ABSTRACT

Built heritage forms a vital part of many cities’ building stock. It consists of historic buildings that are conserved for future generations because they are attributed with value. Despite this ascribed value, the conservation of heritage in an urban setting can create conflict with a city’s demands to develop. This paper first reviews the understanding of value within the heritage discourse and discusses extrinsic and intrinsic definitions. Then, using Vienna as an example, a Qualitative Content Analysis of texts from the disciplines of conservation, the law, building standards and city planning was undertaken. These texts form the basis for the city’s heritage policy, but as they are not harmonized, potential areas of conflict can arise. The findings show that the most striking difference lies in the definition of value, which some texts either define as being intrinsic or extrinsic. This difference in definition in the fundamental marker of heritage and the lack of coordination between various agents involved was identified as the main source of tension in Vienna’s heritage policy making. A unified, extrinsic definition of value would aid the efficient management of built heritage within an urban setting and allow for suitable development and maintenance of a historic city center as a sustainable living space.

Introduction

As of now, the conservation of heritage is a generally accepted goal in many societies. Teaching history as a subject is a fixed staple in education, and remembrance of the past is seen as something that adds to our knowledge and understanding of the world. Heritage – as a tangible object of this history – is valuable to us and “value has always been the reason underlying heritage conservation” (Torre and Mason Citation2002, 3). This paper focuses on heritage in an urban context, which can be distinguished from detached heritage assets: Built heritage in a city center is in constant tension between conservation and use; it must not only function as heritage as a remnant of the past but also as contemporary urban space. Therefore, it is not only subject to heritage policy but must also satisfy urban planning needs as well as building standards. Urban built heritage therefore cannot be considered in isolation but needs to be considered also in the context of meeting modern requirements, such as accessibility and reliability. In contrast to detached, single heritage sites, such as Stonehenge, the interconnected built heritage within an urban context consequently requires different management:

[…] the city is a multi-layered object, therefore the planners are asked to use their knowledge of the interpretation of the urban complexity and their ability to see the overlapping with other disciplines. (Colavitti Citation2018, 36)

A city center fulfills certain functions for its residents and visitors and these change over time; heritage policy needs to account for this change. As with other historic city centers, in Vienna this area functions as a shared space of identification for many of Vienna’s residents (TU Wien, Fachbereich Örtliche Raumplanung Citation2016). In order to preserve this function, built heritage is considered in urban planning and reflected in national and municipal legal texts.

Conservation charters and conventions which form the basis for heritage policy are a written reaction to political, societal and economic developments: the introduction to the UNESCO World Heritage Convention, for instance, begins with a declaration that the ongoing loss of cultural heritage is an impoverishment (Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage Citation1972). The fear of heritage loss is a great motivator for conservation work, and this impending loss forms the starting point for conventions and laws. For instance, the Venice Charter calls for cultural heritage to be “safeguarded” (ICOMOS Citation1964, 1).

As any conservation text has to be read and understood as a product of its time, its validity and topicality should be checked periodically, and adapted accordingly. While former ICOMOS Austria president Wilfried Lipp expressed his fear that cultural heritage is a “dramatically threatened and dwindling resource” two decades ago (Lipp Citation1996, 148), the heritage discourse has been widening its scope and now recognizes the creation of new heritage. The increasing number of heritage designations may be a response to the ongoing loss of heritage (Lipp Citation2008, 42) or a reaction to an increased awareness of diversity in policy making, which includes heritage.

Economic Assessment of Cultural Heritage

As a basic principle, it may be presumed that a society conserves buildings as long as they are beneficial to it, so value can be defined as the relationship of benefit and sacrifice (Thomson et al. Citation2003). As soon as sacrifice outweighs benefit, a building is likely to be demolished and the freed space will be used in a way which is more beneficial at that given point in time.

Over the past few decades, the field of cultural economics emerged as a new discipline, applying economic methods to measure the value of cultural goods. Cultural economists work under the assumption that the value of such goods is “not fully expressive in monetary terms” (Throsby Citation2006, 7). Throsby further argues for a distinction between economic value expressed in financial terms on the market and cultural value, which is “complex, multifaceted, unstable, and lacks an agreed unit of account” (Throsby Citation2010, 18). While this additional value can to a certain extent be measured by applying economic methods, some notions – such as source of identification – cannot be translated into economic terms and therefore remain elusive in regards to being measured or quantified.

To nevertheless include this additional value into policy making, Throsby suggests that experts define qualities which can be “expressed as, or converted into cardinal scores” (Throsby Citation2010, 22). This proves useful when managing cultural goods, especially when providing public funding, as it is usually necessary to provide a cost–benefit analysis to legitimize decisions (Towse Citation2005). And while there are critical voices that suggest measuring the value of a cultural good will eventually change its perceived value (Ellwood and Greenwood Citation2016), there is arguably a necessity to provide a framework for decision makers to act upon.

