ABSTRACT

Simultaneous administration of different vaccines is a strategy to increase the possibility to receive vaccines at appropriate age, safely and effectively, reducing the number of sessions and allowing a more acceptable integration of new vaccines into National Immunization Programs (NIPs). Co-administration can be performed when there are specific indications in the Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) of the vaccines; but, in absence of these indications, the practice is possible if there are no specific contraindications nor scientific evidence to discourage simultaneous administration.

The aim of this work is to review the safety and efficacy of co-administration of the tetravalent measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella (MMRV) and the meningococcal C (Men C) conjugate vaccines after 12 months of age.

Several studies demonstrated that MMRV and Men C conjugate vaccines can be administered concomitantly without a negative impact on the safety and immunogenicity of either vaccines, inducing highly immunogenic responses.

Introduction

The co-administration of vaccines is proposed to reduce the number of vaccination sessions, increase compliance, and ensure optimal coverage. In particular, the tetravalent measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella (MMRV) and the monovalent or tetravalent meningococcal C (Men C or Men ACWY) conjugate vaccines are administered worldwide between 13 and 15 months of life, a period during which children are immunized against different infectious diseases. Most of the scientific studies focus the analysis mainly on co-administration between MMRV and tetravalent meningococcal conjugate vaccines.Citation1,Citation2 The aim of this work is to assess, through an updated literature search, the safety and efficacy of co-administration and to provide a focus on MMRV and Men C conjugate vaccine co-administration in this age group.

Background

The immunization programs of each country greatly vary depending on the local context (epidemiological, socio-economic, cultural) and, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations, on the most appropriate age for the administration of different vaccines.Citation3

Vaccination strategies adopted in childhood can require a high number of sessionsCitation4 and the fulfillment of the entire vaccination schedule can be challenging for newborns, parents and health professionals.Citation5

This phenomenon is even more evident with the development and introduction of new vaccines. This makes the vaccination schedule more complex due to the further increase in the number of injections and immunization sessions. The consequences of a complex schedule may be a low compliance to vaccination and a consequent reduction of vaccination coverage rates.Citation1

Simultaneous administration of different antigens can be a valid practice to counteract the above-mentioned issues; this opportunity finds its rationale in the combination of different antigens as well as in the co-administration of several vaccines in the same session.

These practices increase the possibility to receive age-appropriate vaccines in a timely manner, reducing the number of sessions and allowing a more acceptable integration of new vaccines into schedules.Citation4,Citation6,Citation7

A combined vaccine can be defined as a vaccine consisting of two or more antigens, ready to use or to be mixed immediately before administration. The goal is to protect against multiple infectious diseases or multiple strains of infectious agents that cause the same disease.Citation8,Citation9

Co-administration of vaccines is defined as the administration of more than one vaccine on the same day. These administrations should be performed in different anatomic sites.Citation9

The vaccine combination and co-administration provide an important means of vaccination strategies’ optimization in different countries.

The administration of combined vaccines and co-administration also brings with them some critical issues sometimes linked to a difficult acceptance by citizens. There are concerns about the possibility that too many vaccines overload the immune system, that the combined vaccines may be less effective and can cause a greater number of adverse reactions compared to the vaccines administered separately.Citation10,Citation11

Combined products reduce the number of injections and pain compared to repeated injections; on the other hand, they also reduce cumulative exposure to preservatives and stabilizers that are erroneously linked by hesitant parents to the onset of adverse reactions.Citation12,Citation13

Furthermore, co-administration reduces the number of visits and, therefore, decreases stress and discomfort for children and parents.Citation5

Combined vaccines are thoroughly tested before they are approved for marketing. The United States (US) Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) ensure that the new products are safe and effective. There is no evidence that combined vaccines increase the burden of the immune system, which instead is able to respond simultaneously to millions of antigens. In general, the combination of different antigens may or may not bring to an additive effect on reactogenicity but always within the limits required for the product to be approved.Citation14

According to recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), there are numerous vaccines that can be administered simultaneously in an effective and safe way.Citation9 Co-administration of different vaccines results to be immunogenic and well-tolerated as described in several papers.Citation15-Citation17 To cite some examples, Nakashima et al.Citation18 and Thompson et al.Citation19 concluded that co-administration of the quadrivalent influenza vaccine and the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPV23) and with the 13-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide conjugate vaccine (PCV13) respectively, is a safe and effective practice and does not lead to an increase in adverse reactions.Citation18,Citation19 Several authors evaluated the safety and immunogenicity of the quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine (Men ACWY) co-administered with common childhood vaccines, confirming good tolerability, elevated immunogenicity, and safety.Citation20–Citation24 Finally, with regard to the concomitant administration of meningococcal C conjugated vaccines (as tetravalent or monovalent vaccines) and MMRV, which will be further investigated in the course of this review, in recent studies performed by Durando et al.Citation5 and Klein et al.,Citation2 this co-administration appears to be well tolerated, without safety issues and with a good immune response for both vaccines.Citation2,Citation5

Public health impact of co-administration

Combined and co-administered vaccines optimize vaccination coverage thanks to the simplification of vaccination programs.Citation11,Citation25,Citation26

These elements guarantee a significant impact in terms of public health, specifically with the increase in vaccination coverage and the more efficient management of services.Citation9

Considering the higher spending on the purchase of more expensive vaccines that could initially discourage their use, the combination of vaccination saves economic resources thanks to the more profitable management of vaccination services, which will benefit from an easier management of appointments and potentially reduce registration errors.Citation27

There are no studies aimed at evaluating the impact assessment of co-administration in terms of economic savings, but some studies have been developed for combined vaccines, which mainly share the same principles of co-administration.

