Abstract

This paper investigates public preferences for biodiversity conservation in Vietnam’s Tam Dao National Park by emphasizing the conservation of ecosystems and the protection of the endemic species Opisthotropis tamdaoensis (Tam Dao stream snake). A contingent valuation survey was conducted using face-to-face interviews with 250 residents in Hanoi. According to the results, 89.7% of the respondents were willing to pay an average of VND35,250 (US$1.63) to conserve the ecosystem, and 77.2% were willing to pay an average of VND21,571 (US$1.0) to protect O. tamdaoensis. The motivation behind the respondents’ willingness to pay (WTP) was the value of biodiversity, whereas that behind their refusal to pay was a lack of transparency in the budget disbursement process. Among various socioeconomic characteristics, the education level and monthly income of respondents had a significant effect on WTP.

Introduction

According to the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), there are currently 102,102 protected areas characterized by rich biodiversity and specific ecosystems or species across the world (Jenkins et al. Citation2004). Many scholars have stated that biodiversity provides a wide range of benefits to human life (Nelson et al. Citation2009), including people’s wellbeing, health, livelihood, and survival (De Groot et al. Citation2012; Christie et al. Citation2012; Costanza et al. Citation2014) and, in this regard, the role of ecosystem services has been increasingly recognized in resource management decisions (Nelson et al. Citation2009). The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment recently observed that “ecosystem services are the benefits people obtain from ecosystems” (Engel et al. Citation2008; Mace et al. Citation2012). According to the World Bank, there are more than one billion extremely poor people directly supported through ecosystem services. This implies that the ecosystem is a critical source of economic development and poverty mitigation (2006, cited in Turner et al. Citation2007).

However, the ability of ecosystem services to provide for present and future generations is threatened because of ecosystem degradation and biodiversity loss through human activity and economic development (De Groot et al. Citation2012). In this context, the value of biodiversity and ecosystem services should be considered in monetary terms, not as inexhaustible and free public goods. Further, the expressed monetary value of biodiversity and ecosystem services is not only an important tool in decision making to obtain a general consensus on more equitable and sustainable policies, but also a way to understand public preferences for ecosystem services (Christie et al. Citation2012; De Groot et al. Citation2012).

In the last few decades, many measurement methods have been proposed to assign value to ecosystem services (Christie et al. Citation2012). Costanza et al. estimated the value of global annual ecosystem services at about US$33 trillion (at 1995 values) (1997, cited in Costanza et al. Citation2014). Since their finding, increased attention has been paid to the valuation of ecosystem services. De Groot et al. (Citation2012) indicated that the total value of ecosystem services can be considered mainly as a non-tradable public benefit. In 2011, total global ecosystem services were estimated at US$145 trillion/year (at 2007 values) (Costanza et al. Citation2014).

At the local level, the monetary value of ecosystem services is useful for decision makers evaluating policies on biodiversity conservation. The value varies widely according to the location because of differences in local circumstances and socioeconomic conditions (De Groot et al. Citation2012).

Nuva et al. (Citation2009) estimated the benefit of conserving ecotourism resources at Indonesia’s Gunung Gede Pangrango National Park to be RP452 million (US$44,400). In addition, income, gender, and the residential area had significant effects on visitors’ willingness to pay (WTP). Similarly, Yoeu & Pabuayon (Citation2011) estimated the WTP for conserving the flooded forest of Cambodia’s Tonle Sap Biosphere Reserve at US$0.64 per month and found it to be influenced by age, income, and training program participation. Further, the level of awareness was high among visitors in terms of benefits and functions of the flooded forest because most visitors were members of conservation programs for the flooded forest. In addition, village leaders were found to be ideal collectors of the WTP fund.

Coral reefs not only require biodiversity conservation but can also offer substantial resources for scuba diving in Thailand. Therefore, many studies have estimated the benefit of tourism from coral reefs. Based on the travel cost method (TCM) and the contingent valuation method (CVM); for example, Udomsak (Citation2003) estimated the total value of tourism for Phi Phi Island coral reefs at US$497.38 million a year, with visitors’ mean WTP varying depending on the method – the mean WTP of domestic vicarious users based on the CVM was US$15.85, whereas that of domestic visitors based on the TCM was US$7.17. Asafu-Adjaye & Tapsuwan (Citation2008) found the WTP of divers for exploring coral reefs in Thailand’s Mu Ko Similan Marine National Park to be higher based on the CVM. The WTP ranged from US$27.07 to US$62.64 per person per annum, bringing the range of WTP for coral reefs to between US$31 million and US$71 million.

