ABSTRACT

Various digital platforms are currently being introduced in many fields, including social work. This research presents the Digital Activity Plan (DAP) introduced by the Norwegian welfare and labour administration (Nav) in 2017 as a case to investigate how governmental digital platforms impact social work practices. DAP has several intentions for developing digital client communication and managing casework for counsellors, as well as governing and implementing social policies. This article aims to investigate the socio-technical affordances of the digital platform and how it affects the role of the counsellors in Nav. The article defines five affordances of DAP: client communication, information systems, citizen-state contract, measuring, and political instruments. It discusses these affordances from both the counsellor’s experiences and in light of contemporary social politics and research. The results from this case show the impact of digital platforms on social work, how multifaceted socio-technical assemblages emerge, and how complex negotiations of platform affordances take place.

Introduction

We are in the midst of a digital transformation leading to new challenges and opportunities for the social work profession. The development of digital tools for social work has progressed rapidly, and the need for scrutinizing how it impacts the profession is called for by numerous researchers within the field (Garrett Citation2005; Devlieghere, Roose, and Evans Citation2020). This paper presents a case study on the use and impact of a digital platform in social work practices. This article aims to advance our understanding of the characteristics and form of the profession when challenged by digital transformation. Information systems are not new to social work organizations; however, what separates platforms from previous digital technologies is that the system includes clients. The platform becomes an arena for practicing social work.

The Norwegian government’s digitalization strategy was released in spring 2019 and presented an ambitious plan for digitalizing the entire public sector (Ministry of Local Government and Modernization Citation2019). Organizational changes led by digitalization policies might impact the terms for both social work professionals and their clients, sometimes in unpredictable ways and not always as envisioned. Research on Digital Activity Plan (DAP) as one of the new platforms sheds light on the impact of digital platforms in social work. In what ways do counsellors’Footnote1 roles and practices change due to the introduction of DAP? What new challenges and possibilities lie within the platform, and how are these affordances negotiated and shaped in social work practice? These are the main questions that will be discussed in the article.

Previous research

The digital transformation and development of digital services for social work is not a unique situation for Norway or Nav. There is an increased use of digital tools in social work across Europe and the US (Aguilar-Idañez, Caparrós-Civera, and Anaut-Bravo Citation2018; Mihai et al. Citation2016; Eubanks Citation2018). The research literature on digital technology covers a wide range of topics on concerns and possibilities related to diverse digital technology solutions. The previous research relevant to this study concerns information systems and digital communication as the platform in this study includes both.

The use of information systems has long traditions in social work (Hill and Shaw Citation2011). Research on how information systems impact social work is diverse as the social work it revolves around is complex and varied. Several researchers argue that social workers need to take part in developing the information systems to make them suitable for their practices (Lagsten and Andersson Citation2018; Mackrill and Ebsen Citation2018). Systems that poorly fit the routines and professionals’ work practices can lead them to having to do ‘workarounds’ to adjust the system to their professional needs (Røhnebæk Citation2014). Gillingham (Citation2018) points out that information systems in social work can be alleged technological fixes for complex organizational problems in social work agencies. Both aspects show how digital technologies are complexly negotiated in the field by multiple actors.

Digital communication in social work is a research field that has expanded as interacting digitally has evolved to be a new norm in society. Examples stretch across various areas of social work and involve different types of interaction, ranging from multi-sided open communication through social media (Chan Citation2016) to virtual support groups (Miller et al. Citation2019) and anonymous online counselling services (Nesmith Citation2018). The transfer to digital communication platforms can serve as a substitute or supplement to traditional offline services, such as when geographic distances make it difficult to offer traditional services (Bryant et al. Citation2018). Best and colleagues (Citation2014) found that the mental well-being of adolescent males improved by being able to communicate online about feelings. Best encourages social work practitioners to recognize this shift in help-seeking in terms of providing and commissioning interpersonal helping via digital platforms. Other researchers problematize the shift towards digital video communication at the expense of face-to-face interaction as it allows for less information (Hammersley et al. Citation2019). This loss of information is also a relevant drawback for written digital communication that can complicate communication.

Several researchers point to the need for the social work profession to develop and implement new skills related to digital interaction (LaMendola Citation2019; López Peláez, Pérez García, and Aguilar-Tablada Massó Citation2017). This article contributes to the growing research on digitalization and social work from a socio-technical standpoint by examining a digital platform used in practice. This knowledge is essential as platforms in which social workers interact with clients are developed continuously in different areas of social work (Goldkind and Wolf Citation2015; Boddy and Dominelli Citation2017).

Platform social work

The term ‘platform social work’ is used in this article to refer to social work practices in various ways related to digital platforms. According to Gorwa (Citation2019), platforms facilitate access to user-generated content, and the term ‘platform’ refer to diverse online, data-driven apps and services. Digital platforms are used for various purposes like entertainment, news, transportation, accommodation, and job-seeking. While platforms in the private sector both collect and spread data and user-created content that can be shared with large audiences, this is not the case with platforms for client interaction in social work.

The use of digital platforms has extended in such a way that some researchers bring up the concept of a platformization of society. Van Dijck, Poell, and De Waal (Citation2018) describe this as a significant societal shift and, according to de Reuver, Sørensen, and Basole (Citation2018), digital platforms are transforming almost every aspect of society today. Digital platforms in social work are highly relevant as public sector platforms gain ground (Van Dijck, Poell, and De Waal Citation2018). Some of these are developed in close association with private companies. The case in this study, the Digital Activity Plan (DAP), is developed and owned by the Norwegian welfare and labour administration (Nav). Norwegian Child Protection Services is developing a digital service platform to communicate with children and families in need of their services (Digibarnevern). Other public institutions in Norway choose to buy existing platforms from private companies like Google (Trondheim Municipality) or the American IT company Epic (Helseplattformen). Regardless of ownership, the platforms are often made up of ubiquitous socio-technical assemblages – impacting practices and spreading far into the domain of social work in novel ways. Van Dijck, Poell, and De Waal (Citation2018) argue that the disruptive effects of the digital platforms are hiding a system of logistics as well as logic. In scrutinizing DAP, this article will examine how this can also be said about platforms used in social work practice.