In 1999, Fendrick et al.Citation28 conducted a study to investigate the potential impact in terms of public health offered by the combination of a vaccine against Haemophilus Influenzae type b (Hib) and Hepatitis B vaccine (HBV) compared to the previous strategy with single vaccines. The obtained results were very encouraging especially regarding the impact on HBV compared to single vaccinations, estimating a reduction of cases of acute hepatitis, chronic hepatitis, and deaths of 53%, and a saving of resources of 4 million dollars. The results showed an increase in costs related to the immunization with this combined vaccine equal to 11 million dollars, but almost exclusively due to the increased coverage achieved.Citation28

In 2014, Zhou et al.Citation29 published a study to evaluate the direct and indirect cost savings offered by vaccinations through analysis of the data on the 2009 USA vaccine schedule and comparing it with a similar analysis dating back to 2001. Considering the increased use of combined vaccines in 2009, the researchers estimated an increase in the costs of immunization equal to about 4.7 billion US dollars. This estimation was due to higher costs related to combined vaccines in respect to single vaccines, and to the need to carry out more vaccination sessions in order to adhere to a more articulated schedule than the 2001 schedule.Citation29

However, the saving of direct and indirect costs related to the diseases and related to prevented complications has been estimated equal to almost 30 billion US dollars, mainly due to the increased vaccination coverage guaranteed by combination and co-administration.Citation30

Other advantages of combined vaccines are the simplification of the vaccination sessions and the enhanced compliance with the correct timing of the vaccination courses. Indeed, in 2017, Macartney et al.Citation31 studied this phenomenon in relation to the introduction of the MMRV combined vaccine in the national schedule compared to the previous, already combined, measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine. Taking into account the second dose of vaccine, MMRV allowed guaranteeing the correct timing in 13.5% more cases than the MMR vaccine. In addition, MMRV facilitated an increase by 4% coverage against varicella (first dose) in comparison to the monovalent vaccination.Citation31

Summary of product characteristics (SmPC): co-administration with or without specific indications

The SmPC is the most important regulatory document on a medicinal product in the European Union because it is part of the marketing authorization. It represents the basis of information for health-care professionals on how to use the medicinal product safely and effectively and it is frequently updated when new efficacy or safety data are available.

While the SmPC is a document intended primarily for health professionals (doctors, pharmacists, nurses), the Package Leaflet (PL) is a document intended for the patient/user and contains all the useful information for a safer and more correct use of the drug expressed in a clear and easy language.

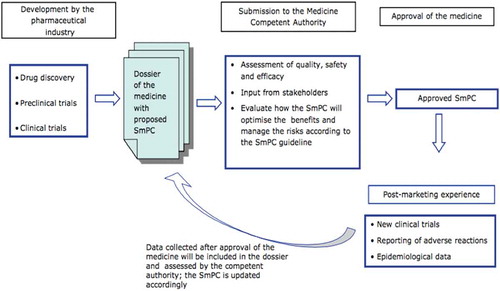

The preparation of the SmPC and the PL () is performed by referring to the document Corporate Core Data Sheet (CCDS), prepared by the marketing authorization holder and containing information concerning the safety in the narrow sense (Corporate Core Safety Information, CCSI), information on the indications, posology, pharmacology and all other information concerning the product.Citation32

Figure 1. Flow chart describing how documentation for SmPC is collected and prepared (Adapted from SmPC characteristics, EMA).

SmPC is a document with legal value and the contents of the PL and SmPC are established by law.Citation33

In the SmPC, information is presented following a predefined structure. One of the most relevant parts of SmPC is Section 4.1, that defines the pathological conditions for which the drug is intended. Moreover, it defines the use of the drug (therapeutic, preventive, diagnostic) and the limits of age for the drug use, according to the results of clinical trials.

From a medical-legal point of view, therapeutic indications established by SmPC should not debar the use of the drug/vaccine in other subjects. For example, hexavalent vaccines are administered “since 6 weeks of life”; therefore, they have no upper limit of use and this indication does not preclude its use in older age groups.Citation32

Moreover, the indication of use in the SmPC should not be confused with the term “recommended” which is applied to the NIPs. In fact, the term “recommended” is used on the basis of epidemiological evidence, suggesting a lower risk of disease in other age groups, but it does not relate to indication for use of the vaccine. For example, the monovalent Hib vaccine is not recommended above 5 years of age in the current NIPs; however, it is widely used also in adults with particular risk factors (i.e. asplenic subjects), for which it can represent a real life-saving intervention. There is no evidence that the administration of one, or more doses, of the Hib vaccine over 5 years entails risks of increased frequency and severity of adverse reactions.Citation34

Section 4.3 of the SmPC defines “the situations where the medicine must not be used for safety reasons”Citation32 and the patient populations who must not take the medicine.

The SmPC of a vaccine provides specific indications on co-administration, but for a number of reasons, when the SmPC is produced, it may not define all possible vaccine co-administration. Firstly, additional information, such as trials and post-marketing data on vaccine effectiveness, as well as safety data generated after large-scale use of the vaccine may be available after vaccine authorization. Secondly, decisions regarding vaccine use should also take into consideration a wide range of parameters including the age-specific pre-vaccine disease burden, public health needs, other health interventions, costs and cost-effectiveness studies, programmatic issues (such as existing schedules, impact on equity and policies) that are specific to the country or region, independently from the strict indications included in the SmPC. Thus, public health recommendations may differ across countries and WHO regions.Citation35

In addition, co-administration can be useful when there are no specific contraindications to co-administration and even if there are no specific indications in the SmPC. Moreover, sometimes there are scientific pieces of evidence to support the co-administration, which have not yet been included in the SmPC. Actually, international recommendations indicate that vaccines can be co-administered even in the absence of specific studies, unless there are specific pieces of evidence to avoid co-administration: the same situation is applied in the co-administration of all drugs.Citation36

For example, Meningococcus B and Rotavirus vaccines are co-administered in the absence of explicit specification in the SmPC but this practice is supported in the literature.Citation37

Co-administration of vaccines does not lead to an overload of the immune system; instead, it allows to obtain an antibody response for different diseases in less time.

