ABSTRACT

Recently, China has attached great importance to promoting immunization, prompting the media, scholars, and public to focus on its coverage and efficacy. This study aimed to understand the factors influencing parental willingness to have their school-aged children vaccinated with quadrivalent influenza vaccines (QIVs). A cross-sectional study through face-to-face interviews was conducted between September and December 2018. Forty-four kindergartens and primary and junior high schools were randomly selected via stratified three-stage cluster sampling. Of 4,430 participants, 24.6% reported having heard of QIV and 24.2% reported having previously received information on QIV. Of these, 42.8% expressed willingness to obtain the QIV for their children. A junior college degree (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 1.447; 95% confidence interval [95% CI]: 1.202–1.742), higher influenza knowledge level (medium level, aOR = 1.150, 95% CI, 1.006–1.314; high level, aOR = 1.332, 95% CI, 1.045–1.697), and previous influenza information (aOR = 2.241; 95% CI, 1.604–3.130) were positively correlated with vaccination willingness. In contrast, no previous QIV-related information (aOR = 0.490; 95% CI, 0.418–0.575), no perceived susceptibility of children to influenza (aOR = 0.576; 95% CI, 0.489–0.680), fear of side effects (aOR = 0.599; 95% CI, 0.488–0.735), concern that vaccines need to be carefully administered (aOR = 0.728; 95% CI, 0.593–0.894), and mistrust of new vaccines (aOR = 0.730; 95% CI, 0.628–0.849) were pivotal barriers hindering parents from having their children vaccinated. This study provides baseline information for future immunization programs and delivery, with the ultimate goal of increasing vaccine uptake and minimizing school-wide influenza outbreaks.

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization, the annual incidence of seasonal influenza is 5–10% in adults and 20–30% in children. This results in 3–5 million severe cases globally, claiming an average of 290,000–650,000 lives per year.Citation1 Over the past few years, cases of human infection with new influenza viruses have been detected via the fast-developing influenza surveillance network in China.Citation2,Citation3 Annual seasonal vaccination is considered the most effective strategy to prevent influenza and its complications. Over 60 years of global vaccination practice and numerous studies have shown that influenza vaccines are safe and effective in preventing influenza and its complications. Vaccination reduces the spread of the virus as the first line of defense.Citation1,Citation4 Regarding vaccination coverage, a European study showed that influenza vaccine distribution in high-income countries (139.2/1000) is significantly higher than that in low- and middle-income countries (6.1/1000).Citation5 Based on presently available data, vaccination coverage in some developed countries falls between 60% and 70%, whereas for vulnerable groups (adults aged >65 years and health professionals), it peaks at >90%.Citation5,Citation6 In comparison, the influenza vaccine is a self-paid vaccine in China, and the annual uptake is extremely low at 2–3%.Citation7 Before 2018, trivalent influenza vaccine (TIV), including split virion and subunit and live-attenuated subtypes, was the only approved vaccine in China. On June 12, 2018, China’s Food and Drug Administration licensed the first quadrivalent influenza vaccine (QIV), co-produced by Hualan Bio and the Changsheng Bio-Technology Corporation, which was released nationwide in October 2018. QIV is immunogenic to the three strains shared in the TIV and has superior efficacy to the alternate B lineage (non-TIV lineage), with seroprotection rates after vaccination of 87.7% for subtype H1N1, 98.7% for subtype H3N2, 93.6% for subtype By, and 77.2% for subtype B.Citation8,Citation9 A budget impact analysis in Italy demonstrated that the QIV is a more cost-effective means for reducing the influenza burden than the TIV.Citation10