Theoretical framework: socio-technical assemblages and affordances

Social work is complex and rife with dilemmas; issues relating to technology in this field are equally complex (Mackrill and Ebsen Citation2018). Having a socio-technological perspective provides a lens to investigate in detail how professional practices, together with structural aspects like key political and economic factors, influence the development of the data systems in a way that preserves this complexity while detangling the socio-technical assemblages. In this article, digital platforms are conceptualized as a socio-technical assemblage that includes technical elements, as well as the associated organizational processes and standards (Tilson, Sorensen, and Lyytinen Citation2012). The evolution of technical infrastructure is, therefore, just as much a social as a technological phenomenon.

The relationship between artefacts and humans is considered symmetric in terms of their mutual impact on each other (Winner Citation1980). In researching digital technology, the researcher therefore, needs to take into account both the technology and the humans involved in shaping practices evolving it. The platform explored in this article consists of diverse functionalities and design elements integrated into political, social, and legal contexts, as well as infrastructures and meaning-making. The result of this entanglement of the social and material can be seen as what Suchman (Citation2007) refers to as a socio-material assemblage. In these assemblages, a combination of heterogeneous components, inclusive techniques, logics, practices, material agents, and humans form social structures and relationships. Redden, Dencik, and Warne (Citation2020) has, through research on artificial intelligence in child welfare systems, shown how socio-technical assemblages as a framework help reveal the richness and complexity of technology in social work practice.

A socio-technological perspective moves away from seeing technological artefacts as solely a passive tool solving a problem. Yet technology is often developed with the intention of solving issues by enabling possibilities for action. Affordances was originally a term used by evolutionary psychologist Gibson (Citation1986), who defined affordances as ‘action possibilities’ that arise in the interaction between an animal and its environment. The concept of affordances has since been adapted for use in studies of human-computer interaction. Here the term focuses on affordances as a way to explore the relationship between technology and organizational actors (Bygstad, Munkvold, and Volkoff Citation2016). In this sense, affordance emerges from the relation between the technology and other actors and is thereby not solely related to the features of the technology. According to Islind et al., Citation2019, affordances are dynamic and emerge through interaction between the actors and their surroundings, making them neither the properties of the environment nor the characteristics of the individual actors.

In this article, affordance is used to describe possibilities of action in the multi-dynamic relationship between DAP and its users and includes both social and political contexts. While affordances are possibilities for action that arise from the interaction of the components, the socio-technical assemblages are a way of describing the complex entanglements of a multitude of actors, including the technology that takes part in evolving the practices and values integrated into them.

Data and method

The research on DAP is part of a case study that aims to investigate how the use of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) in social work can affect the practice. The study is based on an analysis of multiple sources of qualitative empirical data. The study is approved by the Norwegian Social Science Data Service. All data material collected is treated following the Norwegian Social Science Data Service’s ethical requirements.

The initial data collection consisted of ethnographic observations at a Nav office conducted over eleven days in January and February 2020. The observations were exploratory, and the author followed counsellors working in DAP. Informants showed different plans for clients, examples of digital communication, and answered messages they received. This provided an opportunity to ask questions based on a pre-prepared interview guide, follow up with more detailed questions, and look at examples. The counsellors who participated as informants belonged to various departments that focused on different target groups. Observations of team meetings, the front service desk, and group meetings during which clients were taught how to use DAP were also a central part of the fieldwork.

The field study was followed up with eleven individual semi-structured interviews, based on findings from the ethnographical observations, as well as research questions. Collecting data through interviews about the subjects’ experiences allows pursuing topics that emerge during the interview (Morgan Citation2017). This is important because there is limited existing knowledge about digital communication with governmental social work organizations. Topics in interviews addressed practices related to DAP, how it changed their professional role, and what kind of experiences they had in co-operating with clients on the digital platform.

The sample for the individual interviews consisted of counsellors from five Nav offices. Two offices were relatively large and located in a larger municipality, while the others were smaller offices in peripheral municipalities. The informants participating in individual interviews had all been employed in Nav for more than a year. All had completed higher education, some in social work and others in health care, psychology, or pedagogy.

Stepwise-deductive induction (SDI) was chosen for analysing the findings (Tjora Citation2019). This method is inductive as it works from data to theory. Multiple sources of data generate thick descriptions, and a combination of deductive and inductive strategies gives room for the nuances in the empirical material along the process. Empirically close coding was used to analyse the field notes before the individual interviews, and in this way, the process gave room to influence the topics addressed in these interviews. The interviews were coded closely related to the transcribed material after transcription, and in this way important nuances in the material were not lost. Nvivo, a computer program for analysing data, was used to manage the coding. The initial analysis resulted in a magnitude of codes closely corresponding to the informant’s statements, which made using a computer program for coding essential. In the next step of the analysis, the inductively based codes were then sorted into coding groups related to this article’s research question. These codes revolved around the different functions of DAP and how they influenced the practices.

SDI has a way of downward feedback from the more theoretical to the more empirical, which also makes it a deductive process (Tjora Citation2019). In the last step of the coding, six overarching categories inspired by affordance theory were established. These identified platform affordances that impacted the counsellors’ work practices and will be presented and discussed in the analysis section of this article. The excerpts from interviews and observations were included following a review of the initial codes after establishing the affordances coding groups and sorting the initial codes in these groups.