Even investing in a concrete plan how to manage built heritage itself can pay off and make a city competitive in the global market. While this requires a “tailored management as part of the government practice” (Guzmán, Roders, and Colenbrander Citation2017, 200), Bowitz and Ibenholt (Citation2009) found that the WH designation of a city center can have positive economic impacts on the region surrounding the site. A well-devised management plan therefore makes sense not only from a policy making standpoint, by facilitating decision making at different levels of governance, but also regarding the economic implications.

Furthermore, sites which are actively used and adapted are valued higher than those simply protected, as the everyday experience is significant (Wright and Eppink Citation2016). This, again, strongly indicates that the use and usefulness of heritage in the urban context should be considered when devising a management plan.

Intrinsic and Extrinsic Definitions of Value

There are two main theoretical approaches to establishing where the value of a building or any cultural good comes from: it can be defined as extrinsic, meaning that value is detached from the material and only created by the society that uses it, or as intrinsic, meaning that value is inherent to the material fabric and recognized by a society that uses it.

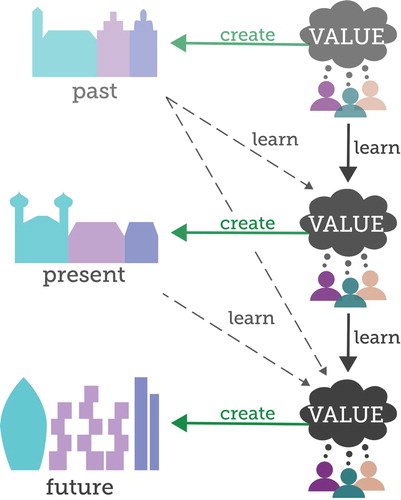

When using the extrinsic approach – and therefore assuming that a building’s value is “inherent to the vision of the observer” (Montella Citation2015, 15) – it is important for policy makers to include multiple points of view when analyzing both benefit and sacrifice. Not doing so would limit the validity of the assessment by excluding the experiences of a wide variety of groups of users. This challenge leads to an ongoing and lively debate on how to weigh different interests. On the one hand, different groups of users may have very different needs and requirements as regards the building stock, thus raising the question how to define a common ground between contrasting opinions. On the other hand, if value only exists through the reception of a group of people – who may or may not agree on the amount of value – and not in the material, it is something that has to be constantly negotiated. This negotiation can never be fully settled, and is therefore passed on from generation to generation, see .

Recently, the discourse has increasingly considered heritage as a process, thus acknowledging the multi-layered process of how value is created by a variety of users. This allows for a more critical and diverse assessment of the construction of value specifically and meaning generally.

The polarity of extrinsic or intrinsic definitions of value is a fundamental dichotomy in conservation and policy texts. While Alois Riegel wrote as early as 1903 that “we modern subjects” assign sense and significance (Riegl Citation1903, 7), texts provided by UNESCO and its advisory partner ICOMOS generally assume that cultural heritage possesses significance in and by itself. The Burra Charter, for instance, which applies the principles of the Venice Charter to an Australian context and was adopted by Australia ICOMOS in 1979, says that cultural significance is “embodied in the place itself, its fabric, setting, use, associations, meanings, records, related places and related objects” (Australia ICOMOS Citation2013).

There is an alleged objectivity and permanence to understanding value(s) as intrinsic, yet Labadi argues that an intrinsic definition of values prevents “the identification of a comprehensive statement of significance” (Labadi Citation2013, 148), which is especially relevant to urban heritage where multiple interested parties are constantly struggling to find agreement. A change of understanding of cultural value to be “multidimensional and multistakeholder” (Montella Citation2015, 36) makes the concept applicable to historic city centers.

When texts do not agree on either an intrinsic or extrinsic definition of value, this can lead to conflict. Ashworth (Citation2011) attributes these conflicts arising in the dealing with heritage in urban contexts to an incomplete paradigm shift, where three paradigms – preservation, conservation and heritage – coexist. The preservation paradigm, he argues, is echoed in fundamental ICOMOS texts such as the Venice Charter, and “focuses only on the intrinsic values of the structures with no essential concern for their functioning within the contemporary city” (Ashworth Citation2011, 12). This approach leads to fossilization of cities and halts their development. He therefore proposes as complete shift to the heritage paradigm in which value is constantly reassessed.

If heritage is understood as a cultural process, Jokilehto argues, its value can be understood as social association and is produced “[…] through cultural-societal processes, learning and maturing awareness” (Jokilehto Citation2006, 2). Therefore value can only be extrinsic and must be detached from the cultural object. This shift towards understanding heritage as a process is further discussed by, for instance, Smith (Citation2006); Jones (Citation2017); Apaydin (Citation2018); Lukas (Citation2018).

