial information in a field (Arksey and O’Malley Citation2005, 6). Following a systematic process, scoping reviews identify articles and studies relevant to key research questions, extract, chart, and synthesize data from them, and, finally, summarize results (Arksey and O’Malley Citation2005; Daudt, van Mossel, and Scott Citation2013; Levac, Colquhoun and Brien Citation2010).

Relatively little, however, has been written about the practical implementation of scoping reviews. The first methodological framework for conducting scoping reviews was presented by Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005). Following their lead, the approach has since then been frequently used in a broad range of fields (Pham et al. Citation2014), to enable one to analytically survey the breadth and range of research activity in them.

The scoping review process in this study was enacted in two stages, and it can be compared to a funnel. First, electronic databases were searched using different search terms within the same field of interest, focusing on grasping a wide and complex field of research. The aim here was to find out how urban social work is conceptualized in research in the field. In the next stage, building on the findings of the first stage, a closer look was taken at what the identified research stated about urban social work with migrants and their communities.

The study was conducted as part of a broader research project on urban social work and migrant integration (Kettunen et al Citation2019). The first author had the main responsibility for conducting the scoping review, while the second and third authors led roundtable discussions with researchers on the different stages of the review. Levac, Colquhoun, and O’Brien (Citation2010) recommends incorporating consultation with stakeholders as a required knowledge translation component of scoping study methodology. In our study the preliminary results of the scoping review were shared and validated in two seminars with stakeholders from professional and migrant communities. The overall process followed the five steps proposed for scoping reviews by Arksey and Malley (Citation2005, 8–9): (1) identification of the research questions; (2) identification of the relevant studies; (3) selections of qualifying studies (4) data charting; and (5) collation, summarizing, and reporting of the final results.

Identification of the research questions

The first step in the review process was to formulate a research question supporting the research aim. The starting point of the research was to explore current understandings of urban social work, which thus far have appeared to be vaguely defined and difficult to grasp. This lack of clarity about them seemed, moreover, to point to a further need: that for more explicit knowledge about what urban social work is. Consequently, the first research question was formulated: How is urban social work conceptualized in existing literature?

The first stage of the process yielded a picture of a fast-growing diversity characterizing the literature on urban social work. A dominant feature in the material was in one way or another related to migrants and the increasing diversity in urban society in terms of its members’ ethnic background, religion, and culture (cf. Bennet Citation2017; Geldof Citation2011). This was discovered to be the case even without at this point having used any specific search terms related to these subjects suggests that social work in urban environments today is closely linked to questions as migration, diversity, and new forms of mobility. Under the conditions of globalization, increased mobility, and on-going climate change, migration is, moreover, only likely to increase in the future, also in its importance as a challenge for social work (100 Resilient Cities Citation2016). Accordingly, this led to the definition of our second research question: What does the literature in the area say about the topic of urban social work and migrant inclusion? This two-staged process, combining a broad research question with a clear articulate scope of inquiry, is also recommended in scoping reviews (Levac, Colquhoun, and O’Brien Citation2010).

Identification of the relevant studies

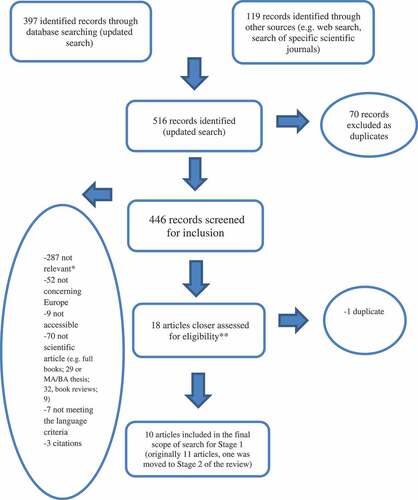

A good search strategy was crucial to ensure that sources in the literature were selected systematically, not merely to prove a point, while still helping to find answers to the research questions asked (Saini and Schlonsky Citation2012). gives an overview of the resulting process.

As the table indicates, the scope of the study had to be limited to a feasible size using pre-selected inclusion and exclusion criteria (cf. Arksey and O’Malley Citation2005, pp. 10–11). The performed scoping review focused on European academic literature to investigate the fast-changing demographics shaping people’s lives in many European cities. This geographic restriction appeared logical, since both the concept of social work and the context and conditions in which it is carried out in practice are largely uniform across the countries of Europe. Early on in the electronic database searches, a decision was made to also include a new academic journal, Urban Social Work, published since 2017 in the United States, as excluding a publication specifically devoted to the theme might have led to missing valuable current information on the topic. Noteworthy here is also how the fact of the existence of a newly founded specialist journal focusing solely on urban social work only highlights the topicality of our research topic more.