On the other hand, Indab (Citation2007) found the people of Sorsogon in the Philippines to be less willing to pay for conserving whale sharks. However, this does not necessarily mean that people in developing countries are less willing to pay for conserving wildlife. Truong (Citation2007) used the CVM to estimate the total potential revenue from conserving the Vietnamese rhino in Vietnam's Ho Chi Minh City and Hanoi at US$5.8 million, which exceeded the cost of conservation.

Previous studies have examined public preferences for various attributes of biodiversity in Vietnam. The estimated recreational value of coral reefs surrounding the Hon Mun Islands ranged from US$8.7 million to US$17.9 million (Pham & Tran Citation2004). The total monetary value of improving wetlands at Vietnam’s Tram Chim National Park was estimated in three large cities at US$5.4 million (Do & Bennett Citation2007). Dang & Nguyen (Citation2009) and Tran & Bui (Citation2013) indicated substantial differences in Vietnamese people's preferences for biodiversity services with respect to socioeconomic characteristics such as education level, bid amounts, and household income.

Vietnam is recognized as a biodiversity-rich country with many special ecosystems and endemic species not found anywhere else in the world. Biodiversity is a type of natural capital that can bring huge economic benefits, but its value remains poorly examined and understood. However, rapid economic growth in recent decades has led to the sharp deterioration of biological diversity in developing countries, particularly in Vietnam. The loss in biodiversity is alarming, and therefore there is a need for effective policies to mitigate this problem. However, no study has considered people's preferences in the context of the value of biodiversity as an input for policy makers.

Under Vietnam's constitution all natural resources, including biodiversity and associated ecosystem services, are managed by the state and specific government agencies. Despite the increasing need to protect certain areas, public funding for biodiversity conservation, particularly in developing countries, remains limited. Therefore, there is an urgent need to involve ecosystem service users in financing ecosystem services (Jenkins et al. Citation2004).

Tam Dao National Park is a protected area with high biodiversity values and a variety of ecological functions, including 39 endemic animal species of which 11 live only in Tam Dao National Park. In particular, the Tam Dao stream snake (Opisthotropis tamdaoensis) is listed in the Red List of the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources as an endemic data deficient species, indicating that tourism activities might cause an adverse effect on the habitat of this species. This study examines preferences of people in Hanoi, Vietnam, for conserving ecosystems and protecting O. tamdaoensis. In this way, the study offers important insights for policy makers interested in involving people in biodiversity conservation and raising social awareness of ecosystem services.

Methods

The contingent valuation method and a dichotomous choice questionnaire

Biological diversity provides people with use as well as non-use value. Use value is derived from the direct use of resources such as timber and meat which can be commercially traded. However, non-use value refers to services and functions of nature, such as recreation, bird-watching, and clean air (Primack Citation2006). In this sense, biodiversity services represent a type of public good that cannot be commercially evaluated. Instead, its value can be estimated by applying non-market estimation methods. There are two types of these – revealed and stated preferences (Ji et al. Citation2013). Revealed preferences methods include the TCM and the hedonic pricing method. These measure the value of public goods by observing the actual market, whereas stated preferences methods use a hypothetical market and elicit the respondent’s WTP or willingness to accept (WTA; Christie et al. Citation2012). Because of their approaches and characteristics, revealed preferences are often used to estimate use value, whereas stated preferences are considered for total economic value.

This study employs the CVM, the most frequently applied method in valuing environment components and biodiversity attributes. In general, public goods are not excludable and not rivals, so a limitation in valuing public goods is that they cannot be traded in a formal market with a specific price. In CVM surveys, people are asked about their WTP for avoiding a reduction in utility or their WTA in the case of a decrease in utility under various assumed conditions. The CVM is expected to overcome the aforementioned limitations of public goods. Therefore, the total monetary value of public goods can be calculated by aggregating WTP/WTA based on the total number of consumers. In this regard, the CVM may be the only practical method for uncovering existence value, which is neither assigned and defined in the market nor substituted and complemented (Tyrvainen & Vaananen Citation1998; Tong et al. Citation2007; Lee & Mjelde Citation2007; Dang & Nguyen Citation2009).