Findings and discussion

Drawing from this concrete case study, the impact of platformization on social work and negotiations of platform affordances will be investigated. The following research questions are addressed by a thorough presentation of DAP before each of DAP’s multiple affordances are discussed: In what ways do counsellors’ roles and practices change because of the introduction of DAP? What new challenges and possibilities lie within the platform, and how are these affordances negotiated and shaped in practice?

Digital activity plans in Nav

Nav is one of the governmental agencies that has made large-scale investments in digital technology over the last decade. The counsellors at Nav have experienced an immense digital transformation and, according to Nav’s own analysis, the development will continue.

«Also for NAV, digitalization will continue to move user dialogue and service production to digital surfaces. Not only in the processing of applications but also in work inclusion services» (Nav Citation2021a, 42).

Nav has established several ways of interacting with clients online. Digital application processes and case management systems are developed to promote casework effectiveness and provide better services. DAP is one of the new digital tools available for clients and employees of Nav. It was introduced in late 2017 and aims to facilitate planning activities and digital communication between clients and their counsellors. DAP replaced the former activity plan written by the counsellor in the internal computer system and then printed and mailed to the client for their signature.

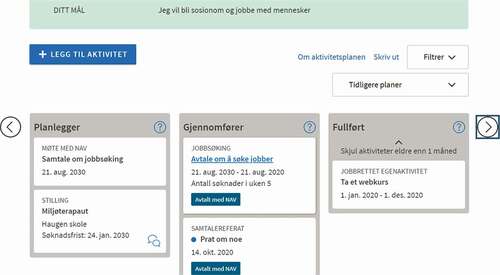

All clients who receive work-oriented follow-up have access to a digital messaging service and a planning tool through DAP. While the clients enter the platform via Nav’s webpage, counsellors access through their case management system. However, the functions they access are similar when it comes to written digital messages. Through a chat-like function called ‘The Dialogue’, both counsellors and clients can start conversations on self-chosen topics related to their collaboration. The other part of DAP is the activity plan, built by activity cards. An activity card consists of any activity related to the client’s efforts to enter the labour market, and what activities are considered relevant will depend on the client’s situation.

The cards can be created either by the counsellor or by the client. The system also provides some automatic suggestions. Anything from meetings at the NAV office, different kinds of health treatments, activation programmes, job-seeking efforts, health/fitness activities and educational programs can be a part of the plan. Norwegian classes could be an activity card for clients with low language skills, and working out could be an activity card for clients struggling with health issues due to obesity. Each job advertisement a client applies for can also be put in their activity plan as an activity card. In other words, there are very diverse purposes in the activity card’s content. Some of the activity cards can be marked as ‘Agreement with Nav’, and violating this commitment can, in some cases, have consequences for a client’s financial support.

DAP serves as the client’s journal where reports from meetings are written. When a physical meeting is planned, the counsellor makes an activity card for the meeting in DAP. Details about the meeting, like where it is held and the agenda, are shown on the activity card. After the meeting, the counsellor writes a report stating what was discussed and what they agreed upon. A completed report is visible to the client, who can then respond to the content by making comments on the activity card of the meeting. In some cases, the counsellors can also ask the client to write the report themselves. In this regard, clients are included in what were previously ‘back-office’ activities. All reports should be written in DAP, but reports are written in the closed IT system that only the counsellor has access to in rare cases. According to the fieldwork informants, this occurs when clients have a history of violence towards previous counsellors.

DAP enables digital communication between the counsellors and their clients, becomes an arena for counselling, serves as a contract between the client and Nav, and stores information. The data collected is measured to monitor developments in activities at an organizational level. As I will elaborate upon in the discussion, DAP also functions as a political instrument to enhance activation policies. In the following sections, the various socio-technical affordances of DAP are discussed in light of the informant’s experiences.

DAP enabling communication

DAP is a platform meant to facilitate digital communication between clients and their counsellors. The accessibility DAP gives them in communicating has clear advantages. Both during fieldwork and in some of the interview’s informants used the word ‘Cheerleader’ in relation to their new practices because of DAP. The ability of counsellors to follow the client more actively from the sideline through messages, which the client can respond to, gives a new opportunity for connection.

The implementation of DAP greatly impacts the informants’ practices when communicating with clients. One informant describes how technology has become the driving force at the expense of focusing on communication and relational practices when she says, ‘DAP is like a digital locomotive – you better hold on’. The informants’ experience changes the way they organize their work, as a lot of the communication moves from face-to-face or on the telephone to a digital platform. Depending on the topic, this can have advantages or be clearly problematic. During the fieldwork, some informants showed me examples of digital communication with extensive asynchronous chat logs. Sometimes it could be hard to understand what the client wanted, or the clients misunderstood the counsellor’s messages. The counsellors could then change the channel of communication. One informant explains that:

Digital communication is nice and such when we have a common understanding of what is going on. When that starts to get a little messy, I rather pick up the phone or set up a meeting.

Another dilemma that surfaced during fieldwork, was the way counsellors chose between more standardized scripts and individually adapted communication in the DAP. Some clients were comfortable with written communication, and sometimes they could express their thoughts and describe their situation better in a digital chat. Others had lower levels of digital skills and found even logging into the plan to be difficult. To the informants, it was important to adjust their use of DAP to individual clients’ needs and resources.

