ABSTRACT

Public health benefits of childhood vaccinations risk being derailed by low vaccination coverage in low and middle-income countries. One reason for the low coverage is poor parental knowledge of the importance of completing vaccination schedules. We therefore assessed the effects on childhood vaccination coverage, of educating parents and other persons assuming the parental role. We prospectively registered the systematic review, published the protocol, and used standard Cochrane methods to collect and synthesise the evidence. We found six eligible randomised trials with 4248 participants. Three trials assessed health-facility based education of mothers on the importance of completing vaccination schedules; immediately after birth and three months later (one study) or during the first vaccination visit (two studies). The other trials assessed community-based education, including information campaigns on the importance of vaccines using audiotaped presentations and leaflet distributions (one study); structured group discussions on benefits and costs of childhood vaccination and local action plans for improving vaccine uptake (one study); and home-based information sessions using graphic cards showing benefits and costs of childhood vaccinations and location of vaccination centres (one study). Combining the data shows that these interventions lead to substantial improvements in childhood vaccination coverage (relative increase 36%, 95% confidence interval 14% to 62%). There was no difference between the effects of community-based and facility-based education. Therefore, education in communities and health facilities on the importance of childhood vaccinations should be integrated into all vaccination programmes in low and middle-income countries; accompanied by robust monitoring of impacts and use of data for action.

Introduction

Vaccination is vital not only in averting infections, but also in mitigating the severity of infectious diseases and preventing some cancers.Citation1,Citation2 However, childhood vaccination coverage remains low in many low and middle-income countries, resulting in millions of vaccine-preventable child deaths each yearCitation2-4 The low vaccination coverage has been attributed to many reasons, including (but not limited to) parental knowledge and attitudes, and inadequate information and communication.Citation4 In particular, poor understanding of the benefits of vaccines and vaccination schedules among parents is associated with low childhood vaccination coverage.Citation5

Poor understanding of the vaccine benefits may be due to conflicting information parents receive about the importance and safety of vaccines.Citation6 Therefore, it is important that parents and persons with parental roles are provided accurate information on the benefits of childhood vaccinations and adverse events following vaccination, so that they can make informed decisions regarding vaccination of their children.Citation6-9 Active engagement and effective communication between the providers and recipients of vaccination services may be effective in improving vaccination coverage.Citation10,Citation11 We therefore conducted this systematic review to assess the effects of interventions for educating parents, compared to standard vaccination practices, on vaccination coverage in low and middle-income countries.

Methods

We registered this systematic review in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews and published the protocol in a peer-reviewed journal.Citation12,Citation13 Studies eligible for inclusion in the review were randomised trials conducted in low or middle-income countries, as defined by the World Bank.Citation14

We considered any intervention aimed at educating parents about the importance of childhood vaccinations, compared to standard vaccination practices. We defined parents as parents, legal guardians, or other persons assuming the parental role. Our outcome of interest was coverage with three doses of diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis containing vaccines (DTP3) or other vaccination status as reported by the trial authors.

We conducted a comprehensive search of peer-reviewed literature in multiple electronic databases; including PubMed, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Web of Science, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health (CINAHL), and PDQ (Pretty Darn Quick) Evidence. We conducted the initial search in May 2015, with an update in June 2016. Appendix 1 shows the search strategy we used for the various electronic databases. In addition, we searched the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, Clinicaltrials.gov, and reference lists of relevant reviews.

The output from the May 2015 search was independently screened for potentially eligible studies by LA Lukusa (LAL) and NN Mbeye (NNM). The output from the June 2016 search was independently screened by VN Ndze (VNN) and CS Wiysonge (CSW). Full texts of potentially eligible studies were retrieved and the two researchers independently assessed them for eligibility against the study inclusion criteria. All potentially eligible studies were published in English. At each stage, the two respective researchers compared their results and resolved disagreements by discussion and consensus.

LAL and VNN extracted data from eligible studies in duplicate, using a pre-designed and pilot-tested data collection form); and compared their results and resolved discrepancies by discussion and consensus. The data extracted included study design and methods, country setting, participant characteristics, intervention characteristics, outcome measures, and outcome data. The two authors also independently assessed the risk of bias in each included study using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool.Citation15 We assessed the risk of selection bias by considering the adequacy of random sequence generation and allocation concealment, and the risk of performance bias by considering blinding of participants and personnel. For the risk of detection bias we assessed the blinding of outcome assessors. We used completeness of outcome data to assess the risk of attrition bias, and the completeness of outcome reporting for the risk of reporting bias. For each domain, we classified the risk of bias as low if the criterion was adequately addressed, high if the criterion was not adequately addressed, and unclear if the information provided was not sufficient to make an informed judgement. We summarised the assessment and categorised each included study either as having a low or a high risk of bias. Any study that had a high risk of selection, detection or attrition bias was categorised as having a high risk of bias. All other studies were considered to have a low risk of bias.