The languages included in the search were English, Finnish, and Swedish; for the hand search also Norwegian was included. Other languages were excluded due to the researchers’ lack of familiarity with them as well as the cost of translating the data (along with the time required for it). As further delimitations (not indicated in ), the subject areas of business and economics were not included in the ProQuest database platform search. As for the time frame, only work published from 2000 onwards was included. On the part of articles, only peer-reviewed work was searched (where possible) in order to secure that only high quality publications were included. No decision, on the other hand, was made to only include full-text articles, as that would have meant increased risk of excluding significant material (cf. Aveyard Citation2014). As for the inclusion criteria, the article’s abstract or title had to make a specific reference to some type of social work in cities or urban areas in order for it to be selected. The sources did not, however, need to contain the exact terms ‘social work’ and ‘urban area’, as social work is pursued in Europe using a variety of labels. Yet, these two topics needed to be addressed in one way or another.

The hand search entailed manually searching relevant key journals to identify potentially relevant studies that might have been missed in the electronic searches, given that titles and abstracts are often insufficient in themselves to properly disclose the subject area (cf. Saini and Schlonsky Citation2012). The hand searches during the first stage covered the journals Nordic Social Work Research, Nordisk sosialt arbeid, and Urban Social Work, as well as the University of Helsinki Library, E-thesis (web storage service for University of Helsinki theses and dissertations), and the library of the Norwegian University of Science and Technology. The Nordic university libraries and academic journals were added to the search later as the database searches did not return a sufficient number of articles on urban social work within the Nordic context. At this time, also a Google search was performed without any date restrictions, yielding a total of 51 records.

The searches for the scoping review were conducted over a six-month period in late 2017–summer 2018, when a final review of the search process was performed to finalize the flow chart of the search process. The overall search was conducted and reviewed systematically several times to grasp the content and identify the best ways to utilize the search tools within the different databases. The most popular electronic databases for social work research literature were searched, including EBSCOhost, Applied Social Sciences Index & Abstract (ProQuest), Sociological Abstracts (ProQuest), Social Sciences Citation Index (Web of Science), Scopus (Elsevier), and Google Scholar. The search terms used at this stage were ‘urban social work’, ‘urbant socialt arbete’ (Swedish), and ‘kaupunkisosiaalityö’ (Finnish), while the search combinations were ‘social work AND city OR urban. The decision to include or exclude found articles was made by first reading their headlines and then their abstracts. This was a challenging process and we found it helpful that the selection of studies was discussed within the research project team. This helped to alleviate the ambiguity with the initial broad research question and ensured that abstracts selected were relevant (cf. Levac, Colquhoun, and O’Brien Citation2010). Clearly irrelevant sources were excluded, most often for the reason that they did not refer to social work in urban areas. describes the database searches more in detail.

To obtain as wide a range of data as possible during the first stage of the review, also other search terms were tested with the databases, such as ‘community work [or “community social work”] AND city’, ‘community work AND urban area’. shows the flow of articles through this second stage of identifying the data during the first stage of the review process, from the identification of relevant data to their final inclusion in the scoping review. The results of the database searches here were narrowed to ten articles selected based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria given in the flow chart.

The original searches yielded a total of 1,811 potentially relevant sources. Subsequent to it, the revised search returned 516 results, including 397 from the electronic database search and 119 from the hand search of specific journals and library databases. At this point, 70 duplicates were excluded. The 446 remaining articles were then screened by title and abstract, leading to the exclusion of a number of items. As shown on the right side of , the majority of the articles excluded at this stage were omitted due to lack of relevance, as they did not address social work. Following a closer examination of the data in 18 articles to verify their eligibility, 17 articles remained. Ten of these were included in the final scoping review, with one article later moved to Stage Two of the review as it was more relevant to the second research question. The reference management software RefWorks was used to collect, transmit, and chart the data.

Selection of qualifying studies

In the following stage, the final selection of sources to be included in the review was performed. At this stage the research question addressed directed the final selection of articles. This phase could only be checked by critically examining the full texts, as abstracts do not always present the content of articles fully or properly. The research team jointly discussed the article selections, refined the search strategy, identified inconsistencies in relation to the criteria and the addressed research questions and made also suggestions for hand search. The results of the selection process are shown in .

Data Charting

Once the selection of the articles had been completed, data charting could commence. The data charting here involved listing all the chosen data in a table format to distinguish different aspects such as the author(s), publication year, study location, study aims, and methodology. The data collected in Stage One consisted of a total of 10 articles published in 2000–2017 in the peer-reviewed English-language journals European Journal of Social Work (n = 5), Urban Social Work (n = 2), Environment and Planning A (n = 1), and Policy and Politics (n = 1), and in the Nordisk Sosialt Arbeid (n = 1). Eight of the articles were published in 2010 or later, while two were published before 2005. Eight concerned urban social work in European contexts and two in the United States.

