ABSTRACT

How does trade liberalisation shape post-Soviet Limited Access Orders (LAOs) where dominant elites restrict access to political and economic resources for the sake of private gains? By drawing on the case of trade liberalisation between the EU and Ukraine, this paper argues that in post-Soviet LAOs the effect of trade liberalisation largely depends on the quality of the pre-existing alliance between political and economic elites in exporting sectors. The findings imply that external trading partners wishing to promote economic and political opening must not ignore the ownership structure of key exporting sectors and the involvement of these key owners in rent-seeking practices. Otherwise, trade liberalisation helps to ensure the durability of LAOs.

1. Introduction

It is conventional wisdom that post-Soviet countries suffer from rent-seeking elites. The latter exploit their privileged access to political and economic resources to control the state and the economy for the sake of private gains, albeit to different extent (Balmaceda Citation2013; Hale Citation2014; Ademmer, Langbein, and Börzel Citation2019). Following North, Wallis, and Weingast (Citation2009) dominant coalitions of networked politicians/entrepreneurs lead such Limited Access Orders (LAOs) (for a conceptualisation of the term, cf. the introduction to this special issue). These dominant coalitions do hardly change with elections. Their ability to manipulate elections and to restrict political access is closely linked to their ability to extract rents thanks to their control over economic resources, such as trade and capital, and vice versa. Their power and capacity to restrict access to both political and economic resources may hence be the main factor ensuring the durability of LAOs.

A driver for regime change from LAO to Open Access Order (OAO) that has thus far received less scholarly attention concerns the effect of trade liberalisation on overcoming the institutional status in LAOs (for a discussion of other factors likely to affect regime change, cf. the introduction to this special issue). This paper therefore asks whether trade liberalisation, i.e. the lifting of bilateral tariff and non-tariff barriers to trade, contributes to greater economic and political competition in such a context.

The answer to this question is highly contested in the literature. While some have argued that trade liberalisation can increase political and economic competition even in non-democratic countries (Frye and Mansfield Citation2003; North, Wallis, and Weingast Citation2009; Levitsky and Way Citation2010; Connolly Citation2013), others found the opposite effect. The latter group has argued that rent-seeking elites rather use market opening to preserve the institutional status quo (Hirschman Citation1968; Hellman Citation1998; Adserà and Boix Citation2002).

This paper contributes to the debate by investigating how trade liberalisation between the European Union (EU) and Ukraine since 2008 has affected economic and political opening in Ukraine’s LAO. We argue that trade liberalisation helps to consolidate the power position of rent-seeking elites who restrict access to economic and political resources, if external trading partners - in that case the EU - ignore (or accept) the political economy of LAOs (for a discussion about the unintended consequences of promoting economic opening, cf. the introduction to this special issue). We are certainly not the first underlining the unintended consequences of tight cooperation with the EU. The existing literature has so far dealt with negative effects of EU political conditionality and assistance in the areas of good governance, human rights protection and democracy. Researchers identified state capacity and domestic incentives for state capture as key intervening variables in that respect (see, for example, Börzel and Pamuk Citation2012; Shyrokykh Citation2017; Richter and Wunsch Citation2020). With our focus on the effects of EU trade liberalisation on economic and political opening, we add a new aspect to this debate.

In our study we draw on the argument made by Doner and Schneider (Citation2016) who have shown that the quality of the pre-existing alliance between the state and economic actors determines how countries use economic opportunities for development that emerge, among others, from trade liberalisation: Should rent-seeking economic elites with direct links to the political elites be present in the main export sectorsFootnote1, it is likely, we argue, that trade liberalisation will help consolidating rather than overcoming the pre-existing status quo of limited access to economic and political resources. We focus on examining the effect of trade liberalisation on exports only because Ukraine and other post-Soviet LAOs are poorly integrated in global value chains. Thus, their key export sectors do hardly depend on imported inputs (Hoekman, Jensen, and Tarr Citation2014; Smits et al. Citation2019).

To sustain our arguments, the paper proceeds as follows. The next section will review the existing literature on LAOs and derive two hypotheses on how trade liberalisation affects political and economic opening in LAOs. We will also justify the case selection and discuss the operationalisation of our variables. Section three investigates the explanatory power of our two hypotheses based on an in-depth analysis of the effects of trade liberalisation on political and economic opening in Ukraine. The conclusion summarises our findings and discusses the implications for EU governance of market integration in the post-Soviet space.

2. Trade liberalisation and opening in LAOs: theory and measurement

The question of whether trade liberalisation increases political competition in non-democracies has received lots of scholarly attention. The answer to this question is yet contested within the literature. In the tradition of Seymour Lipset (Citation1959), one group of scholars argues that trade liberalisation and political competition are positively correlated. The assumed underlying mechanism is that trade liberalisation contributes to economic diversification, i.e. it helps to broaden the number of actors benefitting from access to economic resources like trade. In so doing, it helps to bring about an emerging middle class seeking stronger political participation and accountability of state authorities. Along similar lines, Frye and Mansfield (Citation2003) showed that in non-democracies, where power within governments is fragmented, new elites with weak ties to the old regime are well placed to use trade liberalisation as a weapon against their political opponents, thereby increasing political competition. Thus, market opening triggers the rise of a multiplicity of economic actors across whom the benefits of liberalisation are dissipated and to an extent where access to economic organisations becomes broad and impersonal (North, Wallis, and Weingast Citation2009, 40). In a similar vein, Levitsky and Way (Citation2010, 25) argued that liberalisation is likely to promote political change, since increased economic exchange multiplies the number of actors with personal, professional, and most importantly economic ties to a democratic partner. Further, Connolly (Citation2013) showed that trade liberalisation causes changes in the structure of exports, as a result of which the role and power of economic actors alter to an extent that economic actors with access to economic resources become more diverse. This in turn results in increased competition at the political level.

By contrast, another group of scholars has argued that greater trade openness helps to consolidate the institutional status quo of restricted access to political and economic resources (Hirschman Citation1968; Hellman Citation1998; Adserà and Boix Citation2002). This is especially the case, if rent-seeking domestic actors predominantly benefit from trade liberalisation. The latter might try to reap rentsFootnote2 from their privileged access to trade: They are likely to (further) weaken democratic institutions to exclude potential competitors and maintain the institutional status quo. Put differently, powerful domestic economic actors can use the (new) wealth reaped from more open markets and capitalise on the pre-existing weaknesses of the state to capture it. They use state capture to control institution-building and the making of economic policies (Amable and Palombarini Citation2009; Doner and Schneider Citation2016).

Both research strands point to an important scope condition for trade liberalisation to have a positive effect on political and economic opening. That is presence or absence of rent-seeking domestic actors. Along these lines, Doner and Schneider (Citation2016) specified that the quality of the pre-existing alliance between state and business actors prior to trade liberalisation affects whether and how economic opportunities arising from market access are used for development. Drawing upon this argument we assume that trade liberalisation is more likely to induce opening, if a) sectors with a diversified ownership structure have turned into major exporting sectors or b) should greater export opportunities have encouraged new players to enter key exporting sectors, thus increasing internal competition. This is because a more diversified ownership structure of key exporting sectors will result in a growing number of actors with access to economic resources, thereby reducing the piece of cake for everybody. As a consequence, it is less likely that a powerful economic elite will emerge or consolidate its pre-existing power position and manipulate political decisions for the sake of private gains.

Against this background, our first hypothesis reads:

H1) The more trade liberalisation increases the number of economic actors who benefit from greater export opportunities, the more liberalised trade helps to overcome limited access to economic and political resources in LAOs.