We conducted data analyses using the Cochrane Review Manager software (http://ims.cochrane.org/RevMan). For each included study, we calculated the natural logarithm of the risk ratio (RR) and its standard error. We then expressed the result of each study as a RR with its 95% confidence interval (CI). We included data from two eligible cluster randomised trials after controlling for the design effect, using the intra-cluster correlation coefficient.Citation15

We assessed statistical heterogeneity using the chi-squared test of homogeneity, with significance defined at the 10% alpha level. When there was significant statistical heterogeneity, we used the random effects model to pool study results and assessed the source of heterogeneity using subgroup analyses. We defined subgroups by type of intervention i.e. community-based versus facility-based education. In addition, we quantified heterogeneity using the Higgins' I-squared statistic.Citation15

We assessed the certainty of the evidence for each outcome using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach.Citation16

Results

The two literature searches generated a total of 3568 records, and removing duplicates resulted to 3537 records. After screening summaries of the records, we discarded 3527 clearly irrelevant records. Of the 10 potentially eligible studies, we included six in the review.Citation17-21 The remaining four studies were excluded as they were not randomized trials.Citation22-25 shows the search and selection of studies for this review. summarises the characteristics of the six included studies.

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies.

Three studies assessed the effects of educating parents in communities, outside of health facilities.Citation5,Citation17,Citation19 One study was conducted in Karachi, Pakistan, with 179 mothers in the education group and 178 in the “no-education” control group.Citation5 The second study was conducted among 18 education and 14 control clusters in Lasbela district in Pakistan.Citation17 The third study was undertaken in Uttar Pradesh, India, among 11 education and 10 control clusters.Citation19 These studies assessed the vaccination status of children through vaccination cards,Citation5 or by self-reports by parents.Citation17,Citation19

The other three studies assessed the effects of educating parents at health facilities.Citation18,Citation20,Citation21 The first study was conducted in Kathmandu, Nepal, with 205 mothers in the education group and 198 mothers in the control group.Citation18 The second study, undertaken in Karachi, Pakistan, had 375 mothers each in the education and control arms.Citation20 The last study, also conducted in Karachi, Pakistan, randomised 376 mothers to receive education and 378 in the control “no education” arm.Citation21 The studies assessed vaccination coverage through self-reports,Citation18 or vaccination cards.Citation20,Citation21

One study reported including information of adverse events following vaccination in discussions with parents.Citation17

All six studies had adequate randomisation sequence generation. One study had adequate allocation concealment,Citation17 but it was unclear whether the other five had adequate allocation concealment.Citation5,Citation18-21 Outcome assessors were not aware of intervention allocations in four studies, but this was not the case in the remaining two.Citation20,Citation21 One study had a high proportion of participants lost to follow-up (21–29% in each arm),Citation18 but the others had a minimal proportion of participants lost to follow-up. Based on pre-specified criteria, we judged three studies to have a high risk of bias.Citation18,Citation20,Citation21, shows a summary of the risk of bias in included studies.

Table 2. Summary of risk of bias in included studies.

