ABSTRACT

Incidence of hepatitis A in Wales is low (average of 0.48/100,000 inhabitants from 2004–2015). We describe a community outbreak of hepatitis A involving 3 schools (primary and secondary) in South Wales between March and June 2016 and reflect on the adequacy of the control measures used. Anyone in South Wales epidemiologically linked to a serological and/or RNA positive confirmed case of hepatitis A during the 15–50 d before onset of symptoms (diarrhea, vomiting, fever, nausea, AND jaundice, or jaundice-associated symptom) was defined as a case. Case identification was based on laboratory or GP suspicion notification, changing to active surveillance toward the end. As per national guidance, household contacts were identified and offered immunisation while in schools vaccination followed evidence of transmission. We went beyond guidance by vaccinating street play mates and in secondary schools. Mass vaccination uptake was calculated. There were 17 cases, mostly in children under 16 y of age. All cases had an epidemiological link to either a school or a household case (except primary) and no travel history. Street playing was the only epidemiological link between 2 cases in different schools. A total of 139 household contacts were identified. All schools, including secondary one, had a transmission event preceding mass vaccination (overall uptake 85%, reaching 1,574 individuals) and no tertiary cases emerged after the campaigns. We recommend extending guidance to include actions taken that helped curb this outbreak: 1) vaccinating in secondary school and 2) broadening the household contact definition. Based on our learning we further suggest 3) vaccinating upon identification of a single case who attended school while infectious regardless of source and 4) active case finding by serologically testing contacts.

Introduction

Hepatitis A is a viral infection of the liver and gastrointestinal tract. The virus is usually transmitted by the faecal–oral route through person-to-person spread or contaminated food or drink. The incubation period is 15–50 days, but usually around 28–30 d and the infectious period is around 14 d before onset of jaundice and 7 d afterwards. Citation1,Citation2 In children aged under 6 years, 70% of infections are asymptomatic and, if illness does occur, it is typically not accompanied by jaundice. Citation1 The overall case–fatality ratio is low but is higher in older patients and those with pre-existing liver disease. Citation3

Circulation of hepatitis A has decreased steadily over the past 4 decades in the European Union/European Economic Area, and an increasing proportion of the population has become susceptible. Citation4 The decrease can be attributed to several concurrent factors such as improved hygiene, sanitation, socio-economic conditions and increased availability of vaccines and food-safety measures.

In common with the rest of UK, hepatitis A incidence in Wales is low. The annual average rate of laboratory confirmed cases of hepatitis A in Wales was 0.48 per 100,000 between 2004 and 2015 (range 6 to 24 cases a year). There were 27 laboratory confirmed cases in 2016. Citation5

A safe and effective hepatitis A vaccine is available. WHO recommends no vaccination in high endemic areas, universal vaccination in intermediate endemic areas and vaccination of at-risk groups in low and very low endemic areas, Citation6 Vaccination in the UK is currently recommended at appropriate intervals for all individuals at high risk of exposure to the virus or of complications from the disease, for example, people traveling to areas of high prevalence, people with chronic liver disease or hemophilia, men who have sex with men, injecting drug users and individuals at occupational risk. Citation3

National guidance for the Prevention and Control of Hepatitis A in England and Wales, Citation2 includes advice on good hygiene practices, exclusion from school/ work until 7 d post onset of jaundice, identification of possible source of infection, contact tracing, offering prophylaxis with vaccination and/or human normal immunoglobulin (HNIG) and management of contacts in specific settings, for example, food handlers. Healthy contacts aged 1–50 and carers of healthy children under 1 (if not excluded from childcare) should only be offered vaccination while contacts aged 50 or above, or with chronic liver disease, pre-existing chronic hepatitis B or C infection or HIV infection or immunosuppression should be offered HNIG in addition to vaccination.

We describe a community outbreak of hepatitis A in South Wales and the multi-agency response, including the scope of the vaccination campaigns and enhanced surveillance of school contacts, which went beyond current national guidance.

Results

Nineteen people met the case definitions (18 confirmed, 1 probable). The 17 (out of 19) samples that were possible to sequence were genotyped as IA. Fifteen of those were related: 10 were identical; 4 were different by 1 bp; and one was shorter than 505 bp (). Two cases were identical but had a different sequence from the main outbreak one and were therefore excluded from the outbreak. In addition no epidemiological link could be identified.

