ABSTRACT

The French existentialist philosopher, Simone de Beauvoir, long ago signalled the potentially empowering force of outdoor exercise and recreation for women, drawing on feminist phenomenological perspectives. Feminist phenomenological research in sport and exercise, however, remains relatively scarce, and this article contributes to a small, developing research corpus by employing a feminist phenomenological theoretical framework to analyse lived experiences of running in ‘public’ space. As feminist theorists have argued, such space is gendered and contested, and women’s mobility remains constrained by fears of harassment and violent attack. Running also generates intense pleasure, however, and embodied empowerment. Drawing on findings from two separate but linked automethodological running research projects, here I explore salient and overlapping themes cohering around lived experience of pleasure and danger in both urban and rural spaces.

Introduction

Within the sociology of sport, women’s sporting embodiment has formed the focus of feminist analysis via a variety of theoretical perspectives, particularly from the 1990s onwards (e.g. Esmonde Citation2019; Hall Citation1996; Hanold Citation2010; Markula Citation2003; McGannon et al. Citation2019). Initiated by the ground-breaking work of French philosopher, Simone de Beauvoir, feminist phenomenological research is gradually developing in our field, particularly since Iris Marion Young (Citation1980/Citation1998) thought-provoking study, ‘Throwing like a girl’. This literature examines women’s sporting involvement in, for example: fitness gyms (Clark Citation2018), boxing (Rail Citation1992), climbing/mountaineering (Chisholm Citation2008; Tulle Citation2022), Māori waka ama (canoe) paddling (Liu Citation2021), cross-country running (Allen-Collinson Citation2011a; Allen-Collinson and Jackman Citation2022), and physical activity generally (Berry et al. Citation2010; Del Busso and Reavey Citation2013; Liimakka Citation2011). To date, however, this theoretical framework has rarely been employed in addressing women’s embodied experiences of running vis-à-vis spaces of pleasure and danger (Allen-Collinson Citation2011a).

It is timely, therefore, to address this powerful, but often uneasy and challenging theoretical nexus, focusing here upon a woman’s running embodiment in outdoor public spaces. Employing the potent combination of feminism and phenomenology in a form of existential feminist phenomenology (hereafter shorted to ‘feminist phenomenology’), in conjunction with findings from two automethodological research projects (described below), I examine my lived experience of being a running-woman in putative ‘public’ space. While such running is lived in the everyday sense, it is also ‘lived’ in the phenomenological sense of being consciously examined and reflected upon. The experience of public space is also socially structured and contoured by what feminist researchers have noted as women’s lack of an undisputed right to occupy that space (Roper Citation2016; Vera-Gray and Kelly Citation2020; Wesely and Gaarder Citation2004). To address some of these experiential issues, I first provide a brief depiction of feminist phenomenology, before delineating the research projects from which my data derive. Salient themes are then portrayed in relation to my lived-body experiences of the pleasures and dangers of being a running-woman in a variety of public spaces, both rural and urban.

Feminism and phenomenology: a potent nexus

Modern phenomenology, founded in the 19th century by the philosopher, Edmund Husserl, now constitutes a wide-ranging, complex, and multi-stranded perspective, with very different ontological and epistemological positions underlying its various traditions (see Allen-Collinson Citation2009 for a sports-related overview). Existentialist phenomenology, and the writings of the French existentialists, Simone de Beauvoir and Maurice Merleau-Ponty, have particularly piqued the interest of feminist theorists (e.g. Butler Citation2006; Olkowski and Weiss Citation2006; Weiss Citation2000). Whilst trenchant critiques have been levelled at traditional forms of phenomenology for its lack of analytic attention to difference, including embodied differences relating to gender, sexuality, ethnicity, dis/ability, and so on, feminist phenomenology explicitly recognises difference, and the social-structurally shaped, historically-specific, and culturally-situated nature of human experience (Allen-Collinson Citation2011a). Phenomenological insights from Merleau-Ponty’s oeuvre have been employed and adapted inventively by feminist scholars (e.g. Butler Citation2006; Fielding Citation2000; Olkowski Citation2006). As Kruks (Citation2006, 27) argues, despite sometimes sexist assumptions regarding the pre-personal (for which read ‘male’) body, Merleau-Ponty can help illuminate significant aspects of human existence, including the exploration of gender (and other) differences that he did not himself address.

Germane to the current article, perception is a central concern for Merleau-Ponty (Citation2001), and described as an active, creative receptivity and reciprocity between mind-body-world. In his later, unfinished writings, Merleau-Ponty (Citation1968) argues for our existential unity with the ‘flesh’ (the French, chair) or fabric of the world, and the ways in which we can experience phenomena at a deeply corporeal, pre- (or perhaps ‘beyond’) linguistic level. Furthermore, Merleau-Pontian phenomenology and feminist theory pursue a shared interest in corporality, and corporeally-grounded experience (Alcoff Citation2000; Butler Citation2006; Olkowski Citation2006), well-suited to generating insights into experiences of sport, exercise and physical activity (Hockey and Allen-Collinson Citation2007; Samudra Citation2008), and the lived-space of these activities.

Before proceeding to delineate the research projects at the heart of the current analysis, I first include a brief word about the phenomenological method, which is not a ‘method’ in the traditional sense of a research procedure, but more a Weltanschauung or worldview: a questioning orientation to the world, requiring the researcher’s openness and attentiveness to phenomena. Indeed, lively debates flourish as to how to undertake phenomenological or phenomenologically inspired research (e.g. Allen-Collinson Citation2011b; Bluhm and Ravn Citation2021; Finlay Citation2009). Drawing on Husserl (Citation2002) form of descriptive phenomenology, many phenomenologists have as a core aim to ‘go back to the things themselves’ (zu den Sachen selbst) to describe core structures or patterns of experience of a phenomenon, without resort to undue abstract theorisation. The aim is to arrive at the phenomenon/a afresh, as far as possible devoid of presuppositions. In this endeavour, phenomenological researchers attempt to identify and thematise their existing knowledge and assumptions about a phenomenon, via a process of epochē (from the Greek ‘to keep a distance from’); a form of bracketing.

The research projects

Congruent with automethodological approaches, it is important to provide some background information regarding my own running biography, to situate myself as researcher-participant. I have been a non-élite distance runner for over 35 years, with a running career that encompasses more ‘serious’ running, demanding a sustained commitment to training six to seven days a week, often twice daily, through to my current, more restricted running, undertaken once-a-day for only five days per week. Now in my early 60s and contending with an osteoarthritic foot, and longstanding ‘dodgy’ knees, nowadays I run predominantly on the softer, more forgiving surfaces of cross-country, to avoid high-impact tarmac, asphalt and concrete.