However, the CVM is generally limited as a result of its reliance on individuals' stated WTP under a given hypothetical market scenario that does not elicit people's responses in real life (Lee & Mjelde Citation2007). Another bias may occur when people do not want to reveal their WTP or WTA. In the CVM, there are two main types of WTP questions: direct or open-ended; and dichotomous questions. The latter can help avoid some bias in answers such as outliers (Dang & Nguyen Citation2009). Dichotomous choice questions offer the respondent a given bid and then ask them to accept or reject it (Lafta Citation2013).

The model

This study employs the dichotomous choice model. In this model, bids are given to respondents instead of directly asking them the amount of money that they are willing to pay. Empirically, the respondent may be asked a WTP question about some goods in a single-bounded model or two questions in a double-bounded model. This study uses a double-bounded questionnaire model.

WTP for conserving ecosystems and protecting the endemic species O. tamdaoensis is a compensating surplus and influenced by individual characteristics as well as various unknown random variables. Therefore, all variables must be included in the model.

This study analyzes the probability of WTP in the first given bid. The j-th individual's WTP function can be written as CSj = γSj + ej. In this case, the probability of j’ favoring biodiversity conservation can be illustrated as follows (Ji et al. Citation2013):(1)

If ej has zero mean and follows a normal distribution, then another random variable also follows a normal distribution. The probability in favor of the presented amount is

. The likelihood function and parameters can be derived with a maximum likelihood estimate (Ji et al. Citation2013).

The WTP of the chosen sample can be estimated in two ways: mean and median WTP. The mean is estimated using the following equation (Lafta Citation2013):(2)

Median WTP can be calculated as the middle number of all bids after putting all observations in ascending order.

Estimation of influential factors

To determine the factors influencing WTP, another model should be developed to test the significance of each potential factor. Two groups of factors are specified, and then factors within each group are tested to determine whether they influence WTP. In this study, these two groups are economic and socioeconomic factors, and therefore WTP can be written as follows:(3)

A multi-response model is more suitable for describing the probability of each outcome. Because the dependent variable of WTP in this study consists of two logically ordered values such that 0 is not willing to pay and 1 is willing to pay, a logit model is applied to test the factors influencing WTP (Lafta Citation2013).

The survey

A survey was administered to people living and working in Hanoi, the capital of Vietnam. A contingent value questionnaire was used through face-to-face interviews with 250 random residents of Hanoi. However, some respondents did not complete WTP questions, and therefore there were 224 accepted responses for the final analysis (a response rate of 89.6%). A pre-survey was conducted between 15 and 30 March 2015, and the survey was conducted between 4 April and 18 May 2015.

The type of payment vehicle has considerable influence on the respondent’s WTP, which may be a large or small burden to the interviewee and thus change his or her WTP amount. Payment vehicles include entrance fees, utility bills, property taxes, sales taxes, special funds and prices, and income taxes (Akcura Citation2015). This study employs admission fees because of their familiarity for activities at tourism sites.

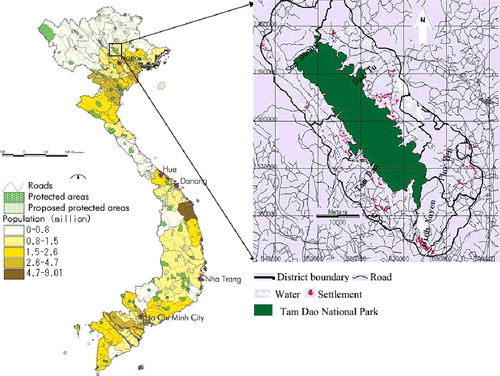

The contingent valuation questionnaire was carefully designed to clarify the hypothetical market situation. The respondents were informed that the survey would be used for academic purposes to examine the economic value of biodiversity at Vietnam’s Tam Dao National Park for the species O. tamdaoensis, not for actual prices to visitors. This allowed the respondents to feel more comfortable in revealing their true WTP and reduced the possibility of their giving misleading responses or rejecting the survey. This park was chosen as the subject of conservation not only because of its rich biodiversity but also because of the conflict between biodiversity conservation and economic development. The park was located about 85 km northwest of Hanoi in a large area covering Vinh Phuc, Tuyen Quang, and Thai Nguyen Provinces (). It was designated as a conservation area in 1977 by the central government. The park covers a total of 34,995 ha and is well known for its rich biodiversity and ecosystems with a wide variety of endemic and rare species. In addition, because of its proximity to the city, the park offers an accessible recreational environment for urban residents.

