ABSTRACT

In exploring children’s play in a mobile preschool this article aims, with an in-depth review of play situations, to show how children within collective fantasy play engage with spaces and experiences of the preschool bus. An ethnographic study with video observations was carried out in a Swedish mobile preschool, and a spatial dimension was added to a theoretical perspective on children’s interpretive reproduction in order to focus on how children create places in fantasy play. The analyses show how children in place-making processes innovatively connect and transform outdoor and indoor spaces into resources in play, and create diverse mutable play resources such as drills, a steering wheel and imaginary seatbelts. The results suggest that within collective fantasy play the children negotiate the meaning of issues about vehicles, such as the usage of seatbelts and vehicle breakdowns, and create imaginative extensive play-places – their own novel formations of place within the mobile preschool.

Introduction

Children playing within a mobile preschool in Sweden – a preschool revolved around the usage of a bus – engage with spaces that can be mutable and contrasting. Playing indoors can refer to play that occurs inside the bus, which is primarily intended for transporting children and staff to different areas and for daily preschool routines. By contrast, playing outdoors can refer to play within various green areas, which include a variety of natural objects (e.g. stones and sticks).Footnote1

The children in this article are among the youngest in a preschool group participating in a mobile preschool practice with organizational space to play both indoors and outdoors. To understand how children in play encounter, make meaning of and collectively participate in creating places within the mobile preschool, this article explores how children engage with spaces and experiences of the preschool bus in collective fantasy play.

The theoretical perspective on interpretive reproduction, as formulated by Corsaro, assists in understanding children’s participation in society as not merely internalization of culture and society, but as creatively and collectively – within their peer cultures – contributes to cultural production and change (e.g. Corsaro, Citation2011, Citation2012, Citation2018; Corsaro & Molinari, Citation2008). The concept interpretive reproduction has contributed to earlier research on peer cultures and play analysing how children collectively participate in different play routines by simultaneously using different communicative skills in collective actions (e.g. Evaldsson & Corsaro, Citation1998; Manso, Ferreira, & Vaz, Citation2017). In this article, a spatial dimension is added to Corsaro’s theoretical perspective on children’s interpretive reproduction (e.g. Corsaro, Citation2018). I add a perspective on space and place (e.g. Massey, Citation2005) by analysing how children in peer cultures within the studied mobile preschool participate in place-making fantasy play. How children, in fantasy play, collectively engage with spaces and experiences of the mobile preschool and how their places for play emerge in interpretive processes is thus brought to the foreground by this choice of theoretical points of departure. Thereby, I focus on how the children create and recreate places, as well as on their meaning-making of everyday experiences, such as when they negotiate safety routines. This article aims in this way to contribute to the field of young children’s play within early childhood research by increasing the understanding of how preschool children, in collective fantasy play, engage with different spaces and practices.

Theoretical points of departure

With an emphasis on children’s agency (e.g. James, Citation2011) fantasy play can be seen as an everyday activity, collectively produced by children, that contributes to their, so-called, peer cultures (e.g. Corsaro & Johannesen, Citation2007). In this article, I understand peer culture ‘as a stable set of activities or routines, artifacts, values, and concerns that children produce and share in interaction with peers’ (Corsaro, Citation2015, p. 19). However, this also means that children, as participants in the interwoven cultures of children and adults, appropriate and transform parts of the adult world while playing (Corsaro, Citation2012); the children’s agency can be seen in this process.

Corsaro’s concept of interpretive reproduction emphasizes that children don’t simply internalize cultures in society; rather they participate in contributing to change and producing culture. Creative and innovative aspects of children’s participation in society are captured by this concept: in striving to make sense of the adult world, children use and interpret information from adult culture. Through this process, the children participate in and create their own peer cultures. The concept of interpretive reproduction also shows how, through their participation in society, children can be seen as constrained by social structures (e.g. Corsaro, Citation2018).

Children’s participation in cultural routines is a key element of interpretive reproduction (Corsaro, Citation2018). Fantasy play can be considered as a basic routine in preschool children’s peer cultures. Within the framework of fantasy play, children can produce, display and interpret sociocultural knowledge (Corsaro, Citation2018; Corsaro & Johannesen, Citation2007). This routine is often very complex, implicit and produced by the children in an emergent manner – i.e. improvised and constituted within the ‘frame’ of the interaction itself (Corsaro & Johannesen, Citation2007).

In this article, in order to focus on how children create places within fantasy play in their peer cultures, I add Massey’s relational view on spatiality to Corsaro’s theoretical perspective on interpretive reproduction. In Massey’s understanding, space is produced in social relations and can be articulated as being ‘always under construction’ (Massey, Citation2005, p. 9), i.e. constantly in a process of being created. Created through interactions, space is viewed as a sphere in which different coexisting stories meet and affect each other (Massey, Citation1999). Thus, space is understood as both mutable and a matter of multiplicity. Within this perspective, place can be seen as a formation – an event in process within the broader concept of space (Massey, Citation2005).

In Massey’s view, spaces and places emerge through practices. We continually participate in the process of this production (Massey, Citation2005). When we arrive in a place, we connect to a collection of stories: the ‘interwoven stories, of which that place is made’ (p. 119); this causes a change (followed by more changes).

Massey’s philosophical view embrace reimagining of space and place but also more, such as material changes (inter alia associated with, so-called, nature or countryside, e.g. erosion and movements of icecaps and mountains) (Massey, Citation2005). In this article, by placing human agency in the foreground of my interpretation of Masseýs view on the (never finished) production of space and place, I view children’s places within the mobile preschool as formations in process. In emphasizing the children’s agency, the places produced are seen as the children’s formations – their events of place. The children are seen as continually constructing places through their practices. Fantasy play is accordingly considered as a practice through which places emerge (cf. Massey, Citation2005), and as a routine within the children’s peer culture in which the children produce and interpret cultures, including that of the mobile preschool (cf. e.g. Corsaro & Johannesen, Citation2007).