Here, I use the term ‘cross-country’ to describe multi-terrain running in the countryside, the vast majority of which is off-road, and usually off-pathways or established trails. This form of running involves ‘crossings’ over and within a wide array of terrain and landscapes, from fells and mountains (e.g. Atkinson Citation2010; Nettleton Citation2015), to peaty, mossy, boggy moorland, rough pastureland, and muddy ploughed fields. As so evocatively described by Atkinson (Citation2010), fell running is usually undertaken in expansive, rugged, and (often) inclement highland or mountain areas, such as the English Lake District. Cross-country running shares some commonalities with fell running in that those runners who opt for rougher terrain may find themselves not only running, but clambering, scrambling, slipping, sliding, and stumbling over almost any form of terrain, including river- and stream-crossings, albeit not at the elevations encountered in fell running.

As Powis (Citation2019) notes, autoethnography has proved highly effective in exploring the lived experience of sport by drawing on the researcher’s own first-hand, sensory, embodied experiences. Autoethnography, and its phenomenological sibling, autophenomenography, are highly advantageous in providing access to what can be fleeting and nebulous emotions and feelings often so challenging to elicit from others (Allen-Collinson Citation2011a; Sparkes Citation2009). Autoethnography investigates the dialectics of subjectivity and culture via the exploration of an author-researcher’s experiences as a member of a distinctive social group or ethnos (Allen-Collinson Citation2013). Whilst autoethnographies are now widespread within sport and exercise domains, autophenomenographies are perhaps less well-known, but have been explored in this journal (Allen-Collinson Citation2009, Citation2011b, etc) Autophenomenography is analogous to autoethnography in many ways, but divergent in that researchers focus primarily on their own lived experience of phenomena rather than on their experiences as a member of a social group/ethnos, as would be the case in autoethnography (see Allen-Collinson Citation2013; Lamont Citation2020). There is, however, inevitable imbrication and blurring in these different aspects. Furthermore, feminist phenomenology directly acknowledges and explores social-structural and socio-cultural influences on corporeal experience (Allen-Collinson Citation2011a; Chisholm Citation2008; Fisher and Embree 2000).

The two running research studies on which I draw comprised: Project 1: an autoethnographic and autophenomenographic study of a woman’s distance- and cross-country running; and Project 2: a duoethnography of distance running, undertaken in collaboration with Dr John Hockey, my running-partner. Institutional ethical approval was not required for autoethnographic research at the time of commencing these projects. In Project 1, I maintained a running-research diary, initially for a period of almost three years, to record in detail my embodied experiences of daily training sessions. Since the initial tranche of data collection, I have subsequently continued to keep a training diary but more sporadically. During both spans of research time, I have made field notes (written post-run), and more recently included audio recordings made on a smart phone, usually immediately after the run, but sometimes during the run itself – when demands of terrain and training-session permit. I also, though less frequently, take photographs on the smart phone, principally as reminders of location, and of weather and environmental conditions, to assist in the analytic and reflective process. In the duoautoethnographic study (Project 2), which was undertaken over a two-year period of injury rehabilitation, as researcher-participants we systematically recorded, individually and jointly, our daily training and rehabilitation. Data were recorded as written field notes and via micro tape-recorders. Given the temporal pressures of incorporating training sessions into long workdays, it was usually not possible to compose extended field notes, but our tape-recordings generated substantial transcriptions.

Reflexivity and (sociological) bracketing

In both projects, and as an integral element of the research, I/we engaged in sustained ‘embodied reflexivity’ (Burns Citation2003) by subjecting to challenge and questioning the impact of our running bodies on the attitudes, meanings, beliefs and running knowledge we held, and which we also generated via our bodily ways of knowing. Thus, in Project 2, both researcher-runners acted as ‘critical friends’ (Smith and McGannon Citation2018) as we challenged each other’s beliefs and constructions of knowledge, to enhance reflexivity. As a feminist sociologist, I fully acknowledge the impossibility of achieving (or indeed pursuing) complete epochē, but nevertheless I make sustained efforts to identify as much as possible my assumptions and tacit beliefs about women’s distance running, in that I seek to thematise and scrutinise such beliefs and presuppositions throughout the research process (see also Allen-Collinson Citation2009, Citation2011b; McNarry, Allen-Collinson, and Evans Citation2019). I thus sought to sustain heightened reflexivity primarily by means of conversations with insiders and outsiders to the distance-running community, where these individuals acted as ‘critical friends’ (Smith and McGannon Citation2018), questioning and challenging my ideas and assumptions about being a running woman. I also read (and continue to read) a selection of studies focussed on cognate domains, such as fell running (Atkinson Citation2010; Nettleton Citation2015) and marathon running (e.g. Lev Citation2019, Citation2021; Ronkainen, Shuman, and Xu Citation2018), and also on very different sporting cultures such as boxing (Nash Citation2017; Woodward Citation2006) to compare accounts of sporting embodiment, including ‘intense embodiment’ experiences (Allen-Collinson and Owton Citation2015; Ravensbergen Citation2020).

Data analysis

In Project 2, data analysis was originally undertaken via a form of reflexive thematic analysis (RTA, see Braun and Clarke Citation2019), but subsequently we returned to the raw data to subject these to an analytic process inspired by Giorgi (Citation1997) phenomenological method. RTA was initially chosen (although not termed as such at the time of undertaking Project 2) given its coherence with our interpretivist paradigm, autoethnographic approach, and our commitment to continual ‘reflective and thoughtful engagement with the data’ and with the analytic process (Braun and Clarke Citation2019, 594). To enhance reflexivity, in addition to our individual training/research logs, we also maintained a collective ‘analytic log’ where we challenged each other regarding our presuppositions about distance running, debated emergent concepts and theorisations, recorded our emotional oscillations during the research process, and generally tried to subject to critical evaluation the impact of our individual and joint positionality on the whole research process (see also McNarry, Allen-Collinson, and Evans Citation2019). As Bluhm and Ravn (Citation2021) note in their study of runners, it is productive for phenomenological insights to be applied in the elucidation and analysis of phenomena, even when data have been collected by qualitative rather than phenomenological methods. This is what we subsequently (years later) did in seeking a more phenomenologically suited approach to data analysis, for which Giorgi's (Citation1997) empirical phenomenological approach was employed. In Project 1, an autophenomenographic approach was used from study inception, to record and analyse my experiences as a running woman. Here, I adhered quite closely to Giorgi (Citation1997) guidelines for undertaking phenomenological research, but departed from these in two salient ways: first, I undertook the study from a feminist-sociological, rather than a psychological perspective; second, rather than assembling descriptions from a range of participants, I was both researcher and participant (the ‘auto’ element in autophenomenography), using detailed descriptions of my own embodied experiences. This ‘auto’ approach has been employed by other phenomenologically oriented researchers such as in Finlay (Citation2003) powerful account of her lived experience of multiple sclerosis.