The questionnaire consisted of four parts. The first part introduced the current state of biodiversity and the value of the park as well as the impact of economic development on the park's biodiversity. The second part had general questions about the respondent's attitudes toward environmental issues. The third part included questions about WTP. After the hypothetical condition was explained, the respondents were asked the question: “Are you willing to pay <bid 1> as an admission fee that would be used to conserve the ecosystem at Tam Dao National Park?” If the answer was “yes” then a 20% increase in the amount was applied, and the question was asked again. If the answer was “no” then a 20% reduction was applied, and the question was asked again. Similarly, the respondents were asked to pay the admission fee as a way to help protect O. tamdaoensis at the park. Afterward, the respondents were asked to choose the reason why they decided to pay or not to pay the admission fee.

The pre-survey was conducted with 80 randomly selected graduates who chose a number of suggested amounts. They were asked to choose between the following amounts to conserve the ecosystem and protect the endemic species O. tamdaoensis: VND0, VND1000, VND2000, VND5000, VND10,000, VND20,000, VND30,000, VND40,000, VND50,000, and VND100,000 (US$1 = VND21,625 at the time of the survey). Average results were used to set presented bids. In the first question about conserving the ecosystem, one of three amounts (VND28,000, VND35,000, and VND42,000) was randomly selected and presented to each respondent as the admission fee per person. Similarly, for protecting O. tamdaoensis, the bids were VND20,000, VND25,000, and VND30,000. In the second question, a 20% higher or lower amount relative to the first bid was presented, depending on the answer to the first question.

Results and discussion

describes the sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents. The sample was biased toward young, highly educated respondents. The respondents’ ages ranged from 18 to 68 (employable age range). The average age was 37. The respondents were equally distributed in terms of gender (49.6% female and 50.4% male). Among the respondents, 52.2% had a university degree or more. The average income of the respondents was consistent with that of Vietnam's lower middle class.

Table 1. Basic statistics for socioeconomic characteristics of respondents.

Regarding attitudes toward biodiversity conservation as part of environmental issues, the deterioration of biodiversity was ranked as least important (). These results are consistent with the findings of Do & Bennett (Citation2007) in Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City, and Cao Lanh, which suggest wetland biodiversity conservation to be least important in all three locations. Therefore, among various environmental issues, biodiversity was not a priority concern among urban residents.

Table 2. Priority ranking of environmental issues.

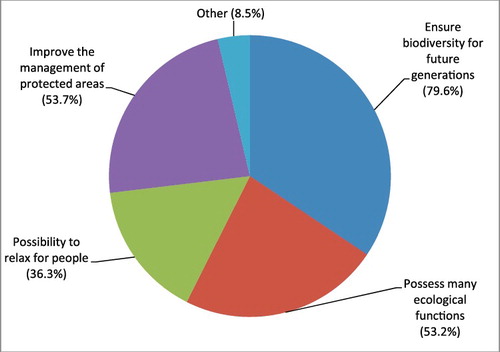

A majority of the respondents were willing to pay to conserve the ecosystem of Tam Dao National Park. The probability of acceptance varied from 78.67% to 84% (). This is different from the findings of Tran & Bui (Citation2013), who examined the WTP of people for the conservation and restoration of Vietnam's mangrove forest. They found that the probability decreased with an increase in the bid and that the probability of acceptance for conserving the ecosystem was highest for the average bid. Because the average offer was decided based on pre-survey results, and three sets of offers were given to test the payment vehicle, this outcome shows some similarity between the chosen payment vehicle and pre-survey results. The main motivation behind people’s WTP was either to ensure biodiversity for future generations or to improve and protect ecological function (). The main reason for not paying was either little interest in conservation issues or no interest in biodiversity at the national park. Some respondents did not trust the management organization, as indicated by their concern that their contributions would not be used for conservation purposes.