The mobile preschool in a Swedish context

Since 2007, mobile preschools (Hellman & Sunnebo, Citation2009) have gradually been established as an alternative form of preschool in several municipalities in Sweden inter alia because of pedagogical reasons (see Gustafson, van der Burgt & Joelsson, Citation2017).Footnote2 This phenomenon also occurs in two other Nordic countries, Denmark and Norway (Gustafson & van der Burgt, Citation2015).Footnote3 The Nordic way of doing mobile preschool means using a bus to bring children to different places. This makes it possible to offer the children experiences through activities and learning environments outside the ordinary preschool (see also Ekman Ladru & Gustafson, Citation2018).

Play is seen as essential in Swedish preschools. Although new formulations of goals have turned much focus towards learning, the importance of play is still emphasized in the preschool curriculum. As an example, it is e.g. emphasized that children learn through play (see Sverige. Skolverket, Citation2018). In Swedish preschools, it is traditionally common to have daily time for ‘free play’, during which children can choose what to play and, to some extent, where and with whom. Free play occurs both indoors and outdoors, regardless of weather (Lillvist & Sandberg, Citation2015). There is a traditional view that natural outdoor play contexts are important for children’s play and learning (Änggård, Citation2010; Gustafson et al., Citation2017; Lillvist & Sandberg, Citation2015). In addition to organized play, the studied mobile preschool offered plenty of opportunities for ‘free play’ outdoors (mostly in green areas), as well as indoors. However, free play inside the bus cannot be seen as a given fact. A national mapping has shown that although Swedish mobile preschools organize their activities differently, there is a general emphasis on outdoor activities and play (Gustafson et al., Citation2017).Footnote4

Children’s agency in play

The theoretical points of departure in this article emphasize children’s agency in cultures (e.g. James, Citation2011; Mayall, Citation2002). This view, a characteristic of much research in childhood studies carried out since 1970s, embraces an understanding of children as agents (Qvortrup, Corsaro, & Honig, Citation2011) and appears inter alia in earlier research showing that children, in play, construct and transform their contexts to make sense of the world (e.g. Corsaro & Johannesen, Citation2007; Evaldsson, Citation2011; Schwartzman, Citation1978). Studying content in play can reveal issues that children consider to be important. In constructing shared meaning – in order ‘to understand their situation’ (Löfdahl, Citation2002, p. 209) – children use cultural themes such as power relations and existential questions in play. However, these themes should be seen as culturally and socially changeable. Löfdahl depicts children as social actors who can construct new meaning-making in play by combining diverse contents.

In their play, children may interpret components of cultures very broadly and may make combinations in a way that leads to a result with very little resemblance to the source. For example, Evaldsson and Corsaro (Citation1998) demonstrate that children’s play can be spontaneous and very improvizational. Similarly, recent research by Manso et al. (Citation2017) on children’s body language in relation to play describes an unpredictable process:

wherein children think and imagine situations from the world around them, while exploring, composing and performing a blend of characters, roles and events that has never before been enacted. Exploration, composition and performance happen simultaneously, and all elements merge in public. (classroom) (p. 142)

Manso et al. (Citation2017) suggest that the processes that are collaboratively used by children when freely playing together can be viewed as aligning with processes from dance choreography, for example in terms of the aspect of improvization. Building on Corsaro’s work, Sawyer (Citation1997) emphasizes children’s improvizational creativity. Sawyer stresses that children collectively improvise and produce narratives in pretend play,Footnote5 and that social structures are used by children to create novel improvised interactions (Ibid). That children use different verbal routines (e.g. voice quality) to signal that they are making up play scenarios is shown in research on children’s verbal communication in play (Björk-Willén, Citation2012; Corsaro & Johannesen, Citation2007; Lodge, Citation1979).

The potential for different types of play depends on adults prevalent play practices – i.e. how adults (e.g. playworkers) facilitate certain kinds of play depends on how they think about play (Kane, Citation2015). Furthermore, more possibilities for play may appear as children manage and redesign structural arrangements. For example, children’s agency can be seen in their own discovery that a sofa, which is intended for sitting, can also be jumped on (Eriksson Bergström, Citation2013). Similarly, two studies on Scandinavian mobile preschools show that children create space for play as they walk in line, which could be considered as a bodily constraint (Ekman Ladru & Gustafson, Citation2018; Gustafson & van der Burgt, Citation2015).

Space and place created in play, and play as situated

How we understand childhood and children, for example if there is a common notion that children should attend preschool, affects in general how we think about and study places and spaces for children as well as childreńs places (see Holloway & Valentine, Citation2000). Earlier research on young children and space predominantly focuses on physical (material) space (see Vuorisalo, Rutanen, & Raittila, Citation2015). The present article, however, includes both social and material aspects in a relational view of space and place. Considering space and place as being created in play, and play as being situated, I will here address earlier research that is relevant for the present study and that resonates with a relational view on spatiality, although the emphasis on physical and social space may vary.

Earlier research has revealed a reciprocal relationship between places and children’s play. For example, places can be viewed as children’s social constructions, while children’s activities such as play can be viewed as socially situated – i.e. as taking ‘place in places that invite participation in various activities’ (e.g. Gustafson, Citation2009, p. 13).

Rasmussen (Citation2004) discusses children’s places, which are places to which children attribute special meaning, and places for children, which are places created by adults for children. What children are supposed to do in a place for children and how children interpret this, are not always aligned. Rasmussen stresses that within places for children, the children themselves create places. The question of whether tolerance towards children’s places decreases as places for children are designed arises in this context.

