ABSTRACT

This article examines child welfare students’ reflections on what they consider to be particularly important competence for a child welfare professional. Two hundred and two reflective papers written by child welfare students were collected and interpreted using thematic analysis. The analysis shows that relational competence was considered the most important competence and was elaborated on the most by students. The other areas of competence were not described in detail and there were few explanations as to how and why these competences are useful. Consequently, the child welfare professional’s theoretical competence and decision-making role are downplayed. The findings are relevant when discussing social work practice and education because the students’ understanding of their profession’s knowledge base might influence their professional identity and their readiness for work.

Introduction

The bachelor’s degree in child welfare is one of three social work degrees in Norway. Child welfare education (CWE) focuses particularly on work with children and adolescents living under conditions that represent a risk to their health and/or development.

A bachelor’s degree in child welfare qualifies graduates to work in e.g. the child welfare services (CWS). CWS work is considered very demanding (Skivenes and Tonheim Citation2016). It requires a high level of competence and a solid knowledge base in addition to the ability to make professional assessments. The service users are a heterogeneous target group and there is a wide range of reasons for intervention (Christiansen Citation2015). CWS work is known for its complex and value-laden dilemmas (Skivenes and Søvig Citation2017).

The education is composed of many different areas of knowledge that serve as the basis for a complex professional competence in line with society’s mandate, including professional ethical guidelines and academic standards. Professional competence is considered something that must be developed gradually and over time as experience is gained. The basis for such professional development should be established through education. The transition from education to practice is often perceived as demanding (Bates et al. Citation2010; Tham and Lynch Citation2020).

Research indicates that there is ambiguity about the most suitable knowledge base for social work (Oterholm, Citation2016; Trevithick Citation2008), the proportion of theoretical and practical courses in education (Tham and Lynch Citation2014), and how the competence of the professional correlates with good outcomes for children, adolescents and families (Lwin et al. Citation2018).

In this article, we examine child welfare students’ reflections on what they consider particularly important competence for child welfare professionals. The students in this study participated in a pedagogical project aiming to integrate theoretical knowledge, practical skills and personal competence in CWS casework. This was not a field placement, but a course developed in close collaboration with CWS in the local municipality. The students reflected on different aspects of professional competence and the significance of this for their future work.

The purpose of this study was to gain insight into how students perceive the competence of their profession. The students’ reflections are understood as an expression of their anticipation and construction of their professional identity. Professional identity is considered as developed by students through a socialization process where attitudes and values central to the profession they study become an integral part of the students themselves (Adams et al. Citation2006). Professional and practical implications for child welfare education and the transition to CWS work are discussed in the light of these findings.

Child welfare education in Norway

CWE is a bachelor’s degree in social work directed towards helping children, adolescents and families. The programme consists of both theory and practical elements. It qualifies graduates for a wide range of social work within the Norwegian welfare system.

The original national curriculum for CWE from 2005 was replaced by a new national curriculum in 2019 (Ministry of Education and Research Citation2005, Citation2019). The present study was conducted under the 2005 curriculum.

The national curriculum emphasizes that social work takes place in direct collaboration with individuals who need help, and that social work professions must work to identify and strengthen the resources of the individual and the family.

The national curriculum describes the child welfare professional`s knowledge base at an overall level and states the aims, goals and values of the education. The programmes must promote knowledge and attitudes based on humanistic views, human dignity, and human rights. Here, respect for the service user’s autonomy, experience and knowledge is central. The education must help students to practice their profession in line with the social mandate, including professional ethical guidelines and academic standards (Ministry of Education and Research Citation2005, Citation2019; Norwegian Union of Social Workers and Social Educators (FO) Citation2015). A bachelor’s degree in child welfare qualifies graduates for e.g. work in the CWS. Although other professions also work in the CWS, the majority have a bachelor’s degree in social work, including child welfare (Statistics Norway Citation2020). In line with the regulations, students must complete practice placements, field training and skills training, and at least 30 ECTS must be in direct interaction with service users.

The child welfare service in Norway

The child welfare system in Norway is family service oriented and child centric (Berrick et al. Citation2016a, Citation2019; Skivenes Citation2011; Skivenes and Søvig Citation2017). The CWS have a wide variety of duties, which include preventive work such as voluntary in-home measures but also more intrusive and compulsory measures such as out-of-home placements (The Child Welfare Act Citation1992; Skivenes and Søvig Citation2017). The majority of CWS measures are voluntary in-home measures (Statistics of Norway 2021). A survey from 2015 revealed that 80% of those who received in-home services were satisfied with the help that they had received (Christiansen Citation2015).

A characteristic feature of the Norwegian CWS has been the emphasis on the child as an independent subject of rights and in the very centre of the CWS (Skivenes and Tefre Citation2020). CWS cases start with a report of concern for a child. The threshold for opening an investigation is reason to assume that there are circumstances that may provide a basis for voluntary measures (The Child Welfare Act Citation1992; Skivenes Citation2011). The assumption is that children in need are best helped through their parents and cooperation with and respect for parents are central to the work of the CWS and embodied in the Child Welfare Act (The Child Welfare Act Citation1992). Heggen and Dahl (Citation2017) argue that the responsibilities of the CWS in Norway can be described as incompatible. This incompatibility involves the managing of two roles, that of a helper and a controller in charge of both voluntary and intrusive measures. Relational competence and the ability to establish working partnerships with service users are assumed to be especially important to deal with this dual role in emotionally demanding situations (Baugerud, Vangbæk, and Melinder Citation2018).