With this caveat in mind, I followed Giorgi (Citation1997) guidelines with regard to: i) the collection of concrete descriptions (field notes primarily) from my auto/insider perspective; ii) the adoption of the phenomenological attitude, including making best efforts to thematise my existing assumptions about being a running-woman running in public space; iii) undertaking initial impressionistic readings of these descriptions to gain a feel for the overall set; iv) more in-depth (re)reading of descriptions as part of a lengthy process of data-immersion and familiarisation, in order to code data and then identify sub-themes and key themes; v) free imaginative variation, where I sought out the core or ‘essential’ characteristics of the phenomenon. This latter Husserlian phenomenological process involves creatively and imaginatively varying certain elements of the phenomenon under study to consider a range of possible meanings by, for example, approaching the phenomenon from imagined different positions (e.g. from a male perspective for a female researcher). This process helps ascertain whether the phenomenon under study remains identifiable after such imagined changes (see also Turley, Monro, and King Citation2016).

So, whilst as a sociologist, I fully acknowledge that complete bracketing is never possible or indeed desirable, nevertheless I consider that engaging in critical self-reflection and seeking to identify tacit, often long-held, assumptions regarding familiar phenomena, constitutes good research practice generally. In the case at hand, it was an activity with which I was highly familiar: running in public space. The key findings, cohering around the pleasures and dangers of such running, are analysed below in relation to both urban and rural running. Whilst both domains hold distinctive hazards and dangers, both also offer their own particular pleasures. A caveat should be mentioned at this point: the majority of my training runs are routine, unremarkable and uneventful, in contrast to experiences of the kinds of dangers and (relatively intense) pleasures portrayed below. These more remarkable or ‘marked’ runs are noteworthy precisely because they challenge my ‘normal’, everyday running experiences (which latter are described elsewhere, e.g. Allen-Collinson Citation2008). The ‘remarkability’ of these pleasure/danger running encounters thus assists with heightening reflexivity and with engagement in the phenomenological epochē.

Pleasure/danger nexus

As Blomley (Citation2009) notes, whilst public spaces are presumptively open to everyone, in lived experience they often become expressive of unequal distribution of values and power. Furthermore, the ‘public’ is not a homogenous body with equal rights of access and participation. The political and strategic social structuring of public space has been subjected to extensive geographical analysis by Lefebvre (Citation1977), for example, and feminist researchers have long highlighted the ways in which access to, and participation in public space are structured by gender and other key variables such as ‘race’/ethnicity (e.g. Gimlin Citation2010; Roper Citation2016; Springgay and Truman Citation2022), whether in urban (e.g. Brockschmidt and Wadey Citation2021; Gardner Citation1995; Roper Citation2016) or rural (e.g. Allen-Collinson Citation2008) spaces. From the data, the paradoxes of running in and through public space were identified: negative structures of experience included verbal and physical harassment, and (rare) actual physical attack. Pleasurable experiences far outweighed those relating to danger, however, especially when running in rural areas, although, as will be examined below, countryside running holds its own distinctive dangers. I move first to the urban environment.

Civic (in)civilities

There is a considerable history, growing in force since the 1970s in particular, of women’s campaigns such as ‘Take Back the Night’ (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Take_Back_the_Night_organization) and ‘Reclaim the Night’ (http://www.reclaimthenight.co.uk) seeking to highlight women’s right to walk city streets (and indeed everywhere) safely and without risk of harm. In more recent years, the #MeToo campaign against sexual harassment and assault has raised awareness of sexual assaults against women, encouraging survivors to come forward with their personal accounts. Running in public urban space can undoubtedly confront women (and men also in some contexts) with threatening encounters, most often with male others (Allen-Collinson Citation2008; Brockschmidt and Wadey Citation2021; Gimlin Citation2010; Roper Citation2016; Vera-Gray and Kelly Citation2020). During many urban runs, male strangers – men and teenage boys predominantly – have lunged towards me, pushing, prodding, and grabbing at various parts of my anatomy. The following field note from Project 2 is illustrative of many analogous occurrences of verbal and (‘mild’ in this instance) physical harassment:

… we were running down the high street on a busy shopping day in town. X diverted off to nip into the gents’ toilet, so I jogged around whilst waiting for him. Suddenly felt someone brush against me and comment, quite loudly: ‘Fantastic arse, Love’. Before I have chance to utter a withering rejoinder, he is vanishing off down the pavement, turning around to smile and nod, presumably in what he considers an appreciative fashion. I feel the heat and colour rise to my skin, seeing red is indeed the metaphor: angry red suffuses my body at that instant. The adrenalin surge lightens my aching legs and I resume the run at a bursting sprint – at least for the first few minutes. Only when my pace slows sufficiently does X catch up with me and I have chance to explain my fury at the distasteful encounter. (Project 2)

At times, as indicated in the above field note, and resonating with both the phenomenology of anger (Thomas, Smucker, and Droppleman Citation1998) and with other research on women runners (e.g. Roper Citation2016), such harassment evokes in me strong feelings of anger, outrage and fury, which are ‘lived’ at an intense, corporeal level, engendering the kinds of somatic reactions described above. With regard to such verbal and physical harassment, Smith (Citation1997) and Roper (Citation2016) both delineate the strategies runners use to deal with various forms of harassment and even assault, while training in public places, such as seeking to avoid attracting attention by selecting ‘low key’ running gear, even whilst highly cognisant that this should not be their responsibility. Whilst streamlined, snug-fitting clothing often offers greater functionality for my running body, it has (mostly in my younger days) garnered much unwanted male attention and comments. My clothing compromise is usually to opt for streamlined, functional clothing, but simultaneously to seek a degree of anonymity and interactional protection via sunglasses and a cap pulled low. Relatedly, from a feminist-phenomenological perspective, the corporeal distinctiveness of women runners’ breasted bodies means that we often use sports bras and other garments to flatten down and restrain the fleshy expansiveness of breasts, to create a more ‘efficient’, dynamic, and comfortable running body. As Young (Citation1992) evocatively portrays, women’s breasts can form a key structure of our being-in-the-world, and during exercise are liable to move considerably. For many women runners, even those who are not especially full-breasted, such movements can be uncomfortable or painful during the action of running, making the sports bra an essential item of running gear/technology (see also Brice, Clark, and Thorpe Citation2021 for a feminist-materialist perspective). I well recall my early days of running when my fuller-curved body required donning two sports bras, and sometimes a leotard on top, to make running more comfortable.

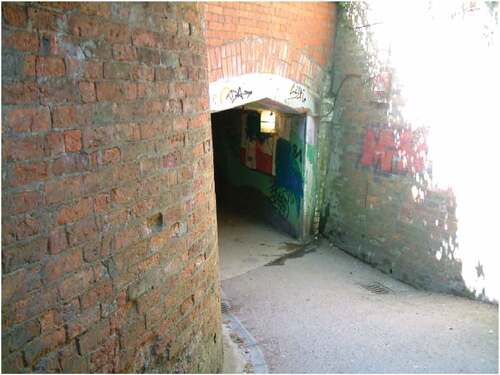

Careful selection of running clothing is not of course sufficient to prevent women runners from being harassed, attacked or worse. Much research has highlighted how women often become highly sensitised and attuned to places and contexts that harbour risk of verbal, and particularly physical attack (Roper Citation2016; Smith Citation1997; Wesely and Gaarder Citation2004). This results in the deployment of a range of avoidance strategies, including staying away from places where participants consider they would enjoy running, but where they fear high vulnerability to attack, such as wooded areas in urban parks (Roper Citation2016). Whilst I do myself at times skirt around such spaces, sometimes they are difficult to avoid on certain running routes. Then I run warily, senses on full alert, as I negotiate dark, narrow alleys, underpasses, and back streets, and even when passing pub entrances where lewd, sexist comments and grasping hands can accost women runners. One such place, recorded in Project 2, is an underpass (see ) beneath a busy road, which links two areas of the same urban park, with steep brick-built walls to either side before a descent into a dark and dank brick tunnel.