Case Study: Heritage Policy in Vienna

Organization of Heritage Policy

In the urban context of Vienna, heritage policy is multilayered and complex. Built heritage takes up a considerable amount of urban space and affects residents, visitors, building owners and various professionals from an array of disciplines. In addition, conserving historic structures is cost intensive and requires owners who can afford to do so. Austria and Vienna offer some small financial advantages to owning legally protected buildings, such as tax reductions or specific funding, yet developing and maintaining historic structures requires investors beyond private owners. In order to motivate stakeholders to invest their money in heritage, heritage is advertised as having more value than just its sales price or rental profit.

The complexity of urban heritage not only arises from the different groups involved, but also from the numerous legal texts and guidelines to be considered when it comes to conserving and modifying built heritage. In order to illustrate the complexity of the issue, a Qualitative Content Analysis of legal texts, guidelines and building standards affecting heritage policy of the historic city center of Vienna was undertaken. The analysis focuses primarily on the use of the terms value or significance and their understanding of being defined as intrinsic or extrinsic. The selected texts originate from different institutions with foundations in different disciplines and bear relevance on the fields of law, architecture, urban planning and civil engineering.

It is important to note that the legal system that governs heritage policy in Vienna consists of four agents: UNESCO, the European Union, the Republic of Austria and the City of Vienna. UNESCO and EU policy is realized in federal Austrian law, while the Austrian Heritage Protection Law (DMSG) itself also addresses heritage policy. The Vienna Building Code and additional guidelines define heritage policy further on municipal level. As neither federal law nor municipal law can trump the other, decisions regarding the World Heritage (WH) site should not contradict each other. In addition, European and Austrian Building Standards recognize built heritage and standardize their treatment for the building sector. While the rules and regulations set out therein should be applied in all building propositions involving built heritage, these texts are not legally binding.

Analysis of Legal Texts and Guidelines

The selected texts were sorted into groups depending on their spatial reach: Global, European Union, Austria and the City of Vienna. For each text a Qualitative Content Analysis was performed; the following information from each text is collected and summarized in :

| • | Marker of cultural heritage (e.g., value, significance) | ||||

| • | Intrinsic or extrinsic | ||||

| • | Goals (of conservation) | ||||

| • | Limitations | ||||

| • | Decision maker (party that assigns marker of cultural heritage). | ||||

Table 1. International texts on cultural heritage (CH).

Table 2. European texts on cultural heritage (CH).

Table 3. National and municipal texts on cultural heritage (CH).

Results

Global: UNESCO

All UNESCO texts considered in define value of a cultural asset as intrinsic (this corresponds with the assessment of Labadi (Citation2013, 12)). With regards to heritage in an urban context, these values are “[…] derived from the character and significance of the historic urban fabric and form” (Vienna Memorandum Citation2005, 3–4).

The “Historic City Centre of Vienna” was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage list in 2001; its core zone covers almost the entire area of the city center and expands partly into neighboring districts. Having signed the UNESCO World Heritage Convention in 1993, the state of Austria is responsible for the protection of its WH sites. The National Council of Austria decided that existing legislation was sufficient and no further laws were proposed (Perthold-Stoitzner Citation2013, 35). Other cities with urban heritage sites chose tighter legal measures, for instance in Hamburg, where the WH convention is included directly in heritage law, avoiding discussions on jurisdiction.

Even though the “Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention” demand the establishment of a management plan for all WH sites, no management plan for the Historic City Centre of Vienna site has yet been submitted. This lack of a management plan for the WH site has led to numerous conflicts of interests between agents proposing changes within the WH site.

One such conflict arose already shortly after the inscription onto the WH list, as a proposed high-rise development in the buffer zone threatened the WH site status. Due to pressure from ICOMOS, the original plans were amended and the WH site kept its status. A more recent dispute, which is still ongoing, again involved a high rise proposal, this time within the core zone of the WH site itself. Vienna’s refusal to change the plans after initial misgivings were voiced by ICOMOS led to the entire site being inscribed on the List of Heritage in Danger in 2017. While the original zoning of the area would not have allowed for the project to be realized, the lack of management plan allowed the municipal government to alter the zoning without checking with the other agents potentially involved.

Despite the controversies surrounding several high profile projects, some change within the city center is certainly possible along UNESCO guidelines, as stated explicitly in the Vienna Memorandum. Respecting the limitations of preserving authenticity and integrity, a small selection of new buildings, as well as significant alterations to lighting and paving are testament to one of the memorandum’s goals to “preserve the urban heritage while considering the modernization and development of society in a culturally and historic [sic!] sensitive manner, strengthening identity and social cohesion” (Vienna Memorandum Citation2005, 3). While the acknowledgement that change is possible and necessary is welcome, the guidelines are not clear on why some alterations constitute sanctioned interventions and others might lead to a loss of WH status. This leaves room for somewhat arbitrary distinctions being drawn, essentially adding to the tension already inherent in the relationship between international guidelines and national implementations thereof.