As a matter of fact, since August 2017 the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunization in United Kingdom (UK) recommends during the first vaccination session (starting from the eighth week of life) the co-administration of Meningococcal B vaccine with Hexavalent, PCV-13 and Rotavirus vaccines.Citation38,Citation39

Also in Italy, the Ministry of Health recommends the co-administration of the Hexavalent, PCV-13 and Rotavirus vaccines to all newborns starting from the first vaccination session.Citation40

Off-label use of vaccines

Off-label use of vaccines or medicines has no standard definition. EMA defines off-label use as the situation where a medicine is intentionally used for a medical purpose not in accordance with the authorized product information.Citation41 Off-label use (called unlabeled indication) is defined by the FDA under the perspective of the health-care provider only (i.e. when a marketed drug is prescribed to treat a patient for an unlabeled indication).Citation42 For the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Drugs, off-label use of an approved drug refers to a use that is not included in the approved label.Citation43 On the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MEDRA) “off-label use” is defined as a practice of prescribing pharmaceuticals outside the scope of the drug’s approved label, most often concerning the drug’s indication.Citation44 For the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, “off-label” or “unlabelled” drug use occurs when a drug is used in a treatment regimen or patient population that is not included in the Notice of Compliance (NOC), and a drug is used for an indication other than those specifically included in the NOC.Citation45 Many off-label drug uses are effective, well documented in the peer-reviewed literature, and widely used.Citation35,Citation46–Citation48 In the chapter of the Practical Law of Company’s multi-jurisdictional guide to life sciences, L’Ecluse et al.Citation49 define off-label use the prescription or administration of an authorized medicinal product outside any of the terms of the marketing authorization, as reflected in the SmPC. This might include use for a different indication, at a different dosage (or dosage frequency) or in a different patient group (for example, children or pregnant women).Citation49 Therefore, off-label use can be defined as a prescription for a different indication, posology, age or population group from that included on the label.Citation35 The Italian legislation that regulates the off-label use of medicinal productsCitation50 indicates that the physician, when prescribing a drug, must follow the therapeutic indications and the ways of administration foreseen by the marketing authorization of the drug. However, the law allows using the drug outside the authorized indications if there are pieces of evidence documented in the literature and in the absence of better therapeutic alternatives. The off-label use of drugs exposes the patient to potential risks, considering that their efficacy and safety have been evaluated in different populations. From a medical/legal perspective, in 2017 the law n.24 “Provisions on professional liability of health personnel” was issued in Italy. This law shows that there is no medical liability when following established guidelines, such as the National Immunization Plan or the recommendations of scientific societies.Citation51

Immunogenicity and safety of co-administration of MMRV and meningococcal C conjugate vaccines

MMRV vaccines available in Europe are live attenuated tetravalent vaccines for the prevention of measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella (chickenpox) and they are licensed since 2005.Citation52,Citation53

In the scientific literature, the efficacy of individual components of the MMRV vaccine has been established previously.Citation10,Citation54–Citation58 MMRV vaccine had similar immunogenicity and overall safety profiles as MMR vaccine administered with or without varicella vaccine.Citation59,Citation60

The vaccines available in Europe for the immunization of children toward Meningococcus C are conjugate vaccines, as monovalent and tetravalent ACWY.Citation61–Citation67

The safety and the immunogenicity of meningococcal conjugate vaccines had been clearly evaluated in the literature.Citation22,Citation23,Citation68–Citation72

In most European countries, both the meningococcal conjugate and MMRV (or MMR+V) vaccines are recommended at around 13−15 months of age ().Citation38

Table 1. Recommended vaccinations in Europe for meningococcal C, Measles-Mumps-Rubella and Varicella vaccines (Adapted from European Center for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC)-Vaccine Scheduler: https://vaccine-schedule.ecdc.europa.eu/).

Some international studies demonstrated the advantages of vaccinations administered in the same visit, such as an increase in vaccination coverage, an increase in compliance with the entire vaccination course and the respect of the correct timing.Citation9,Citation11,Citation25,Citation26

Kurosky et al.Citation73 show how the combination of vaccines has considerably increased adherence to the complete vaccination course compared to what happens with the administration of monovalent vaccines. For example, as regards MMR vaccination, compliance with the timing of the vaccination course in those who received the combined vaccine was significantly higher (81.4%) compared to those who received the single vaccines (63.4%).Citation73

The considerations that emerge from these studies can also be made for the co-administration of MMRV and meningococcal vaccines, although at present there are no specific studies on the subject in the literature. To our knowledge, there are few studies on the co-administration of monovalent Men C conjugate vaccines and MMRV vaccines, while in the international scientific literature, some studies have evaluated co-administration of Men ACWY conjugate vaccine with MMRV vaccine.Citation1,Citation2,Citation23

A study by Vesikari et al.Citation1 showed that the quadrivalent Men ACWY conjugate vaccine can be co-administered with the MMRV vaccine between 12 and 23 months of age without affecting the immunogenicity or safety profiles of either vaccine. The occurrence of fever in the groups of children vaccinated with Men ACWY conjugate and MMRV versus MMRV alone was within the same range.Citation1

Actually, the co-administration of meningococcal conjugate vaccines does not affect the fever pattern, which is probably induced by the MMRV vaccine. Indeed, the prevalence of fever in both groups peaked between 4 and 10 days after vaccination with MMRV, in line with the known timing of fever in association with MMRV vaccines.Citation74

Similarly, Klein et al.Citation2 evaluated the safety in subjects who received Men ACWY conjugate vaccine and MMRV vaccine compared with those who received the MMRV vaccine alone. The study enrolled three groups of healthy children aged 7–9 months and 12 months. The first two groups included children aged from 7 to 9 months who received Men ACWY-CRM at 7–9 months either alone (group 2) or with MMRV at 12 months (group 1). A third group (group 3) was simultaneously enrolled at 12 months, receiving only MMRV.

Local reactogenicity was similar between the different groups. As to systemic reactions, children vaccinated with conjugate Men ACWY and MMRV compared with subjects who received Men ACWY conjugate vaccine alone experienced slightly higher rates of severe reactions during the 7 days of the period of follow-up, including fever; however, they had similar or lower rates of severe systemic reactions than those who received MMRV vaccine alone.