The implementation of DAP caused the counsellors to need to develop new skills both in digital counselling and in discretionary practices regarding how to use multiple communication channels. Digital channels, and the affordances of rapid digital messaging, allow the counsellors to stay connected to more people. At the same time, the use of digital channels can be resource-intensive when misunderstandings and ambiguities arise. If the intentions with the digitalization of services are to contribute to achieving the goal of efficient resource utilization and more active users, it is crucial that the counsellors make good assessments regarding the choice of communication channel.

DAP as an arena for counselling

Nav counsellors communicate with clients on a wide range of topics. Some topics are related to practical arrangements and benefits, while others are related to supporting decisions in career choices or challenging life situations. Motivational and counselling skills are considered necessary in handling these topics (Nav Citation2021b). According to the informants in the study, there has been a shift from face-to-face meetings towards a digital arena. Most of the informants during the field observation reported fewer physical meetings, and in the individual interviews that took place after the COVID-19 pandemic, this shift was even more apparent. The informants believed that even though the social distancing policies would end, this change would continue to a certain degree. This gives DAP the affordance of serving as an arena not just for informing about application processes or benefits but also for counselling.

One of the core intentions with DAP is to engage clients to participate in administering their own activity plan. The digitalization of DAP enables interactional participation in the plan in a new way. To take advantage of this possibility, the informants consider it essential to be able to motivate the client to take ownership of the plan. Encouraging this ownership was also addressed in several team meetings during the fieldwork and among informants during observations and interviews. Web technologies take a central part in participation in what Eriksson (Citation2012) labels the self-service society. They make it possible to organize public administration in a consumer-oriented fashion-based increasingly on individual activity, where the state withdraws from welfare politics deemed patronizing. Emphasizing personal responsibility along with the goal of reducing bureaucracy, individual actors are supposed to become self-directed. The focus on participatory elements of the activity plan is defined in a white paper (Ot.prp.nr.4 Citation2008–Citation2009) that states the plan is supposed to involve the clients in their process towards the labour market. The argument behind this is that motivation and participation are viewed as essential factors in succeeding in these efforts.

Many of the informants were concerned with recognizing the clients that could ‘help themselves’ by using digital solutions so they could spend their time on clients who needed them the most. Zhu and Andersen’s (Citation2020) research on ICTs in Nav found that digital interaction can empower clients and promote their participation, provided they have relevant resources, competence, and motivation to have an overall positive experience with ICT-mediated communication and service. This shows the expectations not only towards counsellors but also the clients change as a result of the digital transformation.

Empowering practices along with motivational skills is central in many of the informant’s educational backgrounds. How these skills are practiced in digital counselling was a central topic in the interviews. At the top of the digital activity plan, and typically, the first thing you see when you log in is a text box with the heading ‘My goal’. Here clients are expected to articulate the goal of their collaboration with Nav. One of the informants during observation demonstrated how she used this part of DAP to introduce life goals as a topic and tried to find ways to address it in an empowering manner. Most of the informants were still hesitant in the question of whether DAP has motivational and empowering functions. One of them stated:

No, I don’t think it contributes to motivation, to be honest. I wish it did, but I don’t see people getting a lot of motivation from the activity plan. I think they get motivated because of the feedback we give them, but I don’t think DAP is promoting motivation in itself.

The informant makes an important distinction when she points out ‘not in itself’, which also relates to the informant discussing how she uses DAP in meetings with clients. This relates to the socio-technical understanding of affordance as what happens in interaction with users and not always what its designers intend. The quote illustrates what Granholm (Citation2016) refers to as ‘blended services’ that lie in the intersection between social work and ICT. In line with research in this article, she claims that social work in the time of digital transfer is characterized by the simultaneous presence in both online and offline dimensions. Findings from this study indicate that creating synergy effects from blended services can generate new possibilities for support and participation. However, that is under the condition that counsellors have the time and skills to make critical reflections and individual adaptions to adjust to diverse clients and situations.

DAP as an information system

Counsellors access data about their clients, and clients find information about their own case in DAP. An important affordance of DAP is therefore serving as an information system. According to Flyverbom and Murrey (Citation2018), how data are structured, sorted, and curated is an important question to research because these socio-technical arrangements shape what becomes visible, knowable, and actionable. Data infrastructures come across as technical and relatively neutral to the degree that they are easily taken for granted.

Data captured in DAP range from information about jobs the client applied for or courses they attended to more sensitive data like medical treatment or social problems that need to be addressed. The content is created by both the client and the counsellor. The informants using DAP as a portal to find required information question how easily accessible the information is. Clients labelling the chat logs and having several places in the plan where they can write, make it challenging to sort valuable and necessary information from less important information. During observations, the informants also spent quite a lot of time ‘cleaning up the activities in the plan’ to update current activities in each client’s plan.

Although several informants are concerned about how to motivate the client to ‘take ownership’ of the plan, who is actually in charge of administrating the plan is somewhat unclear. Managers and other employees at Nav can access the data entered in DAP, and there is limited access to deleting activity cards and reports both for the client and the counsellor. However, clients writing reports in DAP are being put in charge of how the information about them is presented in the systems. Accessing the plan digitally also makes it possible for clients to access the data registered about themselves and comment when they disagree, which is considered central to the protection of their legal rights. The clients also meet changed expectations on how to report and communicate with Nav. Several of the informants were concerned that some clients are not aware of the data they put into the systems and how it is used. For many clients, the dialogue appears to be a way to send updates and questions directly to the counsellor they have a close connection to. That these messages can be read and interpreted differently by other employees at a later point is not something the clients necessarily reflect upon, according to some informants.