Although the underpass is only about 20 metres in length, the sudden plunge into its dimly lit, foetid depths always generates an adrenaline surge, especially when running at night:

It’s a wild, windswept night and I don’t want to wait for ages trying to cross the main road. Hesitating before plunging into the bowels of the dirty, dank underpass, I dither on the spot momentarily, weighing up the potential costs. But the November wind is whipping around me, pushing me forward. Holding my breath, partly to avoid inhaling the rancid air, but more to listen out for sounds of danger, I plunge into the foetid tunnel. Senses on max, sprinting through! Even as I begin the ascent out of the depths, the bend of the slight uphill can hide men lurking with bad intent … Only when I’m safely out on the grass lawns of the park, do I ease up and begin to breathe properly. Made it. (Project 2)

Whilst urban running has its hazards and dangers as portrayed above, it can also provide more secure and familiar public space where the comforting presence of other people, and particularly other runners or exercisers, can generate feelings of safety in numbers and reduce the likelihood of harassment or attack. Furthermore, many women runners and exercisers, despite their fears, refuse to be dissuaded from running in their chosen places. As Roper (Citation2016) discovered in her research on women recreational runners, many engage in acts of resistance by continuing to run outdoors (see also Koskela Citation1999) despite their anxieties, responding with boldness and defiance rather than fear. For me, running in urban (and rural) areas gives me a sense of speed (albeit declining with age) and power, as I feel more able to elude and escape male attention when running at pace than when walking. In contrast to feelings of bodily vulnerability, for the most part, my running generates feelings of embodied strength, power, dynamism, of being capable and ready-for-action. But these feelings are of course highly context-dependent. In her work on women’s participation in triathlon, Granskog (Citation2003) argues for the importance of finding spaces where women can attain a sense of personal empowerment, especially in societies that too often discount women’s capacities and strengths. Commensurate with her analysis, I too revel in feelings of lived-body empowerment, strength, and capability, of putting my body to work as opposed to the ‘head-work’ that (pre)occupies my working days. The mind-body-world nexus, so fundamental to existentialist and feminist phenomenology, is brought to the forefront of my consciousness as I seek to balance mind and body, and begin to feel the bodily pleasures of the urban outdoors:

Nearly 3 weeks solid of marking. My legs and arms are heavy from it, neck and shoulders rigid, strained, taut to breaking. Eyes red and sore. It’s going to be a hard run tonight, I fear. But, just a few minutes into my stride and the navy-dusk wind is cutting away the work smog, sloughing off the grey skin of the working day. I am being cleansed. I am back. I am back in-body after a day of attempted body denial, and enforced focus on the headwork. Quads surge forwards, muscles strong and bulking, pushing against tracksters, abs tighten and flatten against the chill wind as I begin to up the pace. Power surges through me …

Having considered some of the hazards and dangers, along with pleasures, of running in and through the urban environment (see also Cook, Shaw, and Simpson Citation2016; Gardner Citation1995; Roper Citation2016), I now move out of the town-and-city environment and head into my preferred running-scape of the countryside.

Rural (re)treats

Whilst the risks and dangers of women’s running and exercising in urban areas have been relatively well-documented as noted above, the specific hazards of rural running are of equal import to those women who undertake their running in countryside or park locations, particularly when running solo (Jorgensen, Ellis, and Ruddell Citation2013). The countryside, and especially places of relative rural isolation, harbour distinct challenges, such as: distance from other people and from sources of help, social and physical support, challenging and hazardous terrain such as moors and screes, and possible encounters with farm or wild animals, in addition to the mercurial weather conditions of the UK, especially at higher elevations such as on fells and mountains. The ‘great outdoors’ beyond the confines of town and city is, however, an intrinsic and treasured component of my running, including being-in and being-with all the elements (Allen-Collinson and Jackman Citation2022; Allen-Collinson et al. Citation2019). I am happy to follow de Beauvoir’s (Citation2010-1949) exhortation that women go out and face the elements. For me, that includes battling against vicious, cutting winds, stinging hail, or fierce pelting rain, sinking into fresh glinting snow, glistening in beating summer sun, coursing over firm, salt-crusted sand, or traversing eerie fields brushed with silvery moonlight. Resonating with Merleau-Ponty (Citation1968) portrayal of the chiasmic intertwining of body-and-world, my lived-body merges and braids with the elemental world as a fundamental structure of my running experience. As I run through mist and fog, for example, the damp air enters my lungs and subsequently the oxygen moves into my bloodstream. Analogously, scents and aromas of the countryside carried on the air enter my nasal cavity, and can evoke strong olfactory memories, as in the following field note from a Devon riverside run:

It’s a glorious, gilded May day, and as I head down suburban streets to the river meadows, the warmed, sweet scent of cut grass suddenly meets me, taking me back to those long, summer-haze holiday afternoons as a child, with all the family sitting out in the back garden in deckchairs, cricket on the radio, a tractor busy somewhere in a distant field, and the drone of a light aircraft overhead. My memory mind travels, and a long section of the pathway goes missing in my running mind. (Project 1)

The sensory pleasures of the olfactory dimension have been relatively under-researched in the context of sport and exercise (Hockey and Allen-Collinson Citation2007; Sparkes Citation2009), but as highlighted in the above extract, smell has the power not only to affirm the intensity of our mind-body involvement in the sporting present, but also to evoke memories of times past, including the confirmation of sporting identity via sensory memories.

