ABSTRACT

The changes in the global neoliberal order leading up to the 2008 financial crisis shaped individual countries’ political–administrative transformations. One of the most important trends in politics since then has been the (re)centralization of scalar politics. Urban financialization, which was proposed as a solution for the economic contraction in the post-crisis era, required fast and centralized decision-making without leaving much room for citizen participation and local variation. Turkey is a case in point for this global trend. Amid such rapid urban growth, we identify two parallel processes that weaken the local institutions and localized development in Turkey: the shifting of decision-making powers from municipalities to central state organs, especially with regard to the real estate industry; and the shifting of decision-making powers from the elected members of the city councils to the mayors themselves. We attempt to demonstrate the (re)centralization of urban decision-making process in Turkey by looking at the decisions and the processes within which those decisions were taken at Ankara Metropolitan Municipality City Council between 2014 and 2016. We argue that the rise of neoliberal authoritarianism is reinforced by the centralization of urban decision-making processes.

INTRODUCTION

The changes in the global neoliberal order leading up to the 2008 financial crisis shaped individual countries’ political–administrative transformations. One of the most important trends in politics since then has been the (re)centralization of scalar politics. Urban financialization, which was proposed as a solution for the economic contraction in the post-crisis era, required fast and centralized decision-making without leaving much room for citizen participation and local variation. Turkey is a case in point for this global trend. Turkey has experienced accelerated urban growth of approximately 50% between the 1950s and the 2010s due to the central regulation of urban development. In 1950, 24.8% of the population lived in urban areas, while this had risen to 74.1% by 2016 (World Urbanization Prospects, Citation2018). As the urban growth rate slowed down in the second half of the 20th century, Turkish cities witnessed multiple waves of urban redevelopment. In the neoliberal era, slum gentrification and public housing projects took a financial turn (Yeşilbağ, Citation2019).

Amidst such rapid urban redevelopment, we identify two parallel processes that weaken the local institutions and localized development in Turkey: the shifting of decision-making powers from municipalities to central state organs, especially with regard to real estate industry; and the shifting of decision-making powers from the elected members of the city councils to the mayors themselves. The existing literature demonstrates the continuity in AKP’s policy of granting limited fiscal and administrative autonomy but not a political one (Savaşkan, Citation2020). Such partial autonomy was established through central state organs such as the Housing Development Administration of Turkey (TOKİ) and the Ministry of Environment and Urbanization (Tansel, Citation2019). This research focuses on the institutional changes at the local level that happened after a new municipality law was passed in 2012 (article 5216 for the former and article 6360 for the latter). The limitation imposed on the decision-making powers of the municipalities is discussed in the literature at length (Arıkboğa, Citation2015; Erder et al., Citation2016; Gül & Batman, Citation2013; Kayasü & Yetişkul, Citation2014); however, the limitations imposed on the decision-making powers of the elected members of the city councils have not received the same attention. We attempt to demonstrate the (re)centralization of urban decision-making processes in Turkey by looking at the decisions and the processes within which those decisions were taken at the Ankara Metropolitan Municipality City Council between 2014 and 2016. We start our case study in 2012 in order to include the administrative changes that accompanied Article 5216 and Article 6360. We specifically focused on the city council decisions in the period between 2014 and 2016 because the administrative transformations were implemented after the 2014 local elections. Therefore, 2012–16 is a period when it is possible to observe both the administrative and practical transformations in Ankara Metropolitan Municipality.

In this article, we argue that the rise of neoliberal authoritarianism is reinforced by the centralization of urban decision-making processes. Neoliberal authoritarianism has had important implications for local governance since 2012. A parallel development was a significant increase in decisions regarding real estate development. The centralization of local decision-making aimed to facilitate the financialization of urbanization. This article investigates the role of the formal institutions in the development of the post-crisis authoritarian urbanism and claims that the formal institutions originally designed to ensure representation and participation were instrumentalized for the centralization of urban decision-making. The decision-making powers were centralized in the hands of the mayors and specialized commissions, undermining the power and participation of the city council members in the general assembly.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. After this introduction, the literature on neoliberal rescaling and neoliberal authoritarianism will be critically examined to locate the Turkish case in a broader political economic context. The second section will introduce the local governance reforms in Turkey with respect to neoliberal authoritarian transition. It will introduce the regional variations in preparation for the third section, which will narrow down the focus to the case of Ankara. The fourth section will introduce and discuss the research findings. We use qualitative methods, drawing from semi-structured elite interviews conducted with city council members and activists in urban rights advocacy platforms in 2014 and 2015. The quantitative methods will include a collection of council decisions between 2014 and 2016 as well as national and provincial-level statistical data (MMGA Registers). The database used in this work is first compiled for the City Report (Kent Karnesi) citizen initiative, which worked towards producing accessible information about the activities of the mayor’s office in Ankara between 2013 and 2017.Footnote1 The main variable in our analysis is the recentralization of local governance. We examine it by comparing decisions taken by special commissions and the mayor, on the one hand, and by the city council general assembly, on the other. The explanatory tools are borrowed from the critical urban literature as seen fit, and the authoritarian neoliberal tendencies prevailing in Turkey, understood in terms of state rescaling through the 2008 economic crisis and the domestic political crisis of the 2010s. The state rescaling experienced after the 2012 Municipality Law consolidated crony relations by further rendering the city council unrepresentative and curtailing citizen involvement.

URBAN RECENTRALIZATION AND AUTHORITARIANISM

Territorial rescaling of the state facilitates capital accumulation, and in the neoliberal era, scaling down is seen as a common pattern (Brenner, Citation2004; Pinson & Journel, Citation2016). Administrative decentralization, that is, the shifting of the decision-making role of the state from the central to the local scale, is an integral part of neoliberal state rescaling. In the 1970s, a shift from managerial, Keynesian urban governance to entrepreneurial post-Keynesian neoliberal urban governance was observed (Brenner, Citation2004; Harvey, Citation1989). During the Keynesian governance period, state activity was nationally planned and substate units were administered by the central government. National-level policymaking is argued to have taken a major hit by the neoliberal turn, and to have been replaced by local, regional and supranational forms of governance (Jessop, Citation2000, Citation2002). This led to the rescaling of urban governance around cities, which became much more competitive and entrepreneurial in character (Brenner, Citation2004). It has been commonly argued that the primary motive behind this move towards decentralization was a desire to counter the ills of macroeconomic processes, such as deindustrialization, widespread unemployment, austerity measures and privatization (Harvey, Citation1989), as well as political, social and environmental problems (Jessop, Citation2002). Instead of relying on national institutions, Schumpeterian ‘post-national’ forces have increasingly come into play to find innovative solutions to these problems. The urban scale plays a major role in this process (Jessop, Citation2002). It is argued that because of the ‘declining powers of the nation state to control multinational money flows … ’, investment has increasingly been shaped by the ‘negotiation between international finance capital and local powers doing the best they can to maximize the attractiveness of the local site as a lure for capitalist development’ (Harvey, Citation1989, p. 5). Thus, cities have increasingly begun to take an ‘entrepreneurial stance to economic development’ (p. 4). However, the trend towards decentralization and entrepreneurialism has not taken place uniformly.

In advanced economies, administrative decentralization is often accompanied with fiscal decentralization. The fiscal autonomy of the local state arguably creates a realm of interest contestation for local actors, which in turn democratizes the local scale. In late industrializing economies and/or non-Western contexts, however, administrative and fiscal decentralization may be decoupled for a number of reasons (Cox, Citation2013; Park, Citation2013; Savaşkan, Citation2020). The variegated nature of state rescaling also shapes the recent recentralization trend.

According to the entrepreneurial city literature, neoliberal policies and the reduced administrative power of the central governments have caused local governments to use tools such as innovation and speculation as a response to the neoliberalization logic provided by the national state (Lauermann, Citation2018). A major space of the imposition of neoliberal logic is the entrepreneurial city. In narrow terms, ‘entrepreneurial city’ refers to the increased pro-business activities of local governments (Fuller, Citation2018). Urban actors increasingly engage in public–private partnerships to increase investments and economic growth via speculative construction of space (Harvey, Citation1989; Phelps & Miao, Citation2020). There are many factors that shape central–local relations, such as the political–administrative structure of individual cases and the transnational forces the local responds to. The literature on urban entrepreneurialism, however, focuses mostly on the economic processes such as speculation, risk-taking, inter-urban competition, branding, and pro-growth and pro-business policies in general (Fuller, Citation2018; Lauermann, Citation2014, Citation2018; Phelps & Miao, Citation2020).

