ABSTRACT

In China, there are about 131,500 new cases of human papillomavirus (HPV) infection every year. However, studies focused on the related cognitions in the general college-going population, who belong to an at-risk age group and are of childbearing age, are relatively limited. Thus, this cross-sectional online survey study, conducted from December 2018 to March 2019, sought to investigate HPV vaccination rates, knowledge, acceptance, and associated factors in this population. Descriptive analysis and ordinal logistic regression analysis were conducted to analyze the factors associated with HPV vaccination intention. A total of 1,029 questionnaires were collected, of which 1,022 were valid (males: 267, females: 755). As per the results, only 3.1% of the sample had been vaccinated against HPV. The overall levels of knowledge about HPV and its vaccination were low. Male students’ knowledge about HPV types, infection symptoms, vaccination cycles, and preventable diseases was significantly lower than that of female students. As for acceptance, only 36.9% of females and 24.8% of males indicated that they would choose to undergo HPV vaccination. Chinese college students’ knowledge of HPV and its vaccination is limited. More than half of the sample was unsure about undergoing HPV vaccination, with concerns about safety and effectiveness serving as the main barriers. Measures such as strengthening health education, improving vaccination safety and effectiveness, and reducing vaccine prices should be taken to promote HPV vaccination among Chinese college students.

Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common viral infection of epithelial tissues, transmitted sexually through skin contact.Citation1 In addition to genital warts, HPV infection can cause a variety of cancers specific to women (cervical, vaginal, vulvar) and men (penile), as well as those common to both sexes (oropharyngeal, anal).Citation1 HPV infection has become a worldwide public health problem.Citation2 According to a 2017 report, the global rate of HPV infection in women was 11.7% while that in Asian women was 14.0%.Citation3 Moreover, HPV infection rates range from 2.0% to 93.0% in high-risk men (sexually transmitted infection in patients with human immunodeficiency virus with a female sexual partner infected with HPV) and from 1.0% to 84.0% in low-risk men.Citation3 The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) predicts that sexually active individuals who have not been vaccinated for HPV will be a factor in up to 80.0% of HPV infections.Citation4

In China, there are 131,500 new HPV infections every year.Citation5 According to the Global Burden of Disease 2018 cancer report, cervical cancer ranked 10th among the tumors with the highest annual years of life lost due to early death in 2016 and is the second most serious cancer threat for people aged 20 to 39.Citation6 Among the various types of cancer, approximately 91.0%, 75.0%, 63.0%, and 91.0% of the cases of cervical, vaginal, penile, and anal cancer, respectively, are associated with HPV infection.Citation7 Meanwhile, the perception that it is mainly women who are afflicted with HPV-related cancers has changed; it is now evident that men are more likely to be afflicted with head and neck cancers and anal cancers. Head and neck cancers rank second in HPV-related cancers (38,000 new cases annually), while anal cancer ranks third (35,000 new cases annually).Citation3 In China, the death rate of cervical cancer ranks 10th among all cancers.

There are three types of HPV vaccines. As of March 31, 2017, 71 countries (37.0%) had included an HPV vaccine in their national immunization programs for females, and 11 countries (6.0%) had also included it in their federal immunization programs for males. The GSK 2vHPV vaccine was introduced to the Chinese mainland in August 2016, with the 4vHPV vaccine and 9vHPV vaccine launched in 2017 and 2018, respectively. Owing to the lack of opacity of relevant Chinese data, it is impossible to provide accurate statistics. However, according to the latest meta-analysis of more than 60 million people in 14 countries over eight years, countries with multi-age vaccination and high vaccination coverage have greater direct and group effects of vaccine protection.Citation8

Based on US data from 2009 to 2012, the highest prevalence of HPV infection is among women aged 20–24 (57.9%).Citation9 However, empirical research on the approval of the HPV vaccines in China is very limited. Most Chinese research on HPV and HPV vaccination awareness has only targeted women because the government has not recommended that men also undergo vaccination. College students not only fall in the age group at high risk for HPV infection but are also of childbearing age; thus, their attitudes not only affect current vaccination rates but also those of the next generation. Therefore, understanding the cognitions and attitudes toward HPV of this target population is of great significance for the promotion of HPV vaccination and the prevention of HPV-related cancers.