Furthermore, it was noted that within 7 days after vaccination, in the subjects who received conjugate Men ACWY and MMRV vaccines concomitantly, there were fewer febrile episodes compared to the group that received MMRV alone.Citation2

Instead, Durando et al.Citation5 reported that the occurrence of fever and rash in the Men C + MMRV and MMRV groups was within the same range.Citation5

Also, Vesikari et al.Citation1 reported no significant differences were found in the presentation of adverse events between the Men ACWY + MMRV and MMRV groups alone.Citation1

These studies demonstrated that Men ACWY conjugate vaccine can be administered in co-administration with MMRV vaccine at about 12 months of age, without a negative impact on the safety of both vaccines, and induced highly immunogenic responses against all four serogroups.Citation2,Citation23

In the same way, in the study by Scott et al.Citation54 co-administration of MMRV vaccine with a tetravalent Men ACWY conjugate vaccine in infants aged 12 months was associated with robust immune responses to all strains of both vaccines.Citation54

In an open-label multicenter trial, 1,014 children vaccinated with MMRV and conjugated Men ACWY vaccines and 616 children vaccinated with MMRV alone were analyzed. This analysis showed that the simultaneous administration of Men ACWY-CRM with MMRV at 12 months is well tolerated and without safety problems. The antibody responses to all vaccine components met the non-inferiority criteria following the administration of the meningococcal conjugate vaccine administered alone or co-administered with MMRV.Citation2

To date, the study of Durando et al.Citation5 conducted in Italy is the only one to prove the immunogenicity and safety of co-administration of a MMRV vaccine with a monovalent Men C conjugate vaccine.

The vaccines used in the study were a single dose (0.5 ml) of MMRV vaccine, Priorix-TetraTM, (GSK, Belgium) and a single dose (0.5 ml) of Men C CRM-197 conjugated vaccine, Meningitec (Nuron Biotech). In the study, 716 children between 13 and 15 months of age were enrolled. The bactericidal activity (rSBA- Men C: anti-meningococcal serogroup activity, cutoff: P ≥ 1:8) in groups of toddlers vaccinated with MMRV and Men C conjugate vaccines and Men C conjugate vaccine alone was 98.3% (95% CI 96–99.4 CI) and 99.3% (95%CI 96.2–100 CI), respectively. Antibody titers against single antigens of the MMRV vaccine, measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA), had the same protective values when co-administered with Men C conjugate vaccine or when given separately. The immune responses elicited by co-administered MMRV and Men C conjugate vaccines were high in all groups and non-inferior to those elicited by either MMRV or Men C conjugate vaccines alone. Regarding the safety profile, the percentages of toddlers who developed fever during the post-vaccination period (i.e. 43 days) were similar and likely due to the MMRV vaccine (64.9% in the group of subjects vaccinated with MMRV and conjugate Men C, 64.4% in subjects vaccinated with MMRV alone, and 37.4% in the group vaccinated with conjugate Men C alone). Indeed, the characteristic peak of fever at 5–12 days post MMRV vaccination was observed in both the MMRV/conjugate Men C and MMRV groups.Citation5 In addition to the positive data reported in the literature on co-administration of MMRV and quadrivalent meningococcus conjugate vaccines, also the co-administration of MMRV and Men C conjugate vaccines is possible and effective and does not affect the safety and immunogenicity of the respective vaccines.

Guidelines

The international guidelines on good practices to be implemented in the vaccination area give a consensus on the co-administration of vaccines. Regarding the co-administration of MMRV and meningococcal conjugate vaccines, there are specific indications in the SmPC for one of the two MMRV vaccines. The most accepted opinion regarding co-administration is summarized in the Pink Book where the following indications of the ACIP are reported: “simultaneously routine administration of all age-appropriate doses of vaccines is recommended for children for whom no specific contraindications exist at the time of the visit”.Citation36

The same ACIP guidelines, in the “Vaccine Administration” section, recommend performing vaccinations in the same session using separate anatomical sites, documenting for each patient in which place a specific vaccine has been injected. As a good clinical practice, it is also suggested to create an anatomical reference map for professionals in order to know where to administer a specific vaccine. If it is necessary to simultaneously administer more than two vaccines in the same site, it is a good practice to distance the injections by at least 1 inch (about 2.5 cm) to be able to identify and distinguish any local reactions.Citation9

The Immunization Book of the New Zealand Ministry of Health, revised in March 2018, encourages the simultaneous administration of vaccinations in order to reduce immunization sessions. In particular, this practice is suggested in the 15th month of life when the New Zealand vaccination schedule foresees the administration of four vaccinations (MMR, Varicella, PCV, Hib) that, according to the same guidelines, should be performed simultaneously in four distinct anatomical sites.Citation75

In addition, the guidelines of the Public Health Agency of Canada, updated in May 2017, suggest to implement co-administration, every time multiple vaccinations are provided for the schedule. This practice is considered always possible using different inactivated vaccines, as well as administering inactivated vaccines with live attenuated viral vaccines, as in the case of meningococcal conjugated vaccines and MMRV.Citation76

In the Green Book, the guidelines of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) of the UK are reported, updated in August 2017, which recommend the simultaneous administration between inactivated vaccines or inactivated vaccines with live attenuated ones as always possible.Citation77 In Italy, the 5th edition of the “Guide to contraindications to vaccinations”Citation78 published in March 2018 by the Ministry of Health and the High Health Council states that vaccinations can be safely administered in the same immunization session, maintaining a high immunogenicity against each antigen and helping to increase the successful completion of the vaccination courses. Co-administration of MMRV and meningococcal conjugated vaccines is therefore always possible, except for specific contraindications related to individual vaccinations. The only co-administration linked to MMRV, which should be avoided is the one with yellow fever vaccine because a lower immune response to mumps, rubella and yellow fever has been documented.Citation78 In Italy, the last edition of the “Vaccination Calendar for Life” (2019 edition), endorsed by four Scientific Societies (Italian Society of Hygiene, Preventive Medicine and Public Health – SItI, Italian Federation of Family Pediatricians – FIMP, Italian Federation of General Practitioners – FIMMG, and Italian Society of Pediatrics – SIP), supports co-administration of MMRV with monovalent meningococcal C conjugate vaccine. In the notes on the co-administrations of MMRV, it is suggested: “Administration of MMR or MMRV is possible in association with conjugate meningococcus C, meningococcus quadrivalent (ACWY) or meningococcus B vaccines.Citation79