International: European Union

Two fundamental European texts that were introduced to protect cultural heritage are the Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society (Faro Convention), which Austria ratified in 2015, and the 1985 Convention for the Protection of the Architectural Heritage of Europe (Granada Convention), which Austria is planning to sign (BKA Citation2017, 10).

The most striking difference between the UNESCO texts and the EU texts is that the latter do not define value intrinsically (see ) and do not specify any limitations, such as authenticity or integrity (except for the criteria for the European Heritage Label). In stark contrast to the UNESCO texts, which mention the goal of protecting against value being lost if change happens to cultural heritage, the EU texts mention the goal of value being increased through research and understanding. Thus, while UNESCO recognizes only danger to the value when changes are implemented, the EU texts acknowledge the potential benefits of such changes and a resulting increase in value.

Taking a slightly more practical approach than UNESCO, the EU texts furthermore include the concept of accessibility. The importance of ensuring accessibility to a cultural heritage site is evidenced by this being a prerequisite for receiving the European Heritage Label.

Alongside the texts regarding heritage policy, building practice and the modification of built heritage are guided by several European Standards (EN), which apply to all cultural heritage buildings but are not limited to buildings that are legally designated so. These texts also include a definition of value, most explicitly in section 3.1 of EN 15898:2011 “Conservation of cultural property – Main general terms and definitions,” which states that cultural heritage is marked by aspects of importance (these can be artistic, symbolic, historical, social, economic scientific or technological) which are equal to value(s), the sum of these value(s) adds up to significance.

It should be noted that not all ENs which focus on cultural heritage agree on the extrinsic definition of significance: while in the actual definition of cultural heritage both EN 16096:2012 “Conservation of cultural property. Condition survey and report of built cultural heritage” and EN 16853:2017 “Conservation of cultural heritage. Conservation process. Decision making, planning and implementation” reference the original definition provided in EN 15898:2011, the introductions to both texts confusingly mention that significance is intrinsic to cultural heritage. The newest norms in the group of cultural heritage do not reference the 2011 definition and EN 16883:2017-08 “Conservation of cultural heritage. Guidelines for improving the energy performance of historic buildings” and PrEN 17135:2017 “Conservation of cultural heritage – General terms for describing the alteration of objects” only refer to cultural heritage in the introductions and suggest intrinsic markers of cultural heritage.

National: Austria

According to the Austrian Heritage Protection Law (DMSG), a building or an ensemble may be classified as a monument when its conservation is in the public interest due to its historic, artistic or other cultural significance as defined in §1 (1). As these properties are part of the object, the definition of value used is intrinsic. In §1 (10), significance is connected to documentation value as a basis for ascribing significance. The significance is assessed by the Austrian Federal Monuments Office (BDA) based on “scientific findings” (§1(5)) and may also include internationally accepted evaluation criteria, which are not further defined (Denkmalschutzgesetz Citation2013).

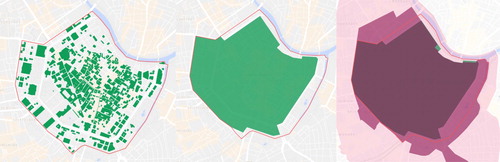

Currently, 48% of buildings in Vienna’s city center, covering approx. Fifty-eight percent of its area, are individually listed according to the Austrian Heritage Protection Law (DMSG). In addition, roughly the area within the Ringstraßen boulevard is protected as an ensemble, which in legal terms is equivalent to individual listing (see ). Ensemble listing is prioritized for UNESCO WH sites, and also covers the city centers of Graz and Salzburg.

Figure 2. (Left to right) individually listed buildings (green), ensemble (green), overlay WH site (purple) and ensemble. Map data ©2018 Google.

The DMSG was first introduced in 1923 and – despite comprehensive updating – still approaches heritage through a materialistic viewpoint, similar to UNESCO texts’ definition of value as an intrinsic characteristic. §1 (10) states that a prerequisite for a monument to be protected is a physical state which enables restoration, thus tying conservation directly to an object’s substance and physicality. Harrer (Citation2017) offers an alternative to this approach, arguing extensively that the exclusion of strongly deteriorated historical artifacts from conservation is no longer justifiable in the digital age, when digital reconstruction can let people experience heritage without heeding material authenticity, thus certainly meeting the criteria of public interest.

