ABSTRACT

Extensive evidence exists on how characteristics and circumstances of children shape their lifepaths and outcomes, and on the scale of resulting need. However, little research exists assessing the numbers of children who may be at risk of harm or disadvantage due to their immigration status. In this paper, we sought to establish the degree to which it is possible to monitor the aggregate vulnerability to risk of children in the UK by virtue of immigration status. First, we developed an observable set of immigration risk and vulnerability factors through workshop consultations that were analysed to produce a core set of variables that might be measured to assess aggregate need by virtue of immigration status. Second, we assessed through an administrative data review what is known statistically about the numbers of children at risk by virtue of immigration status in the UK. This research indicates a considerable gap in statistical knowledge of the level of vulnerability of children in the UK by virtue of immigration status. The approach we have developed provides a framework for future statistical work that might address this gap.

KEYWORDS:

1. Introduction

This paper describes an attempt to estimate the number of children in the UK who may be vulnerable to risk of harm or disadvantage by virtue of immigration status. The starting point is the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) which entered into force as international law on 2 September 1990 (UN General Assembly, Citation1989). S.55 of the Borders, Citizenship and Immigration Act 2009 gave the Secretary of State responsibility for ensuring that functions in relation to immigration, asylum or nationality are ‘discharged having regard to the need to safeguard and promote the welfare of children who are in the United Kingdom.’ The goal of the work reported here was to develop a framework that would provide a broad purview of the full range of risks and experiences of children resulting from immigration status, not limited to refugee children but to develop a more general framework for monitoring concerns for the whole range of types of insecure immigration status.

The aim of the work reported here was: 1) to develop an observable set of immigration risk factors that could be used to assess the aggregate number of children affected, and; 2) to describe what is known statistically about the numbers of children at risk in the UK. The review of statistics generates substantive findings, but the primary purpose was to assess the quality of current statistical knowledge in the UK for understanding aggregate risk to children.

Ultimately, it is important to know not just numbers of children affected but also their characteristics, outcomes, experience and to know what support they receive. Important outcomes include child-focused care outcomes, family outcomes, and child and family rights, as explained in Holmes, La Valle, Hart, and Pinto (Citation2019). There are important related studies on the outcomes of unaccompanied asylum-seeking children (UASC) in the UK (Chase, Citation2010; Coyle & Bennet, Citation2016; Kohli, Citation2006; O’Higgins, Citation2018). The framework developed here could be useful in integrating research concerning different forms of risk related to immigration status or addressing different questions such as outcomes or experiences in a coherent way. However, the primary purpose of this paper is to put forward a set of basic immigration status categories that our analysis suggests are essential to understanding aggregate risk, and to test the capacity of UK statistics for understanding the numbers of children affected.

This requires a framework of definition of this form of vulnerability and research in available statistics to assess what is currently measured. We show that the UK does not have any framework for understanding this type of need. There is a wide multi-disciplinary literature on how characteristics and circumstances of children shape lifepaths and outcomes (Heckman & Mosso, Citation2014; Joshi, Citation2020; Marmot, Citation2010). This evidence has at times had a major impact on social policy in the UK (Cabinet Office, Citation2011; HM Treasury, Citation2003). However, disadvantage resulting from immigration status is rarely included in these analyses. Immigration Acts 2014 and 2016 introduced so-called ‘hostile environment’ policies which increase the vulnerability of children without immigration status and restrict the rights of those with impermanent status (Equality and Human Rights Commission, Citation2020; Qureshi, Morris, & Mort, Citation2020). After a decade of crisis in immigration, with growing numbers of children affected and politicisation of issues of immigration it seems to us essential to have a good grip on the numbers of children affected and how these forms of vulnerability play out in outcomes and experiences. The experience by children of mistreatment within the immigration system (HM Inspectorate of Prisons, Citation2020) or while awaiting decisions of courts (Gill et al., Citation2020) are important examples of why a humane society would have concern to understand the scale and nature of harm experienced by children because of issues of immigration status. This paper concerns the attempt to estimate numbers, because if we cannot estimate the number of children influenced it is clearly not possible to consider outcomes or experiences in a representative way. By focusing on the number of children we test the capacity of the existing statistical systems in the UK to reflect the duty of care of government and society to these children.

The paper starts with a brief description of the approach and then reports the results of workshop consultations with key experts on child migration that led to the construction of four risk categories. The paper then presents findings from an administrative data review to display what is known statistically about the number of children with different immigration status. The discussion draws out the implications for research, practice and policy of social care and child welfare in the UK.