The main purpose of this study is to explore the current situation regarding knowledge of HPV and its vaccine in Chinese college students and the factors related to vaccination intention. Further, we hope to provide basic information for the development of health service programs to improve the HPV vaccination rate in this population.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

For this cross-sectional study, 1,029 Chinese college students living in mainland China were recruited through convenience sampling between December 2018 and March 2019. A link to the online questionnaire survey, administered in Chinese, was generated through the survey platform WJX.cn. Then, the questionnaire was published and the response URL and 2D barcodes were created. The response URL and 2D barcordes were sent by our collaborating college faculty to invite their students to participant in the study. The respondents answered the questionnaire by logging in to the website through a browser or scanning the QR code on their mobile phone. The website was sent by our collaborating universities’ or colleges’ faculties to their students. To gain a comprehensive understanding of the overall situation of HPV-related knowledge, vaccination willingness, and associated factors in the target population, the survey was conducted on college students across China regardless of region or major.

Considering HPV infection can affect both men and women and in many countries, men are also HPV vaccination targets,Citation1 the participants of this study included both males and females. The inclusion criteria were: (1) college students, (2) Chinese nationals, and (3) ability to read Chinese. The respondents were informed of the purpose and contents of the survey and provided informed consent before filling it out. To prevent response bias, participants were assured of anonymity and the fact that their personal information would be strictly confidential. Teachers from various schools sent the questionnaire link to the students to ensure that the targets met the research requirements. Respondents did not receive any compensation for their cooperation.

Instruments

Based on the foundation of the health belief model and analysis of the relevant literature, we developed a 72-item self-reported online knowledge-attitude-behavior questionnaire that covered four main aspects: (1) awareness and knowledge of HPV and its vaccination, (2) HPV risk perception, (3) vaccination intention, and (4) analysis of related factors of HPV vaccination. The questionnaire was finalized after numerous expert consultations to determine its reliability and validity. Internal consistency, as determined by Cronbach’s alpha, was 0.983 and the Spearman-Brown split-half reliability coefficient was 0.826. Further, the content validity index, evaluated by an expert group of five obstetricians and gynecologists with more than 10 years of experience, was 0.87.

Statistical analysis

The completed questionnaires were imported into Microsoft Excel 2016, and statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 24.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Based on the sample’s sociodemographic characteristics, HPV and HPV vaccination knowledge, attitudes toward vaccination and related factors, and the reasons for vaccination willingness were stratified by gender. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and categorical variables as frequency and percentage. The chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test were used to compare intergroup differences. Self-reported HPV vaccination willingness, which served as the dependent variable, was categorized as “yes,” “uncertain,” and “no,” using ordinal logistic regression analysis to identify the associations of the factors concerning male and female students’ willingness to vaccinate against HPV.

Results

General demographic analysis and HPV vaccination rate

After excluding seven questionnaires owing to incomplete responses, the data of 1,022 participants were analyzed. The mean age of the sample, which included 267 (26.1%) males and 755 (73.9%) females, was 20.35 ± 3.49 years. Among the participants, 570 (55.8%) were urban residents, 366 (35.8%) were rural residents, and 86 (8.4%) lived in the suburbs. Regarding sexual orientation, 609 (88.6%) identified as heterosexual, and sexual history was available for 161 (15.8%) participants. Of the final sample, only 3.1% had been vaccinated against HPV, including five males and 27 females. Other demographic results are presented in .

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of study participants(n = 1022)

Knowledge of HPV and its vaccination

is a representation of the sample’s knowledge of HPV and its vaccination. Regarding knowledge of HPV infection, the number of females who correctly responded to the questions about whether HPV requires regular screening and the connection between the occurrence of cervical cancer and HPV infection was significantly higher than that of males, with statistically significant differences (p < .05). Females were also more likely than males to know that HPV is divided into high-risk and low-risk types (29.1% vs. 18.0%), with statistically significant differences (p < .05). However, there was no significant difference in the response to the question about which types of HPV are the riskiest (4.2% vs. 2.3%).

Table 2. Chinese college students’ knowledge of HPV and HPV vaccination

Vaccination-related knowledge was at a higher level than HPV -related knowledge. The majority of the participants correctly answered the questions about whether women need routine gynecological examination after HPV vaccination (68.0% vs. 32.0%) and whether HPV vaccination is required if one is not engaging in sexual intercourse (61.4% vs. 38.7%). More females than males had knowledge of the HPV vaccination cycle (9.5% vs. 2.6%) and the most appropriate time for HPV vaccination (28.6% vs. 18.4%), with statistically significant differences (p < .05).