The same recommendation is reported in the Italian NIP 2017–2019, in order to provide a rapid protection against many antigens simultaneously.Citation40,Citation79

Conclusions

Co-administration, and the use of combined vaccines, can be considered as one of the best approaches to reach high vaccination coverage rates, and to guarantee the objectives of the immunization program, ensuring immunogenicity and safety. Furthermore, co-administration allows to obtain a greater compliance, a reduction of costs, a simplification of operational procedures, and the possibility of adopting new vaccines. As a matter of fact, the addition of varicella to MMR vaccines has had a documented positive carry-over effect on varicella coverage.Citation61 Based on clinical trials, co-administration of MMRV vaccine with other routine childhood vaccinations does not impact significantly on either the immunogenicity of co-administered vaccines or the safety profile of MMRV.Citation54 In particular, the co-administration of MMRV and meningococcal C conjugate vaccines is not contraindicated, it is supported in the literature and recommended in the guidelines of international health authorities. Therefore, its application is desirable in a public health context in order to increase the current immunization coverage rates. The achievement of vaccination coverages to meet individual protection and public health prevention goals for both MMRV and meningococcal C conjugate vaccines is considered very important for infants >1 year. In conclusion, according to the collected evidence, the lack of specific indications for co-administration of these two types of vaccines on the SmPC should not represent a barrier and should be recognized in all countries in order to support health-care workers to use it as a good and safe practice.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No conflict of interest to declare

References

- Vesikari T, Karvonen A, Bianco V, Van der Wielen M, Miller J. Tetravalent meningococcal serogroups A, C, W-135 and Y conjugate vaccine is well tolerated and immunogenic when co-administered with measles–mumps–rubella–varicella vaccine during the second year of life: an open, randomized controlled trial. Vaccine. 2011;29(25):4274–84. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.03.043.

- Klein NP, Shepard J, Bedell L, Odrljin T, Dull P. Immunogenicity and safety of a quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine administered concomitantly with measles, mumps, rubella, varicella vaccine in healthy toddlers. Vaccine. 2012;30(26):3929–36. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.03.080.

- Masters NB, Wagner AL, Carlson BF, Boulton ML. Vaccination timeliness and co-administration among Kenyan children. Vaccine. 2018;36(11):1353–60. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.02.001.

- Giammanco G, Moiraghi A, Zotti C, Pignato S, Li Volti S, Giammanco A, Soncini R. Safety and immunogenicity of a combined diphtheria-tetanus-acellular pertussis-hepatitis B vaccine administered according to two different primary vaccination schedules. Multicenter working group. Vaccine. 1998;16(7):722–26. doi:10.1016/s0264-410x(97)00250-8.

- Durando P, Esposito S, Bona G, Cuccia M, Desole MG, Ferrera G, Gabutti G, Pellegrino A, Salvini F, Henry O, et al. The immunogenicity and safety of a tetravalent measles-mumps-rubella-varicella vaccine when co-administered with conjugated meningococcal C vaccine to healthy children: A phase IIIb, randomized, multi-center study in Italy. Vaccine. 2016;34(36):4278–84. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.07.009.

- Findlow H, Borrow R. Interactions of conjugate vaccines and co-administered vaccines. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12(1):226–30. doi:10.1080/21645515.2015.1091908.

- Eskola J, Ölander R-M, Hovi T, Litmanen L, Peltola S, Käyhty H. Randomised trial of the effect of co-administration with acellular pertussis DTP vaccine on immunogenicity of Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccine. Lancet. 1996;348(9043):1688–92. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(96)04356-5.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Expert committee on biological standardization. Recommendations to assure the quality, safety and efficacy of DT-based combined vaccines; Technical Report Series No. 980, Annex 6; 2014. [accessed 2019 Sep 4]. https://www.who.int/biologicals/WHO_TRS_980_WEB.pdf.

- Kroger AT, Duchin J, Vázquez M General best practice guidelines for immunization. Best Practices Guidance of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). [ accessed 2019 Sep. 4]. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/recs/storage/toolkit/default.html.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Marin M, Broder KR, Temte JL, Snider DE, Seward JF. Use of combination Measles, Mumps, Rubella, and Varicella Vaccine. [accessed 2019 Sept]. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5903a1.htm.

- Anh DD, Van Der Meeren O, Karkada N, Assudani D, Yu T-W, Han HH. Safety and reactogenicity of the combined diphtheria-tetanus-acellular pertussis-inactivated poliovirus- Haemophilus influenzae type b (DTPa-IPV/Hib) vaccine in healthy Vietnamese toddlers: an open-label, phase III study. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12(3):655–57. doi:10.1080/21645515.2015.1084451.

- Halsey NA. Combination vaccines: defining and addressing current safety concerns. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33(Suppl 4):S312–8. doi:10.1086/322567.

- Skibinski D, Baudner B, Singh M, O′Hagan DT. Combination vaccines. J Glob Infect Dis. 2011;3(1):63. doi:10.4103/0974-777X.77298.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Vaccine safety basics combination vaccines. [ accessed 2019 Sep 4]. https://vaccine-safety-training.org/combination-vaccines.html.

- Giammanco G, Li Volti S, Mauro L, Bilancia GG, Salemi I, Barone P, Musumeci S. Immune response to simultaneous administration of a recombinant DNA hepatitis B vaccine and multiple compulsory vaccines in infancy. Vaccine. 1991;9(10):747–50. doi:10.1016/0264-410x(91)90291-d.