How places for play are constructed by both children and adults in the preschool have been illustrated in a study that views adults’ dramatizing and children’s fantasy playing as loading places with symbolic meanings (Änggård, Citation2012). Änggård argues that these practices contribute to the process of giving identity to places. Furthermore, the physical environment (both its character and human usage of it) is highlighted as important for how play and place are created (Ibid). Änggård (Citation2009), along with other researchers (e.g. Eriksson Bergström, Citation2013; Morrissey, Scott, & Rahimia, Citation2017), argues that children use tools that have been designed in a non-static (neutral) fashion in various ways in their play. Thus, objects that are not clearly defined (i.e. open-ended materials) provide different possibilities for children to interpret, imagine and transform. Eriksson Bergström (Citation2013) demonstrates that children’s collective play in which they negotiate action often occurs in rooms with neutral objects. This finding aligns with research on how children in a preschool with an outdoor focus use resources of nature (e.g. natural objects such as sticks) in their imaginative play (Änggård, Citation2009). When playing in a natural environment using materials from nature, children spend a great deal of time negotiating meaning-making, which includes giving objects meaning by identifying them as various artefacts. In line with the work of Vygotsky (Citation2004), Änggård (Citation2009) emphasizes that children’s imagination builds upon (so-called) reality. In order to be able to use an object as a substitute for something else in their imagination, children need experience to build upon. Vygotsky (Citation2004) formulates this idea as ‘The richer a person’s experience, the richer is the material his imagination has access to’ (p. 15). Änggård (Citation2009) suggests that play themes build on children’s own experiences, toys and media (e.g. fairy tales) but also that the natural material invites children to play themes that integrate the natural environment. The children in Änggård’s study create particular places with recurring play themes, and bring cultural experiences to their play through an interpretive process.

In a study of children’s embodied meaning-making in a museum, Hacket (Citation2015) stresses that children’s use of space may influence how that space is understood by adults. Hacket suggests that when the meaning of communication doesn’t only include written and spoken words but also, for example, gestures and movement (e.g. running), the concept of space should be considered.

In a Swedish context, preschool can be regarded as a common form of space for many children, as well as play is seen as essential (mobile preschools is however an unusual form of spatiality). In this article, I add a spatial dimension to the theoretical perspective on interpretive reproduction in order to analyse children’s place- and meaning-making fantasy play within a mobile preschool. Thus, I analyse how the children’s places emerge through their fantasy play practices, which include communication consisting of movements, spoken words and gestures, as well as their engagement with space and experiences of the preschool bus.

Methods

After gaining the acceptance of children, parents and preschool staff in a mobile preschool in the south of Sweden I carried out an ethnographic study (e.g. James, Citation2001) from October 2016 to June 2017. During participant observations, I made video recordings with a hand-held camera, took photographs and made field notes. I also participated in activities such as visiting teacher planning sessions. This article is primarily based on video observations of children’s play. As in all ethnographic research, I (by my very presence alone) have been a part of the field, even if the children really seemed to accept my filming and me. Occasionally I simply seemed to be an appreciated audience.

While reviewing the video recordings I made notes. Among the children in the studied mobile preschool, situations which could represent examples of recurrent spontaneous fantasy play (vehicle play) were chosen and from these video observations stills were captured.Footnote6 Since the video observations were made during late autumn and early spring (during which it is often cold and rainy) this affected the daily time the children were playing outdoors. More indoor play could be expected in this mobile preschool during the cold seasons compared to the warm seasons. A choice were made in this article to focus on the youngest childreńs fantasy play (children in the ages of 3–4 years), but the chosen fantasy play occurred also among older children.

The ethnographic study is part of a project (Gustafson & van der Burgt, Citation2016) that has been approved by the regional ethical board, and principles for research ethics (Vetenskapsrådet, Citation2017) have been followed. Consents from all participants were secured and their names have been changed. Recognizable faces in figures presented in this article have been replaced with sketches.

A study in a Swedish mobile preschool setting

I carried out fieldwork with video observations (39 h) in the mobile preschool for two weeks in late autumn and two weeks in early spring. In the south of Sweden, dominant outerwear during these seasons is insulated overalls or waterproofs, boots, gloves and knitted caps.

The 3–4-year-old children in this article are part of a preschool group of 17 children, aged 3–6 years. The staff consist of one qualified preschool teacher (who also is the driver), and two nursery nurses. The group travels every day in a specially designed bus to chosen destinations within the city and its surroundings. During travel, the children sit in child-safety seats and their seatbelts are controlled by the staff before departure. The destinations are typically about half an hour away from the city-based preschool building, which is where the children arrive in the morning and leave from in the afternoon. The mobile part of the preschool day, when activities are carried out using the bus in different ways, is between 9 AM and 3 PM. Popular destinations include different green areas outside the city.

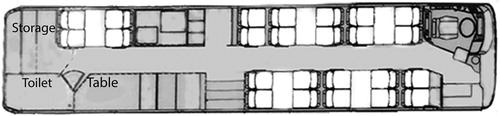

The preschool organization enabled multiple opportunities for the children’s ‘free play’ both indoors and outdoors. Spontaneous fantasy play was encouraged in different ways, including time-spatiality and the staff’s approach to fantasy (which e.g. pervaded planned activities). During free play, children had opportunities to create fantasy play on their own within peer groups, or to choose other play activities (e.g. taking part in games or building activities). Play objects, which were readily available for indoor play (inside the bus), included a modest number of toys, games and other typical preschool materials. In the bus (), many of the seats were placed in groups of four together with a table, and there was a small folding deck for play by the back stairs.

The staff’s approach to the children’s utilization of spaces related to the mobile preschool was visible in how they worked to free up as much of the physical space inside the bus as possible for play, and in how the bus was carefully parked to connect with the green areas visited. This approach created opportunities for the children to use a great deal of the physical space inside the bus in their play, in addition to abundant physical spaces outside of the bus. However, space for free play was organized so that all the children were either inside or outside of the bus at the same time.

Results

At the time of this study, a recurrent spontaneous fantasy play in the mobile preschool during ‘free play’ time was about vehicles. The combinations of children playing together varied, and the children changed the content from one time to another, as well as during the same play. In this way, the children collectively constructed and reconstructed play about an imagined vehicle.

In cold and humid weather, the children could remain inside the bus until lunch, which was a common case during the fieldwork. The daily outdoor play generally meant play situated in green areas that were frequently visited. Here, by analysing examples of the fantasy vehicle play that took place both inside and outside of the bus, I will explore how the children engaged with spaces and experiences within the mobile preschool. The chosen examples demonstrate how, in their place-making play, the children engage with the materiality of the bus and with experiences that are characteristic of the mobile preschool, such as the need to wear seatbelts and that vehicles can break down and be repaired.