The results showed that fewer males than females answered correctly about HPV and its vaccination. However, males were more likely than females to identify HPV risk factors (2.6% vs. 1.5%) and types of HPV vaccine (16.1% vs. 12.1%), although the differences were not statistically significant. The question on HPV’s transmission route received no correct answers; every participant answered this wrong.

HPV vaccination intention

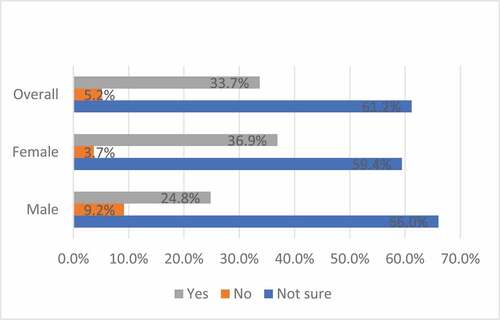

depicts the acceptance of the HPV vaccine. As for participants’ intention to undergo HPV vaccination, 61.2% indicated that they were unsure, while 36.9% of females and 24.8% of males, respectively, said that they would undergo it.

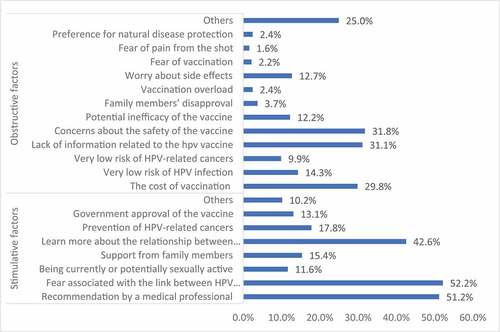

depicts facilitators of and barriers to HPV vaccination acceptance. The top three promoting factors were fear associated with the link between HPV infection and cancer (52.2%), recommendation by a medical professional (51.2%), and learn more about the relationship between human papillomavirus and cancer (42.6%). The top three obstacles were concerns about the safety of the vaccine (31.8%), lack of information related to the hpv vaccine (31.1%), and the cost of vaccination (29.8%).

Factors associated with vaccination acceptance

A multivariate logistic regression analysis of the factors associated with HPV vaccination acceptance was conducted (). Further, the dependent variables of male and female acceptance were individually analyzed. The results showed that the factors associated with higher HPV vaccination rate in the entire sample were: vaccination being an effective safeguard against disease (odds ratio (OR) = 1.479, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.151–1.899, p = .002), the necessity of receiving all vaccinations (OR = 1.435, 95% CI 1.190–1.730, p = .000), and ensuring others’ safety by undergoing vaccination (OR = 1.226, 95% CI 1.021–1.473, p = .029). Regarding the factors associated with higher vaccination acceptance, although not all options were statistically significant, the OR values were all ˃ 1 and close to each other. The risk factors for these variables were similar after deducting the effects of other independent variables.

Table 3. Multivariable logistic regression analysis for factors associated with acceptability of HPV vaccine

Among the barriers, the high cost of the vaccine (OR = 1.209, 95% CI 1.008–1.451, p = .041) was the most important. Unlike males, females did not generally consider the risk of HPV-induced cancer to be high, and therefore did not find it necessary to undergo vaccination (OR = 0.526, 95% CI 0.298–0.930, p = .027). For males, the feeling of already having received too many vaccines (OR = 2.651, 95% CI 1.080–6.509, p = .033) was also one of the main factors that prevented them from undergoing HPV vaccination.

Discussion

Demographic characteristics of college students in mainland China

Since the development of HPV vaccines, numerous research articles on related cognitive, attitudinal, and behavioral tendencies in college students have appeared in China.10−1Citation6 Most of these have been conducted in the same region or institutionCitation10 or only among femaleCitation11 and medical students. Further, some were conducted when the vaccine was not listed in China.Citation12–16 Therefore, this study investigated the awareness and attitude of college students with regard to HPV and its vaccine irrespective of region, major, or gender. According to the survey results, only 3.1% of the participants had been vaccinated against HPV, which is much lower than the 17.0–81.0% coverage rates reported in Western countries.