In addition to stressful emotional work, CWS workers also experience high time pressure and high workload (Sørensen, Skjeggestad, and Slettebø Citation2019). There is a relatively high turnover in several of the services (Røsdal et al. Citation2017; The Norwegian Union of Social Workers and Social Educators (FO) Citation2015). Researchers have pointed out that in Norway there is a gap between the welfare state’s ambitions for the CWS and the reality described by service users and practitioners (e.g. Vike, Debesay, and Haukelien Citation2016). There has been a significant focus on the quality of CWS work in Norway. Investigations and audits have revealed many errors and omissions (Skivenes and Tefre Citation2020). In recent years, Norway has been convicted in the European Court of Human Rights a number of times for violations of human rights in child welfare cases (Emberland Citation2016; Köhler-Olsen Citation2019). Part of the discussions deals with the ability of the CWS to make assessments in complex cases and the ability and willingness to cooperate with children and their parents. These discussions are important in the further development of the CWS. The legitimacy of the CWS is closely linked to how the service is perceived by the general public, service users and social institutions (Skivenes and Thoburn Citation2017). A number of measures have been implemented to raise the quality and competence of CWE and the CWS.

The knowledge base in child welfare work

The knowledge base of social work consists of several different subject areas necessary to solve complex and composite issues as a CWS worker (Grimen Citation2008; Munro Citation2019; Skau Citation2017; Smeby and Mausethagen Citation2011; Trevithick Citation2008). There are several models that seek to explain the composition of the knowledge base of social work. A common feature of these models is that theoretical and practical competence are seen as complementary and that individual personal qualities are an important part of overall professional competence. Nevertheless, there are certain challenges in trying to define and articulate the knowledge base more specifically. These challenges can be said to be related to the heterotelic purpose of CWS (Grimen Citation2008), where the tasks that professionals must solve will form a basis for how they use their overall competence. Abstract theories must be given a practical relevance and applied in combination with professional skills and personal competence, as a basis for finding good solutions in practice. Recent years have seen a greater focus on incorporating user experiences into the knowledge base. Trevithick emphasizes that critical thinking, reflexivity and relational practice surround the framework, emphasizing the significance of knowing oneself as an prerequisite for social workers, and a necessity to understand the other (Trevithick Citation2018). According to Skau (Citation2017), there is a close connection between knowing oneself and the quality of the work performed.

Previous research

A Norwegian study of CWS professionals’ use of their knowledge base showed that they largely based their work on informal knowledge such as customary practices in their offices and their own and colleagues’ experiences (Heggen and Dahl Citation2017). A Swedish study found similar trends and that knowledge from education and research was considered less relevant than informal knowledge (Dellgran and Höjer Citation2005). Thus, values and norms in the community of practice are clearly of great importance for how CWS professionals perform their work.

In education, there is also a transfer of values and attitudes that are outside the formal curriculum. Both formal and informal curricula are part of the learning environment, in addition to hidden curricula which consist of ‘the intangible moral behavior exemplified by role models’ (Ssebunnya Citation2013, 49). Hafferty (Citation1998) draws attention to how the learning environment will affect what the students learn, and thus their readiness for work. The teachers involved should therefore pay close attention to the impact of the learning environment.

Students’ recognition of their profession is assumed to impact their learning, self-understanding and practice (Sullivan and Shulman Citation2005). It is suggested that students should be encouraged to reflect on their own learning process and develop an incipient identity as a professional (Ovrum and Kapstad Citation2019; Sicora Citation2017; Vindegg and Stang Citation2016).

Motivation to choose social work is often altruistically dominated (Jensen and Fossestøl Citation2005; Stevens et al. Citation2010). A Norwegian longitudinal study of students of social work showed that the students found that their original motives were considered by the teachers to be naive and immature. The study also found that towards the end of their education, students were unsure of their professional identity and what it meant to be a good social worker (Jensen and Fossestøl Citation2005). Studies show that the transition from education to work in the field is demanding (e.g.Bates et al. Citation2010; Bruno and Dell’Aversana Citation2018; Frost, Höjer, and Campanini Citation2013; Pösö and Forsman Citation2013). A Swedish study examined how social work students perceived their education and readiness for work at graduation (Tham and Lynch Citation2014). The most important topics were the desire for more field training, more encounters with practitioners and generally more training in practical skills. The students reported that they often disliked courses that were vague or less concrete. Moreover, ‘[c]ourses at a theoretical level were often described as difficult to comprehend or apply in practice’ (Tham and Lynch Citation2020, 709). In a later study, the same researchers found similar challenges for newly qualified social workers (Tham and Lynch Citation2020). Here they highlighted the mismatch or gap between expectations and reality for newly qualified social workers in terms of opportunities for helping service users (Tham and Lynch Citation2020). Research by Joubert (Citation2020) examined the readiness for practice of social work students in England. The study revealed that the students perceived the relationship between theory and practice as somewhat unclear. The author also found that the students emphasized the role of emotion management and self-development in practical social work.

Study design

To address the research question of how the knowledge base of the child welfare professional is understood by 1st and 2nd year bachelor’s degree students in child welfare, we asked the students to write reflective papers on this topic. The study has a qualitative design, exploring students’ reflections on child welfare competence. The students’ papers were analysed using thematic analysis inspired by the model of Braun and Clarke (Citation2006).

Setting and context

This article is part of a larger study conducted in child welfare education. The overall purpose of the study was to explore the process of becoming a child welfare professional in Norway. The students in this study were all part of a pedagogical project named ‘Child Welfare Casework’ (Kapstad and Øvrum Citation2019; Ovrum and Kapstad Citation2019, Citation2021). The purpose was to make it easier for students to receive training in working with issues and dilemmas similar to those they might encounter when they have graduated and started work. In the development of cases and dilemmas and in teaching, we collaborated with different parts of the child welfare system. The students worked on several different child welfare cases where they had to perform fictitious child welfare assessments and make decisions in cases that gradually became more serious.

The students worked on these issues in groups and in the whole class, completed documentation, and participated in role play and discussions. The teachers were active participants in the building of knowledge, through communication, guidance, feedback and dialogue. The authors of this article were among the main teachers.