A materialist approach to heritage does not consider a building’s use and has serious implications for building owners, who are legally obliged to maintain a listed building. In practice this means that some choose to ignore constraints as demanded by the BDA and adapt their buildings to current building standards to avoid liability in case of accidents. As Austrian Building Standards do not distinguish between new and existing buildings, even historic buildings have to meet modern standards in case of renovation. This often creates conflict between the BDA’s demands for physical or material authenticity (Fersebner-Kokert and Kovar Citation2017) on the one hand, and the modern standards to be met on the other hand. A panel of building experts recently pointed out that there is an acute need to harmonize building standards and legal obligations in Austria, especially in the field of conservation (Kovar, Fersebner-Kokert, and Scheuder Citation2017). As this conflict of interests has been developing over some time, in 2014 BDA reacted with the publication of the “Standards of Built Heritage Care” guideline which are intended to ease communication between the BDA and building owners. These standards are intended to illustrate that conservation decisions are not “dogmatic” but relative (Euler-Rolle Citation2018, 106). As of now, the effects of these standards have not been publicized.

Municipal: Vienna

In contrast to the legal texts from UNESCO and DMSG, the Vienna Building Code, which operates at municipal level, does not apply to every part of the building. Its legal tool – the protected zone – merely protects a building’s impact on the cityscape. This impact depends only on the exterior of a building and does not extend to its interior. Any alteration to the “outer appearance, character or style” needs to be assessed by the municipal department MA19 (Bauordnung Für Wien. Citation2018). This presents a strong contrast to the materialist approach to heritage policy applied in the DMSG, as it neither defines value intrinsically nor is limited by material authenticity.

The concept of cityscape is also picked up by a planning guideline for building culture, where it is referred to as “a cultural value in itself that requires conservation” (Vassilakou Citation2014, 1). While the current City Development Plan (STEP2025) published by the municipality affirms that development in the city must conserve the “valuable built heritage” (MA 18 Citation2014, 35), a more detailed development plan for the area around the Ringstraßen boulevard acknowledges the necessity to embed historic substance into the “living city organism” (MA 21 Citation2014b, 6).Footnote2 Thus, the municipal government of Vienna clearly acknowledges the needs and requirements of a modern, growing city and its inhabitants at the same time as respecting its built heritage.

One means for addressing such necessary urban development are high-rise buildings, which are useful in creating housing space on small stretches of land. To ensure controlled development of such projects, the City of Vienna published a guideline on high-rise buildings which demands “elevated attention” when constructing buildings over a height of 35 m within protected zones and the UNESCO WH Site (MA 21 Citation2014a, 17). ICOMOS identified this guideline as a threat to the Outstanding Universal Value (OUV) of the WH site because it does not categorically exclude high rise construction within the WH site. ICOMOS’s concern was tested in the above-mentioned controversial Heumarkt project, where the zoning of the area designated for the proposed high-rise development was changed by the city government in 2017 so it was no longer included in the protected zone. This change allowed the building height to be increased up to 60 m, allowing the development to go forward. While the City Development Plan states that any changes within the WH site should be in accordance with UNESCO (MA 21 Citation2014b, 11), the city administration’s decision to move forward without ICOMOS approval resulted in the WH site being declared endangered (UNESCO Citation2017a).

Discussion

A Livable City

Heritage is a multi-layered concept with a variety of implications on the city and its residents: While heritage certainly plays a part in forming identity for a city’s residents, its economic impact can sometimes be deemed more relevant or noteworthy, and can – despite the issues described above – be easier to quantify. Vienna’s cultural heritage, for example, is a strong attractor for tourism and thus creates revenue, which amounts to approximately 5% of the gross regional product. The current development plan of the city, STEP 2025, credits tourism with “[…] helping to conserve the vast cultural heritage of Vienna […]” (MA 18 Citation2014, 75), but fails to mention how exactly this is accomplished, or how the costs of conserving heritage are offset by such revenues.

The constant growth of tourism – and the recent debate in the media about overtourism – in Vienna has raised an interesting question that should also be addressed by heritage policy: for whom should the city center be? Today, the population of Vienna’s city center is at its lowest since recording began in the sixteenth century; since 1984, the city’s development plans have been addressing the issue of decreasing numbers of residents in the center, the increasing use of space for offices, and more recently, the use of living space for short-term rentals and the commercialization of public space. So far, no solution for making the city center more attractive to live in has been found. In times of increasing population and a shortage of land to build on, increasing population density in the center, which is already perfectly equipped in terms of infrastructure, should be a priority in city planning.

City as a living space is often contrasted to city as heritage space, and the notion of finding a “balance” between seemingly opposite demands of these functions is reflected in the discourse:

Balance between old and new, between conservation policy and requirements for a lively city center, between sights and living space, as well as between peculiarity and normality need to be found to maintain the 1st district as a social and functional center of the city. (TU Wien, Fachbereich Örtliche Raumplanung Citation2016, 30)

Gründerzeit Nostalgia

The discourse on Vienna’s built heritage today is dominated by and often limited to the buildings constructed between 1858 and 1918, the so-called Gründerzeit. 60% of today’s city center buildings were constructed in these six decades. As a result of industrialization and subsequent urbanization, the city as a whole expanded rapidly in size, and the large apartment buildings from that era still dominate the city’s appearance.