2. Theoretical underpinnings

We emphasise the need to hold quantitative and statistical information alongside qualitative and case-level information in ways that enable each to play a scientifically rigorous role in social policy formation and evaluation (Burch & Heinrich, Citation2016; Engeli & Allison, Citation2014). Ultimately, practice and policy require a focus on the child, and it is important to bear in mind that single variables can only tell us so much about the experiences of people (Molenaar, Citation2004; von Eye, Bergman, & Hsieh, Citation2015). We also note the finding of a Children’s Commissioner’s Office (CCO) report (Citation2017) on the subjective wellbeing of children subject to immigration control in England:

Children’s recollections of their experiences within the UK immigration system were largely negative; they perceived the system as adversarial, confusing and stressful, with few exceptions. Several children described having a positive initial experience of being received by law enforcement or border agents in the UK, particularly in comparison to other country contexts: “[they treated me] much better than I would have expected … I was very scared when I was in the lorry and when the policeman opened the door but he was smiling a lot at me and I’m sure he said ‘welcome to England’” … This feeling of being welcomed and supported was often short lived, however, with the majority of young people describing the process as overwhelmingly hostile, inaccessible and difficult to understand. (p. 11)

2.1. Understanding risk

Risk and protective factors exist as characteristics of person and environments and are associated with positive or negative child-level outcomes. Factors of risk and of protection can function differently in accordance with the child’s ecological context (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1977, Citation1986). Risk can be classified as proximal, directly experienced by the child, or distal, existing in the child’s ecological context (Wright, Masten, & Narayan, Citation2012). Protection is further subclassified as protective when it improves outcomes in the context of a high probability of poor outcomes or promotive when it improves outcomes as all levels of probability of poor outcomes (Luthar, Sawyer, & Brown, Citation2006; Sameroff, Citation2000). Moderation and mediation describe the nature of effects of risk factors on child-level outcomes (Baron & Kenny, Citation1986). Moderation is said to occur when a risk factor directly affects the direction and/or strength of the relationship between another characteristic and the outcome, also called an interaction effect. Mediation is when a risk factor explains or is hypothesised to be the pathway for the relationship between another characteristic and an outcome.

Critical literature on risk and resilience reaffirms that risk should not be conceptualised as an internal characteristic attribute of the child (Masten, Citation2014). As such, this paper relates the child’s immigration status closely to characteristics of their immediate ecosystem (household, family) shaped by the wider macro-system, and concerns an interaction of the child with the wider ecosystem (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1977, Citation1986; Luthar & Cicchetti, Citation2000). We must understand not just the outcomes and experiences of children by immigration status, but also how vulnerability to harm and disadvantage by virtue of their immigration status interacts with other forms of vulnerability, need and risk.

3. Methods

The research draws upon three workshop consultations with key experts on child migrants in the UK, followed by a review of child-related and migration-related UK administrative data. First, workshop consultations were carried out with key experts and agencies in Autumn 2019 to identify the most common issues of concern experienced by children by virtue of immigration status in the UK. This initial meeting was hosted by the CCO with invited participation from 15 experts in total, including four from the CCO, three from academic institutions, four from UK government departments, and four from practice institutions. Participants were chosen as known experts in the field, or those who had lobbied the CCO on related issues of concern. We intended that this group would be large and reasonably representative of the knowledge in the sector in relation to issues of concern by virtue of immigration status. We asked the participants to list the paramount issues of concern to them in relation to the risks to harm or disadvantage of children by virtue of immigration status. This led to a long list of themes ( below) very familiar to those campaigning for the rights of children. This was followed up with two further workshops with smaller subgroups of the original group to reshape the long list of issues into a set of risk categories that fit within a clear methodological framework of risk and distinguish categories of risk concerning immigration status itself from other issues such as poverty or experience of the criminal justice system. We set the following methodological ground rules for identifying the immigration risk categories: 1) they span the list of issues of concern (mutually exhaustive) so that all these and other missing or emerging issues can be included; 2) they are inclusive of and intersecting with most vulnerable groups of children in the UK; and, 3) they are parsimonious. To achieve precision, risk categories were required to be as specific and narrow as possible. They were allowed to have further nested sub-categories, and the categories were not required to be mutually exclusive. It was important to disentangle specific types of issues to achieve parsimony.

Table 1. Groups of vulnerable children in the UK by virtue of their immigration status.

Second, using the risk categories identified, we undertook an exhaustive scoping review of administrative data resources published by the Home Office, Department for Education, Office of National Statistics, Wales’s Statistical Directorate, Scotland's Children and Families Directorate, National Records of Scotland, Northern Ireland's Department of Health, and the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency. Datasets were screened for all data items relevant to the migration status and risks for children between 2010 and 2020. It is important to note that in 2020, the UK experienced the COVID-19 pandemic which saw border and travel restrictions as well as public and private services deemed as non-essential greatly reduced in response. The data review was undertaken at a time of extreme difficulty for vulnerable children and young people in the UK.

There are certain limitations to this research design. First, the voices of child migrants themselves are not represented in this study. Second, findings from the workshop consultations and the data review cannot be said to reflect all possible subgroups or issues of concern in relation to children vulnerable by virtue of immigration status. Other participants might have identified other issues and new issues will always emerge. However, we have since shared the long list with three further academic experts and no further issues have been identified that would change the analysis. Therefore, we have good reason to think we have achieved saturation, in identifying a core set of categories that underpin concerns about children by virtue of immigration status and that should be measured by a society with concern for these children. The analysis conducted identified a set of underpinning concepts that provide a stable framework for conceptualising need by virtue of immigration status. Thus, the paper can offer firm conclusions on where there are gaps in the measurement of aggregate vulnerability by virtue of immigration status and how these gaps may be addressed.