Correspondingly, we assume that trade liberalisation undermines economic and political opening if a) prior to trade liberalisation rent-seeking elites held assets in sectors that later on benefit most from open markets, b) prior to (or shortly after) trade liberalisation rent-seeking elites shift their assets to or increase their stakes in sectors that (they expect to) benefit most from trade liberalisation, and/or c) new rent-seeking elites are on the rise since the sectors they had their assets in prior to liberalisation benefit from the process and gain significance. Thus, our second hypothesis reads:

H2) The more trade liberalisation induces growing exports in sectors dominated by rent-seeking elites, the more liberalised trade helps conserve the status quo of restricted access to economic and political resources in LAOs.

To test our two hypotheses, we focus on trade liberalisation in the context of Ukraine’s accession to the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in 2008 and the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (DCFTA) with the EU, which entered into force in 2014, up until the end of President Petro Poroshenko’s term in office in April 2019. Both, market opening in the context of the WTO and the EU, lend themselves as most likely cases for a positive causal relationship between trade liberalisation and opening in LAOs. As for the WTO, that is the case because the latter combines trade liberalisation with demands for at least selective regulatory integration. As Manger and Pickup (Citation2016) argued, domestic rent-seekers face more difficulties to maintain the institutional status quo as WTO members, since it becomes increasingly difficult to arbitrarily erect trade barriers or to hide protectionist measure due to WTO regulations. The power to seek economic rents is either reduced or protectionism becomes more transparent, triggering demands from those who could benefit from a different economic policy. As for the DCFTA with the EU, it is based on even more encompassing regulatory integration with transnational market rules than the WTO charter and other trade agreements. Unlike the WTO, the DCFTA also entails at least some assistance for creating and/or strengthening domestic developmental capacities to support market integration (Bruszt and Langbein Citation2017). Thus, we should expect economic and political opening to proceed faster in Ukraine after the conclusion of the DCFTA in 2014. In turn, if increasing trade liberalisation in the context of the WTO and/or with the EU is not inducing political and economic opening in Ukraine’s LAO, we can hardly expect to observe a positive causal relationship in the context of other free trade arrangements that entail fewer demands for regulatory integration and fewer assistance. These include the Comprehensive and Free Trade Agreement (CEPA) with Armenia or the (Enhanced) Partnership and Cooperation Agreements with other post-Soviet countries.

We chose the case of Ukraine, because – just as the other two DCFTA countries Georgia and Moldova – the country classifies as a LAO that is relatively balanced in its restrictions of political and economic access but is still comparatively open (Ademmer, Langbein, and Börzel Citation2019). In Ukraine, elite-led resistance to opening is therefore present to roughly similar or lower degrees than in other post-Soviet LAOs (Ademmer, Langbein, and Börzel Citation2019). At the same time, Ukraine receives more EU assistance for using the economic opportunities offered by trade liberalisation compared to Moldova and Georgia (Wolczuk and Zeruolis Citation2018, 16–17), let alone other post-Soviet LAOs that are embedded in less encompassing trade agreements with the EU. We therefore assume that if trade liberalisation with the EU does not induce the opening of Ukraine’s LAO, we will most likely observe similar outcomes in all other post-Soviet LAOs that are embedded in equally or less encompassing trade arrangements with the EU.

To assess whether trade liberalisation undermines or furthers economic and political competition, we take a closer look at the ownership structures and market shares of the five most successful export sectorsFootnote3 when it comes to trade with the EU prior and after trade liberalisation. We assume that in order for trade liberalisation to contribute to the transition from a LAO to an OAO, economic competition has to evolve in the key exporting sectors. If big holdings owned by so-called oligarchs, who are defined as economic actors with links to the dominant political elite, dominate the exporting sectors even after trade liberalisation, it indicates that economic and political competition remains restricted. Trade liberalisation thus contributes to the consolidation of the LAO. If we observe that small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) or companies without political affiliations to the ruling rent-seeking elite have been able to increase their market share after trade liberalisation, we take this as an indicator for increasing economic and political competition.

In terms of operationalisation, we measure the extent to which sectors benefit from trade liberalisation on the basis of changes in their shares in total exports to the trading partner with whom trade liberalisation was negotiated. It it is well established that liberalised trade leads to an expansion of foreign trade between the trading partners (Helleiner Citation1994; IMF Citation2016). More precisely, we assess changes in Ukraine’s export shares to the EU across sectors after Ukraine’s accession to the WTO in 2008 and after the conclusion of the DCFTA in 2014. These years mark significant changes in the reduction of tariff and non-tariffs barriers between the EU and Ukraine. We look at both changes in shares of sectoral exports to the EU as a percentage of total exports to the EU as well as at changes in the total volume of sectoral exports to the EU to account for the price effect. An important caveat that remains is that we cannot attribute exactly to what extent larger exports to the EU are due to better terms of trade or result from a loss of export opportunities to the markets in Russia and other post-Soviet countries. That said, the opportunity for Ukrainian exports to re-orient towards the EU also depends on greater accessibility of the EU market.

3. Trade liberalisation and opening in Ukraine’s LAO

Asymmetrical trade liberalisation between the EU and Ukraine started as early as 1993 when Ukraine became a beneficiary of the Generalized System of Preferences. As a result, the EU massively reduced import tariffs on Ukrainian machinery and most industrial goods (Langbein Citation2015). Trade liberalisation between the EU and Ukraine took pace when Ukraine became a member of the WTO in 2008. Ever since, the two parties have gradually reduced tariffs and quotas with most positive effects in the following three sectors: agrifood (for example, via reduced tariffs for sunflower seed oil) and improved market access in terms of larger quotas and better instruments to deal with anti-dumping cases for the steel sector and the chemical industry (Movchan Citation2007; Bessonova, Merschenko, and Gridchina Citation2015).

In addition, the EU’s “autonomous trade preferences” (ATP) towards Ukraine, which entered into force on 23 April 2014, have unilaterally reduced the EU’s tariffs on Ukrainian goods in line with the EU’s DCFTA commitments.Footnote4 In sum, trade has been liberalised on most sectors ever since (only 36 agricultural products have tariff-free quotas) (cf. Annex I-A, Appendix A of the Association Agreement).Footnote5 Non-tariff barriers such as food safety standards and quotas are yet conceived of as the major impediment to food exports (Emerson et al. Citation2006).

As 2008 was also the year of the global financial and economic crisis that severely hit Ukraine’s economy, we compare pre-WTO export shares for 2007 with export shares for 2011, as this is the year Ukraine reached pre-crisis levels in terms of exports to the EU. We also compare pre- and post-DCFTA export shares, namely the years 2013 and 2017.

shows that metals, mineral products, agrifood, and machinery and electrical equipment have had the highest share in Ukraine’s exports to the EU for the past ten years. They accounted for nearly 70% of Ukraine’s exports to the EU in 2007, and for nearly 80% of exports by 2017 in the context of the DCFTA.

Table 1. Ukraine’s key sectors with the highest shares in exports to the EU, in %.

Notably, the significance of individual sectors has changed over time. Metals and minerals occupied the top two positions during the period before and after accession to the WTO. Both sectors lost significance in the following years. Agrifood is now the top exporting sector to the EU. That said, metals and mineral products still account for 37% of Ukraine’s export to the EU today.