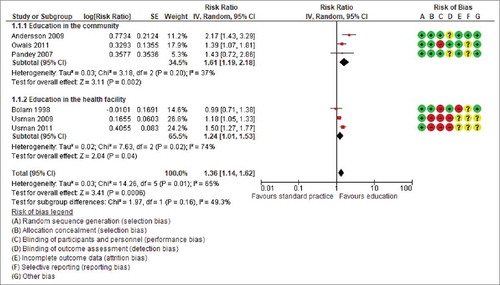

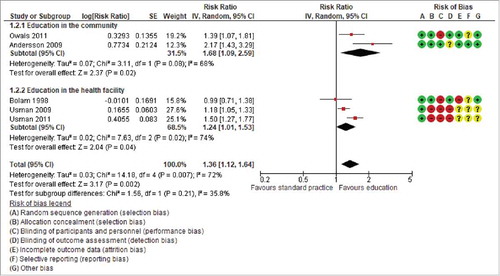

Three studies assessed the effects of educating caregivers in communities, outside of health facilities.Citation5,Citation17,Citation19 Two of these studies reported DTP3 coverageCitation5,Citation17 and the third reported coverage with at least one childhood vaccine.Citation19 The latter was a cluster-randomised trial conducted from May 2004 to May 2005 in Uttar Pradesh, India, in which Pandey and colleagues found the vaccination coverage in the intervention and control clusters to be 72% (386/536) and 46% (225/489) respectively.Citation19 In the second cluster randomised trial, conducted in Lasbela district of Balochistan province of Pakistan, from the spring of 2005 to the spring of 2007, Andersson and colleagues reported 53% (283/535) DTP3 coverage in intervention clusters compared to 24% (103/422) in control clusters.Citation17 The third study was an individually randomised trial conducted by Owais and colleagues from August 2008 to March 2009 in Karachi Pakistan.Citation5 The investigators reported DTP3 coverage of 72% (129/179) in the intervention group and 52% (92/178) in the control group. Pooling the data from the studies shows that community-based education improves childhood vaccination coverage (three trials, 2339 participants: RR 1.61, 95% CI 1.19 to 2.18, I2 = 37%) ().

The three studies that assessed facility-based education reported DTP3 coverage.Citation18,Citation20,Citation21 The coverage in the education compared to no-education arms was respectively 87% (179/205) and 85% (169/198) in the trial conducted by Bolam and colleagues from November 1994 to May 1996.in Kathmandu, Nepal; 65%(242/375) and 55% (205/375) in the trial conducted by Usman and colleagues from September 2003 to March 2004 in urban Karachi in Pakistan; and 60% (228/378) and 39% (149/378) in the trial conducted by Usman and colleagues from November 2005 to August 2006 in rural Karachi in Pakistan. Combining data from the studies shows that facility-based education improves vaccination coverage (three trials, 1909 participants: RR 1.24, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.53, I2 = 74%) ( and ).

Figure 2. The effect of caregiver education on uptake of three doses of diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis containing vaccines among children.

Overall, the combined data show that education of parents improves vaccination coverage in low and middle-income countries (six trials; 4248 participants: RR 1.36, 95%CI 1.14 to 1.62; I2 = 65%) (). shows our confidence in this evidence. Evidence from randomised trials is considered of high certainty in the GRADE framework; but we downgraded this to moderate because three of the six studies had a high risk of bias.

Table 3. GRADE Summary of findings for the effects of caregiver education on vaccination coverage.

Discussion

The target of the Global Vaccine Action Plan was to achieve 90% national coverage with all vaccines on national vaccination schedules in all 194 countries by 2015Citation26. However, only 129 (66%) countries achieved this coverage target by 2014.Citation27 The ten countries with the largest numbers of un-immunised children are all low-income or lower-middle income countries.Citation27 There is thus an urgent need for effective interventions that would ensure equitable uptake of existing vaccines by people in all communities around the world.Citation26

In this systematic review, we have shown that caregiver education probably leads to substantial increases in childhood vaccination coverage. Although all six included trials were conducted in only three Asian countries (India, Nepal, and Pakistan), we have no reason to doubt the applicability of the evidence to other low and middle-income countries.

Only one study reported including information of adverse events following vaccination in the education sessions with parents.Citation17 We are, therefore, uncertain of the extent to which the information of adverse events following vaccination impacted the decision making of parents. An adverse event following vaccination is defined as “any untoward medical occurrence which follows vaccination and which does not necessarily have a causal relationship with the usage of the vaccine. The adverse event may be any unfavourable or unintended sign, abnormal laboratory finding, symptom, or disease”.Citation27 Such an adverse event maybe a vaccine product-related reaction, a reaction due to an error in administration, a reaction related to vaccine quality defect, a vaccination anxiety related reaction, or a coincidental event.Citation27

Ours is the most comprehensive and up to date review of randomised trial evidence of the effects of caregiver education on childhood vaccination coverage. However, our findings are consistent with those of related systematic reviews.Citation1,Citation29-31 Community-based evidence based discussions aimed at knowledge translation to community members may prove to be more effective than conventional health education strategies. However, the setting and scale of the targeted population may influence these findings. Kaufman and colleagues previously reviewed face-to-face interventions for informing or educating parents about early childhood vaccination, and reported that these interventions may have little to no impact on vaccination status or knowledge and understanding of vaccination.Citation29 The apparent difference in our conclusions may be because Kaufman and colleagues included studies from all country settings.Citation28 Therefore, provision of accurate vaccine information in communities and health facilities should be integrated into all childhood vaccination programmes in low and middle-income countries; accompanied by robust monitoring of the impact and use of data for action.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Contributions of authors

LAL and NVN contributed to screening, data extraction, analysis, and write up. CSW conceived the study, contributed to screening, data extraction, data analysis, and write up. NVN and CSW critically revised successive drafts of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the drafts and approved the final version of the review.