Table 3. Probability of acceptance for ecosystem conservation.

Opisthotropis tamdaoensis is known to exist only at Tam Dao National Park. No species-specific conservation measures were in place elsewhere. The Opisthotropis species is found in forest streams, and therefore may be at risk from deforestation. In response to the WTP question, 77.2% of the respondents were willing to pay an admission fee to help protect O. tamdaoensis. Their WTP ranged from VND16,000 to VND36,000 because of their ecological value and preferences for biodiversity conservation. A few respondents declared zero WTP, indicating that they distrusted the problem-solving capability of the payment. Income had little effect on the respondents’ refusal to pay for either biodiversity or O. tamdaoensis conservation.

Noteworthy is that 39.2% of the respondents who refused to pay stated that biodiversity conservation should be the responsibility of the government through its tax revenue. This result is similar to the findings of Truong (Citation2007) who examined Vietnamese rhino conservation and found that 38% of all respondents did not believe that the money would actually be used for rhino conservation. It is also consistent with the findings of Dang & Nguyen (Citation2009) with regard to Lo Go–Xa Mat National Park. They found that 28.9% of respondents answering “no” to the WTP question thought that it should be the government's responsibility, 9.8% did not believe that paying would solve the problem, and 15.3% did not trust the management institution to appropriately handle money for preservation work. This suggests that Vietnamese people are not likely to trust management organizations.

The single- and double-bounded models had 224 responses. shows the estimation results for WTP for conserving the ecosystem at Tam Dao National Park. Generally, in Vietnam, the admission fee of a national park is determined by the Ministry of Culture, Sport and Tourism's regulations and the National Park Board of Managers. For Tam Dao National Park, visitors have to pay an entrance fee of VND40,000. When we conducted the survey for this study, we explained about the hypothetical admission fee for the respondents. The hypothetical admission fee for conserving biodiversity and O.tamdaoensis in the park is an extra fee to be paid on top of the park’s entrance fee. The mean WTP in the single-bounded model was VND28,562 (US$1.32), whereas that in the double-bounded model was VND35,250 (US$1.63). The results show that the double-bounded model partly addressed the limitation in terms of the respondents being asked to pay in a hypothetical market, and the respondents’ WTP in this model was also higher than that in the single-bounded model. The WTP level is consistent with the pre-survey result (VND36,087) for highly educated respondents.

Table 4. Estimation results for WTP for ecosystem conservation (in US$).

Public valuation studies of biodiversity conservation, ecosystems, and nature services have employed many methods. Among such studies, some have estimated the WTP of Vietnamese people for conserving biodiversity or ecosystems and found it to vary between US$0.46/visit and US$6.3/household/year. Nguyen & Tran (Citation1999) found that people were willing to pay US$0.95/visit to improve biodiversity conservation facilities at Cuc Phuong National Park. Dang & Nguyen (Citation2009) estimated that the respondents were willing to pay US$0.46/person for biodiversity conservation at Lo Go–Xa Mat National Park. According to the data of the World Bank, Vietnam's purchasing power parity (PPP) GDP per capita (and actual GDP per capita) has increased from US$1850 (US$374.48) in 1999, to US$2900 (US$606.09) in 2004, and US$5370 (US$2052.3) in 2014. Although it is difficult to directly compare the results of this study with those of other studies because of differences in study settings, social inflation rates, and interest rates, the ratio between PPP GDP per capita and actual GDP per capita may provide a good agent to compare the findings of other studies that were conducted at a different time. The level of this WTP is lower than that of compensation for recreational value for the Hon Mun Islands (Vietnam), for which people were willing to pay US$1.79/visit (Pham & Tran Citation2004). In this regard, future results should verify these findings. Our study relates to a national park which is known for its nature, landscape, and biodiversity value, whereas Pham & Tran (Citation2004) considered the Hon Mun Islands, which are located in Nha Trang City, one of the most beautiful coastal cities in Vietnam famous for its coral reefs and diving. In addition, the survey for the Hon Mun Islands was administered to tourists with high preference for coral reefs and recreational value.