Figure 1. Phylogenetic tree of outbreak sequences in a background of the genotype IA sequences from the same quarter in 2016 which are represented by •. The sequence from case 12 has not been included as it is shorter than 505bp.

Only the 17 outbreak cases were included in the analysis below.

There were 10 males (59%) and median age was 10 years, range 6 to 70 y. The majority had symptoms of jaundice (13/17) and/or vomiting (12/17). Other symptoms included abdominal pain (8/17), skin related symptoms (itchy, yellow or rash, 6/17), nausea (5/17), pale stools (4/17), diarrhea (4/17) fever (3/17) and dark urine (2/17).

Since we were unable to determine exact time of exposure for all cases it was not possible to calculate incubation periods. We were, however, able to identify the most likely transmission route for all cases except for the primary case. Transmission settings included 7/16 through a household contact, 5/16 in primary school 1, 1/16 in primary school 2, 2/16 in the secondary school, and 1/16 through street playing ().

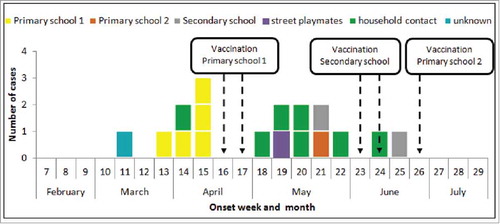

Figure 2. Epidemic curve of community outbreak of hepatitis A in South Wales, 2016, by date of earliest onset of symptoms and by setting of transmission.

Date of onset of symptoms ranged from 15th March (week 11) to 26th June 2016 (week 25) () and peaked in week 15, with all cases during the peak associated with primary school 1. The median number of days between onset of symptoms other than jaundice and onset of jaundice was 5.5 days, ranging from 1 to 75 d. The median time between onset of first symptoms and confirmatory diagnosis (using date of notification) was 10 days, range 0 to 76 d. Cases with a longer delay in their diagnosis were those who were retrospectively investigated (n = 5).

In total 139 household contacts were identified, 5 of whom either subsequently became cases, or were identified as a case retrospectively. The median number of contacts per case after notification was 10.5 (range 3 to 32 contacts). All contacts were offered hepatitis A vaccination and 18 were offered HNIG in addition. Six contacts refused to receive HNIG. The median age of household contacts who were offered vaccinated was 27, ranging from 1 to 81 and 52% were female. The median age of contacts who received HNIG was 65.5 (range 31 to 78) and 58% were female. The median number of days between onset in the source case and scheduled vaccination date in all contacts was 38 d (range 5–80) and 10 d (range 5–20) when contacts of cases that were retrospectively identified were excluded. Data on scheduled vaccination date was available for 40% of all contacts.

Three mass vaccination campaigns were organized as soon as there was evidence of transmission within a school environment (). In students at primary school 1 (vaccination dates 22nd and 27th April, week 16 and 17) uptake was 97% (222/229), in the secondary school (vaccination dates 9/10th June and 13/14th June, weeks 23 and 24) uptake was 89% (841/949) and at primary school 2 (30th June and 1st July, week 26) uptake was 93% (243/262). A community vaccination campaign took place on the 30th June, with an 86% uptake (79/92) in a nursery and pre-school club. During the school and community campaigns a total of 1,574 individuals were vaccinated.

Three cases occurred in settings where campaigns took place, 2 were most likely infected at home and the other was probably incubating infection when vaccinated 13 d after onset of symptoms in the source case.

The secondary attack rate in households was 15% (7/46) and transmission occurred in the 7 out of the 14 households involved in this outbreak.

Discussion

South Wales has low endemicity for hepatitis A, hence immunity is likely to be very low especially in children. As a consequence outbreaks will occur when infection is introduced into the community. This hepatitis A outbreak predominantly affected children under 16 y of age and is most likely to have been spread from person to person.

