ABSTRACT

On separating from Malaysia in 1965, the People's Action Party (PAP) sought to rapidly transform Singapore into a modern, industrialized nation-state. This was deemed essential if Singapore, a small island-nation, were to survive as an independent country. Nation-building would be reliant on territorial integration, entailing the industrialization and subordination of the rural periphery by a modernizing urban core, a process referred to as internal colonization. Territorial integration was critical in Singapore as the British had focused its efforts on the port city, leaving much of the island undeveloped. While there has been significant academic interest in both land and water scarcity in Singapore, rarely are they addressed together, which, as this paper argues, is necessary to understand the wider territorialization process. This paper reveals how the gradual expansion of catchment area into different regions of the island, through reservoir construction and anti-pollution measures, facilitated, legitimized and depoliticized the comprehensive restructuring of the domestic economy, urban renewal and gentrification, and resettlement of the population. The case is made for a political ecology of the state that historicizes and politicizes territory by revealing its forgotten, contested, physical geography. The importance of internal colonization to Michel Foucault's thinking on power is also underlined.

REFRAMING THE LAND QUESTION

In 1965, the year that Singapore became an independent sovereign country, expelled from the Malaysian Federation, the state owned approximately 50% of its land surface. By 2018 this figure had increased to 90%, bringing much of this small island, over a number of tumultuous decades, under the control of an increasingly modern, territorial state. This process of land consolidation has been fundamental to Singapore's widely documented transition from ‘third world to first’ (Lee, Citation2000). Indeed, of all the resources that are considered scarce in Singapore – water, energy, population – land has been the starkest limiting factor (Chua, Citation2011). Former Prime Minister and ‘Founding Father’ of Singapore Lee Kuan Yew described the country as a ‘heart without a body’ (Lee, Citation2000, p. 3), lacking not only in natural resources but the fundamental necessity of space. Endowed with a limited, low-lying surface area of 580 km2, less than half the size of London, much of it marshy and flood-prone, land scarcity has been the overriding concern of the People's Action Party (PAP), the only party to hold office in Singapore since independence. Smallness and vulnerability have provided justification for robust intervention in a broad range of domestic issues on an emergency basis (Leifer, Citation2000). Certainly, land scarcity was linked to Singapore's command-and-control approach during an early planning session, as preparations were being made for British withdrawal: ‘Speaking from the point of view of geography, we are only a tiny island … we believe in democratic socialism, but we are seriously limited by political and economic considerations in respect of land, raw materials and natural resources’ (Hansard, Citation1961). Growth – economic and territorial – has been pursued through centralized long-term planning, under a developmental state (Liow, Citation2012). Strict social control measures have also been implemented, with respect to labour relations, political and media freedoms, civil liberties and crime prevention (Mauzy & Milne, Citation2002). Urban planning and social engineering, two sides of Singapore's development model, has dovetailed most intimately in ‘HDB’ public housing, which fragmented ethnic and communal enclaves, cleaved left-wing networks, reduced wage demands, and bound citizens to mortgage loans.

Where land is concerned, the most radical policy has been a massive programme of reclamation which has grown the island by nearly a quarter, from 580 to 720 km2. The government intends to expand land surface to approximately 780 km2 by 2030, which, as sand is obtained from Malaysia, Indonesia and Cambodia, constitutes a form of territorial annexation by import. Innovation in spatial planning has also been important, including underground complexes, floating solar panels and vertical farms. Less profitable uses of land are moved overseas, with pig farms located in Indonesia and China, a solar panel field in Australia, while major reservoirs are situated in Malaysia. Domestically, most important has been the 1966 Land Acquisition Act, allowing the state to procure land on a compulsory basis, ‘whenever any particular land is needed for any public purpose’, including for residential, commercial and industrial development. Since 1967, land parcels have been leased to private developers on 99-year contracts through regular state auctions in accordance with stringent development guidelines, centralizing land administration and encouraging efficient use. As Shatkin (Citation2014, p. 116) contends, the state's dominance of land ‘has few parallels elsewhere in the world’, providing the foundation for its growth-oriented model of urban planning. Haila (Citation2016) describes Singapore as a ‘property state’, dependent on land acquisition and real estate for its political hegemony. Although land has therefore been identified as key to Singapore's modernization, this is understood within a largely political economic register, as an asset accruing state revenue. This is a crucial insight but limits analysis in two ways. First, the exchange value of land is emphasized over its use value and affordances as a physical entity (Christophers, Citation2018; Li, Citation2014). Indeed, Haila (Citation2016, p. xxi) is ‘not interested in land as a physical thing’, focusing instead on landownership institutions. Second, this precludes a thicker analysis of how land is implicated in territorial processes (Blomley, Citation2016; Elden, Citation2010), where it functions in a strategic, environmental sense (Parenti, Citation2015). Consequently, Haila (Citation2016, p. 61) suggests the ‘Singaporean government solved the land question in a peaceful way’, which, if a political ecological lens is applied, tells only half the story.

POLITICIZING CATCHMENT IN SINGAPORE

To understand the significance of land to national modernization in Singapore, the analysis must be situated in the wider territorialization process, and specifically, the expansion of water catchment across the island. This highlights the importance of land in a material, physical register and how it features in the consolidation of territory (Dittmer, Citation2021; Elden, Citation2021; Peters et al., Citation2018; Usher, Citation2020). A political ecological perspective is necessary to examine how the PAP attained administrative control over its territory in toto, as a physical, economic and strategic entity, through the incremental augmentation of catchment. And yet, the role of water catchment in Singapore's territorialization has not been acknowledged in specialist or popular accounts, and has in fact been downplayed as the outcome of ‘non-political policies and strategies’, implemented in a manner that has been ‘matter-of-fact, not ideological’ (Tortajada et al., Citation2013, p. 3). Countering this prevailing narrative, a genealogical account of catchment expansion is offered here, which examines the complex braiding of land, infrastructure and territory as constituting a process of internal colonization. This paper reveals how the expansion of catchment area into different regions of the island, through reservoir construction and anti-pollution measures, facilitated, legitimized and depoliticized the comprehensive restructuring of the domestic economy, urban renewal and gentrification, and disciplining and resettlement of the population.

While Singapore receives a high annual rainfall, its small size, urban density and lack of lakes and aquifers has made it difficult to capture water, positioning it amongst the most water scarce countries in the world. Local catchment through reservoir development has been a key aspect of Singapore's water supply, alongside imported water from Malaysia, currently able to meet half of overall demand. Since the 2000s, recycled NEWater and desalinated water have been introduced, which can provide 65% of supply. From the 1970s, catchment has been gradually expanded from the Central Water Catchment Area (CWCA) into increasingly inhabited, urbanized areas, with catchment now constituting two-thirds of Singapore's land surface. Singapore is one of a few select countries to harvest stormwater on a large scale, channelled to 17 reservoirs via rivers, canals and drains. Stringent anti-pollution legislation was introduced in 1975 to protect water resources and lower the cost of treatment, necessitating the clearance of informal settlements and upgrading of casual, small-scale industries. Concurrently, this released prime, increasingly state-owned land for development which the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) parcelled for sale for higher value use, increasing state revenue and facilitating gentrification. The strategic if exaggerated impetus for an independent Singapore to become less reliant on water imports from Malaysia (Usher, Citation2018a, Citation2019) gave the PAP a robust domestic mandate, wrapped in up in technical, depoliticized language of water supply, to push through catchment expansion, and with it, urban renewal, economic restructuring, and intensified regulation of the population. After a century of water dependency, which placed the PAP in a compromised geopolitical position with respect to diplomatic bargaining, measures such as local catchment, desalination and recycling have effectively reversed this relationship since the early 2000s, whereby Malaysia now purchase water from Singapore.