Of these total of ten articles identified in Stage One, eight examined social work research and practice in urban contexts in either Belgium (n = 2), the Netherlands (n = 2), the United States (n = 2), Germany (n = 1), or Finland (n = 1). One article was on research projects and practices in several countries, while one reported on a comparative research project involving cities in Finland, Germany, and the United Kingdom, and one discussed research on urban social work in Europe in general, not in any particular city. Some of the articles were literature reviews conducted in a variety of ways. One was a pure review article (Geldof Citation2011), while others presented more narrow, selective literature reviews as a supplement to other methods used, such as ethnographical observation and interviews. All the articles included were qualitative in nature, although that was not an inclusion criterion in this study.

Results

The research process followed the structure of the scoping review. We used the recommendations of Levac, Colquhoun, and O’Brien (Citation2010) and processed with descriptive analytical method that involves summarizing process information, and continued with thematic analysis to make sense of the extracted data. The first stage involved searching for different characterizations of urban social work. Due to the heavy concentration on migration issues in the first stage findings, the second stage focused more closely on social work with migrant inclusion processes in urban settings. The study selection was limited by clear directives set for the focus (Schreier Citation2012). To detect different themes relevant to both of the two research questions in this study, a data-driven thematic analysis informed by the literature on urban sociology was performed (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). The material was closely analysed and segmented into units matching the coding frames. The terms ‘urban’, ‘city’, ‘social work’, and ‘community work’ were deconstructed to understand how they were categorized and classified. Based on this analysis, four main themes emerged.

Stage one: four central features shaping urban social work

The articles found in Stage One of the review frequently discussed or highlighted the following four themes as emergent features shaping social work in urban areas: fast-accelerating diversity impacting upon people’s lives in large urban areas, interculturalization of social work, working in complex social networks, and a new community approach.

Fast-accelerating diversity

In the articles in this review, urban areas were described as fast-changing environments in which density is both an emerging and a fundamental element shaping people’s lives (Geldof Citation2011). Indeed, many European cities are becoming superdiverse, with urban transformation gradually normalizing diversity. The main target groups in the articles were in one way or another linked to migrants and the growth of populations with increasingly diverse ethnic, religious, and cultural backgrounds (Bennett, Citation2017; Geldof Citation2011). All this became apparent in the first stage of the search process with no search terms specifically related to migration used, suggesting social work in today’s urban environments to be strongly related to questions concerning migration, diversity, and new forms of mobility. Another characteristic of urban social work revealed in the data was that it often appeared fraught with tensions, owing partly to national social protection systems and legal systems not yet having adapted their methods to accommodate the changes in society (Geldof Citation2011; Geldof, Schrooten, and Withaeckx Citation2017).

Gentrification was presented as a key challenge to urban social work as deprives neighbourhoods can enclose people in their deprivation and reinforce social exclusion of inhabitants. Indeed, it can be seen as one of the downsides of failed urban renewal projects, leading to rent increases forcing some residents out of their homes. It was seen too often to affect particularly people or groups that already find themselves in a difficult a socio-economic situation, such as ageing people, ethnic minorities, and those at risk of marginalization for other reasons (Birk Citation2016; Crewe Citation2017).

Interculturalization of social work

Another central theme in the literature was interculturalization, bringing new challenges to urban social work from fast-growing diversity. At the same time, urban social work seems to still lack tools suited for the diversity of its today’s urban clientele. As Shaw (Citation2011) put it, there is a need to add ‘urbanness’ to the social work practice. Until now, the profession has continued to be circumscribed by the highly normative frames of the welfare state. Insufficient knowledge of the cultural background, their life history and present living conditions of ethnic minorities give rise to a certain tension between, on the one hand, those creating the frames and setting the norms (often native-born residents) and, on the other hand, those not represented in the norm (migrants) (Hendriks and van Ewijk Citation2019). As stressed by Birk (Citation2016) urban social work is not neutral, as it, too, carries within itself the norms and hierarchies of the welfare state – a fact that urban community work practice often neglects to consider. Prompted by phenomena like transmigration and changing migration patterns, national integration courses and programmes are launched, but they often lack tools to take into account the inherent temporality of the target group, with services designed for migrants expected to stay permanently, not for short duration only. Transmigration negatively affects transmigrants’ ability to build social capital and meet their welfare needs, which both are crucial to urban social work success (Geldof Citation2011; Geldof, Schrooten and Withaeckx 201; Roivainen Citation2004). There is, thus, an urgent need to interculturalize not only the way social work operates today but also to develop the curricula for social work and research methodology to engage and take into account the views of ethnic groups that are not reached or involved (Geldoff Citation2011).