Barsky (Citation2017) claims that the way social workers collect troves of personal and sensitive data about clients raises ethical issues about confidentiality. Barsky encourages asking who is authorized to access the information gathered, transmitted, managed, or stored as part of ethically investigating practices evolving new technology. The information handling is an affordance of DAP over which several of the informants raise concerns. Clients who write in the dialogue part of DAP can be in challenging life situations; what they write gives a picture of the moment meant for only their trusted counsellor. In contrast, the counsellors are aware that what they write will be registered in the system and might be read by other Nav employees at a later point. Some informants fear this might contribute to stigmatizing the client.

In previous research, social work organizations have been heavily criticized for handling personal information in questionable ways (Eubanks Citation2018; Redden, Dencik, and Warne Citation2020). The informants in this study also experienced that registered data could lead to negative sanctions for the client. How the registered information is used at an organizational level will be further discussed in the following sections.

DAP as a contract

As mentioned, DAP serves as a contract between clients and Nav by stating the commitments in activity cards. The relationship between the citizen and the state has become increasingly contractual (Andersen Citation2007). Contract-based rights, where the connection between rights and obligations is clarified, have become more common in Norway in recent years (Åsheim Citation2018). Nav’s activity plan serves as a good example of this. Conditions of activity manifested in DAP are linked to several welfare benefits, and the right to participate in the preparation of the plan is regulated by law (NAV law §14A).

An informant working with clients that are supposed to manage to apply for jobs themselves and mostly get digital help from Nav; says that all of these clients are required to apply for jobs. This is a standard activity card with standardized text, but counsellors make a discretionary assessment of the number of applications required per week. Counsellors also enter a warning that makes it possible to stop benefits if clients do not report job applications every 14 days. Hagelund et al. (Citation2016) describes the sanctioning regimes towards clients who fail to fulfill or maintain a prescribed activity implemented as a result of work-first policies and activation measures. They argue that most sanctioning regimes comprise three elements: the first for registering and transmitting information regarding compliance/non-compliance, the second for issuing warnings, and the third for implementing sanctions. In Nav, DAP is the system for the first two elements: it registers whether activities are completed, and the counsellors use it to issue warnings.

Counsellors function as street-level bureaucrats as they are the frontline workers of the welfare state, providing public services, interacting with citizens, and exercising discretion in ethical and value-laden questions (Lipsky Citation2010). As a part of this role, counsellors have an executive function in triggering sanctions. Several informants found the sanctioning part of the job challenging. DAP changed the terms for conducting sanctions. Some of the case handling revolving sanctions became supposedly more ‘automatic’, and DAP collected more information about compliance/non-compliance of the required activities. Managing sanctions towards clients was not new, but DAP impacted the structures of how it was done. An aspect a few informants worried about related to this was that clients might not be able to fulfill expectations expressed in DAP because of a lack of digital skills. Another aspect regarding the sanctioning some informants worried about was, as several informants put it, ‘how much pressure’ they could express in DAP. Their role consisted of trying to form a helpful relationship with their clients while at the same time having a strong control function regarding the compliance of benefits. Previous discussions about sanctioning benefits mainly had been done face-to-face, allowing the informants to pick up feedback and adjust communication to express empathy and avoid misunderstandings. The duality of the relationship between counsellor and client became more complicated when intervened in a digital platform.

Not all activity cards require fulfiling obligations to receive benefits. The client can make their own activity cards for any activity they consider important for their situation and different kinds of efforts to enter the labour market. According to the informants, this is a function many of their clients do not use. Their explanation is that some clients fear doing something wrong that can break the contract and impact their benefits or support from Nav.

Olesen’s (Citation2018) research on Nav’s activity plan (before digitalization) analyses the activity plan as a governance document meant to ensure user participation and empowerment. He simultaneously claims the document activates neo-liberal and pastoral logics between client and counsellor. The most significant difference between the old paper version of the plan and DAP is the possibility of continuous surveillance of the client’s activities. Digital platforms serving as tools of surveillance have been well documented through the work of Soshanna Zuboff (Citation2019), among others. Garrett (Citation2004) claims the field needs to examine the control aspects of social work in the emergence of surveillant practices. The findings from this study underline how the digital transformation creates new frameworks and spaces for both the help and control aspects of social work and draws new lines for the sometimes-fragile border between the two concepts.

DAP as a measuring tool

Aspects of a client’s activities and status, as well as the counsellor’s performance, are registered in DAP and can be measured at both individual and organizational levels. When registered correctly, data from activity plans can measure aspects like the number of unemployed users in some kind of activity, the number of meetings counsellors have with clients or the number of job applications the average client sends. The rise of online platforms intensifies data collection practices about activities, objects, and relations that were not previously quantified (Van Dijck, Poell, and De Waal Citation2018). The measurements in DAP are an example of this. Some individual client activities were previously registered in information systems, but DAP amplifies these registrations and the possibility to showcase them at both a client or counsellor level.

During fieldwork, the management’s focus was on registering the activities of most clients; DAP calculated the percentage of clients in activity. According to Mau (Citation2019), contemporary obsessions with quantification leads to counting what can be counted, not necessarily what is important. Some of the informants found that the focus on registering could take priority away from more important activities in collaboration with the client. One informant says she considers how actively she will focus on making the client use the plan as to whether this is the best way to help them. She also states that:

There are not very many I have seen who feel that this plan is a fantastic tool for getting a job. It is not.

The measured aspects of the work sometimes set strict frameworks for prioritizing and executing social work interactions and lead to a situation where what is measured counts. An example of how measuring as an affordance in DAP can change priorities is that a few of the informants’ clients sent digital messages frequently. Response time for messages was one of the measurements the managers emphasized. The informants feared this could lead to prioritizing clients with high digital skills at the expense of less resourceful clients. The extended ability of digital platforms to measure could lead to a situation where quick results measured in the organization become a more attractive goal than working on more long-term goals with clients.