Another WTP question addressed the respondents’ preferences for protecting O. tamdaoensis. The results for the single-bounded model show that people were willing to pay a mean of VND17,567 (US$0.81), whereas the WTP from the double-bounded model was VND21,571 (US$1.0) (). These WTP values were lower than the pre-survey results, which may be due to the respondents’ education level and income. As in the case of WTP for conserving the ecosystem, the estimated mean WTP in the double-bounded model was higher than that in the single-bounded model. This suggests that if people are given different bids then their WTP decisions may change.

Table 5. Estimation results for WTP for protecting Opisthotropis tamdaoensis (in US$).

This study's WTP result is low but still higher than that for protecting wild elephants in Sri Lanka at US$0.25 (Bandara & Tisdell Citation2004). In Vietnam, the respondents’ WTP based on Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City for protecting Vietnamese rhinos was US$2.5/household (Truong Citation2007). Therefore, it is not easy to compare these two studies because of the difference in unit of analysis.

shows the correlations between demographic characteristics and the level of WTP. The results show significant correlations between the education level and the level of WTP both for conserving the ecosystem and for protecting O. tamdaoensis. In the case of WTP for O. tamdaoensis, monthly income showed highly significant correlations.

Table 6. Correlations between WTP and demographic variables.

The logit model was employed to test the effects of various economic and social factors on WTP for biodiversity at Tam Dao National Park. In three subsamples with three average bids, there were differences across those factors influencing WTP. For the lowest average bid (VND28,000), the education level had a significant effect on WTP at the 10% level. The coefficient of the education level was positive, indicating that the respondents with higher education levels reported higher WTP values for conserving the ecosystem at Tam Dao National Park (). This result is consistent with the findings of Dang & Nguyen (Citation2009), who reported that people with more education were more likely to pay attention to the environment and more willing to contribute to preservation funds.

Table 7. Results of the logit regression model for three subsamples.

For the given bid of VND35,000, no economic and social factors had significant effects on WTP (). According to the results, gender had a negative effect on WTP, and female respondents had higher preferences for biodiversity. By contrast, Nuva et al. (Citation2009) employed a logit regression model and showed that male visitors were willing to pay a bid price 1.775 times higher than that of female visitors. Thus in the study of Nuva et al., Indonesian male respondents revealed a higher willingness to pay, while in this study Vietnamese female respondents are willing to pay more. This can be explained by higher gender equality and income independence of the women in Vietnam. In Vietnam, women today are strongly empowered, financially independent, and highly educated. In most households, women manage household income, including daily expenses. This study's survey was conducted in Hanoi, a city with a high level of gender equality and women with a strong voice and high income.

Noteworthy is that, for the given bid of VND42,000, the logit model results show that education level and income had significant positive effects on WTP for conserving the ecosystem at Tam Dao National Park at the 95% confidence interval. The coefficients of the education level and income were positive (1.109 and 1.086, respectively), indicating that those respondents with higher education levels and income were willing to pay more for ecosystem conservation at Tam Dao National Park.

From the results for the three subsamples, it can be concluded that various economic and social factors had no impact on WTP for conserving the ecosystem at Tam Dao National Park. However, for the highest bid, the respondents’ education level and monthly income had a significant effect on WTP. Therefore, for a low admission fee, the respondents were not concerned about their decision to pay additional money to visit the national park. However, for a high admission fee, the respondents’ decision was affected by their education level as well as by their income. This suggests that income has a positive effect on people's preferences in various preservation issues. Nuva et al. (Citation2009) and Yoeu & Pabuayon (Citation2011) also found income to be positively related to WTP for each individual.

Conclusions

In this paper, by using the hypothetical market, we investigated the monetary value of biodiversity and analyzed people's perception and preference for biodiversity conservation. In addition, we identified which socioeconomic factors have a significant influence on the WTP of individuals for conserving biodiversity in Vietnam.

The mean WTP values estimated in the single-bounded model for conserving the ecosystem and protecting O. tamdaoensis were VND28,562 (US$1.32) and VND17,567 (US$0.81), respectively. The mean WTP values estimated in the double-bounded model were VND35,250 (US$1.63) and VND21,571 (US$1), respectively. In 2013, the total visits to Vinh Phuc Province were more than one million, at this rate, and the total value stated by the public amounted to approximately US$1.63 million/year for biodiversity conservation (c. VND35.045 billion) and US$1 million for O.tamdaoensis protection (c. VND21.5 billion).