Compared to previous studies on Chinese college students, the participants in this study had a better understanding of HPV and its vaccination. According to the questionnaire survey, 43.8% had heard of HPV and 41.2% had heard of a vaccine for it. By comparison, in a 2014 survey, only 14.3% and 8.1% of undergraduates had heard of HPV and its vaccine, respectively.Citation16 In a 2016 investigation of awareness of HPV and its vaccine among students of Ningbo University, the figures stood at 11.2% and 6.1%, respectively.Citation17 In a study of college students in Changsha city conducted in 2017, awareness of HPV vaccination was 32.4%.Citation18 In 2019, as per the results of a cognitive survey of college students in Chongqing, awareness of HPV was 21.4%, while awareness of the vaccine was 13.3%.Citation19 Finally, in a 2017 cognitive survey of college students in Xiamen, students’ HPV vaccine-related knowledge rate was 24.2%.Citation20 In comparison, the higher rates in the present study are attributable to the fact that since a fair amount of time has now elapsed since the introduction of the vaccine, awareness over the years has improved.

Knowledge of HPV and its vaccine

It has been demonstrated that despite some improvements over the years, Chinese college students still have limited knowledge about the symptoms of HPV infectionCitation16 and a low level of understanding of HPV and its vaccination. In this study, the results were similar. Only 29.6% of the participants were aware that the occurrence of cervical cancer is closely related to HPV infection, and only approximately 27.0% could correctly answer the question about the lesions caused by low-risk HPV. This may be owing to the relatively recent introduction of the vaccine in China, the lack of publicity, and the cultural reservations about publicly discussing sex.

The participants also had a poor understanding of the transmission of HPV. While a relatively high proportion understood that HPV is transmitted sexually, only 1.8% could correctly answer the question about high risk factors for HPV infection. However, 60.0% of the participants believed that having multiple sexual partners is a high risk factor for HPV infection, and 37.9% considered early sexual initiation (< 16 years) a high risk factor for HPV infection. When asked about HPV vaccination, the female participants showed a higher level of knowledge than males, which is similar to the results of other domestic and foreign studies.

Although men are advised to undergo HPV vaccination, there are currently no approved recommendations or HPV testing methods for them,Citation21 and the US healthcare system does not encourage males to undergo routine screening. Only those who are at high risk of anal cancer, including males with other HPV types of cancer and those engaging in anal sex, receive HPV testing on the recommendation of a doctor.Citation21 Similarly, in Chinese mainland, the government did not list men as the HPV vaccine inoculation population. Further, because the term “cervical cancer vaccine” is often used in the marketing of the HPV vaccine, one might assume that it is not relevant to men. However, oropharyngeal cancer is the most common HPV-related cancer in men. Nearly four out of every 10 cancers caused by HPV occur in men. Every year in the US, more than 13,000 men develop cancer due to HPV.Citation7 According to research, the most effective way for male college students to increase their understanding of HPV is through educational programs in schools and the internet.Citation22

Attitudes toward HPV and vaccination

The results showed that only 18.7% of the participants considered themselves at risk of HPV infection. As per the literature, lack of sexual experience, maybe they think they are one of the reasons there is a lower risk of HPV infection; according to a report from Hong Kong, only 8.0% of Chinese adolescent girls are sexually active (median age 16 years, age range 13–20, n = 64).Citation23 In this study, of the 15.8% who had sexual experience, 12.7% were females; among females, 21.2% considered themselves at risk of contracting HPV. This result is similar to the finding reported by a UK Systematic Review, wherein 21.0–46.0% of teenagers and young females thought they were at risk for HPV.Citation24 It is generally believed that the HPV vaccine has nothing to do with men, and this was also true in this study, where only 12.0% of males thought they were at risk for HPV infection and 21.4% thought men could not be infected with HPV.Citation25–28 The overwhelming majority of participants believed the HPV vaccine is safe and effective in preventing the genital warts and cervical cancer caused by HPV infection. These results are similar to those of a previous study.Citation29 As for the overall sample’s willingness to undergo HPV vaccination, 61.2% expressed uncertainty, while 36.9% of females and 24.8% of males stated that they would undergo vaccination. Greater knowledge of the HPV vaccine and stronger social support will improve vaccination intention.Citation30

In previous studies, Chinese college students demonstrated higher acceptance of HPV vaccination. Over the years, these rates have been 57.2% in Beijing college students (2012);Citation12 71.9% in Shanghai college students (2014);Citation13 75.4% in Guangzhou college students (2015);Citation14 and 79.9% in Xi’an female college students (2015).Citation15 This difference may be attributable to the fact that this study was not exclusively targeted at medical or female students. Further, there were several adverse vaccination-related events in China in 2018, leading to a decrease in trust in vaccination, in turn, resulting in lowered vaccination intention in this study.