Entrepreneurial activities and urban governance have largely been realized by mayors. It is argued that although some of the urban responsibilities are now mostly outsourced to private or quasi-private actors, this did not necessarily reduce the power of the mayors or the local government. On the contrary, in many cases in the aftermath of the transition to neoliberal, pro-growth urban governance, mayors have continued to be the leading actors (Ponzini & Rossi, Citation2010). They engaged in coalition building, real-estate speculation, increasingly used cities as ‘an outlet for neoliberal spatial policy … ’ and took part in public–private partnerships (Lauermann, Citation2014, Citation2018:, p. 209). However, focus on the increased power of mayors in local political decision-making processes and their intricate relationships with local business communities is mostly disregarded. The political processes that have accompanied rescaling, such as increased power of central governments on local governance, obstructed citizen participation in local politics, and reduced opportunities for democratic practices at the local level, are missing in the current literature. In the end, neoliberalism is instrumentalized by central governments, which provide a neoliberal framework upon which local governments act and therefore, central governments may still retain a role in shaping the local state, even if they are decidedly entrepreneurial.

There is evidence for continued central government involvement in local politics. As opposed to decentralization arguments, others argue that the nation-state has become more interventionist in urban governance/city-regionalism (Addie, Citation2013; Harrison, Citation2010; Jonas, Citation2013; Jonas & Moisio, Citation2018; Ward & Jonas, Citation2004). This is especially because the activities of the cities to attain economic development coincide with the interests of nation-states (Jonas, Citation2013; Jonas & Moisio, Citation2018), and because of the need for the city-regions to draw state power and resources when their comparative advantages are endangered by intensified inter-urban competition (Ward & Jonas, Citation2004). In other words, the proponents of the city-regionalism thesis argue that despite the common perception of downscaling, ‘the state seeks to reorganize its territorial structure in order to attract global investment and ensure the economic development of its most politically privileged urban centres’ (Jonas & Moisio, Citation2018, p. 356). The nation-state is viewed as both orchestrating city-regionalism ‘from above’ in the form of distribution, citizenship, identity, etc., and also materially supporting city regionalism through social and physical infrastructural investments (Jonas & Moisio, Citation2018; Ward & Jonas, Citation2004).

In addition to those scholars who look at the neoliberal entrepreneurial city and more state-involved city-regionalism, there is a strand of research that fuses both developmental and neoliberal aspects of urban governance. While mainly within the context of East Asian countries, this literature argues that urban development is realized mainly by the national state as this ‘developmental state (and its multi-scalar engagement with national and transnational interests) … ’ shaped urbanism (Shin, Citation2019, pp. 3–4). For instance, Shin and Kim (Citation2016) argue that first the developmental, then the neo-liberalizing Korean, state strongly influenced the process of urban redevelopment and gentrification in Seoul. This process was accompanied by silencing popular opposition via authoritarian measures. In contrast to the arguments for the neoliberal ‘roll-out’ states, it is argued that with the spread of urban capital accumulation tendencies promoted by neoliberalism, developmental states proactively engage in the construction of speculative built environments (Shin & Kim, Citation2016). In this case, the state does not retreat from urban governance during the neoliberal period. On the contrary, we observe a fusion of the interventionist developmentalist state often with authoritarian characteristics on the one hand, and the neoliberal urban governance framework that promotes urban capital accumulation on the other. In conclusion, this literature advocates that ‘state policies under neoliberalization contain elements of both “neoliberalism” and “developmentalism”’ (p. 556). The urban rescaling literature focuses on the issue mainly from an economic point of view, and while doing so it misses the political processes. Although it successfully explains the economic rationale behind the recent restructuring, it excludes the political explanations and processes which take place simultaneously.

Turkey in the AKP era is not a developmentalist state, but authoritarian tendencies born out of crony relations brings about an amalgamation of neoliberalism and recentralization of state–business relations, described in the literature on East Asian developmentalist states. Despite certain measures taken for decentralization and devolution of authority of local governments in the early 2000s, we argue that since the 1980s, and especially since the 2010s, there has been a strong tendency in Turkey towards recentralization (increased power of the central government, especially in terms of real estate-related issues, and increased prominence of mayors vis-à-vis elected city council members) in urban governance. In many cases, we see the reflections of neoliberal urban governance through public administration reform where municipalities were encouraged to become market actors to engage in public–private partnerships and privatization (Karaman, Citation2013), and the centralization of decision-making processes and top-down measures regarding urban redevelopment (Karaman, Citation2013; Karaman et al., Citation2020). Our focus is mainly on the latter trend as we investigate the decision-making processes in Ankara Metropolitan Municipality. We argue that, besides critical urban theories, neoliberal authoritarian tendencies provide a useful analytical tool to explain the recentralization of urban governance in Turkey.

The framework of neoliberal authoritarianism is relevant for conveying the Turkish case as it emphasizes the agency of the state in reproducing authoritarianism by centralizing decision-making via a combination of coercive, disciplinary and consensual forms, and dismisses a mere economic/market-centric definition of neoliberalism (Bilgiç, Citation2018; Kaygusuz, Citation2018; Özden et al., Citation2017; Tansel, Citation2018, Citation2019). With respect to the role of the state in reproducing authoritarianism, many authors have established Turkey as an example of neoliberal authoritarianism (Bedirhanoğlu, Citation2009; Bilgiç, Citation2018; Di Giovanni, Citation2017; Kaygusuz, Citation2018; Özden et al., Citation2017; Tansel, Citation2018, Citation2019).

The reflections of neoliberal authoritarianism on urban governance in Turkey have been well-documented. It is argued that neoliberal urban practices and authoritarian urban governance are intimately connected. Especially after the global financial crisis, urban governance witnessed increased state intervention and entrepreneurialism to promote economic growth (Tasan-Kok, Citation2015). Top-down interventionist practices in urban governance are adopted to reduce uncertainty, and to make faster decisions, which is realized by controlling the participatory mechanisms which might challenge and prolong the process (Di Giovanni, Citation2017). The centralization of local governance aims to eliminate dissenting voices in the representative institutions and accelerate decision-making processes in issue areas such as urban regeneration and sprawl (Bedirhanoğlu, Citation2019; Di Giovanni, Citation2017). Compliance with the investors’ demands is prioritized over the representativeness and transparency of decision-making processes. The elimination of elected bodies from decision-making processes is one of the factors constituting neoliberal authoritarianism (Clua-Losada & Ribera-Almandoz, Citation2017; Kaygusuz, Citation2018). Executive centralization has become a significant tool for the exercise of power of central government on key decision-making processes by curtailing democratic opposition. The state combined neoliberal programmes with authoritarian practices that relied on the recentralization of decision-making processes and closing of democratic avenues for challenging state policies (Tansel, Citation2019). The ‘strong’ state used both economic and political forms of intervention, control and restrictions in its urban governance. The centralization tendencies increased the decision-making powers of the central government especially with respect to redevelopment-related urban policies (Eraydin & Taşan-Kok, Citation2014).

Although authoritarian transformation was a continuous trend in the wider trajectory of neoliberalism even before the 2008 crisis, the financial crisis served as a significant stimulus to the anti-democratic tendencies of neoliberalism (Albo & Fanelli, Citation2014; Bruff, Citation2014; Bruff & Tansel, Citation2019; Kaygusuz, Citation2018; Peck, Citation2001). Similarly, the neoliberal era in Turkey is marked by political crises stemming from the lack of policy responsiveness. The mechanisms of seeking public consent through participation and supervision have been blocked at every level of the state in Turkey. Such blocking might be informal and hidden within the otherwise liberal institutions or through formal channels as the literature on planetary illiberalism suggests (Luger, Citation2020).

LOCAL GOVERNANCE REFORMS AND STATE RESCALING IN TURKEY

Existing studies use the demographic information of the city council members to demonstrate the relationship between the political and economic elite through networking studies. Some approached the issue from the perspective of service scale, subsidiarity, participation, democracy and local autonomy (Gül & Batman, Citation2013), while others focused on the legal, institutional and geographical changes in the structure of metropolitan municipalities (Arıkboğa, Citation2014). The problems the 2012 law exacerbated, such as lack of participation and democracy, service provision in rural areas, and centralization (Duru, Citation2013); and the evolution of urban policies, including the 2012 law, as a part of the neoliberal project and relations with the European Union (Kayasü & Yetişkul, Citation2014) are among the issues discussed in the literature. While those studies remain significant in exploring the transformations the 2012 law triggered, they lack a specific focus on the decision-making processes of city councils, which constitutes an indivisible part of local democracy.

Aside from these studies, there are also works that discuss the functioning of several individual metropolitan municipalities after the 2012 law. Those works mainly rely on a series of comprehensive semi-structured interviews conducted in 2014 by local researchers based in 10 metropolitan cities, namely Istanbul (Topal Demiroğlu & Okutan, Citation2015), İzmir (Aydoğan Ünal, Citation2015), Eskişehir (Suğur, Citation2015), Bursa (Çetinkaya, Citation2015), Gaziantep (Gültekin, Citation2015), Adana (Aksu Çam, Citation2015), Konya (Çukurçayır, Citation2015), Diyarbakır (Çiçek, Citation2015), Samsun (Mutlu, Citation2015) and Erzurum (Çolakoğlu, Citation2015). These researchers examined the inner workings of city councils and decision-making processes, the profiles of the council members, the workings of the commissions, the issues surrounding representation and participation, and the relationship between the council members and the other actors above the city scale (Arıkboğa, Citation2015). These studies concluded that the local governance reforms that took place after 2010 showed a clear tendency towards centralization, particularly regarding major decisions on macro-projects involving planning and construction (Erder et al., Citation2016).