It is not only the measurement of social workers’ performance that has become common practice in social work, but also characteristics regarding the clients are included in different kinds of digitally facilitated assessments (Hoybye-Mortensen Citation2015; Mik-Meyer Citation2018). DAP includes both of these, and the measurements are used both at an individual and organizational level. At an organizational level, data registered in DAP is used both for policymaking and for managers to supervise their employees. MacDonald (Citation2006) argues that performance measurement of social work is built on an ideology of distrust against public servants and professions. Neoliberalist inspired standardization and management through objectives is seen as in opposition to traditional social work, where autonomous interactions are seen as dependent on professional skills and expertise.

DAP as a political instrument

Van Dijk, Poell, and De Waal (Citation2018) argue that digital platforms hide a system of logistics as well as logic, and conceptions of common good are attached to these logics. In this way, elements of platforms steer social norms. Technology can be intended to nudge certain behaviour considered favourable by its makers. DAP is not only supposed to help people keep track of their job applications and report this to Nav but also encourages them to apply for more vacant positions. This quote from Nav’s report on future risks and possibilities illustrates this well:

In the same way that the placement of the candy shelf in the grocery store influences what ends up in the shopping cart, the choice in architecture, digital surfaces and processes can be designed with the goal of changing people’s behaviour in a desired way, for example in the digital activity plan to help clients into work. (Nav Citation2021a, 41)

The quote reveals the political intentions of activation embedded in DAP. This demonstrates how digital welfare state technologies reflect political choices. Winner (Citation1980) discusses whether or not material-technical artefacts are intrinsically political and argues that they are. In the way, artefacts embody social relations, they are not only judged for their efficiency and productivity but also for how they can embody specific forms of power and authority. It might seem apparent that technical systems are deeply interwoven in conditions of modern politics, but Winner goes on to argue that certain technologies in themselves have political properties. He links this to institutionalized patterns of power and authority. This could be an aspect of intentions or design elements. Using DAP as an example, the way the platform enables digital communication between governmental agencies and citizens implements the ‘digital by default’ strategy in the public sector. But the political inscriptions go further than this, as activation policies are inscribed in the design of DAP.

In Norway, activation intervention and the so-called ‘work-first’ policy is considered the primary tool for fighting poverty and marginalization, and Nav plays a vital role in conducting this policy (Meld. St. 46 (Citation2012–Citation2013)). There are three fundamental features in the activation concept in the European intervention paradigm, according to Pascual (Citation2007): an individual approach, emphasis on employment, and contractualization. These features are also prominent in Norwegian activation measures (Hansen and Natland Citation2017). The previous section discussed how DAP plays an important role in contractualization, but the emphasis on employment is also deeply embedded in DAP functions. By encouraging the setting of individual goals and the definition of activities necessary to achieve the goals, DAP aims to assist the client towards inclusion into the labour market. Although standardized activity cards were quite prevalent during the fieldwork, the plan is supposed to be tailored to each client’s needs (Nav law §14). Some of the informants also underline the importance of individual adaptation. In this way, DAP also reflects the individual approach that Pascual (Citation2007) describes as fundamental in the European activation concept.

This shows how policies are entangled together with design elements, affordances as well as work practices, and values into socio-technical assemblages. This underlines the need for practitioners to be aware of the technical components they interact with as they contain underlying political intentions.

Concluding remarks

DAP is intertwined in both the case handling practices and interactions with clients for counsellors in Nav. As the digital transformation progresses, it will be necessary for social work practice and research to find ways to investigate the mutual impacts between technology and social work by detangling these assemblages.

Digital contact with clients can support interactions, and both underline and challenge social work’s traditional goals and values in various ways. As social workers in general, counsellors at Nav have complex roles: street-level bureaucrats who are supposed to function as gatekeepers for social benefits as well as to motivate and help clients in their struggles to enter the job market. This tension between help and control is characteristic of social work as a profession. The two concepts are intertwined and interdependent in social work practice. The digital platform where social workers and clients interact impacts both how they manoeuvre in this space and sets new terms for it. Dencik and Kaun (Citation2020) describe a shift towards a new regime in public services and welfare provision that is intricately linked to digital infrastructures and results in new forms of both control and support. The findings of this case study support this. The counsellors negotiate between expectations embedded in the platforms that are supposed to be empowering while at the same time serve as a control mechanism. On the one hand, DAP is supposed to enable a helping process that empowers the client and making interaction accessible and easy. On the other hand, DAP acts as a contract between Nav and the client, and violating this contract can have financial consequences for clients relying on benefits.

The key point in this article is that social work, both as a practice field and as a research field, needs to be aware of how the socio-technical assemblages in these platforms have political impacts and influence practices in unintended ways. These findings have implications for both social work research and practice. The examples from this research also illustrate the impact digital services have on the need for both new knowledge production and skills in social work practice due to the digital transformation. Another consequence of viewing technology as an actor in social work practices is that the profession needs to take an active part in the development of digital tools.

The article displays the different affordances of DAP through a case study. An in-depth analysis of each, as well as features of other platforms used in social work practice, is necessary to show how platforms take part in socio-technical assemblages that intertwine and impact both social policy and social work practices. Platforms allow both new ways of sharing and new social forms, and with platformization they extend to a variety of societal areas (Van Dijck, Poell, and De Waal Citation2018). For social work, the rise of platforms connects to discussions with a long tradition in the field, like the dichotomy between help and control and the individualization of social problems. However, not only does it deepen existing dilemmas of the field, but it also creates new ones. Surveillance practices, the use of data to nudge certain behaviours, and ethical concerns involving ownership and access of data are important examples that need closer examination. Technology is not a politically or morally neutral factor in the implementation of social policy. The impacts on both social work practice and social issues as a result of this should be investigated further.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. Counsellor is the official term for employees in Nav working at the local offices that support and give guidance to clients. In this article the term ‘counselor’ is used when talking about Nav employees. ‘Social worker’ is used when addressing the profession in general.