Example 1. Fantasy vehicle play indoors– children transforming and connecting spaces and experiences of the bus in an interpreting process

Setting

During indoor play, the children had free access to objects within a locker they could open by themselves. Other play objects were also available, which the staff helped the children to access. In addition to various play activities, such as games and building projects, initiated by both children and adults (adults were present and engaged in many of the indoor activities), there were opportunities for the children’s own fantasy play.

The children could move about and utilize the entire interior of the bus, except for the driver’s seat and a compact storage area. They could also move certain things to places in the bus where they were needed in the play.

Transforming spaces of a bus into resources in a vehicle-repair play

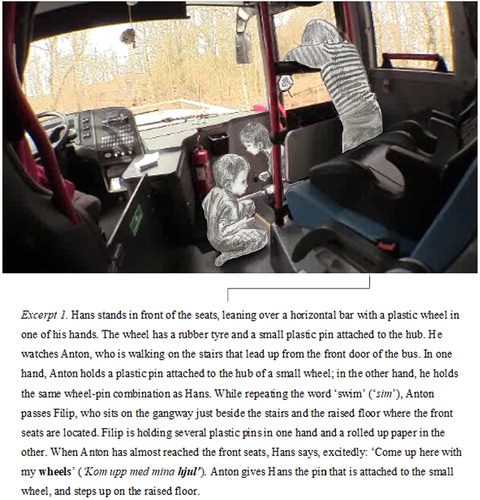

The bus malfunctioned for a while and was sent to the garage for repairs. This malfunction, which involved the bus heating system, was very noticeable to the children. In this example, it is morning, shortly after the bus has been repaired. The children play freely for a while inside the bus. The staff are engaged in various games with some of the children. Anton, Filip and Hans are playing on and around the two seats at the very front of the bus (). They have brought over wheels and plastic pins from a building project elsewhere in the bus. I observe their play, in which they use the interior of the bus around the two front seats with their body movements and positions. A play-place – i.e. the children’s own place for play – is successively created and recreated within the children’s collective fantasy play, as emerges in the following analysis.

A horizontal bar, stairs, gangway and raised floor constitute the surface being utilized by the children (see ). As Anton repeats the word ‘swim’ while moving on the gangway, an imaginative place is momentarily created (cf. Massey, Citation2005), which seems to be something you can swim in. Hans doesn’t leave the raised floor where the front seats are but follows Anton with his gaze. When Anton approaches, Hans coaches him to ‘come up here’ with the ‘wheels’. Hans says this excitedly, stressing the last word (naming the combined object) and Anton responds by handing over the object. The character of the space is used by the children in creating their play-place. The imaginary dimension of the space beneath the raised floor, as a swimmable place, is a far stretch from the original function of the stairs and gangway.

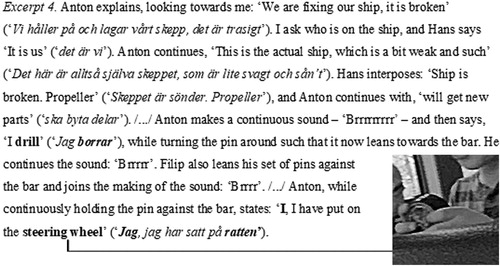

When Anton steps up on the raised floor, his action implies that he joins the next part of the emerging play-place, a formation in process (cf. Massey, Citation2005). Gradually, the children collectively put the modest objects in their hands into use (see ).

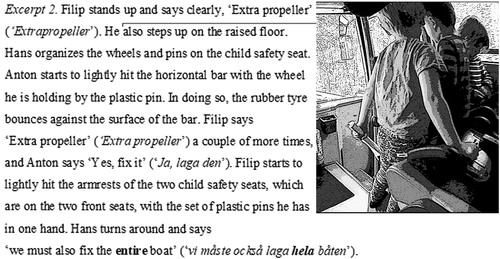

When Filip steps up on the raised floor, the three children come very close together in front of the seats. Without intruding on the space for the other children’s bodily movements, Hans uses the child-safety seat as a play workplace. An artefact – called an ‘extra propeller’ by Filip – emerges temporarily, while an imaginative place is externalized in the children’s acting. Successively, with the confirmative utterance from Anton, ‘Yes, fix it’, and with Anton’s and Filip’s use of the objects in their hands to lightly hit parts of the furnishing, the play-place becomes clearer. Hans’s statement ‘fix the entire boat’ clarifies the place further; it is a boat, and the stressed word ‘entire’ indicates that the vehicle is large.

One function of the objects held by the children is to be used to hit something else. The child-safety seats and horizontal bar in the bus are used as targets. The objects and the furnishing of the bus are in this way transformed into resources within the play. In playing together, social interaction is crucial for the shaping of meaning. Each child’s movements are carefully explicit, attuned with the other children’s emplacement within the modest physical space. The play theme is improvised within the frame of the play itself, without any instructive talk outside the collective fantasy play (see Corsaro & Johannesen, Citation2007). Both words and bodies’ emplacement are part of the improvization and creation of the place.

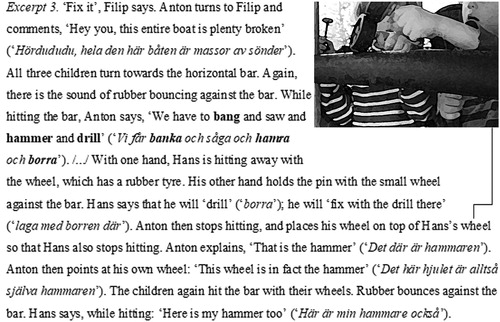

In the next sequence (see ), the play-place-making process is further articulated through the actions, negotiations and explanations shared by the children; their transformation of the objects continues, and the objects are turned into a new use. This starts with Filip, who takes a wheel that Hans has left on the child-safety seat. Filip uses the wheel to hit the armrests.