A systematic review in England demonstrated that the vaccine uptake in children was strongly associated with the following factors: perception that vaccines do not cause side effects, positive vaccine recommendations, and perception of fewer practical difficulties of vaccination.Citation11 After the inclusion of school-aged children in the national recommendations for influenza vaccination in the United States, a systematic review revealed several facilitators for parents to accept school-located influenza vaccination: belief in vaccine efficacy and influenza severity and susceptibility, perception of advantages of the school setting, and trust in vaccines.Citation12 Meanwhile, barriers include cost; concerns about vaccine safety, efficacy, and side effects; perception of barriers owning to the school setting; and distrust in vaccines.Citation12 In China, the reasons for undervaccination include a lack of public awareness of influenza and its vaccine, inaccessibility of vaccination services, and cost.Citation13–Citation15 Several studies investigating the correlation between parental willingness and vaccination coverage in children reveal that low levels of influenza vaccination uptake also correlate with perception and knowledge of the disease and vaccine, vaccine safety, side effects, and uncertainty of vaccine efficacy.Citation16–Citation19 Studies conducted in Singapore, Japan, Germany, and other countries have demonstrated that recommendations from pediatricians and schools can improve awareness and vaccination willingness.Citation20–Citation22 Understanding parents’ willingness to have their children vaccinated is essential in developing an effective immunization program and preventing school-wide influenza outbreaks.

As the largest province in Southern China, Guangdong has the greatest influenza disease burden. According to the China Information System for Disease Control and Prevention, there were 184,962 influenza cases in 2018, an increase of 66.8% over the number of influenza cases in 2017 (110,879 cases). The Chinese government is currently developing the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Greater Bay Area (also known as the Yuegang’ao Greater Bay Area or Greater Bay Area) as a world-class economic bay area and preventing and controlling infectious diseases plays a key role in accelerating this process. The Nanhai District, located in the center of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Greater Bay Area, had an increase of 67.9% in the number of influenza cases in 2018 (3,535 cases) compared to that in 2017 (2,106 cases). Given this increase, it is vital to understand parents’ attitudes toward vaccinating their children with the QIV. Moreover, as the QIV is a new vaccine, no previous studies have evaluated parental perceptions or factors influencing its use in children. Hence, we conducted this study to identify parents’ perceptions, knowledge, and attitudes toward influenza and the QIV in the Nanhai District, aiming to evaluate the factors associated with vaccination noncompliance and provide baseline information for future immunization programs and delivery.

Results

Parents’ willingness to accept QIV

Among the 4,430 participants who provided credible information in the questionnaires, 2,621 participants were female (59.2%) and 1,809 participants were male (40.8%), with an average age of 38.2 ± 9.1 years; 40.0% of participants were fathers; 56.7% were local residents; 59.8% had a secondary school degree or below; 24.2% reported that their children had been previously diagnosed with influenza; 42.8% expressed willingness to have their children vaccinated with the QIV (). Overall, participants who agreed with vaccination and those who disagreed shared similar demographics; participants with children attending kindergarten were more likely to accept the QIV for their children than participants with children attending primary school (odds ratio [OR] = 0.784; 95% CI, 0.671–0.916) and junior high school (OR = 0.814; 95% CI, 0.689–0.962).

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of participants and correlation with their willingness to vaccinate their children (N = 4430)

Awareness and knowledge of influenza and vaccination and their relationship with parents’ willingness to vaccinate their children