Complex social networks

With the increasingly diverse needs of urban clients coming from different cultures, histories, classes, and ethnicities, also the need for more diversified knowledge was seen as becoming only more and more pressing. Social workers operate in complex networks in which many actors and institutions collaborate. Clients are offered a range of alternative social services, but these may be scattered and fragmented (Geldof Citation2011; Roivainen Citation2004). Urban networks of people, moreover, keep constantly changing, and they steadily grow more diverse and transnational (Geldof, Schrooten, and Withaeckx Citation2017). While social networks are thus central to urban social work, they have not yet been sufficiently recognized as such by the profession. Many of the articles in this study stressed the variety of social problems in dense cities, describing them as a product of deprived and marginalized neighbourhoods where weak social networks often lead to alienation and polarization. Thus, gentrification was identified as a threat to urban social networks (Crewe Citation2017; Geldof Citation2011; Roivainen Citation2004).

According to Hendriks and van Ewijk (Citation2019), urban social work should be perceived as a process rather than a solid, clear demarcation of the tasks of different professionals. At best, professional collaboration beyond professional boundaries and working in networks can lead to a broader insight into the reality of people’s lives in an urban environment and finding functional solutions (Geldof Citation2011). Birk (Citation2016) proposes the concept of ‘infrastructuring the social’ to describe the way urban networks in which professionals, residents, policies, and temporal immaterialities of everyday life are entangled operate. Referring to ‘people as infrastructures’, he proposes people to be able to accomplish the infrastructuring of residential areas in cities, albeit in interaction with state policies and the economy. This form of social infrastructuring, for him, is built upon relationships between people, institutions, and spaces, as well as resources and norms.

New forms of community work

For Roivainen (Citation2004), the changing urban environment requires viewing urban communities afresh from the perspective of community social work. In Shaw (Citation2011), the strong link between individuals’ well-being and their relationships to their communities is stressed, as a criticism of the one-sided focus of social work on cases and individuals. Also Matthies et al (Citation2004, p. 43) and Crewe (Citation2017, pp. 56–57) draw attention to the importance of engaging with one’s living environment, which, they note, promotes individual social and economic development and preventing social exclusion. Moreover, as Bennett, (Citation2017) points out, community and living location play more significant roles in social outcomes than individual characteristics. Gentrification was given as a concrete example of how urban neighbourhoods are changing and where expertise at the local level is needed (Birk Citation2016; Crewe Citation2017). These types of environmental developments were seen as calling for a new form of relational community social work approach closer to the individual in a given situation.

To summarize, despite its historically European, relatively positive sociological views of the city, the academic research included in this review often revealed a fairly problem-oriented understanding of urban social work. Concepts such as a disadvantaged, marginalized, and troubled neighbourhood were frequently put forth in discussions on urban social work. There also appeared to be a rather negative discourse that labelled urban places as mainly problematic and in need of intervention. Such views were however, deemed as potentially harmful to social work, since its target groups rarely have an equal say in public and scholarly discussions (Birk Citation2016; Krumer-Nevo and Sidi Citation2012).

Stage two: social work with migrants in urban settings

The second research question required specifically scrutinizing knowledge on urban social work and migrant inclusion. The second database search and the narrower research question in the scoping review yielded seven articles on urban social work with migrants in European contexts. Of these, four specifically examined urban social work with migrants. Of the remaining three, one looked at communication between home and school personnel, including interviews with social workers in the Helsinki metropolitan area (Säävälä, Turjanmaa and Alitolppa-Niitamo Citation2015). Another one reviewed integration work with migrants in Finnish urban areas including social workers (Vuori Citation2015). The third one studied the way parents with children in child service centres perceived social support and social cohesion in diverse urban contexts (Geens, Roets, and Vandenbroeck Citation2017). Three of the articles investigated these topics from their target group’s point of view, while the other four focused on professionals’ and development perspectives. presents the general characteristics in stage two, including study location, type of study and target group.

Four themes emerged: (1) recognizing superdiversity in social work; (2) bridging relations in urban spaces; (3) improving communication channels to access critical information; and (4) advocating for structural change.

Recognizing superdiversity

Social workers in large cities today encounter exponentially more clients from multinational, multilingual, and multicultural contexts than in the past, which puts their ability to work with diverse clientele to the test (Genova and Barberis Citation2019). Judging from our data, social workers seem to have three main approaches to tackling this urban challenge: (1) collaboration with external interculturally aware social workers (Genova and Barberis Citation2019); (2) internalization and normalization of (super)diversity in the practice of all urban social workers; and (3) a combination of these two. Collaboration with external mediators was described by Genova and Barberis (Citation2019), who studied intercultural mediation as a practical response to solving challenges faced by urban social workers in Italy. An intercultural mediator, for the authors, is a go-between professional who has professional skills such as cultural, linguistic, juridical, social work, conflict management, and empowerment competences. Mediators describe themselves as facilitators of relationships and as bridges between civil servants, social workers, and other professionals. Genova and Barberis (Citation2019) estimate in their article, that interpersonal collaboration can be helpful, but it cannot offer any definite solution without organizations that apply anti-discriminatory and collaborative practices in social welfare institutions. What Genova and Barberis and also Geldoff point out is that ethnicity awareness is not just a question of techniques but about perspectives and integrative models applied that address structural inequalities in society with the aim to empower users by reducing the negative effects of hierarchy in their immediate interaction and the work they do together (cf. Dominelli Citation1998: 7; Mullaly Citation2010). Similarly, also for Vuori (Citation2015) integration work cannot be performed without stepping outside the office and collaborating more broader within the community; in addition, there is an urgent need for a two-sided approach to inclusion that facilitates genuine dialogue between social workers and migrants.