- Arguedas A, Soley C, Loaiza C, Rincon G, Guevara S, Perez A, Porras W, Alvarado O, Aguilar L, Abdelnour A, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of one dose of MenACWY-CRM, an investigational quadrivalent meningococcal glycoconjugate vaccine, when administered to adolescents concomitantly or sequentially with Tdap and HPV vaccines. Vaccine. 2010;28(18):3171–79. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.02.045.

- Klein NP, Abu-Elyazeed R, Baine Y, Cheuvart B, Silerova M, Mesaros N. Immunogenicity and safety of the Haemophilus influenzae type b and Neisseria meningitidis serogroups C and Y-tetanus toxoid conjugate vaccine co-administered with human rotavirus, hepatitis A and 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccines: results from a phase III, randomized, multicenter study in infants. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(2):327–38. doi:10.1080/21645515.2018.1526586.

- Nakashima K, Aoshima M, Ohfuji S, Yamawaki S, Nemoto M, Hasegawa S, Noma S, Misawa M, Hosokawa N, Yaegashi M, et al. Immunogenicity of simultaneous versus sequential administration of a 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine and a quadrivalent influenza vaccine in older individuals: A randomized, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14(8):1923–30. doi:10.1080/21645515.2018.1455476.

- Thompson AR, Klein NP, Downey HJ, Patterson S, Sundaraiyer V, Watson W, Clarke K, Jansen K, Sebastian S, Gruber WC, et al. Coadministration of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate and quadrivalent inactivated influenza vaccines in adults previously immunized with polysaccharide pneumococcal vaccine 23: a randomized clinical trial. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(2):444–51. doi:10.1080/21645515.2018.1533777.

- Macias Parra M, Gentile A, Vazquez Narvaez JA, Capdevila A, Minguez A, Carrascal M, Willemsen A, Bhusal C, Toneatto D. Immunogenicity and safety of the 4CMenB and MenACWY-CRM meningococcal vaccines administered concomitantly in infants: A phase 3b, randomized controlled trial. Vaccine. 2018;36(50):7609–17. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.10.096.

- Dbaibo G, Tinoco Favila JC, Traskine M, Jastorff A. Van der Wielen M. Immunogenicity and safety of MenACWY-TT, a meningococcal conjugate vaccine, co-administered with routine childhood vaccine in healthy infants: A phase III, randomized study. Vaccine. 2018;36(28):4102–11. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.05.046.

- Klein NP, Reisinger KS, Johnston W, Odrljin T, Gill CJ, Bedell L, Dull P. Safety and immunogenicity of a novel quadrivalent Meningococcal CRM-conjugate vaccine given concomitantly with routine vaccinations in infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31(1):64–71. doi:10.1097/INF.0b013e31823dce5c.

- Nolan TM, Nissen MD, Naz A, Shepard J, Bedell L, Hohenboken M, Odrljin T, Dull PM. Immunogenicity and safety of a CRM-conjugated meningococcal ACWY vaccine administered concomitantly with routine vaccines starting at 2 months of age. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014;10(2):280–89. doi:10.4161/hv.27051.

- Gasparini R, Tregnaghi M, Keshavan P, Ypma E, Han L, Smolenov I. Safety and immunogenicity of a quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine and commonly administered vaccines after co-administration. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2015;35(1):1. doi:10.1097/INF.0000000000000930.

- Marshall GS, Happe LE, Lunacsek OE, Szymanski MD, Woods CR, Zahn M, Russell A. Use of combination vaccines is associated with improved coverage rates. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26(6):496–500. doi:10.1097/INF.0b013e31805d7f17.

- Alberer M, Burchard G, Jelinek T, Reisinger E, Beran J, Meyer S, Forleo-Neto E, Gniel D, Dagnew AF, Arora AK. Co-administration of a meningococcal glycoconjugate ACWY vaccine with travel vaccines: A randomized, open-label, multi-center study. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2014;12(5):485–93. doi:10.1016/j.tmaid.2014.04.011.

- Koslap-Petraco MB, Judelsohn RG. Societal impact of combination vaccines: experiences of physicians, nurses, and parents. J Pediatr Heal Care. 2008;22(5):300–09. doi:10.1016/j.pedhc.2007.09.004.

- Fendrick AM, Lee JH, LaBarge C, Glick HA. Clinical and economic impact of a combination Haemophilus influenzae and hepatitis B vaccine: estimating cost-effectiveness using decision analysis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(2):126–36. [accessed 2019 Sep 4]. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9988242.

- Zhou F, Santoli J, Messonnier ML, Yusuf HR, Shefer A, Chu SY, Rodewald L, Harpaz R. Economic evaluation of the 7-vaccine routine childhood immunization schedule in the United States, 2001. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(12):1136. doi:10.1001/archpedi.159.12.1136.

- Zhou F, Shefer A, Wenger J, Messonnier M, Wang LY, Lopez A, Moore M, Murphy TV, Cortese M, Rodewald L. Economic evaluation of the routine childhood immunization program in the United States, 2009. Pediatrics. 2014;133(4):577–85. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-0698.

- Macartney K, Gidding HF, Trinh L, Wang H, Dey A, Hull B, Orr K, McRae J, Richmond P, Gold M, et al. Evaluation of combination Measles-Mumps-Rubella-Varicella Vaccine introduction in Australia. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(10):992. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.1965.

- Summary of Product Characteristics Advisory Group. An agency of European Union – guideline of summary of product characteristics - European medicines agency- science medicines health. [ accessed 2019 Sep 4]. https://ec.europa.eu/health//sites/health/files/files/eudralex/vol-2/c/smpc_guideline_rev2_en.pdf.

- President of the Italian Republic. Legislative Decree April 24, 2006, n° 219 Implementation of EU Directive 2001/83/EC (and subsequent amending directives) relative to a community code concerning medicinal products for human use, as well as of EU Directive 2003/94/EC. [ accessed 2019 Sep 4]. https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2006/06/21/006G0237/sg.