Sample and data collection

The data consist of 202 reflective papers written by child welfare students (). One hundred and forty students participated in this study. All participants were undergraduates from the same college in two different semesters (first and second years of the bachelor’s degree programme). One of the classes only wrote reflective papers in the last semester. Reflective papers formed part of the work requirements in both semesters. The assignment was: ‘What competence do you consider to be particularly important for the child welfare professional?’

Table 1. ~TC~

We informed all students that although the reflective papers were a course requirement, we needed their consent to use them for research. Written informed consent forms were collected. No specific requirements were set for the form, content or length of the papers and no incentives or rewards were given for consenting/participating. We anonymized the papers before analysis. The papers were originally written in Nordic languages and the translations were performed by the authors of this article.

Data, methods, and limitations

Ethical considerations

The study was reported to the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD), which is a national centre and archive for research data. As a study within the framework of higher education, not including clients or making use of sensitive personal information, the research project was not considered to be subject to notification and thus did not need approval from the NSD.

Data analysis

Drawing on a qualitative approach, we were interested in understanding the content meaning of the students` papers (Malterud Citation2002) and pursuing interesting themes across the material (Brinkmann and Tanggaard Citation2015). Thematic analysis is especially appropriate in this respect, being a hermeneutic process that allows for flexibility in the approach to the material. We analysed the reflective papers with inspiration from the model presented by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006). The analysis was performed in NVivo and consisted of several steps as described below.

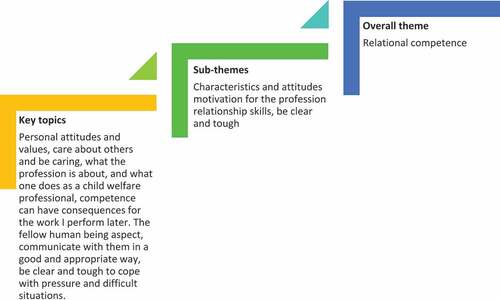

According to Braun and Clarke (Citation2006), the first step in the analysis is to gain an overview of the material as a whole. We started the analysis by reading the material separately and then sat down together to identify key topics in each text. The key topics were then sorted into preliminary sub-themes. The next step, according to Braun and Clarke (Citation2006), is to form an overall thematic grouping of the sub-themes. This process is illustrated in .

We were initially interested in looking for differences between first-year students and second-year students. However, we did not find that the content or focus of the papers changed significantly between the two groups.

Methodological considerations and limitations

Different aspects were addressed to evaluate the quality of the study. Both authors worked on the analysis together and separately. The authors have also presented preliminary findings to the research team to discuss possible ways of understanding the material.

The final thematic categories are represented by quotes from the texts. These quotes are descriptive of the main content of the categories and are representative of the overall material. Systematic analytical work and comprehensive descriptions of the material are considered to strengthen the quality of qualitative methods (Tracy Citation2010).

We were available to the students throughout both semesters. Our active participation in the students’ learning environment might have influenced how the students responded to the work requirement, thus posing a risk of material bias, either positive or negative. This close relationship may also have affected how we as researchers read and interpreted the material (Alvesson and Sköldberg Citation2009). While it may have enabled us to better understand and detect correlations in the material, it may also have prevented us from detecting nuances that could be more evident if the distance to the material and the environment were greater (Coffey and Atkinson Citation1996).

Results

In the following we will describe the three main categories that emerged through the analysis. These are 1) theoretical competence, 2) assessment and the decision-making process, and 3) relational competence. All students included several areas of competence in their papers. Nevertheless, most students concluded that relational competence was the most important. There is a clear predominance of texts where students focus on their own ability to create a good relationship with service users. One student described it as follows:

I think personal competence is very important when meeting with clients, that they feel understood and recognized. And that we have good attitudes and the knowledge needed to do a good job. I think the young people from the Change FactoryFootnote1 say it so well: “Theory, subjects and experiences can be put in a backpack, but the most important thing is that the child welfare worker has expertise in meeting children and young people with her heart first”.

This quote indicates how the students emphasized relational competence as the most important skill in child welfare work. The students in our material felt that their knowledge and skills should be used in interaction with service users. They stated that it is important that theory does not get in the way of the ‘real’ relationships, which can be understood as a tension between theory and practice in the students’ professional understanding.

Theoretical knowledge

When describing theoretical knowledge, the students addressed different topics and key concepts included in the curriculum. These were both basic theories and factual knowledge including research. We will refer to this as theory and theoretical knowledge. The findings in this study concur with those of other studies that have shown that it can be difficult to articulate and describe the knowledge base in social work (Fossestøl Citation2018; Skau Citation2017; Trevithick Citation2008, Citation2018).

The descriptions the students gave of theoretical knowledge were brief and cursory. They gave little additional explanation as to why this competence is considered particularly important or how it can be used. For example, many of them pointed out that it is essential to work within the framework of the law, but they did not explain what knowledge is needed to do this and they did not mention why this is important. Knowledge about children’s development was often mentioned, but without it being linked to a specific theory or theoretical approach. The following quote demonstrates that theoretical knowledge was identified as important but difficult to articulate:

I consider competence about the child’s development, culture and cultural sensitivity, relationship and interaction to be important. It is also important to have knowledge of different theories, what role you as a social worker have. It is important to have knowledge about drugs and psychiatry, the legislation and how it works.

Assessment and the decision-making process

The reflective papers also contain reflections on the considerable responsibility of the child welfare professional and highlight the importance of being able to make decisions based on good judgement. Several wrote about the importance of making ‘good assessments’ and ‘making the right decisions’. The students emphasized the importance of a holistic approach towards children and families. They linked assessment and decision-making processes closely to working relationally and the ability to have a good relationship with service users. When elaborating on a holistic approach and professional judgment, students continued to focus on the relational aspects. One student stated:

I consider it particularly important that a child welfare professional is able to understand the needs of each individual child and family, and does not see everyone in the same way. Being culturally sensitive, curious and open minded. One must have the desire and ability to create a relationship; one must build trust, be honest, and especially cope with hearing people’s stories.