The children continue to collectively interpret and transform the furnishing of the bus, as well as the objects available, into resources in their play. They negotiate and create meaning of the wheels, pins and bar with explicit movements and words. New functions arise through the transformation process – ‘to bang and saw and hammer and drill’ – and the imaginative artefacts are thus reshaped. The play is improvizational and open for negotiation (cf. Evaldsson & Corsaro, Citation1998; Manso et al., Citation2017; Sawyer, Citation1997). In the negotiation, within the play (see Corsaro & Johannesen, Citation2007) and about what meaning should be interpreted, both verbal words and bodily movements (including showing objects) are of importance. Anton’s placement of his wheel on top of Hans’s wheel while stating ‘This is, in fact, the hammer’ is a proposal regarding what kind of resource they have in hand at the moment. Hans accepts the proposal with his answer, which includes both movement and a verbal comment.

That the negotiation is public (see Manso et al., Citation2017) becomes clear when the children include the observer while explaining their play (see ).

These explanations are like translations directed to me, the observer. The children talk outside of their frame of play (cf. Corsaro & Johannesen, Citation2007) to me – the adult. This articulation of their practice so far – i.e. an event in process wherein the children engage with the space of the bus – is for me, since the children don’t really need it for themselves in their collective fantasy play. The imaginative place for play – the children’s own play-place – emerges as a ship, and the momentarily transformed function of the artefact is clarified: what before was used as the handle for a hammer, is now reconstructed and presented with the sound of a drill, followed by a verbal proposal. Thus, the children turn the former artefact into a new resource in the play; they now have a drill. Filip is the one who accepts the proposal this time. He shows his acceptance by leaning his pins against the bar while making the sound of a drill. In the next turn, however, Anton puts an end to this part of the play with: ‘I, I have put on the steering wheel’. According to this non-negotiable proposal, the newly created resource is a steering wheel.

To sum up, in this example, the children handle how to fix a broken vehicle with different tools, in what can be understood as an interpretive reproduction (see Corsaro, Citation2018). This turn of the fantasy vehicle play emerges after a bus malfunction has affected the mobile preschool for a while. The children use the furnishing of the bus and imagined tools to create the mutable play-place. In a collective improvised process, the children turn the materiality of the bus and their experiences with it into resources in their play. The children’s sociocultural knowledge (see Corsaro & Johannesen, Citation2007) is essential in creating novel, improvised interactions (cf. Sawyer, Citation1997), and the play-place is created through the process of social relations (cf. Massey, Citation1999, Citation2005). Through the children’s interactions, the space of the bus is transformed, and their play-place emerges in the process.

Playing bus in the bus – children connect outdoors and indoors

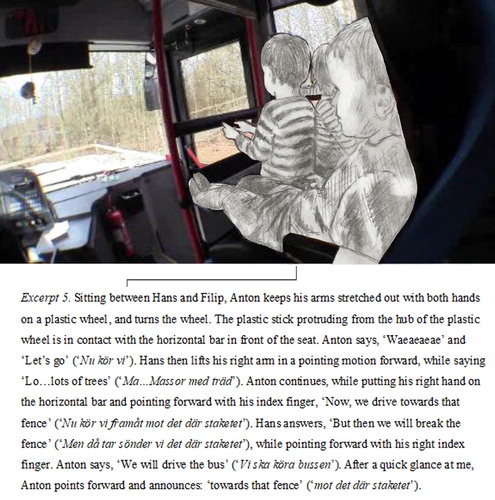

The play continues with a vehicle theme, albeit now with a new direction (see ).

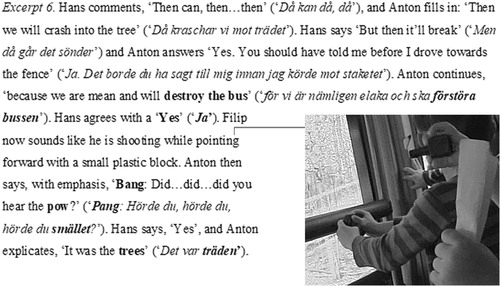

Anton, who sits between Filip and Hans, explicitly handles the combined objects in his hands: the plastic wheel, with the plastic stick attached, is used as if it is a steering wheel. In connecting the objects to the horizontal bar and making turning movements he creates a new resource. The play is situated in an imagined driver’s seat; with his movements, Anton has established that he is the driver. With their bodies emplaced in the seats at the very front of the bus, like a real driver’s seat, the children have a clear view through the windscreen. Hans comments about the trees outside the windscreen; in this way, while turning the fantasy play towards a situation with fictive danger, he transforms the play-place. Now the place also includes materiality outside the bus: outdoors and indoors are thus connected. Anton widens the construction further by using the fence, also seen outside, when stating that they will drive towards it. Hans states the consequence: they will ‘break the fence’. Anton holds on to the construct: they ‘will drive the bus’ and it will be ‘towards that fence’. However, when stating this, Anton makes a micro pause. Before pointing forward, he glances at me who is standing close by. The public nature of the negotiation (cf. Manso et al., Citation2017) once again becomes clear. The transformation process continues (see ).

Collectively, through a weaving process, the children connect outdoors with indoors. They ‘will crash into the tree’ and the consequence is, as Hans proposes, ‘it’ll break’. What seen outdoors, through the windscreen, is after this established as turned into a resource and as a part of the play-place: Hans ‘should have told’ Anton the consequence before Anton ‘drove towards the fence’. Here, Anton actually steps out of the frame of the play in his talk. (The reason can be that he is pointing out a temporal problem in the improvised fantasy play [cf. Corsaro & Johannesen, Citation2007]). Anton continues by saying that they are ‘mean and will destroy the bus’. Hans agrees. Filip now sounds like he was shooting while pointing forward. This movement is important for the collective construction of the play as it leads to Anton’s next statement: with a ‘bang’ and a ‘pow’ they broke the trees.

In their meaning-making, the children are dealing with things that break and why they break. Although the space in this episode can be seen as constrained, the children transform it into resources. What they view outside the windscreen, the trees and the fence, are included as important parts in their construction of play and place. The children make their play-place pass beyond the boundaries of the windscreen and the organization of the preschool. Their play-place is given a wide range since the children connect indoors and outdoors. This contrasts with that the children during this play episode are bodily constrained to be indoors – inside the bus. They can’t in this moment physically (with their bodies) go outside and play out smashing into the trees or the fence.