4. Conceptualising risk by immigration status

During our discussions with participants in the workshop consultations, a wide array of issues of concern were raised, leading to the construction of a longlist of groups of vulnerable children. The authors met over two further sessions with representatives of the CCO and academic participants to analyse the risks underpinning the items in the longlist of concerns in accordance with the three methodological rules. The following section describes the transition from the initial longlist of vulnerable children in the UK to a final set of four risk categories. This approach distinguishes a set of immigration status categories from other factors with which immigration status interacts to mediate and moderate risks of harm and disadvantage.

4.1. Child vulnerability in the UK by immigration status

The workshops established an initial longlist of groups of children in the UK vulnerable by virtue of their immigration status shown in .

In parsing the list of issues to identify underpinning risk factors, it became evident that the following elements must be distinguished in order to adequately span the issues listed: 1) Current status, or legal status as recognised in law in practice; 2) Entitlement, or legal status in principle due but not necessarily operationalised; 3) Context, comprising issues such as language, poverty and legal support that influence capacity to realise entitlement or maintain functioning; and 4) Legal processes, where the child is in the system and how legal processes are operating. When these features are clearly distinguished, it becomes possible to describe parsimoniously each of the groups of vulnerable children in the longlist and identify the underpinning risk categories.

There are children who have the right to remain in the UK yet do not have documents to prove it. It may be their birth right or a freestanding right. These children are not required to go through any legal process by which to register their entitlement to remain in the UK. Their right to reside in the UK is innate but they may not have evidence to prove it. In immigration law terms, no grant of leave is needed here, merely recognition of a pre-existing right to reside. Many are unaware of the need for this recognition. Lack of any such recognition leaves these children vulnerable to removal from the UK and adverse treatment within the hostile environment. Thus, their right and entitlement is not recognised in practice.

A child born today in the UK to a British parent is British. Nothing needs to be done for that child to become British. The Passport Office will require evidence of the child’s right to British Citizenship by descent to issue a British passport. This is an administrative process which the child needs to go through to obtain a document which evidences their British nationality. To prove their nationality, the child would need access to evidence of their paternity, parents’ nationality, and their place of birth. Many vulnerable children, such as those in care, may not have access to these documents.

This principle lies behind the Windrush scandal where Commonwealth migrants with permanent residence rights in the UK since 1973 had been wrongly detained, deported and denied legal rights due to not having access to documentation. S.1(2) of the Immigration Act 1971 entitles Commonwealth citizens already present and settled in the UK when the act came into force on 1 January 1973 to stay indefinitely in the UK. Children of the Windrush Generation who arrived in the UK from Caribbean countries before 1 January 1973 and remained since then, are in the UK legally. Many have acquired British citizenship, or otherwise had documentation confirming their status in the UK. Some, however, do not. For individuals in these circumstances, they must undertake a highly bureaucratised process to apply for confirmation of their status by the Home Office. Nevertheless, in the context of hostile environment policies, lack of access to documentation resulted in their legal rights being disregarded (Williams, Citation2020).

4.2. Risk categories of immigration status in the UK

We identified four specific risk categories of immigration status, shown in , with decreasing average risk of harm and disadvantage.

Table 2. Four risk categories of children by virtue of immigration status.

These four categories might be thought to reflect a latent, non-linear continuum of permanence of status. This is non-linear because indefinite leave to remain grants the holder permanent residency in the UK which is a much more permanent and secure status than limited leave to remain, which grants the holder temporary residency in the UK. Indefinite leave to remain is less secure than citizenship as it can be revoked and provides fewer rights for intergenerational transfer of status.

4.2.1. Issues that moderate the legal process in seeking permanent status

We include here items from the longlist that moderate the legal process in seeking permanency. In other words, items that influence the probability for a child with non-permanent status of advancing towards permanency. Examples of these items from the longlist are false documentation, no documentation, no formal immigration status, age-disputed children, children of dual nationality, children not entitled to legal aid, children receiving poor legal advice, and stateless children. For example, age dispute or absence of documentation will limit the likelihood of realisation of permanent status. The issue is a concern about the likelihood of the achievement of permanency for a child or young person without more permanent status, and of what the experiences and outcomes for such children and young people might be.

We also include here issues that compound the risk of failing to realise more permanent immigration status and increase the likelihood of enforcement action. Examples of these items from the longlist are children of non-permanent status who offend, missing foreign national children, non-UK national children in care, trafficked children or children in abusive situations, and children not on spousal visa whose parent has additional vulnerability (e.g. domestic abuse). For example, the issues noted of missing foreign national children and non-UK national children in care each reflect the combination of a potential temporary immigration status and a wider risk factor for the child.

4.2.2. Impact of immigration status on risk of harm and disadvantage

We include here children without recourse to public funds and children whose parents become British but they themselves do not. Children in families with limited leave to remain are unlikely to have recourse to public funds. Lack of status restricts access to secondary healthcare, access to education, housing, ability to open bank accounts, driving and leaves children vulnerable to adverse treatment from law enforcement and raids on private property. This has implications for the experience of children and heightens risk of both harm and disadvantage due to poverty for children in families without other sources of income.

