ABSTRACT

This paper contributes to the research field of interprofessional education by reporting on an ongoing collaboration between a Social Work Study Programme and two Public Service Interpreting programs located at three universities in Sweden. The article explores the question of what is required to establish a sustainable curriculum for interprofessional education to prepare social work and interpreting students to manage interpreter-mediated social work encounters. Based on experiences made from six IPE sessions over the past three years, two important perspectives are identified and discussed. Firstly, is the pedagogical perspective, where the IPE seen as a situated learning activity, offering a learning space in which awareness of communicative skills such as the organization of turns and division of labour in interpreter-mediated social work encounters are made visible, practiced and reflected upon. The communicative skills relate both to professional and interprofessional expectations and duties of these groups of students. Secondly, is the organizational perspective, where the IPE is regarded as an example of educational collaboration. At a general overall level, the crucial aspects identified for establishing a sustainable IPE are the actual needs-basis, persistence over time and small-scaleness of the development process. The online format, close collaboration between the interpreting programs and the specific IPE team are other crucial aspects identified in the organization of this collaborative venture. The feedback from students have so far been very positive and with an IPE in place, there are now good opportunities to develop these training sessions in different directions and systematically assess the IPE.

Introduction

High demands are placed on public servants when it comes to managing professional encounters with clients from different linguistic and cultural backgrounds. This is very much the case for social work encounters taking place in linguistically diverse contexts. Social work encounters are often described as complex due to the context and the sensitivity of issues dealt with. A characteristic feature of social work encounter is the efforts to achieve a collaborative communicative format in order to enable client participation. As such, one of the core purposes of social workers is understanding ‘the person within the context of his or her particular situation’ (Buzungu Citation2023, 4–5) which requires trust between social workers and clients in order for the latter to share thoughts and ideas about their situation. The collaborativeness helps social workers to ‘see, hear, and understand, and that clients, in turn, experience recognition through being seen, heard, and understood’ (Buzungu Citation2023, 8). Communication, therefore, is not only an important part of social work, it often is the very essence of work as it is through talk that empowerment, challenging, information and guiding is performed in these encounters.

Encounters in which the social workers and clients do not share a common language of communication may present substantial barriers to participation (Piller Citation2016). One way to improve client participation in these encounters is to rely on interpreter-mediation. Including an interpreter adds a layer of communicative complexity to the already complex professional practice of social workers. Interpreter-mediated conversations differ from monolingual ones as conversational turns follow a radically different organization. The interpreter is usually expected to deliver an oral translation after each utterance and the constant shifting of turns with the interpreter affects the rhythm of the talk considerably. Apart from advanced bilingual skills, interpreters need specific professional skills in, for example, interpreting techniques and attention management control. As such, high professional standards for interpreters is required not only for high quality interpreting, but also to secure participation since ‘the participation of minority language speakers in these meetings largely depends on the skills and competence of the interpreter’ (Buzungu Citation2023, 63). From the social workers’ perspectives, high standards refer to awareness of the communicative peculiarities of interpreter-mediated conversation, but also an overall understanding of ‘the client’s position as a rights holder, formal and legal certainty, as well as their own possibilities to fulfill their duties’ (Gustafsson, Norström, and Åberg Citation2022). This means that social workers and interpreters, apart from their own professional skills, also need to be aware of each other’s different roles in interpreter-mediated encounters and the ability to collaborate interprofessionally (Krystallidou Citation2022). Not managing professional and interprofessional aspects of interpreter-mediated encounters may lead to misunderstandings and loss of trust and respect between the social workers and clients, which hampers participation (Buzungu Citation2023; Tipton and Furmanek Citation2016; Wadensjö Citation1998; Westlake and Jones Citation2018).

The question of how to prepare future public servants and interpreters for working life and interprofessional collaboration has triggered pedagogical activities of various kinds for students within educational programs (Chouc and Maria Conde Citation2016; Crezee and Marianacci Citation2022; González-Davies and Enríquez-Raído Citation2016). This article focuses on a specific pedagogical activity called Interprofessional Education (IPE). Interprofessional education refers to joint training sessions between students from different educational programs, who come together to learn about, from and with each other (WHO Citation2010). This far only a few studies have examined the specific use of IPE in social work and interpreting programs and there is a call for further systematic studies in the literature (Hlavac and Saunders Citation2021a, Citation2021b; Krystallidou Citation2022; Tipton and Furmanek Citation2016; Westlake and Jones Citation2018). This article responds to that call by reporting on an ongoing IPE collaboration between two educational programs in Sweden: the Social Work Study Programme at Linnaeus University, and two Public Service Interpreting (PSI) programs, one at Stockholm University and the other at Lund University.