From the outset of the outbreak decisions about control measures went beyond current guidance. Offering vaccination to all children and staff in a school, not just the class of the affected case, was perceived as precautionary. In the guidance the risk of transmission in secondary schools is deemed to be low and consequently immunisation is not advised; there were however 2 transmission events in such a setting in this outbreak, prompting a mass vaccination campaign. The fact that one contact did not meet the household contact definition, and subsequently became a case, led to the broadening of this definition to include social contacts, such as ‘a child who has regularly played with a case during the infectious period’. Enhanced surveillance of contacts through testing for IgM, which is not part of guidance, was considered useful when most of cases are likely to be asymptomatic. This would ensure not only early identification of symptoms but allow identification of asymptomatic infection as well.

Outbreak management and control was both collaborative and timely, involving multiple agencies including health protection teams, local authorities, health boards, schools, parents, the voluntary sector, and local media as well as primary and secondary care services. We have evidence to support the view that measures were successful in curtailing the outbreak. Firstly, vaccine uptake was over 85% in all school and pre-school settings and only 3 cases occurred after the vaccination campaigns. Secondly, there was secondary transmission in half of all households (7/14) and in only one household had the secondary case been previously vaccinated. Since a case is probably infectious from about 14 d before onset of jaundice it is very likely that exposure had happened before onset in the source case and being vaccinated 9 d after onset did not change the course of infection. Thirdly, the definition used for household contact allowed the identification of an extended circle of contacts almost all of whom were offered vaccination. Fourthly estimates suggest that up to 80% of secondary cases can be prevented if contacts are vaccinated within 14 d of last exposure to a source case. Citation3 In our outbreak, median time from onset of symptoms to diagnosis was 10 d for all cases. When contacts of cases that were retrospectively identified are excluded, the range was from 2 to 20 d. Sixteen out of 24 remaining contacts (66%) were offered vaccination less than 14 d after source case onset date.

There were strengths and limitations to this approach. Immunisation of whole schools, both primary and secondary, represents a significant investment of health service resources and an opportunity cost to other prevention programmes. Investigation of a wider range of social contacts, beyond the usual household contacts, is also resource heavy, raising levels of anxiety in a wider group of otherwise healthy individuals and exposing more people to potentially unnecessary immunisation. Similarly, enhanced surveillance that requires testing of blood samples from asymptomatic children for IgM represents, at best an inconvenience, and at worst potential harm to children undergoing the blood-letting procedure. Extra testing also raises the likelihood of identifying false negatives and therefore giving false reassurance to children and their families. The outbreak control team (OCT) decisions on testing were taken with the aim of early recognition to allow prompt intervention to interrupt transmission. In recognition of the limitations of blood testing in children, the potential of PCR testing of stools for hepatitis A started being explored during the latter stages of the outbreak. This was felt to have the advantage of being less invasive than blood testing and to have the potential to give an earlier positive result than a blood sample.

Despite the success of the control measures there were lessons learned for future outbreaks. Confirmation of date of vaccination in contacts would have been useful for a more comprehensive vaccine uptake figure. This is not information routinely collected by health protection teams. Since hepatitis A is often asymptomatic in children, the extent of the outbreak and the vaccine effectiveness in schools could only be accurately assessed by a pre and a post-vaccine seroprevalence survey of school children, concurrent with the outbreak investigation. Citation8 These surveys would have allowed us distinguish between infection and vaccine induced immunity and thus to calculate specific attack rates among vaccinated and unvaccinated groups. We understand that this descriptive study provides limited evidence to support the success of the control measures undertaken and that the calculation of vaccine effectiveness would have made our case stronger. However, we recognize that this will not be possible in all outbreaks owing to several practical and logistical reasons.