Example 2: children creating play-places and transforming the seatbelt into a resource in fantasy vehicle play outdoors

The importance of seatbelt is emphasized in this mobile preschool. The children learn to put seatbelts on by themselves, but the belts are also checked before the bus starts. During the fieldwork, I observed that the moment the bus engine stopped, the children opened the seatbelts by themselves. None of the adults needed to say anything. Here, this rule could be interpreted as: ‘as long as the engine is on, the seatbelts also need to be on’.

In Example 2, I will analyse fantasy vehicle play outside the bus. The chosen excerpts show how the children make sense of wearing a seatbelt in their place-making play. In the first part, the children create an ambulance-train; in the second part, they create an airplane.

To wear or not to wear seatbelts in an ‘ambulance-train’ – interpretive reproduction with the negotiation of safety rules

During the fieldwork, the seatbelt became visible in the children’s fantasy vehicle play.

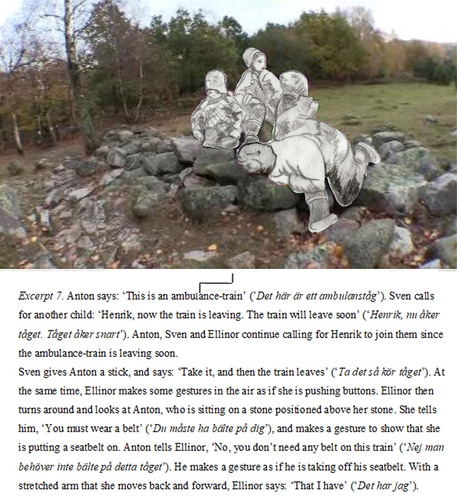

In this example the children are, in the process of creating a play-place and within interpretive reproduction, negotiating how a safety rule should be applied. The children are playing in a location with a long, low climbable stone fence. There are also bushes and trees. The play on the stone fence is about preparing for travelling with an ‘ambulance-train’. Anton, Sven, Ellinor and Fanny (lying across Ellinor’s knees pretending to be a ‘baby dog’) are observed in the following sequences of the play.

In the first play sequence (see ), there is a train to catch. The children have climbed upon the stone fence; the emplacement of their bodies initiates the gradual creation of an imaginative play-place, which escalates when they call another child to join the train. The child doesn’t come, but it’s clear that the vehicle will leave soon, as signalled by the stick, which is handed over with a ‘Take it, and then the train leaves’ and by gestures in the air to push imaginary buttons. Ellinor then starts a negotiation about wearing seatbelts. With both words and gestures, the children propose the rules they think should be applied: to wear or not to wear seatbelts. In this way, the seatbelt has a function: without being physically present; it’s turned into a resource in the children’s fantasy play. The seatbelt is part of the construction of this fantasy vehicle play, and present in the children’s imagination as part of their play-place. Thus, in their play, the children transfer the concept of the seatbelt from the bus – one spatial context, to the created play-place outdoors – another spatial context (cf. Massey, Citation2005). In this interpretive reproduction, the children are constructing meaning (cf. Corsaro, Citation2018) regarding the rule about seatbelts. When the train is close to leaving, Ellinor shows by her gesture and statement that she is putting a seatbelt on. This can be compared to when the engine in the bus is on: then the rule is that you must wear the seatbelt. Anton and Sven interpret the rule differently (see ).

All the children involved in the negotiation on the usage of seatbelts are dealing with an imagined seatbelt. Anton and Sven consider that the rule about the seatbelt – a rule very present in the mobile preschool – isn’t applicable; they shoot and destroy the material that Ellinor proposes in the play. Though, even if the play is transformed (a question about more coal comes up) the seatbelt remains present through a final gesture conducted by Ellinor.

Wearing seatbelts in an airplane – a reshaped play-place

Later, Hans and Anton are playing at the same location as in the example with the train. Hans has the spot where the driver sits. He is in ‘the cab’ – on a stone which is situated above the stone where Anton sits. The children successively transform the stone fence into another vehicle (see ).

What previously was an ambulance-train is now transformed into an airplane; the play-place is thus reshaped. The question of how to start the engine is negotiated; a small stick is transformed into and used as a key, and the children push imaginary buttons. The seatbelt is once again turned into a resource in creating a fantasy play; however, this time there is an agreement. The mobile preschool’s systematic work with safety on the importance of wearing a seatbelt whenever the engine is on is transformed, in what can be understood as an interpretive reproduction (cf. Corsaro, Citation2018), by the children: That it’s ‘not allowed to walk on the wing’ while the airplane engine is on is expressed by ‘when the airplane drives’. The children’s reasoning stresses a crucial cause of the rule: when the engine is on, they must wear seatbelts. This means that they cannot leave their seats to walk around, whether on the gangway of the bus or on the wing of the airplane. The play continues (see ).

A formulation of the fantasy play-place (cf. Massey, Citation2005) as spontaneous and very much improvised (cf. Evaldsson & Corsaro, Citation1998), as an unpredictable process (cf. Manso et al., Citation2017), may be interpreted in the children’s composing and mixing what is seen with new imagined events. In their exploring the play-place transforms. Through interaction, the children build on each other’s proposals. The product – a transformed widened play-place – is externalized with an imagined airplane stuck in a tree. It becomes very clear that the children in this situation are able to widen the play-place, both in fantasy and bodily (in contrast to the childreńs possibilities in Example 1), as they leave the stone fence to untangle the airplane from the bushes some distance away.

Discussion

This study contributes to research taking a relational view regarding children's place-making play in different preschool contexts. To understand the children's own novel formations of place I have formed the concept play-places.