Factors related to vaccination acceptance

In this study, the HPV vaccination rate was 3.1% (females: 3.6%, males: 1.9%). In comparison, in an American study of women between the ages of 18 and 26, 26.8% of the participants had initiated the HPV vaccination schedule and 15.6% had completed it.Citation31 The relatively late introduction of the HPV vaccine in mainland China may be the main reason for the difference.

Our findings, consistent with those of other studies, suggest that the primary factor associated with HPV vaccination in college students is safety and efficacy.Citation16 Effective disease prevention is one of the main factors in promoting HPV vaccination acceptance. Further, consistent with the literature, participants reported that a primary factor associated with vaccination acceptance was recommendations from doctors and nurses.Citation21,Citation32,Citation33 Schools, in conjunction with medical and health institutions, must conduct regular on-campus lectures to promote knowledge of HPV and its vaccine as well as vaccination acceptance. Some studies have also suggested that parental opinion is the main factor influencing whether college students undergo HPV vaccination.Citation34 Studies in Hong Kong have shown that in addition to parental support, young women are motivated by the fear of future HPV infection.Citation23,Citation35 However, the effectiveness of vaccination in reducing cancers caused by HPV infection was not a factor in their decision to get vaccinated. Only 12.1% of college students thought they might develop cancer if they were infected with HPV.

The main reasons for not undergoing HPV vaccination revolved around concerns about the difference between the ideal and actual price, a matter that requires governmental policy intervention and support. In mainland China, medical insurance does not include HPV vaccines, and individuals must bear the cost. The price of three shots is between 2,000 and 4,000 yuan, or about 500 US dollars. This is not a small sum for college students. In this study, 56.0% of the participants said that the high cost was one of the main deterrents. This is consistent with previous research.Citation23,Citation35–37 Therefore, the cost of vaccination is one of the main factors preventing college students from undergoing vaccination. However, researchers who have studied mothers’ attitudes toward HPV vaccination point out that because vaccines can prevent potentially life-threatening diseases, they tend to consider the cost of vaccination to be “reasonable”.Citation38 Although the previously mentioned study was concerned with mothers, it can be speculated that differences in the perceptions of vaccination costs may be associated with socioeconomic status, which may be one of the factors in deciding whether or not to undergo HPV vaccination. At the same time, the lack of information about HPV vaccination and concerns about side effects and potential safety problems also hinder HPV vaccination. This finding is consistent with other studies.Citation28 Health education for vaccines and the development of healthy behaviors not only depends on publicity and support from the government, medical institutions, and schools but also the improvement of HPV awareness in the entire population. Only by recognizing the severity and consequences of HPV and the effectiveness of the vaccine can the vaccination rate be improved.

Gender differences in risk of infection and cost-effectiveness

For women, simple and quick screening for precancerous lesions can help detect cervical cancer, but there is no such option for anal and oropharyngeal cancer screening in men. The incidence rate of oral and nasal cancers caused by HPV is increasing in the US, and the impact on men is greater than on women. There are studies dedicated to the cost-effectiveness of HPV vaccination in men. Some scholars think that the cost-effectiveness of promoting male vaccination is low when the female vaccination rate is high. However, in countries where male vaccination has been recommended, cost-benefit models have shown that male vaccination can be more cost-effective.Citation39 In China, HPV vaccination was introduced relatively recently. If the vaccine can cover the whole population, it will greatly reduce the burden of HPV-related diseases in the country. Further, the idea that both men and women should get vaccinated rather than women alone undergoing HPV vaccination has also been recognized by a recent meta-analysis.Citation8 Educating and encouraging male college students to get vaccinated not only reduces the chance that men will be infected with HPV but can also help guide and educate other groups (such as relatives, female friends, and children) so as to achieve long-term improvement of the HPV vaccination rate and reduce the effect of HPV-related diseases.