Congress (Citation2017) presents a new approach to these challenges: cultural humility. In it social workers seek to reciprocally learn from clients about their culture, values, and thoughts. This approach eschews practices based on preconceived perceptions of different cultures. Indeed, Congress suggests, it represents a way of normalizing diversity. This approach comes close to the notion of superdiversity put forth by others (Geldof Citation2011; Vertovec Citation2007). To facilitate its micro-scale implementation in practice, Congress presents a family assessment tool, designed to promote a humbler orientation among urban social workers. This tool serves as a platform for discussion on various factors such as legal status, values, education, work, family structure, power, myths, rules, and reasons for and time of migration, along with themes such as oppression, discrimination, bias, and racism.

Bridging relations in urban space

Cities entail a multitude of encounters with a great variety of content that can either facilitate migrant inclusion or obstruct it. The articles in this review discussed several urban places, primarily child care service centres, schools, housing estates, neighbourhoods, open urban spaces (e.g., parks, streets, and malls), and places more directly involved in formal integration services, such as social welfare offices and agencies providing services to facilitate migrant inclusion (e.g., Franz Citation2012). Geens, Roets, and Vandenbroeck (Citation2017) studied the everyday encounters in childcare services of parents having migrated to urban areas in Belgium, comparing these to those of non-migrant parents. A central finding in the study was that migrants were left alone in the urban environment, leading the authors to suggest that it is vital for urban social work professionals to stimulate informal encounters between migrant and non-migrant residents. Such bridging relations were described as light, ephemeral contacts that may lead to social connectedness and social leverage. They allow becoming familiar with diversity while decoding the other and finding one’s place in the ‘multi-ness’ of the city.

Improving access to critical information

For migrants, the operation of societal structures in the arrival country can be confusing, especially if the context is a complex urban one. The reviewed articles stressed the need to improve communication channels and information flows. Geldof, Schrooten, and Withaeckx (Citation2017) found the transmigrants participating in their study to lack information about their social rights; the same applied to access to available social services in the city. In Geens, Roets, and Vandenbroeck (Citation2017), migrant parents stressed their desire to become more acquainted with locals, which they believed would help them learn how the systems in the receiving society worked. Many of the parents in Säävälä, Turjanmaa, and Alitoppa-Niitamo. (Citation2015), for their part, reported themselves to find schools inaccessible and lack information about their children’s education and well-being. A similar situation could be observed in the United States, where Congress (Citation2017) found many migrants to not know how to take full advantage of the social and health care services to which they are entitled.

Advocating for structural change

Many articles in the second stage of this review confirmed the urgent need for structural changes in urban social work in order to facilitate migrant inclusion. According to Genova and Barberis (Citation2019), for instance, change demands structural innovations, implementation of anti-discriminatory practices, and broader collaboration within social welfare institutions. On a macro level, Congress (Citation2017) highlights advocacy efforts to change societal views on migrant policies, including advocacy campaigns and campaigns to increase awareness of the importance of educating all social workers and students about current threats to the ethical codes of social work. Also Vuori (Citation2015) promotes similar advocacy approaches, while also noting that these are not customary in the field of migrant inclusion in Finland. Micro-level change requires many macro-level encounters and innovations, which can be achieved, for instance, by assessing how encounters succeed, identifying inadequate language skills, and making services safer and more accessible for everyone (Congress Citation2017; Vuori Citation2015).

Discussion

This scoping review approached contemporary urban social work from two perspectives. First, it examined current conceptualizations and characterizations of urban social work; second, it examined the knowledge base of urban social work carried out in the context of ethnic diversity. Despite the relatively small final sample size (n = 17), our findings support the understanding that individuals are linked to their physical space and, more specifically, factors in the urban surroundings that influence and make social work more specific. This time–space compression sets boundary conditions for social work, which needs to be better understood and researched. The articles included in the review discussed social work in urban spaces, speaking of its challenges and tensions and ways to build a new knowledge base on urban social work.

Emerging concepts

Looking more closely at the contemporary understandings of urban social work in the reviewed material, we find concepts such as superdiversity, transmigration, gentrification, interculturalization of social work, and complex social and transnational networks. All of them describe the way urban social work is understood today, being one way or another linked to increasing urban diversity. Overall, the material from the first stage of the scoping review seems to place a strong emphasis on migrants and diversity.