Through this study of catchment expansion, the paper makes three broader theoretical arguments on interrelations between infrastructure, land, population, territory and the state. The paper first challenges the Westphalian ‘container’ representation of territory as a fixed legal space, still dominant in political science and international law. This depiction abstracts from reality on the ground, de-historicizes territory as a material project, and overstates the reach, power and autonomy of the nation-state. Indeed, the PAP did not inherit its territory as a static legal space but had to cultivate it through material working of the land, what Mukerji (Citation2009) calls ‘territorial engineering’. To trace the physical, on-the-ground formation of territory, as a contested, intermittent and uneven process, this paper rehabilitates the analytical framework of internal colonization. The efficacy of internal colonization for the analysis of territory – its defining feature being the subordination of traditional communities through the extension of an urbanizing core into rural peripheries – bears further consideration, particularly as this literature has fallen largely out of favour. The paper draws on Michel Foucault's engagement with internal colonization, which began during his Collège de France lectures in the early 1970s when debates around internal colonialism were at their height. While Foucault's interpretation was distinctive, interpreted in the service of his own particular interests in discipline, hygiene and urbanization, the broader internal colonialism literature appears to have informed his influential analysis of power.

Second, the paper contends that territory should be examined as a dynamic physical entity, in addition to legal space, which presents unique affordances and constraints to the exercise of state power in different environmental contexts (Boyce, Citation2016; Campling & Colás, Citation2018; Clark & Jones, Citation2017; Emel et al., Citation2011; Steinberg, Citation2009). Territorial power is realized not only in the production of abstract calculative space as many scholars have emphasized (Crampton, Citation2011), but is also conveyed through the volatile, dynamic nature of the physical earth itself, and the infrastructural systems that regulate and control its unpredictable elements, forces and processes. It is unfortunate that territorial theorization, since the mid-20th century, has tended to downplay the material environment in favour of spatial relations, overlooking the importance of physical geography to statehood (Barry, Citation2013; Usher, Citation2020). Third, the paper elucidates the linkage between the biopolitics of population control and geopolitics of territorial engineering, which has received growing critical attention (Elden, Citation2018; Grove, Citation2019; Klinke, Citation2018). Territory is increasingly conceived as a three-dimensional material volume (Billé, Citation2020; Elden, Citation2013), which underlines the administrative difficulties faced by states but also how it impresses on citizens in a physical, environmental sense. In this paper, it is revealed that catchment expansion into inhabited regions justified the surveillance and regulation of the population in the interests of pollution control, linking water, bodies and territory.

Before turning to the case study, the analytical framework of internal colonization will be considered with respect to territorial and state theorization. The paper will then provide a historical geographical account of catchment expansion, beginning with the post-Independence era of industrialization and urban renewal in 1965, and turning subsequently to late 20th-century efforts to upgrade to a high-end service economy, which took the Singapore River as its visual linchpin. By way of conclusion, the paper calls for a political ecology of the state that historicizes territory by revealing its concrete material geography, thereby countering the mainstream legal rendering that exaggerates the total spatial authority of the modern nation-state, abstracting it from its environmental context. Archival fieldwork was conducted in Singapore over 18 months, between 2011 and 2013, in the National University of Singapore, National Archives of Singapore and National Museum of Singapore. Archival triangulation was undertaken by examining annual reports from state departments with respect to newspaper archives (1831–2009) and Parliamentary records (1955–2014). Access to declassified state files was obtained from the National Archives of Singapore (NAS), which could be viewed on microfilm with special permission.

THE TERRITORY OF INTERNAL COLONIZATION

This paper employs an internal colonization framework to analyse the link between land consolidation and population control, as it draws attention to the struggle, often concealed and forgotten, which accompanies territorial integration. Here, territory is an outcome of intense domestic contestation rather than simply a legal correlate of sovereignty, necessitating subordination of interior elements by a modernizing urban core: ‘physical conquest within, not across, political boundaries’ (Calvert, Citation2001, p. 51). Internal colonialism was developed by scholars in the 1960s to describe the treatment of minority groups in Latin America and United States (Blauner, Citation1969; Gonzales-Casanova, Citation1965), but its deployment increased during the 1970s to analyse the destruction or restructuring of traditional livelihoods across the world by an integrating global capitalism. Summarizing, Love (Citation1989, p. 905) describes internal colonialism as a:

process of unequal exchange, occurring within a given state, characteristic of industrial or industrializing economies … the process involves a structural relationship between leading and lagging regions (or city and hinterland) of a territorial state, based on monopolized or oligopolized markets.

As Scott (Citation2009, p. 12) observes, ‘internal colonialism’ leads to a ‘massive reduction of vernaculars of all kinds’ – language, farming techniques, tenure systems, religious practices, architecture, inter alia. Hechter’s (Citation1975, p. 5) study of Celt pacification in Britain proved the most influential account, in which he argued that nation-states colonize internal as well as external regions, usually rural and peripheral, bringing them ‘under one national culture’. Weber (Citation1976, p. 5), in his classic study of nation-building in France, reveals how modernization occurred through forced integration of rural areas – denigrated as a ‘savage interior’ – into a unified industrial urban society. Similarly for Etkind (Citation2011, p. 2), focusing on imperial Russia, internal colonization is a process whereby a modern state establishes control over its territory, ‘filling the internal space in waves of various intensities … colonizing the heartlands’. The capacity of the modern state rests on its ability to integrate, pacify and dominate its territory, constituting a more violent genealogy that internal colonization literature seeks to reveal.

Recent studies show that traditional groups located within national territories continue to have their right to land questioned and withdrawn, to enable state-led industrialization and resource development (Lawrence, Citation2014; Palmer & Rundstrom, Citation2013). Therefore, although internal colonization fell out of favour in the 1990s, these studies indicate this was premature. Furthermore, internal colonization remains analytically useful for understanding the process of territorial integration, which has not been adequately acknowledged in the literature. First, internal colonization offers an alternative genealogical account of modern state formation from the perspective of the periphery, challenging neutral accounts of modernization and highlighting the malign impacts on traditional communities as they became assimilated into urban industrial society, revealing the violence and domination that underwrites territorial integration. Second, territory is consequently reconceived not as a static legal container but outcome of expansion and struggle between a ruling core and a dominated rural periphery. This may be orchestrated along racial and ethnic lines but not necessarily, where the cultural ‘backwardness’ of peripheral communities often serves as justification for subordination, exploitation and marginalization by technological, industrial societies (Mettam & Williams, Citation1998). Third, internal colonization recognizes that economic development is used to occasion and justify enforced integration, through technology, investment and restructuring, replacing small-scale production with capitalist industrial methods, entrenching forms of economic dependency. In Singapore, urban renewal and gentrification have been instrumental to internal colonization (see also Ghertner, Citation2015), where catchment management provided a rationale for penetrating deeper into social and economic life, legitimizing the introduction of surveillance measures and clearance of poorer communities. The targeted groups, including hawkers, farmers and boatmen, were migrants, or descendants of migrants, predominantly from China, seeking a low-skilled, informal livelihood (Colony of Singapore, Citation1950). Chinese migrants, along with those from India and Malaysia (Dobbs, Citation2003), were deemed to be culturally backward, requiring enforced assimilation into a modernizing, urbanizing country.

The growing popularity of internal colonialism presumably explains why Foucault began using the term in his lectures in the 1970s, including Penal Theories and Institutions, Psychiatric Power and Society Must Be Defended. It is not without significance that Foucault regarded the suppression of rural peasantry as key to the emergence of the French state (Foucault, Citation2019). These lectures provided the basis of Foucault's strategic model for understanding power relations, which reconceived the domestic sphere as a site of permanent struggle orchestrated via infrastructural systems, administrative practices and architectural arrangements. For Foucault, the legal and democratic institutions that characterize liberal society are a deception, a civilizing veil thrown over the machinery of power, a Hobbesian foundation myth. This Foucault (Citation2003, p. 29) called the ‘schema of Leviathan’, which represents territory in the abstract as a homogenous legal space of ‘pacified universality’ (p. 53), obscuring the contested history of its making. Critically, this schema furthers the interests of the real state, entrenching in knowledge production and international legal agreements a fixed, universal representation of territory that justifies, exaggerates and naturalizes the reach, extent and authority of the nation-state (Häkli, Citation2001). Foucault employed internal colonization precisely to challenge this unitary legal schema of territorial sovereignty.