References

- Aguilar-Idañez, M.-J., N. Caparrós-Civera, and S. Anaut-Bravo. 2018. “E-social Work: An Empirical Analysis of the Professional Blogosphere in Spain, Portugal, France and Italy.” European Journal of Social Work 23 (1) 1–13.

- Andersen, N. Å. 2007. “Creating the Client Who Can Create Himself and His Own Fate – The Tragedy of the Citizens’ Contract.” Qualitative Sociology Review 3 (2): 119–143. doi:10.18778/1733-8077.3.2.07.

- Åsheim, H. 2018. “Aktivitetsplan som styringsverktøy.” Søkelys på arbeidslivet 35 (4): 242–258. doi:10.18261/.1504-7989-2018-04-01.

- Barsky, A. E. 2017. “Social Work Practice and Technology: Ethical Issues and Policy Responses.” Journal of Technology in Human Services 35 (1): 8–19. doi:10.1080/15228835.2017.1277906.

- Best, P., R. Manktelow, and B. J. Taylor. 2014. “Social Work and Social Media: Online Help-seeking and the Mental Well-being of Adolescent Males.” The British Journal of Social Work 46 (1): 257–276. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcu130.

- Boddy, J., and L. Dominelli. 2017. “Social Media and Social Work: The Challenges of a New Ethical Space.” Australian Social Work 70 (2): 172–184. doi:10.1080/0312407X.2016.1224907.

- Bryant, L., B. Garnham, D. Tedmanson, and S. Diamandi. 2018. “Tele-social Work and Mental Health in Rural and Remote Communities in Australia.” International Social Work 61 (1): 143–155. doi:10.1177/0020872815606794.

- Bygstad, B., B. E. Munkvold, and O. Volkoff. 2016. “Identifying Generative Mechanisms through Affordances: A Framework for Critical Realist Data Analysis.” Journal of Information Technology 31 (1): 83–96. doi:10.1057/jit.2015.13.

- Chan, C. 2016. “A Scoping Review of Social Media Use in Social Work Practice.” Journal of Evidence-Informed Social Work 13 (3): 263–276. doi:10.1080/23761407.2015.1052908.

- de Reuver, M., C. Sørensen, and R. C. Basole. 2018. “The Digital Platform: A Research Agenda.” Journal of Information Technology 33 (2): 124–135. doi:10.1057/s41265-016-0033-3.

- Dencik, L., and A. Kaun. 2020. “Datafication and the Welfare State.” Global Perspectives 1 (1). doi:10.1525/gp.2020.12912.

- Devlieghere, J., R. Roose, and T. Evans. 2020. “Managing the Electronic Turn.” European Journal of Social Work 23 (5): 767–778. doi:10.1080/13691457.2019.1582009.

- Eriksson, K. 2012. “Self‐service Society: Participative Politics and New Forms of Governance.” Public Administration 90 (3): 685–698.

- Eubanks, V. 2018. Automating Inequality: How High-tech Tools Profile, Police, and Punish the Poor. First Edition. utg ed. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press.

- Flyverbom, M., and J. Murray. 2018. “Datastructuring—Organizing and Curating Digital Traces into Action.” Big Data & Society 5 (2): 2053951718799114. doi:10.1177/2053951718799114.

- Garrett, P. M. 2004. “The Electronic Eye: Emerging Surveillant Practices in Social Work with Children and Families.” European Journal of Social Work 7 (1): 57–71. doi:10.1080/136919145042000217401.

- Garrett, P. M. 2005. “Social Work’s ‘Electronic Turn’: Notes on the Deployment of Information and Communication Technologies in Social Work with Children and Families.” Critical Social Policy 25 (4): 529–553. doi:10.1177/0261018305057044.

- Gibson, J. J. 1986. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Gillingham, P. 2018. “Developments in Electronic Information Systems in Social Welfare Agencies: From Simple to Complex.” The British Journal of Social Work 49 (1): 135–146. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcy014.

- Goldkind, L., and L. Wolf. 2015. “A Digital Environment Approach: Four Technologies That Will Disrupt Social Work Practice.” Social Work 60 (1): 85–87. doi:10.1093/sw/swu045.

- Gorwa, R. 2019. “What Is Platform Governance?” Information, Communication & Society 22 (6): 854–871. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2019.1573914.

- Granholm, C. P. 2016. “Social Work in Digital Transfer - Blending Services for the Next Generation.” PhD. thesis. University of Helsinki.

- Hagelund, A., E. Øverbye, A. Hatland, and L. I. Terum. 2016. “Sanksjoner–arbeidslinjas nattside?” Tidsskrift for velferdsforskning 19 (1): 24–43. doi:10.18261/.2464-3076-2016-01-02.

- Hammersley, V., E. Donaghy, R. Parker, H. McNeilly, H. Atherton, A. Bikker, J. Campbell, and B. McKinstry. 2019. “Comparing the Content and Quality of Video, Telephone, and Face-to-face Consultations: A Non-randomised, Quasi-experimental, Exploratory Study in UK Primary Care.” The British Journal of General Practice: The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners 69 (686): e595–e604. doi:10.3399/bjgp19X704573.

- Hansen, H. C., and S. Natland. 2017. “The Working Relationship between Social Worker and Service User in an Activation Policy Context.” Nordic Social Work Research 7 (2): 101–114. doi:10.1080/2156857X.2016.1221850.

- Hill, A., and I. Shaw. 2011. Social Work and ICT. London: SAGE.