Another student noted

To see the children and the family in their context, that I am able to assess the parents’ caring skills, I am able to communicate with the child, I am able to cooperate, I am able to handle conflict in a professional way.

To exercise professional power is also a skill that students highlighted. In the students’ texts, distribution of power is about not abusing their professional authority. The students linked the concept of power to the opportunity they have as social workers to work with families and are concerned about empowering service users. One student wrote:

We know in ourselves that we have power TO and not power OVER. We will work TOGETHER WITH families who are in contact with child welfare services. This is a demand the service users have, and an important tool for us in the process of building trust (student’s own emphasis).

It is interesting that the students linked the exercise of professional power to relational competence. Only to a small extent did they write about power as a necessary part of their professional authority and the dilemmas this may represent. Thus, dilemmas and conflicts were downplayed, giving the impression that collaboration with service users largely offsets the asymmetric power relationship.

Relational competence

To convey empathy and understanding is an important part of the relational competence, as described by the students. The students seek to empower the service users to make changes in their lives. According to our data, relational competence and the ability to establish a working partnership with both parents and the children are key issues in social work.

I consider relational competence and personal competence to be particularly important for the child welfare worker. I believe that without some kind of basic relationship, it is not possible to do satisfactory social work. Adequate yes, but not fully satisfactory. The word social work covers this well: social work. Social is about community and community is about relations.

To study child welfare is to take a stance on helping vulnerable children and adolescents. The choice of education must be based on this desire. Self-knowledge and empathy are crucial, according to the students.

Knowing your own boundaries and what baggage you carry yourself implies that impulsive emotions and reactions have already been processed and will not affect as much as if you were not aware of this.

In this respect, the students were also concerned about how their investment in their education could promote or inhibit their prospects of doing well as a child welfare professional and thus affecting the lives of others.

The students sought to empower children by listening to them and giving them support to enable them to trust the professional and express their needs and opinions. The students stated that the child and the child`s best interest must be the main focus in CWS. This focus is considered decisive for whether children and adolescents are able to express their views and needs, and thus decisive for bringing about change in their lives. The students pointed out that it is therefore important to be a professional who shows emotions and is genuine in relating to children.

Taken as a whole, the descriptions of relational competencies correlate with a therapeutic understanding of social work (Skivenes Citation2011; Trevithick Citation2003), emphasizing being a caring professional (Baugerud, Vangbæk, and Melinder Citation2018) and highlighting relational work as a foundation for change and development (Howe Citation1998; Skau Citation2017; Trevithick Citation2018).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to gain insight into how child welfare students perceive the main competence of their profession. The students were asked, ‘What competence do you consider to be particularly important for the child welfare professional?’ i.e. a question that invites reflection on the child welfare knowledge base and its practical implications. The analysis shows that relational competence was considered the most important competence and was elaborated on the most by students. In the other two areas of competence, little detail was provided and there were few explanations as to how and why these competences are useful.

The analysis leads to the question of whether relational competence is too prominent in the students’ understanding of their profession’s knowledge base and thus their professional identity. In addition, it leads to the question of how the educators can monitor and initiate development of professional competence.

CWS competence and the use of self

The students in our study highlight relational competence as particularly important. The fact that CWS workers convey empathy and understanding in encounters with service users is an important part of the relationship work as described by the students. Empathy, acceptance and recognition of the other are central to working with service users in need and are considered key elements in achieving good results in social work (Howe Citation2008). To be able to express empathy and knowing oneself are important skills (Ferguson Citation2018; Howe Citation2008; Ingram Citation2013). Being able to tune in to the other and handle various emotional transactions is a key element in relational work (Baugerud, Vangbæk, and Melinder Citation2018; Ferguson Citation2018). Relationally competent professionals are called for by service users, both parents and children (Ferguson Citation2005; Munro Citation2019; National Association of Social Workers Citation2017). The students’ reflections as they appear in this study are in line with this.

The students also highlighted several theoretical concepts, research and factual knowledge that are central to child welfare. They only touched on the core concepts, and because these were not elaborated, they appear to be general and without context.

There are few in-depth descriptions of these concepts and what significance they should have in practical work. Very few students wrote about how theoretical knowledge will influence their work, and thus paid little attention to the challenge of one’s perspective largely determining what one sees and how one understands and interprets different situations.

Reflections on how the different concepts can be applied in practice are scarce in the students’ texts. These basic findings are supported by research showing that it can be difficult for students to understand the practical significance of abstract theories (Fossestøl Citation2018; Jensen and Fossestøl Citation2005; Skau Citation2017; Tham and Lynch Citation2014). This can have an impact on the students’ motivation to immerse themselves in theoretical topics during their education. Challenges related to articulating the subject matter can make students choose to focus on other parts of the knowledge base. This can have a negative effect on their understanding of the relevance of theoretical knowledge. When students write about the importance of assessment and the decision-making process, this is related to CWS work. In CWS casework the professional must identify needs and risks, evaluate, and make professional judgements related to interventions. One might have expected students to apply theoretical knowledge to a greater extent, since this is a central part of the learning outcome as described in the course and the national regulation (Ministry of Education and Research Citation2019). Nevertheless, the conflict between theory and practice is a well-known challenge.

Studies have shown that it is challenging to articulate how theoretical knowledge is applied in casework, even for experienced practitioners. This is problematic because assessments and decisions are expected to be documented and professionally justified.

The students’ descriptions of competence indicate an understanding of the relational aspect of the work as most important and the professional role as mainly that of a relational actor. Our findings may suggest that students find it easier to comprehend how and why relational competence can be applied in practice. The students were concerned about how ‘knowing oneself’ would affect their work and their ability to establish good working partnerships with service users.