Foucault (Citation2003, p. 103) defined ‘internal colonialism’ as a ‘boomerang effect’ whereby ‘political and juridical weapons’ of colonial subordination are turned back on domestic populations. However, it was in his earlier Psychiatric Power lectures that Foucault (Citation2006, p. 71) uses ‘internal colonization’ to describe the proliferation of disciplinary apparatuses through society with industrialization, exercised in a material, everyday register on human physical bodies rather than Hobbesian legal subjects. Foucault goes on to propose that ‘[t]here is a double movement of colonization: colonization in depth, which fed on the actions, bodies, and thoughts of individuals, and then colonization at the level of territories and surfaces’ (p. 246). The study of territory, according to Foucault, must be situated within the analytical context of biopolitics, concerning how states establish an administrative grip on populations in a biological rather than legal order. Foucault was influenced by his collaborative research in the 1970s with Centre d’Études, de Recherche et de Formation Institutionnelle (CERFI), undertaken when developing his original ideas on power (Elden, Citation2017). For CERFI, territorialization occurs in and through urbanization, via development of infrastructural and logistical systems, linked to normalization of everyday life, giving rise to the modern governmental state (Usher, Citation2018b). CERFI research on social hygiene, led by Foucault (Citation1976, p. 72), focused on the ‘administrative colonization of the entire territory’Footnote1 via the expansion of sanitation measures. Foucault in his own studies examined how social discipline and public health progressively overlapped, leading to heightened surveillance of the population, and ‘urbanization of the territory’ (Foucault, Citation2007, p. 336).

This work on sanitation, urbanization and territory can nuance thinking on the hydraulic state, which has been a longstanding preoccupation of critical theory, beginning with Wittfogel’s (Citation1957) classic study of hydraulic despotism. Wittfogel posited that development of large-scale irrigation and flood control measures in arid ancient civilizations gave rise to centralized bureaucratic authority. While its technological determinism has been widely critiqued (Banister, Citation2014), Wittfogel's co-evolutionary perspective, which foregrounds environmental factors in state formation and restructuring, remains influential in contemporary political ecological analysis (Akhter & Ormerod, Citation2015; Ley & Krause, Citation2019; Meehan, Citation2014). In respect to territorial dynamics, catchment planning and administration is critical as it explicitly relates to land ownership, transformation and control. As numerous studies have demonstrated, catchment management renders technical the political undertaking of territorial integration, legitimizing, depoliticizing and naturalizing the extension of state rule on the basis of water control (Akhter, Citation2015; Barnes, Citation2017; Carroll, Citation2012; Harris & Alatout, Citation2010; Mitchell, Citation2002; Swyngedouw, Citation2015; Worster, Citation1985). This is an expression of what Carroll (Citation2006, p. 4) terms ‘techno-territoriality’; territory constituted by hydraulic engineering, infrastructure and expertise.

Catchment planning, which takes the river basin as an integrated unit for state-led development, spread across most continents in the mid-20th century, providing a scientific justification for centralized management of hydrological and social processes (Sneddon, Citation2015). An early experiment in ‘infrastructural regionalism’ (Glass et al., Citation2019), the United States’ Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) provided the model for global proliferation of integrated catchment management, promoting water resource development on a regional scale through hydraulic and social engineering. This required far-reaching political and technical capacity, centralized under a single planning authority, to transform the river network into a controlled integrated system for flood management, hydroelectricity, navigation and agriculture. What Sneddon (Citation2015, p. 5) describes as ‘river basin ideology’, the conviction that state-led regional infrastructural development of water catchments will enable national modernization, endures in contemporary hydraulic projects, requiring clearance of people, groups and industries (Rogers & Wang, Citation2020). Swyngedouw (Citation2015, p. 50) reveals how hydraulic infrastructure enabled the ‘internal colonization’ of Spain's rural interior, predicated on territorial integration through catchment development, transforming the ‘nation's territory into a productive factory for self-sufficiency’ (Camprubí, Citation2014, p. 11). And indeed, internal colonization was an explicit policy of fascist regimes in Germany and Italy as well (Blackbourn, Citation2006; Caprotti, Citation2007), which drained, irrigated and populated territory through state violence and hydraulic engineering. This research on hydraulic state-making shows that territorialization is necessarily an environmental project, concerning land consolidation and infrastructural development as much as jurisdiction, while revealing the material history of nation-building that the legal container schema obscures instead. It is on this basis that internal colonization is mobilized as an analytical framework, which occurs at the intersection of the territorial, environmental and biopolitical, in and through the process of urbanization. As Lefebvre (Citation1996 [1968], p. 72) asserted, ‘[c]arried by the urban fabric, urban society and life penetrate the countryside. Such a way of living entails systems of objects and of values. The best known elements of the urban system of objects include water, electricity, gas’.

THE CREEP OF CATCHMENT

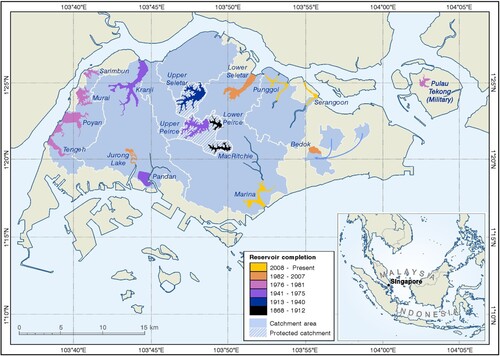

Before independence, local catchment was entirely contained within the CWCA, an uninhabited protected zone in the centre of the island, comprising just 11% of territorial space (). Under the British colonial regime, efforts to establish water supply were concentrated on the coastal port, but with a growing population of over 50,000 relying on increasingly contaminated wells and streams, the first impounding reservoir was constructed in 1868 in the CWCA, later renamed MacRitchie after the engineer who expanded it in 1894. Bolstered by the 1887 Municipal Ordinance, catchment management was carried out by an increasingly interventionist municipal authority forced to depart from its previous laissez-faire approach due to population growth. Although water planning continued to be framed in the narrow interests of colonial trade, supply had to be increased as Singapore became a major entrepôt. The Peirce and Seletar reservoirs were constructed in 1910 and 1920 respectively to augment the protected CWCA, bringing the number of impounding reservoirs to three. Nevertheless, a government report warned that more capacity was urgently required to avoid catastrophe for Singapore's 400,000 inhabitants. An agreement was reached with Malaysia to provide land for two new reservoirs, which began supplying, via a pipeline, nearly half of Singapore's water by 1932 (White & Barry, Citation1950). By the 1950s, in anticipation of the population increasing to 2 million, the search for additional domestic sources began as the CWCA was deemed insufficient. However, consultants warned against expanding catchments outside the CWCA as this would require high levels of environmental control, therefore the British secured further agreements with Malaysia in the early 1960s, guaranteeing supply for almost a century.

Figure 1. Chronological expansion of catchment and reservoirs across Singapore.

Note: Readers of the print issue can view the figure in colour online at https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2022.2056503.

During the years following independence, the PAP, which did not enjoy such cordial bilateral relations with Malaysia, significantly increased storage capacity in the CWCA: Upper Seletar was enlarged 35 times its original size in 1969, while eight years later the enlargement of Upper Peirce almost doubled the water storage capacity of the CWCA, becoming Singapore's largest reservoir (Public Utilities Board (PUB), Citation1977). It was clear, however, that CWCA storage capacity was not sufficient to support the PAP's accelerated industrialization programme, therefore reservoirs would spread across the island. With the completion of Marina Reservoir and the Punggol-Serangoon reservoir scheme in 2010 and 2011, respectively, bringing the number of domestic reservoirs to seventeen, approximately 67% of Singapore's territory is now serving as catchment. This is expected to increase to 90% by 2060 with the help of variable salinity technology. While the social consequences of catchment expansion have been far-reaching, the necessity to expand catchments into urban areas provided a convenient rationale for the state's modernization programme, facilitated by the introduction of anti-pollution measures. While the colonial regime was focused on the area around the coastal port, territorial integration was an overriding priority of the PAP, which catchment expansion enabled and indeed naturalized as it spread from the CWCA.