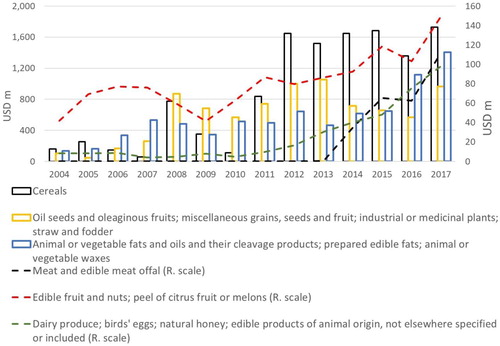

The more traditional Ukrainian exports to the EU market, such as mineral products, metals and machinery/electrical products, have been depressed since 2008. This is due to a number of factors, mainly related to low commodity prices (e.g. for iron ore and crude steel), intense competition for access to the EU market with other countries (such as China), as well as the existence of non-tariff barriers. Yet, since 2013/14 exports of electrical equipment products and other manufacturing industries picked up. Ukrainian producers increasingly turned to the EU markets in order to substitute for the lost market share on the Russian and other markets in countries belonging to the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) in the aftermath of Russia’s annexation of Crimea and the armed conflict in Eastern Ukraine. Conversely, despite non-tariff barriers in the area of food quality, some sectors of Ukraine’s agrifood industry were able to adopt its businesses to EU standards and started to supply goods to EU markets. Namely, three new sectors gained importance in Ukrainian trade balance with the EU over 2014–2018 – meat (mainly poultry), fruits and dairy products, although their export volume is still far below the volume of Ukraine’s traditional agrifood exports (cereals, oil seeds, vegetable fat) ().

Figure 1. Ukraine's exports of animal and vegetable products to the EU. Source: Eurostat Citation2019. Note that the bars correspond to the left scale, while the lines correspond to the right scale.

To understand the implications of these numbers for Ukraine’s LAO in terms of political and economic opening, we will take a closer look at changes in the ownership structures of Ukraine’s leading export sectors to the EU since 2007. In line with our two hypotheses, we investigate whether trade liberalisation has helped to strengthen the power position of big firms and holdings owned by Ukraine’s rent-seeking elites, or whether it has helped to broaden the range of economic actors benefitting from open markets, in particular SMEs.

The top five export items of Ukraine’s agrifood industry remained more or less the same: As in 2007, more than 60% of today’s agrifood exports are grain, fats and oils, as well as oil seeds. Meat and dairy together still make up less than 6% of all exports. Vegetable and fruit still constitute less than 2% of all exports (Eurostat Citation2019).

In the grain sector, the ownership structure did not change significantly since Ukraine liberalised its trade with the EU in the course of WTO accession and in the context of the DCFTA: international traders continue to dominate Ukraine’s grain sector, even more so because Ukraine has less space in using discriminatory measures against foreign grain traders due to transnational regulations imposed by the WTO and the EU (Kobuta, Sikachyna, and Zhygadlo Citation2012; Voloshin Citation2017). Nevertheless, local grain producers such as Nibulon’s Oleksiy Vadaturskiy and Kernel’s co-owners Vitaliy Khomutynnyk and Andriy Verevskiy gained importance in the course of increasing trade liberalisation. The latter incentivised local producers to invest in agricultural production and to form their own grain resources rather than merely acting as intermediaries between producers and traders (Kobuta, Sikachyna, and Zhygadlo Citation2012). Vadaturskiy, Khomtynnyk and Verevskiy used to enjoy close ties with the previous dominant elite under former Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovich. After the Euromaidan in 2014 and the coming to power of Petro Poroshenko, they had become part of the new dominant elite led by Poroshenko, and used their ties for large-scale VAT refunds and tax exemptions in exchange for political loyalty (Balabushko et al. Citation2018; Lewis Citation2018; Latifundist.com Citation2018a).

Still, the share of SMEs in agricultural exports has always been larger than in other industries. The introduction of the free-trade regime with the EU reinforced this trend. As a result, the number of duty-free quotas has been growing over recent years. Export administration procedures in agriculture got simplified (EasyBusiness Citation2018). According to official statistics (State Statistics Service Citation2019), in 2016, 60% of Ukraine’s SMEs in the agrifood sector reported that they were exporters. What is more, according to a USAID survey in 2016, 60.1% of SME respondents (all sectors) stated that they were exporting to the EUFootnote6, mainly to Poland (19%), Germany (18%), the Baltic states (12%) and the UK (10%). These numbers are indicative for the export destinations of SMEs operating in the agrifood sector (USAID survey quoted in EasyBusiness Citation2018).

In most cases, SMEs are not challenging or are not in direct competition with big agrifood holdings. Unlike large agro-holdings, many SMEs deal with niche products, such as fruits, vegetables, or organic food. This is because grain harvesting, for example, which is one of Ukraine’s major agricultural export commodities, requires certain economies of scale. A company’s competitiveness depends on its ability to accumulate significant land banksFootnote7, which is more feasible for large agro-holdings. SMEs may be part of value chains of agro-holdings or large agro-traders since the latter often purchase additional volumes of marketable grain from SMEs. In principle, SMEs could increase benefits from trade and compete with large players on Ukraine’s agrifood market by forming cooperatives that would allow them to conduct large-scale exports. So far, this has not happened.

What is the share of SMEs in the three sectors which gained importance in Ukraine’s trade balance with the EU over 2014–2018, namely meat (mainly poultry), fruits and dairy products? As shows, Ukraine’s meat industry witnessed the highest growth rates as of 2017 in terms of agrifood exports to the EU. Ukraine’s WTO accession liberalised meat trade between Ukraine and the world, including the EU, but this initially led to higher meat imports, while meat exports from Ukraine only started to accelerate in 2011 (State Statistics Service Citation2019). Poultry meat production, in particular, is reported to have pushed export shares to the EU since the 2012 decision of the EU to allow Ukrainian poultry importsFootnote8 and the subsequent endorsement of the DCFTA. Myronivsky Hliboproduct (MHP) dominates exports in the sector. The company controlled about 80% of total poultry exports to the EU in 2017, though it became a major poultry producer already in 2012 and exporter in 2013. The anticipated conclusion of the DCFTA provided MHP with sufficient incentives to align with EU food safety standards. This helped the company to eliminate one of the key non-trade barriers for poultry meat exports to the EU: In 2013, MHP received permissions to export poultry meat to the EU from the Food and Veterinary Office of the European Union (European Commission Citation2013). Furthermore, once the DCFTA was signed in 2014, MHP employed an efficient strategy to increase its exports to the EU over the levels protected by duty-free tariff-rate import quota (TRQ) set for two categories of poultry meat (European Commission Citation2015).Footnote9

SMEs have always dominated the fruit industry. Unlike in grain or poultry, the economy of scale is not as critical of a factor for fruit exports. Ukrainian fruits exporters are not confronted with strict EU food safety quality standards from the EU side, and are characterised by a more diversified structure of exports.Footnote10 This makes the sector less attractive for large agro-holdings than the grain or the poultry sector. Organic crops production (and exports) is driven mainly by small innovative companies with an average land bank of two to 15 hectares (Agrobusiness of Ukraine Citation2018). The area of organic lands in Ukraine (quite remarkably) doubled between 2008 and 2017 and saw its sharpest increase (along with exports) in 2013–2014. The EU-Ukraine DCFTA was one of the factors that allowed many of Ukraine’s organic fruit producers to obtain the European certification for organic products. The DCFTA did not only trigger the development of a legislative framework for producing and selling organic food in Ukraine. It also fostered the dialogue between the Ministry of Agrarian Policy and Food of Ukraine, the EU Commission and EU certification bodies for organic food on reasonable import regulations for Ukrainian organic products. As a result, the European Commission approved 19 Ukrainian private and internationally accredited certification bodies for organic food in 2018 (UNEP Citation2018).