This discursive and reflective article is centred around the following question: ‘What is required to establish a sustainable curriculum for interprofessional education to prepare social work and interpreting students to manage interpreter-mediated social work encounters?’ Being the first initiative of its kind in Sweden involving soon-to-be social workers and interpreters, experiences made during the process of designing and developing the current IPE are shared. The IPE is discussed as a pedagogical learning activity and an example of educational collaboration across faculties and universities. The setting and participants of the current IPE are described and a structured account for the implementation of the IPE sessions is given. The article is concluded with a discussion from a pedagogical perspective on the experiences made preparing prospective public servants and interpreters, as well as from an organizational perspective as an example of cross-faculty educational collaboration. Both these perspectives need to be taken into consideration in the establishment of a sustainable IPE curriculum.

Interprofessional education as a learning activity

Interprofessional education has been used in healthcare by practitioners and students for the past 30 years, evolving into a structured and theory-informed learning activity for different healthcare professionals (Andersson, Smith, and Hammick Citation2016; Black et al. Citation2022). The setting of IPE is structured and supervised, offering students a safe environment for joint exercises. The context is designed to resemble a real-life situation in which the represented professions commonly find themselves and the simulations (training sessions) take the form of roleplay based on relevant scenarios. The intended outcomes are ‘an increase in knowledge of how the other occupational group works and how to work with this group and an increase in subsequent confidence in future work with this group’ (Hlavac, Harrison, and Saunders Citation2022, 20). In this sense, IPE sessions are learning activities in which students studying for different professions collaborate on a task that they are likely to come across frequently in working life. These joint training sessions not only raise awareness of the professional roles of their fellow students, they also offer students hands-on experience of professional teamwork and interprofessional collaboration.

Recent developments in interprofessional education show that the method serves a variety of purposes, for example preparing students for working in complex interprofessional settings by developing interprofessional socialization and identities (Khalili et al. Citation2013; McGuire et al. Citation2020) and/or fostering collaborative professionals who can deal with interprofessional dilemmas and possess interdisciplinary cultural competencies in the workplace (Griswold et al. Citation2021). Recent publications on interprofessional education demonstrate the development of new pedagogical pathways – for example, how to facilitate interprofessional education in online environments (Hayward et al. Citation2021; Singh and Matthees Citation2021) and new methods for researching interprofessional practice (Iedema and Xyrichis Citation2021) – as well as the importance of institutional infrastructure to develop sustainable curricula for interprofessional education (Black et al. Citation2022; Potthoff et al. Citation2020). Interprofessional education is now slowly spreading to other professional and educational fields such as social sciences (Michalec Citation2022) and the humanities. In the past few years, a handful of studies have been published on interprofessional education involving interpreting students and students from other fields, mainly from the field of medicine and healthcare (Crezee and Marianacci Citation2022; Hlavac and Harrison Citation2021; Krystallidou et al. Citation2018) and occasionally also the field of political science and social work (Defrancq, Delputte, and Baudewijn Citation2022; Hlavac and Saunders Citation2021b). There is a call in the literature for further systematic studies of interprofessional education including interpreting students (Hlavac and Saunders Citation2021a, Citation2021b; Krystallidou Citation2022; Tipton and Furmanek Citation2016; Westlake and Jones Citation2018).

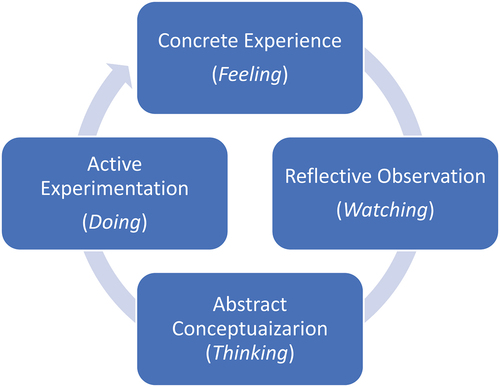

In this paper, IPE is treated as a situated learning activity (Wenger Citation1998) and an experiential endeavour (Kolb and Kolb Citation2005) in which participating students engage in different dimensions of learning. Experiential learning is to be regarded as a continuous process grounded in experience, and not strictly as an outcome. This is a student-centred approach to experiential learning based on a four-stage recursive experiential learning cycle (see ) that consists of: 1- concrete experience, i.e. doing and feeling the activity, 2- reflective observation, i.e. reflecting on performance in the activity, considering successes and failures, 3- abstract conceptualization, i.e. applying theory to the experience of doing the activity, and 4- active experimentation by considering theory and reflection to guide planning for subsequent experiences. The idea of a learning identity is key, emphasizing ‘the importance of prior knowledge, engagement with concrete experience where prior knowledge can be put into practice, reflections on the experience, forming theories about the experience, and engagement with new experience where the theories can be tested’ (Chan Citation2023, 22).