Today, the Gründerzeit houses provide sought after living space, while attic conversions create upmarket densification (Kirchmayer, Popp, and Kolbitsch Citation2016). However, this current appreciation of the Gründerzeit buildings only began in the mid-1970s, even though a large proportion of the building stock had deteriorated strongly and living standards were poor. The introduction of policies protecting built heritage in Austria’s cities was driven by the population, manifested as protests against demolitions. Subsequent upgrading efforts by residents, in combination with funding for refurbishment, raised the market value and living standards significantly over the decades that followed. As more and more neighborhoods are being refurbished, housing costs rise, pushing out those who cannot afford it (Hammer and Wittrich Citation2016, 10).

The current city development plan includes an “Action Plan Gründerzeit” to combat this ongoing gentrification and social segregation (MA 18 Citation2014, 45). In order to preserve long-term low-cost rents in all buildings erected before 1945, a more recent change in the Vienna Building Code (§60(1d)) protects against these buildings’ unsolicited demolition. While this includes buildings from before the Gründerzeit, an explanatory text on the city’s website exclusively refers to Gründerzeit buildings as now being better protected (wien.at-Redaktion Citation2018). The potentially detrimental implications this policy change may have on the real estate market and quality of the building stock is addressed in (Bucher and Bucher Citation2019).

Conclusion

This paper discussed the current discourse on value in cultural heritage. It was argued that an intrinsic understanding of value cannot adequately reflect the challenges built heritage faces, especially in an urban context. The authors therefore propose an extrinsic definition, which is open to multiple perspectives and adaptable to ongoing changes.

An exemplary analysis of various texts from multiple disciplines which together comprise heritage policy in Vienna showed that these texts agree neither on value being defined as intrinsic nor as extrinsic to the artifact discussed, in this case buildings. This lack of harmonization leads to conflicts between agents that use and modify built heritage.

While there are powerful legal tools in place which ensure that the historic center will be maintained for future generations, the lack of a management plan which provides an overarching concept for the WH site, as well as limited cooperation between the agents involved, will continue to create tension. Currently, only the EU texts and building standards reflect the shift within the academic heritage discourse towards heritage being understood as a process, which is defined extrinsically, thus moving beyond its material and static form.

Heritage is part of the political discourse, which is why it should be inclusive, diverse and consider all citizens’ needs. An intrinsic definition of value does not allow for this to happen, as it can only conserve the status quo. The space of Vienna’s city center was mainly produced at the end of the nineteenth century and still defines people’s experience today. The city’s current heritage policy reinforces a demonstration of imperial power from past centuries and dramatically limits any development towards inclusivity and diversity, as it is focused on a very small part on the heritage spectrum.

UNESCO texts and Austrian Heritage Protection Law focus on the material, demanding authenticity and integrity, which is not sustainable for built heritage in an urban context. In order to create a livable city center that satisfies the needs of its residents, conservation laws and guidelines will have to adapt a uniform, extrinsic definition of value for cultural heritage. Only when policy recognizes that its value is defined by those who experience it, can cultural heritage be managed sustainably.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the TU Wien University Library for financial support through its Open Access Funding Program.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes on contributors

Barbara Bucher studied at the University of Vienna and has been a lecturer at TU Wien since 2016.

Andreas Kolbitsch studied and obtained his doctorate in civil engineering at TU Wien and subsequently spent 6 years in university teaching and research. Since 1999 he has been a full professor for building construction at TU Wien. His practical activities mainly cover the fields of classical structural engineering and structural renovation of old buildings.

Notes

1 For an extensive discussion on the Eurocentric development of conservation (see e.g., Jokilehto Citation1986).

2 While the municipal department MA19 is tasked with overseeing architecture and building design, both MA18 and MA21 deal with city development and land use. All three departments work closely together. Working more independently, MA37 oversees building projects in general and assesses whether they conform to the Vienna Building Code.

References

- Apaydin, Veysel. 2018. “The Entanglement of the Heritage Paradigm: Values, Meanings and Uses.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 24 (5): 491–507. doi:10.1080/13527258.2017.1390488.

- Ashworth, Gregory. 2011. “Preservation, Conservation and Heritage: Approaches to the Past in the Present Through the Built Environment.” Asian Anthropology 10 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1080/1683478X.2011.10552601.

- Australia ICOMOS. 2013. “The Burra Charter. The Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance.”

- Bauordnung Für Wien. 2018. “LGB l. Nr. 11/1930 IdF 37/2018. 28.06.2018.” Accessed July 23, 2018.

- BKA. 2017. “Baukulturelle Leitlinien Des Bundes Und Impulsprogramm.” Bundeskanzleramt, Abteilung II/4.