4.2.3. Post-removal risk

The issue of removed looked after children was raised in the workshops, suggestingthat too many local authorities do not fully appreciate their legal obligations to a child once the child is placed in the care of someone in another country and that there are very large discrepancies in practice. This specific issue is not only an important example of a risk resulting from immigration status for the specific subgroup of children who are in care and placed abroad but is also indicative of the general issue of risk resulting after a legal process leads to removal, deportation or departure from the UK, and a ban of re-entry for up to 10 years.

5. Measuring risk by immigration status

A data review was undertaken to assess the degree to which it is possible to accurately estimate the actual number of children in each category based on current available UK administrative data. We found that it is not possible to estimate from the official statistics the number of children with any accuracy because the administrative data follows administrative processes rather than people and so in technical terms measures flows, rather than stocks. Moreover, many children may be missing from the official statistics, namely undocumented children and children who are ‘invisible’ to the system, or below the radar (Chase, Citation2010; Kohli, Citation2006). However, there are important subgroups on which data are available that provide partial indicators of the number of children in the different risk categories of immigration status.

5.1. Children with no leave to remain

We have identified data on three subgroups of children likely not to have leave to remain status, namely asylum-seeking children with initial applications pending, children in immigration detention and returned children. The numbers in these different groups cannot be added up to give a meaningful total because of double counting as children move between these categories. The total number of children (stock) in the population without leave to remain cannot be known without tracking the movement (flow) of children as they move between different statuses and outcomes. These different stages of legal processes are not tracked and identified in the available data. The number of children with asylum applications in the UK only relate to the initial application for asylum. This excludes applications to upgrade a grant of humanitarian protection or discretionary leave to refugee status (i.e. a grant of asylum) and for further extensions of stay.

5.1.1. Asylum-seeking children

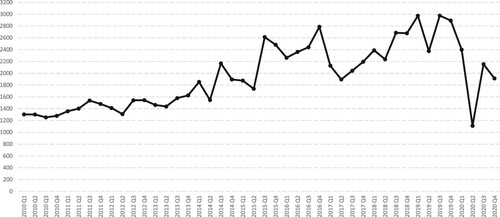

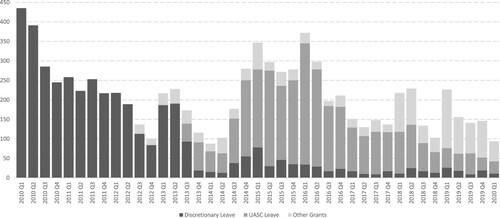

The number of asylum applications pending provides an important indicator of the number of children with no leave to remain. shows a rising trend in child asylum applications (Home Office, Citation2021), more than doubling between 2010 in 2019, with a pronounced drop in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 1. Quarterly flow of children with asylum applications in the UK Source: Home Office, Citation2021.

In 2020, 7,577 children in the UK had asylum applications pending, rendering them at that time with no leave, a significant reduction from 2019 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This number includes 2,229 Unaccompanied Asylum Seeking Children (UASC), who are under 18 and do not have any parent or responsible older adult to look after them (Home Office, Citation2016a; UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, Citation2005). The number also includes 420 Stateless children, who are under 18 and not considered as nationals by any state under the operation of its law (UN General Assembly, 1954, 1961; Home Office, Citation2016b). They are entitled to make a statelessness application.

5.1.2. Children in immigration detention

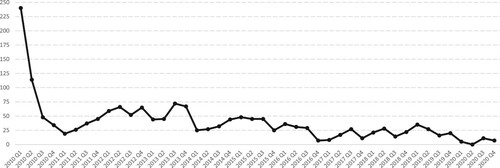

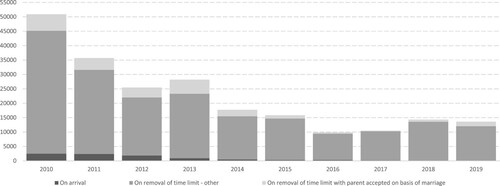

Children in immigration detention also have no leave to remain. Beginning with a huge drop in 2010, shows a slowly decreasing trend in immigration detention for children (Home Office, Citation2021).

Figure 2. Quarterly flow of children entering immigration detention in the UK Source: Home Office, Citation2021.

In 2020, 23 children were recorded as entering detention, with 22 children recorded as leaving detention, and 18 children leaving 3 days or fewer after entry, and 4 children leaving 4–7 days after entry. The total number is uniquely low in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, with the prior year seeing 98 children entering detention and 101 children leaving. Given reports of poor child safeguarding in detention facilities and the misplacement of children in adult detention centres (HM Inspectorate of Prisons, Citation2020), the presence of children in immigration detention is a major cause for concern.