A closer examination of the students’ reflections reveals a picture of the good child welfare professional who is able to establish relationships and enter into collaboration to enable service users to receive the help they need. The good child welfare professional relates to service users in a way that enhances their strengths and allows them to use these strengths in their lives. The students take on great personal responsibility to be able to realize what they perceive to be the expectations of the profession. The analysis indicates that they imagine that establishing good relationships with service users will even out asymmetric power relations and bridge conflicts of interest. In these descriptions, the child welfare professional’s theoretical competence and decision-making role are downplayed.

Students’ perceptions and the transition to CWS work

The self-construction of the child welfare professional as a relational actor is in line with social work values. Nevertheless, it might conflict with known challenges in the field (Berrick et al. Citation2016b; Ferguson Citation2017; Kojan and Christiansen Citation2016; Munro Citation2019). These challenges can put pressure on the professional’s ability to perform good relational work (Berrick et al. Citation2016b; Ferguson Citation2017; Kojan and Christiansen Citation2016; Munro Citation2019).

Many service users are ‘involuntary clients’ (Ellett et al. Citation2007) and do not want to be in contact with the CWS. Contact with the CWS is by some seen as a threat to their family and its existence (Ferguson Citation2017, Citation2018). Thus, the CWS must be able to balance these challenging and incompatible roles (Heggen and Dahl Citation2017), and the spectrum of voluntary and compulsory measures (Pösö et al. Citation2018).

The students’ construction of the child welfare professional being able to bridge this gap contrasts with these challenges, and downplays the dilemmas and conflicts of interest CWS work often represents. In a CWS perspective this can be understood as the ‘rule of optimism’ (Dingwall, Eekelaar, and Murray Citation2014), where an over-identification with parents may mean that the professional does not deal with the difficult circumstances present in the family (Ferguson Citation2017; NOU Citation2017:12 2017).

Implications for child welfare education

In Norway as well as internationally, it is known that the transition from education to work in CWS is demanding (Bates et al. Citation2010; Munro Citation2019; Pösö and Forsman Citation2013; Tham and Lynch Citation2014; The Norwegian Union of Social Workers and Social Educators (FO) Citation2015). Research indicates that there is a mismatch in expectation and reality when it comes to the opportunity for helping service-users (Tham and Lynch Citation2020).

CWE aims to facilitate students’ learning and prepare them for their future profession. However, it can be challenging to facilitate teaching and learning that will accommodate the complexity of CWS and provide a deeper understanding of what such work requires. Planning the program will constantly involve priorities regarding content and teaching methodology. It is therefore important to monitor students’ development and assess how far the learning environment contributes to this. As described by Sullivan and Shulman (Citation2005), fundamental to developing a professional identity is the students’ learning environment during their education. The learning environment consists of both academic aspects and social learning that takes place in interaction with others in the same programme and the same profession. It is also marked by the organizational, social and cultural context that encompasses both education and CWS (Benbenishty et al. Citation2015; Munro Citation2019). The findings in this article call for a closer examination of the context surrounding the education, and of which areas of knowledge and values are emphasized in the learning environment through the explicit, implicit, and hidden curriculum (Bogo and Wayne Citation2013). For example, since the students in our study highlight relational work as the most important competence, we wish to point out two factors that CWE should take into account. Firstly, one implication may be that teachers on the program need to focus more on the emotional curriculum (Grant Citation2014; Grant and Kinman Citation2012) to enhance students’ self-knowledge. Developing emotional intelligence and resilience (Ferguson Citation2005; Ingram Citation2013) is important to set personal and professional boundaries. This can also serve as a protective measure to cope with working with people in crisis where anxiety, anger and despair unfold. To ease the transition from education to practice, it will be essential to teach students the importance of not assuming personal responsibility for what lies outside their mandate in CWS, enabling them to handle emotional strains and channel empathy in an appropriate way (Grant Citation2014; Grant and Kinman Citation2012; Grant, Kinman, and Alexander Citation2014). Secondly, CWS involves the exercise of statutory power, and it will therefore be important for the program to include an understanding of the dilemmas and asymmetric power present in CWS. As novices, students will need to simplify the complex reality, and then the unpleasantness of professional power can be difficult to put into words. If the program is unsuccessful in integrating this as part of the overall professional competence, it could present challenges for the student’s transition to work.

Concluding remarks

Insight into students’ understanding and ability to articulate their knowledge base is important in order to enhance quality in education. Knowledge integration is challenging and is particularly relevant in programs based on such a broad knowledge base as child welfare education is. In addition, it is a profession that is constantly discussed, challenged and criticized in the public sphere.

There is a lot at stake in CWS work, and the desire to create change and good outcomes is considerable. The desire to help and support children and families is noble, and to impede this is reprehensible. It is almost a moral betrayal when the system falls short. In this study, we have shown that child welfare students are prepared to take on considerable responsibility in order to create good outcomes for children and families.

Insights into what constitutes student assumptions and constructions of their knowledge base can make an important contribution as improvements in child welfare education and the transition to work.

Limitations

This is a qualitative study that does not claim generalizability beyond the specific context in which this research took place. The aim of this study was to capture the reflections from students in two classes in a child welfare program. Including reflections from other relevant agents such as university teachers and representatives from the child welfare and child protection field, newly qualified CWS professionals and even collecting reflective papers from students at other universities would broaden the perspective. However, the insights presented might serve as an opportunity to elicit students’ reflections on an important aspect of education. Readers should consider this and use their professional expertise when considering the relevance and possible implications for their particular situation/context.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our peer reviewers for their essential and constructive feedback. Their comments have been valuable in the preparation of the manuscript.

Many thanks to all the students who participated in this study. Your reflections have provided valuable knowledge. We also wish to thank Professor Halvard Vike for insightful input and discussion on the preliminary findings and manuscript. In addition, we would like to thank the members of the PhD seminar in the Department of Health, Social and Welfare Studies at the University of South-Eastern Norway for comments on the preliminary findings.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. (Forandringsfabrikken Citation2020)

References

- Adams, K., S. Hean, P. Sturgis, and J. M. Clark. 2006. “Investigating the Factors Influencing Professional Identity of First‐year Health and Social Care Students.” Learning in Health and Social Care 5 (2): 55–68. doi:10.1111/j.1473-6861.2006.00119.x.