After the 2012 law was promulgated, many services and decisions were centralized in the hands of the metropolitan city municipalities (Arıkboğa, Citation2014; Duru, Citation2013; Kandeğer & İzci, Citation2016). The main rationale for the passing of the 2012 law was to prevent coordination and planning problems among small units and contribute to economies of scale. However, the actual implementation of the law resulted in recentralization ‘around metropolitan municipalities’, which hindered ‘the democratic principles on which local governments used to be built upon’ (Akıllı & Akıllı, Citation2014, p. 683).

Studies that focused on the effects of Law No. 6360 (promulgated as a part of the 2012 law) on Ankara Metropolitan Municipality did so by explaining the centralization in decision-making processes on organizational and geographical grounds (Ceyhan & Tekkanat, Citation2018). While the former refers to the concentration of decision-making power in the hands of the highest authority in the city, the latter points to limited participation of local and provincial (taşra) governments in the decision-making process. The main claim is that while the new law would be a positive step in terms of increased autonomy from the central government, it would at the same time lead to centralization within the local governance (Ceyhan & Tekkanat, Citation2018). Although Ceyhan and Tekkanat (Citation2018) focus on the centralization of the decision-making process within Ankara Metropolitan Municipality, they do not provide a detailed analysis of the decisions made after the passing of the law.

Other studies on Ankara focused on specific issues after the implementation of the 2012 law. Tunçer and Ünal (Citation2016) introduce a case study on Kalecik, a district in greater Ankara; and Şahin (Citation2016) examines Ankara Metropolitan Municipality as a whole. Those studies dealt with the blurring of rural–urban differentiation with the new law, and concentrated on the organizational changes and spatial planning, problems encountered by the municipality personnel, citizens’ access to services (Şahin, Citation2016), and complaints issued against the municipality, as well as the impact of the law on agriculture, livestock and forestry (Tunçer & Ünal, Citation2016). These works ignore the centralization and decision-making processes in the Ankara Metropolitan Municipality’s City Council. Further studies focused on the district-level municipalities in 2011 and 2012, such as Çankaya and Keçiören local governments, and examined their ‘external environment, service provision, decision-making processes, use of technology and communications’ (Şahin et al., Citation2014, p. 160; Citation2015, p. 183).

Most of the studies that focus on the transformation of local governance either present a general picture without much empirical data or focus on municipalities other than Ankara (Aksu Çam, Citation2015; Arıkboğa, Citation2014; Aydoğan Ünal, Citation2015; Çetinkaya, Citation2015; Çiçek, Citation2015; Çolakoğlu, Citation2015; Çukurçayır, Citation2015; Gültekin, Citation2015; Mutlu, Citation2015; Suğur, Citation2015; Topal Demiroğlu & Okutan, Citation2015). This indicates a lack of understanding of one of the most contentious and clear examples of the effects of neoliberal authoritarianism on centralization in local government. Since the early years of the republic, Ankara has been a laboratory for urban policy innovation and experimentation, as these policy implementations later spread to the rest of the country from Ankara. Therefore, looking at the case of Ankara is essential to understand the evolution of urban development as well as the effects of more recent developments in Turkey (Keleş & Duru, Citation2008; Şahin, Citation2019).

FACTORS THAT SHAPE NEOLIBERAL AUTHORITARIANISM IN ANKARA

There are three reasons why Ankara is a case in point for urban neoliberal authoritarian transformation. First, it is the political capital of the country, and therefore the relationship between the political and economic elite in neoliberal authoritarianism is clearly demonstrated in the Ankara case. Second, the metropolitan municipality was in the hands of the same political party (Justice and Development Party, aka AKP) and the same mayor, Melih Gökçek, for 23 years. The AKP won control the central government three years after Gökçek’s tenure began. His tenure is one of the longest in Turkey despite his repeated policy failures (Batuman, Citation2013) and his openly anti-democratic rule (Balaban, Citation2004; Batuman, Citation2009). His tenure ended only when the central AKP government asked for his resignation in 2017. The interwoven networks of the AKP and Melih Gökçek in Ankara present a case for power consolidation in metropolitan municipalities as close ties with the central government are seen as crucial to the success of large-scale urban projects (Kuyucu, Citation2018).

Third, the impact of the 2012 law is clearly observable in Ankara since it was a metropolitan municipality before the law was promulgated. Due to its long history of being a metropolitan city and having a deep-rooted administrative structure, it is a case that lends itself to a comparison between the previous structure and the transformation that came with the 2012 law. This section will examine these three factors in detail.

Local politics at the centre of national politics

Ankara has followed the worldwide trends in terms of urbanization, the main source of employment, and economic activities. As a consequence of urban policies specifically focused on the construction industry, both the square meter area of new buildings and house sales in the city increased. In parallel to neoliberal urban policies, which were justified to facilitate foreign investment, the city became increasingly commercialized, which is visible from the rise in foreign investment.Footnote2

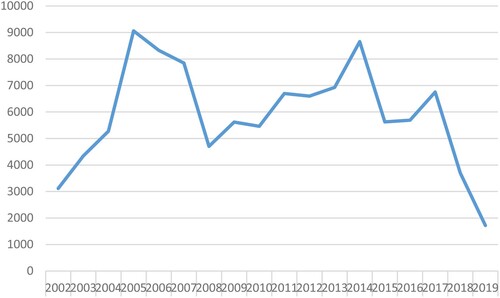

While the overall gross domestic product (GDP) of Ankara shows steady growth, the sharp downturns in sectoral growth rates reflect the negative impact of the 2008 financial crisis as well as the national-level crises in 2015 and 2017, in the construction sector in particular. Turkey’s national economy is heavily dependent on the construction industry (10% between 2002 and 2017, while that of the European Union was 6% and of Brazil was 8%) (Yeşilbağ, Citation2020). The fluctuations in construction permits reveal that such growth was based on financial urbanization and susceptible to global and national financial and sectoral crises. Furthermore, the increase in residential construction was not reflected in the housing market and therefore the growth that took place was financial (Yeşilbağ, Citation2020).

Financial urbanization reached its peak in the early 2000s in Ankara. The highest number of construction permits was granted in 2005 and fell sharply with the 2008 global financial crisis. The construction permit number reached the 2005 level only two years after (and, not coincidentally, immediately before the local elections) the promulgation of the 2012 Municipality Law. The quantity of construction permits granted gradually decreased as the 2015 and 2017 economic crises hit the Turkish economy (TUIK, Citation2019d) (). The following sections will demonstrate how the 2012 Municipality Law enabled a brief recovery in financial urbanization in Ankara.

The history of a long one-man rule

During Melih Gökçek’s 23 years of rule, Ankara Metropolitan Municipality became the setting for several controversial issues. It witnessed the use of populist policies of social assistance to garner support from the urban poor, hasty decisions, and anti-democratic rule (Keleş & Duru, Citation2008). This period saw the firing or forced resignation of experienced personnel because they were associated with the period when the opposition party held the mayor’s office in Ankara. The municipality moved away from trade unions with the largest member bases and authorized the unions politically connected to AKP for collective bargaining (Doğan, Citation2005). Moreover, during this period, municipal services were increasingly delegated to subcontractors. This arguably reduced the personnel costs of the municipality but it contributed to intractable employment precarity and seemingly permanent loss of social rights (Kutlu, Citation2010). At the same time, the cost of public services such as coal, natural gas, drinking water and public transportation also increased. The pricing of utilities and public services included high profit margins for the subcontractors and companies associated with the municipality. Bribery and changes to the borders of districts were often revealed in the bidding of subcontractors for goods and services such as construction and maintenance, natural gas, and water meters. Other controversial topics include the budget allocated for the road construction and maintenance works during 1994–99, which benefited mostly the large capital and firm owners; and city planning decisions such as those concerning overpasses and underpasses (most of which were constructed despite court orders against them) (Doğan, Citation2005). Crony relations between the municipality and private sector in terms of partnerships in provision of public goods and services constitute a clear example of municipal entrepreneurialism (Karaman, Citation2013).

Institutionalization of recentralization after the 2012 law

Turkey’s local governance system used to be based on three pillars prior to the 1980 military coup and the subsequent neoliberal transformation. The three offices that constituted the pillars of local governance were (1) the appointed governor’s office for the city; (2) the elected mayor’s offices for districts; and (3) the elected mukhtar’s offices for urban neighbourhoods and rural towns and villages outside the metropolitan area. The division of authority and tasks among the three offices allowed room for locally grounded politics despite the unitary political system of the country (Arıkboğa, Citation2015).