5.1.3. Returned children

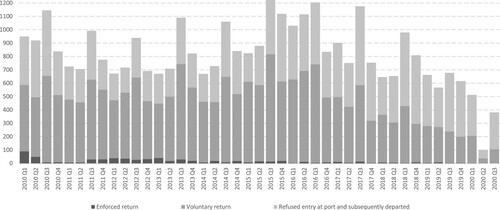

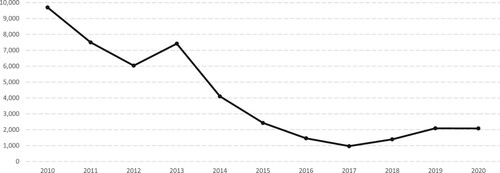

Being returned is another indicator of children with no leave to remain. reports shows a slowly decreasing trend in returned children since 2010, attributable to an increase in refused entry at port followed by subsequent departure since 2015 (Home Office, Citation2021).

Figure 3. Quarterly flow of children returned from the UK Source: Home Office, Citation2021.

Returned children are highly vulnerable to post-removal risk. In 2020, 994 children were returned from the UK. Of those, 346 children returned voluntarily, 1 child returned forcibly, and 647 children were refused entry at port and subsequently departed. The total number is low in 2020., In 2019, 2,523 children were returned. Vulnerable groups such as undocumented child migrants continue to perceive the spectre of being detained or deported as a threat, pushing them to hide from authorities (Chase, Citation2010; Kohli, Citation2006). Moreover, it is not possible to identify an aggregate using detention data and return data because it cannot be determined whether these numbers overlap over the same reporting period.

5.2. Children with limited leave to remain

We have identified three subgroups of children likely to have limited leave to remain status, namely refugee children, children with other limited leave (such as Discretionary Leave, or UASC Leave), and UASCs who are looked after. Again, these numbers cannot be added up meaningfully because of double counting. For example, a UASC looked after may also be granted UASC leave.

5.2.1. Refugee children

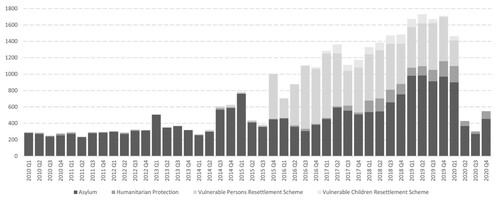

Refugee status entitles the child to limited leave to remain of five years, as per the UK immigration rules part 11 on asylum (Home Office, Citation2016a) and, in the case of stateless children, as per the UK immigration rules part 14 on stateless children (Home Office, Citation2016b). shows that the number of children granted refugee status in the UK was on a rising trend from 2010 to 2020 (Home Office, Citation2021), mostly attributable to resettlement schemes from outside the UK. Asylum and humanitarian protection for children inside the UK remained low despite the large numbers of child asylum applications.

Figure 4. Quarterly flow of children granted refugee status with five years limited leave Source: Home Office, Citation2021.

In 2020, 6,576 children were granted refugee status in the UK. This number can be divided into two groups. The first are asylum-seeking children in the UK, comprising 3,761 children granted asylum and 642 children granted humanitarian protection. The second group are resettled refugee children, comprising 316 children resettled under the Vulnerable Persons Resettlement Scheme and 52 children resettled under the Vulnerable Children Resettlement Scheme (Home Office, Citation2021; Wilkins & Sturge, Citation2020). Additionally, the Home Office releases quarterly and annual statistics on family reunion visa grants, entry clearance visas granted to family members of persons previously granted asylum or humanitarian protection in the UK, which entitle refugee status upon arrival with five years limited leave. In 2020, 2,992 children, 88 of whom were stateless, were granted such visas. However, we found no available statistics on whether these visa recipients successfully arrived in the UK.

5.2.2. Children with other limited leave

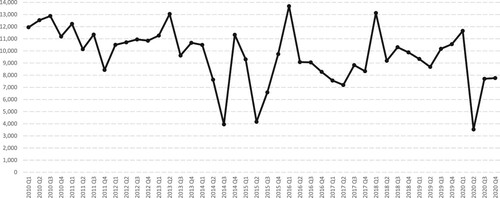

Not all asylum-seeking children are granted refugee status. However, on a case-by-case basis, these children are not returned immediately. Instead, these children, mainly UASCs, are granted other forms of limited leave to remain with varying durations. shows that the number of children granted other forms of limited leave has fluctuated overtime (Home Office, Citation2021), with big increases between 2014 and 2016, coinciding with large influxes of refugees to Europe (Crawley, Düvell, Jones, McMahon, & Sigona, Citation2017).

Figure 5. Quarterly flow of children granted other limited leave Source: Home Office, Citation2021.

In 2020, 278 children were granted other forms of limited leave. This group includes 45 children granted discretionary leave, which entitles limited leave of no more than 30 months, 64 children granted UASC leave, which entitles limited leave of 30 months or until the child turns 17.5 years old, whichever is shorter, and 169 children granted alternative forms of leave such as family and private life rules, leave outside the rules, Calais leave, and exceptional leave to remain, which entitle limited leave of varying durations. Children with other forms of limited leave may have an opportunity through appeals processes to obtain refugee status (Home Office, Citation2016a). However, children experiencing the asylum appeals process are often at an increased risk of experiencing confusion, anxiety, mistrust, disrespect, communication difficulties, and distraction (Gill et al., Citation2020). At the end, if they are still unable to gain refugee status, these children are removed from the UK upon expiry of their limited leave to remain.