Other sensory pleasures of rural running combine multiple sensory modalities, commensurate with Merleau-Ponty (Citation2001, 221) observation that rarely do we experience one sense in isolation. Our lived experience is thus largely synaestheticFootnote1 in that multiple senses operate in combination. Such synaesthesia was identified in the following field note from Project 1 where visual and auditory pleasures combine with a sense of rhythm and timing to produce an experience of ‘flow’ (Jackman et al. Citation2021) where my running mind-body is in harmony with both rural landscape and (MP3-generated) soundscape:

One of those rare ‘in the moment’ runs tonight. Glorious sunset down by the river, great rhythm, my strides just eat up the ground. Whole sections of the route have gone missing (recalls an earlier fieldnote from a different place, a different time) as John Bonham’s great tree trunk sticks beat out the rhythm. Machine-gun the pace. Perfect rhythm, perfect timing. Flow. Breathing and beat in synchronicity. As aquamarine finale of sunset darkens to indigo, as the dying Pagey riffs fade away, I walk the last few steps down the path to my front door. Fade out. Synchronicity. (Project 1)

A further dimension of rural running that often engenders feelings of pleasure, joy and also privilege, is encounters with other animals, both wild and domesticated. Although there is not the scope to address this aspect in detail here, the pleasures of human-animal rural encounters can be intense and awe-inspiring. Whilst there are undoubtedly hazards of encountering animals in the countryside (including almost treading on an adder in French woodland, and being knocked from behind by a headstrong wild Dartmoor pony), many more pleasurable instances were identified in the data from both projects. Brief encounters with hares and rabbits, sudden meetings with moorland birds, fleeting glimpses of mice, voles, stoats and weasels, flypasts by skeins of geese and other wildfowl, and rare sightings of birds of prey, all bring pleasure and delight. Memorable moments of such inter-species intercorporeality or intercorporéité in Merleau-Ponty’s terminology (Merleau-Ponty Citation1964, Citation1968) are exemplified by a field note recounting a rural riverside run, intercorporeally shared with wild swans:

… heading out along the riverside … the long shadows are beginning to creep towards me, but the sun still catches my upper limbs to impart fading evening warmth. Now, suddenly the air behind me thickens and throbs. Then, with the muscular beat of powerful white wings and mewling constantly to each other, two great swans sink heavily downwards towards the river. Slowly, I look over to my left to watch my companions, necks outstretched, huge wings almost too slow to hold their bodies in mid-flight as they draw down alongside me at head height, to follow the river. Heart and wingbeats synchronise as we three run-fly together along the glistening river. For a wonderful, foolish, glorious moment, I feel flying. (Project 1)

Whilst encounters with wildlife primarily generate pleasure, even joy, human encounters out in more isolated rural areas can prove problematic, even threatening, for women-runners training alone. A field note relating to an early evening solo run testifies to my sensitivity to the potential dangers of relatively isolated areas, combined with my prior lived experience of analogous encounters in rural places:

Out along the river meadows, quite some way from the city and approaching the weir. Suddenly out of the blue, a red pick-up truck is hurtling its way across the field towardss me. Had spotted the truck previously careering across the fields, but within sight and earshot of dog-walkers and others. Now there is no one in sight, and the houses bordering the river are some way off on the other bank. Is that a shot gun sticking out of the open passenger window? [It’s a farming area where guns are common.] I catch male voices drifting towards me on the evening air. Heart pounding in my ears now. Try to steady breathing, better to concentrate. The truck is still approaching down the grassy track, bumping and swaying. I up the pace, pull down my baseball hat firmly and set my jaw sternly. I will my body harder, leaner, tauter, try to look focussed and ‘don’t mess with me’. Not for the first time, I wish my slight, 5’3” (1.6 m) runner’s body were somewhat more imposing. Suddenly, breath-catchingly, the truck veers off the track a few metres in front of me. I hear loud male voices and a radio blaring. Heart still pounding out time. Just in case, I up the pace to get out of the danger zone. (Project 1)

The above instance illustrates the role of prior lived experience in configuring how we perceive a situation, consonant with phenomenological perspectives. Added to such experience is extensive socialisation into gendered constructions of space and place where often ‘feelings of vulnerability and danger inform women’s geography of fear’ (Wesely and Gaarder Citation2004, 648, drawing on Valentine Citation1989). Isolated rural spaces are often deemed too dangerous and ‘out of bounds’ for women, and particularly for a lone woman. Also commensurate with phenomenological insights, my heightened sensitivity to, and awareness of danger is often felt at a deeply corporeal and sometimes visceral level, with elevated pulse rate, hammering heart, a tightening of abdomen, a hypersensitivity of skin, and shallow and/or quickened breathing:

Decided to take the bracken route down the moor to the track, but as I enter the head-height, dense bracken, I feel hemmed in, trapped, I can’t see what’s around the corner, who might be lurking at the path sides. My breath catches, holds, ears straining for any sound, goose pimples catch the moor breeze, trying to quieten my heartbeat so that I can hear … probably just sheep. I have to walk some of the way, the path is too steep, too friable for running, but I’m light and primed for flight as any moorland creature. Hit the open space with relief. (Project 1)

Whilst the above field note relates to an extended section of moorland running on the expansive area of Dartmoor in rural Devon (UK), even short sections of rural woodland (see ), not far from habitation and other people, can harbour dangers of potential confrontation and attack, as similarly noted by the women-runners in Roper (Citation2016) study of urban park running. Analogously, dense, dark woodland requires particularly acute sensory attention when I’m running solo:

There’s a short section of dense, dark pine woods between two lovely open field sections, both of which are great under foot, being drier than much of the surrounding land, with good drainage. The woods are spooky though, very dark, sombre and silent, with densely planted, high pine trees affording barely any light. Even in winter sunlight, night falls early afternoon in the woods. Whenever running solo, I remove any sunglasses, hood or snood that might inhibit vision or hearing, as I plunge into the green darkness, scanning left to right warily but quickly as I almost sprint across the pine-needled floor to the light at the end of the pine-tree tunnel. Once the daylit safety of the open field is reached, I feel my shoulders relax, heartbeat steadies and I breathe again. (Project 1)

The above findings demonstrate some of the key structures of my lived experience as a woman who habitually undertakes her running (often solo) in ‘public’ spaces – both urban and rural. From a feminist-phenomenological perspective, de Beauvoir (Citation2010-1949) long ago signalled the empowering force of outdoor recreation and exercise for women, whom she exhorted to battle against the elements, take risks, and go out for adventure. Battling the elements, taking (calculated) risks, and being in the outdoors constitute core elements in my own lived experience of running.

Concluding comments

The findings portrayed above contribute to extant feminist-phenomenological research, by examining the dialectics of pleasure and danger in a specific lifeworld of distance and cross-country running. This is an under-researched domain within feminist phenomenology, but one which can provide rich terrain for the application of its powerful theoretical insights to women’s sporting and physical-cultural embodiment. For me, the tensions between the considerable constraints of social-structural forces, and the potential of women’s social and corporeal agency, coalesce powerfully in my own embodied experiences of running. This nexus is often ‘lived’ at a deeply corporeal level, as illustrated by bodily reactions to instances of pleasure and danger delineated above. It is endlessly fluctuating and negotiated as I traverse the public spaces of my running routes. As Gardner (Citation1995) highlights, when women in public spaces feel vulnerable to unpredictable invasions of self, ranging in severity from objectification to violent crime, this strongly reinforces a patriarchal gender order by challenging women’s presence in this space. For me and for the women runners with whom I have trained and discussed these issues, most of our runs are routine, unremarkable and uneventful with regard to dangerous encounters. Nevertheless, I/we fully acknowledge that verbal and physical harassment, even assault, are still much too common experiences for women runners (Gimlin Citation2010; Roper Citation2016; Smith Citation1997). In contrast to feelings of vulnerability to attack, for the most part my running generates feelings of empowerment, consonant with research on women runners generally (Granskog Citation2003; Roper Citation2016). By running outdoors in public space, and asserting their right to do so, women can actively produce, define and (re)claim this space, not only for themselves, but also for other women runners and exercisers (see also Roper Citation2016), and for women more generally.

