ABSTRACT

The democratic performance is declining across a number of Central and Eastern European Member States of the European Union, this while regime support has seemingly been steadily increasing. This dual development leads to questions regarding whether the democratic performance actually matters for regime support within a region consisting of countries that are still being considered as relatively new democracies. The findings from this study shows that there is a negative connection between higher levels of democratic performance and regime support within the countries in this region during the period of 2004–2019. Nonetheless, higher levels of democratic performance are still related to higher levels of regime support across the region.

Introduction

Public support for democracy as a system of governance remains high across Europe (Claassen Citation2019; Diamond Citation2015; Norris Citation2011) and it has been suggested that the status of democracy in Europe is more stable than in other regions (Rupnik Citation2007, 25). Moreover, a membership to the European Union (EU) has been considered as an anchor that supposedly stabilises the liberal form of democracy within the Member States (Brusis Citation2016; Cirtautas and Schimmelfennig Citation2010; Rupnik Citation2007; Rupnik and Zielonka Citation2013). Nevertheless, there are some worrying signs in terms of the actual democratic performance across the EU (Sitter and Bakke Citation2019). These signs are the most straightforward across Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), where a growing number of Member States are considered to be heading towards a democratic recession (Cianetti, Dawson, and Hanley Citation2018; Dawson and Hanley Citation2016; Matthes Citation2016; Sedelmeier Citation2014; Stanley Citation2019). The most noteworthy example is Hungary, which in 2020 became the first EU Member State labelled as an electoral authoritarian regime by the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) dataset (Lührmann et al. Citation2020). Moreover, after the Law and Justice Party (PiS) returned to power in Poland 2015, they have “embarked on a programme of illiberal reforms that rivalled Fidesz for ambition and led to a decline in the quality of democracy swifter and steeper than that observed in Hungary” (Stanley Citation2019, 349). Hence, both countries are now more or less perceived as cases of “intentional subversion and capture of liberal democratic institutions” (Stanley Citation2019, 351). Hanley and Vachudova (Citation2018, 277) further suggests that the current direction in the Czech Republic, with a government coalition led by ANO and Prime Minister Andrej Babiš, is slowly turning the Czech Republic into, what they refer to as, a populist democracy. This is a remarkable development in a region previously considered as constituting a democratic success story (Cianetti, Dawson, and Hanley Citation2018, 244).

Subsequently, there has been a growing scholarly interest in the social- and political effects derived from these developments across the Central and Eastern European (CEE) EU Member States during the last decade (e.g. Matthes Citation2016; Stanley Citation2019). Notwithstanding the aforementioned countries, there are significant variations in regards to the patterns of democratic performance observed across this region (Stanley Citation2019, 344). Furthermore, democratic regimes are considered to be especially dependent on regime support (Mishler and Rose Citation2002) but the macro-level connection between democratic performance and regime support across a regional CEE setting has so far received limited attention (but see Christmann Citation2018; Wagner, Schneider, and Halla Citation2009). Within the subsequent study, the regimes may or may not be democratic, and the concept of regime support is therefore used as an indication of the proportion of citizens supporting the regime, irreversibly of regime type. The research aim of the present study is therefore to test the connection between democratic performance and regime support across the CEE region over time.

The research approach is limited to study this phenomenon within the context of the post-communist EU Member States from the CEE region. These are countries that has been previously considered to be among the post-communist world’s most stable democracies (Cianetti, Dawson, and Hanley Citation2018, 243) and now share more common features with other EU countries than with non-EU post-communist countries (Brusis Citation2016; Rupnik and Zielonka Citation2013). Even so, this region consists of countries that have developed both politically and socioeconomically in different directions during especially the last 15 years (Bochsler and Juon Citation2020). Furthermore, by limiting the study to these countries it becomes possible to account for the EU membership factor, as these countries together constitute the newest democracies in the EU. This is also a regional cluster where significant variations in the main explanatory variable, democratic performance, has been observed during the period of interest (Lührmann et al. Citation2020; Stanley Citation2019). Considering everything, this constitutes an adequate regional setting for this type of explanatory study. As the presence of sufficient levels of regime support is especially important for democratic consolidation within new, or transitional, democracies (Welzel Citation2007), the altogether eleven countries constitute an optimal regional setting for studying the connection between democratic performance and regime support.

The research question that this study seeks to answer is how does the democratic performance affect regime support within and between post-communist countries? Moreover, by taking both a longitudinal and cross-national approach, this study seeks to identify and explain general patterns across the CEE region regarding the macro-level connection between regime support and regime performance and to what extent varied contextual influences matter for regime support. This article is divided into five main sections. The first section will present the main political developments across the CEE region post 2004. The second section will focus on what earlier studies have shown in terms of country-level variations in regime support. The third section presents the research design, the dependent and independent variables, the data and the statistical multilevel regression model. The fourth section presents the main findings and the final section concludes with a general discussion regarding the main limitations and contributions derived from the study.

Democratic performance across CEE

A well-functioning democratic system is expected to possess a good balance between freedom, equality and control, and the main difference between a democracy and an autocracy is that the people are expected to constitute a check on the power within a democracy (Bühlmann et al. Citation2012). Hence, a democratic system is expected to sustain itself by effective self-control and rule enforcement by the public (Bernhard Citation2020, 353). When a country reaches this status it is usually being referred to as a consolidated democracy, which indicates that democracy has become the only realistic alternative of governance. Once a country becomes a consolidated democracy, the risk of democratic regression is considered slight (Linz and Stepan Citation1996, 14). Democratic backsliding is a term used to describe an ongoing process of de-democratisation or democratic regression, even if there is no clear scholarly consensus regarding how to define this process. In a broad sense, this type of process at least includes “any change of the formal or informal rules that constitute a political community which reduces that community’s ability to guarantee the freedom of choice, freedom from tyranny, or equality in freedom to citizens and groups of citizens” (Jee, Lueders, and Myrick Citation2019, 1).

Consequently, democratic backsliding contributes to a stepwise dismantling of societal elements that the citizens living within democracies are supposed to cherish. Bermeo (Citation2016, 5) identifies democratic backsliding as “state-led debilation or elimination of any of the political institutions that sustain an existing democracy”. Moreover, Sitter and Bakke (Citation2019, 4) suggests that the process of democratic backsliding at any rate involves some key features, such as a decline in the quality of rule of law and the democratic processes, usually combined with an increasing concentration of political power. They further argue that this is a process that can be proceeded step wise, openly and deliberately. Although, most scholars seem to agree that the process of democratic backsliding occurs gradually and mostly under some form of legal disguise (Lührmann and Lindberg Citation2019, 1095). Thus, democratic backsliding will in this study be used as a concept for describing an (1) ongoing process that is (2) deliberative and results in the eventual (3) weakening of democracy.

After the end of the Cold War, the CEE countries entered a phase of market liberalisation, followed by a period of democratic transition before finally entering a phase of democratic consolidation when the EU accessions finally materialised after 2004 (Cirtautas and Schimmelfennig Citation2010, 422). Initially an EU membership was considered as being extra important for consolidating democracy in these countries, as many of them were experiencing domestic contestation between liberal and authoritarian political alternatives during the democratic transition period (Sedelmeier Citation2014). Nonetheless, after the EU memberships materialised most of these countries have become regarded as “normal countries”, in the West European normative sense of the meaning (Schleifer and Treisman Citation2014, 93). At least prior to the Global Recession (2007–2009), and the following Eurocrisis (2010–2012), most of the CEE countries were booming with the standard of living rising extensively across the region (Krastev Citation2007, 58). Therefore, the period between the end of the Cold War and the years following the EU accessions can broadly be described as a honeymoon-period for the CEE region and these countries were widely considered as constituting democratic success stories (Cianetti, Dawson, and Hanley Citation2018, 244).

The Global Recession finally ended this honeymoon-period, as most CEE countries were forced to implement though austerity measures and unpopular structural reforms just in order to cope with the economic challenges during the financial crises (Armingeon and Guthmann Citation2014, 423). Moreover, the financial crises had a significantly negative effect on how the EU was perceived by the public across this region (Karv Citation2019; Van Erkel and Van der Meer Citation2016). Another important indirect consequence derived from the financial crises was that the EU friendly political elites lost much of their credibility across the region (Matthes Citation2016, 331). Thus, it has been argued that the financial crises started a process that has eventually contributed to the weakening of the liberal form of democracy across the CEE region (Brusis Citation2016; but see Bochsler and Juon Citation2020). Hence, the CEE region is now facing serious democratic difficulties (Cianetti, Dawson, and Hanley Citation2018, 244).

Still, over a decade ago Krastev (Citation2007, 56) already declared that the liberal era had ended within the CEE region while some even questioned whether liberal democracy was ever really institutionalised to begin with (Dawson and Hanley Citation2016, 25). According to Mungiu-Pippidi (Citation2007, 16), these countries might have acted nice during the EU admission-discussions, but once they were accepted they gradually started to “return to their old ways”. One of the main reasons why the EU have not been able to counter this development is because even if “EU law provides the EU with a limited set of enforceable standards, it simply does not have comparably strong and comprehensive mechanisms for putting countries under pressure once admitted” (Batory Citation2018, 179). Hence, as further suggested by Mungiu-Pippidi (Citation2007, 16), “when conditionality has faded, the influence of the EU vanishes like a short-term anesthetic”. Subsequently, it has now become evident that the EU should not be regarded as a guarantor for the survival of liberal democracy within the Member States (Uitz Citation2015, 283). Still, an EU membership might still be perceived as some kind of assurance for these countries not to develop into full-blown dictatorships (Keleman Citation2020, 495).

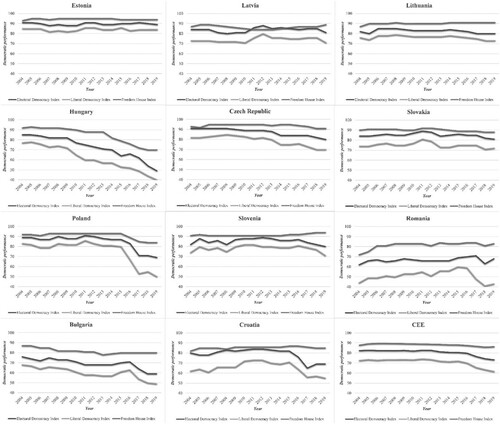

Anyhow, it is important to remember that after 30 years of democracy the differences between these countries have also grown. Hence, even if these countries all share a post-communist political heritage there are significant variations in terms of both the political and societal developments across the CEE region post EU-accessions. Looking at the specific countries, and according to Stanley (Citation2019), Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovenia and Slovakia can now all be considered as constituting stable democracies, as these countries are showing little signs of democratic backsliding. However, based on the ongoing political developments across Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland, Stanley (Citation2019) suggests that these countries now clearly constitute backsliding democracies, showing evident signs of democratic backsliding. This is particularly interesting, as both Hungary and Poland were previously regarded as regional leaders in terms of democratic development (Bernhard Citation2020, 348). In the Hungarian case this development has been a continuing process since 2010, and Hungary is thus a country that “has experienced particularly egregious forms of democratic backsliding” (Jee, Lueders, and Myrick Citation2019, 20). Over time, the Fidesz led government has subsequently managed to transform both the constitutional framework and system of governance in Hungary (Brusis Citation2016, 5). In terms of the three most recent EU Member States, the democratic transition within Bulgaria, Romania and Croatia have so far lagged behind the other CEE countries, and Stanley (Citation2019) therefore suggests that these three countries should be considered as “arrested developers”, so far even failing to reach even the initial status as consolidated democracies. This further increases the risk of democratic backsliding across these countries (see Appendix Figure A1 for country-level developments regarding democratic performance 2004–2019).

Regime support

The public is the only legitimate source of political power within democracies, and the public constitutes the main check on power within a democratic political system. Moreover, sufficient levels of public support is considered as critical for the viability of regimes and for the effectiveness of governing institutions within any type of political community (Easton Citation1965; Lipset Citation1959; Waldron-Moore Citation1999). It has been assumed the regime support should increase the more democratic a regime is, as a democratic regime is expected to follow the public preferences which in turn should boost support (Rose and Mishler Citation2002, 1–2). Nonetheless, even when public support for democracy remains high previously stable democracies can begin to dissolve from within due to a change in the political policies proceeded or in the public preferences (Wodak Citation2019). In order to understand the system importance of regime support, the most commonly used theoretical foundation for researchers are the works of Easton (Citation1965, Citation1975). Easton created a framework for assessing the risk of system collapse, and as a result developed the concept of system support as “the major summary variable linking a system to its environment” (Citation1965, 156). Easton’s main argument was, in short, that the lower the levels of system support the higher the risk of system collapse. Still, as a political system is too complex as a creation to be evaluated directly by the public, Easton further differentiated between three main political objects of a political system towards which support might be directed. These together constitute the main pillars of any political system: the political authorities, the political regime and the political community. In the Eastonian sense, the regime refers to the underlying fundaments of a political community, or “arrangements of authority roles” (Easton Citation1975, 448). Hence, in accordance with Easton, the regime as a theoretical concept is frequently being used in reference to a system of governance within a political community (Mishler and Rose Citation2002; Norris Citation2011) and that is also how the concept is perceived in this study.

Furthermore, in order to account for the varying levels of perceived system importance of various kinds of attitudes, Easton distinguished between two main types of support: specific and diffuse. From a system support perspective, longer periods of dissatisfaction with the political authorities will over time affect support for the regime and finally support towards the political community at the most system important, or diffuse, level. In line with this reasoning, a “decline in regime support might provoke a basic challenge to political institutions or calls for reform in government procedures” (Dalton Citation2014, 257). At that point, the foundations of the political system are severely threatened. Hence, if the political authorities are not able to counter or stop the declining levels of regime support, the long-term viability of the regime is set to become increasingly challenged. Conversely, when the political authorities responsible for governing are perceived to be performing well, it is expected to transform into support both for the governing institutions and for the underlying system of governance (Weatherford Citation1987).

Explaining country-level variations in regime support

The research interest for the subsequent study is the kind of support primarily directed towards the functioning and workings of the regime. This kind of support is more diffuse in character than support for the political authorities as it is considered to be directed towards the workings of the regime institutions, processes and principles (Norris Citation2011). Hence, country-level variations in this kind of support should be traced to the actual, or perceived, regime performances (Easton Citation1975, 448–449), and is subsequently an expression of varying public evaluations regarding the effectiveness of a regime (Klingemann Citation1999). Country levels of regime support are therefore expected to vary based on regime performances (Armingeon and Guthmann Citation2014; Christmann Citation2018; Cordero and Simón Citation2016; Van der Meer and Hakhverdian Citation2017). Hence, when there are fluctuations in regime support it is expected to be traced to contextual-level developments within the country (Easton Citation1965, 22). Still, the public differs in the emphasis put on different types of regime performances across countries (Norris Citation2011).

In line with the findings from previous studies, effective governance should result in higher levels of regime support within countries over time, independently of whether the regime is a consolidated democracy or an autocracy (Magalhaes Citation2014, 40). Across post-communist countries, it has been shown that the public primarily evaluates the regime performance based on economic or institutional developments (Mishler and Rose Citation2005; Quaranta and Martini Citation2016), and the importance of democratic performance might therefore not be as important within transitional- as within consolidated democracies (Rose and Mishler Citation2002). Nevertheless, if the public expresses high levels of support for democracy as a system of governance, which has been the case across the CEE region (Cordero and Simón Citation2016), the democratic performance might also have an impact on regime support. Consequently, negative democratic performance might contribute to lower levels of regime support when or if these developments are being felt (Magalhaes Citation2014).

According to the instrumental view of regime support, the economic performance has a significant influence on regime support within democracies, with better economic conditions creating higher levels of regime support (Magalhaes Citation2014; Quaranta and Martini Citation2016). Likewise, this has also been shown to be true within authoritarian systems (Park Citation1991, 745) and therefore, “nondemocratic regimes may enjoy a high level of political support – even while denying rights to the people – if such regimes can deliver economic well-being and good governance” (Chang, Chu, and Welsh Citation2013, 150–151). In its essence, the economic performance is a very straightforward criterion used by the public to evaluate regime performance (Van Erkel and Van der Meer Citation2016, 179). The economic performance has therefore been shown to be a strong predictor for explaining the variations in regime support over time, while the institutional quality has been better at explaining the variations between countries (Van der Meer and Hakhverdian Citation2017). Higher quality political institutions is expected to predict higher levels of regime support between countries (Anderson and Tverdova Citation2003; Van der Meer and Hakhverdian Citation2017; Wagner, Schneider, and Halla Citation2009), and better institutional performance might contribute to higher levels of regime support within countries over time (Chang, Chu, and Welsh Citation2013).

Institutional quality is often measured by levels of corruption in comparative studies and corruption levels have been shown to be a crucial determinant in cross-national analyses (Hakhverdian and Mayne Citation2012). Widespread corruption has been described as “the most pervasive threat to the rule of law” (Mishler and Rose Citation2002, 10) and ingrained institutional corruption thereby make some countries even more vulnerable for democratic backsliding (Börzel and Langbein Citation2019). Van der Meer and Hakhverdian (Citation2017, 98) explicitly suggested that the “more widespread corrupt practices are, the less citizens trust national political institutions and the less they express satisfaction with the functioning of democracy”. Furthermore, as most CEE countries suffer from culturally ingrained corruption (Batory Citation2018), regime success with solving corruption problems has been shown to result in higher levels of regime support (Linde Citation2012). Furthermore, higher levels of income inequality have been shown to evoke more positive attitudes towards non-democratic authoritarian alternatives (Solt Citation2012) while also reducing public support for democracy (Krieckhaus et al. Citation2013).

Research design, data and methods

The data set consists of a pooled sample of 11 post-communist countries, covering the period of 2004–2019. The study is therefore limited to only include countries from a region united by their shared post-communist political heritage (Rupnik Citation2007, 17), similar levels of economic development (Batory Citation2018, 169) and the EU membership. These are Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia. The empirical research purpose is to assess how time-varying contextual-level factors affect macro-level trends of regime support at two analytical levels: within countries and between countries over time. Thus, as the model deals with two substantive levels of analysis, time and countries, a multilevel method is necessary (Bliese, Chan, and Ployhart Citation2007; Snijders Citation1996).

According to Fairbrother (Citation2014, 125), using a multilevel model allows for a cross-sectional and longitudinal analysis, as “it provides a direct investigation of social change without assuming that the longitudinal relationship is the same as the cross-sectional one”. Moreover, a multilevel model is considered suitable “for analyses of complex data structures where units are grouped, and a given unit’s expected value on the dependent variable depends on the group(s) to which it belongs” (Fairbrother and Martin Citation2013, 353). Thus, this study adopts a linear mixed model (LMM), which is a statistical model that makes it possible to incorporate multilevel hierarchies in the analysis (Edwards Citation2000). By using a LMM, it becomes possible to add contextual-level covariates that are allowed to vary between countries, referred to as random effects. Moreover, a LMM is considered as “particularly suited for analyzing correlated outcomes which are continuous” (Edwards Citation2000, 334). Given that the LMM is also a very flexible regression model, it becomes particularly useful for analysing aggregated country-level dataset (Papadimitropoulou et al. Citation2019). The technique is therefore both possible and suitable to use for cross-sectional and longitudinal datasets consisting of aggregated country-level data (Snijders Citation1996, 405), but it should still be noted that it is a statistical technique that has so far been predominantly used for combining individual- with contextual level data (Fairbrother Citation2014).

The dependent variable used in the model is the aggregated year-specific country levels of regime support. Moreover, in order to differentiate between different types of regime support (Easton Citation1965; Norris Citation2011), two measurements of regime support are included: trust in government and satisfaction with how democracy works in the country (hereafter democratic satisfaction). Starting with political trust, it is derived from an evaluation of the object by a subject (Van der Meer and Hakhverdian Citation2017). There is a widespread assumption amongst scholars that trust is critical for legitimising the authority of regimes, as political trust is assumed to link ordinary citizens to the political institutions that are created to represent them, thereby enhancing both the legitimacy, stability and effectiveness of these political institutions (Mishler and Rose Citation2001, 30). In short, the presence of political trust indicates, “that members would feel that their own interests would be attended to even if the authorities were exposed too little supervision or scrutiny” (Easton Citation1975, 447). Accordingly, political trust is considered as a basic evaluative attitude towards the workings of the political institutions (Miller Citation1974, 952) and is widely used within studies as an attitudinal expression of regime support (Armingeon and Guthmann Citation2014; Norris Citation2011). In new democracies, political trust is expected to be even more critical for political stability, as these types of countries typically inherit some kind of a trust deficit from their former regimes (Linz and Stepan Citation1996; Mishler and Rose Citation2005; Rose and Mishler Citation2002). Aggregated levels of trust in government is therefore widely used in macro-level studies as a measurement of regime support (Kim Citation2010; Miller Citation1974), and will subsequently be used for that purpose here.

If trust in government is expected to reflect public evaluations of the functioning of the political institutions, democratic satisfaction closer reflects public evaluations of how the decision-making process works (Norris Citation2011, 44). Still, these two measurements of regime support have been shown to be closely correlated at the individual level (Christensen and Laegreid Citation2005). Furthermore, democratic satisfaction is understood to be more diffuse in character and thus not as prone to fluctuations, like for example trust in government (Mishler and Rose Citation2001; Norris Citation2011). Within empirical studies, survey items measuring democratic satisfaction have become widely used measurements of process-related regime support (Anderson and Tverdova Citation2003; Cordero and Simón Citation2016; Linde Citation2012; Norris Citation2011; Waldron-Moore Citation1999). Even though the word “democracy” is a symbol that individuals are prone to understand differently across countries, and hence not optimal for cross-country analyses (Mishler and Rose Citation2002, 13), this indicator is in its essence a reflection of regime performance (Armingeon and Guthmann Citation2014; Quaranta and Martini Citation2016). One clear advantage with using survey data provided by Eurobarometer (EB) is that it allows for both a cross-national and a longitudinal perspective in terms of regime support across the CEE region, and EB has gathered country-specific survey data across this region from 2004. It thus constitutes the obvious data source for this kind of research approach (Hobolt and de Vries Citation2016, 416–417).Footnote1

The main independent variable of interest for this research purpose is country year-specific levels of democratic performance. It is, however, a well-established assumption that “measuring democracy is not an easy task” (Bühlmann et al. Citation2012, 519). The basis of all comparative measurements of democratic performance centres on distinguishing high-quality democracies from low-quality ones (Diamond and Morlino Citation2004). Although, as previously suggested, internal processes of democratic backsliding can occur in various forms and are not always easily observable (Jee, Lueders, and Myrick Citation2019). According to Diamond and Morlino (Citation2004, 22), a “good democracy” at least includes stable political institutions, political equality and free elections, but as they further suggested, “there is no objective way of deriving a single framework of democratic quality, right and true for all societies”. Hence, no single measurement of democratic performance is able to account for all the essential elements of what constitutes a high- or low-quality democracy, as many simultaneous processes of democratic backsliding are occurring simultaneously. Consequently, it is necessary to include a number of measurements to account for various types of democratic performances in order to identify broader patterns.

Based on country-expert assessments, the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) dataset distinguishes between a number of high-level principles of democracy, and from those distinctions a number of different democracy indices, measuring to what extent a specific democracy related ideal is achieved, are created (Coppedge et al. Citation2020). All of these indices run on a continuous scale from 0 to 1, with a higher value indicating a higher level of democracy quality. The V-Dem dataset is now widely used by scholars for similar purposes (Claassen Citation2020; Mechkova, Lührmann, and Lindberg Citation2017; Stanley Citation2019). Hence, in order to account for various aspects of democratic performance, two indicators of democratic performance, drawn from version 10 of V-Dem, are utilised in this study. The first indicator is the Electoral Democracy Index (EDI), which measures to what extent the ideal of an electoral democracy, based on Dahl’s (Citation1971) classic guidelines, is being achieved within a country. This measurement thereby reflects the quality of free elections, universal suffrage, freedom of association and expression across countries (Teorell et al. Citation2018). The second indicator, the Liberal Democracy Index (LDI), measures the quality of democracy by the limits placed on government, such as the quality of the rule of law, the independence of the judiciary and the effectiveness of institutional checks and balances. Even if the LDI also takes the level of electoral democracy into account, the index mainly captures a different perspective of democratic performance related to the more liberal form of democracy that is promoted by the EU (Claassen Citation2019, 121–122; Coppedge et al. Citation2020).Footnote2 As it is necessary to further control for data source, the Freedom House Index, measuring the extent of civil liberties and political rights across countries, is also included in the model as a robustness test (Högström Citation2013).Footnote3 For a similar research purpose, the Democracy Barometer might have also been used (Bühlmann et al. Citation2012), but as the dataset available did not include data post 2017 it was not possible here.

In order to control for the most notorious country-level predictors of regime support used by scholars, two categories related to the economic and institutional performance of the countries, consisting of two determinants each, are further included in the model. Considering the economic performance of countries, country-specific annual unemployment rates reflect the short-term economic performances, and varying levels of unemployment are therefore expected to affect regime support over time, with higher levels of unemployment expected to contribute to declining levels of regime support (Quaranta and Martini Citation2016). In order to control also for the difference between richer and poorer CEE countries, a variable for GDP per capita, is also included in the model as an indicator of the socioeconomic development across the region (Claassen Citation2020; Magalhaes Citation2014).Footnote4 Eurostat provided annual data on economic performance, as the data enables comparisons across the CEE region over time.

Considering the institutional performance and institutional quality, the model will further account for country-level variations in non-corruption and income inequality. For this purpose, data derived from the Corruption Perception Index (CPI), provided by Transparency International, is included in the model (Anderson and Tverdova Citation2003; Claassen Citation2020; Van der Meer and Dekker Citation2011; Van Erkel and Van der Meer Citation2016). The index ranks countries in terms of the pervasiveness of corruption, with the estimates derived from expert assessments and opinion surveys.Footnote5 It should, however, be noted that this index has been widely criticised. Still, limited to the context of the CEE region it can be considered as a valid measurement of country-level corruption levels (Charron Citation2016). The country levels of economic inequality are measured by the Gini Index derived from Eurostat data, which is widely used to measure and compare the levels of income inequality across countries.Footnote6

Analysis

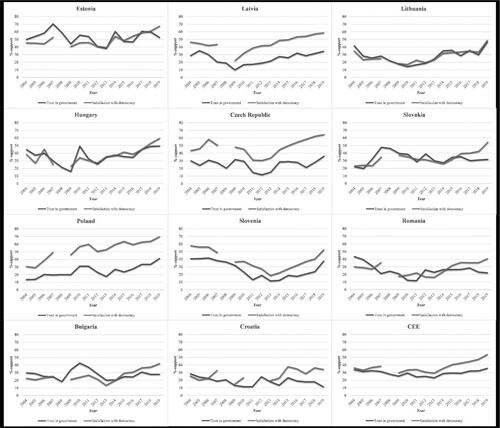

To begin with, an overview of country-level trends in regime support across the CEE region 2004–2019 is presented below in , based on both measurements of regime support.

Figure 1. Regime support across CEE countries, country-level mean values 2004–2019. Sources: Standard Eurobarometer survey data Citation2004–Citation2019. Notes: Data for “satisfaction with democracy” 2008 is missing, as the survey item was not included by EB in any of the two Standard EB surveys 2008. For comparative purposes, mean values of regime support across the CEE (N = 11) is also included in the figure.

Looking at this period, regime support seemingly peaked across the CEE region in 2019, both in terms of trust in government and democratic satisfaction. Narrowing down to only a ten-year period from 2009 to 2019, the mean levels of trust in government have increased with over ten percentage points, while the mean levels of democratic satisfaction have increased with over 24 percentage points, across the CEE region. Especially Hungary stands out during this period; with levels of democratic satisfaction increasing with 36.5 percentage points and trust in government increasing with 33.5 percentage points. This after ten-years of continuous Fidesz-rule. Continuing with the other two backsliding democracies (Stanley Citation2019), the levels of democratic satisfaction increased with 16.3 percentage points in Czech Republic and with 23.9 percentage points in Poland, while trust in government increased with 4.3 percentage points in Czech Republic and with 21.3 percentage points in Poland between 2009 and 2019. By scrutinising the country-specific trends, it becomes evident that regime support tends to fluctuate over time across the region. Furthermore, as becomes clear when looking at the overall trend during this period, the country levels of regime support have increased significantly during this period, and this especially since 2013. This is a surge possibly connected to the end of the Eurocrisis (Cordero and Simón Citation2016). Furthermore, within-country developments in regards to both indicators of regime support broadly follows the same patterns, even though there are some minor exceptions. At least in terms of the three backsliding democracies, there initially seems to be a negative relationship between democratic performance and regime support over time. This assumption is further supported by the results from a bivariate correlation analysis, presented in .

Table 1. Regime support and democracy development correlation, 2004–2019.

In the next step of the analysis, and following Söderlund, Wass, and Grofman (Citation2011, 100–101), the results from the LMM analysis are presented. Hereafter the country based regime performance measurements are modelled as a combination of (1) their mean values across time for each Member State and (2) year specific values for each Member State and measurement of public support (the variable is therefore cluster-mean centred, i.e. the deviation from the Member State mean). LMMs allow the model to consider both time-invariant (mean) and time-varying (year-specific) covariates as predictors of a continuous dependent variable. In the model, the mean values account for the between countries variability, and the measurement-specific values account for the within countries variability (or the regime support measurement-specific deviation from the cluster mean). The rationale for including the cluster mean as a separate covariate is in order to more directly assess whether the between and within countries effects differ, which is necessary for this research purpose (see Appendix for descriptive data on the variables included in the model). The main results from the analyses are presented below in , including values reflecting the regression estimates, standard errors, variance components and the explained variance, following Lahuis et al. (Citation2014), achieved by the multilevel models.

Table 2. Predicting varying country levels of regime support 2004–2019.Table Footnotea

The findings presented suggest that regime performance clearly predicts regime support, which is in line with the literature. Still, not all types of regime performances affect regime support and the type of regime performance that matters does not matter equally for the two kinds of regime support. Thus, it is evident that these two measurements of regime support neither are measuring the same thing nor are they equally affected by regime performance across the CEE region. Furthermore, both the economic and institutional performances indicators turned out to be statistically significant determinants for the within and between countries variations in regime support. In terms of the statistical effects, the within-country effects were stronger in relation to democratic satisfaction than trust in government, and the variance explained within countries were also higher.

Discussion

The findings suggest that higher levels of democratic performance predicts higher levels of regime support between countries, which is in line with the findings from earlier studies (Christmann Citation2018; Magalhaes Citation2014). On the other hand, declining levels of democratic performance were related to higher levels of regime support over time. Looking at the country-specific correlations between democratic performance and regime support, the connection becomes even clearer, with the correlations in Hungary, Poland, Lithuania and Slovenia being statistically significant for both types of regime support. As better democratic performance was expected to contribute to higher levels of support for democracy as a system of governance among democracies (Magalhaes Citation2014), these findings suggest that there is instead a reversed relation in terms of regime support across the CEE region. Thus, the assumption that regime support should increase the more democratic a regime becomes is not supported by these findings. Nevertheless, as the findings are based solely on a sample of eleven countries covering a 15-year period the connection is in need of more scrutiny in order to make broader generalisations. Still, as the connection remains statistically significant for each measurement of democratic performance, and even after controlling for the most widely used explanatory indicators, the findings seem initially robust for the explicit context of the post-communist Member States of the EU.

Moreover, by controlling for a number of contextual-level determinants in the statistical model it was possible to confirm a number of macro-level connections between regime performance and regime support, such as the impact of economic and institutional performance on regime support. Nonetheless, this type of macro-level study just scratches the surface of a complex issue, and hence this study only functions as an introduction to deeper, and more statistically advanced, analyses. Still, the findings presented in this study shows that the democratic performance of countries affects the regime evaluations within new and transitional democracies. Hence, macro-level studies focusing on explaining country-level variations in regime support should also start controlling for the democratic performance of countries. Future studies should try to study this connection also at the individual level, possibly identifying the characteristics of those individuals expressing higher levels of regime support across this region.

Conclusions

This article has addressed the development between democratic performance and regime support across the CEE region during the period between 2004 and 2019 in order to identify patterns of similarities. Even though the strengthening and safeguarding of liberal democracy is an outspoken goal of the EU (Börzel and Schimmelfennig Citation2017, 291), liberal democracy is clearly eroding across the CEE region (Dawson and Hanley Citation2016, 2). According to Keleman (Citation2020, 494), the EU is now even in a situation referred to as authoritarian equilibrium, suggesting that the EU is “now providing a hospitable environment for aspiring autocrats”. Following the guidelines from the system support theory (Easton Citation1965, 1975), longer periods of high levels of specific support should transform into the more diffuse kind of support for the system of governance, no matter if the system is liberal, illiberal or authoritarian. Thus, as long as the governments are improving the everyday living conditions the public might be willing to accept a stepwise dismantling of liberal democracy in favour of, for instance, a more illiberal type of democracy. At least in the short-run. However, it will become increasingly difficult for the public to reverse course once an illiberal democracy has been firmly established within any type of national setting. Given that high levels of regime support remain crucial for the survival of democracies and non- democracies alike (Claassen Citation2019; Easton Citation1965), the connection between regime support and democratic performance across the CEE region does not offer any comfort for European liberals. Hence, for the future of liberal democracy across the EU, and for the future of the EU in general (Sitter and Bakke Citation2019, 15), there are apparent reasons to worry about this development.

Even as the ongoing “populist and anti-liberal wave” (Bugarič and Ginsburg Citation2016, 1) have affected most parts of Europe, the country-specific effects differ. Thus, even though a lot of the political and scholarly focus have been on the developments across the CEE region, there are also reasons to look closer at the political developments in a number of West European countries, as it is impossible to “be certain that any democracy – no matter how long-standing – is consolidated” (Claassen Citation2020, 51). Furthermore, according to Wodak (Citation2019, 208), a process of “shameless normalization” has also been occurring within established Western democracies such as Austria, the UK, Italy and the Netherlands. As Claassen (Citation2020) has shown, public support for democracy can also start to decline within established democracies, which is in line with Lipset’s (Citation1959, 89) argument that “even in legitimate systems, a breakdown of effectiveness, repeatedly or for a long period, will endanger its stability”. Therefore, the main conclusion derived from this study is that the increasing levels of regime support combined with democratic backsliding in a growing number of countries across the CEE region might even start constitutes a key challenge for the future of liberal democracy in the EU. Thus, these findings add support to Rupnik’s (Citation2007, 22) warning that these countries might over time start to undermine the EU from within.

Economic breakdowns have been shown to contribute to democratic recessions (Bernhard, Reenock, and Nordstrom Citation2003), and in this sense the fallouts of the Global Recession and the Eurocrisis might have just accelerated an inevitable process. Since the start of the Global Recession, populist radical right parties with illiberal political programmes have entered government in Poland, Hungary, Bulgaria, Slovakia, Czech Republic and Estonia (Bochsler and Juon Citation2020). Once they are in a governing position, these parties have also been shown to start undermining the liberal form of democracy in their respective countries (Huber and Schimpf Citation2016). Hence, a growing number of scholars have started to argue that the CEE region is now simply experiencing a reversed wave of democratisation (Bochsler and Juon Citation2020; Diamond Citation2015). This development could further start to accelerate after the fallouts of the COVID-19 pandemic are being felt across the CEE region. It is not farfetched to expect that the outcome of the pandemic will contribute to spikes in nationalism, declining levels of economic growth and the further weakening of the EÚs possibilities of affecting national level political developments. The findings presented in this study suggests that the public across CEE countries are at least not being bothered with democratic backsliding, and might even welcome it, as long as other types of societal elements are improving.

From a broader perspective, the evidence provided by this study further suggest that the previously established assumption concerning the relation between democratic consolidation and democratic perseverance is not necessarily true. It has been suggested that there should be little risk of democratic backsliding once a country reaches the status of consolidated democracy (Linz and Stepan Citation1996), an assumption based on a notion that at such stage of democratic development the democratic system should be able to sustain itself by effective self-control by the public (Bernhard Citation2020). Democratic performance across the CEE region peaked between 2011 and 2012, according to the LDI, when seven of the countries reached the regime status as liberal democracies but in 2019 only Estonia, Latvia and Slovenia remained at that level (Lührmann et al. Citation2020). Hence, scholars might have misjudged the desire of the public to exercise effective self-control for the safeguarding of a more liberal democratic regime type. The findings from this study moreover suggest that the public is willing to continue supporting a regime even after it enters a transition period towards a less liberal form. Notwithstanding that, most Europeans still prefer democracy to other forms of governance but a development towards a less liberal form of governance does not seem to be a deal breaker in terms of continuing regime support, at least not as long as other regime elements are seemingly improving. Reaching the regime status of a consolidated liberal democracy, in addition to being an EU Member State, is thus clearly no guarantee for the perseverance of the liberal form of democratic governance in Europe. Hence, scholars should be careful not to overestimate the importance that the public actually puts on living in a liberal form of democratic regime.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (283 KB)Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers and the participants during the CERGU research seminar in Gothenburg, Sweden, in April 2020 for insightful comments on earlier versions of the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Thomas Karv

Thomas Karv is a postdoctoral researcher at the Social Science Research Institute at Åbo Akademi University, Finland. He has been a visiting researcher during 2020 at the Centre for European Research at the University of Gothenburg (CERGU), Sweden. His research is focused on public opinion, European integration and system support theories. His most research publication is a monograph titled: Public Attitudes Towards the European Union: A Study Explaining the Variations in Public Support Towards the European Union Within and Between Countries Over Time (2019).

Notes

1 The Standard EB surveys are collected twice a year (spring and fall), and since the fall of 2004 (EB 62), all of the CEE countries included in the empirical part of this study are regularly included in the survey. Moreover, in order to create comparable country-year values, a mean value based on the spring and fall editions is created for each country-year (Christmann Citation2018). Hence, original survey data from, altogether, 30 different surveys is utilised in this study. Country-year specific values for “Trust in the national government” are created from using the EB survey question: “I would like to ask you a question of how much trust you have in certain institutions. For each of the following institutions, please tell me if you tend to trust it or tend not to trust it?” Percentage points in is showing country-year mean values answering “Tend to trust”, with “Dońt know” answers excluded. Country-year specific values for “Satisfaction with national democracy” are created from using the EB survey question: “On the whole, are you very satisfied, fairly satisfied, not very satisfied or not at all satisfied with the way democracy works in (OUR COUNTRY)?” Percentage points in showing country-year mean values answering either “Very satisfied” or “Fairly satisfied”, with “Dońt know” answers excluded.

2 The scale for the EDI and LDI indices have been adjusted from 0–1 to 0–100. Hence, an original value of 0.11 is 11 in the dataset.

3 The Freedom in the World values used here are based on the aggregated values for all categories combined, ranging from 0 to 100, with a value of 100 indicating full freedom. These values are hence more generalisable than the V-Dem measurements, which differ between different elements of democracy. However, the Freedom House measurements that are based on expert assessments have also been blamed to be biased in favour of allies of the USA (Steiner Citation2016).

4 The values for GDP per capita are in PPS (purchasing power parity) and calculated in relation to the EU28 average, set to equal 100. If a country’s average is higher than 100, the country’s average per head is higher than the EU average.

5 The Corruption Perceptions index ranges from 0 to 100, with higher values indicating lower levels of corruption.

6 The Gini Index measures the wealth distribution of a country’s population, ranging from 0 to 100, with a lower value indicating lower levels of income inequality.

References

- Anderson, Christopher J., and Yuliya V. Tverdova. 2003. “Corruption, Political Allegiances, and Attitudes Toward Government in Contemporary Democracies.” American Journal of Political Science 47 (1): 91–109. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-5907.00007.

- Armingeon, Klaus, and Kai Guthmann. 2014. “Democracy in Crisis? The Declining Support for National Democracy in European Countries, 2007–2011.” European Journal of Political Research 53 (3): 423–442. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12046.

- Batory, Agnes. 2018. “Corruption in East Central Europe: has EU Membership Helped?” In Handbook on the Geographies of Corruption, edited by Barney Warf, 169–182. Cheltenham, UK & Northampton, MA, USA: Edward Elgar.

- Bermeo, Nancy. 2016. “On Democratic Backsliding.” Journal of Democracy 27 (1): 5–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2016.0012.

- Bernhard, Michael. 2020. “What Do We Know about Civil Society and Regime Change Thirty Years After 1989?” East European Politics 36 (3): 341–362. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21599165.2020.1787160.

- Bernhard, Michael, Christopher Reenock, and Timothy Nordstrom. 2003. “Economic Performance and Survival in New Democracies: Is There a Honeymoon Effect?” Comparative Political Studies 36 (4): 404–431. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414003251175.

- Bliese, Paul, David Chan, and Robert Ployhart. 2007. “Multilevel Methods: Future Directions in Measurement, Longitudinal Analyses, and Nonnormal Outcomes.” Organizational Research Methods 10 (4): 551–563. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428107301102.

- Bochsler, Daniel, and Andreas Juon. 2020. “Authoritarian Footprins in Central and Eastern Europe.” East European Politics 36 (2): 167–187. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21599165.2019.1698420.

- Börzel, Tanja, and Julia Langbein. 2019. “Core-Periphery Disparities in Europe: Is There a Link Between Political and Economic Divergence?” West European Politics 42 (5): 941–964. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2018.1558534.

- Börzel, Tanja, and Frank Schimmelfennig. 2017. “Coming Together or Drifting Apart? The EÚs Political Integration Capacity in Eastern Europe.” Journal of European Public Policy 24 (2): 278–296. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016.1265574.

- Brusis, Martin. 2016. “Democracies Adrift: How the European Crises Affect East-Central Europe?” Problems of Post-Communism 63 (5–6): 263–276. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10758216.2016.1201772.

- Bugarič, Bojan, and Tom Ginsburg. 2016. “The Assault on Postcommunist Courts.” Journal of Democracy 27 (3): 69–82. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2016.0047.

- Bühlmann, Marc, Wolfgang Merkel, Lisa Müller, and Bernhard Wessels. 2012. “The Democracy Barometer: A New Instrument to Measure the Quality of Democracy and its Potential for Comparative Research.” European Political Science 11: 519–536. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/eps.2011.46.

- Chang, Alex, Yun-han Chu, and Bridget Welsh. 2013. “Southeast Asia: Sources of Regime Support.” Journal of Democracy 24 (2): 150–164. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2013.0025.

- Charron, Nicholas. 2016. “Do Corruption Measures Have a Perception Problem? Assessing the Relationship Between Experiences and Perceptions of Corruption among Citizens and Experts.” European Political Science Review 8 (1): 147–171. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773914000447.

- Christensen, Tom, and Per Laegreid. 2005. “Trust in Government: The Relative Importance of Service Satisfaction, Political Factors, and Demography.” Public Performance & Management Review 28 (4): 487–511. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2005.11051848.

- Christmann, Pablo. 2018. “Economic Performance, Quality of Democracy and Satisfaction with Democracy.” Electoral Studies 53: 79–89. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2018.04.004.

- Cianetti, Licia, James Dawson, and Seán Hanley. 2018. “Rethinking “Democratic Backsliding” in Central and Eastern Europe – Looking Beyond Hungary and Poland.” East European Politics 34 (3): 243–256. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21599165.2018.1491401.

- Cirtautas, Arista M., and Frank Schimmelfennig. 2010. “Europeanisation Before and After Accession: Conditionality, Legacies and Compliance.” Europe-Asia Studies 62 (3): 421–441. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09668131003647812.

- Claassen, Christopher. 2019. “Does Public Support Help Democracy Survive?” American Journal of Political Science 64 (1): 118–134. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12452.

- Claassen, Christopher. 2020. “In the Mood for Democracy? Democratic Support as Thermostatic Opinion.” American Political Science Review 114 (1): 36–53. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055419000558.

- Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, David Altman, Michael Bernhard, et al. 2020. “V-Dem Dataset v10” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.23696/vdemds20.

- Cordero, Guillermo, and Pablo Simón. 2016. “Economic Crisis and Support for Democracy in Europe.” West European Politics 39 (2): 305–325. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2015.1075767.

- Dahl, Robert. 1971. Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Dalton, Russell. 2014. Citizen Politics: Public Opinion and Political Parties in Advanced Industrial Democracies. 6th ed. London, UK: SAGE Publications.

- Dawson, James, and Seán Hanley. 2016. “What’s Wrong with East-Central Europe?: The Fading Mirage of the ‘Liberal Consensus’.” Journal of Democracy 27 (1): 20–34. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2016.0015.

- Diamond, Larry. 2015. “Facing Up to the Democratic Recession.” Journal of Democracy 26 (1): 141–155. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2015.0009.

- Diamond, Larry, and Leonardo Morlino. 2004. “The Quality of Democracy: An Overview.” Journal of Democracy 15 (4): 20–31. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2004.0060.

- Easton, David. 1965. A System Analysis of Political Life. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago press.

- Easton, David. 1975. “A Re-Assessment of the Concept of Political Support.” British Journal of Political Science 5 (4): 435–457. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123400008309.

- Edwards, Lloyd. 2000. “Modern Statistical Techniques for the Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Biomedical Research.” Pediatric Pulmonology 30 (4): 330–344. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-0496(200010)30:4<330::AID-PPUL10>3.0.CO;2-D.

- Eurobarometer. 2004–2019. “European Commission and European Parliament, Brussels.” Standard Eurobarometer Surveys 62.0 (2004)–91.5 (2019). TNS Opinion & Social. GESIS Data Archive, Cologne.

- Fairbrother, Malcolm. 2014. “Two Multilevel Modelling Techniques for Analysing Comparative Longitudinal Survey Datasets.” Political Science Research and Methods 2 (1): 119–140. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2013.24.

- Fairbrother, Malcolm, and Isaac W. Martin. 2013. “Does Inequality Erode Social Trust? Results from Multilevel Models of US States and Counties.” Social Science Research 42 (2): 347–360. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2012.09.008.

- Hakhverdian, Armen, and Quinton Mayne. 2012. “Institutional Trust, Education, and Corruption: A Micro-Macro Interactive Approach.” The Journal of Politics 74 (3): 739–750. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381612000412.

- Hanley, Sean, and Milada Vachudova. 2018. “Understanding the Illiberal Turn: Democratic Backsliding in the Czech Republic.” East European Politics 34 (3): 276–296. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21599165.2018.1493457.

- Hobolt, Sara, and Catherine E. de Vries. 2016. “Public Support for European Integration.” Annual Review of Political Science 19: 413–432. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-042214-044157.

- Högström, John. 2013. “Does the Choice of Democracy Measure Matter? Comparisons Between the Two Leading Democracy Indices, Freedom House and Polity IV.” Government and Opposition 48 (2): 201–221. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2012.10.

- Huber, Robert, and Christian Schimpf. 2016. “The Influence of Populist Radical Right Parties on Democratic Quality.” Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft 10: 103–129. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12286-016-0302-0.

- Jee, Haemin, Hans Lueders, and Rachel Myrick. 2019. “Towards a Unified Concept of Democratic Backsliding.” Working Paper, Stanford University. doi:https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3374080.

- Karv, Thomas. 2019. Public Attitudes Towards the European Union – A Study Explaining the Variations in Public Support Towards the European Union Within and Between Countries Over Time. Turku: Åbo Akademi University Publications. https://www.doria.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/170812/karv_thomas.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Keleman, Daniel. 2020. “The European Union’s Authoritarian Equilibrium.” Journal of European Public Policy 27 (3): 481–499. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1712455.

- Kim, Soonhee. 2010. “Public Trust in Government in Japan and South Korea: Does the Rise of Critical Citizens Matter?” Public Administration Review 70 (5): 801–810. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2010.02207.x.

- Klingemann, Hans-Dieter. 1999. “Mapping Political Support in the 1990s: A Global Analysis.” In Critical Citizens: Global Support for Democratic Governance, edited by Pippa Norris, 31–56. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Krastev, Ivan. 2007. “Is East-Central Europe Backsliding? The Strange Death of the Liberal Consensus.” Journal of Democracy 18 (4): 56–64. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/223236.

- Krieckhaus, Jonathan, Byunghwan Son, Nisha Bellinger, and Jason Wells. 2013. “Economic Inequality and Democratic Support.” The Journal of Politics 76 (1): 139–151. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381613001229.

- Lahuis, David M., J. Hartman Michael, Shotaro Hakoyama, and Patrick C. Clark. 2014. “Explained Variance Measures for Multilevel Models.” Organizational Research Methods 17 (4): 433–451. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428114541701.

- Linde, Jonas. 2012. “Why Feed the Hand That Bites You? Perceptions of Procedural Fairness and System Support in Post-Communist Democracies.” European Journal of Political Research 51 (3): 410–434. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2011.02005.x.

- Linz, Juan J., and Alfred C. Stepan. 1996. “Toward Consolidated Democracies.” Journal of Democracy 7 (2): 14–33. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.1996.0031.

- Lipset, Seymour M. 1959. “”Some Social Requites of Democracy: Economic Development and Political Legitimacy.”.” American Political Science Review 53 (1): 69–105. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1951731.

- Lührmann, Anna, and Staffan I. Lindberg. 2019. “A Third Wave of Autocratization Is Here: What Is New About It?” Democratization 26 (7): 1095–1113. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2019.1582029.

- Lührmann, Anna, Seraphine F. Maerz, Sandra Grahn, Nazifa Alizada, Lisa Gastaldi, Sebastian Hellmeier, Garry Hindle, and Staffan I. Lindberg. 2020. Autocratization Surges – Resistance Grows. Democracy Report 2020. Varieties of Democracy Institute (V-Dem). https://www.v-dem.net/media/filer_public/51/43/51434648-2383-4569-84d0-e02fbd834b3e/v-dem_democracyreport2020_20-03-18_final_lowres.pdf.

- Magalhaes, Pedro C. 2014. “Government Effectiveness and Support for Democracy.” European Journal of Political Research 53 (1): 77–97. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12024.

- Matthes, Claudia-Yvette. 2016. “Comparative Assessments of the State of Democracy in East-Central Europe and its Anchoring in Society.” Problems of Post-Communism 63 (5–6): 323–334. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10758216.2016.1201771.

- Mechkova, Valeriya, Anna Lührmann, and Staffan I. Lindberg. 2017. “How Much Democratic Backsliding?” Journal of Democracy 28 (4): 162–169. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2017.0075.

- Miller, Arthur. 1974. “Political Issues and Trust in Government: 1964–1970.” American Political Science Review 68 (3): 951–972. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1959140.

- Mishler, William, and Richard Rose. 2001. “What Are the Origins of Political Trust? Testing Institutional and Cultural Theories in Post-Communist Societies.” Comparative Political Studies 34 (1): 30–62. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414001034001002.

- Mishler, William, and Richard Rose. 2002. “Learning and Re-Learning Regime Support: The Dynamics of Post-Communist Regimes.” European Journal of Political Research 41 (1): 5–36. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.00002.

- Mishler, William, and Richard Rose. 2005. “What Are the Political Consequences of Trust? A Test of Cultural and Institutional Theories in Russia.” Comparative Political Studies 38 (9): 1050–1078. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414005278419.

- Mungiu-Pippidi, Alina. 2007. “Is East-Central Europe Backsliding? EU Accession is No ‘End of History’.” Journal of Democracy 18 (4): 8–16. https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/223238.

- Norris, Pippa. 2011. Democratic Deficit: Critical Citizens Revisited. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Papadimitropoulou, Katerina, Stijnen Theo, Olaf M. Dekkers, and Saskia le Cessie. 2019. “One-Stage Random Effects Meta-Analysis Using Linear Mixed Models for Aggregate Continuous Outcome Data.” Research Synthesis Methods 10 (3): 360–375. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1331.

- Park, Chong-Min. 1991. “Authoritarian Rule in South Korea: Political Support and Governmental Performance.” Asia Survey 31 (8): 743–761. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2645227.

- Quaranta, Mario, and Sergio Martini. 2016. “Does the Economy Really Matter for Satisfaction with Democracy? Longitudinal and Cross-Country Evidence from the European Union.” Electoral Studies 42: 164–174. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2016.02.015.

- Rose, Richard, and William Mishler. 2002. “Comparing Regime Support in Non-Democratic and Democratic Countries.” Democratization 9 (2): 1–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/714000253.

- Rupnik, Jacques. 2007. “Is East-Central Europe Backsliding? From Democracy Fatigue to Populist Backlash.” Journal of Democracy 18 (4): 17–25. https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/223242.

- Rupnik, Jacques, and Jan Zielonka. 2013. “Introduction: The State of Democracy 20 Years on: Domestic and External Factors.” East European Politics and Societies 27 (1): 3–25. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0888325412465110.

- Schleifer, Andrei, and Daniel Treisman. 2014. “Normal Countries: The East 25 Years After Communism.” Foreign Affairs 93 (6): 92–103. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24483924.

- Sedelmeier, Ulrich. 2014. “Anchoring Democracy from Above? The European Union and Democratic Backsliding in Hungary and Romania After Accession.” Journal of Common Market Studies 52 (1): 105–121. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12082.

- Sitter, Nick, and Elisabeth Bakke. 2019. “Democratic Backsliding in the European Union.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.1476.

- Snijders, Tom. 1996. “Analysis of Longitudinal Data Using the Hierarchical Linear Model.” Quality & Quantity 30: 405–426. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00170145.

- Solt, Frederick. 2012. “The Social Origins of Authoritarianism.” Political Research Quarterly 65 (4): 703–713. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912911424287.

- Söderlund, Peter, Hanna Wass, and Bernard Grofman. 2011. “The Effect of Institutional and Party System Factors on Turnout in Finnish Parliamentary Elections, 1962–2007: A District Level Analysis.” Essays in Honor of Hannu Nurmi Homo Oeconomicus 28 (1–2): 91–109.

- Stanley, Ben. 2019. “Backsliding Away? The Quality of Democracy in Central and Eastern Europe.” Journal of Contemporary European Research 15 (4): 343–353. doi:https://doi.org/10.30950/jcer.v15i4.1122.

- Steiner, Nils. 2016. “Comparing Freedom House Democracy Scores to Alternative Indices and Testing for Political Bias: Are US Allies Rated as More Democratic by Freedom House?” Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice 18 (4): 329–349. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13876988.2013.877676.

- Teorell, Jan, Michael Coppedge, Staffan I. Lindberg, and Svend-Erik Skaaning. 2018. “Measuring Polyarchy Across the Globe, 1900–2017.” Studies in Comparative International Development 54: 71–95. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-018-9268-z.

- Uitz, Renata. 2015. “Can You Tell When an Illiberal Democracy Is In the Making? An Appeal to Comparative Constitutional Scholarship from Hungary.” International Journal of Constitutional Law 13 (1): 279–300. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/icon/mov012.

- Van der Meer, Tom, and Armen Hakhverdian. 2017. “Political Trust as the Evaluation of Processes and Performance: A Cross-National Study of 42 European Countries.” Political Studies 65 (1): 81–102. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321715607514.

- Van der Meer, Tom, and Paul Dekker. 2011. “Trustworthy States, Trusting Citizens? A Multi-Level Study Into Objective and Subjective Determinants of Political Trust.” In Political Trust: Why Context Matters, edited by Sonja, Zmerli, and Marc Hooghe, 95–116. Colchester: ECPR Press.

- Van Erkel, Patrick, and Tom Van der Meer. 2016. “Macroeconomic Performance, Political Trust and the Great Recession: A Multilevel Analysis of the Effects of Within-Country Fluctuations in Macroeconomic Performance on Political Trust in 15 EU Countries, 1999–2011.” European Journal of Political Research 55 (1): 177–197. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12115.

- Wagner, Alexander F., Friedrich Schneider, and Martin Halla. 2009. “The Quality of Institutions and Satisfaction with Democracy in Western Europe – A Panel Analysis.” European Journal of Political Economy 25 (1): 30–41. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2008.08.001.

- Waldron-Moore, Pamela. 1999. “Eastern Europe at the Crossroads of Democratic Transition: Evaluating Support for Democratic Institutions, Satisfaction with Democratic Government, and Consolidation of Democratic Regimes.” Comparative Political Studies 32 (1): 32–62. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414099032001002.

- Weatherford, Stephen. 1987. “How Does Government Performance Influence Political Support?” Political Behavior 9: 5–28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00987276.

- Welzel, Christian. 2007. “Are Levels of Democracy Affected by Mass Attitudes? Testing Attainment and Sustainment Effects on Democracy.” International Political Science Review 28 (4): 397–424. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512107079640.

- Wodak, Ruth. 2019. “Entering the ‘Post-Shame Era’: The Rise of Illiberal Democracy, Populism and Neo-Authoritarianism in Europe.” Global Discourse 9 (1): 195–213. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1332/204378919X15470487645420.

Appendices

Figure A1. Democratic performance across CEE countries (adjusted scales), country-level values 2004–2019.Sources: V-Dem and Freedom House.Notes: The V-Dem scales have been adjusted for the empirical purpose in the statistical analyses. Hence, a V-Dem value of for instance 0.11 has been changed to 11.

Table A1. Descriptive statistics of the variables used in the statistical model.