This system was centralized first with the 1984 Metropolitan Municipality Law Article 3030, in accordance with the neoliberal transformation initiated in the 1980s (Bayraktar, Citation2007; Kayasü & Yetişkul, Citation2014). With the 1984 law, the three pillars of the local governance system were reduced to two pillars, namely district municipalities and metropolitan municipalities for the entire city (Bayraktar, Citation2007; Gül & Batman, Citation2013; Kayasü & Yetişkul, Citation2014; Sadioğlu et al., Citation2016). According to the new law, the mayor’s office was given jurisdiction over the entire metropolitan area of cities, while the mukhtar’s offices were rendered practically powerless unless outside the metropolitan area (Arıkboğa, Citation2015; Gül & Batman, Citation2013). With this law, provinces, that is, district municipalities, began to be controlled and pressured both by the metropolitan mayor and the central government. Mayors’ power and status were significantly increased. This had adverse effects on the already weak and fragile local democracy by excluding the voices of the city residents and their elected representatives (Bayraktar, Citation2007; Kayasü & Yetişkul, Citation2014).

While this law brought a certain amount of decentralization in terms of a reduction in the central government’s exercise of power over local governments’ budgeting, central authority still retained considerable power over city planning (Kayasü & Yetişkul, Citation2014). It is possible to observe a brief period of decentralization and democratization after 2003 in an attempt to abide by the European Union’s demands related to Turkey’s bid for membership. With the enactment of the Metropolitan Municipality Law No. 5216 in 2004 and Municipality Law No. 5393 and No. 5302 in 2005, ‘the administrative and financial capacity of local administrations’ was strengthened (Bayraktar, Citation2007; Kayasü & Yetişkul, Citation2014; Kuyucu, Citation2018, p. 1157). The duties and authority of municipalities were enhanced and a stronger model for mayoralty was adopted with these laws (Sadioğlu et al., Citation2016). The law of 2005 provided a certain level of autonomy for local governments from the central authority, albeit to a limited extent (Bayraktar, Citation2007; Kayasü & Yetişkul, Citation2014; Kuyucu, Citation2018). The 2004 and 2005 reforms aimed at democratization of the decision-making processes and the local governance in general by increasing the frequency of city assembly meetings, removing the power of the administrative chief (mülki amir)Footnote3 to overrule the assembly decisions, removing the decision-making powers of the assembly committee (belediye encumeni),Footnote4 and enabling the participation of citizens, civil society organizations and other sectors of society in municipality work (Gül & Batman, Citation2013; Oktay, Citation2016b; Sadioğlu et al., Citation2016). Such changes, however, were abandoned after the victory of the AKP government in the constitutional referendum of 2010, after which the AKP gradually increased the use of anti-democratic, authoritarian and centralist measures (Kuyucu, Citation2018). The 2012 amendment to the Municipality Law formally recognized the ongoing centralization (Arıkboğa, Citation2018; Kayasü & Yetişkul, Citation2014; Kuyucu, Citation2018) and made the mayor’s office solely responsible for not only the metropolitan area but also the entire greater area of cities.

The 2012 law shifted the main unit of local governance in Turkey from metropolitan city government to metropolitan area government (Arıkboğa, Citation2014, p. 2015). The purpose of administrative rescaling was to ‘strengthen the authority of the central government and render it superior in relation to other spheres of power’ (Alkan, Citation2015, pp. 14–15). The central government justified the restructuring by the need for efficiency in decision-making (Arıkboğa, Citation2015). Indeed, the metropolitan mayor was now the most important decision-maker in major cities even bypassing the elected city council. The only exception to the mayor’s powers was the decisions on real estate investment. The central government regulates urban redevelopment projects through the Investment Monitoring and Coordination Commissions established in cities (Kandeğer & İzci, Citation2016; Kayasü & Yetişkul, Citation2014; Oktay, Citation2016a) ().

Table 1. Historical overview of metropolitan municipality laws.

The local governance system in Turkey, including metropolitan municipalities, tends to adopt the model of ‘strong mayor–weak assembly’ (Akıllı & Akıllı, Citation2014, p. 684; Arıkboğa, Citation2010, p. 2015; Bayraktar, Citation2007; Oktay, Citation2016a). After the new law and with the elimination of local participatory channels, the metropolitan mayor became ‘the only province-wide directly elected representative’, which paved the way for the concentration of decision-making power in the hands of the metropolitan mayors (Akıllı & Akıllı, Citation2014, p. 684; Oktay, Citation2016a). In this system, the executive body and municipal bureaucracy are completely under the control of the mayor. The city council does not take a leading role, nor can it directly interfere with the workings of the system. The city council undertakes the functions of representation, participation, and supervision (Arıkboğa, Citation2010, p. 2015). It supervises, directs, and affects the implementation process. With the 2012 law, the city council was weakened vis-à-vis the mayor’s office (Arıkboğa, Citation2015).

The metropolitan municipality system is implemented in 30 provinces, which include about 77% of the country’s population. It is a two-stage system in which the metropolitan municipality occupies a superior position and covers the entire city, while the district municipality covers the entire district. Together, they are now responsible for large urban and rural areas. This system has greatly reduced the number of local governments in Turkey. While this transformation led to a geographical expansion in the jurisdiction of the metropolitan municipalities, it also brought about a functional transformation as it reduced the authority and resources of district municipalities (Arıkboğa, Citation2015).

In this system, the metropolitan municipality is the main authority regarding administrative services. The 2012 law does not recognize any difference between central and peripheral districts, nor does it differentiate between the needs of districts that are highly urbanized and those that remain predominantly rural in character. No special office was created to attend to the needs of different sections of local settlements. Thus, this law appears to prefer centrality over subsidiarity, which is likely to cause problems in the actual workings of the process (Arıkboğa, Citation2015; Tataroğlu & Apaydın, Citation2016).

The city councils have a representational problem; while certain ethnic, socio-economic, or professional groups are overrepresented in the councils, the interests of other groups are not represented (Bayraktar, Citation2007). The function of representation has a significant role as it affects other functions, because if a council lacks representativeness and if its power that comes from its electorate is weak, then it is likely that its roles regarding the two other functions, that is, participation and supervision, will also be weakened (Arıkboğa, Citation2010, p. 2015).

The 2014 data on 30 metropolitan municipal councils reveal that the majority (262 out of 1861) consist of those labelled ‘shopkeepers’ (esnaf), closely followed by engineers (254) and businessmen/industrialists (238) (Erdoğan, Citation2015, p. 91; Oktay, Citation2016a). The occupational distribution of Ankara City Council in 2014 showed a similar pattern: real estate developers and private business owners constituted the majority (Ergenç, Citation2014). There were 12 contractors/real estate developers among the 140 delegates in total; however, as the occupations were based on self-descriptions by the delegates, there were many others who were known to be doing jobs or owning businesses related to the real estate and related industries (elite interview, 2014). For example, there were 17 ‘family company owners’ and 10 shopkeepers in Ankara City Council elected in 2014. In total, about one-third of the city council delegates owned private businesses that were pertinent to the city council decisions. The mere demographics of the city council were conducive to rentier relations. Overall, the institutional design of the city council prevents the residents of Ankara, or any city for that matter, from being represented demographically or as an identity group, interest group or class.

Metropolitan Municipality Law Article 5216 and Article 6360 were claimed to facilitate foreign investment and participation in the global economy, and enable more efficient local service provision and use of resources (Karaman, Citation2013; Önez Çetin, Citation2015). Cities were increasingly used ‘as a tool to generate financial resources for central government and redistribute the wealth from certain groups to others’ (Eraydın & Taşan-Kok, 2014, p. 119). Property developers emerged as key entrepreneurial actors, who were tied to the ruling party via electoral and financial links. The new laws, in reality, restructured the realms of jurisdiction of the public legal personalities, their budget allocations, and staffing polices as well as gerrymandering (İzci & Turan, Citation2013, p. 119). As a result, the existing laws designed the structure of local governance in such a way that the mayor would be the central actor in local politics and the city council would play a complementary role. The representation structure was designed to consolidate party blocs within the city council and reinforce a system defined as ‘strong mayor, weak city council’, that is the coexistence of a strong mayor with party affiliation and a weak city council (Arıkboğa, Citation2015). The mayor’s office and the city council delegates are elected positions and therefore they are expected to represent their political parties as well as their constituencies’ locally based interests. The dual allegiance of the city council delegates undermines the representativeness of the local governance bodies because the delegates tend to report to the task-based commissions and vote in the general assembly along party lines (Oktay, Citation2016a).