- Hoybye-Mortensen, M. 2015. “Decision-Making Tools and Their Influence on Caseworkers’ Room for Discretion.” British Journal of Social Work 45 (2): 600–615. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bct144.

- Islind, A. S., U. L. Snis, T. Lindroth, J. Lundin, K. Cerna, and G. Steineck. 2019. “The Virtual Clinic: Two-sided Affordances in Consultation Practice.” Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW) 28: 435–468 doi:10.1007/s10606-019-09350-3.

- Lagsten, J., and A. Andersson. 2018. “Use of Information Systems in Social Work–challenges and an Agenda for Future Research.” European Journal of Social Work 21 (6): 850–862. doi:10.1080/13691457.2018.1423554.

- LaMendola, W. 2019. “Social Work, Social Technologies, and Sustainable Community Development.” Journal of Technology in Human Services 37 (2–3): 79–92. doi:10.1080/15228835.2018.1552905.

- Lipsky, M. 2010. Street-level Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Service Russell. New York: Sage Foundation.

- López Peláez, A., R. Pérez García, and M. V. Aguilar-Tablada Massó. 2017. “E-social Work: Building a New Field of Specialization in Social Work?” European Journal of Social Work 21: 6 804–823 doi:10.1080/13691457.2017.1399256.

- Mackrill, T., and F. Ebsen. 2018. “Key Misconceptions When Assessing Digital Technology for Municipal Youth Social Work.” European Journal of Social Work 21 (6): 942–953. doi:10.1080/13691457.2017.1326878.

- Mau, S. 2019. The Metric Society: On the Quantification of the Social. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons.

- McDonald, C. (2006) ”Institutional transformation: The impact of performance measurement on professional practice in social work”, Social Work & Society 4 (1): 26–37

- Meld. St. 46. 2012–2013. “Flere i arbeid.” Arbeids- og sosialdepartementet

- Mihai, A., G.-C. Rentea, D. Gaba, F. Lazar, and S. Munch. 2016. “Connectivity and Discontinuity in Social Work Practice: Challenges and Opportunities of the Implementation of an E-social Work System in Romania.” Journal of Comparative Research in Anthropology Sociology 7 (2): 21.

- Mik-Meyer, N. 2018. “Organizational Professionalism: Social Workers Negotiating Tools of NPM.” Professions and Professionalism 8 (2): e2381–e2381. doi:10.7577/pp.2381.

- Miller, J. J., M. Cooley, C. Niu, M. Segress, J. Fletcher, K. Bowman, and L. Littrell. 2019. “Virtual Support Groups among Adoptive Parents: Ideal for Information Seeking?” Journal of Technology in Human Services 37 (4): 347–361. doi:10.1080/15228835.2019.1637320.

- Ministry of Local Government and Modernization. 2019. “En Digital Offentlig Sektor, Digitaliseringsstrategi for Offentlig Sektor, 2019–2025.”

- Morgan, D. L. 2017. Integrating Qualitative and Quantitative Methods: A Pragmatic Approach. London: SAGE Publications.

- Nav. 2021a. “Navs omverdensanalyse 2021.” NAV-rapport nr. 1–2021

- Nav. 2021b. “Veiledningsplattformen, Navs intranett Navet.”

- Nesmith, A. 2018. “Reaching Young People Through Texting-Based Crisis Counseling.” Advances in Social Work 18 (4): 1147–1164. doi:10.18060/21590.

- Olesen, E. S. 2018. “Medbestemmelse og umyndiggørelse.” Tidsskrift for velferdsforskning 21 (4): 330–346. doi:10.18261/.2464-3076-2018-04-04.

- Ot.prp.nr.4. 2008–2009. “Om lov om endringer i folketrygdloven og i enkelte andre lover (arbeidsavklaringspenger, arbeidsevnevurderinger og aktivitetsplaner).” Arbeids- og sosialdepartementet.

- Pascual, A. S. 2007. “Reshaping Welfare States: Activation Regimes in Europe.” In Reshaping Welfare States and Activation Regimes in Europe, edited by P. Amparo Serrano and L. Magnusson, 11–34. Brussels: P.I.E.

- Redden, J., L. Dencik, and H. Warne. 2020. “Datafied Child Welfare Services: Unpacking Politics, Economics and Power.” Policy Studies 41 5 507–526 doi:10.1080/01442872.2020.1724928.

- Røhnebæk, M. (2014). Standardized Flexibility: On the Role of ICT in the Norwegian Employment and Welfare Services (NAV) PhD. Thesis, Centre for Technology, Innovation and Culture, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Oslo, Oslo.

- Suchman, L. 2007. Human-machine Reconfigurations: Plans and Situated Actions. Cambridge: Cambridge university press.

- Tilson, D., C. Sorensen, and K. Lyytinen. 2012. “Change and Control Paradoxes in Mobile Infrastructure Innovation: The Android and iOS Mobile Operating Systems Cases.” 2012 45th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences Hawaii. pp. s. 1324–1333. IEEE.

- Tjora, A. H. 2019. Qualitative Research as Stepwise-deductive Induction. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Van Dijck, J., T. Poell, and M. De Waal. 2018. The Platform Society: Public Values in a Connective World. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Winner, L. 1980. “Do Artifacts Have Politics?” Daedalus 109 1 121–136.

- Zhu, H., and S. T. Andersen. 2020. “ICT-mediated Social Work Practice and Innovation: Professionals’ Experiences in the Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration.” Nordic Social Work Research 346–360 doi:10.1080/2156857X.2020.1740774.

- Zuboff, S. 2019. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for the Future at the New Frontier of Power. London, New York: Profile Books Public Affairs.