- Bowitz, Einar, and Karin Ibenholt. 2009. “Economic Impacts of Cultural Heritage – Research and Perspectives.” Journal of Cultural Heritage 10 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.culher.2008.09.002.

- Bucher, Barbara, and Christian Bucher. 2019. “Potential Futures: A Probability-Based Strategy for Maintaining Built Heritage in Vienna.” CSM8 Eighth Conference on Computational STOCHASTIC Mechanics, Paros.

- Bundesgesetz Betreffend Den Schutz von Denkmalen Wegen Ihrer Geschichtlichen, Künstlerischen Oder Sonstigen Kulturellen Bedeutung (Denkmalschutzgesetz – DMSG). 2013.

- Colavitti, Anna Maria. 2018. “Urban Heritage Management: Planning with History.” http://proxy.uqar.ca/login?url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-72338-9.

- Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage. 1972.

- Council of the European Union. 1985. "Convention for the Protection of the Architectural Heritage of Europe."

- Council of the European Union.2005. "Council of Europe Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society."

- Council of the European Union. 2011."Decision No 1194/2011/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 November 2011 Establishing a European Union Action for the European Heritage Label."

- Deutsches Institut für Normung E.V. 2011. Erhaltung Des Kulturellen Erbes – Allgemeine Begriffe; Deutsche Fassung EN 15898:2011. Berlin: Beuth.

- Deutsches Institut für Normung E.V. 2012. Erhaltung Des Kulturellen Erbes – Zustandserhebung Und Bericht Für Das Gebaute Kulturerbe; Deutsche Fassung EN 16096:2012. Berlin: Beuth.

- Deutsches Institut für Normung E.V. 2017a. Erhaltung Des kulturellen Erbes – Leitlinien für Die Verbesserung Der Energiebezogenen Leistung Historischer Gebäude; Deutsche Fassung EN 16883:2017.

- Deutsches Institut für Normung E.V. 2017b. Erhaltung Des Kulturellen Erbes – Erhaltungsprozess – Entscheidungsprozesse, Planung Und Umsetzung; Deutsche Fassung EN 16853:2017. Berlin: Beuth.

- Deutsches Institut für Normung E.V. 2017c. Erhaltung Des Kulturellen Erbes – Allgemeine Begriffe Zur Beschreibung von Veränderungen an Objekten; Deutsche Und Englische Fassung PrEN 17135:2017. Berlin: Beuth.

- Ellwood, Sheila, and Margaret Greenwood. 2016. “Accounting for Heritage Assets: Does Measuring Economic Value ‘Kill the Cat’?” Critical Perspectives on Accounting 38 (July): 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.cpa.2015.05.009.

- Euler-Rolle, Bernd. 2015. “Einführung.” In Standards Der Baudenkmalpflege: ABC, edited by Bernhard Hebert, 2., korr. Auflage, 6–13. Wien: Bundesdenkmalamt.

- Euler-Rolle, Bernd. 2018. “Management of Change – Systematik der Denkmalwerte.” In Die Veränderung von Denkmalen. Das Verfahren gemäß § 5 DMSG.Wolfgang Wieshaider, 97–106. Wien: Facultas.

- Fersebner-Kokert, Bettina, and Andreas Kovar. 2017. Bessere Rechtliche Rahmenbedingungen Für Baudenkmäler. Wien: Kovar & Partners.

- Guzmán, P. C., A. R. Pereira Roders, and B. J. F. Colenbrander. 2017. “Measuring Links Between Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Urban Development: An Overview of Global Monitoring Tools.” Cities 60 (February): 192–201. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2016.09.005.

- Hammer, Katharina, and Judith Wittrich. 2016. “Tschäntri Wås?” AK Stadt.

- Harrer, Alexandra. 2017. “The Legacy of Alois Riegl: Material Authenticity of the Monument in the Digital Age.” Built Heritage 1 (2): 29–40.

- ICOMOS. 1964. “International Charter for the Conservation of Monuments and Sites.”

- ICOMOS. 1994. “The Nara Document on Authenticity.”

- Jokilehto, Jukka. 1986. “A History of Architectural Conservation.” Recomposed PDF format 2005. https://www.iccrom.org/sites/default/files/ICCROM_05_HistoryofConservation00_en_0.pdf.

- Jokilehto, Jukka. 2006. “World Heritage: Defining the Outstanding Universal Value.” City & Time 2 (2): 1–10.

- Jones, Siân. 2017. “Wrestling with the Social Value of Heritage: Problems, Dilemmas and Opportunities.” Journal of Community Archaeology & Heritage 4 (1): 21–37. doi:10.1080/20518196.2016.1193996.

- Kirchmayer, Wolfgang, Roland Popp, Andreas Kolbitsch, and Verlag Österreich GmbH. 2016. “Dachgeschoßausbau in Wien.”