In this study, the WTP for O. tamdaoensis is lower than that for biodiversity conservation. In Vietnam, O. tamdaoensis is not a well-known species and its value has not been elicited to the public yet. According to Nishizawa et al. (Citation2006), after respondents became familiar with the goods/services, they were more willing to pay for the policy that supports the protection of these goods/services than when they were ignorant about them. Thus, disseminating information and promoting environmental education would contribute to increasing the WTP of individuals for the target species O. tamdaoensis, by improving the public's awareness of the importance of the species.

Based on the findings, policy makers would be able to develop a protection program for biodiversity conservation. Involving park visitors in conservation policies at Tam Dao and other national parks in Vietnam may lead to better outcomes. The results indicate that people have strong preferences for biodiversity values and nature conservation in Vietnam. The results might provide a rationale to raise the admission fee at Tam Dao National Park because people are willing to pay some additional money to protect biodiversity at the site. Collected entrance fees can be managed through an associated fund under the control of community members. If visitors have more confidence in the effectiveness of the program for biodiversity conservation, the WTP for biodiversity conservation may increase (Nishizawa et al. Citation2006).

Many factors influenced people’s willingness to contribute to the preservation fund. In general, most wanted to protect the environment of Vietnam and preserve the park for use by future generations. People who were not willing to contribute to the fund believed that it was the government's responsibility to do so through tax revenues. Many did not even trust the organization handing the fund. In the logit regression, female respondents were willing to pay more than their male counterparts, and WTP was positively affected by monthly income and the education level at the 95% confidence level. In addition, the results for a high admission fee indicate that the respondents’ WTP was positively influenced by their education level and monthly income. This finding is consistent with previous studies; that WTP is determined by income (Truong Citation2007; Dang & Nguyen Citation2009; Nuva et al. Citation2009; Yoeu & Pabuayon Citation2011; Tran & Bui Citation2013). This suggests future studies to investigate the relationship between non-market services from biodiversity and income by imperially applying elasticity or an inverted U-shaped curve (Ahmed et al. Citation2007).

This study has some limitations. The analysis focused only on preferences for biodiversity value for tourism, and the survey was conducted in a large city (Hanoi). In addition, the total value of biodiversity at Tam Dao National Park was not determined to compare annual benefits and costs for the economic viability of tourism and biodiversity conservation at the park. Further, this study did not test other payment vehicles to examine the effectiveness of CVM approaches in the Vietnamese context.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Ahmed M, Umali GM, Chong CK, Rull MF, Garcia MC. 2007. Valuing recreational and conservation benefits of coral reefs – the case of Bolinao, Philippines. Ocean Coast Manag. 50:103–118.

- Akcura E. 2015. Mandatory versus voluntary payment for green electricity. Ecol Econ. 116:84–94.

- Asafu-Adjayea J, Tapsuwan S. 2008. A contingent valuation study of scuba diving benefits: case study in Mu Ko Similan Marine National Park, Thailand. Tour Manag. 29:1122–1130.

- Bandara R, Tisdell C. 2004. The net benefit of saving the Asian elephant: a policy and contingent valuation study. Ecol Econ. 48(1):93–107.

- Christie M, Fazey I, Cooper R, Hyde T, Kenter JO. 2012. An evaluation of monetary and non-monetary techniques for assessing the importance of biodiversity and ecosystem services to people in countries with developing economies. Ecol Econ. 83:67–78.

- Costanza R, de Groot R, Sutton P, van der Ploeg S, Anderson SJ, Kubiszewski I, Farber S, Turner RK. 2014. Changes in the global value of ecosystem services. Glob Environ Change. 26:152–158.

- Dang LH, Nguyen TYL. 2009. Willingness to pay for the preservation of Lo Go-Xa Mat National Park (Tay Ninh Province) in Vietnam. Economy and Environment Program for Southeast Asia (EEPSEA).

- De Groot R, Brander L, Van Der Ploeg S, Costanza R, Bernard F, Braat L, Christie M, Crossman N, Ghermandi A, Hein L, et al. 2012. Global estimates of the value of ecosystems and their services in monetary units. Ecosyst Serv. 1(1):50–61.