A Water Planning Unit was established in 1971 to conduct feasibility tests for unprotected catchments in areas outside the CWCA (PUB, Citation1971). The Water Master Plan, released in 1972, sought to achieve self-sufficiency by expanding catchment area from 11% to 75%. Initially, PUB turned its attention to river estuaries in the north and west of Singapore. The first project completed in 1975 entailed the damming of the Kranji and Pandan rivers, increasing the storage capacity on the island by 42% (PUB, Citation1978). The search for suitable estuaries was driven even further afield from the CWCA during the 1970s, resulting in the Western Catchment Scheme, completed in 1981. This scheme involved the damming up of four separate rivers to create impounding reservoirs capable of storing 31.4 million m3 of raw water. Located in unprotected catchments, the water was expected to have a different taste but be safe for drinking purposes. While the immediate area surrounding reservoirs were monitored by new patrol rangers equipped with scrambler bikes, motorboats and retractable batons, a more pervasive form of environmental control was exercised at the catchment scale. Indeed, as catchment and inhabited areas increasingly overlapped, a growing section of the population were subject to new surveillance and control measures. The Anti-Pollution Unit, formed in 1970, was placed under the Prime Minister's Office to underline its importance to national security. Prime Minister Lee underlined the importance of water pollution control in 1971:

We must develop our water resources to the full. We should be able to collect and use between 25% and 35% of the daily average of 700 million gallons of rainfall (95 in. per year) by 1975–1980. This requires stiff anti-pollution measures to reduce mineral particles and acid fumes in the air and extensive sewerage works. All sewage water from toilets, kitchens and bathrooms must go into the sewers; then, the run-off rain water can be pumped into reservoirs. (NAS, Citation2012a, p. 407)

It was the WPCDA that provided the necessary ‘teeth’ for the realization of ENV's new mandate, which the Minister for Law and the Environment introduced as a matter of urgency, declaring existing water pollution laws ‘inadequate and somewhat obsolete’ (Hansard, Citation1975a). These legislative provisions vested the government with unprecedented leverage over the urban water cycle. Water could no longer be collected without permission from PUB, effectively rendering it state property. Environmental control over farms, households, industries and other activities was extended in the interests of claiming run-off water for drinking purposes. Whereas previously only effluent from toilets and select industries was discharged into sewers, the act stipulated that all wastewater must henceforth be discarded in this way. Presciently, the Member of Parliament for River Valley expressed concern that the new Ministry would bring ‘unnecessary hardship’ on Singaporeans through ‘over-enthusiasm in the implementation of some of these policies’, and that there should be ‘flexibility in its enforcement as antipollution equipment is very expensive and this may cause a strain on the finances of some small manufacturing firms’ (Hansard, Citation1972b). However, the water authority insisted that ‘environmental control is a matter of survival’ (PUB, Citation1973, p. 1).

PHASING OUT INFORMALITY

This rationale was visited upon informal food merchants, known colloquially as hawkers, who were identified as a major threat to water resources in the 1970s. Hawkers were deemed a public nuisance, clogging up roads and throughways, and operating outside of formal, occasionally legal employment channels. Furthermore, they were considered a public health problem due to their lack of water supply for preparing food and maintaining hygiene, and were blamed for outbreaks of cholera and typhoid. Increasingly, they were reprimanded for polluting and clogging the drainage system, now a source of water supply, with litter and discarded food (Straits Times, Citation1972). State officials had also grown ‘frustrated by an uncontrolled proliferation of illegal hawkers’ (Hansard, Citation1972a), exacerbating these problems. The hawker resettlement programme commenced in 1971, which received added urgency by the pronouncements on water protection. A census was taken between 1968 and 1969 of the hawker population to facilitate the process of licensing and relocation. The new licensing information acquired from the census rendered visible a population of 28,854 hawkers, enabling more effective administration. Hawkers who failed to notify the authorities were henceforth considered illegal traders. The recently established ENV anticipated that the ‘licencing of hawkers will enable the Hawkers Branch to identify, control and contain the street hawkers’ and will allow for ‘more effective planning of raids, better deployment of officers and closer surveillance’ (ENV, Citation1972, p. 32). From 1972, licensed hawkers were resettled in large purpose-built centres fitted with sewage connections, piped water, toilet and refuse services, which were rented at a subsidized rate. The first two were constructed in 1972 and two more the subsequent year, each comprising of multiple individualized booths.

Through compartmentalization in 6 m2 booths, water consumption levels and hygiene practices could be monitored and targeted by water conservation and sanitation campaigns; addressing ‘an absence of control on environmental cleanliness and standards of personal and food hygiene’ (Straits Times, Citation1978). Water, previously available from public standpipes, was charged from 1972, made possible by partitioned booths. Standpipes were removed from Singapore to facilitate charging and rationing, which decreased from 218 in 1971 to just two in 1975 (PUB, Citation1975). As pretext for the introduction of meters, PUB cited wastage of water by hawkers that would now be curtailed through self-interest. Hawkers were entered into a national ranking system and centrally graded according to hygiene and housekeeping. If a hawker failed an initial examination, they would be unable to register as a legal food handler. As Foucault (Citation2006, p. 75) observed, ‘each body will have its place … we are never dealing with a mass, with a group … we are only ever dealing with individuals’. Hawker resettlement was deeply controversial and required cooperation with the police. They suffered loss of business and higher rental rates, leading some to violently threaten environmental inspectors. Mandatory prosthetic gloves complicated the preparation of popular dishes such as roti prata. Furthermore, all food had to be prepared on-site to allow for individual assessment, which traditionally began at home with assistance from family members. The problem of unlicensed hawkers operating illegally would persist, requiring tens of thousands of raids each year. Jail sentences could be anywhere up to 26 months. There were reports of ‘inhuman’ inspectors ‘hacking and pulling down’ the temporary stalls of unregistered hawkers, while tactics used by the ‘special squad’ included repainting vans in civilian colours and plain-clothes disguise (Hansard, Citation1976). It was suggested that the authoritarian attitude of inspectors had driven a hawker to suicide by jumping from a block of flats. Fines were doubled in the 1980s, twice the median gross monthly income, which saw hawkers finally removed from the streets by 1986.

Small-scale farmers were another group to be cleared on the premise of water security. Water pollution control had been extended into the farming sector under the ‘new concept’ and ‘totally new perception’ of unprotected catchments (PUB, Citation1973, p. 2). In 1974, the year before Kranji Reservoir was completed, nearly 3000 farms located in the catchment, tending about 30% of the country's pigs, were served quit notices citing the expense of treating polluted water. Informed that they had 18 months to vacate to non-catchment areas, farmers were urged to cooperate by government reaching out through a compliant media. However, farmers lacked information regarding alternative sites, their size, lease periods and rental prices (Straits Times, Citation1974). And indeed, the government had little intention of resettling scores of small-scale farmers as the farming sector was to be commercialized through large, corporatized farms. Ministers said to be defending ‘the fundamental principles of democratic socialism’ against ‘capitalist farmers’ pushed for government capital expenditure on infrastructure and low-interest loans, to protect a traditional sector (Hansard, Citation1974). A particularly stinging stipulation of resettlement meant that farmers tending less than 0.5 ha would not be compensated:

In order to comply with the regulations of the Ministry of the Environment … they should not pollute the water resources, they must construct a drain round the pig farms to ensure that there is proper drainage of the filthy water. But it costs a few thousand dollars to build such a sewage system. This is quite beyond the means of the small farmers. (Hansard, Citation1975b)