Finally, a few larger foreign companies such as Danone, and Lactalis and mid-sized Ukrainian owned companies have mainly dominated the local dairy industry over the past decade (Latifundist.com Citation2013, Citation2018b; Strubenhoff Citation2017). Slow liberalisation of EU-Ukraine trade in dairy following Ukraine’s WTO accession did hardly incentivise Ukrainian dairy plants to comply with EU food safety standards.Footnote11 Ukraine’s dairy exports to the EU were thus close to zero until 2014 (Langbein Citation2015). Yet, following an abrupt contraction of dairy exports to Russia and other CIS countries after 2014 and a further decline in EU tariffs and quotas imposed on Ukrainian dairy imports in the course of the DCFTA, growing approximation of Ukrainian food quality legislation to the relevant EU acquis made the re-orientation to the EU market possible.

As a result, ten Ukrainian dairy plants passed the inspections of the European Food and Veterinary Office (FVO) and were allowed to export to the EU in January 2016. As of the end of 2018, 24 plants received these permissions (Trade Control and Export System Citation2019) and at least half of them were part of large companies that dominate the market for dairy products in Ukraine.Footnote12 The new quality standards seem to have changed the structure of the value chain in the industry and opened more space for SMEs to participate. This is because the demand for high quality raw materials for dairy products (e.g. milk) has been growing as a result of stricter EU food safety standards. While Ukrainian dairy plants that used to export to the Russian or CIS markets could buy raw milk from private households, EU standards make this option non-viable. The new food quality regulations are likely to make the large dairy companies cooperate with SMEs that are capable to maintain the required minimum quality of milk.

The previous discussion suggests that an increasing number of SMEs operating in Ukraine’s agrifood sector, above all in the dairy and organic fruits industries, have been able to reap the benefits of trade liberalisation with the EU. In line with our first hypothesis, liberalisation in agrifood trade has thus helped to diversify the range of domestic actors with access to economic resources and, hence, helped to increase economic competition in Ukraine. At the same time, and in line with our second hypothesis, our analysis also suggests that big holdings whose owners enjoy close ties to the dominant elite clearly continue to dominate agrifood exports to the EU, particularly in the grain and meat sectors. What is more, unlike SMEs, most of Ukraine’s agro-holdings are said to benefit, one way or another, from political connections, which they use to restrict access to economic resources. Many owners of agro-holdings in Ukraine use various channels to access economic rents: via preferential access to asset purchase or leasing of land, access to state aid or subsidised loans from state-owned banks, to name a few (see an extensive discussion of specific cases in Balabushko et al. Citation2018 and in Horovetska, Rudloff, and Stewart Citation2017). One anecdotal example to illustrate such rent-seeking behaviour can be found in local media reports: in 2014, the leading poultry producer and exporter Yuriy Kosyuk served as a Deputy Head of President Poroshenko’s Administration. During that time, MHP successfully managed to receive timely value-added tax (VAT) refunds unlike other companies. After this practice was abolished (under IMF pressure) and replaced by direct budget subsidies, MHP received nearly half of the UAH 4.1 billion state subsidies in 2017, which somewhat ironically, had originally been designed for business development among SMEs (Ukrpravda Citation2017). Up until today, big companies such as MHP continue to enjoy preferential access to subsidies (Kupfer Citation2018). Kosyuk, for example, was appointed Advisor to the President in 2015.

While the capture of state aid is relatively easy to detect and contest, including in international arbitration, it is far more difficult to reveal rents resulting from internal market deficiencies. Along with the misuse of state aid, agro-holdings also extract rents from the lack of land reform. They block the establishment of a properly functioning competitive land market in Ukraine. The ban on the sale of agricultural land results in limited access to land resources. Agro-holdings, which manage to control large areas of land, benefit most from trade liberalisation. This, in turn, increases their political influence on economic policy-making. By contrast, the (usually small) landowners have few alternative options to leasing their land to large agro-holdings at prices regulated by the (captured) government of Ukraine. In the absence of a proper market politically connected companies, especially those with close ties to dominant local and national elites, benefit the most by obtaining preferential and privileged access to using the land (Kovensky Citation2017). All in all, our analysis shows that increasing economic competition in Ukraine’s agrifood industry resulting from trade liberalisation with the EU has thus far been too limited to equip SMEs with sufficient bargaining power to change the rules of the games when it comes to economic policy making. In line with our second hypothesis, liberalisation of agrifood trade between the EU and Ukraine has predominantly strengthened old and new rent-seeking elites with close ties to Ukraine’s current political leadership. It has not helped to significantly diversify the range of economic actors with access to economic and, hence, political resources.

Trade liberalisation between the EU and Ukraine regarding metals and minerals displays similar results. Yet, in contrast to the agricultural sector, where we witness the rise of new oligarchs, such as Yuriy Kosiuk, elites representing Ukraine’s metals and mineral products industries have not changed over the course of the past decade. What is more, unlike in the agrifood sector where key owners shifted their loyalty to the newly elected President Poroshenko following the Euromaidan, key owners in metals and minerals maintained their ever close ties with the previous power network of the former President Viktor Yanukovych, currently presented by the Opposition Bloc in the Ukrainian parliament. In these industries, firms associated with oligarchs currently account for over 40% of turnover and over half of all assets (Balabushko et al. Citation2018). Large holdings have always dominated the sector and especially its exports since Ukraine mainly exports semi-finished products like ingots (World Bank Citation2004). Trade statistics suggest that they benefited from trade liberalisation with the EU, though to a lesser extent than dominant elites in the agrifood business (). The export of more traditional Ukrainian exports to the EU market, such as mineral products and metals decreased since 2008. Low commodity prices (e.g. for iron ore and crude steel) and intense competition for access to the EU market with other countries like China are the root causes for this trend (Stahl Centrum Citation2019)

More precisely, oligarchs in Ukraine’s metals and mineral product industries, including Rinat Akhmetov, who owns the group System Capital Management (SCM) has been dominating Ukraine’s steel industry since the mid-2000s (World Bank Citation2004). He was the richest man in Ukraine according to Forbes in 2016. As mentioned above, Akhmetov and other oligarchs dominating these industries were no longer part of Ukraine’s dominant elite under President Petro Poroshenko. Despite the fact that they were often linked with political factions in opposition to the presidential majority in the Ukrainian parliament, some groups, such as SCM, still enjoyed access to political resources even after the political changes in 2014. For example, the government under Poroshenko allowed selected companies to trade with the non-government controlled territories in eastern Ukraine for some time. What is more, SCM ended up as a major beneficiary of the government regulation on coal pricing methodology that allows the Ukrainian government to set prices for coal above market rates (see Całus et al. Citation2018).

Rather than expanding into new areas, for most of the period between 2007 and 2017, the steel and chemical conglomerates were preoccupied with expanding their core businesses or ensuring that their backbone companies stayed afloat, given the hike in imported gas prices in 2010 and in the aftermath of the 2008 global economic crisis.Footnote13 Hence, along with the change in dominant political elites (in 2010) and trade liberalisation effects, the global crisis of 2008 and local crisis of 2014 had equal, even more profound effects on the politically connected groups, as well as on Ukraine’s economy in general. Investments made by politically connected companies in these sectors into telecoms, real estate, finance, construction or agricultureFootnote14 remain marginal compared to the value of their core businesses. Thus, and in line with our second hypothesis, liberalisation of trade in metals and mineral products has hardly helped to diversify the range of domestic economic actors benefitting from open markets. Access to economic resources remains limited to a few firms owned by oligarchs who do not challenge the status quo of restricted access to political resources as this would undermine opportunities for rent-seeking.