- Do TN, Bennett J. 2007. Willingness to pay for wetland improvement in Vietnam's Mekong River Delta. Paper presented at: Australian Agricultural and Resource Economics Society. 51st AARES Annual Conference; Queenstown, New Zealand.

- Engel S, Pagiola S, Wunder S. 2008. Designing payments for environmental services in theory and practice: an overview of the issues. Ecol Econ. 65(4):663–674.

- Indab AL. 2007. Willingness to pay for whale shark conservation in Sorsogon, Philippines. Philippines: Economy and Environment Program for Southeast Asia.

- Jenkins M, Scherr SJ, Inbar M. 2004. Markets for biodiversity services: potential roles and challenges. Environ Sci Policy Sustain Dev. 46(6):32–42.

- Ji IB, Kwon OS, Song WJ, Kim JN, Lee YG. 2013. Estimating willingness to pay for livestock industry support policies to solve livestock's externality problems in Korea. J Rural Dev. 37:97–116.

- Lafta T. 2013. Attitudes towards nuclear power in Sweden: a study to elicit the willingness to pay [dissertation]. Stockholm: Lulea University of Technology Economic Unit.

- Lee CK, Mjelde WJ. 2007. Valuation of ecotourism resources using a contingent valuation method: the case of the Korean DMZ. Ecol Econ. 63:511–520.

- Mace GM, Norris K, Fitter AH. 2012. Biodiversity and ecosystem services: a multilayered relationship. Trends Ecol Evol. 27(1):19–26.

- Nelson E, Mendoza G, Regetz J, Polasky S, Tallis H, Cameron D, Shaw M. 2009. Modeling multiple ecosystem services, biodiversity conservation, commodity production, and tradeoffs at landscape scales. Front Ecol Environ. 7(1):4–11.

- Nguyen TH, Tran DT. 1999. Using the travel cost method to evaluate the tourism benefits of Cuc Phuong National Park. In: Francisco H, Glover D, editors. Economy and Environment: Case studies in Vietnam. Singapore: International Development Research Centre; p. 129–145.

- Nishizawa E, Kurokawa T, Yabe M. 2006. Policies and resident's willingness to pay for restoring the ecosystem damaged by alien fish in Lake Biwa, Japan. Environ. Sci. Policy. 9(5):448–456.

- Nuva R, Shamsudin MN, Radam A, Shuib A. 2009. Willingness to pay towards the conservation of ecotourism resources at Gunung Gede Pangrango National Park, West Java, Indonesia. J Sustain Dev. 2:173–186.

- Pham KN, Tran VHS. 2004. Recreational value of the coral surrounding the Hon Mun islands in Vietnam: a travel cost and contingent valuation study. World Fish Center. Economic Valuation and Policy Priorities for Sustainable Management of Coral Reefs. 84–103.

- Primack RB. 2006. Essentials of conservation biology (Vol. 23). Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates.

- Tong C, Feagin RA, Lu J, Zhang X, Zhu X, Wang W, He W. 2007. Ecosystem service values and restoration in the urban Sanyang wetland of Wenzhou, China. Ecol Eng. 29(3):249–258.

- Tran HT, Bui DT. 2013. Asian Cities Climate Resilience Working Paper Series 4: Cost–benefit analysis of mangrove restoration in Thi Nai Lagoon, Quy Nhon City, Vietnam. London: International Institute for Environment and Development.

- Truong DT. 2007. WTP for conservation of Vietnamese rhino. Singapore: Economy and Environment Program for Southeast Asia.

- Turner WR, Brandon K, Brooks TM, Costanza R, Da Fonseca GA, Portela R. 2007. Global conservation of biodiversity and ecosystem services. BioScience. 57(10):868–873.

- Tyrväinen L, Väänänen H. 1998. The economic value of urban forest amenities: an application of the contingent valuation method. Landsc Urban Plan. 43(1):105–118.

- Udomsak S. 2003. Economic valuation of coral reefs at Phi Phi Islands, Thailand. Int J Glob Environ Issues. 3(1):104–114.

- Yoeu A, Pabuayon IM. 2011. Willingness to pay for the conservation of flooded forest in the Tonle Sap Biosphere Reserve, Cambodia. Int J Environ Rural Dev. 2(2):1–5.