Feminist phenomenology provides a distinctive theoretical ‘take’ on the myriad ways in which subjective, embodied experiences are situated within historical and social structures. Offering a powerful theoretical framework for investigating women’s sporting embodiment, it generates analytic insights deeply grounded in women’s own experience of their sporting bodies, which also hold socio-cultural, and physical-cultural significance, meanings, purposes and interests. Combined with the analytic power of feminist theorisation, including the analysis of difference, phenomenology encourages a (re)examination of the structures of women’s sporting and physical-cultural experiences – pleasurable, frightening, but also quotidian and routine – whilst also acknowledging the full force of social structure in shaping these. This potent theoretical combination illuminates the lived paradoxes confronting women who seek to enjoy and challenge themselves in the outdoors and are angered at having their pleasure and enjoyment of physical activity constrained by safety concerns.

Although phenomenology firmly eschews engagement in theorisation that risks enveloping phenomena in layers of abstraction, interpretation and assumption, employing feminist phenomenology encourages some ‘theoretical generalisability’ (Smith Citation2018) of my autoethnographic findings to other women’s running. I am also acutely aware, however, that as a white-British, university-educated (as a late-entrant, ‘mature’ student), older-woman, able-bodied, non-elite runner, from a working-class background, my own experiences are bodily-specific. I took up running (initially for fitness) only in my late 20s and never encountered the performance pressures to which younger athletes are subjected (Ronkainen et al. Citation2021), for example. Thus, although running has always represented ‘work’, though unpaid, it has always had to be undertaken in the interstices of a demanding full-time (often 60+ hours per week) job. This means frequently running in a state of work-generated fatigue, which inevitably contours my lived experience of running. Furthermore, I enjoy certain corporeal privileges as well as confronting gendered disadvantages. Though subjected to all manner of verbal harassment and intimidation, and to a range of physical assaults, I have not endured racial or religion-based abuse or attack. Whilst I have been a ’fleshy’, full-breasted running-woman (in earlier days) and the target of lewd, sexist harassment, I have never been subjected to abuse based on skin colour or ethnic/religious clothing.

Although autoethnography and self-stories are still deemed problematic in some quarters of the social-science community, including vis-à-vis traditional evaluation criteria (see Sparkes Citation2020), autoethnographic research has proved a powerful and evocative means of conveying rich, sensory, nuanced and deeply embodied experiences of sport, exercise, and physical activity. In its more analytic forms, it provides a potent and explicit linkage with theoretical perspectives, grounding general (and sometimes abstract) theorisations in embodied experience, including gendered, and high-performance disability experience (e.g. Graham and Blackett Citation2021; Lowry et al. Citation2022). In the role of autoethnographic researcher, my aim is to portray personal lived experiences, vividly and in detail, so as to illustrate and explicate wider socio-cultural practices and processes; experiences that hopefully will resonate with others, and to which others will contribute their own lived-body specificities of experience, and of different intersectionalities. For, as resonated so strongly with my nascent feminist consciousness almost 50 years ago, the personal is indeed political – and women runners encounter politicised ‘public’ space every day; encounters generative of both pleasure and danger.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jacquelyn Allen-Collinson

Jacquelyn Allen-Collinson is Professor Emerita in Sociology and Physical Cultures in the College of Social Science at the University of Lincoln, UK, and former Director of the Health Advancement Research Team (HART). Currently pursuing her interest in combining sociology and phenomenology, her research interests include the lived experience of various sports and physical cultures, together with the sociology of the senses, weather, endurance, and identity work.

Notes

1. The term ‘synaesthesia’ is commonly used in English to refer to the production of a sense impression relating to one sense by stimulation of another sense, so that for example, someone might ‘see’ colours when listening to music. Here, I adopt the definition indicated.

References

- Alcoff, L.M. 2000. “Phenomenology, Post-Structuralism, and Feminist Theory on the Concept of Experience.” In Feminist Phenomenology, edited by L. Fisher and L. Embree, 39–56. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic.

- Allen-Collinson, J. 2008. “Running the Routes Together: Co-Running and Knowledge in Action.” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 37 (1): 38–61. doi:10.1177/0891241607303724.

- Allen-Collinson, J. 2009. “Sporting Embodiment: Sports Studies and the (Continuing) Promise of Phenomenology.” Qualitative Research in Sport & Exercise 1 (3): 279–296.

- Allen-Collinson, J. 2011a. “Feminist Phenomenology and the Woman in the Running Body.” Sport, Ethics & Philosophy 5 (3): 287–302. doi:10.1080/17511321.2011.602584.

- Allen-Collinson, J. 2011b. “Intention and Epochē in Tension: Autophenomenography, Bracketing and a Novel Approach to Researching Sporting Embodiment.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise & Health 3 (1): 48–62.

- Allen-Collinson, J. 2013. “Autoethnography as the Engagement of Self/other, Self/culture, Self/politics, Selves/futures.” In Handbook of Autoethnography, edited by S. Holman Jones, T. E. Adams, and C. Ellis, 281–299. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

- Allen-Collinson, J., and P. Jackman. 2022. “Earth(l)y Pleasures and Air-Borne Bodies: Elemental Haptics in Women’s Cross-Country Running.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 57 (4): 634–651 doi:10.1177/10126902211021936.

- Allen-Collinson, J., G. Jennings, A. Vaittinen, and H. Owton. 2019. “Weather-Wise? Sporting Embodiment, Weather Work and Weather Learning in Running and Triathlon.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 54 (7): 777–792. doi:10.1177/1012690218761985.

- Allen-Collinson, J., and H. Owton. 2015. “Intense Embodiment: Senses of Heat in Women’s Running and Boxing.” Body & Society 21 (2): 245–268. doi:10.1177/1357034X14538849.

- Atkinson, M. 2010. “Fell Running in Post‐sport Territories.” Qualitative Research in Sport & Exercise 2 (2): 109–132.

- Berry, K. A., K. C. Kowalski, L. J. Ferguson, and T. L. F. McHugh. 2010. “An Empirical Phenomenology of Young Adult Women Exercisers’ Body Self‐compassion.” Qualitative Research in Sport & Exercise 2 (3): 293–312.

- Blomley, N. 2009. “Public Space.” In The Dictionary of Human Geography, edited by D. Gregory, R. Johnston, G. Pratt, M. Watts, and S. Whatmore, 600–601. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Bluhm, K., and S. Ravn. 2021. ”It Has to Hurt’: A Phenomenological Analysis of Elite Runners’ Experiences in Handling Non-Injuring Running-Related Pain.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise & Health Ahead-of-print. 10.1080/2159676X.2021.1901136.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2019. “Reflecting on Reflexive Thematic Analysis.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise & Health 11 (4): 589–597. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806.