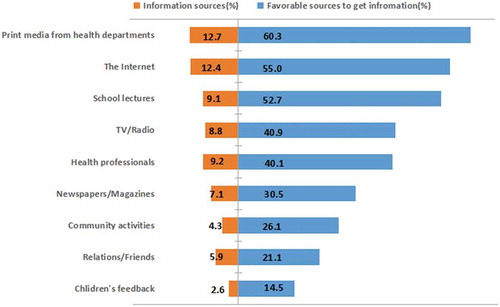

Overall, 95.2% of participants reported that they had heard of influenza and were interested in learning about the disease, including its modes of transmission, associated severe complications (including death), and identification of high-risk groups. Total of 83.8% of participants correctly answered the question concerning the modes of transmission. On the contrary, the majority had little knowledge of medications or vaccination for influenza, with an accuracy rate of only 25.1% (). The average score of influenza knowledge was 5.34 ± 2.53, with only 8.0% of participants having a high level of influenza knowledge (scoring 10 or 12). Exactly 24.6% of participants had heard of the QIV, and 24.2% had received information about the QIV. Print media from health departments (12.7%) and the Internet (12.4%) were the most common sources, followed by recommendations from health professionals (9.2%) and school lectures (9.1%). Similarly, the most cited sources by participants who preferred to receive additional information on the QIV were printed material from health departments, the Internet, and school lectures (). The univariate analysis showed that participants who previously heard of influenza (OR = 2.230; 95% CI, 1.631–3.049) and had a higher level of influenza knowledge (medium knowledge level, OR = 1.248, 95% CI, 1.102–1.413; high knowledge level, OR = 1.442, 95% CI, 1.149–1.810) were more likely to accept vaccination for their children (). Compared to participants who previously received information on the QIV, those who did not receive information (OR = 0.446; 95% CI, 0.383–0.519) or were uncertain (OR = 0.445; 95% CI, 0.379–0.522) were less likely to accept vaccination for their children ().

Table 2. Accuracy of influenza-related knowledge

Table 3. Analysis of parents’ perceptions and attitudes towards influenza and QIV and their willingness on vaccination in the future

Parents’ attitude and its relationship to their willingness to vaccinate their children

A majority of participants were concerned about the side effects after vaccination (84.9%). Other factors were uncertainty of its efficacy (82.4%), mistrust of the new vaccine (61.9%), and doubt of its effectiveness in preventing influenza (61.4%). Without adjusting for other factors, key factors associated with participants’ acceptability of the QIV included fear of side effects (OR = 0.412; 95% CI, 0.348–0.488), concern that the vaccine needs to be carefully administered (OR = 0.474; 95% CI, 0.399–0.556), mistrust of the new vaccine (OR = 0.516; 95% CI, 0.456–0.584), and uncertainty of its efficacy (OR = 0.521; 95% CI, 0.445–0.609) ().

Multivariable analysis

As shown in , the multivariable logistic regression model included all variables that showed extremely strong evidence of an effect on parents’ willingness to vaccinate their children. In particular, a junior college degree (aOR = 1.447; 95% CI, 1.202–1.742), a higher level of knowledge of influenza (medium knowledge level, aOR = 1.150, 95% CI, 1.006–1.314; high knowledge level, aOR = 1.332, 95% CI, 1.045–1.697), and previous information on influenza (aOR = 2.241; 95% CI, 1.604–3.130) were positively correlated with vaccination willingness. On the contrary, no previous QIV-related information (aOR = 0.490; 95% CI, 0.418–0.575), no perceived susceptibility of children to influenza (aOR = 0.576; 95% CI, 0.489–0.680), fear of side effects (aOR = 0.599; 95% CI, 0.488–0.735), concern that vaccines need to be carefully administered (aOR = 0.728; 95% CI, 0.593–0.894), and mistrust of the new vaccine (aOR = 0.730; 95% CI, 0.628–0.849) were associated with a lower vaccination willingness.

Table 4. Multivariable logistic regression analysis of the predictors for parents’ willingness to vaccinate their children in the future

Discussion

According to our literature review, this is the first worldwide study assessing awareness, attitude, and acceptability of the QIV of parents whose children are attending kindergarten or primary or junior high school. The most remarkable finding in our study was that 42.8% of parents were willing to have their children vaccinated with the QIV; most of the parents had poor knowledge of influenza, with 45.0% of parents’ scores indicating a low level of knowledge, and only 8.0% of parents were considered to have a high level of knowledge. Only 24.6% of parents reported previously receiving QIV-related information, which was not surprising as our study was conducted 1 month after the QIV was released and the vaccines remained out of stock in the study region. Our study also indicates that parents who had not previously received QIV-related information tended to refuse vaccination. This finding is consistent with those of other studies on vaccination, implying an urgent need for education on influenza in China.Citation23

Addressing parents’ vaccine hesitancy by guarantee policy and authoritative release