Addressing unconventionality

In our sample, there were studies showing European cities with a longer experience of migration to often lack the expertise to effectively address their residents’ changing needs, while places with shorter migration histories appeared to often lack general expertise in policy attention (e.g., Genova and Barberis Citation2019). The urban developments in the 2000s have, broadly speaking, been marked by tensions arising from this condition. Despite the influence on it of the European sociological tradition with its originally more versatile, even positive view of the city, the findings from this scoping review show research on urban social work to often be conducted in a problem-centred manner. Concepts such as disadvantaged, marginalized, and troubled neighbourhoods were frequently employed. This negatively tinged discourse tended to label urban places as problematic and in need of intervention. Some studies, however, constructively approached the use of urban space and the specificity of encounters as having vital implications for urban social work (Birk Citation2016; Congress Citation2017; Geens, Roets, and Vandenbroeck Citation2017; Säävälä, Turjanmaa, and Alitoppa-Niitamo. Citation2015).

Understandings of urban social work and migrant inclusion

A prominent theme in Fischer’s (Citation1975) subcultural theory is unconventionality. How does unconventionality manifest itself in today’s urban social work contexts? How is social work understood and enacted vis-à-vis the new complexity marking its modern urban context? In this scoping review, different ways to approach this challenge could be identified.

On the one hand, specific methods and solutions are explored in the literature, for instance by interculturally aware social workers, while, on the other hand, more general approaches are advocated (e.g., interculturalization, cultural humility, superdiversity). Diversity shapes social work, as Williams (Citation2016) has put it. With superdiversity becoming more the norm than the exception in large cities, dealing with complexity and unconventionality calls for taking this capacity into use and finding more proactive, community based and collaborate solutions. Dealing with complexity also entails advocating structural changes, both on an individual level and societal level, to enable a more sustainable urban social work practice.

Conclusions

In this scoping review, we looked to identify studies addressing themselves to the nexus between social work and urban settings. The material in it consisted primarily of qualitative studies, but also case studies and examples of mixed-methods research. Scoping studies may be particularly relevant to disciplines with emerging evidence, such as social work and as researchers we found this method ideal due to its inclusion of a broad range of study designs and addressing questions beyond those related to intervention effectiveness. We found the recommendations of successful completion of scoping studies (Levac, Colquhoun, and O’Brien Citation2010) helpful. This concerns particularly involving a broader research team consisting of researchers with content and methodological expertise in the different phases of the scoping study and using consultation with professional and migrant community members to verify the preliminary results, even though the consultation would have needed a clearer articulation of how the data could be integrated within the overall study outcome.

One of the core elements of urban social work is ‘the city’. In Wirth (Citation1938), one central dimension of city life was overlooked: freedom, in the positive sense of Simmel. The city is a place for free self-realization and therefore attracts all kinds of people. The unconventionality marking it is, moreover, continuously renewed, as that which has previously been atypical becomes normalized in society and new unconventional categories are created. This is the innovation and potential that tends to remain unrecognized in social work when the focus is for the most part laid on negative effects alone.

The core of urban social work consists of encounters and interpersonal communication. Dialogue and facilitation play a central role in the early phases of inclusion processes, providing the way to further inclusion. Sennett (Citation2012) has elaborated on the issue of encountering diversity with useful anecdotes, one of which is of Jane Addams working in settlement houses. In Chicago, Jane Addams was struck by the fact that although immigrants felt comfortable with associating with people they knew (people like them) – which, on the other hand, locked them into marginality – even then they did not bond strongly. The social question in the settlement houses thus became two-fold: how to encourage co-operation with others who were different, and how to stimulate the desire to associate at all. Addams responded to the problems of difference and encounters in a stunningly simple way: she focused on everyday experience – parenting, schooling, shopping. Accordingly, her Hull House came to emphasize loose rather than rigid exchanges and made a virtue out of informality (Sennett Citation2012, pp. 51–52). Cities are an important place of departure for contemporary social work, creating creative spaces for action, incorporating the knowledge of local inhabitants in social change work, and allowing bottom-up approaches to new challenges. In urban social work, communities organizing around welfare/social challenges are understood as part of a critical social work practice (Williams Citation2016). This form of broad community based approach, already endorsed by Wirth (Citation1938), is relevant and necessitated by today’s fast-accelerated demographic changes. Honest and open dialogue, genuine interest, and respectful encounters when facing diversity and unconventionality may result in reciprocal learning in also our own contemporary urban working contexts. Urban social work within a broader diversity context includes ethnicity, that is intertwined with class, race, gender and heteronormativity. This broader diversity should promote innovative practice and method development including both formal and informal strategies. Urban social work research and practice needs to start from people’s social realities to find empowering tools for social work. As demonstrated in the studies there appears to be an urgent need to diversify services and social work that have long relied on monocultural models of service provision and care.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- 100 Resilient Cities. 2016. Global Migration: Resilient Cities at the Forefront: Strategic Actions to Adapt and Transform Our Cities in an Age of Migration 100 Resilient Cities. h t t p://1 0 0resilientcities.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Report-Global-Migration.pdf

- Addams, J. 1990 [1926]. Twenty Years at Hull House with Biographical Notes. New York: Macmillan.