In the children’s fantasy vehicle play, places are created (cf. Massey, Citation2005), and certain issues become visible: the usage of seatbelts and that vehicles can break down. These issues seem to be of importance to the children (cf. Löfdahl, Citation2002), and are crucial issues for the mobile preschool as well. Within the mobile preschool, the children experience everyday safety routines, such as the practice of wearing a seatbelt, and other issues regarding a preschool bus – as well as contrasting mutable spaces. In their fantasy play, the children are involved in meaning-making explorations. They perform what can be seen as collectively spontaneous improvization, and they broadly interpret (cf. Evaldsson & Corsaro, Citation1998; Manso et al., Citation2017; Sawyer, Citation1997) what it means to participate in a preschool conducted on a bus with a specific safety dimension. In this process, the children’s own novel events of place emerge – i.e. their formulations of different play-places within a mobile preschool (cf. Massey, Citation2005). In their collective fantasy play, mostly within the play itself (cf. Corsaro & Johannesen, Citation2007), the children shape, reshape and connect spaces in transformational processes. Thus, there’s ongoing negotiated alteration. That the children’s play-places emerge through their fantasy play practices (cf. Massey, Citation2005) aligns with earlier research that has shown that children, to make sense of the world, construct and transform their contexts (cf. Corsaro & Johannesen, Citation2007; Evaldsson, Citation2011; Schwartzman, Citation1978). In this article, I emphasize that play resources created by the children don’t just involve using toys and physical space. In a further articulation of how children can be viewed as using and transforming resources (cf. Änggård, Citation2009), by emphasizing the children’s agency, I suggest that the children innovatively transform the spaces of the bus into resources in their play. In place-making processes, the children connect and transform outdoor and indoor spaces into resources in play as well as create diverse mutable play resources such as drills, a steering wheel (transformed from a few modest open-ended objects) and imaginary seatbelts. In this way, through interpretive reproduction processes (cf. e.g. Corsaro, Citation2011), the children shape imaginative play-places and negotiate the meaning of different issues. Within their collective fantasy play, they go beyond physical boundaries to widen their places for play as they create imaginative extensive places. In this way, by their transformations of spaces of the mobile preschool, the children create their own formations of place (cf. Gustafson, Citation2009; Rasmussen, Citation2004).

The facilitating of play (cf. Kane, Citation2015) and children’s places (cf. Rasmussen, Citation2004) in the organization of the mobile preschool are crucial to the findings of this study. There were opportunities for the children to engage in place-making fantasy play both indoors and outdoors, and the furnishing of the bus and the stone fence could be used in creative ways. This finding can be compared with the emphasis in earlier research on open-ended objects that can be used in different ways by children (e.g. Änggård, Citation2009; Eriksson Bergström, Citation2013; Morrissey et al., Citation2017). In this case, however, the children engaged with a bus and a stone fence as if they were open-ended.

Children’s use of space can influence how space is understood by adults (Hacket, Citation2015), but this requires attentiveness. Close examination of children’s place-creating social interactions in fantasy play, in terms of how they move with their interpretive meaning-making (see Hacket, Citation2015) and use their voices (see Björk-Willén, Citation2012; Corsaro & Johannesen, Citation2007; Lodge, Citation1979), and in terms of what issues are processed (see Löfdahl, Citation2002), should be of importance in all kinds of preschool practices. In studying how the children engage with different spaces in play and create emerging places of their own, it can in itself induce possibilities for their contribution to culture (cf. Corsaro, Citation2011), and grant a higher tolerance towards children’s own places (cf. Rasmussen, Citation2004) and add to our understanding of the practices where the children are playing.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the children and staff within the mobile preschool where I conducted the fieldwork, Katarina Gustafson, Danielle Ekman Ladru, William A. Corsaro, Ann-Carita Ewaldsson, Polly Björk-Willén and the two reviewers for their comments on drafts of this article and the Swedish Research Council for financial support (grant number 2015-01260_3).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes on contributor

Carina Berkhuizen is a PhD student in pedagogy at Uppsala University, Department of Education, Didactics and Educational Studies and a lecturer at Malmö University, Department of Children, Youth and Society.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In addition to parks of different types, this means areas accessible inter alia because of the Swedish Right of Public Access; roaming the countryside in a responsible manner is everyman's right in Sweden (Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, Citation2019).

2 According to a mapping of mobile preschools, there were 14 municipalities with mobile preschools in Sweden in 2017, in total 42 buses (Gustafson et al., Citation2017).

3 In comparison to another version of mobile preschools, which occurs in Australia, where the concept means that a mobile teacher goes to, and gives support to, preschools in remote areas (see Nutton, Citation2013).

4 This means that the kind of play indoors, studied in this article, should be hard to find in all Swedish mobile preschools.

5 Synonym for fantasy play.

6 Presented in figures in this article.

References

- Änggård, E. (2009). Skogen som lekplats Naturens material och miljöer som resurser i lek [The forest as play-ground: Natural objects and environments as means for play]. Nordisk pedagogik, 29(2), 221–234.

- Änggård, E. (2010). Making use of ‘nature’ in an outdoor preschool: Classroom, home and fairyland. Children, Youth and Environments, 20(1), 4–25.

- Änggård, E. (2012). Att skapa platser i naturmiljöer: Om hur vardagliga praktiker i en Ur och Skur-förskola bidrar till att ge platser identitet [The construction of places in outdoor environments: About how everyday practices in an outdoor preschool contribute to places identities]. Nordisk barnhageforskning 2012, 5(10), 1–16.

- Björk-Willén, P. (2012). Being doggy: Disputes embedded in preschoolers’ family role-play. In S. Danby, & M. Theobald (Eds.), Disputes in everyday life: Social and moral orders of children and young people. Sociological studies of children and youth (Vol. 15, pp. 119–140). Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Corsaro, W. A. (2011). Peer culture. In J. Qvortrup, W. A. Corsaro, & M. Honig (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of childhood studies (pp. 301–315). Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Corsaro, W. A. (2012). Interpretive reproduction in children’s play. American Journal of Play, 4(4), 488–504.