The local electoral system further contributes to the representative bias in the city council. The seats in the city council are distributed in a ratio to favour the political party that won the local elections. Therefore, the majority of the city council delegates are from the same political party as the mayor. The mayor is also entitled to appoint several delegates without an election. In the end, the elected members constitute not more than 60% of the city council (Erdoğan, Citation2015, p. 80). Ankara Metropolitan City Council had 140 members as of the 30 March 2014 elections. Due to changes made by the 2012 law, 32 new districts were added, and the number of council members increased by 37 in comparison with the previous term. Of the 140 members, 99 were from the AKP, 22 from the CHP, 14 from the MHP and one from the BBP; the remaining two members were independent. The decisions are made according to the simple majority rule; that is, 71 out of 140 votes suffice for a policy decision. Even if all opposition members agree on a subject matter, it is impossible for them to pass a decision that the governing party does not agree with.

In Ankara Metropolitan City Council, there are 29 commissions, and each commission has nine members. Not all decisions can be made directly in the council sessions. Decisions regarding budgeting and real estate development have to be referred to the relevant commission first (Açıkgöz, Citation2015; Oktay, Citation2016a, Citation2016b; Oktay & Şen, Citation2012). The Construction and Public Works Commission; Environment and Health Commission; Planning and Budget Commission; Education, Culture, Youth, and Sports Commission; and Transportation Commission (Municipality Law, Citation2004, Article 15, https://www.mevzuat.gov.tr/MevzuatMetin/1.5.5216.pdf) are compulsory commissions for all metropolitan city councils. In Ankara, between 2012 and 2016, the number of opposition members was too small to affect any decisions in these commissions. Members of these commissions were elected at the beginning of every term from among council members and there were no fewer than five and no more than nine members in each commission. These numbers reflect the proportion of the political party-affiliated (elected) and independent (appointed) members of the council (Açıkgöz, Citation2015; Municipality Law, Citation2004, Article 15; Oktay, Citation2016a). Issues that fall under the jurisdiction of these specialized commissions are first discussed in these commissions and then decided on in the general assembly.

Decisions that are accepted by the city council general assembly are finalized unless district mayors object within five days (Oktay & Şen, Citation2012). The opposition was unable to use this objection mechanism very effectively because even if decisions that were objected to by the district municipalities were challenged in court, they continued to be applied due to intervention by the Ministry of Environment and Urban Planning (Açıkgöz, Citation2015).

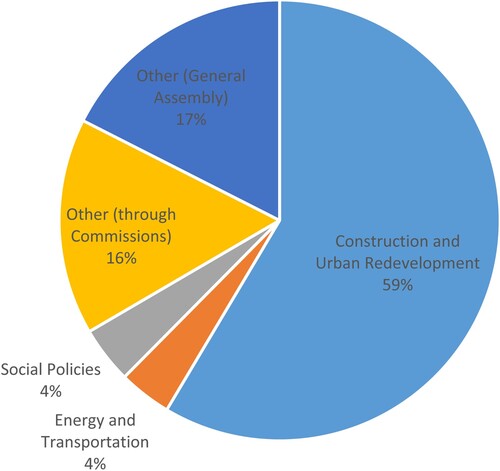

Approximately 59% of the decisions made in the city council are related to construction, demolition and urban redevelopment (). In Ankara, during the period between 2014 and 2016, most of the construction-related decisions (26%) were related to Çankaya, the largest and wealthiest district of Ankara, followed by Yenimahalle with 12% and Altındağ with 7%. These last two witnessed the construction of megaprojects and mass-housing projects, respectively, during the 2014–16 period. Accordingly, commissions related to urban redevelopment are responsible for 72% of all commission decisions.

The general assembly policy decisions are accessible by the public once they are promulgated (Açıkgöz, Citation2015; Oktay, Citation2016a; Oktay & Şen, Citation2012) but they are not comprehensible even for experts without the commission reports as background information. Commission reports, however, are regarded as confidential material and not published online (elite interview, 2016). Furthermore, some real estate development-related, potentially controversial decisions are omitted from the online version (interview with the City Report activist group member, 2014). The delegates from the opposition parties complain that there was no deliberation on crucial issues in the general assembly (elite interview, 2014).

On the Construction and Land Redevelopment Commission (CLRC), all members were contractors, and almost all of them were from the ruling party (fieldwork data, 2015). Therefore, only business interests are represented in this commission as suggested by the literature (e.g., Tansel, Citation2019). The head of the CLRC remained the same person throughout Melih Gökçek’s tenure as metropolitan mayor throughout multiple election cycles, and even though there has always been a high turnover rate in city council members (Ergenç, Citation2014). This person was a renowned real estate speculator in Ankara and acted as a gatekeeper regarding city council decisions on real estate and related sectors (elite interview, 2014). As a result of these city council decisions on land status change and urban regeneration, there were many gentrification and urban redevelopment mega projects initiated in Ankara during the 2014–16 period. For example, the Dikmen Valley project in Çankaya was extended and the North Ankara Urban Regeneration Project was completed. In both cases, TOKİ, the central-level agency responsible for housing affairs nationwide, had these two projects approved at the ministerial level. The metropolitan city council passed the decisions to allocate the land and the district municipalities of Çankaya and Altındağ, city planning experts and residents were entirely bypassed during the decision-making process. Once the land was allocated, the construction was outsourced to TOBAŞ, a private company affiliated with the Ankara Metropolitan mayor’s office (Korkmaz & Balaban, Citation2020; Topal et al., Citation2018). This example confirms our argument that the ruling party-led cronyism in Turkey (Bedirhanoğlu, Citation2019) is a factor that explains the authoritarian up-scaling of urban governance.

The fact that the majority of the fast-track decisions of the Ankara Metropolitan City Council were about construction and land redevelopment between 2014 and 2016 confirms that financialization of land took a sharp upturn after 2010 (Kayasü & Yetişkul, Citation2014). During this period, both urban and rural spaces became attractive sources of profit for private investors within the neoliberal economy (Bilgiç, Citation2018). In the same period, we see an expansion in the construction industry and gentrification projects as a significant part of neoliberal urban transformation (Bilgiç, Citation2018). Such urban transformation has taken place under the close auspices of mayors, who ‘have the last word on such decisions of public investment and public service delivery and therefore stand at the heart of these networks of urban rent’ (Bayraktar, Citation2007, p. 47). The urban and local policies of the AKP government had a tendency to favour contractors, private entrepreneurs, and urban developers with close ties to the ruling party, increasing economic growth and consolidating the AKP’s populist image by serving its supporters. Consequently, the restructuring of municipality governance led to the transfer of massive public wealth and assets to businessmen and other capitalist sectors through the concentration of decision-making powers related to urban policy and local administration in the hands of central authorities (Alkan, Citation2015; Bayraktar, Citation2007). In Ankara, the head of the Construction Commission under Mayor Gökçek was openly affiliated with a business association Gökçek had close relations with (Ilgazetesi, Citation2009). The commission head was eventually arrested for leading armed criminal networks, forced extortion and murder (Cumhuriyet, Citation2010). In order to prevent social mobilization and opposition, an authoritarian mode of neoliberalism was instituted over urban and local governance (Alkan, Citation2015). The local networks in Ankara could not name and shame the commission head until after they formed neighborhood forums in the wake of the Gezi movement in 2013 (Ergenç & Çelik, Citation2021).

Relevant to these trends in broader urban transformation and to the centralization in local politics, we observe an expansion in construction decisions and gentrification projects realized in the city council of Ankara Metropolitan Municipality. The impression is that the urban rent was divided between the political elite gathered around the ruling party and the mayor, and the economic elite that is close to the political elite.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

Our analysis demonstrates that despite the decentralization attempts in Turkey at the beginning of the 2000s, the developments in the 2010s and in particular the Metropolitan Law of 2012 clearly demonstrate that the neoliberal governance in Turkey has taken an increasingly authoritarian turn. This has had significant repercussions on urban policies and politics.

The new metropolitan system, which was consolidated after the 2014 local elections, decisively increased centralization (Arıkboğa, Citation2018, p. 2; Kuyucu, Citation2018). Alkan (Citation2015) argues that the increasingly authoritarian, anti-democratic and monopolistic tendencies of the AKP government have also been witnessed in the sphere of urban and local policies. The law contributed to ‘centralization at the local level’, which paved the way for the involvement of central bodies such as the Ministry of Environment and Urban Development, the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, the Ministry of Forestry and Water Affairs, the State Railways (TCDD), Privatization Agency, and the State Housing Agency (TOKİ) in the area of ‘spatial planning’ and ‘real estate development’ (Alkan, Citation2015, p. 15; Şengül, Citation2016). Specifically, after the passing of the 2012 law, a significant increase in executive decisions regarding land expropriations in order to facilitate infrastructural and urban regeneration projects was observed (Kuyucu, Citation2018).

The law of 2012 put serious strain on the democratic participatory character of local governance. Although the council was not representative of all social classes prior to 2012 either, voice channels were open, and council could be constrained through citizen participation and supervision. However, after the Law, the abolition of several local governmental entities throughout Turkey resulted in the closure of channels of democratic, accessible participation for many citizens and organized interest groups. Because the law could not be implemented in a participatory and transparent way, authoritarian strategies such as ‘forced evictions, expropriation, and privatization of common places’ were used (Alkan, Citation2015, p. 19).

Both the drafting and implementation of the 2012 law entailed two simultaneous processes. On the one hand the economic and political sphere of influence of the central governmental bodies increased, and on the other hand the prospects for active citizenship, democratic participation in local politics and the power of local politics contracted (Alkan, Citation2015). Since the authoritarian transformation of liberal institutions, or illiberalism, is a process (Sparke, Citation2020), authoritarian urbanism in Turkey was also met with resistance throughout the 2010s. The Gezi movement and post-Gezi neighborhood forums (Ergenç & Çelik, Citation2021) and other urban platforms empowered by the Gezi movement (Pelivan, Citation2020) constituted a bottom-up challenge to the legalization of illiberal measures introduced by the 2012 law. However, the legal institutionalization of financial urbanization prevented these citizen initiatives from developing long-lasting political agendas. This article demonstrates the specific ways in which both the citizenry and the opposition parties are excluded from urban decision-making processes.

In the specific case of Ankara Metropolitan Municipality between 2012 and 2016, parallel to the changes that came with the 2012 law, we observe an enhancement in the authority of the mayor at the expense of the elected members of the city council, a preference for rapid decision-making and efficiency over concerns of accountability and democracy, and an over-representation of decisions regarding urban redevelopment and construction as opposed to social policies, infrastructure, or the environment. These patterns are relevant both to the transformation regarding local governance at the national level and to the quality of neoliberal urban policies that the country has been exposed to, especially since 2010. We argue that such centralization, and repression of local democratic voices and citizen participation, representation, and opposition is part of a broader neoliberal authoritarian tradition to which Turkey belongs. The 2012 law was promulgated as a response to the declining votes of the AKP and, consequently, AKP received the highest share of votes in the local election in 2014 (Savaşkan, Citation2020). As the recentralization of local governance correlates with electoral politics in Turkey, an analysis of whether the changes in the city council party affiliation distribution will affect the exclusionary use of the council commission mechanism following the victory of the opposition party in the election for mayor in 2019 will contribute to the literature on fragmented authoritarianism.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the City Report (Kent Karnesi) activists in Ankara for sharing their dataset and insights when one of the authors was a part of this citizen initiative. We also thank Sumeyra Erturk for her work on the database; Sirma Altun for her excellent comments on an earlier draft; and the editor and the anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 For further information about this civil initiative, see www.kentkarnesi.org and https://www.facebook.com/kentkarnesi/ (both in Turkish).

2 The numbers of house sales in Ankara rose from 106,019 in 2012 to 144,570 in 2016 (TUIK, Citation2020). In terms of building licences according to surface area, while such permits were granted for 10,648,631 m2 in 2009, the figure rose to 29,417,842 m2 in 2017 in Ankara (TUIK, Citation2019d). Foreign investment in the city increased from 106 million Turkish liras in 2012 to 2934 million Turkish liras in 2017 (İstatistiklerle Ankara, Citation2018, p. 115).

3 A mulki amir is an appointed administrator of a locality, such as a governor.

4 The seven-person committee elected from within and by the elected members of the city council to supervise the budget decisions of the mayor’s office and oversee land confiscations. Originally designed as an intermediary organ to constrain the mayor’s office, the Encumen often created a ‘black box’ effect for the city council decisions because it prevents the participation of all city council delegates in decision-making. It was sidelined by the city council committees after the 2004/05 reforms.

REFERENCES

- Açıkgöz, M. (2015). Belediye meclisi kararları nasıl alınıyor? Solfasol Ankara’nın Gayriresmi Gazetesi, 01. Retrieved Jan 12, 2021, from https://drive.google.com/file/d/1KMNiSALy56brYd9X2zNvPLejDbEV74O6/view

- Addie, J. P. D. (2013). Metropolitics in motion: The dynamics of transportation and state reterritorialization in the Chicago and Toronto city-regions. Urban Geography, 34(2), 188–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2013.778651

- Akıllı, H., & Akıllı, H. S. (2014). Decentralization and recentralization of local governments in Turkey. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 140, 682–686. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.04.493

- Aksu Çam, Ç. (2015). Büyükşehir belediye meclisinin yapısı işleyişi ve yerel demokrasi: Adana örneği. In P. Uyan Semerci (Ed.), Yerel demokrasi sorunsalı: Büyükşehir belediye meclisleri yapısı ve işleyişi (pp. 111–132). İstanbul Bilgi Üniversitesi Yayınları.

- Albo, G., & Fanelli, C. (2014). Austerity against democracy: An authoritarian phase of neoliberalism? Socialist Project. Retrieved June 20, 2020, from http://www.socialjustice.org/uploads/pubs/AustDemoc.pdf.

- Alkan, A. (2015). New metropolitan regime of Turkey: Authoritarian urbanization via (local) governmental restructuring. Lex Localis – Journal of Local Self-Government, 13(3), 849–877. https://doi.org/10.4335/13.3.849-877(2015)

- Ankara Metropolitan Municipality General Assembly [MMGA] registers, 2014–2016. Retrieved July 27, 2020, from https://www.ankara.bel.tr/meclis-kararlari.

- Arıkboğa, E. (2010). Yerel yönetimlerde katılım ve meclislerin rolü. In Ali Kahriman (Ed.), Yerel yönetim Anlayışında Yeni Yaklaşımlar Sempozyumu (pp. 193–209). Okan Üniversitesi Yayınları.

- Arıkboğa, E. (2014). New metropolitan government regulation and changing local government system in Turkey. In U. Ömürgönülşen, & U. Sadioğlu (Eds.), Workshop on local governance and democracy in Europe and Turkey (pp. 221–234). TBB Publication.

- Arıkboğa, E. (2015). Türkiye'de dönüşen büyükşehirler ve yerel siyaset. In P. Uyan Semerci (Ed.), Yerel demokrasi sorunsalı: Büyükşehir belediye meclisleri yapısı ve işleyişi (pp. 49–72). İstanbul Bilgi Üniversitesi Yayınları.

- Arıkboğa, E. (2018). Yerinden yönetim ve merkezileşmiş büyükşehir sisteminde yetkilerin dağıtılması. Siyasal Bilimler Dergisi, 6(1), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.14782/marusbd.412624

- Aydoğan Ünal, B. (2015). Büyükşehir belediye meclisinin yapısı işleyişi ve yerel demokrasi: İzmir örneği. In P. Uyan Semerci (Ed.), Yerel demokrasi sorunsalı: Büyükşehir belediye meclisleri yapısı ve işleyişi (pp. 223–240). İstanbul Bilgi Üniversitesi Yayınları.

- Balaban, O. (2004). Krizden kaçış, krize kaçış: Türkiye’de kamu yönetimi reformu. Çağdaş Yerel Yönetimler, 13(4), 5–17. https://app.trdizin.gov.tr/makale/T0RNMk1EQXc

- Batuman, B. (2009). Hasar tespiti: Ankara’da neoliberal belediyeciligin bilançosu [damage report: The balance sheet of neoliberal municipality in Ankara]. Dosya, 13, 3–7.

- Batuman, B. (2013). City profile: Ankara. Cities, 31, 578–590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2012.05.016

- Bayraktar, S. U. (2007). Turkish municipalities: Reconsidering local democracy beyond administrative autonomy. European Journal of Turkish Studies. Social Sciences on Contemporary Turkey, https://journals.openedition.org/ejts/1103 (accessed 1/12//2022) . https://doi.org/10.4000/ejts.1103

- Bedirhanoğlu, P. (2009). Türkiye’de neoliberal otoriter devletin AKP’li yüzü. In İ Uzgel, & B. Duru (Eds.), AKP kitabı: Bir dönüşümün bilançosu (pp. 39–64). Phoenix Yayınevi.

- Bedirhanoğlu, P. (2019). Cumhurbaşkanlığı hükümet sistemi ve Türkiye’de ekonomi yönetiminin dönüşümü, Neo-liberalizmin sonu mu?. In . Kolektif (Ed.), Nuray Ergündeş için yazılar: Finansallaşma, kadın emeği ve devlet (pp. 211–230). Sosyal Araştırmalar Vakfı.

- Bilgiç, A. (2018). Reclaiming the national will: Resilience of Turkish authoritarian neoliberalism after gezi. South European Society and Politics, 23(2), 259–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2018.1477422

- Brenner, N. (2004). New state spaces: Urban governance and the rescaling of statehood. Oxford University Press.

- Bruff, I. (2014). The rise of authoritarian neoliberalism. Rethinking Marxism, 26(1), 113–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/08935696.2013.843250

- Bruff, I., & Tansel, C. B. (2019). Authoritarian neoliberalism: Trajectories of knowledge production and praxis. Globalizations, 16(3), 233–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2018.1502497

- Çetinkaya, Ö. (2015). Büyükşehir belediye meclisinin yapısı işleyişi ve yerel demokrasi: Bursa örneği. In P. Uyan Semerci (Ed.), Yerel demokrasi sorunsalı: Büyükşehir belediye meclisleri yapısı ve işleyişi (pp. 133–138). İstanbul Bilgi Üniversitesi Yayınları.

- Ceyhan, S., & Tekkanat, S. S. (2018). 6360 sayılı kanun ve Ankara iline etkileri. Bitlis Eren Üniversitesi İktisadi Ve İdari Bilimler Fakültesi Akademik İzdüşüm Dergisi, 3(2), 20–42. https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/pub/beuiibfaid/issue/37205/420757

- Çiçek, C. (2015). Büyükşehir belediye meclisinin yapısı işleyişi ve yerel demokrasi: Diyarbakır örneği. In P. Uyan Semerci (Ed.), Yerel demokrasi sorunsalı: Büyükşehir belediye meclisleri yapısı ve işleyişi (pp. 139–156). İstanbul Bilgi Üniversitesi Yayınları.

- Clua-Losada, M., & Ribera-Almandoz, O. (2017). Authoritarian neoliberalism and the disciplining of labour. In C. B. Tansel (Ed.), States of discipline: Authoritarian neoliberalism and the contested reproduction of capitalist order (pp. 29–45). Rowman and Littlefield International.

- Çolakoğlu, E. (2015). Büyükşehir belediye meclisinin yapısı işleyişi ve yerel demokrasi: Erzurum örneği. In P. Uyan Semerci (Ed.), Yerel demokrasi sorunsalı: Büyükşehir belediye meclisleri yapısı ve işleyişi (pp. 157–164). İstanbul Bilgi Üniversitesi Yayınları.

- Cox, K. R. (2013). Territory, scale, and Why capitalism matters. Territory, Politics, Governance, 1(1), 46–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2013.763734

- Çukurçayır, M. A. (2015). Büyükşehir belediye meclisinin yapısı işleyişi ve yerel demokrasi: Konya örneği. In P. Uyan Semerci (Ed.), Yerel demokrasi sorunsalı: Büyükşehir belediye meclisleri yapısı ve işleyişi (pp. 241–254). İstanbul Bilgi Üniversitesi Yayınları.

- Cumhuriyet. (2010). Gökçek'in bürokratına ‘çete lideri’ davası. Retrieved March 29, 2021, from https://www.cumhuriyet.com.tr/haber/gokcekin-burokratina-cete-lideri-davasi-420150.

- Di Giovanni, A. (2017). Urban transformation under authoritarian neoliberalism. In C. B. Tansel (Ed.), States of discipline: Authoritarian neoliberalism and the contested reproduction of capitalist order (pp. 107–127). Rowman and Littlefield International.

- Doğan, A. E. (2005). Gökçek’in Ankara’yı neo-liberal rövanşçılıkla yeniden kuruşu. Planlama, 4(2005), 130–138. https://www.spo.org.tr/resimler/ekler/d70cb65d1521172_ek.pdf

- Duru, B. (2013). Büyükşehir düzenlemesi ne anlama geliyor? Birlik (Mayıs-Haziran-Temmuz), 33–37. https://www.academia.edu/4187250/Büyükşehir_Düzenlemesi_Ne_Anlama_Geliyor

- Eraydin, A., & Taşan-Kok, T. (2014). State response to contemporary urban movements in Turkey: A critical overview of state entrepreneurialism and authoritarian interventions. Antipode, 46(1), 110–129. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12042

- Erder, S., İncioğlu, N., & Semerci, P. (2016). Büyükşehir belediye meclislerinin yapısı, işleyişi ve yerel demokrasi: Genel değerlendirme. In P. Uyan Semerci (Ed.), Yerel demokrasi sorunsalı: Büyükşehir belediye meclisleri yapısı ve işleyişi (pp. 273–284). İstanbul Bilgi Üniversitesi Yayınları.

- Erdoğan, E. (2015). Büyükşehir belediye meclisi üyelerinin profilleri üzerine bir çalışma. In P. Uyan Semerci (Ed.), Yerel demokrasi sorunsalı: Büyükşehir belediye meclisleri yapısı ve işleyişi (pp. 73–98). İstanbul Bilgi Üniversitesi Yayınları.

- Ergenç, C. (2014). Kent Karnesi Karar Alıcılarını Takip Ediyor. Solfasol Ankara’nın Gayriresmi Gazetesi, Aralık sayısı.

- Ergenç, C., & Çelik, Ö. (2021). Urban neighbourhood forums in Ankara as a commoning practice. Antipode, 53(4), 1038–1061. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12717.

- Fuller, C. (2018). Entrepreneurial urbanism, austerity and economic governance. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 11(3), 565–585. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsy023

- Gül, H., & Batman, S. (2013). Dünya ve türkiye örneklerinde metropoliten alan yönetim modelleri ve 6360 sayılı yasa. Yerel Politikalar(3), 7–47. https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/pub/yerelpolitikalar/issue/13663/165298

- Gültekin, M. N. (2015). Büyükşehir belediye meclisinin yapısı işleyişi ve yerel demokrasi: Gaziantep örneği. In P. Uyan Semerci (Ed.), Yerel demokrasi sorunsalı: Büyükşehir belediye meclisleri yapısı ve işleyişi (pp. 185–204). İstanbul Bilgi Üniversitesi Yayınları.

- Harrison, J. (2010). Networks of connectivity, territorial fragmentation, uneven development: The new politics of city-regionalism. Political Geography, 29(1), 17–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2009.12.002

- Harvey, D. (1989). From managerialism to entrepreneurialism: The transformation in urban governance in late capitalism. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 71(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/04353684.1989.11879583

- Ilgazetesi. (2009). Gökçek, Genç İşadamları'na projelerini anlattı Kaynak: Gökçek, Genç İşadamları'na projelerini anlattı. Retrieved March 29, 2021, from http://www.ilgazetesi.com.tr/gokcek-genc-isadamlarina-projelerini-anlatti-36888 h.htm.

- İstatistiklerle Ankara. (2018). İstatistiklerle Ankara. Ankara Kalkınma Ajansı.

- İzci, F., & Turan, M. (2013). Türkiye'de büyükşehir belediyesi sistemi ve 6360 sayılı yasa ile büyükşehir belediyesi sisteminde meydana gelen değişimler: Van örneği. Suleyman Demirel University Journal of Faculty of Economics & Administrative Sciences, 18(1), 117–152. https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/download/articlefile/194341

- Jessop, B. (2000). The crisis of the national spatio-temporal fix and the tendential ecological dominance of globalizing capitalism. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 24(2), 323–360. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.00251

- Jessop, B. (2002). Liberalism, neoliberalism, and urban governance: A state–theoretical perspective. Antipode, 34(3), 452–472. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8330.00250

- Jonas, A. E. (2013). City-regionalism as a contingent ‘geopolitics of capitalism’. Geopolitics, 18(2), 284–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2012.723290

- Jonas, A. E., & Moisio, S. (2018). City regionalism as geopolitical processes: A new framework for analysis. Progress in Human Geography, 42(3), 350–370. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132516679897

- Kandeğer, B., & İzci, F. (2016). Yerel özerklik bağlamında “bütünşehir yasasını” yeniden düşünmek. In Z. T. Karaman, Y. E. Özer, İG Yontar, & G. Tenikler (Eds.), Büyükşehir yönetimi ve il yönetiminin yeni yüzü (pp. 131–158). 10. Kamu Yönetimi Sempozyumu KAYSEM 10. İzmir.

- Karaman, O. (2013). Urban neoliberalism with islamic characteristics. Urban Studies, 50(16), 3412–3427. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098013482505

- Karaman, O., Sawyer, L., Schmid, C., & Wong, K. P. (2020). Plot by plot: Plotting urbanism as an ordinary process of urbanisation. Antipode, 52(4), 1122–1151. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12626

- Kayasü, S., & Yetişkul, E. (2014). Evolving legal and institutional frameworks of neoliberal urban policies in Turkey. METU Journal of the Faculty of Architecture, 31(2), 209–222. https://doi.org/10.4305/METU.JFA.2014.2.11

- Kaygusuz, Ö. (2018). Authoritarian neoliberalism and regime security in Turkey: Moving to an ‘exceptional state’ under AKP. South European Society and Politics, 23(2), 281–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2018.1480332

- Keleş, R., & Duru, B. (2008). Ankara'nın ülke kentleşmesindeki etkilerine tarihsel bir bakış. Mülkiye Dergisi, 32(261), 27–44. https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/pub/mulkiye/issue/261/759

- Korkmaz, C., & Balaban, O. (2020). Sustainability of urban regeneration in Turkey: Assessing the performance of the North Ankara urban regeneration project. Habitat International, 95, 102081. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2019.102081

- Kutlu, D. (2010). Geçici çalışmanın süreklileşmesi ve güvencesizleşme: Özel istihdam bürolarının değişen rolü. Mesleki Sağlık ve Güvenlik Dergisi, 10(35), 41–46.

- Kuyucu, T. (2018). Politics of urban regeneration in Turkey: Possibilities and limits of municipal regeneration initiatives in a highly centralized country. Urban Geography, 39(8), 1152–1176. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2018.1440125

- Lauermann, J. (2014). Competition through interurban policy making: Bidding to host megaevents as entrepreneurial networking. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 46(11), 2638–2653. https://doi.org/10.1068/a130112p

- Lauermann, J. (2018). Municipal statecraft: Revisiting the geographies of the entrepreneurial city. Progress in Human Geography, 42(2), 205–224. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132516673240

- Luger, J. (2020). Questioning planetary illiberal geographies: Territory, space and power, territory, politics. Governance, 8(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2019.1673806

- Municipality Law. (2004). Article 15. Retrieved June 26, 2020, from https://www.mevzuat.gov.tr/MevzuatMetin/1.5.5216.pdf.

- Mutlu, A. (2015). Büyükşehir belediye meclisinin yapısı işleyişi ve yerel demokrasi: Samsun örneği. In P. Uyan Semerci (Ed.), Yerel demokrasi sorunsalı: Büyükşehir belediye meclisleri yapısı ve işleyişi (pp. 255–272). İstanbul Bilgi Üniversitesi Yayınları.

- Oktay, T. (2016a). Yerel yönetim reform sonrasında türkiye’de belediye meclisleri. In Y. Demirkaya (Ed.), Türkiye’de yeni kamu yönetimi: Yerel yönetim reformu (pp. 355–386). WALD.

- Oktay, T. (2016b). Katılımcı yerel demokrasi bağlamında belediye meclisleri. In UCLG-MEWA yerel yönetim söyleşileri (pp. 113–125). http://www.tarkanoktay.net/index_htm_files/tarkan%20oktay%20UCLG%20MEWA%20soylesi%20katilimci%20yerel%20demokrasi%20belediye%20meclisi.pdf (accessed 1/12/2022).

- Oktay, T., & Şen, M. L. (2012). Belediye meclis üyeleri rehberi. Türkiye’de yerel yönetim reformu uygulamasının devamına destek projesi (LAR II: Aşama).

- Önez Çetin, Z. (2015). The critical analysis of transformation of Turkish metropolitan municipality system. Yönetim ve Ekonomi Araştırmaları Dergisi, 13(2), 1–24.

- Özden, B., Akça, İ, & Bekmen, A. (2017). Antinomies of authoritarian neoliberalism in Turkey. In C. B. Tansel (Ed.), States of discipline: Authoritarian neoliberalism and the contested reproduction of capitalist order (pp. 189–210). Rowman and Littlefield International.

- Park, B. G. (2013). State rescaling in non-western contexts. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 37(4), 1115–1122. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12074

- Peck, J. (2001). Neoliberalizing states. Progress in Human Geography, 25(2), 445–455. https://doi.org/10.1191/030913201680191772

- Pelivan, G. (2020). Going beyond the divides: Coalition attempts in the follow-up networks to the Gezi movement in istanbul. Territory, Politics, Governance, 8(4), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2020.1737207

- Phelps, N. A., & Miao, J. T. (2020). Varieties of urban entrepreneurialism. Dialogues in Human Geography, 10(3), 304–321. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820619890438

- Pinson, G., & Journel, C. M. (2016). The neoliberal city – theory, evidence, debates. Territory, Politics, Governance, 4(2), 137–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2016.1166982

- Ponzini, D., & Rossi, U. (2010). Becoming a creative city: The entrepreneurial mayor, network politics and the promise of an urban renaissance. Urban Studies, 47(5), 1037–1057. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098009353073

- Sadioğlu, U., Özacit, İ, & Ömürgönülşen, U. (2016). Yeni büyükşehir belediyesi modeli: Türkiye’de değişen/değişmeyen merkezileşme ve adem-i merkezileşme politikaları. Yasama Dergisi, 30, 70–92.

- Şahin, S. Z. (2016). Yeni Büyükşehir kanununun mekansal planlamaya etkileri: Ankara örneğinde çatışma ve çelişkiler. In Z. T. Karaman, Y. E. Özer, İG Yontar, & G. Tenikler (Eds.), Büyükşehir yönetimi ve il yönetiminin yeni yüzü (pp. 362–385). 10. Kamu Yönetimi Sempozyumu KAYSEM 10. İzmir.

- Şahin, S. Z. (2019). Yerel seçimlerde ankara'nın merkez ve çevre ilçelerine dair sosyo-mekânsal bir analiz denemesi. Ankara Araştırmaları Dergisi, 7(1), 213–223. https://doi.org/10.5505/jas.2019.84856

- Şahin, S. Z., Çekiç, A., & Gözcü, A. C. (2014). Ankara’da bir yerel yönetim monografisi yöntemi denemesi: Çankaya belediyesi örneği. Ankara Araştırmaları Dergisi, 2(2), 159–183. https://doi.org/10.5505/jas.2014.76476

- Şahin, S. Z., Çekiç, A., & Gözcü, A. C. (2015). Keçiören Belediyesi monografisi. Ankara Araştırmaları Dergisi, 3(2), 183–211. https://jag.journalagent.com/jas/pdfs/JAS_3_2_183_211.pdf

- Savaşkan, O. (2020). Political dynamics of local government reform in a development context: The case of Turkey. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 39(1), 204–225. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654420943903

- Şengül, T. (2016). Gezi başkaldırısı ertesinde kent mekanı ve siyasal alanın yeni dinamikleri. METU Journal of the Faculty of Architecture, 32(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.4305/METU.JFA.2015.1.1

- Shin, H. B. (2019). Asian urbanism. The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Urban and Regional Studies, 4, 1–10. 10.1002/9781118568446.eurs0010

- Shin, H. B., & Kim, S. H. (2016). The developmental state, speculative urbanisation and the politics of displacement in gentrifying Seoul. Urban Studies, 53(3), 540–559. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098014565745

- Sparke, M. (2020). Comparing and connecting territories of illiberal politics and neoliberal governance. Territory, Politics, Governance, 8(1), 95–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2019.1674182

- Suğur, N. (2015). Büyükşehir belediye meclisinin yapısı işleyişi ve yerel demokrasi: Eskişehir örneği. In P. Uyan Semerci (Ed.), Yerel demokrasi sorunsalı: Büyükşehir belediye meclisleri yapısı ve işleyişi (pp. 165–184). İstanbul Bilgi Üniversitesi Yayınları.

- Tansel, C. B. (2018). Authoritarian neoliberalism and democratic backsliding in Turkey: Beyond the narratives of progress. South European Society and Politics, 23(2), 197–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2018.1479945

- Tansel, C. B. (2019). Reproducing authoritarian neoliberalism in Turkey: Urban governance and state restructuring in the shadow of executive centralization. Globalizations, 16(3), 320–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2018.1502494

- Tasan-Kok, T. (2015). Analysing path dependence to understand divergence: Investigating hybrid neo-liberal urban transformation processes in Turkey. European Planning Studies, 23(11), 2184–2209. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2015.1018458

- Tataroğlu, N., & Apaydın, H. (2016). Hukukun heyulası: Fiili durumla hukuki gerçek arasında Muğla köyleri. In Z. T. Karaman, Y. E. Özer, İG Yontar, & G. Tenikler (Eds.), Büyükşehir yönetimi ve il yönetiminin yeni yüzü (pp. 246–267). 10. Kamu Yönetimi Sempozyumu KAYSEM 10. İzmir.

- Topal, A., Yalman, G., & Çelik, O. (2018). Changing modalities of urban redevelopment and housing finance in Turkey: Three mass housing projects in Ankara. Journal of Urban Affairs, 41(5), 630–653. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2018.1533378

- Topal Demiroğlu, E., & Okutan, M. E. (2015). Büyükşehir belediye meclisinin yapısı işleyişi ve yerel demokrasi: İstanbul örneği. In P. Uyan Semerci (Ed.), Yerel demokrasi sorunsalı: Büyükşehir belediye meclisleri yapısı ve işleyişi (pp. 205–222). İstanbul Bilgi Üniversitesi Yayınları.

- TUIK. (2019d). Building license according to surface area, 2002–2019. Retrieved July 30, 2020, from https://biruni.tuik.gov.tr/ilgosterge/?locale=tr.

- TUIK. (2020). House sales by provinces and years (2008–2020). Retrieved July 29, 2020, from http://www.tuik.gov.tr/PreTablo.do?alt_id=1056.