Based on our univariate analysis, the pivotal barrier hindering parents from vaccinating their children with QIV was that vaccination was not required by the government or schools (OR = 0.626; 95% CI, 0.550–0.713). In China, influenza vaccines are self-paid vaccines and can be administered only in designated hospitals. Although students are a susceptible population, experts in China have suggested that high schools, primary schools, and kindergartens in areas where conditions permit could launch vaccination campaigns proactively.Citation24 The Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Greater Bay Area, where the Nanhai District is located, has been identified as an economically developed region; thus, the government aims to implement policies that support free influenza vaccination or a vaccination subsidy scheme following practices in Beijing and Xinjiang.Citation7,Citation25 The government also aims to promote student vaccination by launching school-based vaccination programs, which have been proven effective in other countries including England and the United States.Citation12,Citation26

In our study, more than 80% of parents expressed concerns about side effects (84.9%) and vaccine safety (82.4%). Concern about side effects as a predominant barrier for parents to vaccinate their children is consistent with findings in other studies on vaccine acceptability.Citation12,Citation27,Citation28 More than 60% of participants were skeptical of new vaccines and doubted the efficacy of the QIV. A possible reason could be the Changchun Changsheng Vaccine Scandal in July 2018, when the Changchun Changsheng Biotechnology Corporation was found to have fabricated production records of freeze-dried rabies vaccines for human use. This was widely reported and broadcast via social media, thereby triggering a national uproar and serious mistrust of the vaccine among parents. Despite the government’s prompt and positive response, public concerns regarding vaccine safety have not yet been eliminated. If vaccination fails to be proven as credible, parents with vaccination hesitancy may delay or even refuse vaccination. This will result in the development of disease and potentially cause influenza outbreaks in schools. In response to vaccine hesitancy, interventions are best targeted at the population level as suggested by numerous experts. They believe that vaccine hesitancy can be minimized by the following measures: promoting transparency in policymaking before finalizing vaccination programs, providing health professionals and the public with up-to-date information on the rigorous vaccine testing and approval process, and diversifying post-marketing surveillance of vaccine-related incidents.Citation29

In our study, print media from health departments and the Internet were the most common vaccine-related information sources. Some studies have suggested that recommendations put forward by health professionals contribute to vaccination uptake.Citation27,Citation30 A study on influenza vaccine intervention in China also highlighted that 98% of elderly individuals reported being vaccinated following recommendations from health professionals.Citation14 In general, the public believe that health professionals are often the most reliable source of vaccination information.Citation31 Internet Plus represents the integration of the Internet with traditional industries, including health services, through open and shared platforms.Citation32 Considering the developmental benefits of Internet Plus, introducing online medical services and promoting vaccination via online social communication platforms (e.g., WeChat and Weibo) is an effective means for parents to receive positive information from credible sources. These can strengthen parents’ positive impressions of vaccines, thereby countering vaccine hesitancy and promoting influenza vaccination.

Developing a hospital-school-home intervention model to increase vaccination coverage

Apart from print media from health departments and the Internet, school lectures were also regarded as an essential and effective means to acquire credible information among parents, reflecting their admiration of schools. A previous study proved this intervention’s feasibility by indicating that communication with parents via special education contributes to their knowledge and trust in vaccination, thereby promoting vaccination compliance.Citation33 Accordingly, developing a hospital-school-home intervention model is a feasible measure involving physicians being invited to schools and to educate parents regarding influenza and vaccination, thereby improving parents’ access to QIV-related information and their children’s compliance with vaccination.

Enhancing clinical diagnoses and reports for raising the outbreak alert and early interventions