Given the continuing risk of outbreaks in areas of low endemicity and based on our experience we recommend revision and extension of current national guidance to include: a) a broader household contact definition, as suggested in methods; b) vaccination of at least part of a school after identification of a single case who attended school while infectious, regardless of infection source; waiting for evidence of transmission was felt to have delayed containment in all 3 schools; c) vaccination in secondary schools as per the primary school guidance; d) active case finding (enhanced surveillance) by serologically testing contacts. In future community outbreaks, testing of stool samples should be performed alongside a blood test to assess comparative sensitivity and speed of result. Additionally, immunisation dates of contacts should be recorded. A pre and a post-vaccine salivary seroprevalence survey, where feasible, is also recommended to assess vaccine-effectiveness, give an indication of the incidence in communities where there are no recent studies and lastly to assess cost-effectiveness of mass vaccination. Citation8

In conclusion, the control measures taken that went beyond guidance have contributed to curb this hepatitis A community outbreak. Despite prompt investigation and good coordination between OCT members, the source of this hepatitis A outbreak was not ascertained. The genotype IA identified in this outbreak is the predominant subtype circulating in Europe. Citation9 The fact that no cases reported recent travel implies that hepatitis A is circulating undetected in the community. There is some evidence of substantial under-reporting of hepatitis A infection in the UK. Citation10 We also experienced some vaccine stock shortages due to the large number of contacts offered immunisation. If further community outbreaks of hepatitis A occur in the UK this may raise the question of whether hepatitis A vaccine should be included in the routine childhood vaccination schedule. Finally, outbreaks such as this offer the perfect opportunity to expand our knowledge on the epidemiology of a specific infectious agent and to explore control measures beyond the scope of the recognized current guidance. Hence, efforts should be made to have information that is complete and that would, for instance, allow to determine vaccine effectiveness. In addition, it is crucial to share these experiences. Citation11

Methods

A community outbreak of hepatitis A occurred in South Wales in which 17 cases were identified. The onset of symptoms in the primary case was on the 15th March and in the last case was on the 26th June 2016. The outbreak affected predominantly school age children and there was evidence of transmission within both primary and secondary school settings. The following case definitions were developed:

Confirmed case - Anyone in South Wales with an elevated level of IgM antibodies to hepatitis A virus and/or RNA detectable in blood, with a related viral RNA sequence, in a sample taken after 1st January 2016.

If the person was recently vaccinated (within 6 months) they were only deemed a confirmed case if they had either RNA or IgM detected TOGETHER with clinical symptoms of jaundice.

Probable case - Anyone in South Wales with an epidemiological link to a confirmed case of hepatitis A during the 15–50 d before onset of symptoms and or before marker identification: one of diarrhea, vomiting, fever, nausea, AND one of the following:

-

jaundice

-

elevated serum aminotransferase levels

-

jaundice associated symptoms (pale stools, dark urine or itchy skin)

after the 1st of January 2016.

Case excluded from the outbreak - An individual with hepatitis A whose virus was of a different sequence to the main outbreak one OR for whom an epidemiological link was not found after investigation OR for whom an alternative risk factor was found.

Household contact - a) A person living in the same household as a case or regularly sharing food or toilet facilities with a case during the infectious period. This would include extended family members who frequently visit the household and childminders, where the child attends, and their families; b) A person who had eaten food prepared by a case during the infectious period; c) A person who had been involved in nappy changing or assistance with toileting of a case during the infectious period; d) A child who had regularly played with a case during the infectious period.

Date of notification - Date when the Health Protection Team (HPT) first learns about a new case. This can be the date when laboratory notifies a hepatitis A Virus (HAV) positive result; the date when a GP reports their suspicion of a patient with hepatitis A symptoms; or the date when a case investigation suggests that a contact might actually be a case as well.

Infectious period - Cases were assumed to be infectious from 14 d before the onset of jaundice until 7 d afterward. Citation2

Data on cases were collected using a standard questionnaire on hepatitis A, Citation7 either through telephone or face-to-face interviews conducted by an environmental health officer (EHO) or by a telephone enquiry performed by the local health protection team (HPT). Data on contacts were also collected by the HPT from each case. A minimum epidemiological data set was developed and completed for all cases based on 2 main data sources: case notes from HPTs and standard hepatitis A questionnaires. Data were subsequently entered and stored on EpiData Entry software.

Hepatitis A IgM testing was performed on blood specimens by enzyme immunoassay (EIA) methods in local laboratories. The presence of viral RNA was confirmed through a nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) positive test, amplifying the VP1/2PA junction, with subsequent sequencing of the resulting 505 base pairs (bp) sequence at Virus Reference Department, Public Health England, London.

Cases were described in terms of their demographic and symptomatic characteristics as well as their likely transmission or exposure setting. Data on cases were exported from EpiData Entry and analyzed in Excel.