Limitations

This study has several notable limitations. First is the cross-sectional design, which limits the possibility of making inferences about causal relationships between variables. Second, the generalizability of the findings is limited. This is because, owing to the limitation inherent in convenience sampling, most of the respondents were from universities in Hubei, Hebei, Shanxi, and Beijing. At the same time, the HPV vaccination cycle is relatively long, and owing to limited supply, the vaccination appointment system is not perfect. Most vaccination institutions use a three-time payment to ensure that the vaccinated population can effectively complete the three doses. In this study, people who received one, two, or three doses were classified as having been vaccinated. However, the Chinese government has no public data to indicate whether there are differences in HPV vaccination rates among different provinces in China. Therefore, this study cannot explore the reasons for the differences in HPV vaccination rates among different regions. Further, only a small number of participants from the 1,022 whose data were analyzed had characteristics that could be associated with their HPV vaccination intention; for example, people who know someone who has HPV or has cancer caused by it or have heard of someone who has cancer caused by HPV. Third, the self-reported questionnaire format involves recall bias, and the possibility of social expectation bias cannot be eliminated either. Finally, our study investigated a variety of factors related to vaccination acceptance but did not explore other potential variables that might be related to vaccination in this population. Despite the above limitations, our study could provide data that could help publicize HPV vaccination and promote health education.

Implications and suggestions

In general, females are relatively well informed about HPV infection, transmission, and vaccination. In order to improve the HPV vaccination rate and prevent cervical cancer, schools should provide relevant health education.Citation40 While the CDC recommends that men be vaccinated, China does not include men in the HPV vaccination schedule. We found that among male college students in China, awareness and coverage rates of HPV vaccination are relatively low. Our results indicate that it is necessary to publicize the necessity of male HPV vaccination to improve the vaccination rate. Further, there is a need to develop HPV-related educational materials targeted at males to promote their understanding and to further study male views on HPV vaccination and its long-term impact.

The results show that the most crucial factor in promoting HPV vaccination is safety and efficacy, while the main barrier is the cost of vaccination. It has also been reported that most parents prefer vaccinations that are recommended and organized by schools rather than going to other places for vaccinations.Citation36 Recommendations from doctors and nurses are also crucial in promoting HPV vaccination. The government could also consider offering some subsidies to university students who undergo HPV vaccination. Vaccination through schools and government subsidies can reduce the cost of HPV vaccination for college students, reduce the psychological barriers of vaccination, and improve the vaccination rate. Therefore, future studies can focus on examining the feasibility of providing HPV vaccination in schools and the long-term effects of HPV vaccination in preventing HPV infection and related cancers.

Conclusion

In Chinese college students, the understanding of the causal relationship between HPV and cervical cancer was better than their awareness of the various aspects of HPV. Overall knowledge levels in females were higher than those in males. The low risk perception of HPV infection, and subsequently cancer, is a major obstacle to HPV vaccination. Strengthening health education on HPV and its vaccination, reducing vaccine prices, and ensuring the safety and effectiveness of vaccines will help promote HPV vaccination among college students.

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

Che Deng was involved in the conception and study design, data acquisition and analysis, interpretation of the data, and manuscript writing. Yanqun Liu,Xiaoli Chen was involved in the conception and study design and manuscript writing. The author, Che Deng, wrote the first draft. All authors have approved the final version of the article. We thank Junying Zhao for their unfailing support with the data acquisition.

Additional information

Funding

References

- ACS. HPV and cancer. American Chemical Society, 2017.

- Ferlay J, Shin H-R, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2893–917. doi:10.1002/ijc.25516.

- WHO. Human papillomavirus vaccines: WHO position paper, May 2017. May 2017.

- CDC. 2019. Reasons to Get Vaccinated. United States: Center for Disease Control and Prevention; [accessed 2019 March 26, 2019]. https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/parents/vaccine/six-reasons.html

- Liu P. Big data evaluation of the clinical epidemiology of cervicalcancer in mainland China. Chin J Prac Gynecol Obstetr. 2018;34:41–45.

- Jemal A, Simard EP, Dorell C, Noone A-M, Markowitz LE, Kohler B, Eheman C, Saraiya M, Bandi P, Saslow D, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2009, featuring the burden and trends in human papillomavirus (HPV)–associated cancers and HPV vaccination coverage levels. JNCI: J Nat Cancer Inst. 2013;105(3):175–201. doi:10.1093/jnci/djs491.