- Brice, J., M. Clark, and H. Thorpe. 2021. “Feminist Collaborative Becomings: An Entangled Process of Knowing Through Fitness Objects.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise & Health 13 (5): 763–780. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2020.1820560.

- Brockschmidt, E., and R. Wadey. 2021. ”Runners’ Experiences of Street Harassment in London.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise & Health. Ahead-of-print. 10.1080/2159676X.2021.1943502.

- Burns, M. 2003. “Interviewing: Embodied Communication.” Feminism & Psychology 13 (2): 229–236.

- Butler, J. 2006. “Sexual Difference as a Question of Ethics: Alterities of the Flesh in Irigaray and Merleau-Ponty.” In Feminist Interpretations of Maurice Merleau-Ponty, edited by D. Olkowski and G. Weiss, 107–125. University Park, PA: Penn State University Press.

- Chisholm, D. 2008. “Climbing Like a Girl: An Exemplary Adventure in Feminist Phenomenology.” Hypatia 23 (1): 9–40. doi:10.1111/j.1527-2001.2008.tb01164.x.

- Clark, A. 2018. “Exploring Women’s Embodied Experiences of ‘The Gaze’ in a Mix-Gendered UK Gym.” Societies 8 (1): 2. doi:10.3390/soc8010002.

- Cook S., Shaw J. and Simpson P. (2016). ”Jography: Exploring Meanings, Experiences and Spatialities of Recreational Road-running.” Mobilities, 11(5), 744–769. 10.1080/17450101.2015.1034455

- de Beauvoir, S. 2010-1949. The Second Sex. translated by C. Borde and S. Malovany-Chevallier. London: Vintage Books. Originally Published as Le Deuxième Sexe.

- Del Busso, L. A., and P. Reavey. 2013. “Moving Beyond the Surface: A Post structuralism Phenomenology of Young Women’s Embodied Experiences in Everyday Life.” Psychology & Sexuality 4 (1): 46–61.

- Esmonde, K. 2019. “Training, Tracking, and Traversing: Digital Materiality and the Production of Bodies And/in Space in Runners’ Fitness Tracking Practices.” Leisure Studies 38 (6): 804–817. doi:10.1080/02614367.2019.1661506.

- Fielding, H. A. 2000. “’The Sum of What She is Saying’: Bringing Essentials Back to the Body.” In Resistance, Flight, Creation: Feminist Enactments of French Philosophy, edited by D. Olkowski, 124–137. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Finlay, L. 2003. “The Intertwining of Body, Self and World: A Phenomenological Study of Living with Recently Diagnosed Multiple Sclerosis.” Journal of Phenomenological Psychology 34 (6): 157–178.

- Finlay, L. 2009. “Debating Phenomenological Research Methods.” Phenomenology & Practice 3 (1): 6–25. doi:10.29173/pandpr19818.

- Gardner, C.B. 1995. Passing by: Gender and Public Harassment. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Gimlin, D. 2010. “Uncivil Attention and the Public Runner.” Sociology of Sport Journal 27 (3): 269–284. doi:10.1123/ssj.27.3.268.

- Giorgi, A. P. 1997. “The Theory, Practice and Evaluation of the Phenomenological Method as a Qualitative Research Procedure.” Journal of Phenomenological Psychology 28 (2): 235–260.

- Graham, L. C., and A. D. Blackett. 2021. ”‘Coach, or Female Coach? and Does It Matter?’: An Autoethnography of Playing the Gendered Game Over a Twenty-Year Elite Swim Coaching Career” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise & Health: 1–16. Ahead-of-print. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2021.1969998

- Granskog, J. 2003. “Just ‘Tri’ and ‘Du’ It: The Variable Impact of Female Involvement in the Triathlon/duathlon Sport Culture.” In Athletic Intruders. Ethnographic Research on Women, Culture, and Exercise, edited by A. Bolin and J. Granskog, 27–52. New York: State University of New York Press.

- Hall, M. A. 1996. Feminism and Sporting Bodies: Essays on Theory and Practice. Champaign, Il: Human Kinetics.

- Hanold, M. 2010. “Beyond the Marathon: (De)Construction of Female Ultrarunning Bodies.” Sociology of Sport Journal 27 (2): 160–177. doi:10.1123/ssj.27.2.160.

- Hockey, J., and J. Allen-Collinson. 2007. “Grasping the Phenomenology of Sporting Bodies.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 42 (2): 115–131. doi:10.1177/1012690207084747.

- Husserl, E. 2002. Ideas: General Introduction to Pure Phenomenology. London: Routledge.

- Jackman, P. C., R. M. Hawkins, A. E. Whitehead, and N. E. Brick. 2021. ”Integrating Models of Self-Regulation and Optimal Experiences: A Qualitative Study into Flow and Clutch States in Recreational Distance Running”. Psychology of Sport & Exercise 57(102051). Ahead-of-print. doi:10.1016/j.psychsport.2021.102051.

- Jorgensen, L., G. Ellis, and E. Ruddell. 2013. “Fear Perceptions in Public Parks: Interactions of Environmental Concealment, the Presence of People Recreating, and Gender.” Environment and Behavior 45 (7): 803–820. doi:10.1177/0013916512446334.

- Koskela, H. 1999. “Gendered Exclusions: Women’s Fear of Violence and Changing Relations to Space.” Geografiska Annaler 81 (2): 111–124.

- Kruks, S. 2006. “Merleau-Ponty and the Problem of Difference in Feminism.” In Feminist Interpretations of Maurice Merleau-Ponty, edited by D. Olkowski and G. Weiss, 25–48. University Park: Penn State University Press.

- Lamont, M. 2020. “Embodiment in Active Sport Tourism: An Autophenomenography of the Tour de France Alpine ‘Cols’.” Sociology of Sport Journal 38 (3): 264–275.

- Lefebvre, H. 1977. “Reflections on the Politics of Space.” In Radical Geography: Alternative Viewpoints on Contemporary Social Issues, edited by R. Peet, 39–352. London: Methuen.

- Lev, A. 2019. “Becoming a Long-Distance Runner – Deriving Pleasure and Contentment in Times of Pain and Bodily Distress.” Leisure Studies 38 (6): 790–803. doi:10.1080/02614367.2019.1640776.

- Lev, A. 2021. “Distance Runners in a Dys-Appearance State – Reconceptualizing the Perception of Pain and Suffering in Times of Bodily Distress.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise & Health 13 (3): 473–487. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2020.1734647.

- Liimakka, S. 2011. “I Am My Body: Objectification, Empowering Embodiment, and Physical Activity in Women’s Studies Students.” Sociology of Sport Journal 28 (4): 441–460.

- Liu, L. 2021. ”Paddling with Maxine Sheets-Johnstone: Exploring the Moving Body in Sport.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport. Ahead-of-print. 10.1177/10126902211000958.

- Lowry, A., R. C. Townsend, K. Petrie, and L. Johnston. 2022. ”Cripping’ Care in Disability Sport: An Autoethnographic Study of a Highly Impaired High-Performance Athlete” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise & Health: 1–13. Ahead-of-print. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2022.2037695

- Markula, P. 2003. “The Technologies of the Self: Feminism, Foucault and Sport.” Sociology of Sport Journal 20 (2): 87–107.

- McGannon, K. R., R. J. Schenke, Y. Ge, and A. T. Blodgett. 2019. “Negotiating Gender and Sexuality: A Qualitative Study of Elite Women Boxer Intersecting Identities and Sport Psychology Implications.” Journal of Applied Sport Psychology 31 (2): 168–186.

- McNarry, G., J. Allen-Collinson, and A. B. Evans. 2019. “Reflexivity and Bracketing in Sociological Phenomenological Research: Researching the Competitive Swimming Lifeworld.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise & Health 11 (1): 38–51. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2018.1506498.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. 1964. “Eye and Mind.” In The Primacy of Perception, edited by J. M. Edie, 159–190. Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. 1968. The Visible and the Invisible, translated by A. Lingis, edited by C. Lefort. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. 2001. Phenomenology of Perception, translated by C. Smith. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Nash, M. 2017. “Gender on the Ropes: An Autoethnographic Account of Boxing in Tasmania, Australia.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 52 (6): 734–750. doi:10.1177/1012690215615198.

- Nettleton, S. 2015. “Fell Runners and Walking Walls: Towards a Sociology of Living Landscapes and Aesthetic Atmospheres as an Alternative to a Lakeland Picturesque.” The British Journal of Sociology 66 (4): 759–778. doi:10.1111/1468-4446.12146.

- Olkowski, D. 2006. “Only Nature is Mother to the Child.” In Feminist Interpretations of Maurice Merleau-Ponty, edited by D. Olkowski and G. Weiss, 49–70. State College: Penn State University Press.

- Olkowski, D., and G. Weiss, eds. 2006. Feminist Interpretations of Maurice Merleau-Ponty. State College: Penn State University Press.

- Powis, B. 2019. “Soundscape Elicitation and Visually Impaired Cricket: Using Auditory Methodology in Sport and Physical Activity Research.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise & Health 11 (1): 35–45. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2018.1424648.

- Rail, G. 1992. “Physical Contact and Women’s Basketball: A Phenomenological Construction and Contextualisation.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 27 (1): 1–25.

- Ravensbergen, L. 2020. “‘I Wouldn’t Take the Risk of the Attention, You Know? Just a Lone Girl Biking’: Examining the Gendered and Classed Embodied Experiences of Cycling.” Social & Cultural Geography 23 (5): 678–696.

- Ronkainen, N., J. Allen-Collinson, K. Aggerholm, and T. Ryba. 2021. “Superwomen? Young Sporting Women, Temporality, and Learning Not to Be Perfect.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 56 (8): 1137–1153.

- Ronkainen, N., A. Shuman, and L. Xu. 2018. “’You Challenge Yourself and You’Re Not Afraid of Anything!’ Women’s Narratives of Running in Shanghai.” Sociology of Sport Journal 35 (3): 268–276.

- Roper, E. A. 2016. “Concerns for Personal Safety Among Female Recreational Runners.” Women in Sport & Physical Activity Journal 24 (2): 91–98. doi:10.1123/wspaj.2015-0013.

- Samudra, J. K. 2008. “Memory in Our Body: Thick Participation and the Translation of Kinaesthetic Experience.” American Ethnologist 35 (4): 665–681.

- Smith, G. 1997. “Incivil Attention and Everyday Intolerance: Vicissitudes of Exercising in Public Places.” Perspectives on Social Problems 9: 59–79.

- Smith, B. 2018. “Generalizability in Qualitative Research: Misunderstandings, Opportunities and Recommendations for the Sport and Exercise Sciences.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise & Health 10 (1): 137–149. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2017.1393221.

- Smith, B, and K. R. McGannon. 2018. “Developing Rigor in Qualitative Research: Problems and Opportunities Within Sport and Exercise Psychology.” International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology 11 (1): 101–121. doi:10.1080/1750984X.2017.1317357.

- Sparkes, A. C. 2009. ““Ethnography and the Senses: Challenges and Possibilities.” Qualitative Research in Sport & Exercise 1 (1): 21–35. doi:10.1080/19398440802567923.

- Sparkes, A. C. 2020. ““Autoethnography: Accept, Revise, Reject? an Evaluative Self Reflects.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise & Health 12 (2): 289–302. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2020.1732453.

- Springgay, S., and S. E. Truman. 2022. “Critical Walking Methodologies and Oblique Agitations of Place.” Qualitative Inquiry 28 (2): 171–176. doi:10.1177/10778004211042355.

- Thomas, S., C. Smucker, and P. Droppleman. 1998. “It Hurts Most Around the Heart: A Phenomenological Exploration of Women’s Anger.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 28 (2): 311–322. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.1998.00785.x.

- Tulle, E. 2022. ”Rising to the Gender Challenge in Scotland: Women’s Embodiment of the Disposition to Be Mountaineers.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport. Ahead-of-print. 10.1177/10126902221078748.

- Turley, E. L., S. Monro, and N. King. 2016. “Doing It Differently: Engaging Interview Participants with Imaginative Variation.” Indo-Pacific Journal of Phenomenology 16 (1–2): 153–162. doi:10.1080/20797222.2016.1145873.

- Valentine, G. 1989. “The Geography of Women’s Fear.” Area 21: 385–390.

- Vera-Gray, F., and L. Kelly. 2020. “Contested Gendered Space: Public Sexual Harassment and Women’s Safety Work.” International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice 44 (4): 265–275. doi:10.1080/01924036.2020.1732435.

- Weiss, G. 2000. “Splitting the Subject: The Interval Between Immanence and Transcendence.” In Resistance, Flight, Creation: Feminist Enactments of French Philosophy, edited by D. Olkowski, 79–96. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Wesely, J. K., and E. Gaarder. 2004. “The Gendered ‘Nature’ of the Urban Outdoors: Women Negotiating Fear of Violence.” Gender & Society 18 (5): 645–663.

- Woodward, K. 2006. Boxing, Masculinity and Identity: The ‘I’ of the Tiger. London: Routledge.

- Young, I. M. 1980. “Throwing Like a Girl: A Phenomenology of Feminine Body Comportment, Motility and Spatiality.” Human Studies 3 (1): 137–156.

- Young, I. M. 1992. “Breasted Experience: The Look and the Feeling.” In The Body in Medical Thought and Practice, edited by D. Leder, 215–230. Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Young, I. M. 1998. “Throwing Like a Girl’: Twenty Years Later.” In Body and Flesh: A Philosophical Reader, edited by D. Welton, 286–290. Oxford: Blackwell.