A RATIONALE FOR RENEWAL

The WPCDA provided the teeth for the most contentious anti-pollution campaign, symbolically announced by Prime Minister Lee at the opening of Upper Peirce Reservoir in 1977:

It should be a way of life to keep the water clear. To keep every stream, every culvert, every rivulet free from unnecessary pollution. I think the Ministry of the Environment … should make it a target in ten years to let us have fishing in the Singapore River and fishing in the Kallang River. It can be done. Because in ten years, the whole area would have been redeveloped, all sewage water will go into the sewage and run-off must be clean. (NAS, Citation2012b, p. 387)

As Straits Times (Citation1983) proclaimed, Singapore was being ‘transformed into a huge water catchment area’. Until the mid-1970s, pollution control was limited to the banks of waterways. However, the WPCDA empowered government authorities to follow pollution flows back to their source. Central to the timing of Lee's reservoir announcement was the wider economic context in which the anti-pollution campaign took place. The urban renewal programme that had defined the incumbency of the PAP turned towards the Singapore River during the late 1970s. Since attaining self-government in 1959, the PAP had focused its strategy for rapid modernization on the area located south of the Singapore River. Urban renewal increased availability of modern housing for lower income communities but slum clearance would also open city centre land for a restructured finance and service economy. The Concept Plan, introduced in 1971, envisaged a ring of satellite towns around the CWCA, decentralized industrial zones and a central business district (CBD), to serve a ‘proper economic role reflecting its high real estate value’ (URA, Citation1989a, p. 14). Rent control would be relaxed to encourage landlords to upgrade holdings and land attained through forced acquisition would be sold for significantly higher prices. The first sale of sites occurred in 1967 under the Housing and Development Board (HDB), but in 1974 the URA assumed responsibility, by which time 121 ha of informal dwellings had been transformed into hotels, shopping centres, restaurants, attractions, offices and condominiums (HDB, Citation1974).

Lee first formalized his ambition for an unpolluted Singapore River in 1969, nearly a decade before it was publicly announced, and contemporaneous with the first land sales. In a confidential memorandum, Lee requested a report be completed by drainage engineers to revive the central rivers. According to Lee, this should ensure ‘clean, translucent water, where fish, water lilies, and other water plants can grow, and both sides of the waterway planted with trees, like willows’, and crucially, ‘also provide, during heavy rains, an additional source of water supply which could be pumped to a reservoir’ (NAS, Citation1969). Marina Reservoir, completed in 2010, was therefore conceived over forty years previous, and it was this ambition that provided a rationale for catchment clearance. The engineers’ report highlighted the ‘septic conditions’ of rivers, resulting from riverside slums, work yards and hawker-stalls (p. 1). To enhance the visual and recreational potential of the central rivers, the report recommended tighter pollution control, extended sewerage and removal of contamination sources. While this supported urban renewal, it was the link made to water supply and the ‘special significance’ (p. 12) of urban catchments that would reduce social fallout of large-scale resettlement. The priority of URA, established to accelerate urban renewal, was to enhance the inner-city environment through aesthetic improvement and create a ‘Wall Street of the East’. Low-skilled labour and informal settlers would be priced out, if not moved out, to facilitate the influx of foreign high-end workers required for the service and finance economy.

Some public housing was provided in the central area, but applicants holding out for this were deemed ‘choosy’ by government and threatened with an eight year wait or higher rental prices (Straits Times, Citation1980). Lee personally advised applicants not to wait for available flats in the central district where they had lived (Straits Times, Citation1981a). With soaring land values, continued demolition of buildings and government-controlled sales, it was inevitable that rents would rapidly spiral. Some office rents would go on to rise by as much as 400% in a two-year period in the early 1980s, leading one journalist to beseech ‘if prawns can survive in the Singapore River, why can't professionals in the Singapore Republic?’ (Straits Times, Citation1981b, p. 15). And indeed, this association between aquatic life returning and increasing rental costs is pertinent as both were corollaries of urban renewal. With the URA's focus on aesthetic improvement, those dwelling and working along the Singapore River were targeted for relocation. The escalation in land sales had brought new commercial interests to the river, including the United Overseas Bank, the OCBC building, and the High Street Centre. The Singapore River Redevelopment Plan, introduced in 1985, assigned it a new economic role for the service and tourism economy.

The 10-year clean-up would cost S$300 million, but the investment would be vindicated many times over by growth in real-estate values. The Singapore River and the Kallang Basin catchments cover one-sixth of the island, which then included approximately half the country's urban area (COBSEA, Citation1986). The Kallang Basin drains five rivers, which converge with the Singapore River in Marina Bay. Given the aspirational branding scheme for Marina Bay, the assurance of clear waters from these adjoining waterways would be critical. The vastness of this catchment saw thousands of communities and businesses identified as pollution sources, some over 2 km away, including over 46,000 informal residents. And certainly, the political stakes would have been significantly higher if not linked to water supply, communicated through government reports and a pliable press: ‘The objective of the [clean-up] programme is mainly to further protect Singapore's water resources’ (ENV, Citation1978, p. 2). According to the Chief Engineer of Pollution Control, the most effective method for public relations was to emphasize the need for water resources (ENV, Citation1990). This justified the clearance of lighter boats which ferried goods between ships and the docks. The Singapore Port Authority was moving towards containerization, negating the need for lighterage. The Lighter Owners’ Association was warned that their industry would be relocated when urban redevelopment reached the banks of the Singapore River (Straits Times, Citation1970). Repair facilities had already been inconveniently relocated but from 1980 removal of lighters would be framed around water pollution. The Lighter Owners’ Association adapted their appeals, blaming drains entering the river, and suggested a body be established to enforce anti-pollution measures, but all lighters were cleared by 1986, along with informal settlers, hawkers and farmers.

URBAN WATER ASSETS

Almost 10 years after Lee's reservoir speech, water quality in central rivers had improved dramatically, evinced by the return of fish, crabs and prawns. Tests showed that dissolved oxygen levels had more than doubled and nutrient levels had decreased by a factor of 10 (COBSEA, Citation1986). A 12-day Clean Rivers Commemoration marked the conclusion of the campaign with theatrical performances, water sports and festivals, gesturing to the future role of the rivers as ‘urban water assets’ (URA, Citation1989b, p. 3), enhancing property values and creating lifestyle destinations. Clarke Quay and Boat Quay, two major leisure destinations completed in 1993 on the Singapore River, were testbeds for developer-led waterfront improvement, streamlining the tenant settlement process and phasing out rent controls. The 10-year Urban Waterfronts Master Plan for the development of Marina Bay and Kallang Basin acknowledged the ‘cleaning of our urban waterways has unleashed their hidden potential as recreational playgrounds in the city’ (URA, Citation1989b, p. 1). Remaining shipyards, gasworks and small industries at Kallang Basin would be ‘phased out in order to fully realise the area's potential as a venue for fun and recreation’ (p. 14). Petty gangsters, drug addicts and smugglers of liquor, cigarettes and marijuana had been a target of a longstanding police operation ‘to flush out undesirable elements from the waterfront’ (Straits Times, Citation1984). Inspired by waterfronts at Baltimore, Sydney and San Francisco, the objective was to yield benefits from the large amount of investment put into the clean-up, to link and line promenades and shopping fronts. The revised Concept Plan (URA, Citation1991) that would guide development for the next quarter century shifted focus from industrialization and urban renewal to the expansion of leisure opportunities to attract foreign talent.