Figure 1. The experiential learning cycle model (adapted from Kolb and Kolb Citation2005).

In this sense, the IPE sessions can be regarded as learning spaces (Kolb and Kolb Citation2005), a physical or mental space where students and teachers can leave their comfort zone and enter into (hopefully) fearless, respectful communication and mutual exchanges of experience based on doing/feeling, reflecting and thinking, and experimenting. Establishing a trusting and supportive culture in the student groups as well as in the IPE activity is essential. The experiential dimensions of learning in the learning space can also offer an environment for implicit knowledge to be made explicit by articulating thoughts and experiences. The development of a learner identity, self-knowledge and the experiences from the learning activities can empower students, not only by helping them to learn more efficiently (in their own learning styles), but also by providing them with tools to take charge of their own present as well as future learning. Last, but not least, this IPE learning space offers students the opportunity to view themselves through the eyes of others in the process of acquiring their professional identities (Lave and Wenger Citation1991). The concept of experiential learning is present at all levels in the design of the IPE curriculum described in the following section.

Designing and developing interprofessional education

The design and development of interprofessional education involving different organizations is a multifaceted endeavour. In this section two different, however intertwined, perspectives relevant for the current case are discussed. The first perspective concerns the nature of and approach to Curriculum Design (Chan Citation2023; Crumly Citation2012; Emes and Cleveland-Innes Citation2003; O’Neill Citation2015) and the second, educational collaboration across organizations. The term curriculum refers to the structure and content of interprofessional training sessions as a pedagogical unit. The terms design and development refer to how the curriculum is planned, implemented and assessed. The design and development of the IPE curriculum is based on a spiral model of planning, implementing and evaluating the sessions recursively, each time drawing on the experiences gained during a full loop, and taking these into consideration when adapting and improving the next loop. As such, the spiral process is not finite; by default, it embraces the continuous improvement of the curriculum (Crumly Citation2012; Emes and Cleveland-Innes Citation2003). As students are the main stakeholders, their continuous influence over the curriculum is an important part of the process (Brooman, Darwent, and Pimor Citation2015; Chan Citation2023).

Designing a curriculum for interprofessional education adds an important layer of cross-faculty – or in the specific case, cross-university – collaboration. Literature on collaboration in educational settings bears witness to that fact that it is a complex and time-consuming process and highlights a number of prerequisites for achieving sustainable solutions (Fors and Berg Citation2018; Hlavac and Saunders Citation2021a; Perez Vico Citation2018). Sustainability in this context refers to the resilience and long-termed-ness of the collaboration and its results. Apart from committed partners at other organizations who are prepared to invest time and effort in the collaboration, geographical proximity is sometimes pointed out as a success factor (Hlavac, Harrison, and Saunders Citation2022). Other important factors relate to organizational aspects at various levels, such as establishing formal agreements between universities, faculties and/or departments, establishing a designated team working towards common goals, involving key staff in the joint project, and formalizing procedures that benefit the collaboration (see, for example, Hlavac and Saunders Citation2021a; Krystallidou et al. Citation2018). Sustainability runs through educational collaboration at several levels. It is reflected in the methodology of the curriculum design, which gives due consideration to the careful planning and design of the pedagogical content, the stepwise implementation and continuous improvement of the IPE curriculum, as well as the flexibility and capacity of the organization that will coordinate and teach it.

The setting and participants of the interprofessional education

The interprofessional education described in this article consists of a training session during which interpreting or social work students meet at a specific occasion to participate in and experience interpreter-mediated interaction. The first IPE session was held in autumn 2020 and similar sessions have been held with new groups during each subsequent spring and autumn semester. At the time of writing, the seventh IPE session is being planned. Students attending the IPE sessions are enrolled in the Social Work Study Programme at Linnaeus University and the Public Service Interpreting (PSI) program arranged at Stockholm and Lund Universities. The social work students attend IPE training sessions during their final (seventh) semester and students in PSI programs during the first of their two semesters of education.

As student groups are generally smaller in number in PSI programs than in the Social Work Study Programme, the PSI training programs at Stockholm and Lund universities collaborate extensively in a number of different ways in order to make an equal training partner with the Social Work Programme. One way is to involve students from other courses or interpreting teachers to provide sufficient number of students for the training session. The collaboration between the PSI programs is facilitated by the fact that a number of teachers teach at both universities and that a few teachers/researchers attend all sessions to observe and document the IPE activities, including the author of this paper. The collaboration between the PSI programs also helps balancing the differences in IPE training occasions needed. The Social Work Study Programme admits new students to the program every semester (twice a year) while the PSI programs admit students every second semester (once a year). In this paper, for the sake of simplicity, the two PSI programs will be referred to as the interpreting programs and the students in these programs as interpreting students when describing the IPE training sessions.