- Kovar, Andreas, Bettina Fersebner-Kokert, and Maroc Scheuder. 2017. Dialogforum Bau Österreich – Lösungsansätze Für Klare Und Einfache Bauregeln. Wien: Kovar & Partners.

- Labadi, Sophia. 2013. UNESCO, Cultural Heritage, and Outstanding Universal Value: Value-Based Analyses of the World Heritage and Intangible Cultural Heritage Conventions. Archaeology in Society Series. Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press.

- Lipp, Wilfried. 1996. “Rettung von Geschichte Für Die Reperaturgesellschaft Im 21. Jahrhundert.” ICOMOS – Hefte Des Deutschen Nationalkomitees, no. 21: 143–151.

- Lipp, Wilfried. 2008. Kultur Des Bewahrens: Schrägansichten Zur Denkmalpflege. Wien: Böhlau.

- Lukas, Scott A. 2018. “Heritage as Remaking: Locating Heritage in the Contemporary World.” In The Oxford Handbook of Public Heritage Theory and Practice, edited by Angela M. Labrador and Neil Asher Silberman, 1–13. New York: Oxford University Press.

- MA 18. 2014. “2025 Stadtentwicklungsplan Wien.” Magistrat der Stadt Wien, Magistratsabteilung 18 – Stadtentwicklung und Stadtplanung.

- MA 21. 2014a. “Fachkonzept Hochhäuser.” Magistrat der Stadt Wien, Magistratsabteilung 21 – Stadtteilplanung und Flächennutzung.

- MA 21. 2014b. “Masterplan Glacis.” Magistrat der Stadt Wien, Magistratsabteilung 21 – Stadtteilplanung und Flächennutzung.

- Montella, Massimo. 2015. “Cultural Value.” In Cultural Heritage and Value Creation Towards New Pathways, edited by Gaetano M Golinelli, 1–51. Cham: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-08527-2.

- Perthold-Stoitzner, Bettina. 2013. “UNESCO-Weltkulturerbe.” In Standards Für Ensemble-Unterschutzstellungen. Bundesministerium für Unterricht, Kunst und Kultur, Bundesdenkmalamt.

- Riegl, Alois. 1903. Der Moderne Denkmalkultus : Sein Wesen Und Seine Entstehung. Wien: Braumüller.

- Smith, Laurajane. 2006. Uses of Heritage. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis.

- Thomson, Derek S., Simon A. Austin, Hannah Devine-Wright, and Grant R. Mills. 2003. “Managing Value and Quality in Design.” Building Research & Information 31 (5): 334–345. doi:10.1080/0961321032000087981.

- Throsby, David. 2006. “Introduction and Overview.” In Handbook of the Economics of Art and Culture, edited by Victor Ginsburgh and David Throsby, 1st ed., 3–22. Handbooks in Economics 25. Amsterdam: Elsevier North-Holland.

- Throsby, David. 2010. The Economics of Cultural Policy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Torre, Marta de la, and Randall Mason. 2002. “Introduction.” In Assessing the Values of Cultural Heritage, edited by Marta de la Torre, 3–4. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute.

- Towse, Ruth. 2005. “Introduction.” In A Handbook of Cultural Economics, edited by Ruth Towse, 1–8. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- TU Wien, Fachbereich Örtliche Raumplanung. 2016. “Wien: Polyzentral. Forschungsstudie Zur Zentrenentwicklung Wiens.” Werkstattberichte Der Stadtentwicklung Wien 158. Stadt Wien, Magistratsabteilung 18 – Stadtentwicklung und Stadtplanung.

- UNESCO. 2005. “Vienna Memorandum on ‘World Heritage and Contemporary Architecture – Managing the Historic Urban Landscape’ and Decision 29 COM 5D.”

- UNESCO. 2010. “Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape.”

- UNESCO. 2017a. “Decision : 41 COM 8C.1. Update of the List of World Heritage in Danger (Inscribed Properties).”

- UNESCO. 2019. “List of World Heritage in Danger.” April 15. https://whc.unesco.org/en/danger/.

- UNESCO. 2017b. "Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention."

- Vassilakou, Maria. 2014. “Vorwort.” In Baukultur Wien – Ein Programm Für Die Stadt, 1. Magistrat der Stadt Wien, MA19 – Architektur und Stadtgestaltung.

- wien.at-Redaktion. 2018. “Verbesserungen Im Wiener Baurecht.” September 8. https://www.wien.gv.at/bauen-wohnen/bauordnungsnovelle.html.

- Wright, William C.C., and Florian V. Eppink. 2016. “Drivers of Heritage Value: A Meta-Analysis of Monetary Valuation Studies of Cultural Heritage.” Ecological Economics 130 (October): 277–284. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2016.08.001.