Located on the northeast coast, the last two reservoirs to be constructed in Singapore were declared open in 2011, increasing local catchment area to nearly 70% of the island. With a combined catchment of 5500 ha, the Punggol and Serangoon reservoirs were created by damming the estuaries of their respective rivers, both of which are connected by a 4.2 km artificial waterway. These reservoirs have the capacity to supply 5% of national water demand but they also provide a large quantity of space for signature waterfront housing districts. But it was Marina Bay, a reservoir serviced by the Singapore River and Kallang Basin since 2008, which has been the government's flagship waterfront development. The Bay is an entirely artificial product of the state's planning board, constructed between 1971 and 1985 from reclaimed land. In 1986 a preliminary scoping exercise was conducted on the possibility of turning Marina Bay into a non-potable source of water supply, with catchment expansion exhausted elsewhere on the island. For the state planning authority, under its new cultural strategy to encourage activities appealing to investors and professionals, Marina Bay was destined to become the ‘place where beautiful people in sassy nightwear can flaunt their aerobicised bodies’ (URA, Citation1999, p. 96), providing a glamorous backdrop for spectacularized flesh.

The URA was given an expanded mandate to catalyse investment as the Development Agency of Marina Bay. The URA initiated design consultancy studies to produce proposals for a 3.35 km promenade around the bay, and an advisory panel was formed to evaluate submitted design proposals for the construction of Marina Barrage, to transform the bay into an attractive freshwater reservoir. Furthermore, the URA was charged with the ‘software’ development of Marina Bay, to organize cultural events, attractions and recreational activities, to ensure that plans remained ‘market orientated and attractive to investors’ (URA Citation2004), such as the F1 Powerboat World Championship. The intention was to ‘provide stimulus to generate economic activities, improve the range and quality of evening activities in the key districts, and raise the buzz and hip quotient of our city’ (URA, Citation2008, p. 46). Vibrancy, urbaneness and tolerance were essential to the image of Singapore as a global service economy, therefore the cultural predispositions of the population became a target of government strategy, to project liveability rather than docility (Oswin, Citation2019). Waterfront space, created through island-wide leisure plans and urban design guidelines, facilitated a lifestyle-oriented approach to government (Usher, Citation2018b). Indeed, biopolitical regulation of the population occurs in and through the landscape and atmosphere of territory, impressing physically and affectively on human bodies, shaping the temperament of citizens.

Marina Bay was the designated site for establishing Singapore's brand identity, providing a global stage for signature buildings, water-based events and famous views. The water serving the bay had to be pristine, and not only for drinking purposes: ‘While we are confident that the raw water collected can be treated to high drinking standards with advanced membrane technology, the challenge … will be to ensure that the water is good for recreational and other lifestyle activities’ (Hansard, Citation2005). The National Day Parade was relocated to Marina Bay on the world's largest floating stage, with patriotic videos displayed on dancing water, a display of hydro-nationalism in a distinctly postmodern register. The construction of Marina Barrage was completed in 2008, separating the sea from the freshwater bay. This created Singapore's fifteenth reservoir with a catchment area of 10,000 ha, providing 10% of water supply and ensuring a clear, tranquil surface for place management and the expansion of the CBD around Marina Bay. The reservoir has become an investment haven attracting vast amounts of foreign investment, increasing from S$900 million in 2004 to S$5.4 billion in 2006 (URA, Citation2007). Iconic buildings such as Marina Bay Sands and The Esplanade are located on the waterfront, while luxury condominiums, with penthouses selling for nearly S$30 million, have risen at its edge (Straits Times, Citation2006). Even before apartments were constructed, speculators were reselling units for triple the original price. Pangaea, an exclusive nightclub for the superrich with cocktails sold for S$32,000, is located on a floating pavilion on the bay, with access via an underground tunnel. These billionaire partygoers were presumably unaware of the measures that had been necessary to make their evening possible; the moving and parcelling of land, enforced resettlement of communities, clearing of traditional industries, and innovations in water technology and engineering. That cocktail is a culmination of sorts to a decades-long process of internal colonization.

CONCLUSIONS: HISTORICIZING TERRITORIAL SPACE

It is clear from this account that significantly more has been at stake with catchment expansion than water supply alone. And yet, this potent rationale, promulgated by politicians and civil servants since independence, has provided a technical, depoliticized basis for territorial integration, modernization and state-driven gentrification, legitimizing and naturalizing a process of internal colonization, bringing the population under a stricter programme of surveillance and regulation. When Singapore became a self-governing nation in 1959, modernization became the PAP's overriding concern, to be achieved through industrialization, urbanization and integration of the territory. A rural periphery characterized not only by unproductive flood-prone land, but an intransigent population engaged in small-scale farming and casual work, with many living in informal settlements linked with left-wing political activity, would be subject to intensifying state control. As Scott (Citation1998, p. 82) contends, with its reliance on standardization and legibility, ‘modern statecraft is largely a project of internal colonization’. There was a pronounced core–periphery dynamic whereby an urban administration attained a tighter grip of its rural areas as catchment extended from the centre of the island to the east, north and west, eventually turning south to the Singapore River, the cultural, economic and political nucleus of the nation. Disparate social groups – hawkers, farmers, lightermen and informal ‘squatters’ – were brought under the ambit of the developmental state, enabling the upgrading of the city centre for its current high-end economic role.

Overall, the contention is that water supply and pollution control have been instrumental in facilitating, legitimizing and depoliticizing successive rounds of economic restructuring, which have articulated with a broader process of territorial integration, understood together as internal colonization by urban catchment management. This account offers an alternative perspective to that of The Singapore Water Story circulated by the state, which emphasizes the government's success in achieving water security through planning, science and technology. This official narrative maintains that water resource development in Singapore has been driven by purely technical and pragmatic concerns (Tortajada et al., Citation2013). Applying a genealogical lens, this paper has revealed that water management has instead been an incontrovertibly political undertaking, a vehicle for restructuring, surveillance, gentrification and territorialization. It is important to recognize that catchment management facilitated internal colonization in an ecological register, where the hydrological profile of Singapore offered particular geophysical affordances for how territorialization unfolded. Territory prompts questions of physical intensity in addition to surface extension, which are historical as well as spatial in character, concerning the incremental harnessing of the earth's unpredictable forces. River basin planning and catchment management should be understood in this wider context of internal colonization, providing states with technical grounds for the political undertaking of territorial integration, a defining feature of 20th-century nation-building.

The conventional understanding of territorial sovereignty as a legal power container, still predominant in political science, detracts from the de facto necessity of cultivating territory. Territory is both an abstract ideal of bounded exclusive authority and a constantly failing material project oriented towards achieving that ideal in practice. A nation-state must continually assert its authority, violently if necessary, over geographical space through ongoing physical interventions: ‘Territory is never complete, but always becoming. It is also a promise the state cannot fulfil’ (Painter, Citation2010, p. 1094). The static cartographic space that depicts the sovereign territory of the nation-state on maps and in legal discourse throws a shroud over uneven geography, fractured communities and past conflicts. It is little wonder that political science enjoys greater influence in policy circles than geography, which is professionally wont to emphasize context and locality over generalization, challenging the frictionless omnipotence of territorial state power that abstract universal principles uphold instead. A way to historicize territory, to deconstruct its totalizing spatial authority, is to trace its formation in a physical register, requiring inductive, empirically detailed studies of the different environmental settings in and through which territorialization occurs, and the material impacts on the population. Territory is at once infrastructural, environmental and biopolitical; it is a living space more than it is a legal space, intricately bound up in the process of urbanization, in regional development, land consolidation, engineering works and sanitation measures.