Last but not least, machine building is one of the most diversified sectors in terms of industries and political affiliations of key businessmen: the machinery sector is well represented by both dominant and rival elites. For example, Motor Sych is owned by Vyacheslav Boguslayev who is linked with the old dominant elite close to former President Yanukovich. By contrast, automotive companies, such as Bohdan Corporation and (largely state-owned) companies in the defense industries are associated with the political network led by former President Petro Poroshenko (Patrioty.org.ua Citation2018). Ever since Ukraine became a beneficiary of the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) in 1993, the EU imposed low import tariffs on Ukrainian machinery. Nonetheless, Ukraine’s largest machinery producers have predominantly sold their products on the Russian and other post-Soviet markets as well as on the domestic market ever since. For example, even when the armed conflict in eastern Ukraine started, Russia remained Motor Sich’s main trading partner for military equipment and civic aviation (Birnbaum Citation2014). State-owned defence producers represented by the UkrOboronProm holding have both large exports (over USD 700mn in 2017) and domestic markets with growing volumes following the 2014 conflict. The EU is not the key market of such exports: China, Russia and Thailand accounted for 64% of Ukraine’s arms exports over 2014–2018 (SIPRI Citation2019). In the automotive industry, neither Bogdan nor ZAZ are strongly integrated in EU supply chains. They mainly produce for the domestic market or serve as assembly platforms for Western automotive firms. They have been unable to compete with increasing Western imports enjoying lower import tariffs in the course of Ukraine’s WTO accession and the negotiation of the DCFTA (Langbein Citation2016). While firms like Motor Sych and Ukrainian defence companies engage in rent-seeking practices as regards the manipulation of public procurement or state aid, trade liberalisation with the EU has hardly helped to consolidate their power position.

However, there are a number of EU-based and international producers of automotive parts and componentsFootnote15, especially in electrical machine building and electrical appliances, who placed their investments in Ukraine. The sector is rapidly expanding in particular since the conclusion of the DCFTA in 2014. The inflow of these green-field investors is one of the factors that not only explains why the EU became a major export market for Ukraine’s machine-building industry but also why Ukrainian SMEs in the machinery sector were able to increase their share in machinery exports to the EU over the past years (Gudz’ Citation2018). Still, their growing economic importance does not suffice to translate into increasing political power to shape economic policy making when it comes to state aid or public procurement. Once more in line with our second hypothesis, liberalised trade in machinery between the EU and Ukraine has thus far not helped to break up the institutional status quo of Ukraine’s LAO.

With regard to Ukraine’s four leading export sectors to the EU, we do not have convincing evidence that prior to (or shortly after) trade liberalisation with the EU the (old) dominant elites increased their stakes in sectors that they expected to benefit most from trade liberalisation. Mergers and acquisitions, which took place from 2008 to 2014 by Ukraine’s financial and industrial groups cannot be directly linked to the expected launch of the DCFTA. In order to overcome trade barriers and to increase the market share on the EU market long before DCFTA, they rather bought EU companies, particularly, in the steel sector long before the DCFTA entered into force.Footnote16

Overall, it is also quite notable that the distinction between dominant and rival elites in the Ukrainian context is blurred when it comes to rent-seeking. Under Poroshenko government policies often benefitted both dominant and rival elites because rival elites have formed (arguably, not for the first time) an informal alliance with the current dominant elites, that largely used to represented by former President Petro Poroshenko. Preferred treatment of new elites (when it comes to state aid or tax concessions) is balanced with similar concessions to the old elites and similarly, the new elites tend to refrain from legal persecution of the old elites. Considering the pervasive nature of high-level corruption, some scholars argue that the focus on prevention rather than on punitive measures could lay the basis for a compromise in Ukraine’s fight against corruption (Lough and Dubrovskiy Citation2018).

Summing up, our findings are ambivalent. Trade liberalisation between Ukraine and the EU in the context of the DCFTA contributed positively to Ukraine’s trade balance and helped to offset the effects of reduced trade with Russia, especially since 2014. An unintended side effect is, however, that trade liberalisation with the EU mainly benefited politically connected companies, who can abuse their economic power for rent-seeking and are part of or remain loyal to the dominant elite running the country. During Petro Poroshenko’s term in office trade liberalisation between the EU and Ukraine has first and foremost benefited big firms owned by members of Ukraine’s dominant or rival elites with stakes in the four leading export sectors. They used their fortune and economic importance to shape Ukrainian politics and policies for the sake of private gains, thereby limiting access to economic and political resources. More precisely, in the agrifood sector, trade liberalisation has helped to empower allies of a dominant elite under President Poroshenko. In other sectors, such as metals and minerals, trade liberalisation helped to consolidate the institutional status quo by benefitting allies of the previous dominant elite that used to be close to former President Yanukovich. They, however, did not challenge the dominant elite during Poroshenko’s term.

That said, we also found that the agrifood sector, which is the sector that benefited most from trade liberalisation with the EU, as it witnesses increasing export volumes, is more diversified in terms of ownership structure than the previous key sectors, metals and mining. True, the big agrifood holdings belonging to Ukrainian oligarchs have been able to increase their share in food exports to the EU, as trade became more liberalised. They use their economic power for rent-seeking. But trade liberalisation has also made it more difficult to apply discriminatory measures against foreign firms in the form of export duties and has given rise to new economic actors, mainly SMEs, in niche export sectors such as dairy and fruits. A similar trend applies to the machinery sector. While trade liberalisation with the EU has neither weakened nor strengthened the key owners enjoying close ties with the dominant elites under Yanukovich and Poroshenko, respectively, it has helped to increase the export shares of SMEs as a result of growing foreign investments. Hence, a relatively small but increasing number of economic actors enjoys access to economic resources. Whether greater economic access in selected sectors also translates into political access remains to be seen.

It also remains to be seen whether the 2019 election of Volodymyr Zelenskiy as new President of Ukraine and the victory of his Servant of the People party at the parliamentary elections of June 2019 will lead to more economic and political opening. On the one hand, oligarch Ihor Kolomoisky has not (yet) enjoyed privileged treatment despite his assumed ties to Zelenskiy. On the other hand, the fight against high-level corruption and clientelism is still mainly happening on paper.

4. Conclusion

This paper investigated whether trade liberalisation contributes to or undermines economic opening and how this affects access to political resources in LAOs. By focusing on the case of trade liberalisation between the EU and Ukraine in the context of Ukraine’s WTO membership (2008) and the conclusion of the DCFTA (2014), we investigated this question on the basis of a most likely case for observing a positive causal relationship between trade liberalisation and opening.

We show that the quality of pre-existing alliances between political and economic elites in key exporting sectors determines whether trade liberalisation helps to facilitate opening. Since Ukraine’s main exporting sectors to the EU are dominated by rent-seeking economic elites with close ties to the political elites, trade liberalisation between the two parties has so far helped to consolidate the pre-existing status quo of limited access to economic and political resources. Only in some sub-sectors of Ukraine’s agrifood industry which are characterised by a more diversified ownership structure, trade liberalisation has given rise to new economic actors who do, however, not enjoy ties to the dominant political elite.

Our findings suggest an important avenue for future research, namely to systematically examine additional scope conditions under which trade liberalisation with democracies can contribute to economic and political opening in a LAO. According to the existing literature, the way external actors tie trade liberalisation to transnational regulatory integration and the provision of assistance for enabling a broad group of domestic economic actors to reap the benefits of trade liberalisation may be key in this respect (Bruszt and Langbein, Citation2020).

Notwithstanding, our findings already hold important implications for the governance of transnational markets in the post-Soviet space: Our analysis suggests that external actors, such as the EU, wishing to support opening in LAOs through trade liberalisation must not ignore the ownership structure of key exporting sectors and the involvement of these key owners in rent-seeking practices. As we have shown, trade liberalisation can empower the wrong actors in such a context. We can certainly expect similar or even worse effects in LAOs like Georgia or Moldova. The latter two equally suffer from rent-seeking and state capture and have witnessed similar degrees of trade liberalisation as Ukraine in the context of their DCFTAs with the EU. At the same time, they receive far more limited support from Brussels when it comes to broadening the group of domestic actors building developmental capacities to reap the benefits of the DCFTA (Wolczuk et al. Citation2017).

But even for Ukraine our findings imply that recent reforms of EU assistance for state building (Wolczuk et al. Citation2017) need to continue to bring about a more autonomous Ukrainian state that is capable to fend off capture by vested interests. More targeted assistance for creating and strengthening units within the state that are capable to plan and promote strategies for inclusionary development benefitting a broad range of economic actors is needed to avoid that market opening (unintentionally) helps to consolidate the institutional status in LAO. More specifically, the EU could help to prevent rent-seeking opportunities in major exporting sectors by discouraging preferential use of state aid or the capture of government assets. Some ongoing initiatives in Ukraine that include establishing new institutions for public procurement, such as ProZorro, or outsource certain procurement to international organisations, as recently happened with medical procurement, go into the right direction in that respect.

Last but not least, the EU needs to provide even more targeted support to SMEs in terms of access to finance and to professional services. This particularly applies to sectors like dairy, meat or machinery in which SME integration in value chains is already happening. Notably, the “export success” of Ukrainian poultry producer MHP owned by oligarch Yuriy Kosyuk was to a large extent possible due to loans from the International Finance Corporation (IFC) and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD). Their loans contributed significantly to the modernisation of MHP’s production facilities. Providing more funds to SMEs will increase the administrative burden for these and other creditors but bring them closer to their goal to further political and economic competition in countries like Ukraine.

Acknowledgements

We thank Tanja Börzel, Antoaneta Dimitrova, Ann-Sophie Gast, Julian Hinz and Frank Schimmelfennig for very helpful comments on an earlier draft of this paper. The usual disclaimer applies. Excellent research assistance by Hannah Fabri, Johannes Hecker and Sarah Pfaffernoschke is gratefully acknowledged. Research for this paper has been supported by the Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme of the EU (project “The European Union and Eastern Partnership Countries – An Inside-Out Analysis and Strategic Assessment” [EU-STRAT]) under grant agreement number 693382 (www.eu-strat.eu). This article reflects solely the views of the authors and the European Commission is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Julia Langbein

Julia Langbein is senior researcher at the Center for East European and International Studies (ZOiS), Berlin. She holds a PhD from the European University Institute in Florence (Italy). Her research focus lies in the field of comparative political economy (with a focus on Eastern Europe), European integration and institutional development. Her latest publications include Market integration and room for development in the peripheries, Review of International Political Economy, 2020 (with László Bruszt); Core–periphery disparities in Europe. Is there a link between political and economic divergence?, West European Politics, 2019 (with Tanja Börzel) and Varieties of Limited Access Orders. The nexus between politics and economics in hybrid regimes, Governance, 2019 (with Esther Ademmer and Tanja Börzel). Langbein’s work has also appeared in the Journal of European Public Policy, Journal of Common Market Studies, Europe-Asia Studies and Eurasian Geography and Economics.

Ildar Gazizullin

Ildar Gazizullin is a specialist in economic policy analysis at the Ukrainian Institute for Public Policy (UIPP). He received his MA degree in economic theory from Kyiv Mohyla Academy. His research interests cover Ukraine-EU relations, energy, macroeconomic forecasting and social cohesion. Gazizullin has co-authored papers on Ukraine’s membership in the Energy Community Treaty and the EU-Ukraine Free Trade Agreement.

Dmytro Naumenko

Dmytro Naumenko is an associate analyst at the Ukrainian Institute for Public Policy and a senior analyst at the Ukrainian Centre for European Policy (UCEP). Naumenko received his MA degree in finance from Kyiv National Economic University. His research focus lies in European integration of Ukraine, energy policy and the financial sector.

Notes

1 Here we refer not to exports to the world but to exports to the trading partner with which trade liberalisation was negotiated. In the case of Ukraine, the structure of Ukraine’s exports to the EU resembles the structure of Ukraine’s total exports.

2 In this context rents refer primarily to rents sought and obtained through trade by politically connected businesses via preferential access to state aid, public procurement contracts, or the like.

3 We have not looked at trade in services because Ukraine clearly specializes in the exports of goods. The share of exports of services to the EU in overall exports constituted about 17% and has been relatively stable over the past 10 years. That said, the IT sector (software development), which has become one of Ukraine’s major export sectors in services, is characterized by a diversified ownership structure. However, EU-Ukraine trade in IT services does not suffer from trade barriers and hence trade negotiations have hardly focused on this sector with the exception of intellectual property rights protection. It is therefore not a suitable case for analysing the effect of trade liberalisation on political and economic opening.

4 ATP expired on 1 January 2016, when the DCFTA as a whole entered provisionally into force after a delay under a trilateral agreement between Ukraine, the EU and Russia on 12 September 2015. The EU removed customs duties on more than 80% of exports to the EU which make up for more than one third of all Ukrainian exports (see Council of the European Union Citation2014).The import duties have also decreased under the Association Agreement, especially for agricultural products (from some 20% to below 1%). Since non-tariff barriers were also relaxed, Ukraine’s key export-driven sectors (agrifood, machinery and chemicals) got an additional boost (see Council of the European Union Citation2014).

5 EU tariff-rate quotas (TRQs) cover: Animal products: meat (beef, pork, sheep, poultry), milk and dairy,

eggs, honey etc. – Plant products: grains (wheat, barley, oat, maize), mushrooms, garlic etc. – Processed

food and other products: sugar and products, grape and apple juice, sweet corn, processed tomatoes,

ethanol, cigarettes etc. (cf. Movchan, Kosse, and Giucci Citation2015).

6 By contrast, only 38.5% of SME respondents indicated that they were exporting to CIS countries.

7 Expert interview, Kyiv, November 2018.

8 In December 4, 2012, the European Commission’s Directorate General for Health and Consumer Protection included Ukraine into the list of third countries eligible to export poultry products to the EU (see Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine Citation2013).

9 After exceeding the TRQ for chicken breasts (that is the main and most valuable product of MHP) in 2014 the company started to use the second TRQ line, namely breast with a piece of wing bone attached, supplying the bony cuts to its own processing plants in the EU, cutting off the bones and reselling them as chicken breasts afterwards. As a result, MHP exports to EU-28 under this new category has increased from 3.5 thousand tons in 2016 to around 27 thousand tons in 2017. This case has been reviewed in the European Parliament as local producers raised a concern that poultry imports from Ukraine could destabilise the EU internal market (European Parliament Citation2018).

10 Numerous export lines exist for fruits, berries, vegetables, nuts and others.

11 While in 2000, the EU imposed an import tariff of 93% on Ukrainian dairy products, the tariff was reduced to 25% following Ukraine’s accession to the WTO (Langbein Citation2015).

12 Notably, Ukraine’s dairy market is not highly concentrated: The top-10 large companies share did not exceed 10% each in 2017 (Latifundist.com Citation2018b).

13 Some owners had to exit from a number of businesses (partially or totally) as they became loss-making: e.g., Industrial Union of Donbas in 2010 and Privat Group over 2009–2016.

14 For example, it was a by-product of a large MMK steel plant acquisition by SCM in 2010, which resulted in the SCM group creating the agricultural holding HarvEast in 2011, the core assets of which were based on a land bank, previously managed by MMK.

15 Total investments are estimated at over €500 million. Investors (over 28 global and European companies) tend to focus on assembly of electrical appliances or car components, predominantly in Western Ukraine (Strategy Council Citation2019).

16 For instance, Metinvest (SCM group) acquiring Ferriera Valsider in Italy in 2012 or Industrial Union of Donbas Huta Czestochowa in Poland in 2005.

References

- Ademmer, E., J. Langbein, and T. A. Börzel. 2019. “Varieties of Limited Access Orders: The Nexus Between Politics and Economics in Hybrid Regimes.” Governance 33: 191–208. doi: 10.1111/gove.12414

- Adserà, A., and C. Boix. 2002. “Trade, Democracy, and the Size of the Public Sector: The Political Underpinnings of Openness.” International Organization 56 (2): 229–262. doi:10.1162/002081802320005478.

- Agrobusiness of Ukraine. 2018. Infographichnyi dovidnik Agrobiznes Ukrainy u 2017-2018 marketingovmu rotsi [Bulletin Agrobusiness of Ukraine in 2017/2018 Marketing Year]. Kyiv: Latifundist Media. Accessed 25 March 2018. https://agribusinessinukraine.com/the-infographics-report-ukrainian-agribusiness-2018/.

- Amable, B., and S. Palombarini. 2009. “A Neo-Realist Approach to Institutional Change and the Diversity of Capitalism.” Socio-Economic Review 7 (1): 123–143. doi:10.1093/ser/mwn018.

- Balabushko, O., O. Betliy, V. Movchan, R. Piontkivsky, and M. Ryzhenkov. 2018. “Crony Capitalism in Ukraine: Relationship between Political Connectedness and Firms’ Performance.” Policy Research Working Paper 8471, Washington, D.C.; Kiev: World Bank, Institute for Economic Research and Policy Consulting.

- Balmaceda, M. M. 2013. The Politics of Energy Dependency: Ukraine, Belarus, and Lithuania between Domestic Oligarchs and Russian Pressure. Studies in Comparative Political Economy and Public Policy. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Bessonova, E., O. Merschenko, and N. Gridchina. 2015. “Ukraine in the WTO: Effects and Prospects.” Romanian Journal of European Affairs 15 (3): 66–83.

- Birnbaum, M. 2014. “Ukraine factories equip Russian military despite support for rebels” Washington Post, August 15. Accessed 25 March 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/europe/ukraine-factories-equip-russian-military-despite-support-for-rebels/2014/08/15/9c32cde7-a57c-4d7b-856a-e74b8307ef9d_story.html?noredirect=on&utm_term=.66986121578e.

- Börzel, T., and Y. Pamuk. 2012. “Pathologies of Europeanization. Fighting Corruption in the Southern Caucasus, co-Authored with Yasemin Pamuk.” West European Politics 35 (1): 79–97. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2012.631315

- Bruszt, L., and J. Langbein. 2017. “Varieties of Dis-Embedded Liberalism. EU Integration Strategies in the Eastern Peripheries of Europe.” Journal of European Public Policy 24 (2): 297–315. doi:10.1080/13501763.2016.1264085.

- Bruszt, L., and J. Langbein. 2020. “Manufacturing Development. How Transnational Market Integration Shapes Opportunities and Capacities for Development in Europe's Three Peripheries.” Review of International Political Economy. doi:10.1080/09692290.2020.1726790.

- Całus, K., L. Delcour, I. Gazizullin, T. Iwański, M. Jaroszewicz, and K. Klysiński. 2018. “Interdependencies of Eastern Partnership Countries with the EU and Russia: Three Case Studies.” EU-STRAT Working Paper No. 10, Berlin: Freie Universität Berlin.

- Connolly, R. 2013. The Economic Sources of Social Order Development in Post-Socialist Eastern Europe. BASEES/Routledge Series on Russian and East European Studies. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Council of the European Union. 2014. “Ukraine: unilateral trade measures extended.” Press release, ST 14689/14 PRESS 554, 24 October, Brussels. Accessed 25 March 2019 https://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/EN/foraff/145390.pdf.

- Doner, R. F., and B. R. Schneider. 2016. “The Middle-Income Trap: More Politics Than Economics.” World Politics 68 (4): 608–644. doi:10.1017/S0043887116000095.

- EasyBusiness Guidebook. 2018. Integratsia ukrainskogo msb v lantsugi dodanoi vartosti Yees [Entering EU Markets for the Ukrainian SMEs]. Kyiv: EasyBusiness.

- Emerson, M., T. H. Edwards, I. Gazizullin, M. Lücke, D. Müller-Jentsch, V. Nanivska, V. Pyatnytskiy, et al. 2006. “The Prospects of Deep Free Trade between the EU and Ukraine.” CEPS Paperback. Brussels: Centre for European Policy Studies.

- European Commission. 2013. “Amending Decision 2007/777/EC and Regulation (EC) No 798/2008 as regards the entries for Ukraine in the lists of third countries from which certain meat, meat products, eggs and egg products may be introduced into the Union Text with EEA relevance.” Commission implementing Regulation (EU) No 88/2013, 31 January, Brussels: Official Journal of the European Union.

- European Commission. 2015. “Opening and Providing for the Administration of Union Import Tariff Quotas for Poultry Meat Originating in Ukraine.” Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2015/2078, 18 November, Brussels: Official Journal of the European Union.

- European Parliament. 2018. “Answer given by Mr Hogan on behalf of the Commission.” Accessed 20 January 2019. http://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/P-8-2018-002303-ASW_EN.html?redirect.

- Eurostat. 2019. “International Trade in Goods.” Accessed 20 January 2019. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/international-trade-in-goods/data/database.

- Frye, T., and E. D. Mansfield. 2003. “Fragmenting Protection: The Political Economy of Trade Policy in the Post-Communist World.” British Journal of Political Science 33 (4): 635–657. doi:10.1017/S0007123403000292.

- Gudz’, I. 2018. “Ect’ li mecto ukrainskomu malomu i srednemy biznesu na rynke Evrosoyuza? [Is there room for Ukrainian SMEs on the EU market?]” Delo, August 13. Accessed 25 March 2019. https://delo.ua/business/est-li-mesto-ukrainskomu-malomu-i-srednemu-biznesu-na-rynke-evr-342134/.

- Hale, H. 2014. Patronal Politics. Eurasian Regime Dynamics in Comparative Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge, UP.

- Helleiner, G. K. 1994. Trade Policy and Industrialisation in Turbulent Times. London: Routledge.

- Hellman, J. S. 1998. “Winners Take All: The Politics of Partial Reform in Postcommunist Transitions.” World Politics 50 (2): 203–234. doi:10.1017/S0043887100008091.

- Hirschman, A. O. 1968. “The Political Economy of Import-Substituting Industrialization in Latin America.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 82 (1): 1–32. doi:10.2307/1882243.

- Hoekman, B., J. Jensen, and D. Tarr. 2014. “A Vision for Ukraine in the World Economy.” Journal of World Trade 48 (4): 795–814.

- Horovetska, Y., B. Rudloff, and S. Stewart. 2017. “Agriculture in Ukraine: Economic and Political Frameworks.” SWP Working Paper. Berlin: Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik (SWP).

- IMF. 2016. “The Impact of Trade Agreements: New Approach, New Insights.” IMF Working Paper Strategy, Policy and Review Department, WP/16/117, June 10. Accessed 25 March 2019. http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/960821480958611562/5-Swarnali-paper.pdf.

- Kobuta, I., O. Sikachyna, and V. Zhygadlo. 2012. “Wheat export economy in Ukraine.” Policy Studies on Rural Transition, No. 2012:4. Budapest: FAO Regional Office for Europe and Central Asia.

- Kovensky, J. 2017. “Vested interests blocking agricultural land market.” Kyiv Post, November 3. Accessed 20 January 2019. https://www.kyivpost.com/business/vested-interests-blocking-agricultural-land-market.html.