- Alvesson, M., and K. Sköldberg. 2009. Reflexive Methodology: New Vistas for Qualitative Research. 2nd ed. London: Sage.

- Bates, N., T. Immins, J. Parker, S. Keen, L. Rutter, K. Brown, and S. Zsigo. 2010. “‘Baptism of Fire’: The First Year in the Life of a Newly Qualified Social Worker.” Social Work Education 29 (2): 152–170. doi:10.1080/02615470902856697.

- Baugerud, G. A., S. Vangbæk, and A. Melinder. 2018. “Secondary Traumatic Stress, Burnout and Compassion Satisfaction among Norwegian Child Protection Workers: Protective and Risk Factors.” The British Journal of Social Work 48 (1): 215–235. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcx002.

- Benbenishty, R., B. Davidson-Arad, M. López, J. Devaney, T. Spratt, C. Koopmans, E. J. Knorth, C. L. M. Witteman, J. F. Del Valle, and D. Hayes. 2015. “Decision Making in Child Protection: An International Comparative Study on Maltreatment Substantiation, Risk Assessment and Interventions Recommendations, and the Role of Professionals’ Child Welfare Attitudes.” Child Abuse & Neglect 49: 63–75. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.03.015.

- Berrick, J., J. Dickens, T. Pösö, and M. Skivenes. 2016a. “Corrigendum to “Children’s Involvement in Care Order Decision-making: A Cross Country Analysis” Child Abuse & Neglect 49 (2015) 128–141.” Child Abuse & Neglect 60: 77. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.10.002.

- Berrick, J., J. Dickens, T. Pösö, and M. Skivenes. 2016b. “Time, Institutional Support, and Quality of Decision Making in Child Protection: A Cross-Country Analysis.” Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance 40 (5): 451–468. doi:10.1080/23303131.2016.1159637.

- Berrick, J., J. Dickens, T. Pösö, and M. Skivenes. 2019. “Children’s and Parents’ Involvement in Care Order Proceedings: A Cross-national Comparison of Judicial Decision-makers’ Views and Experiences.” Journal of Social Welfare and Family Law 41 (2): 188–204. doi:10.1080/09649069.2019.1590902.

- Bogo, M., and J. Wayne. 2013. “The Implicit Curriculum in Social Work Education: The Culture of Human Interchange.” Journal of Teaching in Social Work 33 (1): 2–14. doi:10.1080/08841233.2012.746951.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Brinkmann, S., and L. Tanggaard. 2015. Kvalitative metoder: En grundbog. 2nd ed. Copenhaven: Hans Reitzel.

- Bruno, A., and G. Dell’Aversana. 2018. “‘What Shall I Pack in My Suitcase?’: The Role of Work-integrated Learning in Sustaining Social Work Students’ Professional Identity.” Social Work Education 37 (1): 34–48. doi:10.1080/02615479.2017.1363883.

- Christiansen, Ø. 2015. Hjelpetiltak i barnevernet - en kunnskapsstatus. Uni Research, Regional Centre for Child and Youth Mental Helath and Child Welfare. Retrieved from https://bufdir.no/globalassets/global/kunnskapsstatus_hjelpetiltak_i_barnevernet.pdf

- Coffey, A., and P. Atkinson. 1996. Making Sense of Qualitative Data: Complementary Research Strategies. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Dellgran, P., and S. Höjer. 2005. “Privatisation as Professionalisation? Attitudes, Motives and Achievements among Swedish Social Workers.” European Journal of Social Work 8 (1): 39–62. doi:10.1080/1369145042000331369.

- Dingwall, R., J. Eekelaar, and T. Murray. 2014. The Protection of Children. State Intervention and Family Life. 2 ed. London: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Ellett, A. J., J. I. Ellis, T. M. Westbrook, and D. Dews. 2007. “A Qualitative Study of 369 Child Welfare Professionals’ Perspectives about Factors Contributing to Employee Retention and Turnover.” Children and Youth Services Review 29 (2): 264–281. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2006.07.005.

- Emberland, M. 2016. “Det norske barnevernet under lupen.” LoR 55 (6): 329–330. doi:10.18261/.1504-3061-2016-06-01.

- Ferguson, H. 2005. “Working with Violence, the Emotions and the Psycho-social Dynamics of Child Protection: Reflections on the Victoria Climbié Case.” Social Work Education 24 (7): 781–795. doi:10.1080/02615470500238702.

- Ferguson, H. 2017. “How Children Become Invisible in Child Protection Work: Findings from Research into Day-to-Day Social Work Practice.” British Journal of Social Work 47 (4): 1007–1023. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcw065.

- Ferguson, H. 2018. “How Social Workers Reflect in Action and When and Why They Don’t: The Possibilities and Limits to Reflective Practice in Social Work.” Social Work Education 37 (4): 415–427. doi:10.1080/02615479.2017.1413083.

- Forandringsfabrikken. (2020). “Om Forandringsfabrikken.” Retrieved from https://forandringsfabrikken.no/om-ff?fbclid=IwAR2rUSrv8oyKQzYwkE3SiYxIK1pHh8cugwyZPsyXKm-qmWl1NzJXCIL3g0U

- Fossestøl, B. 2018. “Ethics, Knowledge and Ambivalence in Social Workers’ Professional Self-Understanding.” The British Journal of Social Work. doi:10.1093/social/bcy113.

- Frost, E., S. Höjer, and A. Campanini. 2013. “Readiness for Practice: Social Work Students’ Perspectives in England, Italy, and Sweden.” European Journal of Social Work 16 (3): 327–343. doi:10.1080/13691457.2012.716397.