That political geography has recently experienced an environmental turn indicates a renewed interest in physical geography, and sensitivity to these issues (Benjaminsen et al., Citation2017; Grundy-Warr et al., Citation2015). Political ecology, although somewhat insulated from state theory historically (Robertson, Citation2015), is certainly well-positioned to advance this agenda. As Huber (Citation2019, p. 556) observes, this ‘would not simply analyze the role of the state in the struggle “over” resources, but seek to understand how resources are constitutive of the modern territorial state itself’ (see also Koch & Perreault, Citation2019). Recently, Harris (Citation2017) and Loftus (Citation2020) have both rallied around a resurgent political ecology of the state, which is engaging increasingly with traditionally political geographical concerns (Ioris, Citation2014; Whitehead et al., Citation2007). This is important not only for analytical reasons but to counter the intellectual hegemony of political science on territorial matters, to build critical mass against an abstract geometry that ‘conforms to the goals of the real State’ (Deleuze & Parnet, Citation2002, p. 13). Although political theory is gradually, hesitantly coming around to this unorthodox intuition, state and international law remain stubbornly committed to Westphalian container territory, as it naturalizes authority, conceals history and silences the earth. But political space is always environmental space, where matters of state are inevitably caught up in states of matter, making territory, at the same time, contested, contingent and possible.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am very grateful to Michael Glass, Jen Nelles and Jean-Paul Addie for inviting me to attend the Network On Infrastructural Regionalism (NOIR) Water Infrastructure and Regional Governance workshop and to contribute to this special issue. I would like to thank Klaus Dodds and the anonymous reviewers for their very helpful comments during the peer review process. Maria Kaika, Erik Swyngedouw, Stephen Graham, Andrew Karvonen, Stefan Bouzarovski, Nate Millington and Nat O’Grady also provided valuable feedback on previous drafts of the paper. Thanks to Graham Bowden for producing .

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 This is translated from the French by Stuart Elden (Elden, Citation2017).

REFERENCES

- Akhter, M. (2015). Infrastructure nation: State space, hegemony, and hydraulic regionalism in Pakistan. Antipode, 47(4), 849–870. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12152

- Akhter, M., & Ormerod, K. J. (2015). The irrigation technozone: State power, expertise, and agrarian development in the U.S. West and British Punjab, 1880–1920. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 60, 123–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.01.012

- Banister, J. M. (2014). Are you Wittfogel or against him? Geophilosophy, hydro-sociality, and the state. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 57, 205–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2013.03.004

- Barnes, J. (2017). States of maintenance: Power, politics, and Egypt’s irrigation infrastructure. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 35(1), 146–164. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775816655161

- Barry, A. (2013). Material politics: Disputes along the pipeline. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Benjaminsen, T. A., Buhaug, H., McConnell, F., Sharp, J., & Steinberg, P. E. (2017). Political geography and the environment. Political Geography, 56, A1–A2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2016.11.008

- Billé, F. (Ed.). (2020). Voluminous states. Duke University Press.

- Blackbourn, D. (2006). The conquest of nature: Water, landscape, and the making of modern Germany. Pimlico.

- Blauner, R. (1969). Internal colonialism and ghetto revolt. Social Problems, 16(4), 393–408. https://doi.org/10.2307/799949

- Blomley, N. (2016). The territory of property. Progress in Human Geography, 40(5), 593–609. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132515596380

- Boyce, G. A. (2016). The rugged border: Surveillance, policing and the dynamic materiality of the US/Mexico frontier. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 34(2), 245–262. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775815611423

- Calvert, P. (2001). Internal colonisation, development and environment. Third World Quarterly, 22(1), 51–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/713701137

- Campling, L., & Colás, A. (2018). Capitalism and the sea: Sovereignty, territory and appropriation in the global ocean. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 36(4), 776–794. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775817737319

- Camprubí, L. (2014). Engineers and the making of the Francoist regime. MIT Press.

- Caprotti, F. (2007). Mussolini’s cities: Internal colonialism in Italy, 1930–1939. Cambria Press.

- Carroll, P. (2006). Science, culture, and modern state formation. University of California Press.

- Carroll, P. (2012). Water and technoscientific state formation in California. Social Studies of Science, 42(4), 489–516. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312712437977

- Christophers, B. (2018). The new enclosure. Verso.

- Chua, B.-H. (2011). Singapore as model: Planning innovations, knowledge experts. In A. Roy & A. Ong (Eds.), Worlding cities: Asian experiments and the art of being global (pp. 29–54). Oxford: Blackwell.

- Clark, J., & Jones, A. (2017). (Dis-)ordering the state: Territory in Icelandic statecraft. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 42(1), 123–138. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12154

- COBSEA. (1986). Action plan for the seas of East Asia. 14–16 January, Singapore.

- Colony of Singapore. (1950). Report of the Hawkers Inquiry Commission. Government Printing Office.

- Crampton, J. W. (2011). Cartographic calculations of territory. Progress in Human Geography, 35(1), 92–103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132509358474

- Deleuze, G., & Parnet, C. (2002). Dialogues II. Columbia University Press.

- Dittmer, J. (2021). Putting geopolitics in its place: Gibraltar and the emergence of strategic locations. Political Geography, 88(5), 102405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2021.102405

- Dobbs, S. (2003). The Singapore river: A social history, 1819–2002. Singapore University Press.

- Elden, S. (2010). Land, terrain, territory. Progress in Human Geography, 34(6), 799–817. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132510362603

- Elden, S. (2013). Secure the volume: Vertical geopolitics and the depth of power. Political Geography, 34, 35–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2012.12.009

- Elden, S. (2017). Foucault: The birth of power. Polity.

- Elden, S. (2018). Shakespearean territories. Chicago University Press.

- Elden, S. (2021). Terrain, politics, history. Dialogues in Human Geography, 11(2), 170–189. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820620951353

- Emel, J., Huber, M. T., & Makene, M. H. (2011). Extracting sovereignty: Capital, territory, and gold mining in Tanzania. Political Geography, 30(2), 70–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2010.12.007

- ENV. (1978). Annual report.

- ENV. (1990). Tidal fortunes. Landmark Books.

- Etkind, A. (2011). Internal colonization: Russia’s imperial experience. Polity Press.

- Foucault, M. (2003). Society must be defended. Picador.

- Foucault, M. (2006). Psychiatric power. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Foucault, M. (2007). Security, territory, population. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Foucault, M. (2019). Penal theories and institutions. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Foucault, M. (Ed.). (1976). Généalogie des équipements de normalisation: Les équipements sanitaires. CERFI.

- Ghertner, D. A. (2015). Rule by aesthetics: World-class city making in Delhi. Oxford University Press.

- Glass, M. R., Addie, J.-P. D., & Nelles, J. (2019). Regional infrastructures, infrastructural regionalism. Regional Studies, 53(12), 1651–1656. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1667968

- Gonzales-Casanova, P. (1965). Internal colonialism and national development. Studies in Comparative International Development, 1(4), 27–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02800542

- Grove, J. V. (2019). Savage ecology. Duke University Press.

- Grundy-Warr, C., Sithirith, M., & Li, Y. M. (2015). Volumes, fluidity and flows: Rethinking the ‘nature’ of political geography. Political Geography, 45, 93–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2014.03.002

- Haila, A. (2016). Urban land rent: Singapore as a property state. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Häkli, J. (2001). In the territory of knowledge: State-centred discourses and the construction of society. Progress in Human Geography, 25(3), 403–422. https://doi.org/10.1191/030913201680191745

- Hansard. (1961). Development Plan 1961–1964. 2, v.14.

- Hansard. (1963). Annual Budget Statement. 1, vol.22.

- Hansard. (1972a). Addenda, Ministry of the Environment. 1, vol.32.

- Hansard. (1972b). Debate on President's Address. 1, vol.32.

- Hansard. (1974). Budget, Ministry of Law and National Development. 1, vol.33.

- Hansard. (1975a). Water Pollution Control and Drainage Bill. 2, vol.34.

- Hansard. (1975b). Budget, Ministry of Law and National Development. Session 2, vol.34.

- Hansard. (1976). Budget, Ministry of the Environment. 2, vol.35.

- Hansard. (1977). Budget, Ministry of National Development. 1, vol.36.

- Hansard. (1982). Budget, Ministry of National Development. 1, vol.41.

- Hansard. (1983). Water Pollution Control and Drainage (Amendment) Bill. 1, vol.43.

- Hansard. (2005). Head L – Ministry of the Environment and Water Resources. 2, vol.81.

- Harris, L. M. (2017). Political ecologies of the state: Recent interventions and questions going forward. Political Geography, 58, 90–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2017.03.006

- Harris, L. M., & Alatout, S. (2010). Negotiating hydro-scales, forging states: Comparison of the upper Tigris/Euphrates and Jordan River basins. Political Geography, 29(3), 148–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2010.02.012

- Hechter, M. (1975). Internal colonialism: The Celtic fringe in British national development. University of California Press.