- Kupfer, M. 2018. “Harvest Of Cash: Big Agroholdings use Political Clout to reap sweet Subsidies from Ukraine’s Taxpayers.” Kyiv Post, November 16. Accessed 20 January 2019. https://www.kyivpost.com/business/big-agroholdings-use-political-clout-to-reap-sweet-subsidies-from-ukraines-taxpayers.html?fbclid=IwAR0Qv2ebixFU9jyHayou6UviRzaGgSmHWzw8M1vPnVGB6-tHPX8JipJMQCM.

- Langbein, J. 2015. Transnationalization and Regulatory Change in the EU’s Eastern Neighbourhood. Ukraine between Brussels and Moscow. London: Routledge.

- Langbein, J. 2016. “(Dis-)Integrating Ukraine? Domestic Oligarchs, Russia, the EU and the Politics of Economic Integration.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 57 (1): 19–42. doi:10.1080/15387216.2016.1162725.

- Latifundist.com. 2013. “TOP 20 proizvoditelei molochnoi i molokosoderzhashei produktsii 2012 [TOP 20 milk and milk containing products’ producers in 2017].” March 22. Accessed 20 January 2019. https://latifundist.com/rating/top-20-proizvoditelej-molochnoj-produktsii-ukrainy.

- Latifundist.com. 2018a. “TOP 15 Wheat Exporters in 2016/2017.” March 8. Accessed 20 January 2019. https://latifundist.com/en/rating/top-15-eksporterov-pshenitsy-za-201617-mg.

- Latifundist.com. 2018b. “TOP 10 proizvoditelei molochnoi i molokosoderzhashei produktsii 2017 [TOP 10 milk and milk containing products’ producers in 2017].” March 28. Accessed 20 January 2019. https://latifundist.com/rating/top-10-proizvoditelej-molochnoj-i-molokosoderzhashchej-produktsii-2017.

- Levitsky, S., and L. Way. 2010. Competitive Authoritarianism: Hybrid Regimes After the Cold War. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Lewis, R. 2018. “The Vicious Circle: How Financing From IMF and Other Financial Institutes Feeds Corruption In Ukrainian Agricultural Sector.” EU today, June 12. Accessed 25 March 2019. https://eutoday.net/news/politics/2018/the-vicious-circle-how-financing-from-imf-and-other-financial-institutes-feeds-corruption-in-ukrainian-agricultural-sector.

- Lipset, S. M. 1959. “Some Requisites of Democracy: Economic Development and Political Legitimacy.” The American Political Science Review 53 (1): 69–105. doi:10.2307/1951731.

- Lough, J., and V. Dubrovskiy. 2018. “Are Ukraine’s Anti-Corruption Reforms Working?” Research Paper Russia and Eurasia Programme. London: Chatham House.

- Manger, M. S., and M. Pickup. 2016. “The Coevolution of Trade Agreements and Democracy: A Simulation-Based Approach.” The Journal of Conflict Resolution 60 (1): 164–191. doi:10.1177/0022002714535431.

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine. 2013. “European Union gives green light to Ukrainian poultry export.” July 23. Accessed 25 March 2019. https://uk.mfa.gov.ua/en/press-center/ukraine-digest/19-issue-18-july-25-2013/153-european-union-gives-green-light-to-ukrainian-poultry-export.

- Movchan, V. 2007. “Impact of Ukraine’s WTO Accession.” In Beyond Transition 18 (4): 21–22.

- Movchan, V., I. Kosse, and R. Giucci. 2015. “EU Tariff Rate Quotas on Imports from Ukraine.” Policy Briefing Series [PB/06/2015]. Berlin/Kyiv: German Advisory Group Ukraine.

- North, D. C., J. J. Wallis, and B. R. Weingast. 2009. Violence and Social Orders: A Conceptual Framework for Interpreting Recorded Human History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Patrioty.org.ua. 2018. “Liubi Druzi: yak bisnes partnery Poroshenka kotrolyuyut milyardni zamovlennia Ukroboronpromu [Dear Friends: how business partners of Poroshenko control UkrOboronProm’s procurement worth billions].” December 1. Accessed 20 January 2019. http://patrioty.org.ua/blogs/liubi-druzi-iak-biznes-partnery-poroshenka-kontroliuiut-miliardni-zamovlennia-ukroboronpromu-144623.html.

- Richter, S., and N. Wunsch. 2020. “Money, Power, Glory: the Linkages Between EU Conditionality and State Capture in the Western Balkans.” Journal of European Public Policy 27 (1): 41–62. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2019.1578815

- Shyrokykh, K. 2017. “Effects and Side Effects of European Union Assistance on the Former Soviet Republics.” Democratization 24 (4): 651–669. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2016.1204539

- SIPRI. 2019. “Trends in International Arms Transfers: 2018.” SIPRI Fact Sheets, March 2019. Accessed 25 March 2019. https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2019-03/fs_1903_at_2018_0.pdf.

- Smits, K., E. M. Favaro, A. Golovach, F. Khan, D. F. Larson, K. Govchuk Schroeder, G. Schmidt, et al. 2019. Ukraine Growth Study Final Document: Faster, Lasting and Kinder (English). Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/543041554211825812/Ukraine-Growth-Study-Final-Document-Faster-Lasting-and-Kinder.

- Stahl Centrum. 2019. “EU-28: Steel foreign trade.” Accessed 25 March 2019 https://en.stahl-online.de/index.php/statistics/5/.

- State Statistics Service. 2019. “Statistical Yearbook of Ukraine.” State Statistics Service of Ukraine. Accessed 20 January 2019. www.ukrstat.gov.ua/.

- Strategy Council. 2019. “Data on Foreign Investors in Ukrainian Automotive Industry.” Accessed 20 January 2019. http://strategy-council.com/files/research/uk/27.pdf.

- Strubenhoff, H. 2017. “Creating markets in times of crises: Connecting Ukrainian farmers to the world.” Brookings, April 20. Accessed 25 March 2019. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2017/04/20/creating-markets-in-times-of-crises-connecting-ukrainian-farmers-to-the-world/.

- Trade Control and Export System. 2019. “Trade control and export system of the European Union.” Accessed 20 January 2019. https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/sanco/traces/output/UA/MMP_UA_en.pdf.

- Ukrpravda. 2017. “Kosyuk za pivroku otrymav z byudzhetu 42% vsih dotatsiy dlya agrariiv [Kosyuk got 42% of all state aid in agriculture over half a year].” August 21. Accessed 20 January 2019. https://www.epravda.com.ua/news/2017/08/21/628247/.

- UNEP. 2018. “Green economy options for Ukraine: Opportunities for organic agriculture.” Policy Brief, Geneva-Kyiv. Accessed 25 March 2019. http://www.green-economies-eap.org/resources/Ukraine%20OA%20ENG%2027%20Jun.pdf.

- Voloshin, P. 2017. “Top-10 exporters of grain from Ukraine.” National Industrial Portal, August 4. Accessed 20 March 2019. http://uprom.info/en/news/agro/top-10-kompaniy-eksporteriv-zernovih-z-ukrayini/.

- Wolczuk, K., L. Delcour, R. Dragneva, K. Maniokas, and D. Žeruolis. 2017. “The Association Agreements as a Dynamic Framework: Between Modernization and Integration.” EU-STRAT Working Paper No.6. Berlin: Freie Universität Berlin.

- Wolczuk, K., and D. Zeruolis. 2018. “Rebuilding Ukraine: an Assessment of EU Assistance.” Chatham House Research Paper. Accessed 8 February 2019. https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/publications/research/2018-08-16-rebuilding-ukraine-eu-assistance-wolczuk-zeruolis.pdf.

- World Bank. 2004. “Ukraine - Building foundations for Sustainable Growth: a Country Economic Memorandum.” December 27. Accessed 20 March 2019. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/239181468778161511/Ukraine-Building-foundations-for-sustainable-growth-a-country-economic-memorandum.