Acknowledgments

This work is sponsored partly by the South African Medical Research Council and the National Research Foundation of South Africa (Grant Numbers: 106035 and 108571).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Oyo-Ita A, Wiysonge CS, Oringanje C, Nwachukwu CE, Oduwole O, Meremikwu MM. Interventions for improving coverage of childhood immunisation in low- and middle-income countries. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016;10:CD008145. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008145.pub3.

- Chauke-Moagi BE, Mumba M. New vaccine introduction in the East and Southern African sub-region of the WHO African Region in the context of GIVS and MDGs. Vaccine. 2012;30:C3–C8. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.05.086. PMID:22939018.

- Levine OS, Bloom DE, Cherian T, de Quadros C, Sow S, Wecker J, Duclos P, Greenwood B. The future of immunisation policy, implementation, and financing. Lancet. 2011;378:439–48. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60406-6. PMID:21664676.

- Wiysonge CS, Uthman OA, Ndumbe PM, Hussey GD. Individual and contextual factors associated with low childhood immunisation coverage in sub-Saharan Africa: A multilevel analysis. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e37905. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0037905. PMID:22662247.

- Owais A, Hanif B, Siddiqui AR, Agha A, Zaidi AK. Does improving maternal knowledge of vaccines impact infant immunization rates? A community-based randomized-controlled trial in Karachi, Pakistan. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:239. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-11-239. PMID:21496343.

- Willis N, Hill S, Kaufman J, Lewin S, Kis-Rigo J, De Castro Freire SB, Bosch-Capblanch X, Glenton C, Lin V, Robinson P, et al. “Communicate to vaccinate”: the development of a taxonomy of communication interventions to improve routine childhood vaccination. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2013;13:23. doi:10.1186/1472-698X-13-23. PMID:23663327.

- Williams SE, Rothman RL, Offit PA, Schaffner W, Sullivan M, Edwards KM. A randomized trial to increase acceptance of childhood vaccines by vaccine-hesitant parents: a pilot study. Acad Pediatr. 2013;13:475–80. doi:10.1016/j.acap.2013.03.011. PMID:24011750.

- Gowda C, Schaffer SE, Kopec K, Markel A, Dempsey AF. Pilot study on the effects of individually tailored education for MMR vaccine-hesitant parents on MMR vaccination intention. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9:437–45. doi:10.4161/hv.22821. PMID:23291937.

- Burnett RJ, Larson HJ, Moloi MH, Tshatsinde EA, Meheus A, Paterson P, François G. Addressing public questioning and concerns about vaccination in South Africa: A guide for healthcare workers. Vaccine. 2012;30:C72–8. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.03.037. PMID:22939026.

- Coulter A, Ellins J. Effectiveness of strategies for informing, educating, and involving patients. BMJ. 2007;335:24–27. doi:10.1136/bmj.39246.581169.80. PMID:17615222.

- Williams N, Woodward H, Majeed A, Saxena S. Primary care strategies to improve childhood immunisation uptake in developed countries: systematic review. JRSM Short Rep. 2011;2:81. doi:10.1258/shorts.2011.011112. PMID:22046500.

- Lukusa LA, Adeniyi F, Wiysonge CS. Effects of interventions to inform or educate parents or caregivers about childhood vaccination in low and middle income countries. PROSPERO2014:CRD42014010141.[http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO_REBRANDING/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42014010141].

- Lukusa LA, Mbeye NN, Adeniyi FB, Wiysonge CS. Protocol for a systematic review of the effects of interventions to inform or educate caregivers about childhood vaccination in low and middle-income countries. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e008113. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008113. PMID:26169807.

- The World Bank Group. Data. Countries and Economies. Available from http://data.worldbank.org/country (accessed 16 May 2015).

- Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011.