- Arksey, H., and L. O’Malley. 2005. “Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8 (1): 19–32. doi:10.1080/1364557032000119616.

- Aveyard, H. 2014. Doing A Literature Review in the Health and Social Care: A Practical Guide. 3rd ed. Berkshire: Open University Press.

- Bearfield, D., and W. Eller. 2008. “Writing a Literature Review: The Art of Scientific Literature.” In Handbook of Research Methods in Public Administration, edited by K. Yang and G. J. Miller, 61–72. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

- Bennett, M. D. 2017. “Neighborhood Disorder, Urban Stressors, and Street Codes: A Model for Exploring Social Determinants of Life-course Trajectories.” Urban Social Work 1 (2): 89–103. doi:10.1891/2474-8684.1.2.89.

- Birk, R. 2016. “Infrastructuring the Social: Local Community Work, Urban Policy and Marginalized Residential Areas in Denmark.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 49 (4): 767–783. doi:10.1177/0308518X16683187.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Congress, E. 2017. “Immigrants and Refugees in Cities: Issues, Challenges, and Interventions for Social Workers.” Urban Social Work 1 (1): 20–34. doi:10.1891/2474-8684.1.1.20.

- Crewe, S. E. 2017. “Aging and Gentrification: The Urban Experience.” Urban Social Work 1 (1): 53–64. doi:10.1891/2474-8684.1.1.53.

- Daudt, H. M. L., C. van Mossel, and S. J. Scott. 2013. “Enhancing the Scoping Study Methodology: A Large, Inter-Professional Team’s Experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s Framework.” BMC Medical Research Methodology 13 (article): 48. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-13-48.

- Delanty, G. 2002. “Communitaranism and Citizenship.” In Handbook of Citizenship Studies, edited by E. F. Isin and B. S. Turner, 159–174. London, Thousands Oak, New Delhi: Sage.

- Delanty, G. 2003. Community. London: Routledge.

- Delgado, M. 2013. Social Justice and the Urban Obesity Crisis: Implications for Social Work. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Dominelli, L. 1998. “Anti-Oppressive Practice in Context.” In Social Work, Themes, Issues and Critical Debates, edited by R. Adams, L. Dominelli, and M. Payne, 3–17. London: Macmillan.

- Dominelli, L. 2012. Green Social Work: From Environmental Crises to Environmental Justice. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Evers, A., A. D. Schulz, and C. Wiesner. 2006. “Local Policy Networks in the Programme Social City – A Case in Point for New Forms of Governance in the Field of Local Social Work and Urban Planning.” European Journal of Social Work 9 (2): 183–200. doi:10.1080/13691450600723039.

- Fischer, C. 1975. “Toward a Subcultural Theory of Urbanism.” American Journal of Sociology 80 (6): 1319–1341. doi:10.1086/225993.

- Fischer, C. 1995. “Subcultural Theory of Urbanism: A Twentieth-Year Assessment.” American Journal of Sociology 101 (3): 543–577. doi:10.1086/230753.

- Franz, B. 2012. “Immigrant Youth, Hip-hop, and Feminist Pedagogy: Outlines of an Alternative Integration Policy in Vienna, Austria.” International Studies Perspectives 13 (3): 270–288. doi:10.1111/j.1528-3585.2012.00484.x.

- Geens, N., G. Roets, and M. Vandenbroeck. 2017. “Parents’ Perspectives of Social Support and Social Cohesion in Urban Context of Diversity.” European Journal of Social Work 22 (3): 423–434. doi:10.1080/13691457.2017.1366426.

- Geldof, D. 2011. “New Challenges for Urban Social Work and Urban Social Work Research.” European Journal of Social Work 14 (1): 27–39. doi:10.1080/13691457.2010.516621.

- Geldof, D., M. Schrooten, and S. Withaeckx. 2017. “Transmigration: The Rise of Flexible Migration Strategies as Part of Superdiversity.” Policy and Politics 45 (4): 567–584. doi:10.1332/030557317X14972774011385.

- Genova, A., and E. Barberis. 2019. “Social Workers and Intercultural Mediators: Challenges for Collaboration and Intercultural Awareness.” European Journal of Social Work 22 (6): 908–920. doi:10.1080/13691457.2018.1452196.