A total of 16 outbreak team meetings took place between April, when the outbreak was declared, and September 2016 when the outbreak was declared over. Choice of control measures was based on guidance, adjusted iteratively as and when the need arose. Citation2 From the outset, the OCT decided to take action that went beyond current guidance. These actions included: a) offer of vaccination to all children and staff in a school, not just the class of the affected case; b) offer of vaccination to children in a secondary school setting where transmission was known to have occurred, not only in primary school or early years settings; c) broadening of the definition of contacts to include social contacts such as ‘a child who has regularly played with a case during the infectious period’; d) enhanced surveillance, including wider testing of school contacts, based upon identification of increased risk of hepatitis A transmission associated with sharing of a table in class.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

The OCT acknowledges the high level of cooperation given by schools, voluntary organisations and families involved in this outbreak. The OCT included representation from Aneurin Bevan University Health Board, Cwm Taf University Health Board, Hywel Dda University Health Board, Caerphilly County Borough Council, Rhondda Cynon Taf County Borough Council, Merthyr County Borough Council and Carmarthenshire County Council. The OCT thanks Public Health Wales laboratories and the Virus Reference Department, Public Health England, for their support during this outbreak. Finally the authors would like to thank Dr. Meirion Evans and Dr. Marion Muehlen (EPIET supervisor and coordinator) for critically reviewing the manuscript.

References

- Centre for Disease Prevention and Control . Hepatitis A Questions and Answers for Health Professionals. Division of Viral Hepatitis, Atlanta, GA, USA. July 2016 . [Accessed December 2016 ]. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/HAV/HAVfaq.htm#A5

- Public Health England . Guidance for the Prevention and Control of Hepatitis A Infection. November 2009 [Accessed October 2016 ]. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/363023/Guidance_for_the_Prevention_and_Control_of_Hepatitis_A_Infection.pdf

- Immunisation against infectious diseases, the Green Book . Hepatitis A chapter (p 143-160). London, UK: Public Health England. December 2013. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/263309/Green_Book_Chapter_17_v2_0.pdf

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control . Hepatitis A virus in the EU/EEA, 1975–2014. Stockholm: ECDC; 2016. [Accessed on October 2016]. https://ecdc.europa.eu/sites/portal/files/media/en/publications/Publications/hepatitis-a-virus-EU-EEA-1975-2014.pdf

- Public Health Wales . Hepatitis A webpage. June 2016 [Accessed October 2016 ] http://www.wales.nhs.uk/sites3/page.cfm?orgId=457&pid=25967

- World Health Organisation . WHO position paper on hepatitis A vaccines: June 2012—Recommendations. Vaccine 2013; 31(2):285-6. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264410X12015757; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.10.102

- Public Health England . Hepatitis A: case questionnaire. December 2016 [Accessed April-June 2016 ]. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/hepatitis-a-case-questionnaire

- Taylor-Robinson DC , Regan M , Crowcroft N , Parry JV , Dardamissis E. Exploration of cost effectiveness of active vaccination in the control of a school outbreak of hepatitis A in a deprived community in the United Kingdom. Euro Surveill 2007; 12(12):E5-6. pii = 752. Available online: http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=752

- Severi E , Verhoef L , Thornton L , Guzman-Herrador BR , Faber M , Sundqvist L , Rimhanen-Finne R , Roque-Afonso AM , Ngui SL , Allerberger F et al. Large and prolonged food-borne multistate hepatitis A outbreak in Europe associated with consumption of frozen berries, 2013 to 2014. Euro Surveill 2015; 20(29):21192. Article DOI: https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES2015.20.29.21192

- Matin N , Grant A , Granerod J , Crowcroft N . Hepatitis A surveillance in England – how many cases are not reported and does it really matter? Epidemiol Infect 2006; 134(6):1299-302. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2870506/; https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268806006194

- Gossner CM , Severi E , Danielsson N , Hutin Y , Coulombier D . Changing hepatitis A epidemiology in the European Union: new challenges and opportunities. Euro Surveill 2015; 20(16):21101. Article DOI: https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES2015.20.16.21101; https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES2015.20.16.21101