Another critical factor affecting vaccination acceptability is perceived susceptibility. More than 40% of parents believed that their children were healthy, not susceptible to influenza, and thus the influenza vaccine was unnecessary. Although there were only 3,535 confirmed influenza cases confirmed via laboratory tests or meeting the clinical case definition in the Nanhai District in 2018, the student surveillance system based on parents’ self-reporting of the child’s symptoms reveals that more than 69,000 students had an influenza-like illness (ILI).Citation34 This discrepancy may be attributed to clinicians diagnosing students with ILI as having an upper respiratory tract infection in the absence of an etiological diagnosis, thus misleading parents to consider that their children had not had influenza. In China, more than 85% of influenza outbreaks occurred in kindergartens, and primary and high schools.Citation35 In response, correcting parents’ misperceptions on the need for the influenza vaccine for children is vital. Additionally, improving clinical diagnoses and reports is significant for raising the alert level for school-wide influenza outbreaks and prompting the school and local Center for Disease Control and Prevention to perform early interventions.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, the timing of the study may have affected data collection as the data were collected shortly after the vaccine scandal; it takes time for parental perceptions and barriers toward vaccination to change. Second, the study was conducted shortly after the QIV was released, when only one domestic manufacturer produced the QIV and no imported vaccine was available. Thus, there was a serious shortage of the QIV, and the local health administration department had to cease advertising. Despite these limitations, this is the first known study to assess vaccine-related knowledge, perceptions, attitudes, and influential factors that may influence parents’ willingness to vaccinate their children. Furthermore, our data provide baseline information for future immunization programs and delivery, ultimately aiming to increase vaccine uptake and minimize school-wide influenza outbreaks. Lastly, the study did not consider whether parents themselves having received influenza vaccine can influence their willingness to vaccinate their children.

Conclusions

Our study indicates that information on influenza, QIV-related information, a junior college degree, and a high level of influenza knowledge are positive factors facilitating an increased willingness of parents to vaccinate their children. On the contrary, fear of side effects, mistrust of new vaccines, no perceived susceptibility of children to influenza, and concern that the vaccine needs to be carefully administered is associated with a decline in the willingness of parents to vaccinate their children. These findings highlight the need for intervention and programs to promote the uptake of influenza vaccination, specifically education, to address parents’ vaccine hesitancy and to correct misperceptions, including vaccine side effects and safety.

Materials and methods

Study population, recruitment, and sampling

A cross-sectional study, based on an anonymous questionnaire, was conducted with parents whose children were enrolled in schools located in the Nanhai District, Foshan, between September and December 2018. The Nanhai District, located in the center of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Greater Bay Area and adjacent to Guangzhou, is within the jurisdiction of Foshan, the third-largest city in Guangdong. The Nanhai District has a population of more than 3.2 million, accounting for 37.2% of the population in Foshan, and a GDP in 2017 reaching 378.19 million in US dollars, comprising 31.2% of the total GDP of Foshan. In 2018, the Nanhai District was selected as one of the country’s top 100 districts (ranked 11th) based on economic power, growth potential, green growth, people’s livelihoods, and efficiency.Citation36 Under the process of urbanization, the Nanhai District retains the unique characteristics of the Lingnan culture and is categorized as a typical rural-urban fringe. There are seven towns in the Nanhai District with 576 schools. A three-stage stratified random sampling method was used to classify the participants. In the first stage, schools in each town were divided into private and public schools and then into kindergartens, primary schools, and junior high schools. One school under each division was randomly selected using a random number table. In the second stage, using a random number table, two to three grades within each selected school were selected; then, one random class in each selected grade was chosen. In the third stage, all parents of those selected classes were invited to participate in our study. Overall, 44 schools and 4,500 parents provided their consent and participated in this study.

Data collection

The Nanhai Center for Disease Control and Prevention (NHCDC) issued a special work document through the Nanhai Health and Family Planning Bureau and Nanhai Education Bureau. It included a research protocol and information sheets providing further details about the study (purpose and survey process). Teachers were requested to distribute sealed envelopes containing questionnaires and consent forms and asked the children to hand the envelopes to their parents. Following the distribution, a month was allowed before the completed questionnaires and consent forms were collected. Community health service centers in corresponding towns examined each questionnaire’s quality (e.g., whether there is a noticeable logical error or more than 10% of the questions were left blank) and removed substandard questionnaires before sending them to the NHCDC. More than 85% of the questionnaires were returned within a week, and all were returned within the first 2 weeks. Overall, 4,500 parents provided consent to participate in this study, and 4,430 (98.4%) provided credible information. The anonymity of participants was maintained throughout the survey; thus, there was no follow-up among non-respondents.

Measures

We designed a 28-item self-administered questionnaire to assess participants’ perceptions, attitudes, and acceptability toward influenza and the QIV.

Main outcome

The main outcome was acceptability of the QIV, which was determined according to the dichotomous (yes/no) question: “The QIV has been licensed in China. Would you like to have your child(ren) vaccinated with QIV?” (0 = no, 1 = yes).