- Corsaro, W. A. (2015). The sociology of childhood (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Corsaro, W. A. (2018). The sociology of childhood (5th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Corsaro, W. A., & Johannesen, B. O. (2007). The creation of new cultures in peer interaction. In J. Valsiner, & A. Rosa (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of socio-cultural psychology (pp. 444–459). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Corsaro, W. A., & Molinari, L. (2008). Policy and practice in Italian children’s transition from preschool to elementary school. Research in Comparative and International Education, 3(3), 250–265. doi: 10.2304/rcie.2008.3.3.250

- Ekman Ladru, D., & Gustafson, K. (2018). ‘Yay, a downhill!’: Mobile preschool children’s collective mobility practices and ‘doing’ space in walks in line. Journal of Pedagogy, 9(1), 87–107. doi: 10.2478/jped-2018-0005

- Eriksson Bergström, S. (2013). Rum, barn och pedagoger Om möjligheter och begränsningar i förskolans fysiska miljö [Space, children and preschool teachers – about possibilities and limitations in the physical environment of preschool] (Doctoral dissertation). Umeå: Umeå universitet.

- Evaldsson, A. (2011). Play and games. In J. Qvortrup, W. A. Corsaro, & M. Honig (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of childhood studies (pp. 316–331). Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Evaldsson, A., & Corsaro, W. (1998). Play and games in peer cultures of preschool and preadolescent children: An interpretative approach. Childhood, 5(4), 377–402. doi: 10.1177/0907568298005004003

- Gustafson, K. (2009). Us and them – children’s identity work and social geography in a Swedish school yard. Ethnography and Education, 4(1), 1–16. doi: 10.1080/17457820802703457

- Gustafson, K., & van der Burgt, D. (2015). ‘Being on the move’: Time-spatial organisation and mobility in a mobile preschool. Journal of Transport Geography, 46(June 2015), 201–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2015.06.023

- Gustafson, K., & van der Burgt, D. (2016). Lärande i staden: tidsrumsliga aspekter av en mobil förskolepedagogik, 2016–2019 [A citywide classroom: Time-space aspects of a mobile preschool pedagogy, 2016–2019]. Uppsala: Uppsala universitet.

- Gustafson, K., van der Burgt, D., & Joelsson, T. (2017). Mobila förskolan, vart är den på väg? Rapport från en kartläggning av mobila förskolor i Sverige april 2017 [The mobile preschool, where is it going? A report from a mapping of mobile preschools in Sweden April 2017]. Uppsala: Uppsala universitet.

- Hacket, A. (2015). Children’s embodied entanglement and production of space in a museum. In J. Seymour, A. Hacket, & L. Procter (Eds.), Children’s spatialities embodied, emotion and agency (pp. 75–92). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hellman, L., & Sunnebo, L. (2009). Mobil pedagogik – nya äventyr varje dag [Mobile pedagogy – new adventures everyday]. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Holloway, S. L., & Valentine, G. (2000). Childreńs geographies – playing, living, learning. London: Routledge.

- James, A. (2001). Ethnography in the study of children and childhood. In P. Atkinson, A. Coffey, S. Delamont, J. Lofland, & L. Lofland (Eds.), Handbook of ethnography (pp. 246–257). London: SAGE.

- James, A. (2011). Agency. In J. Qvortrup, W. A. Corsaro, & M. Honig (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of childhood studies (pp. 34–45). Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kane, E. (2015). Playing practices in school-age childcare: An action research project in Sweden and England (Doctoral dissertation). Stockholm: Stockholm University.

- Lillvist, A., & Sandberg, A. (2015). Play in a Swedish preschool context. In J. L. Roopnarine, M. M. Patte, J. E. Johnson, & D. Kushner (Eds.), International perspectives on children’s play (pp. 175–186). Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill Education.

- Löfdahl, A. (2002). Förskolebarns lek en arena för kulturellt och socialt meningsskapande [Pre-school children’s play – arenas for cultural and social meaning-making] (Doctoral dissertation). Karlstad: Karlstads universitet.

- Lodge, K. (1979). The use of past tense in games of pretend. Journal of Child Language, 6, 365–369. doi: 10.1017/S0305000900002361

- Manso, S., Ferreira, M., & Vaz, H. (2017). Children’s play events as improvisational choreographies. International Journal of Play, 6(2), 135–149. doi: 10.1080/21594937.2017.1348314

- Massey, D. (1999). Space-time, science and the relationship between physical geography and human geography. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 24(3), 261–276. doi: 10.1111/j.0020-2754.1999.00261.x

- Massey, D. (2005). For space. London: SAGE.

- Mayall, B. (2002). Towards a sociology for childhood – thinking from children’s lives. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Morrissey, A.-M., Scott, C., & Rahimia, M. (2017). A comparison of sociodramatic play processes of preschoolers in a naturalized and a traditional outdoor space. International Journal of Play, 6(2), 177–197. doi: 10.1080/21594937.2017.1348321

- Nutton, G. D. (2013). The effectiveness of mobile preschool (Northern Territory) in improving school readiness for very remote indigenous children. (Doctoral dissertation). Darwin: Charles Darwin University.

- Qvortrup, J., Corsaro, W. A., & Honig, M.-S. (Eds.). (2011). The Palgrave handbook of childhood studies. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Rasmussen, K. (2004). Places for children – children’s places. Childhood, 11(2), 155–173. doi: 10.1177/0907568204043053

- Sawyer, R. K. (1997). Pretend play as improvisation conversation in the preschool classroom. New York: Routledge.

- Schwartzman, H. (1978). Transformations: The anthropology of children’s play. New York: Plenum Press.

- Sverige, S. (2018). Läroplan för förskolan Lpfö18 [Curriculum for the Preschool Lpfö18]. Stockholm: Skolverket.

- Swedish Environmental Protection Agency. (2019, December 20). This is the right of public access. http://www.swedishepa.se

- Vetenskapsrådet. (2017). God forskningssed [Good research practice]. Stockholm: Vetenskapsrådet.

- Vuorisalo, M., Rutanen, N., & Raittila, R. (2015). Constructing relational space in early childhood education. Early Years: An International Research Journal, 35(1), 67–79. doi: 10.1080/09575146.2014.985289

- Vygotsky, L. S. (2004). Imagination and creativity in childhood. Journal of Russian and East European Psychology, 42(1), 7–97. doi: 10.1080/10610405.2004.11059210