- Grant, L. 2014. “Hearts and Minds: Aspects of Empathy and Wellbeing in Social Work Students.” Social Work Education 33 (3): 338–352. doi:10.1080/02615479.2013.805191.

- Grant, L., and G. Kinman. 2012. “Enhancing Wellbeing in Social Work Students: Building Resilience in the Next Generation.” Social Work Education 31 (5): 605–621. doi:10.1080/02615479.2011.590931.

- Grant, L., G. Kinman, and K. Alexander. 2014. “What’s All This Talk about Emotion? Developing Emotional Intelligence in Social Work Students.” Social Work Education 33 (7): 874–889. doi:10.1080/02615479.2014.891012.

- Grimen, H. 2008. “Profesjon og kunnskap.” In Profesjonsstudier, edited by A. Molander and L. I. Terum, 71–86. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Hafferty, F. W. 1998. “Beyond Curriculum Reform: Confronting Medicine’s Hidden Curriculum.” Acad Med 73 (4): 403–407. doi:10.1097/00001888-199804000-00013.

- Heggen, K., and S. Dahl. 2017. “Barnevernets kunnskapsgrunnlag.” Fontene Forskning 10: 70–83.

- Howe, D. 1998. “Relationship-based Thinking and Practice in Social Work.” Journal of Social Work Practice 12 (1): 45–56. doi:10.1080/02650539808415131.

- Howe, D. 2008. The Emotionally Intelligent Social Worker. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillian.

- Ingram, R. 2013. “Emotions, Social Work Practice and Supervision: An Uneasy Alliance?” Journal of Social Work Practice 27 (1): 5–19. doi:10.1080/02650533.2012.745842.

- Jensen, K., and B. Fossestøl. 2005. “Et språk for de gode gjerninger? Om sosialarbeiderstudenter og deres motivasjon.” Nordisk sosialt arbeid 25 (1): 17–30. doi:10.18261/1504-3037-2005-01-03.

- Joubert, M. 2020. “Social Work Students’ Perceptions of Their Readiness for Practice and to Practise.” Social Work Education 1–24. doi:10.1080/02615479.2020.1749587.

- Kapstad, S. M., and I. T. Øvrum. 2019. “Om hvordan kunnskap og ferdigheter kan bli gode løsninger i praksis.” In Barnevernspedagogen - nær og profesjonell, edited by M. Paulsen, 22–30. Oslo: Fellesorganisasjonen.

- Köhler-Olsen, J. 2019. “EMD: Strand Lobben med flere mot Norge.” Tidsskrift for velferdsforskning 22 (4): 341–346. doi:10.18261/.2464-3076-2019-04-07.

- Kojan, B. H., and Ø. Christiansen. 2016. “Å fatte beslutninger i barnevernet.” In Beslutninger i barnevernet, edited by Ø. Christiansen and B. H. Kojan, 19–33. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Lwin, K., B. Fallon, N. Trocmé, J. Fluke, and F. Mishna. 2018. “A Changing Child Welfare Workforce: What Worker Characteristics are Valued in Child Welfare?” Child Abuse & Neglect 81: 170–180. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.04.029.

- Malterud, K. 2002. “Kvalitative metoder i medisinsk forskning - forutsetninger, muligheter og begrensninger.” Tidsskrift for Den norske lægeforening 122 (25): 2468–2472.

- Ministry of Education and Research. (2005). National Regulations Relating to a Common Curriculum for Health and Social Care Education. Oslo Retrieved from https://lovdata.no/dokument/SF/forskrift/2017-09-06-1353?q=forskrift%20barnevernspedagogutdanningmin

- Ministry of Education and Research. (2019). Regulations on National Guidelines for Bachelor in Child Protection and Child Welfare. Oslo Retrieved from https://lovdata.no/dokument/SF/forskrift/2019-03-15-398/

- Munro, E. 2019. Effective Child Protection. London: Sage.

- National Association of Social Workers. (2017). “Code of Ethics.” Retrieved from https://www.socialworkers.org/About/Ethics/Code-of-Ethics/Code-of-Ethics-English

- Norwegian Union of Social Workers and Social Educators (FO). (2015). “Yrkesetisk grunnlagsdokument for barnevernpedagoger, sosionomer, vernepleiere og velferdsvitere: Stå opp for trygghet.” In Norwegian Union of Social Workers and Social Educators (FO) 3–14

- NOU 2017:12. 2017. “Svikt og svik — Gjennomgang av saker hvor barn har vært utsatt for vold, seksuelle overgrep og omsorgssvikt.” Ministry of Children and Equality. Oslo. Retrieved from. https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/3be8090f3c354f5eb821535142071c50/horingsnotat-l595756.pdf

- NSD, N. C. f. R. D. Retrieved from https://www.nsd.no/

- Oterholm, I. 2016. “Kompetanse til arbeid i barneverntjenesten – Ulike aktørers synspunkter.” Tidsskriftet Norges Barnevern 93 (3–04): 146–164. doi:10.18261/.1891-1838-2016-03-04-02ER.

- Ovrum, I. T., and S. M. Kapstad. 2019. “Hvordan kan barnevernfaglig undersøkelsesarbeid læres?” Tidsskriftet Norges Barnevern 96 (3): 190–204. doi:10.18261/.1891-1838-2019-03-05.

- Ovrum, I. T., and S. M. Kapstad. 2021. “Universitetslæreres erfaringer med digitalisering i et pedagogisk utviklingsprosjekt.” Uniped 44 (4): 226–238. doi:10.18261/.1893-8981-2021-04-02ER.

- Pösö, T., and S. Forsman. 2013. “Messages to Social Work Education: What Makes Social Workers Continue and Cope in Child Welfare?” Social Work Education 32 (5): 650–661. doi:10.1080/02615479.2012.694417.