- Harrikari, T., and P.-L. Rauhala. 2018. Towards Glocal Social Work in the Era of Compressed Modernity. London: Routledge.

- Hendriks, P., and E. Hans van. 2019. “Finding Common Ground: How Superdiversity Is Unsettling Social Work Education.” European Journal of Social Work 22 (1): 158–170. doi:10.1080/13691457.2017.1366431.

- Kettunen, Aija, Marianne Nylund, Aino-Elina Pesonen, Ilse Julkunen, Erja Saurama, Maria Tapola-Haapala, Heino, Päivi, Anna Nurmi, and Karolina Asén. 2019. Kotoutuminen on muutakin kuin koulutusta ja työtä. Dialogi. https://dialogi.diak.fi/2019/03/21/kotoutuminen-on-muutakin-kuin-koulutusta-ja-tyota/

- Krumer-Nevo, M., and M. Sidi. 2012. “Writing against Othering.” Qualitative Inquiry 18 (4): 299–309. doi:10.1177/1077800411433546.

- Levac, D., H. Colquhoun, and K. O’Brien. 2010. “Scoping Studies: Advancing the Methodology.” Implementation Science 5 (article): 69. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-5-69.

- Livholts, M., and L. Bryant, eds. 2017. Social Work in a Glocalised World. London: Routledge.

- Matthies, A.-L., P. Turunen, S. Albers, T. Boeck, and N. Kati. 2004. “An Eco-Social Approach to Tackling Social Exclusion in European Cities: A New Comparative Research Project in Progress.” European Journal of Social Work 3 (1): 43–52. doi:10.1080/714052811.

- Moretti, C. 2017. “Social Housing Mediation: Education Path for Social Workers.” European Journal of Social Work 20 (3): 429–440. doi:10.1080/13691457.2017.1314934.

- Mullaly, B. 2010. Challenging Oppression and Confronting Privilege. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Park, Y., and S. P. Kemp. 2006. ““Little Alien Colonies”: Representations of Immigrants and Their Neighborhoods in Social Work Discourse, 1875–1924.” Social Service Review 80 (4): 705–734. doi:10.1086/507934.

- Pham, M. T., J. D. Adrijana Rajić, J. M. Greig, A. P. Sargeant, S. A. McEwen, and S. A. McEwen. 2014. “A Scoping Review of Scoping Reviews: Advancing the Approach and Enhancing the Consistency.” Research Synthesis Methods 5 (4): 371–385. doi:10.1002/jrsm.1123.

- Roivainen, I. 2004. “Local Communities as a Field of Community Social Work: Nordic Community Work from the Perspective of Finnish Community-Based Social Work.” Nordisk Sosialt Arbeid 3 (24): 194–206.

- Säävälä, M., E. Turjanmaa, and A. Alitoppa-Niitamo. 2015. “Immigrant Home–School Information Flows in Finnish Comprehensive Schools.” International Journal of Migration, Health and Social Care 13 (1): 39–52. doi:10.1108/IJMHSC-10-2015-0040.

- Saini, M., and A. Schlonsky. 2012. Systematic Synthesis of Qualitative Research. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Schreier, M. 2012. Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Sennett, R. 2012. Together: The Rituals, Pleasures and Politics of Cooperation. London: Penguin Books.

- Shaw, I. 2011. “Social Work Research – An Urban Desert?” European Journal of Social Work 14 (1): 11–26. doi:10.1080/13691457.2010.516615.

- Shlay, A. B., and J. Balzarini. 2015. “Urban Sociology.” In In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, edited by J. D. Wright, 926–933. 2nd ed. Oxford: Elsevier.

- Simmel, G. 1950. “[1905]. The Metropolis and Mental Life.” In The Sociology of Georg Simmel, edited by K. H. Wolff, and trans. 409–424. New York: Free Press.

- Sutton, S. E., and S. P. Kemp. 2011. The Paradox of Urban Space: Inequality and Transformation in Marginalized Communities. New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Vertovec, S. 2007. “Super-Diversity and Its Implications.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 30 (6): 1024–1054. doi:10.1080/01419870701599465.

- Vuori, J. 2015. “Kotouttaminen Arjen Kansalaisuuden Rakentamisena.” Yhteiskuntapolitiikka 80 (4): 395–404.

- Weber, M. 1958 [1905]. The City. New York: Free Press.

- Williams, C. 2016. Social Work and the City: Urban Themes in 21th-Century Social Work. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Wirth, L. 1938. “Urbanism as a Way of Life.” The American Journal of Sociology 44 (1): 1–24. doi:10.1086/217913.

Appendix

Table 1. Database searches: Search types and variables, with data sources included and excluded.

Table 2. Search databases, search features, and records identified.

Table 3. General characteristics of articles included in Stage One.

Table 4. General characteristics of articles included in Stage Two.