5.2.3. Unaccompanied asylum-seeking children

One key administrative resource for estimating the number of UASC children with limited leave to remain in the UK is the Children Looked After statistics from England and Wales (Department of Education, Citation2020; StatsWales, Citation2021), which provides a source at child-level rather than at application-level. Looked after UASC are also holders of limited leave. This gives the number of looked after UASCs in 2020 as 5,000 children in England and 80 children in Wales. The data for England includes estimated category of need, with 4,360 categorised as having experienced ‘absent parenting’, 390 with ‘abuse or neglect’, 170 with ‘family in acute stress’, 50 with ‘family dysfunction’, and 30 with ‘low income’, as of 2020. Published statistics for Scotland and Northern Ireland do not separate out UASCs from children looked after numbers.

5.3. Children with indefinite leave to remain

In 2020, 13,628 children were granted indefinite leave to remain (Home Office, Citation2021). This includes children granted indefinite leave to remain after having been in the UK for five years with limited leave to remain and holding a residence card as a refugee or person with humanitarian protection. shows the number of children granted indefinite leave to remain in 2019 fell to less than a third of what it once was in 2010. Separately, only 29 refugee children outside the UK were granted resettlement with indefinite leave through the Gateway Protection Programme in 2020, the lowest number in the last ten years due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 6. Annual flow of children granted indefinite leave to remain Source: Home Office, Citation2021.

also shows that in 2020 the number of children granted indefinite leave under family formation and reunion fell to a fifth of what it was in 2010. In 2020, 2,084 children outside the UK were granted indefinite leave to remain under family formation and reunion as dependents joining British citizens or persons previously granted settlement in the UK. However, it is not known whether these visa recipients successfully arrived in the UK. The decreasing trend in the number of children with indefinite leave reflects a reduction in transition from having limited leave to obtaining indefinite leave.

Figure 7. Annual flow of children granted indefinite leave under family formation and reunion Source: Home Office, Citation2021.

5.4. Children with fully recognised UK citizenship

In 2020, 30,656 children were granted British citizenship (Home Office, Citation2021), a decrease from 38,758 in 2019. As above, this number does not provide a measure of the aggregate population of children with British citizenship in the UK, as the available administrative data captures flow from other statuses, and not general population change. Despite the large presence of children with limited and indefinite leave to remain in the UK as shown earlier, shows considerable fluctuation.

Figure 8. Quarterly flow of children granted British citizenship Source: Home Office, Citation2021.

6. The need for better information on vulnerable children by immigration status

In this paper we sought to establish the degree to which it is possible to monitor the aggregate risk and vulnerability of children in the UK by virtue of immigration status. Through workshop consultations and further analysis, we found that it is straight-forward to establish risk categories of immigration status into which children might be classified in a framework for assessing risk. The administrative data review established what is already commonly known but rarely interrogated, there is very little data that can estimate the number of children in the UK vulnerable by virtue of their immigration status. Despite the availability of administrative data on some subgroups within these categories of children, it is not possible to link them together as what is measured is the number of applications for permanency (flow) rather than the number of people seeking permanency (stock). The achievement of precision in those numbers is also highly unlikely in the future given the size of the population of undocumented children who were last estimated in the UK to range from 190,000–241,000 in 2017 (Jolly, Thomas, & Stanyer, Citation2020) and are driven to invisibility due to fear of detention and deportation (Chase, Citation2010; Kohli, Citation2006).

Nevertheless, the administrative data review did identify important findings. First, despite a rising trend in child asylum applications, more than doubling between 2010 in 2019, asylum and humanitarian protection for children inside the UK remained low, implying large numbers of asylum-seeking children in the UK. Second, the number of children granted indefinite leave to remain in 2019 fell to less than a third of what it was in 2010. Third, despite the considerable number of children with limited and indefinite leave to remain in the UK, there has been considerable fluctuation in the numbers of children granted UK citizenship since 2010. This suggests significant numbers of children stuck in insecure immigration status and highly vulnerable to the risk of harm and disadvantage by virtue of that immigration status.

It is for the Government of the UK to set immigration policy for the UK. However, there is clearly considerable progress that could be made in understanding the impacts of that policy both with more quantitative analysis across agencies and more use of administrative data alongside more and better dialogue with children, young people, families, and communities concerned. Short-term and longer-term outcomes and experiences mightbe obtained for some of the children vulnerable by virtue of immigration status if information were linked across administrative datasets (e.g. between Home Office and Department for Education for educational outcomes). Such data in aggregate, drawn from de-identified research information can enable research, policymaking, and professional practice to understand population sizes of children vulnerable by virtue of immigration status, forms of compounding risk (e.g. poverty and immigration status), outcomes, experiences, or degrees of risk. The authors support aspirations for enhanced data linkage capacities for children’s outcomes in the UK (House of Commons, Citation2008; House of Lords, Citation2008). We recognise this would require strong political will and a strong data-sharing culture across departments and levels of government. However, in considering the ethics of data collection and information gathering on children, it might be recognised that the benefits of aggregate data might outweigh the very tangible and personal risks that may result from information sharing without sufficient regards to the rights of the child. Aggregate data gathering should be carried out in ways sensitive to the complexity of these dangers and of the protections that are brought about through children’s ‘invisibility’ and silence about their own immigration statuses (Chase, Citation2010; Kohli, Citation2006).