- CDC. HPV Diseases and Cancers. 2019.

- Drolet M, Bénard É, Pérez N, Brisson M, Ali H, Boily M-C, Baldo V, Brassard P, Brotherton JML, Callander D, et al. Population-level impact and herd effects following the introduction of human papillomavirus vaccination programmes: updated systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet. 2019;394:497-509.

- Markowitz LE, Liu G, Hariri S, Steinau M, Dunne EF, Unger ER. Prevalence of HPV after introduction of the vaccination program in the United States. Pediatrics. 2016;137(3):e20151968. doi:10.1542/peds.2015-1968.

- Liu Y, Di N, Tao X. Knowledge, practice and attitude towards HPV vaccination among college students in Beijing, China. Human Vaccines Immunother. 2020;16:116–23

- You H, Li H, Wong. Human Papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine uptake and the willingness to receive the HPV vaccination among female college students in China: a multicenter study. Vaccines. 2020;8:31.

- Li M, Ju LR, Li BL, Liu F, Zhou JY, Qi Q. Survey of the cognition on human papillomavirus and it’s preventive vaccine of junior schoolstudents’ parents and university students in Beijing. Chin J Woman Child Health Res. 2013;1:14–17.

- Lu J, Mu W, Jiang MB, Zhang GH, Wang J, Yan L, He JX. A survey on the knowledge of HPV and HPV vaccine among some college students in Shanghai. Shanghai Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2015;27:762-6.

- Pang ZM, Chen XJ, Xiang YW. Cognition and inoculation willingness factors of human papilloma virus vaccines among female college students in Guangzhou University Town. Health Med Res Prac. 2016;13:22–4+31.

- Yang J, Xu LJ, Xu L, Yu M, Chen YM, Nie N. Awareness of HPV and HPV vaccine among non-medical specialty female college students in Xi’an City. Chin J Woman Child Health Res. 2016;27:923–25.

- Wang SM, Zhang SK, Pan XF, Ren ZF, Yang CX, Wang ZZ, Gao XH, Li M, Zheng QQ, Ma W, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccine awareness, acceptability, and decision-making factors among Chinese college students. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2014; 15:3239-45

- Liu RJ, Lu QR, Xia YY, Zhang J, Huang Q. A survey of college students’ cognition and attitude towards human papillomavirus vaccine in Ningbo. Modern Prac Med. 2017;29:92–94.

- Zhu YR, Hu XL, Sheng CH. Survey on college students' cognition and attitude towards HPV vaccine. Today Nurse 2017;3:25–7

- Ma W, Xie XQ. Cognitive analysis of human papillomavirus and its vaccine in Chongqing university students. Electr J Clin Med Liter. 2019;6:181.

- Song QQ, Zhang YJ, Yang CQ, Fang JY, Chang JF, Li SP, Wei FX, Su YY, Wu T. Awareness of human papillomavirus vaccine and willingness to vaccination among college students in Xiamen. Chinese Journal of Health Education 2019;35:705–10

- Rothman SM, Rothman DJ. Marketing HPV vaccine: implications for adolescent health and medical professionalism. JAMA. 2009;302(7):781–86. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1179.

- Breny JM, Lombardi DC. ‘I don’t want to be that guy walking in the feminine product aisle’: a Photovoice exploration of college men’s perceptions of safer sex responsibility. Global Health Promotion 2017;26:6–14.

- Kwan T,Chan K, Yip AMW, Tam KF, Cheung ANY, Young PMC, Lee PWH, Ngan H. Barriers and facilitators to human papillomavirus vaccination among Chinese adolescent girls in Hong Kong: A qualitative-quantitative study. Sexually transmitted infections 2008;84:227-32.

- Brewer NT, Fazekas KI. Predictors of HPV vaccine acceptability: A theory-informed, systematic review. Prev Med. 2007;45:107–14. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.05.013.

- Javaid M, Ashrawi D, Landgren R, Stevens L, Bello R, Foxhall L, Mims M, Ramondetta L. Human papillomavirus vaccine uptake in texas pediatric care settings: a statewide survey of healthcare professionals. J Community Health. 2017;42(1):58–65. doi:10.1007/s10900-016-0228-0.

- Holman DM, Benard V, Roland KB, Watson M, Liddon N, Stokley S. