ABSTRACT

Discerning the perspectives and working practices of those who deliver and receive a health service makes for a sensible step towards improving it. The Liverpool Co-PARS project was a four-year iterative process in which a physical activity referral scheme for inactive patients with health conditions was developed, refined, and evaluated. The aim of the present study was to explore multidisciplinary stakeholder perspectives of those involved in the co-production of Co-PARS and inform recommendations for future co-production research. We invited 5 stakeholders (service user, exercise referral practitioner, fitness centre manager, general practitioner/public health commissioner, and an academic) to co-author the present paper and provide their reflections of co-production. Four non-academic stakeholders completed a ~ 30-minute phone discussion of their personal reflections of the co-production process, transcribed in real-time by the first author and edited and checked for accuracy by the stakeholder. The fifth, academic author completed their reflections in writing. The multi-stakeholder reflections presented in this paper highlight identified strengths (multidisciplinary perspectives that were listened to and acted upon, co-production that permeated throughout the research project, real-time intervention adaptation) and challenges (homogeneous sample of service users, power imbalances, and a modestly adapted intervention) of co-production. We propose that co-production could be seen as a pro-active tool for the development of health service interventions, by mitigating potential issues encountered during latter implementation phases. We conclude with five key recommendations to facilitate future co-production research.

Background

There are increasing calls to involve non-academic experts (particularly those with lived experience of a condition or service) to co-produce health research (CIHR Citation2014; van der Graaf, Cheetham, and Redgate et al. Citation2021; Redman et al. Citation2021; Hoddinott et al. Citation2018). Despite this, service users and those with lived experience of a health condition are often excluded from research activities. In this paper we draw from multiple perspectives to reflect on a recent co-production project, importantly including voices from service users and frontline practitioners. This example is based on an innovative co-production project that aimed to develop and evaluate a physical activity referral intervention for individuals with health conditions. Below, we first provide context to this research area before summarising the co-production process followed by the aims of the current paper.

Community-based physical activity referral schemes (PARSs), traditionally termed exercise or general practitioner (GP) referral schemes, are widespread interventions that aim to increase physical activity levels among clinical populations. In the UK, such schemes typically involve primary care referral (often via a GP or Practice Nurse) to a 12-24-week intervention of prescribed exercise and subsidised access to fitness centre facilities. These PARSs are typically reserved for those who are inactive and have chronic health conditions or risk factors, that may be alleviated by increasing physical activity levels and exercise training. First introduced in the 1990s, UK PARSs proliferated, unfortunately, without adequate evidence of effectiveness or a consistent intervention framework. Subsequent UK policy has attempted to resolve this through a National Quality Assurance Framework (Department of Health Citation2001) and National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines (NICE Citation2014).

One persistent challenge has been a lack of multi-stakeholder involvement in the development and evaluation of PARSs internationally. Discerning perspectives and working practices of those who refer, deliver, and receive an intervention makes for a sensible means of improving a service (Parks et al. Citation1981). Between 2016 and 2019, a PARS for clinical populations was co-produced (termed Co-PARS hereafter) (Buckley et al. Citation2018), feasibility tested and adapted (Buckley, Thijssen, and Murphy et al. Citation2019), then pragmatically evaluated (Buckley, Thijssen, and Murphy et al. Citation2020). This development process involved iterative intervention evolution with service users (i.e. those with lived experience), exercise professionals, centre managers, general practitioners (GPs), and public health commissioners. This process transcends two of three ‘types’ of co-production as described by Smith et al. including: Equitable and experientially-informed research (i.e. input from those with lived-experience is essential and prioritises addressing marginalised groups, which includes Participatory Action Research) and Integrated Knowledge Translation (collaborating with knowledge users to enhance research impact) (Smith, Williams, and Bone et al. Citation2022). Further information regarding the types of co-production can be unpacked in Smith et al’.s paper, which forms the opening to this special issue on co-production.

Reflective practice is a core principle within healthcare, allowing individual behaviour, events, and services to be reflected upon for the purpose of future development and improvement (Macaulay and Winyard Citation2012). Critical reflection, in either written or spoken form, provides a means of consolidating learning from a situation, by asking questions such as what went well and what challenges were encountered, why things turned out as they did, and what can be learned for future practice (Koshy et al. Citation2017). In the present paper, we present reflective narratives of the co-production process within Co-PARS from different stakeholder perspectives (service user, service providers, commissioner and academic), highlighting strengths, challenges, and potential solutions to help inform future co-production of health services.

Context and co-production process

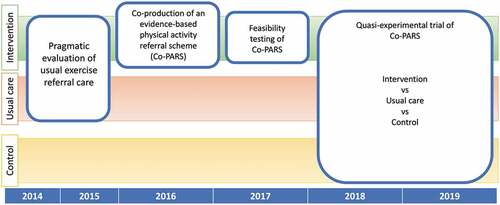

Prior to the Co-PARS project, service evaluations of usual exercise referral care in Liverpool showed a high drop-out in the first few weeks of the scheme and a lack of formal progress support, with 58% of participants reporting formal contact with exercise instructors at induction only (unpublished data). Our aim with the Co-PARS project was to work with local stakeholders to develop an intervention that addressed these shortcomings by drawing on scientific evidence (including behaviour change theory), practical ‘craft’ knowledge, and service user expertise. Subsequently, the Liverpool Co-PARS project became a three-year (2016–2019) process of iterative co-production, refinement, and evaluation of a novel, locally tailored exercise programme. provides an overview of this iterative process, which included a needs analysis, co-production, feasibility testing and adaptation, and finally a three-arm pragmatic quasi-experimental trial evaluating the effectiveness of Co-PARS.

Figure 1. Liverpool Co-PARS Project encompassing a needs analysis (pragmatic evaluation of usual care) in 2014–2015, co-production of a Co-PARS in 2016–2017, feasibility testing and adaptation of Co-PARS in 2017, and finally, a pragmatic quasi-experimental trial evaluating the effectiveness of Co-PARS compared to usual care and a no-treatment control. Full details of the methods underpinning each project phase can be found in the corresponding publications (Buckley et al. Citation2018, Citation2019, Citation2020).

Materials and methods

For the present study, we provide reflective narratives of the co-production phase of a four-year iterative Co-PARS project through five different stakeholder perspectives. Stakeholders were purposely selected to include representation from multiple roles (e.g. service user, service provider, service commissioner) and were invited to take part based on their active role within the Co-PARS project (either during the co-production phase or the feasibility and trial phases) i.e. a criterion purposeful sampling strategy was used. The five stakeholders included in this study were the senior academic and exercise psychologist for the Co-PARS project (Dr Paula Watson), an exercise referral service user (Jacqueline Newton), an exercise referral practitioner (Stacey Smith), a fitness centre area manager (Brian Noonan), and a GP and public health commissioner (Maurice Smith).

Four of the five stakeholders (PW, JN, SM, MS) were members of the original (2016) co-production group (which consisted of public health commissioners (n=4), fitness centre area manager (n=1), GP/public health commissioner (n=1), exercise referral practitioners (n=2), health trainer (n=1), health trainer coordinator (n=1), service users (n=5), plus academic experts in exercise referral (n = 1), exercise psychology (n = 1,) and exercise physiology (n=1)). The fifth member (BN) became involved after the programme had been co-produced but prior to feasibility testing.

In attempt to standardise the context of discussions, all stakeholders were asked 4 key questions:

What was your involvement in the co-production of the adapted exercise referral scheme in Wavertree Aquatics Centre?

The idea of the co-production process was that commissioners, managers, practitioners, academics, and service users would work together to come up with a scheme that suits everyone. What did you feel were the strengths of this process and what areas were challenging?

What do you think we could learn from this project to take forward for future health improvement projects?

How did you feel being a part of this co-production project impacted on your personal and/or professional development?

To gain stakeholder perspectives (and in an attempt to provide equitable engagement for those not used to writing reflectively for academic journals), the lead author [BJRB] offered a phone call with the four non-academic stakeholders to discuss their experiences of the Co-PARS project and complete the initial write-up on their behalf. All four of the non-academic stakeholders requested the phone call instead of drafting their own perspectives in writing. Phone call discussions lasted between 20–40 minutes and were completed in March-April 2021. During the discussions, the lead author made notes in real-time, clarifying verbally to check for accuracy. Directly following each stakeholder discussion, the lead author summarised the notes to form a meaningful prose. This draft was then sent to the respective stakeholder to check the content was an authentic representation of their viewpoint and amend as appropriate before approving for inclusion in the paper. As co-authors, all stakeholders reviewed, edited, and approved the final version of the manuscript and gave permission to be named and for their narratives to be printed verbatim. For the academic stakeholder (PW), their perspectives and reflections were drafted in writing and sent to the lead author to be included in the manuscript.

This methodology is aligned with relativist epistemology (i.e. reality is varied and multiple, which is a critical concept to appreciate in any co-production research). The qualitative methods and processes drew on reflective practice (Knowles, Gilbourne, and Cropley et al. Citation2014) and ‘reflexive confessions’ (Darpatova-Hruzewicz Citation2022) in an effort to share multiple perspectives from a range of stakeholders embedded in a co-production process. Where critical self-reflection can be used to drive improved professional practice (Dugdill, Coffey, and Coufopoulos et al. Citation2009), reflexivity moves beyond reflection, involving critical exploration of what we know and do not know in attempt to understand our position in relation to others (Edge Citation2011; Rogers, Papathomas, and Kinnafick Citation2021). Drawing on the narrative results and recognising that the notation of discussions and writing is a form of analysis (Richardson and St Pierre Citation2008), the lead author [BJRB] acts as the storyteller through the reflexive narratives of multiple stakeholders (Smith and Sparkes Citation2020), and communicates this via a confessional tale in the present paper. According to Sparkes (Citation2002) (Sparkes Citation2002), a confessional tale draws on ‘personal experience with the explicit intention of exploring methodological and ethical issues as encountered in the research process’ (p. 59). Finally, the analysis and interpretation of results were driven by the primary aim of identifying important strengths and challenges of a co-production process. We therefore conclude with five recommendations believed to be important in facilitating co-production research and to alleviate challenges identified in this manuscript. In the section that follows, we present each perspective in turn, structured by the four questions above.

Results

Service user perspective (Jacqueline)

What was your involvement in the co-production of the adapted exercise referral scheme in Wavertree Aquatics Centre?

I went along because I was approached by the exercise referral staff to see if I would support the meetings by giving my experiences of using the referral scheme. I had been through the referral scheme and used the leisure centre services for several years at the time. I have experience of using different lifestyle-related services in Liverpool and really liked the GP referral scheme; I had really promising experiences of the referral scheme at Wavertree including improved health markers and I even lost some weight. I also had a good social life through the referral scheme. I was therefore keen to help the referral staff and others if possible.

I attended the initial development group meetings where a few of us [service users] gave our thoughts/experiences about using the referral scheme. Following the development meetings, I was also invited to help with recording behaviour change training videos for the delivery staff of the referral scheme.

The idea of the co-production process was that commissioners, managers, practitioners, academics and service users would work together to come up with a scheme that suits everyone. What did you feel were the strengths of this process and what areas were challenging?

The development meetings were good because we had all the different views in one room. The commissioners, managers, and ‘number crunchers’ who probably didn’t know what it was like to deliver the scheme, on the shop floor, were able to listen to the staff and us who had experience of the service first-hand … I think this was really impressive. The fact that we [service users] were invited to give our opinion and we were listened to was really powerful.

To be honest, we didn’t really think anything was wrong with the scheme – you know the saying ‘if it’s not broken, don’t fix it … ’ I‘m aware that others may have fallen through the cracks and didn’t get what I got out of the scheme. We [service users in the group] had formed a tight social group during the referral scheme. I really don’t know if others built social groups like we did – and this would have a very different impact on their experience. For me, it was the friendships that we made that was key.

What do you think we could learn from this project to take forward for future health improvement projects?

For me, I think the most important thing is to listen to the people that actually use the service and those on the ground who deliver the service – see what they want, see if they actually want the change. Make sure they are included and feel listened to, as we did.

How did you feel being a part of this co-production project impacted on your personal and/or professional development?

I don’t think it affected me personally/professionally, however, I was honoured to be asked to be involved in this project where we were involved in something that included people at the very top all the way down to us. It was great that I was simply asked, and the fact that I felt I was listened to was again, powerful.

Exercise referral practitioner perspective (Stacey)

What was your involvement in the co-production of the adapted exercise referral scheme in Wavertree Aquatics Centre?

I attended the development meetings in 2016 and helped coordinate and deliver the intervention from 2018–2019. During the development meetings, I helped provide the information about what was practical and can work in the centre. From there, my role was to try and manage the staff to deliver the adapted intervention – whilst giving feedback to the academic team.

The idea of the co-production process was that commissioners, managers, practitioners, academics and service users would work together to come up with a scheme that suits everyone. What did you feel were the strengths of this process and what areas were challenging?

This allowed us to get a variety of information. For example, I was able to provide operational information, like the realistic delivery perspectives, the service users helped us understand what they needed, the commissioners funding, and the academics for the science.

It was interesting to learn that GPs have their own struggles. We used to get annoyed at the level of detail provided in the patient referral forms, but later learned they have only 10 minutes to complete this (on top of all the other clinical stuff that is likely more urgent). We therefore can’t be expecting a lot of baseline information to be provided at the GP level.

I didn’t realise how much it would take to organise the referral scheme. As it was delivered in the leisure centre where I already worked, I thought we could just change a few things and then we would be done. It was a big learning curve as we discussed how to organise the funding, adapt operations to provide a much more holistic intervention, whilst collaborating with the clinical commissioning group to provide something that goes beyond the gym.

One key challenge included different views on who could attend the referral scheme and who was responsible for these patients. GPs thought anyone should be able to walk in, however, we, as exercise practitioners didn’t think this was appropriate. I also think having the patient book their own induction is too daunting [which would be the case for self-referral] - I have seen clients standing outside not knowing whether to go and book one or how to do it. This isn’t an issue if they are referred by a healthcare professional and an induction is booked for them.

In some of the development meetings with stakeholders, I didn’t understand a lot of the funding issues that were being discussed. The way the public health funding is all separated is difficult. Some of our initial ideas in the development meetings were not possible because of politics and funding. It was too difficult to get initiatives that had similar goals to work together for the same/or similar outcomes.

The academics got carried away with the number of measures (i.e. questionnaires) that they wanted patients to complete during consultations. We [exercise referral practitioners] felt they were very similar and repetitive. At first, the data collection was really labour intensive. We had to tell the academic team there were too many things to do at the first consultation – I don’t feel the academic team appreciated how time consuming it was in practice. After adapting these processes and testing it, we managed to agree on a more streamlined approach with only the most important information for the research included.

We also went through similar motions with the delivery of the intervention. At first, we thought all the staff would need a GP referral qualification, which was difficult because not all staff want to do this. We then realised that the more staff we involved, the more difficult it became to organise the intervention and collect data for the studies (a lot of data were missing in the first testing phases). Therefore, we had to rearrange some of the work rotas to have a set of core practitioners run the intervention. This worked much more effectively.

What do you think we could learn from this project to take forward for future health improvement projects?

With the correct funding and procedures in place, it can be done. I think you need other organisations to help create multidisciplinary processes that work together to provide better options for patients. Also, you need to think about the bigger picture, in our case, it wasn’t just increasing exercise, it was about developing a community group that can support themselves socially.

How did you feel being a part of this co-production project impacted on your personal and/or professional development?

It’s not just about the gym and exercise. It’s also about mental wellbeing and social support. It has helped me realise I’m more of a life coach these days (than an exercise practitioner), and I need to understand a person in order to help them. Before this project I had a limited appreciation for health/PA behaviour change and the needs of those we cater for. I have a much better appreciation for the multiple initiatives that could/should be working together towards a single goal – improved health and wellbeing.

Finally, as an instructor, the training and development from the academic teams (and behaviour change skills training from Paula) was really beneficial and has changed my long-term practice as a practitioner.

Fitness centre area manager perspective (Brian)

What was your involvement in the co-production of the adapted exercise referral scheme in Wavertree Aquatics Centre?

I joined the team in November 2016, just after the initial development meetings had been completed and before the testing phases. As a centre manager, I have previous experience of ER delivery operations.

From my perspective, my involvement in this project mainly consisted in facilitating the delivery staff on the ground; helping the academic and delivery staff to overcome pragmatic problems. This included managing staff capacity and tweaking the delivery of the intervention and/or the way staff worked to allow the intervention to be delivered in practice, at the fitness centre. Practically, this involved regular meetings with the academic team and the exercise delivery staff.

The idea of the co-production process was that commissioners, managers, practitioners, academics and service users would work together to come up with a scheme that suits everyone. What did you feel were the strengths of this process and what areas were challenging?

Obvious strengths were getting the perspectives from everyone involved. For me, the key stakeholders were the service users, and getting their feedback direct to the practitioners was invaluable – allowing us to adapt and make changes to the intervention. We were making the changes that were driven by real-world problems, not problems we just came up with. This helped us implement improvements to facilitate intervention adherence and behaviour change, which is not something we had previously focussed on. It’s a better model from a business and individual health perspective.

As always, the key challenge is the funding. Having the funding available to do what’s best for those that need support. Trying to deliver an intervention with limited funding, to provide the necessary options and intensity patients need, was an ongoing challenge. The sustainability is also really important. As with many of the user groups, it is the long-term affordability that can determine long-term engagement. As the scheme is heavily subsidised, it’s trying to develop opportunities for long-term access. As we amended the membership packages over the 3–4 years we worked on this development project, we came up with packages that we believed were affordable and met certain population needs, e.g. those that had dependents to look after and could only attend during certain hours. We later found that clients did seem to be transitioning well from the ERS to the longer-term membership – but more is needed to be done here. Many felt the 12-16-weeks was too short before going it alone.

What do you think we could learn from this project to take forward for future health improvement projects?

Giving the stakeholders authentic buy-in is critical. Also, making it [the health intervention] enjoyable is important. Any intervention where you need to change behaviour needs to be attractive.

A big thing for me is that it’s not just about numbers and physical outcomes. We need to better develop social circles that provide friendship and social support etc. This has important health benefits and seems to be a key need for those who enrol on exercise referral schemes.

How did you feel being a part of this co-production project impacted on your personal and/or professional development?

It was something I was very interested in personally and professionally. It was interesting to see how the academics viewed exercise referral and to learn more about some of the evidence behind exercise and PA behaviour change.

Specifically, I have come to realise there are many benefits beyond centre attendance, that are important. I think the work highlighted (to me at least) the importance of these facilities for the clients, it’s a central community hub that can facilitate physical, social and mental benefits … not just numbers on a spreadsheet.

Finally, it raised the importance of involving multiple stakeholders from day one and making sure they are working towards the same goal. I believe that’s what made this project successful, within funding constraints.

Public health commissioner and GP perspective (Maurice)

What was your involvement in the co-production of the adapted exercise referral scheme in Wavertree Aquatics Centre?

I got involved to provide clinical input as the ‘Living Well’ (Prevention) Clinical Director of the Liverpool Clinical Commissioning Group, and as a GP with a particular interest in PA. Pragmatically, I also had my own experience as a GP of referring patients to exercise referral schemes.

As part of the co-production process, I was invited to a sort of ‘working group’ where I attended a series of meetings (where the intervention was developed), but also several additional one-to-one discussions with the research team. These one-to-one discussions were to iron out specific details and discuss pragmatics as the project developed.

The idea of the co-production process was that commissioners, managers, practitioners, academics and service users would work together to come up with a scheme that suits everyone. What did you feel were the strengths of this process and what areas were challenging?

I thought it was a good process, which was collaborative and included many different points of view from clinical and commissioning perspectives to those representing the delivery of the scheme. We also had the LJMU team, providing the academic input and evidence, which I wouldn’t have otherwise known about. This process was therefore key to represent different perspectives.

The feedback sessions were particularly helpful, where you [academic team] summarised the findings of the prior meetings and checked we agreed – it was clear you were listening.

In terms of challenges, I guess I had a very particular point of view; that the referral should be very easy for GPs to refer, or even make it so that GPs were not necessary to refer. However, the council seemed more averse to this, potentially representative of different cultures and the more risk averse view of those who wear a council hat. This issue of risk aversion versus innovation played out quite regularly, from my perspective.

It’s my view that we are often constrained by preconceived rules, which are simply constructs, rather than immutable laws (i.e. GP refers patient, patient goes to referral, etc). We need to ask more ‘Do we really have to stick to X rules?’

What do you think we could learn from this project to take forward for future health improvement projects?

We need to ask more what the construct is – can we challenge the current rules that are in place for the system. If not, fine let’s adapt – if we can challenge the status quo, let’s innovate!

So, at the very beginning, we need to make clear everyone understands ‘what there is now’ and ‘this is what control or power we have’ before we go trying to adapt or create anything.

How did you feel being a part of this co-production project impacted on your personal and/or professional development?

I certainly enjoyed the process and it felt like I was doing something useful that was part of my work portfolio at the time. I genuinely felt the group would benefit from a GP (my) perspective, not an expert, but a GP. I also think it’s interesting being exposed to these different worlds … academia, service delivery, and commissioning, all with very different experience and perspectives.

Academic perspective (Paula)

What was your involvement in the co-production of the adapted exercise referral scheme in Wavertree Aquatics Centre?

I was the academic lead for the Co-PARS project, responsible for its conception, design and chairing the multidisciplinary academic steering group. I was also the exercise psychology/behaviour change lead and PhD supervisor for the first author, who was the day-to-day driver for the project.

Ever since I did my MSc placement with an exercise referral scheme (back in 2003) I had dreamed of doing a project like this. As an exercise psychologist, I have always felt exercise referral schemes are a ‘missed opportunity’ to support the behaviour change of some of our most at-risk populations. I had been doing some evaluation work with the local exercise referral scheme and when the chance arose to apply for PhD studentship funding in 2015, my colleagues and I designed a project I hoped could make a genuine difference to exercise referral practice. Fortunately, we were successful and Co-PARS was born.

The idea of the co-production process was that commissioners, managers, practitioners, academics and service users would work together to come up with a scheme that suits everyone. What did you feel were the strengths of this process and what areas were challenging?

For me, the main strengths of the co-production process were the fact it brought people together who wouldn’t otherwise have been having those conversations. Whilst it is well recognised there are benefits in collaborative working, too often nowadays people are under so much stress with their day jobs they get little time or headspace to come away and ask ‘how can we work together in this, and is there a better way we could do this?’ The co-production meetings enabled participants to voice their concerns and ideas within a psychologically safe space, practitioners to be in a room with commissioners they rarely have contact with, and collaborative group decisions to be made that reflected everyone’s needs.

One thing we did have to think carefully about was how to balance ‘power’ within an inherently unbalanced group. We achieved this in part through subgroup discussions to ensure everyone was given a voice before feeding back to the broader group. There were however times when we made mistakes, such as when a provider and commissioner were in the same sub-group and the issue of funding came up. We also gave careful consideration to group facilitation, and the decision to have an independent facilitator allowed myself and others to offer our own expertise when appropriate. But I did stop myself on a couple of occasions and wonder ‘to what extent are we really co-producing’? We (Liverpool John Moores University) were driving the project, we had a lot of voices in the room, we were passionate about what we were doing and at the end of the day it was us that took the data back to the office to decide the next steps. So, were we really achieving the sense of shared ownership we were aiming for? On reflection I began to wonder if perhaps ‘shared ownership’ is an idealism rather than a reality, as someone needs to lead to make things happen.

Another challenge relates to the broader scale impact of this type of work. We based our phased approach on the Medical Research Council framework for developing complex interventions, and the next logical step would have been to apply for funding to conduct a full randomised controlled trial (RCT). This posed us some difficulties however, because it was not clear what we were looking to ‘test’. If it were the co-produced scheme itself, this made little sense because the whole foundation of the intervention was the co-production process, therefore we couldn’t expect an intervention co-produced to fit one geographical locality to be lifted and successfully delivered elsewhere. Perhaps a more meaningful approach would be to do a controlled trial of the co-production process itself, but we haven’t yet found the confidence to run that one past the paradigm purists.

What do you think we could learn from this project to take forward for future health improvement projects?

In recent years I think we are seeing growing recognition of the importance of research having an impact on practice, and with it the need to move beyond traditional positivist approaches. For me, the Co-PARS project highlighted the importance of working with those on the ground who will be delivering and receiving services, and how evidence-based approaches can be embedded in practice within a relatively short timescale (when compared with the commonly estimated 17 years for research to reach practice) (Morris, Wooding, and Grant Citation2011).

To move forward in this respect, I would like to see the notion of ‘implementation science’, and related funding opportunities, broadened beyond the traditional linear research model. I was once shot down at a conference when I talked passionately about Co-PARS as an example of implementation work, to which a leading international figure politely explained to me that ‘I wasn’t doing implementation science: implementation science is when you have first proven the intervention’s efficacy then you scale it up’. Yet, what we did in the Co-PARS project was all about implementation. A key strength of the iterative, phased development approach was that it allowed the intervention to be embedded in practice during the research process itself. We were able to tackle teething problems as and when they arose, and we developed a culture of mutual learning and respect – if something wasn’t working, we had an open conversation and worked out a better way to do things. Unlike more traditional researcher-led interventions, delivery was not dependent on the research team. When the research ended, the co-produced intervention continued to operate.

Similarly, something that continues to disappoint me is the low priority given to this type of work by peer-reviewed journals in the Sport and Exercise Medicine field. With the first co-production study, there seemed to be a mismatch between the frequent interest and positive feedback Ben received when he presented the work at conferences (three prizes within one year) and our attempts to publish in esteemed scientific journals (constant knockbacks and signposting to open-access sister journals). If we can view implementation science as a more dynamic, iterative two-way cycle between evidence and practice, we might have a better chance of creating more efficient, sustainable solutions.

I think we can also broaden how we view the idea of ‘co-production’. In Co-PARS, we labelled phase 1 the ‘co-production phase’ as this is when we conducted the formal, multi-stakeholder workshops to co-produce an intervention framework. But in reality, the co-production permeated far beyond this into the second and third phases of the project. Had we abandoned the idea of co-production before the intervention was piloted and trialled, I’m confident the project would not have had the impact it did. Instead, we continued to work in mutual partnership with the providers to iteratively co-develop the intervention in response to the evidence we were collecting and to the delivery challenges arising. My role became one of facilitator, providing a structure around which the practitioner team could come up with logistical solutions to enhance delivery. I learned that sometimes the support needed from others isn’t academic expertise, but a facilitator to bring out the craft expertise in others.

My final point to take forward is that to ensure equity within the co-production process it is important we don’t treat everyone the same. There may be people in the group who are not used to email communication, who cannot attend workshops during working hours, or who do not have wifi access at home. Therefore, it is important to work with stakeholders in a way that supports them to share their voices. For example, after our co-production workshops we sent out an online survey to gather stakeholders’ views of the process. We could simply have e-mailed this to everyone and said ‘everyone has had an equal chance to respond therefore we are being fair’. However, this would have disadvantaged the service users within the group, many of whom did not routinely use email or may not have had internet access. Therefore, Ben arranged to meet with the service users in person to gather their views on the process, thus providing an equitable opportunity to contribute.

How did you feel being a part of this co-production project impacted on your personal and/or professional development?

The Co-PARS project further strengthened my belief that research and practice need to go hand in hand, and stakeholder involvement lies at the heart of successful intervention design. It was through my late mentor Professor Lindsey Dugdill that I learned the value of working with, and listening to the voices of those who will be delivering and benefiting from the intervention (Dugdill, Stratton, and Watson Citation2009). I’ve since realised that Lindsey and I had been doing ‘co-production’ for years (Dugdill, Stratton, and Watson Citation2009; Watson, Dugdill, and Murphy et al. Citation2013), it just wasn’t called as such. We called it participatory, bottom-up, joined-up, collaborative, iterative, formative or alternative methodologies.

Being involved in this co-production process has reinforced my view that the difference we make to practice is far more important than the impact factor of the journal we publish in. My respect for the ‘craft knowledge’ of the practitioners and managers I’ve been working with is second to none, and I have a growing appreciation of the multi-level constraints public sector staff are under. This is something I take forward to other projects and when working with academics who aren’t used to this – I encourage people to take a step back, consider our vision for how the intervention will be delivered in practice, and take projects slower in order to make a lasting difference.

Discussion

Although the co-production and evaluation of the Co-PARS project is well documented (Buckley et al. Citation2018, , Citation2019, Citation2020), stakeholder perspectives of a co-production process have not been previously explored in depth or qualitatively. The present paper therefore highlights multi-stakeholder reflections of the Co-PARS project. Below, we discuss key topics highlighted by different stakeholders involved in the co-production process, some of the challenges encountered, and potential solutions to help guide others undertaking co-production research. A summary of the key topics are encapsulated within , which presents five recommendations to support future co-production research.

Table 1. Five recommendations for co-production research.

Norström and friends underline that co-production should be context based, pluralistic, goal oriented, and interactive ((Norström, Cvitanovic, and Löf et al. Citation2020)). One of the key challenges of co-production is the management of power imbalances and ensuring everyone has a voice (i.e. pluralistic). In this respect, it is particularly promising that a service user, exerciser referral practitioner, fitness centre area manager, and GP/public health commissioner all felt that they were listened to, and their views valued and acted upon. This is aligned with a brief quantitative survey used as an evaluation tool, collected following the co-production workshops, whereby all respondents felt they had been given the opportunity to share their views and 89% felt their views had been acted upon ‘very much’ (with 11% answering ‘somewhat’) (Buckley et al. Citation2018). Not only was this promising from a research perspective, but also from a business perspective, as discussed by Brian when reflecting on the enhanced outcomes that can be achieved through listening to the needs of service users.

As Paula notes, in order to adequately engage all stakeholders and ensure equity of representation, it was important that different stakeholders were not treated the same (as demonstrated in the present paper in the data collection of academics and non-academics). In the Co-PARS project, this mainly involved meeting with service users face-to-face and helping them complete questionnaires or discussing topics in person, rather than through email communication and electronic surveys, as is often the norm in academia. We also learnt to vary who was involved in each small group activity (e.g. sometimes mixed job roles, sometimes grouped by job role), depending on the task, which can enable more challenging conversations to play out (e.g. funding and capacity). Through a co-production process, nephrologists, health economists, members of civil society (seeking equity in access to dialysis), and responsive policy makers saved ~50,000 patients with end stage renal disease, by co-producing equitable dialysis policy (Chuengsaman and Kasemsup Citation2017). Inequity has also been investigated in a secondary analysis of the UK National Referral Database, whereby creative best practices for widening access (e.g. partnership building), maintaining engagement (e.g. workforce diversity), and tailoring support have been identified for patients with health conditions and low physical activity levels (Oliver et al. Citation2021).

Paula’s point about co-production permeating beyond the formal ‘co-production phase’ was also highlighted by Brian and Stacey who considered the importance of the ongoing two-way communication with the academic team whilst the intervention was being delivered. This is eloquently presented in international co-production work underpinned by the concept: the ‘triangle that moves the mountain’; whereby researchers, service users, and policy makers worked together to achieve change (Tangcharoensathien, Sirilak, and Sritara et al. Citation2021). One example of Norström’s fourth co-production principle (i.e. the necessity for frequent interaction and engagement) (Norström, Cvitanovic, and Löf et al. Citation2020) includes the 6-years (2010–2016) of stakeholder engagement between Thai representatives from multiple government agencies, such as health, social welfare, education, and civil society organisations who developed and implemented legislation to reduce adolescent pregnancy (Ministry of Public Health Citation2016). This provides a powerful example of the ongoing communication (and action) between academics and those delivering/receiving a service that can facilitate real-world implementation success. It also highlights the need to appreciate the substantial commitment (e.g., time and resources) for co-production to be meaningful, and not just a ‘tick box’ exercise to meet academic funding or ‘impact’ pressures. For example, our Co-PARS research took four years to implement in one site, and the implementation of the Thai Prevention and Solution of the Adolescent Pregnancy Problem Act, as mentioned above, took six years (Ministry of Public Health Citation2016).

We have also learned that when embedding research and interventions into practice there is often the need to fit within existing infrastructures and how co-production is essential to facilitate this. According to the first (context based) principle emphasised by Norström et al. co-production should be considered within social, economic and ecological contexts in which they are embedded, and the confines and opportunities of the surrounding circumstances (Norström, Cvitanovic, and Löf et al. Citation2020). The Co-PARS academic team in particular initiated this project with the plan to develop a novel and innovative comprehensive lifestyle intervention. However, it quickly became apparent that if we were to make any feasible changes, these would need to fit within existing healthcare structures and resources. This resulted in implementing relatively small adaptations from an outside perspective (e.g. patient reported outcome measures, behaviour change support consultations, longer follow-up etc.), but as Stacey highlighted, to successfully implement these ’small adaptations’ took several years and a substantial amount of work. As Maurice reflected, it was helpful to ask ourselves ‘can we challenge the current rules that are in place for the system. If not, fine let’s adapt – if we can challenge the status quo, let’s innovate!’

Although co-production is not straightforward and may require additional resources and time than traditional research to conduct (Oliver, Kothari, and Mays Citation2019), we argue that this additional work may in fact facilitate implementation in the latter phases of research, with the potential to reduce the well documented time lag between health service research and change in practice (Morris, Wooding, and Grant Citation2011). From an academic perspective, this co-production process has instilled an appreciation of the multi-level constraints public sector staff are under. Similarly, Stacey (exercise referral practitioner) highlighted her new-found appreciation of the complexity involved in co-producing and evaluating a health service. Thus, through co-production both academic and non-academic stakeholders developed a newfound appreciation for the other stakeholder’s circumstances and unique challenges. A revelation that would not be possible by organisations and stakeholders working in silos.

Maurice’s concerns about ‘risk aversion versus innovation’ raised a pertinent point within the field of healthcare. On the one hand, the GP perspective (Maurice) was that it should be as easy as possible with minimal screening and paperwork. Whereas service managers had litigation concerns of potentially ‘high-risk’ patients being referred to an exercise-based intervention without GP ‘sign-off’. Highlighted in a paper titled ‘The dark side of co-production’ (Oliver, Kothari, and Mays Citation2019), Oliver and colleagues debate the tensions that can arise during co-produced research processes between different interests involved. However, they also argue that these tensions are how inherent power imbalances and conflicts in co-production research are expressed. Such discussions, at least from our academic perspective, were seen as a central strength of co-production. Discussion of such contrasting opinions and pragmatic challenges allowed for potential future issues affecting the intervention to be ‘played out’ early and inform the intervention, rather than disrupting progress later in the research process. Co-production could therefore be seen as a pro-active strategy towards intervention development, by facilitating the mitigation of potential issues in latter implementation phases.

It must be acknowledged that the service users who were invited to participate in the co-production process were unlikely to be representative of the wider exercise referral demographic. Specifically, Jacqueline notes that the service users we had recruited for the co-production phase had completed the exercise referral scheme and did not seem to highlight any major need for change. These service user representatives could therefore be described as ‘completers’ or ‘adherers’ (as they all completed/adhered to the exercise-based rehabilitation programme). They had also developed a strong friendship group within the referral scheme. This was likely due to the recruitment method of service users, which was undertaken by the exercise referral practitioners who pragmatically were only going to invite users who they had a good working relationship with. Nonetheless, the service users were one of multiple groups contributing to Co-PARS, and each group had something different and valuable to contribute. The need for change was in fact academically driven, with drop-out rates, re-referrals, lack of behaviour change support only visible at a strategic level (not necessarily at a service user level). However, in determining how we went about change and how we addressed these challenges, service users, managers, commissioners, and practitioners were all integral.

Methodological considerations

In the present paper, the data collected were not pseudonymised, which may have influenced the statements of individual stakeholders. However, due to the psychologically safe environment (that gave value to all voices and encouraged constructive debate), we would expect concerns about social desirability to be lower than might have been the case had stakeholders been unfamiliar with the authors.

Although discussion of relevant literature in this article was based on merit, several of the high-quality co-production examples were based in Thailand. However, because we are discussing the method (i.e. co-production) and not a specific intervention or service, we do not believe this creates any issues of transferability, given co-production can facilitate the development of context-specific interventions that are appropriate for local needs.

Finally, we faced some challenges in publishing our co-production research as its own entity (rather than as a component within a randomised controlled trial, for example). It is however promising to see Nature publish a piece providing examples of how co-production can be integrated at every step of the research process (Hickey, Richards, and Sheehy Citation2018), and a published collection of co-production research highlighting its role in strengthening health systems recently published in the BMJ (Redman et al. Citation2021), and not to forget this welcomed special issue on co-production in sport, exercise, and health sciences in QRSEH.

Conclusions and recommendations for future co-production research

The multi-stakeholder reflections presented in this paper highlight some of the strengths and challenges of co-production from the perspectives of the Co-PARS project. Key strengths included multidisciplinary perspectives that were listened to and the perception they were acted upon, co-production that permeated through the full project, which also facilitated real-time adaptations to overcome unforeseen difficulties. Co-production could therefore be seen as a preventive tool for the development of health service interventions, by helping to identify and mitigate potential issues that may arise during latter implementation phases. Some of the challenges reflected upon included a sample of service users who likely did not represent the diverse nature of the referral scheme population (particularly those most at risk), power imbalances during co-production workshops, and implementing relatively modest intervention adaptations (although the latter might also be seen as a strength). Based on the Co-PARS work, provides five recommendations to facilitate future co-production research within multidisciplinary teams.

Disclosure statement

BJRB has received research funding from Bristol Myers Squibb/Pfizer.

References

- Attwood, S., E. van Sluijs, and S. Sutton. 2016. “Exploring Equity in Primary-Care-Based Physical Activity Interventions Using PROGRESS-Plus: A Systematic Review and Evidence Synthesis.” The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 13 (1): 60. doi:10.1186/s12966-016-0384-8.

- Buckley, BJR., DHJ. Thijssen, RC. Murphy, L E F. Graves, G. Whyte, F B. Gillison, D. Crone, P M. Wilson, and P M. Watson. 2018. ”Making a Move in Exercise Referral: Co-Development of a Physical Activity Referral Scheme.” Journal of Public Health (Oxf) 40 (4): e586–93. published Online First: 2018/04/25. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdy072.

- Buckley, BJ., DH. Thijssen, RC. Murphy, Graves LE, Cochrane M, Gillison F, Crone D, Wilson PM, Whyte G, Watson PM. 2020. ”Pragmatic Evaluation of a Coproduced Physical Activity Referral Scheme: A UK Quasi-Experimental Study.” BMJ Open 1010:e034580. published Online First: 2020/10/03. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034580

- Buckley, BJR., DHJ. Thijssen, RC. Murphy, Graves LE, Whyte G, Gillison F, Crone D, Wilson PM, Hindley D, Watson PM. 2019. ”Preliminary Effects and Acceptability of a Co-Produced Physical Activity Referral Intervention.” Health Education Journal 78 (8): 869–884. doi:10.1177/0017896919853322.

- Chuengsaman, P., and V. Kasemsup. 2017. ”PD First Policy: Thailand’s Response to the Challenge of Meeting the Needs of Patients with End-Stage Renal Disease.” Seminars in Nephrology 37 (3): 287–295. published Online First: 2017/05/24. doi:10.1016/j.semnephrol.2017.02.008.

- CIHR, 2014. Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research - Patient Engagement Framework. Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Accessed 29 November 2022. https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/48413.html

- Darpatova-Hruzewicz, D. 2022. “Reflexive Confessions of a Female Sport Psychologist: From REBT to Existential Counselling with a Transnational Footballer.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 14 (2): 306–325. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2021.1885481.

- Department of Health. 2001. Exercise Referral Systems: A National Quality Assurance Framework. London: Department of Health.

- Design Council, 2005. “Framework for Innovation: Design Council's evolved Double Diamond.” Design Council. Accessed 29 November 2022. https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/our-work/skills-learning/tools-frameworks/framework-for-innovation-design-councils-evolved-double-diamond/.

- Design Council. 2015. Design Methods for Developing Services. London. Accessed 29 November 2022 https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/fileadmin/uploads/dc/Documents/DesignCouncil_Design%2520methods%2520for%2520developing%2520services.pdf.

- Dugdill, L., M. Coffey, A. Coufopoulos, Byrne K, Porcellato L. 2009. ”Developing New Community Health Roles: Can Reflective Learning Drive Professional Practice?” Reflective practice 10 (1): 121–130. doi:10.1080/14623940802652979.

- Dugdill, L., GS. Stratton, and PM. Watson. 2009. “Developing the evidence base for physical activity interventions.” Physical Activity and Health Promotion: Evidence-Based Approaches to Practice. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. 60–81.

- Edge, J. 2011. The Reflexive Teacher Educator in TESOL: Roots and Wings. New York: Routledge.

- Hickey, G., T. Richards, and J. Sheehy. 2018. ”Co-Production from Proposal to Paper.” Nature 562 (7725): 29–31. published Online First: 2018/10/05. doi:10.1038/d41586-018-06861-9.

- Hoddinott, P., A. Pollock, A. O’Cathain, I. Boyer, J. Taylor, C. MacDonald, S. Oliver, and J L. Donovan. 2018. ”How to Incorporate Patient and Public Perspectives into the Design and Conduct of Research.” F1000Research 7: 752. published Online First: 2018/10/27. doi:10.12688/f1000research.15162.1.

- Knowles, Z., D. Gilbourne, B. Cropley, Dugdill L. 2014. Reflective Practice in the Sport and Exercise Sciences: Contemporary Issues. London: Routledge.

- Koshy, K., C. Limb, B. Gundogan, K. Whitehurst, and D J. Jafree. 2017. ”Reflective Practice in Health Care and How to Reflect Effectively.” International Journal of Surgical Oncology (n Y) 2 (6): e20. published Online First: 2017/11/28. doi:10.1097/ij9.0000000000000020.

- Macaulay, CP., and PJW. Winyard. 2012. “Reflection: Tick Box Exercise or Learning for All?” BMJ 345: e7468. doi:10.1136/bmj.e7468.

- Ministry of Public Health, United Nations Population Fund, Asian Forum of Parliamentarians on Population and Development, Et Al. The Prevention and Solution of the Adolescent Pregnancy Problem Act, BE. 2559, 2016.

- Morris, Z., S. Wooding, and J. Grant. 2011. ”The Answer is 17 Years, What is the Question: Understanding Time Lags in Translational Research.” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 104 (12): 510–520. PMID - 22179294. doi:10.1258/jrsm.2011.110180.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2014. NICE Public Health Guidance 54. Exercise Referral Schemes to Promote Physical Activity. London: NICE. Accessed 29 November 2022. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph54.

- Norström, AV., C. Cvitanovic, MF. Löf, West S, Wyborn C, Balvanera P, Bednarek AT, Bennett EM, Biggs R, de Bremond A, Campbell BM. 2020. ”Principles for Knowledge Co-Production in Sustainability Research.” Nature Sustainability 3 (3): 182–190. doi:10.1038/s41893-019-0448-2.

- Oliver, EJ., C. Dodd-Reynolds, A. Kasim, and D. Vallis. 2021. ”Inequalities and Inclusion in Exercise Referral Schemes: A Mixed-Method Multi-Scheme Analysis.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18 (6): 3033. published Online First: 2021/04/04. doi:10.3390/ijerph18063033.

- Oliver, K., A. Kothari, and N. Mays. 2019. ”The Dark Side of Coproduction: Do the Costs Outweigh the Benefits for Health Research?” Health Research Policy and Systems 17 (1): 33. PMID - 30922339. doi:10.1186/s12961-019-0432-3.

- Parks, RB., PC. Baker, L. Kiser, R. Oakerson, E. Ostrom, V. Ostrom, S L. Percy, M B. Vandivort, G P. Whitaker, and R. Wilson. 1981. “Consumers as Coproducers of Public Services: Some Economic and Institutional Considerations.” Policy Studies Journal 9 (7): 1001–1011. doi:10.1111/j.1541-0072.1981.tb01208.x.

- Redman, S., T. Greenhalgh, L. Adedokun, S. Staniszewska, and S. Denegri. 2021. “Co-Production of Knowledge: The Future.” BMJ 372 (n434). doi:10.1136/bmj.n434.

- Richardson, L., and E. St Pierre. 2008. “A Method of Inquiry.” Collecting and Interpreting Qualitative Materials 3 (4): 473.

- Rogers, E., A. Papathomas, and F-E. Kinnafick. 2021. “Preparing for a Physical Activity Intervention in a Secure Psychiatric Hospital: Reflexive Insights on Entering the Field.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 13 (2): 235–249. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2019.1685587.

- Skivington, K., L. Matthews, SA. Simpson, P. Craig, J. Baird, J M. Blazeby, K A. Boyd. 2021. ”A New Framework for Developing and Evaluating Complex Interventions: Update of Medical Research Council Guidance.” BMJ 374 (n2061): n2061. doi:10.1136/bmj.n2061.

- Smith, B., and AC. Sparkes. 2020. Qualitative Research. Tenenbaum, Gershon, Eklund, Robert C. Handbook of Sport Psychology. 4: 999–1019. London: Wiley.

- Smith, B., O. Williams, L. Bone, Collective TM. 2022. ”Co-Production: A Resource to Guide Co-Producing Research in the Sport, Exercise, and Health Sciences.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 1–29. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2022.2052946.

- Sparkes, A. 2002. Telling Tales in Sport and Physical Activity: A Qualitative Journey. London: Human Kinetics.

- Tangcharoensathien, V., S. Sirilak, P. Sritara, Patcharanarumol W, Lekagul A, Isaranuwatchai W, Wittayapipopsakul W, Chandrasiri O. 2021. ”Co-Production of Evidence for Policies in Thailand: From Concept to Action.” BMJ 372: m4669. doi:10.1136/bmj.m4669.

- van der Graaf, P., M. Cheetham, S. Redgate, Humble C, Adamson A. 2021. ”Co-Production in Local Government: Process, Codification and Capacity Building of New Knowledge in Collective Reflection Spaces. Workshops Findings from a UK Mixed Methods Study.” Health Research Policy and Systems 19 (1): 12. doi:10.1186/s12961-021-00677-2.

- Watson, P., L. Dugdill, R. Murphy, Knowles Z, Cable NT. 2013. ”Moving Forward in Childhood Obesity Treatment: A Call for Translational Research.” Health Education Journal 72 (2): 230–239. doi:10.1177/0017896912438313.