There are urgent research questions about the experiences and outcomes of children known and unknown to the legal, health, education, welfare criminal justice, and child protection systems. In fact, even at a time of national crisis characterised by the COVID-19 pandemic when vulnerability levels are especially high, such information remains difficult to aggregate, greatly disadvantaging the capacities of social care and child welfare services. The starting point should be a more robust conceptualisation of risk by virtue of immigration status as being closely related to other characteristics of the child with the wider ecosystem (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1977, Citation1986; Luthar & Cicchetti, Citation2000), not as an internal characteristic of the child alone (Masten, Citation2014). The risk categories of immigration status conceptualised by the study have useful implications for research and professional practice in children’s rights, welfare, and social care in the UK. They are mutually exhaustive in explaining the issues of concern affecting children, and parsimonious in explaining the situation of the child with the fewest assumptions possible. This is evident in the data review in which we showed how groups of vulnerable children commonly perceived as homogenous (e.g. UASCs, refugee children, stateless children, etc.) in fact span the range of the different risk categories (No leave; Limited leave; Indefinite leave; UK citizenship). Researchers and practitioners can also employ the risk categories towards better understanding the legal entitlement and residence-related realities of children in the UK. Further qualitative or mixed-methods research and voice-related practice might be undertaken using the risk categories to capture the unique perceptions, perspectives, and experiences of children who are vulnerable by virtue of their immigration status in the UK.

Acknowledgements

This paper describes work supported in 2019 by the then Children’s Commissioner for England Anne Longfield. One of the authors carried out a data review as an employee of the Children’s Commissioner’s Office in 2019 and 2020 and the lead author was Director of Evidence in the Office when the work was initiated in 2019. The Commissioner has driven work on the issue of unmet or hidden need but is not an author on this paper and has not been given the opportunity to shape the findings or conclusions which are the independent views of the authors. We are very grateful to Julie Selwyn, Judy Sebba, Sonali Nag, Polly Vizard and participants in multiple workshops at the Children’s Commissioner’s Office for ideas, challenge and comments on drafts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Leon Feinstein

Leon Feinstein is Director of the Rees Centre and Professor of Education and Children's Social Care at the University of Oxford.

Yousef Khalifa Aleghfeli

Yousef Khalifa Aleghfeli is a Research Officer at the Rees Centre and DPhil Candidate at the Department of Education at the University of Oxford.

Charlotte Buckley

Charlotte Buckley is Head of Immigration at Just for Kids Law, focusing on the rights and welfare of migrants and victims of human and labour trafficking.

Rebecca Gilhooly

Rebecca Gilhooly is a Data Analyst and member of the Evidence team at the Office of the Children's Commissioner for England.

Ravi K. S. Kohli

Ravi K. S. Kohli is a Professor of Child Welfare at the Institute of Applied Social Research, University of Bedfordshire, and a qualified social worker.

Bibliography

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, 32(7), 513–531. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.32.7.513

- Burch, P., & Heinrich, C. J. (2016). Mixed methods for policy research and program evaluation. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Cabinet Office. (2011). Opening doors, breaking barriers: a strategy for social mobility. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/61964/opening-doors-breaking-barriers.pdf

- Chase, E. (2010). Agency and silence: Young people seeking asylum alone in the UK. British Journal of Social Work, 40(7), 2050–2068. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcp103

- Children’s Commissioner’s Office. (2017). Children’s Voices: A review of evidence on the subjective wellbeing of children subject to immigration control in England. https://www.childrenscommissioner.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Voices-Immigration-Control-1.pdf

- Coyle, R., & Bennet, S. (2016). Health Needs Assessment – Unaccompanied children seeking asylum. Kent Public Health Observatory. https://www.kpho.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/58088/Unaccompanied-children-HNA.pdf

- Crawley, H., Düvell, F., Jones, K., McMahon, S., & Sigona, N. (2017). Unravelling Europe’s ‘migration crisis’: Journeys over land and sea. Bristol, UK: Policy Press.

- Department of Education. (2020). Children looked after in England including adoption: 2019 to 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/children-looked-after-in-england-including-adoption-2019-to-2020

- Engeli, I., & Allison, C. R. (2014). Comparative policy studies: Conceptual and methodological challenges. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Equality and Human Rights Commission. (2020). Public Sector Equality Duty assessment of hostile environment policies. https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/sites/default/files/public-sector-equality-duty-assessment-of-hostile-environment-policies.pdf

- Gill, N., Allsopp, J., Burridge, A., Fisher, D., Griffiths, M., Hambly, J., … Schmid-Scott, A. (2020). Experiencing asylum appeal hearings: 34 ways to improve access to justice at first-tier tribunal. London and Exeter, UK: Public Law Project and University of Exeter. https://publiclawproject.org.uk/content/uploads/2020/12/201214_Asylum-Appeals_FINAL_pdf-for-publication.pdf.

- Heckman, J., & Mosso, S. (2014). The Economics of Human Development and Social Mobility (NBER Working Paper No. 19925). doi:https://doi.org/10.3386/w19925.