- Housing and Development Board (HDB). (1974). Annual Report 1973/74.

- Huber, M. (2019). Resource geography II: What makes resources political? Progress in Human Geography, 43(3), 553–564. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132518768604

- Ioris, A. (2014). The political ecology of the state: The basis and the evolution of environmental statehood. Routledge.

- Klinke, I. (2018). Cryptic concrete. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Koch, N., & Perreault, T. (2019). Resource nationalism. Progress in Human Geography, 43(4), 611–631. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132518781497

- Lawrence, R. (2014). Internal colonisation and indigenous resource sovereignty: Wind power developments on traditional Saami lands. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 32(6), 1036–1053. https://doi.org/10.1068/d9012

- Lee, K. Y. (2000). From third world to first. HarperCollins.

- Lefebvre, H. (1996 [1968]). Writings on cities (E. Kofman & E. Lebas, Trans. E. Kofman & E. Lebas, Eds.). Blackwell.

- Leifer, M. (2000). Singapore’s foreign policy: Coping with vulnerability. Routledge.

- Ley, L., & Krause, F. (2019). Ethnographic conversations with Wittfogel’s ghost: An introduction. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 37(7), 1151–1160. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654419873677

- Li, T. M. (2014). What is land? Assembling a resource for global investment. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 39(4), 589–602. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12065

- Liow, E. D. (2012). The neoliberal-developmental state: Singapore as case study. Critical Sociology, 38(2), 241–264. https://doi.org/10.1177/0896920511419900

- Loftus, A. (2020). Political ecology II: Whither the state? Progress in Human Geography, 44(1), 139–149. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132518803421

- Love, J. (1989). Modelling internal colonialism: History and prospect. World Development, 17(6), 905–922. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(89)90011-9

- Mauzy, D., & Milne, R. S. (2002). Singapore politics under the people's action party. Routledge.

- Meehan, K. (2014). Tool-power: Water infrastructure as wellsprings of state power. Political Geography, 57, 215–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2013.08.005

- Mettam, C., & Williams, S. (1998). Internal colonialism and cultural divisions of labour in the Soviet Republic of Estonia. Nations and Nationalism, 4(3), 363–388. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1354-5078.1998.00363.x

- Ministry of the Environment (ENV). (1972). Annual Report.

- Mitchell, T. (2002). Rule of experts: Egypt, techno-politics, modernity. University of California Press.

- Mukerji, C. (2009). Impossible engineering: Technology and territoriality on the Canal Du midi. Princeton University Press.

- National Archives of Singapore (NAS). (1969). File no. PWD 223/53, Vol.4.

- National Archives of Singapore (NAS). (2012a). The Papers of Lee Kuan Yew: Speeches, interviews and dialogues, Volume 5, 1969–1971. Seng Lee Press.

- National Archives of Singapore (NAS). (2012b). The Papers of Lee Kuan Yew: Speeches, interviews and dialogues, Volume 7, 1969–1971. Seng Lee Press.

- Oswin, N. (2019). Global city futures: Desire and development in Singapore. University of Georgia Press.

- Painter, J. (2010). Rethinking territory. Antipode, 42(5), 1090–1118. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.2010.00795.x

- Palmer, M., & Rundstrom, R. (2013). GIS, internal colonialism, and the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 103(5), 1142–1159. https://doi.org/10.1080/00045608.2012.720233

- Parenti, C. (2015). The 2013 antipode AAG lecture the environment making state: Territory, nature, and value. Antipode, 47(4), 829–848. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12134

- Peters, K., Phil, S., & Stratford, E. (Eds.). (2018). Territory beyond terra. Rowan and Littlefield.

- Public Utilities Board (PUB). (1971). Annual Report.

- Public Utilities Board (PUB). (1973). Newsletter Volume 9, number 2.

- Public Utilities Board (PUB). (1975). Annual Report.

- Public Utilities Board (PUB). (1977). Upper Peirce Reservoir.

- Public Utilities Board (PUB). (1978). Annual Report.

- Robertson, M. (2015). Environmental governance: Political ecology and the state. In T. Perreault, G. Bridge, & J. McCarthy (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of political ecology (pp. 457–466). Routledge.

- Rogers, S., & Wang, M. (2020). Producing a Chinese hydrosocial territory: A river of clean water flows north from Danjiangkou. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 38(7–8), 1308–1327. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654420917697

- Scott, J. C. (1998). Seeing like a state. Yale University Press.

- Scott, J. C. (2009). The art of not being governed: An anarchist history of upland Southeast Asia. Yale University Press.

- Shatkin, G. (2014). Reinterpreting the meaning of the ‘Singapore model’: State capitalism and urban planning. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38(1), 116–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12095

- Sneddon, C. (2015). Concrete revolution: Dams, Cold War geopolitics, and the US Bureau of Reclamation. Chicago University Press.

- Steinberg, P. E. (2009). Sovereignty, territory, and the mapping of mobility: A view from the outside. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 99(3), 467–495. https://doi.org/10.1080/00045600902931702

- Straits Times. (1970). Lighter owners want Singapore River godowns to remain, 1 October, p. 5.

- Straits Times. (1972). Sites for hawkers, 26 September, p. 10.

- Straits Times. (1974). Pig farmers told to quit in a dilemma, 26 August, p. 9.

- Straits Times. (1978). Why resiting of hawkers results in business loss, 7 May, p. 6.

- Straits Times. (1980). Higher price warning to the choosy flat applicants, 16 March, p. 4.

- Straits Times. (1981a). HDB homes at prices you can afford, 14 December, p. 1.

- Straits Times. (1981b). Driven up the wall by high rents, 2 December, p. 15.

- Straits Times. (1983). The making of a garden city, 27 December, p. 20.

- Straits Times. (1984). Three hour raid at waterfront ends masquerade, 30 July, p. 11.

- Straits Times. (2006). ‘Sub-sale offer prices for Marina Bay homes heading up’, 28 December, p. 19.

- Swyngedouw, E. (2015). Liquid power: Contested hydro-modernities in twentieth century Spain. MIT Press.

- Tortajada, C., Joshi, Y. K., & Biswas, A. K. (2013). The Singapore water story: Sustainable development in an urban city-state. Routledge.

- Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA). (1989a). The Golden Shoe.

- Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA). (1989b). Master Plan for the Urban Waterfronts at Marina Bay and Kallang Basin.

- Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA). (1991). Living the Next Lap.

- Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA). (1999). Home. Work. Play.

- Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA). (2004). Press Release: URA Moves to Implement Plans for Downtown at Marina Bay.

- Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA). (2007). Annual Report.

- Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA). (2008). Annual Report.

- Usher, M. (2018a). Worlding via water: Desalination, cluster development and the ‘stickiness’ of commodities. In J. Williams & E. Swyngedouw (Eds.), Tapping the oceans: Seawater desalination and the political ecology of water (pp. 121–148). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Usher, M. (2018b). Conduct of conduits: Engineering, desire and government through the enclosure and exposure of urban water. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 42(2), 315–333. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12524

- Usher, M. (2019). Desali-nation: Techno–diplomacy and hydraulic state restructuring through reverse osmosis membranes in Singapore. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 44(1), 110–124. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12256

- Usher, M. (2020). Territory incognita. Progress in Human Geography, 44(6), 1019–1046. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132519879492

- Weber, E. (1976). Peasants into Frenchmen: The modernization of rural France, 1870–1914. Stanford University Press.

- White, B., Barry, W., & Partners. (1950). Report on the water resources of Singapore Island.

- Whitehead, M., Jones, R., & Jones, M. (2007). The nature of the state. Oxford University Press.

- Wittfogel, K. (1957). Oriental despotism: A comparative study of total power. Yale University Press.

- Worster, D. (1985). Rivers of empire. Pantheon Books.