- Rubin LG, Levin MJ, Ljungman P, Davies EG, Avery R, Tomblyn M, Bousvaros A, Dhanireddy S, Sung L, Keyserling H, et al. 2013 IDSA clinical practice guideline for vaccination of the immunocompromised host. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(3):e44–e100. doi:10.1093/cid/cit684.

- Neels P, Southern J, Abramson J, Duclos P, Hombach J, Marti M, Fitzgerald-Husek A, Fournier-Caruana J, Hanquet G. Off-label use of vaccines. Vaccine. 2017;35(18):2329–37. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.02.056.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Epidemiology and prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases. General recommendations on immunization. Simultaneus and Non simultaneus Administration. [ accessed 2019 September 4]. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/chapters.html.

- O’Ryan M, Stoddard J, Toneatto D, Wassil J, Dull PM. A multi-component meningococcal serogroup B vaccine (4CMenB): the clinical development program. Drugs. 2014;74(1):15–30. doi:10.1007/s40265-013-0155-7.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Immunisation and vaccines -Vaccination schedules for individual European countries and specific age groups. [ accessed 2019 Sep 4]. https://vaccine-schedule.ecdc.europa.eu/.

- GOV.UK Public Health England. The complete routine immunisation schedule from autumn 2018 Ref: PHE gateway number 2018450. [ accessed 2019 Sep 4]. https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/immunisation.

- Ministry of Health. National Vaccine Prevention Plan (PNPV) 2017-2019. [ accessed 2019 Sep 4]. https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2017/02/18/17A01195/sg.

- European Commission Directorate. Off-label use of medicinal products. [ accessed 2019 Sep 5]. http://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/files/documents/2017_02_28_final_study_report_on_off-.

- “Off-Label” and Investigational Use Of Marketed Drugs. Biologics, and medical devices. [ accessed 2019 Sep 5]. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/label-and-investigational-use-marketed-drugs-biologics-and-medical-devices.

- Committee On Drugs. Off-Label use of drugs in children. Pediatrics. 2014;110(1 pt 1):181–83. doi:10.1542/peds.110.1.181.

- Revelle P. Use of MedDRA: focus on the new scope of adverse scope of adverse event reporting. MSSO Presentations 2012. Conference/meeting 29 November 2012, Silver Spring, MD. [ accessed Sep 5, 2019]. https://www.meddra.org/sites/default/files/page/documents_insert/revelle_icsr_info_day_nov_2012_final.pdf.

- Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) Tools. Off-Label use of drugs. Questions and answers about the off-label use of drugs for health care providers. What does off-label mean?. [ accessed 2019 Sep 5]. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-.

- Tseng HF, Sy LS, Qian L, Marcy SM, Jackson LA, Glanz J, Nordin J, Baxter R, Naleway A, Donahue J, et al. Safety of a tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis vaccine when used off-label in an elderly population. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(3):315–21. doi:10.1093/cid/cis871.

- McGrath LJ, Brookhart MA. On-label and off-label use of high-dose influenza vaccine in the United States, 2010–2012. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2015;11(3):537–44. doi:10.1080/21645515.2015.1011026.

- Daskalaki I, Spain CV, Long SS, Watson B. Implementation of rotavirus immunization in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: high levels of vaccine ineligibility and off-label use. Pediatrics. 2008;122(1):e33–e38. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-2464.

- L’Ecluse P, Longeval C, T’Syen K, Bael, Bellis V. Off-label use of medicinal products and product liability. https://content.next.westlaw.com/8-525-5657?transitionType=Default&contextData=(sc.Default)&__lrTS=20190402003211431&firstPage=true&bhcp=1.

- President of the Italian Republic. Legislative Decree, February 17,1998, N. 23, converted, with amendments, in Law, Apri 8, 1998, No. 94 paragraph 2, article 3, so-called “Di Bella Law”. [ accessed 2019 Sep 4]. https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/1998/05/08/098A3335/sg.

- President of the Italian Republic. LAW March 8, 2017, No. 24 Provisions on the safety of care and the person assisted, as well as on the professional responsibility of the operators of the health professions. Official Journal of Italian Republic. [ accessed 2019 Sep 4]. https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2017/03/17/17G00041/sg.

- European Agency of Medicines. ProQuad: EPAR-product information. [ accessed 2019 Sep 4]. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/proquad-epar-product-information_en.pdf.

- Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco. Priorix Tetra. Summary of product characteristics [Italian]. [ accessed 2019 Sep 4]. https://farmaci.agenziafarmaco.gov.it/aifa/servlet/PdfDownloadServlet?pdfFileName=footer_000200_038200_RCP.pdf&retry=0&sys=m0b1l3.

- Scott LJ. Measles–mumps–rubella–varicella combination vaccine (ProQuad®): a guide to its use in children in the EU. Pediatr Drugs. 2015;17(2):167–74. doi:10.1007/s40272-015-0123-7.

- Ma S-J, Li X, Xiong Y-Q, Yao A, Chen Q. Combination measles-mumps-rubella-varicella vaccine in healthy children. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(44):e1721. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000001721.

- Shinefield H, Black S, Digilio L, Reisinger K, Blatter M, Gress JO, Brown ML, Eves KA, Klopfer SO, Schödel F, et al. Evaluation of a quadrivalent measles, mumps, rubella and varicella vaccine in healthy children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24(8):665–69. doi:10.1097/01.inf.0000172902.25009.a1.

- Nolan T, McIntyre P, Roberton D, Descamps D. Reactogenicity and immunogenicity of a live attenuated tetravalent measles-mumps-rubella-varicella (MMRV) vaccine. Vaccine. 2002;21(3–4):281–89. doi:10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00459-0.