- HM Inspectorate of Prisons. (2020). Report on an unannounced inspection of the detention of migrants arriving in Dover in small boats. Detention facilities: Tug Haven, Kent Intake Unit, Frontier House, Yarl’s Wood and Lunar House. https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmiprisons/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2020/10/Dover-detention-facilities-web-2020_v2.pdf

- HM Treasury. (2003). Every Child Matters. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/272064/5860.pdf

- Holmes, L., La Valle, I., Hart, D., & Pinto, V. (2019). How do we know if children’s social care services make a difference? Developing an outcomes framework. London, UK: Nuffield Foundation. https://www.nuffieldfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/CSCS-Outcomes-Framework-July-2019.pdf.

- Home Office. (2016a). Immigration Rules part 11: asylum. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/immigration-rules/immigration-rules-part-11-asylum

- Home Office. (2016b). Immigration Rules part 14: stateless persons. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/immigration-rules/immigration-rules-part-14-stateless-persons

- Home Office. (2021). Immigration statistics, year ending December 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/immigration-statistics-year-ending-december-2020

- House of Commons. (2008). Treasury Committee. Counting the Population. Eleventh Report of Session 2007–08 (HC 1032). https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200708/cmselect/cmtreasy/1032/1032.pdf

- House of Lords. (2008). Select Committee on Economic Affairs. The Economic Impact of Immigration. First Report of Session 2007–08 (HL 82). https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld200708/ldselect/ldeconaf/82/82.pdf

- Jolly, A., Thomas, S., & Stanyer, J. (2020). London’s children and young people who are not British citizens: A profile. London, UK: Greater London Authority. https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/final_londons_children_and_young_people_who_are_not_british_citizens.pdf.

- Joshi, H. (2020). Pathways towards well-being. Longitudinal and Life Course Studies, 11(2), 153–155. doi:https://doi.org/10.1332/175795920X15809786476059

- Kohli, R. (2006). The sound of silence: Listening to what unaccompanied asylum-seeking children say and do not say. British Journal of Social Work, 36(5), 707–721. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bch305

- Luthar, S. S., & Cicchetti, D. (2000). The construct of resilience: Implications for interventions and social policies. Development and Psychopathology, 12(4), 857–885. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954579400004156

- Luthar, S. S., Sawyer, J. A., & Brown, P. J. (2006). Conceptual issues in studies of resilience: Past, present, and future research. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1094(1), 105–115. doi:https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1376.009

- Marmot, M. (2010). Health equity in england: The Marmot review 10 years On. London, UK: The Health Foundation. https://www.health.org.uk/publications/reports/the-marmot-review-10-years-on.

- Masten, A. S. (2014). Global perspectives on Resilience in children and youth. Child Development, 85(1), 6–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12205

- Molenaar, P. C. M. (2004). A manifesto on Psychology as idiographic science: Bringing the person back into scientific Psychology. This Time Forever. Measurement: Interdisciplinary Research and Perspective, 2(4), 201–218. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/s15366359mea0204_1

- O’Higgins, A. (2018). Analysis of care and education pathways of refugee and asylum-seeking children in care in england: Implications for social work. International Journal of Social Welfare, 28(1), 53–62. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsw.12324

- Qureshi, A., Morris, M., & Mort, L. (2020). Access denied: The human impact of the hostile environment. London, UK: Institute for Public Policy Research. https://www.ippr.org/files/2020-09/access-denied-hostile-environment-sept20.pdf.

- Sameroff, A. J. (2000). Developmental systems and psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology, 12(3), 297–312. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954579400003035

- StatsWales. (2021). Children looked after. https://statswales.gov.wales/Catalogue/Health-and-Social-Care/Social-Services/Childrens-Services/Children-Looked-After

- UN Committee on the Rights of the Child. (2005). General comment No. 6 (2005): Treatment of Unaccompanied and Separated Children Outside their Country of Origin. CRC/GC/2005/6. https://www.refworld.org/docid/42dd174b4.html

- UN General Assembly. (1989). Convention on the rights of the child. UN Treaty Series, 1577, 3. https://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6b38f0.html

- von Eye, A., Bergman, L. R., & Hsieh, C.-A. (2015). Person-Oriented methodological approaches. In R. Lerner (Ed.), Handbook of child Psychology and Developmental science (pp. 1–53). Hoboken, NJ, USA: Wiley. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118963418.childpsy121.

- Wilkins, H., & Sturge, G. (2020). Refugee Resettlement in the UK (House of Commons No. 8750). House of Commons. https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-8750/CBP-8750.pdf

- Williams, W. (2020). Windrush Lessons Learned Review: Independent review. Home Office. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/874022/6.5577_HO_Windrush_Lessons_Learned_Review_WEB_v2.pdf

- Wright, M. O., Masten, A. S., & Narayan, A. J. (2012). Resilience processes in development: Four waves of research on positive adaptation in the context of adversity. In S. Goldstein, & R. B. Brooks (Eds.), Handbook of resilience in children (pp. 15–37). New York, NY, USA: Springer. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-3661-4_2.