A majority of the interpreting students participating in the sessions are first- or second-generation migrants in Sweden and therefore may have personal experience of interpreter-mediated institutional encounters as clients. Moreover, a considerable number of interpreting students already work as interpreters in the public sectors. The social work students may also have previous experiences from interpreter-mediated encounters, sometimes based on personal experiences, but more often from previous workplaces, internships, voluntary work. These experiences are invaluable to the joint peer reflections. That said, in both student groups there are always a number of complete beginners who are engaging in interpreter-mediated interactions in these roleplay-based exercises for the first time.

A specific IPE team consisting of a group of teachers and researchers from each university was created. The IPE team members are responsible for planning and scheduling the sessions at their own universities. The members of the IPE team have a leading role in, for example, moderating the session, lecturing, grouping students and leading the joint reflections. Teachers from the PSI programs significantly outnumber those from the social work program, mainly because the PSI programs have language-specific subgroups, each with its own teacher(s). The number of PSI and social work teachers participating in these sessions usually varies from eight to twelve. The main task for the attending teachers outside the IPE team is to remain in the background and observe the interpreter-mediated role-play exercises. Only if needed – if a student asks for help, for example – will they offer feedback or discuss matters with the students. The general idea is that students should practice problem-solving independently (without the teachers’ support) and in collaboration. Observing this will offer the teachers present a shared experience of the IPE sessions with the students but also an abundance of input for future exercises and reflections in class after the IPE.

The structure and implementation of the IPE sessions

Interprofessional training sessions were introduced in autumn semester 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic. As they are held entirely online, geographical distance as well as travel time and expenses were never an issue. The current educational programs already used Zoom as a digital platform, which facilitated the joint planning and implementation of the training sessions. The collaborating programs also already used roleplay regularly in various ways during practical exercises, meaning that the IPE session was based on a familiar format. The three-hour timeframe allocated to the session is treated as a learning space (Kolb and Kolb Citation2005) including an introductory lecture, the training session and time for joint reflection. The cases used for roleplay were designed jointly by the members of the IPE team and reflect typical situations in which social workers and interpreters may meet and work together. In the roleplays, the social work students enact the social worker and the interpreting students enact the interpreter and, usually, also the client. Now follows an account of the implementation of the IPE session.

Before the IPE session

The IPE session is scheduled four to six months in advance, at the same time as the programs and courses are scheduled. Attendance at the first IPE session, held in November 2020, was voluntary and students were encouraged to participate. From 2021 onwards, the session is a compulsory course component. About one month before the IPE session, the IPE team starts the preparations for their respective student groups, a process that is handled separately at each university, adjusted to and integrated in local routines and platforms. Awareness of interprofessional collaboration and interpreter-mediated encounters is discussed in class in relation to the course literature and the upcoming IPE session. Reflections and ideas from the previous session are discussed in the IPE team and considered in planning. The roleplays are usually based on a social worker-parent encounter and focus on, for example, concerns expressed by the school regarding a student/child regularly missing class.

For social work students, preparations focus on the specific task of planning and managing the meeting with the parent, the current legislation and regulation related to minors, and how to build rapport with the parent and create a picture of the situation. For interpreting students, preparation is done in a number of different ways. For the role of the interpreter, the students have to prepare the necessary terminology related to current legislation and regulation, be aware of the general procedures during such meetings, the sensitiveness of the context, the agenda of the social worker, as well as the general goal of the meeting. For the role of the parent meeting with the social worker, the interpreting students need to put themselves in the parent’s situation with all the mixed feelings of fear, despair, shame, anger etc. The varying level of student experience, where some have extensive experience of participating in interpreter-mediated encounters while others have no experience at all, provides an interesting mix of perspectives when it comes to the joint reflections on the experiences made in the sessions and may offer eye-opening moments for both students and teachers. The need to prepare for double roles has been highlighted by the interpreting students themselves as challenging due to the additional workload. While sympathetic to the students’ arguments, teachers on the PSI programs underline the benefits of adopting a dual perspective, which may deepen the interpreting students’ understanding of the client’s situation. However, in order to test different solutions to this, different variants of grouping the interpreting students have been tested. One experiment involved mixing students from different interpreting course (different levels), with students on the introductory course playing one role and students on the advanced course the other. Another approach tested was to have students from the PSI program at one university play one role and students from the PSI program at the other university the other.

These experiments proved quite informative and taught the IPE team a number of things. The lesson learned is that it takes a considerable amount of time and effort to prepare students for playing the role of the parent alone, and requires more acting skill than one might expect. As a result, the instructions for the interpreting students and their different roles have developed considerably over the years. Another slightly surprising issue was the dynamics between the students enrolled in the introductory course and those enrolled in the advanced course of the PSI programs. The more advanced students showed a tendency to correct the more novice students from time to time, despite being specifically instructed not to do so, as this was not part of their role. Another lesson learned was that instructions on enacting different roles need to be elaborated in class in order to establish the necessary trust and mutual respect to roleplay with unfamiliar students in these joint training sessions.

During the IPE session

The IPE sessions last three hours and are divided into three phases. The first phase includes two parallel activities. Students and teachers gather in the main room in the online platform, where they attend a lecture by one of the teachers in the IPE team about the relevance of the shared experiences from the perspective of all involved parties, the goals of the joint training session, the schedule and division of roles, as well as the code of conduct during the different phases of the IPE session. At the same time, in the background, other IPE team members organize the breakout rooms in which students will engage in joint training. Even though the number of students in each program is known beforehand, unforeseen events such as illness or unstable internet connections may affect the number of attendees affecting the grouping. The careful grouping of the students is vital. At a minimum, a training unit must consist of one social work student and two PSI students sharing the same working languages. If the groups include several students from the different programs, the students take defined roles such as observers, timekeepers, notetakers and moderators for the brief peer reflection sessions following immediately after each interpreter-mediated encounter.

The second phase is the joint training session, which takes place in small groups as described above. The students enter the different breakout rooms and start organizing the training session by allocating roles and responsibilities according to previous instructions. Each interpreter-mediated encounter lasts for about 15–20 minutes, enough time for approximately three sets of interpreter-mediated interactions during the session. Each individual interaction is followed by a very brief joint reflection on the encounter just performed and/or observed. During this second phase, teachers move between the groups, interacting only when necessary or when invited to do so.

After a short break, the third and final phase starts in the main room in the online platform. This phase is intended for joint peer reflections and exchanges of thoughts and ideas, and is moderated by one of the teachers/researchers in the IPE team. The idea is not only to participate and experience the collaboration in the interpreter-mediated encounter, but also to learn from joint reflections on these experiences (Kolb and Kolb Citation2005). Students from the different programs are encouraged to verbalize their thoughts and feelings as a way of shaping their learning identity together with their peers (Chan Citation2023, 160). These joint reflection sessions offer a learning space where previous knowledge can be shared, questions posed and mutual appreciation expressed. In order to include students in the discussions, the joint reflection sessions were subsequently organized in three breakout rooms, each with some 20 students and teachers moderated by a member of the IPE team. During the final few minutes of the session, the participants relocate to the main room where they receive a link to an anonymous questionnaire that is used to assess the joint training session. The function of the questionnaire in the design and development of the IPE session is described in the following section.

Interestingly, while the overall structure and contents of the IPE sessions have remained relatively stable over the years, there has been a gradual change in the division of time between the three phases. Improvements in, and more precise student instructions and preparations before, the IPE sessions has resulted in less time need for instructions during the session, making more time available for roleplays. This in turn, has resulted in a shift of the aim initially described as experiencing participation in interpreter-mediated interaction to performing an interpreter-mediated encounter. This can be seen as a significant improvement in the IPE curriculum and the implementation of it.

After the IPE session

The multi-purpose post-IPE questionnaire has been an important source of feedback from participating students to the IPE team and crucial in developing the joint training sessions.

The questionnaire was designed to address the following four themes. One group of questions concerned the background of the respondents, including which program they were enrolled in. While the members of the IPE team had a good understanding of the intended learning outcomes for their own students, they needed a deepened understanding of the other student groups in order to develop the sessions. As the questionnaire developed, questions about the roles enacted in the roleplays and previous experiences of interpreter-mediated encounters were added. The second theme was related to student satisfaction. These questions were initially generally formulated, asking the students to grade their satisfaction on a scale and describe rewarding and challenging aspects in free text. Further questions on peer feedback, the types of instructions and how well-prepared students felt to take part in the training session were soon added to this theme. The third theme focused on self-evaluated learning outcomes. The free response answers offered detailed and elaborated feedback regarding eye-opening experiences and new knowledge acquired from the collaboration between the student groups. The fourth and final theme in the questionnaire contained a set of questions relating to the organization of the sessions. The IPE team used the opportunity to include questions of immediate relevance to the implementation of the sessions. One such question targeted the online training format and reflects the novelty of that format in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. Another question was whether the joint training session was embedded in the relevant course and semester of the educational program. Questions such as these were removed from the questionnaires as soon as they stopped being subject to inquiry.

Each implementation round gave rise to new practical and theoretical questions, for which the questionnaire was used to explore and find answers. As such, the post-IPE questionnaire has been a powerful tool for the design and development of the IPE sessions. below gives an overview of the scope of student assessment.

Table 1. Overview of the number of students in the training sessions.

It is worth noting that the post-IPE assessment was used as a unidirectional source of feedback, from the students to the IPE team. This means that the questionnaire at this stage of curriculum development was not designed as systematic student assessment. Also, the questionnaire was one of several sources of feedback to the IPE team. The responses to the questionnaire, together with observations of, and fieldnotes from, the roleplay sessions and the joint reflections, provided the IPE team with detailed feedback for planning and adapting future IPE sessions loops.

Concluding discussions

This article has described the design and development of an interprofessional education including social work and interpreting students. This section discusses the question around which these training sessions have been organized, namely:

What is required to establish a sustainable curriculum for interprofessional education to prepare social work and interpreting students to manage interpreter-mediated social work encounters?

Below, two separate but intertwined perspectives are addressed when answering this question. The first perspective focuses on the pedagogical aspects of the IPE, and the second one on the organizational, collaborational aspects.

From a pedagogical perspective, a broadened and deepened awareness of language and communication as professional tools has been important for both social workers and interpreters. For the social work students, the IPE sessions have offered an opportunity of hands-on experiences in planning an interpreter-mediated encounter and preparing for a collaborative conversation in order to improve participation on behalf of the clients. Doing this, social work students have experienced the amount of time needed for interpreter-mediated encounters compared to encounters without interpreters, and awareness of the attention needed when phrasing questions. Social work students have also had the opportunity to reflect on these experiences with their coursemates as well as students and teachers from the interpreting programs. Reflection is a powerful tool for capturing tacit knowledge, deepening awareness of one’s profession, and offers an opportunity of viewing oneself through the eyes of others (Lave and Wenger Citation1991; Wenger Citation1998). Not surprisingly, the discussions have time and again concerned the amount of talk that the social worker can produce before it gets too much for the interpreter to handle. The fact that it is not always easy to express yourself clearly and in short phrases, or to think aloud and reason together, or to chitchat when the conversation is mediated by an interpreter, is usually an eye-opener. These aspects relate directly to the peculiarities of turn organization in interpreter-mediated conversation. Other aspects reflected upon regularly are how to handle the situation if, for example, one of the parties does not follow what is said. What is a smooth way to interrupt the other party? Whose responsibility is it, the social worker’s or the interpreter’s, to act? How can you slow down the pace of talk generally or to inform the client to speak slower? These aspects relate to the responsibilities and division of work between social workers and interpreters during the encounter.

For interpreting students, the IPE is an excellent opportunity for both drilling general interpreting routines as well as practicing specific skills. General interpreting routines refer to practicing renditions and coordination of interpreter-mediation with unfamiliar participants and unfamiliar ways of speaking. Quick analyses of the individual speaker’s dialects, use of professional jargon and the information density in speech are among the general professional skills of interpreters. The specific skills for interpreter students in this context refer to, for example, the context in which the encounter takes place, here a social work context, understanding the idea of a collaborative communicative format and improving client participation without abandoning the ethical guidelines of impartiality and neutrality. Not surprisingly, these issues are brought up frequently in the joint reflections.

From an organizational perspective, the need for training in specific professional skills can be highlighted as a driving force, and that none of the programs were able to offer this type of training for this end on their own. This motivated the investment of necessary time and effort over several semesters on behalf of the collaborating parties. Another important aspect at an overall level was the way in which this cross-university collaboration unfolded. The collaboration proceeded in an informal manner and at local, departmental level, without formal financing. Lack of formal financing is often highlighted as a challenge. However, in designing and developing the current IPE curriculum the gradual and small-scale format of the collaboration over time was rather an advantage as it allowed stepwise integration of the curriculum in the different local educational systems. At an overall level, the crucial aspects for establishing a sustainable IPE have been the actual needs, the persistence over time and small-scaleness of the development process. Another important aspect, without which this IPE collaboration would not have been possible is the online format. The online format made possible the collaboration between the current universities located in different geographical areas in the country, and connecting student groups that otherwise would not have come together. At a local level, two specific aspects need to be pointed as crucial in the current case. The first is the close collaboration between the interpreting programs at Stockholm and Lund Universities, without which the IPE sessions would not have materialized. The second one is the establishment of the informal IPE team, populated by teachers and researchers at the different universities. The members of the IPE team made sure that the preparations for the IPE sessions were integrated, according to local routines and practices.