- Pösö, T., E. Pekkarinen, S. Helavirta, and R. Laakso. 2018. “‘Voluntary’ and ‘Involuntary’ Child Welfare: Challenging the Distinction.” Journal of Social Work 18 (3): 253–272. doi:10.1177/1468017316653269.

- Røsdal, T., K. Nesje, P. O. Aamodt, E. H. Larsen, and S. M. Tellmann. 2017. “Kompetanse i den kommunale barnevernstjenesten: Kompetansekartlegging og gjennomgang av relevante utdanninger.” Nordisk institutt for studier av innovasjon, forskning og utdanning (NIFU) 2017 (28) 3–330 .

- Sicora, A. 2017. “Reflective Practice, Risk and Mistakes in Social Work.” Journal of Social Work Practice 31 (4): 491–502. doi:10.1080/02650533.2017.1394823.

- Skau, G. M. 2017. Gode fagfolk vokser: Personlig kompetanse i arbeid med mennesker. 5. th. ed. Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

- Skivenes, M. 2011. “Norway, Toward A Child-Centric Perspective.” In Child Protection Systems, International Trends and Orientations, edited by N. Gilbert, N. Parton, and M. Skivenes, 154–179. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Skivenes, M., and K. H. Søvig. 2017. “Norway: Child Welfare Decision-making in Cases of Removals of Children.” In Child Welfare Removals by the State. A Cross-country Analysis of Decision-making Systems, edited by K. Burns, T. Pösö, and M. Skivenes, 40–65. New Yotk: Oxford University Press.

- Skivenes, M., and Ø. Tefre. 2020. “Errors and Mistakes in the Norwegian Child Protection System.” In Errors and Mistakes in Child Protection: International Discourses, Approaches and Strategies, edited by K. Biesel, J. Masson, N. Parton, and T. Pösö, 115–134. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Skivenes, M., and J. Thoburn. 2017. “Citizens’ Views in Four Jurisdictions on Placement Policies for Maltreated Children.” Child & Family Social Work 22 (4): 1472–1479. doi:10.1111/cfs.12369.

- Skivenes, M., and M. Tonheim. 2016. “Improving the Care Order Decision-Making Processes: Viewpoints of Child Welfare Workers in Four Countries.” Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance 40 (2): 107–117. doi:10.1080/23303131.2015.1123789.

- Smeby, J. C., and S. Mausethagen. 2011. Kvalifisering til “velferdsstatens yrker”. Retrieved from Oslo: Statistics of Norway 149–169 .

- Sørensen, T., E. Skjeggestad, and T. Slettebø. 2019. Faglig forsvarlighet i barnevernet: En kvantitativ undersøkelse av forsvarlighet, internkontroll, avvik og arbeidskultur i den kommunale barnevernstjenesten. Oslo: Vitenskapelige Høgskole.

- Ssebunnya, G. 2013. “Beyond the Hidden Curriculum: The Challenging Search for Authentic Values in Medical Ethics Education.” South African Journal of Bioethics and Law 6: 48–51. doi:10.7196/sajbl.267.

- Statistics Norway. (2020). “4 av 5 i det kommunale barnevernet har høyere utdanning.” Retrieved from https://www.ssb.no/sosiale-forhold-og-kriminalitet/artikler-og-publikasjoner/4-av-5-i-det-kommunale-barnevernet-har-hoyere-utdanning

- Stevens, M., J. Moriarty, J. Manthorpe, S. Hussein, E. Sharpe, J. Orme, … B. R. Crisp. 2010. “Helping Others or a Rewarding Career? Investigating Student Motivations to Train as Social Workers in England.” Journal of Social Work 12 (1): 16–36. doi:10.1177/1468017310380085.

- Sullivan, W. M., and L. S. Shulman. 2005. Work and Integrity: The Crisis and Promise of Professionalism in America. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- The Child Welfare Act, (1992).

- The Norwegian Directorate for Children, Y. a. F. A. 2019. “Utredning av kompetansehevingstiltak i barnevernet.” Retrieved from. https://bufdir.no/nn/Bibliotek/Dokumentside/?docId=BUF00005020

- Tham, P., and D. Lynch. 2014. “Prepared for Practice? Graduating Social Work Students’ Reflections on Their Education, Competence and Skills.” Social Work Education 33 (6): 704–717. doi:10.1080/02615479.2014.881468.

- Tham, P., and D. Lynch. 2020. “‘Perhaps I Should Be Working with Potted Plants or Standing at the Fish Counter Instead?’: Newly Educated Social Workers’ Reflections on Their First Years in Practice.” European Journal of Social Work 1–13. doi:10.1080/13691457.2020.1760793.

- Tracy, S. J. 2010. “Qualitative Quality: Eight “Big-tent” Criteria for Excellent Qualitative Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 16 (10): 837–851. doi:10.1177/1077800410383121.

- Trevithick, P. 2003. “Effective Relationship-based Practice: A Theoretical Exploration.” Journal of Social Work Practice 17 (2): 163–176. doi:10.1080/026505302000145699.

- Trevithick, P. 2008. “Revisiting the Knowledge Base of Social Work: A Framework for Practice.” British Journal of Social Work 38 (6): 1212–1237. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcm026.

- Trevithick, P. 2018. “The ‘Self’ and ‘Use of Self’ in Social Work: A Contribution to the Development of A Coherent Theoretical Framework.” The British Journal of Social Work 48 (7): 1836–1854. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcx133.

- Vike, H., J. Debesay, and H. Haukelien. 2016. “Betingelser for profesjonsutøvelse i en velferdsstat i endring.” In Tilbakeblikk på velferdsstaten: Politikk, styring og tjenester, edited by H. Vike, J. Debesay, and H. Haukelien, 14–39. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk.

- Vindegg, J., and E. G. Stang. 2016. “Utvikling av kritisk refleksjon i barnevernet gjennom evaluering og selvregulering.” Tidsskriftet Norges Barnevern 93 (3–04): 200–212. doi:10.18261/.1891-1838-2016-03-04-05ER.