- Kuter BJ, Hoffman Brown ML, Hartzel J, Williams WR, EvesiKaren A, Black S, Shinefield H, Reisinger KS, Marchant CD, Sullivan BJ, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a combination measles, mumps, rubella and varicella vaccine (ProQuad®). Hum Vaccin. 2006;2(5):205–14. doi:10.4161/hv.2.5.3246.

- Knuf M, Habermehl P, Zepp F, Mannhardt W, Kuttnig M, Muttonen P, Prieler A, Maurer H, Bisanz H, Tornieporth N, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of two doses of tetravalent measles-mumps-rubella-varicella vaccine in healthy children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25(1):12–18. doi:10.1097/01.inf.0000195626.35239.58.

- Czajka H, Schuster V, Zepp F, Esposito S, Douha M, Willems P. A combined measles, mumps, rubella and varicella vaccine (Priorix-TetraTM): immunogenicity and safety profile. Vaccine. 2009;27(47):6504–11. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.07.076.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Epidemiology and prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases. Meningococcal disease. [ accessed 2019 Sep 4]. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/chapters.html.

- Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco. Meningitec. Summary of product characteristics. [ accessed 2019 Sep 5]. https://farmaci.agenziafarmaco.gov.it/aifa/servlet/PdfDownloadServlet?pdfFileName=footer_003835_035438_FI.pdf&retry=0&sys=m0b1l3.

- Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco. Mencevax ACWY. Summary of product characteristics [Italian]. [ accessed 2019 Sep 4]. https://farmaci.agenziafarmaco.gov.it/aifa/servlet/PdfDownloadServlet?pdfFileName=footer_000200_038504_RCP.pdf&retry=0&sys=m0b1l3.

- Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco. Menjugate. Summary of product characteristics [Italian]. [ accessed 2019 Sep 4]. https://farmaci.agenziafarmaco.gov.it/aifa/servlet/PdfDownloadServlet?pdfFileName=footer_007127_035436_RCP.pdf&retry=0&sys=m0b1l3.

- European Agency of Medicines. Menveo. Summary of product characteristics. [ accessed 2019 Sep 5]. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/menveo-epar-product-information_it.pdf.

- Agenzia Italiana per il Farmaco. NeisVac. Summary of product characteristics. [ accessed 2019 Sep 5]. https://farmaci.agenziafarmaco.gov.it/aifa/servlet/PdfDownloadServlet?pdfFileName=footer_004025_035602_FI.pdf&retry=0&sys=m0b1l3.

- European Agency of Medicines. Nimenrix. Summary of product characteristics. [ accessed 2019 Sep 4]. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/nimenrix-epar-product-information_it.pdf.

- Richmond P, Borrow R, Miller E, Clark S, Sadler F, Fox A, Begg N, Morris R, Cartwright K. Meningococcal serogroup C conjugate vaccine is immunogenic in infancy and primes for memory. J Infect Dis. 1999;179(6):1569–72. doi:10.1086/314753.

- MacLennan JM, Shackley F, Heath PT, Deeks JJ, Flamank C, Herbert M, Griffiths H, Hatzmann E, Goilav C, Moxon ER. Safety, immunogenicity, and induction of immunologic memory by a serogroup C meningococcal conjugate vaccine in infants. JAMA. 2000;283(21):2795. doi:10.1001/jama.283.21.2795.

- Levi M, Donzellini M, Varone O, Sala A, Bechini A, Boccalini S, Bonanni P. Surveillance of adverse events following immunization with meningococcal group C conjugate vaccine: tuscany, 2005-2012. J Prev Med Hyg. 2014;55(4):145–51. Accessed 2019 September 4. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26137788.

- Lakshman R, Jones I, Walker D, McMurtrie K, Shaw L, Race G, Choo S, Danzing L, Oster P, Finn A. Safety of a new conjugate meningococcal C vaccine in infants. Arch Dis Child. 2001;85(5):391–97. doi:10.1136/adc.85.5.391.

- Halperin SA, Diaz-Mitoma F, Dull P, Anemona A, Ceddia F. Safety and immunogenicity of an investigational quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine after one or two doses given to infants and toddlers. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010;29(3):259–67. doi:10.1007/s10096-009-0848-8.

- Kurosky SK, Davis KL, Krishnarajah G. Effect of combination vaccines on completion and compliance of childhood vaccinations in the United States. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017;13(11):2494. doi:10.1080/21645515.2017.1362515.

- Schuster V, Otto W, Maurer L, Tcherepnine P, Pfletschinger U, Kindler K, Soemantri P, Walther U, Macholdt U, Douha M, et al. Immunogenicity and safety assessments after one and two doses of a refrigerator-stable tetravalent measles-mumps-rubella-varicella vaccine in healthy children during the second year of life. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27(8):724–30. doi:10.1097/INF.0b013e318170bb22.

- Ministry of Health. Immunisation Handbook 2017. 2nd ed. [ accessed 2019 Sep 4]. https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/immunisation-handbook-2017.

- Government of Canada. Canadian immunization guide: part 1 - key immunization information. [ accessed 2019 Sep 4]. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/canadian-immunization-guide-part-1-key-immunization-information/page-10-timing-vaccine-administration.html.

- GOV.UK. Contraindications and special considerations: the green book. Chapter 6.; 2017. [accessed. 2019 Sep 4]. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/655225/Greenbook_chapter_6.pdf.

- Gallo G, Mel R, Ros E, Filia A Guide to contraindications to vaccinations. Fifth Edition, 2018 [Guida alle Controindicazioni alle Vaccinazioni. Quinta Edizione, 2018]. [Italian]. [ accessed 2019 Sep 4]. http://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_2759_allegato.pdf.

- Italian Society of Hygiene, Preventive Medicine and Public Health - SItI, Italian Federation of Family Pediatricians-FIMP, Italian Federation of General Medicine-FIMMG, Italian Society for Pediatricians-SIP. Vaccination Calendar 2019 [Calendario Vaccinale per La Vita 2019] [Italian]. 2019. [accessed 2019 Sep 4]. http://www.igienistionline.it/docs/2019/21cvplv.pdf.