- Wiysonge CS, Ngcobo NJ, Jeena PM, Madhi SA, Schoub BD, Hawkridge A, Shey MS, Hussey GD. Advances in childhood immunisation in South Africa where to now? Programme managers' views and evidence from systematic reviews. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:578. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-578. PMID:22849711.

- Andersson N, Cockcroft A, Ansari NM, Omer K, Baloch M, Ho Foster A, Shea B, Wells GA, Soberanis JL. Evidence-based discussion increases childhood vaccination uptake: a randomised cluster controlled trial of knowledge translation in Pakistan. BMC International Health and Human Rights. 2009;9(Suppl 1):S8. doi:10.1186/1472-698X-9-S1-S8. PMID:19828066.

- Bolam A, Manandhar DS, Shrestha P, Ellis M, Costello AM. The effects of postnatal health education for mothers on infant care and family planning practices in Nepal: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 1998;316:805–11. doi:10.1136/bmj.316.7134.805. PMID:9549449.

- Pandey P, Sehgal RA, Riboud M, Levine D, Goyal M. Informing Resource-Poor Populations and the Delivery of Entitled Health and Social Services in Rural India A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA. 2007;298:1867–75. doi:10.1001/jama.298.16.1867. PMID:17954538.

- Usman RH, Akhtarb S, Habibc F, Jehana I. Redesigned immunization card and center-based education to reduce childhood immunization dropouts in urban Pakistan: A randomized controlled trial. Vaccine. 2009;27:467–72. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.10.048. PMID:18996423.

- Usman RH, Rahbar HM, Kristensen S, Vermund SH, Kirby RS, Habib F, Chamot E. Randomized controlled trial to improve childhood immunization adherence in rural Pakistan: redesigned immunization card and maternal education. Trop Med Int Health. 2011;16:334–42. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02698.x. PMID:21159080.

- Abdul Rahman MA, Al-Dabbagh SA, Al-Habeeb QS. Health education and peer leaders' role in improving low vaccination coverage in Akre district, Kurdistan region, Iraq. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 2013;19:125–9. doi:10.26719/2013.19.2.125. PMID:23516821.

- Hu Y, Luo S, Tang X, Lou L, Chen Y, Guo J, Zhang B. Does introducing an immunization package of services for migrant children improve the coverage, service quality and understanding? An evidence from an intervention study among 1548 migrant children in eastern China. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:664. doi:10.1186/s12889-015-1998-5. PMID:26173803.

- Johri M, Chandra D, Kone GK, Dudeja S, Sylvestre MP, Sharma JK, et al. Interventions to increase immunisation coverage among children 12–23 months of age in India through participatory learning and community engagement: pilot study for a cluster randomised trial. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e007972. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007972. PMID:26384721.

- Keoprasith B, Kizuki M, Watanabe M, Takano T. The impact of community-based, workshop activities in multiple local dialects on the vaccination coverage, sanitary living and the health status of multiethnic populations in Lao PDR. Health Promotion International. 2013;28:453–65. doi:10.1093/heapro/das030. PMID:22773609.

- World Health Organization. Global Vaccine Action Plan 2011 – 2020. http://www.who.int/immunization/global_vaccine_action_plan/en/ (accessed 07 December 2015).

- Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunisation. 2015 Assessment report of the Global Vaccine Action Plan. http://www.who.int/immunization/global_vaccine_action_plan/SAGE_GVAP_Assessment_Report_2015_EN.pdf (accessed, 07 December 2015).

- World Health Organization. Causality assessment of an adverse event following immunization (AEFI): user manual for the revised WHO classification (Second edition). Geneva: WHO; 2018. http://www.who.int/vaccine_safety/publications/gvs_aefi/en/ (accessed, 07 March 2018)

- Kaufman J, Synnot A, Ryan R, Hill S, Horey D, Willis N, Lin V, Robinson P. Face to face interventions for informing or educating parents about early childhood vaccination. Cochrane Database syst Rev. 2013;31(5):CD010038.

- Saeterdal I, Lewin S, Austvoll-Dahlgren A, Glenton C, Munabi-Babigumira S. Interventions aimed at communities to inform and/or educate about early childhood vaccination. Cochrane Database syst Rev. 2014;19(11):CD010232.

- Harvey H, Reissland N, Mason J. Parental reminder, recall and educational interventions to improve early childhood immunisation uptake: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine. 2015;33:2862–80. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.085.

Appendix 1.

Search strategy for electronic databases

MEDLINE

CINAHL