The general feedback from the student groups has been consistently positive and after six session over a period of three years we are now confident to say that we have designed a pedagogically and organizationally sustainable IPE for social work and interpreting students. However, the work is by no means complete. With an IPE organization in place, now starts the work of maintaining the IPE and continuously adjusting the curriculum to the changing needs of the educational programs. One way forward could be to use the IPE sessions more systematically as a source to develop different exercises used before and after the IPE sessions. This suggests a more systematic use of the IPE sessions and would have implications for the IPE team and the teachers involved. Opening the path for a new pedagogical area as this would require specific teacher training for coaching and scaffolding students before, during and after the IPE sessions. Another way forward could be to vary the exercises by new implementation of the roleplays, for example by offering training in telephone interpreting of different sorts with partial or no visual input during the encounter. In sum, having established a sustainable IPE involving social work and interpreting students, there are now plenty of possibilities to systematically develop the content and format of the IPE’s to prepare prospective social workers and interpreters for collaboration and service in a linguistically diverse society.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Andersson, E., R. Smith, and M. Hammick. 2016. “Evaluating an Interprofessional Education Curriculum: A Theory-Informed Approach.” Medical Teacher 2016 (38): 385–394. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2015.1047756.

- Black, E. W., L. Romito, A. Pfeifle, and A. V. Blue. 2022. “Establishing and Sustaining Interprofessional Education: Institutional Infrastructure.” Journal of Interprofessional Education & Practice 26 (2022): 100458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xjep.2021.100458.

- Brooman, S., S. Darwent, and A. Pimor. 2015. “The Student Voice in Higher Education Curriculum Design: Is There Value in Listening?” Innovations in Education and Teaching International 52 (6): 663–674. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2014.910128.

- Buzungu, H. F. 2023. Language Discordant Social Work in a Multilingual World: The Space Between. Milton: Taylor and Francis Group.

- Chan, K. Y. C. 2023. Assessment for Experiential Learning. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003018391.

- Chouc, F., and J. Maria Conde. 2016. “Enhancing the Learning Experience of Interpreting Students Outside the Classroom. A Study of the Benefits of Situated Learning at the Scottish Parliament.” The Interpreter and Translator Trainer 10 (1): 92–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2016.1154345.

- Crezee, I., and A. Marianacci. 2022. “‘How Did He Say that?’ Interpreting students’ Written Reflections on Interprofessional Education Scenarios with Speech Language Therapists.” The Interpreter and Translator Trainer 16 (1): 19–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2021.1904170.

- Crumly, C. L. 2012. “Designing a Student-Centered Learning Environment.” In Pedagogies for Student-Centered Learning. Online and On-Ground, edited by C. L. Crumly, P. Dietz, and S. d’Angelo, 73–91. Media: Fortress Press.

- Defrancq, B., S. Delputte, and T. Baudewijn. 2022. “Interprofessional Training for Student Conference Interpreters and Students of Political Science Through Joint Mock Conferences: An Assessment.” The Interpreter and Translator Trainer 16 (1): 39–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2021.1919975.

- Emes, C., and M. Cleveland-Innes. 2003. “A Journey Toward Learner-Centered Curriculum.” The Canadian Journal of Higher Education XXXIII (3): 47–70. https://doi.org/10.47678/cjhe.v33i3.183440.

- Fors, V., and Berg M. 2018. Samproduktionens pedagogik [The pedagogy of co-production]. In: M. Berg, V. Fors, & R. Willim (eds.), Samverkansformer: Nya vägar för humaniora och samhällsvetenskap [Forms for collaboration: New pathways in Humanities and Social Sciences], 93–111. Lund: Studentlitteratur AB.

- González-Davies, M., and V. Enríquez-Raído. 2016. “Situated Learning in Translator and Interpreter Training: Bridging Research and Good Practice.” The Interpreter and Translator Trainer 10 (1): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2016.1154339.

- Griswold, K., K. Isok, M. Denise, S. May, Z. Karen, D. Lie, and P. J. Ohtake. 2021. “Interpreted Encounters for Interprofessional Training in Cultural Competency.” Journal of Interprofessional Education & Practice 24 (2021): 100435. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xjep.2021.100435.

- Gustafsson, K., E. Norström, and L. Åberg. 2022. “The Right to an Interpreter: A Guarantee of Legal Certainty and Equal Access to Public Services in Sweden?” Just Journal of Language Rights and Minorities, Revista de Drets Lingüístics I Minories 1 (1–2): 165–192. https://doi.org/10.7203/Just.1.24781.

- Hayward, K., M. Brown, N. Pendergast, M. Nicholson, J. Newell, T. Fancy, and H. Cameron. 2021. “IPE via Online Education: Pedagogical Pathways Spanning the Distance.” Journal of Interprofessional Education & Practice 24 (2021): 100447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xjep.2021.100447.

- Hlavac, J., and C. Harrison. 2021. “Interpreter-Mediated Doctor-Patient Interactions: Interprofessional Education in the Training of Future Interpreters and doctors”.” Perspectives Studies in Translation Theory and Practice 29 (4): 572–590. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2021.1873397.

- Hlavac, J., C. Harrison, and B. Saunders. 2022. “Interprofessional Education in Interpreter Training.” Interpreting 24 (1): 111–139. https://doi.org/10.1075/intp.00072.hla.

- Hlavac, J., and B. Saunders. 2021a. “Interprofessional Education for Interpreting and Social Work Students—Design and Evaluation.” International Journal of Interpreter Education 13 (1): 19–34. https://doi.org/10.34068/ijie.13.01.04.

- Hlavac, J., and B. Saunders. 2021b. “Simulating the Context of Interpreter-Mediated Social Work Interactions via Interprofessional Education.” Linguistica Antverpiensia, New Series: Themes in Translation Studies 20:186–208. https://doi.org/10.52034/lanstts.v20i.595.

- Iedema, R., and A. Xyrichis. 2021. “Video-Reflexive Ethnography (VRE): A Promising Methodology for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice Research.” Journal of Interprofessional Care 35 (4): 487–489. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2021.1943124.

- Khalili, H., C. Ochard, H. K. Spence, H. K. Laschinger, and R. Farah. 2013. “An Interprofessional Socialization Framework for Developing an Interprofessional Identity Among Health Professions Students.” Journal of Interprofessional Care 27 (6): 448–453. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2013.804042.

- Kolb, A., and D. Kolb. 2005. “Learning Styles and Learning Spaces: Enhancing Experiential Learning in Higher Education.” Academy of Management Learning and Education 4 (2): 193–212. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2005.17268566.

- Krystallidou, D. 2022. “Interprofessional Education … Interpreter Education, in or And. Taking Stock and Moving Forward.” L. Gavioli and C. Wadensjö (eds.). In: Routledge Handbook of Public Service Interpreting. Vol. 2022, Milton: Taylor and Francis Group, 383–398.

- Krystallidou, D., C. Van De Walle, M. Deveugele, E. Dougali, F. Mertens, A. Truwant, E. Van Praet, and P. Pype. 2018. “Training ’doctor-minded’ Interpreters and ’interpreter-minded’ Doctors. The Benefits of Collaborative Practice in Interpreter Training.” Interpreting 20 (1): 126–144. https://doi.org/10.1075/intp.00005.kry.

- Lave, J., and E. Wenger. 1991. Situated Learning. Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- McGuire, L. E., A. L. Stewart, E. K. A. Akerson, and J. W. Gloeckner. 2020. “Developing an Integrated Interprofessional Identity for Collaborative Practice: Qualitative Evaluation of an Undergraduate IPE Course.” Journal of Interprofessional Education & Practice 20 (2020): 100350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xjep.2020.100350.

- Michalec, B. 2022. “Extending the Table: Engaging Social Science in the Interprofessional Realm.” Journal of Interprofessional Care 36 (1): 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2021.1997948.

- O’Neill, G. 2015. Curriculum Design in Higher Education: Theory to Practice. University College Dublin. Teaching and Learning. http://www.ucd.ie/t4cms/UCDTLP0068.pdf.

- Perez Vico, E. 2018. “En översikt av forskningen om samverkansformer och deras effekter [An overview of the research on collaboration forms and their effects].” In Samverkansformer: Nya vägar för humaniora och samhällsvetenskap [Forms for collaboration: New pathways in Humanities and Social Sciences], edited by M. Berg, V. Fors, and R. Willim, 29–50. Lund: Studentlitteratur AB.

- Piller, I. 2016. Linguistic Diversity and Social Justice: An Introduction to Applied Sociolinguistics. 1st ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Potthoff, M., J. Doll, A. Maio, and K. Packard. 2020. “Measuring the Impact of an Online IPE Course on Team Perceptions.” Journal of Interprofessional Care 34 (4): 557–560. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2019.1645647.

- Singh, J., and B. Matthees. 2021. “Facilitating Interprofessional Education in an Online Environment During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Mixed Method Study.” Healthcare 2021 (9): 567. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9050567.

- Tipton, R., and O. Furmanek. 2016. Dialogue Interpreting. A Guide to Interpreting in Public Services and the Community. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Wadensjö, C. 1998. Interpreting as Interaction. London: Longman.

- Wenger, E. 1998. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Westlake, D., and R. Jones. 2018. “Breaking Down Language Barriers: A Practice-Near Study of Social Work Using Interpreters.” British Journal of Social Work 48 (5): 1388–1408. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcx073.

- WHO [World Health Organization]. 2010. Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice. Geneva: World Health Organization.