Sociodemographic information

We recorded participants’ age, sex, educational background, monthly household income, and medical history of influenza.

Awareness assessment

We used the following questions to measure awareness: “Have you heard of influenza?” and “Have you ever received information about the QIV?”

Knowledge assessment

We assessed the participants’ knowledge with six questions about the following: flu season, high-risk groups, modes of transmission, main symptoms, severity of disease, and medications for treatment. Although no standardized survey tools have been developed recently, these questions were designed on the basis of our pilot study and reviewed by a panel of experts. The score for each question was 2, and the maximum total score was 12. Participants were divided into three knowledge levels based on the total score: low (scored 0, 2, or 4), medium (scored 6 or 8), and high (scored 10 or 12). The question, “Have you ever received information about the QIV?”, was asked to examine whether participants had previously received any vaccine-related information.

Sources of information

Parents were asked whether they received the QIV information from any of the following nine sources and their preference for receiving information in the future: print media from health departments, the Internet, school lectures, television/radio, newspaper/magazine, health professionals, community activities, feedback from relatives/friends, and feedback from children. These were multiple-choice questions; thus, parents could select all options that applied.

Attitude assessment

Participants’ attitudes were assessed using the following six criteria: safety (“Are you concerned about the safety of the QIV?”), effectiveness (“Do you think that the QIV is effective in preventing your children from developing influenza?”), side effects (“Do you think that there are unknown side effects for the QIV?”), susceptibility (“Do you think your children could be infected with influenza?”), cost (“What do you think of the cost of the QIV?”), and accessibility (“Is it convenient for you to vaccinate your children?”).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis was conducted to determine participants’ demographic characteristics, awareness, perceptions, attitudes, and acceptability toward influenza and QIV. Univariate logistic regression analysis was used to explore factors associated with participants’ willingness to accept QIV, including sociodemographic information, influenza knowledge, QIV knowledge, and attitudes on vaccination. Variables with statistical significance were further analyzed through multivariate logistic regression to determine whether they were independent predictors. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 19.0. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Authors’ contributions

The study was designed by PB and ZY, with the assistance of WM, WL, and ZH. ZY and PB drafted the manuscript. WJ, ZP, and GH contributed to the field research. ZY, HY, and XM collected and analyzed the data. All authors assisted in reviewing and editing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (40.8 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all community health service centers, schools, and workers who participated in this study and assisted in questionnaire collection.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this paper can be accessed on the publisher’s website.

Additional information

Funding

References

- World Health Organization. Influenza (seasonal), fact sheet. 2018 Nov 6 [accessed 2019 Jan 9]. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs211/en/.

- Chen H, Yuan H, Gao R, Zhang J, Wang D, Xiong Y, Fan G, Yang F, Li X, Zhou J, et al. Clinical and epidemiological characteristics of a fatal case of avian influenza A H10N8 virus infection: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2014;383(9981):714–21. PMID: 24507376. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60111-2.

- World Health Organization. Human infection with avian influenza A (H7N4) virus-China. 2018 Feb 22 [accessed 2019 Jan 9]. https://www.who.int/csr/don/22-february-2018-ah7n4-china/en/.

- Thompson WW, Weintraub E, Dhankhar P, Cheng PY, Brammer L, Meltzer MI, Bresee JS, Shay DK. Estimates of US influenza-associated deaths made using four different methods. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2009;3(1):37–49. PMID: 19453440. doi:10.1111/j.1750-2659.2009.00073.x.

- Jorgensen P, Mereckiene J, Cotter S, Johansen K, Tsolova S, Brown C. How close are countries of the WHO European region to achieving the goal of vaccinating 75% of key risk groups against influenza? Results from national surveys on seasonal influenza vaccination programmers, 2008/2009 to 2014/2015. Vaccine. 2018;36(4):442–52. PMID: 29287683. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.12.019.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Flu vaccination coverage, United States, 2016–17 influenza season. Georgia (GA): Office of the Associate Director for Communication, Digital Media Branch, Division of Public Affairs; 2018 Jul28. [accessed 2019 Jan 9]. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/coverage-1617estimates.htm.

- Yang J, Atkins KE, Feng L, Pang M, Zheng Y, Liu X, Cowling BJ, Yu H. Seasonal influenza vaccination in China: landscape of diverse regional reimbursement policy, and budget impact analysis. Vaccine. 2016;34(47):5724–35. PMID: 27745951. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.10.013.

- Moa AM, Chughtai AA, Muscatello DJ, Turner RM, Maclntyre CR. Immunogenicity and safety of inactivated quadrivalent influenza vaccine in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Vaccine. 2016;34(35):4092–102. PMID: 27381642. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.06.064.

- Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. National Immunization Advisory Committee (NIAC) Technical Working Group (TWG), Influenza Vaccination TWG. Technical Guidelines for Seasonal Influenza Vaccination in China (2018–2019) (Full Edition). Report No.: [2018] 91. Beijing (China): Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention; 2018 [accessed 2019 Mar 15]. http://www.chinacdc.cn/jkzt/crb/xcrxjb/201809/W020180929303987156055.pdf.

- Pitrelli A. Introduction of a quadrivalent influenza vaccine in Italy: a budget impact analysis. J Prev Med Hyg. 2016;57(1):34–40. PMID: 27346938.

- Smith LE, Amlôt R, Weinman J, Yiend J, Rubin GJ. A systematic review of factors affecting vaccine uptake in young children. Vaccine. 2017;35(45):6059–69. PMID: 28974409. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.09.046.

- Kang GJ, Culp RK, Abbas KM. Facilitators and barriers of parental attitudes and beliefs toward school-located influenza vaccination in the United States: systematic review. Vaccine. 2017;35(16):1987–95. PMID: 28320592. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.03.014.

- LH B, XN H, Bo T, SX L, Liu Z, Pang ST, Jiang FC, Liu XC, Liu JC. Surveying the medical professionals’ knowledge, attitude and practice of influenza and influenza vaccine in Qingdao. Chin Health Serv Manag. 2015;32(6):474–76. In Chinese.

- Song Y, Zhang T, Chen L, Yi B, Hao X, Zhou S, Zhang R, Greene C. Increasing seasonal influenza vaccination among high risk groups in China: do community healthcare workers have a role to play? Vaccine. 2017;35(33):4060–63. PMID: 28668569. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.06.054.

- Ma X. Investigation of reasons and influence factors of unvaccinated influenza vaccines in more than 60 years old people live in Kelamayi, Xinjiang province, 2015. China Field Epidemiol Train Program Rep. 2017;16:31–39. In Chinese.

- Zhuang QY, Wong RX, Chen WMD, Guo XX. Knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding human papillomavirus vaccination among young women attending a tertiary institution in Singapore. SMJ. 2016;57(6):329–33. PMID: 27353611. doi:10.11622/smedj.2016108.

- Chan EY, Cheng CK, Tam GC, Huang Z, Lee PY. Willingness of future A/H7N9 influenza vaccine uptake: a cross-sectional study of Hong Kong community. Vaccine. 2015;33(38):4737–40. PMID: 26226564. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.07.046.

- Zhang J, While AE, Norman IJ. Seasonal influenza vaccination knowledge, risk perception, health beliefs and vaccination behaviours of nurses. Epidemiol Infect. 2012;140(9):1569–77. PMID: 22093804. doi:10.1017/S0950268811002214.

- Kim HW. Knowledge about human papillomavirus (HPV), and health beliefs and intention to recommend HPV vaccination for girls and boys among Korean health teachers. Vaccine. 2012;30(36):5327–34. PMID: 22749602. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.06.040.

- Low MSF, Tan H, Hartman M, Tam CC, Hoo C, Lim J, Chiow S, Lee S, Thng R, Cai M, et al. Parental perceptions of childhood seasonal influenza vaccination in Singapore: a cross-sectional survey. Vaccine. 2017;35(45):6096–102. PMID: 28958811. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.09.060.

- Boes L, Boedeker B, Schmich P, Wetzstein M, Wichmann O, Remschmidt C. Factors associated with parental acceptance of seasonal influenza vaccination for their children - a telephone survey in the adult population in Germany. Vaccine. 2017;35(30):3789–96. PMID: 28558985. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.05.015.

- Shono A, Kondo M. Factors associated with seasonal influenza vaccine uptake among children in Japan. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15(1):72. doi:10.1186/s12879-015-0821-3.

- Li T, Wang H, Lu Y, Li Q, Chen C, Wang D, Li M, Li Y, Lu J, Chen Z, et al. Willingness and influential factors of parents to vaccinate their children with novel inactivated enterovirus 71 vaccines in Guangzhou, China. Vaccine. 2018;36(26):3772–78. PMID: 29776754. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.05.054.

- Zheng JD, Peng ZB, Qin Y, Feng LZ, Li ZJ. Current situation and challenges on the implementation of prevention and control programs regarding the seasonal influenza, in China. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2018;39(8):1041–44. PMID: 30180425. In Chinese. doi:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2018.08.006.

- Pan Y, Wang Q, Yang P, Zhang L, Wu S, Zhang Y, Sun Y, Duan W, Ma C, Zhang M, et al. Influenza vaccination in preventing outbreaks in schools: a long-term ecological overview. Vaccine. 2017;35(51):7133–38. PMID: 29128383. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.10.096.

- Paterson P, Chantler T, Larson HJ. Reasons for non-vaccination: parental vaccine hesitancy and the childhood influenza vaccination school pilot programme in England. Vaccine. 2018;36(36):5397–401. PMID: 28818568. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.08.016.

- Alshammari TM, AlFehaid LS, AlFraih JK, Aljadhey HS. Health care professionals’ awareness of, knowledge about and attitude to influenza vaccination. Vaccine. 2014;32(45):5957–61. PMID: 25218193. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.08.061.

- Chao K. The improvement of Chinese second category vaccines supervision system from the perspective of supervision elements: based on a case study of the Shandong problematic vaccines incident in China. Saudi J Human Social Sci. 2016;1(3):88–92. doi:10.21276/sjhss.2016.1.3.3.

- Kumar D, Chandra R, Mathur M, Samdariya S, Kapoor N. Vaccine hesitancy: understanding better to address better. Isr J Health Policy Res. 2016;5:2. PMID: 26839681. doi:10.1186/s13584-016-0062-y.

- Yuen CYS, Fong DYK, Lee ILY, Chu S, Siu ES, Tarrant M. Prevalence and predictors of maternal seasonal influenza vaccination in Hong Kong. Vaccine. 2013;31(45):5281–88. PMID: 24016814. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.08.063.

- Peng ZB, Wang DY, Yang J, Yang P, Zhang YY, Chen J, Chen T, Zheng YM, Zheng JD, Jiang SQ, et al. Current situation and related policies on the implementation and promotion of influenza vaccination in China. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2018;39(8):1045–50. PMID: 30180426. In Chinese. doi:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2018.08.007.

- Wang Z, Chen C, Guo B, Yu Z, Zhou X. Internet plus in China. IT Prof. 2016;18(3):5–8. doi:10.1109/MITP.2016.47.

- Chow MYK, Danchin M, Willaby HW, Pemberton S, Leask J. Parental attitudes, beliefs, behaviours and concerns towards childhood vaccinations in Australia: a national online survey. Aust Fam Physician. 2017;46(3):145–51. PMID: 28260278.

- Foshan Student Health Surveillance System. Health surveillance management – morning check and sickness absence. [accessed 2019 Jan 09]. [intranet]. http://119.145.135.242/fsxsjkjh/kjzm/index-xs.html.

- Li M, Feng L, Cao Y, Peng Z, Yu H. Epidemiological characteristics of influenza outbreaks in China, 2005–2013. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2015;36(7):705–08. PMID: 26564698. In Chinese.

- The Paper. China’s top 100 districts: Nanshan, Shenzhen ranked the first, four districts in Qingdao are on the list. Qingdao (China): Qingdaofabu; 2018 Sep 25. [accessed 2019 April 30]. https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_2471791.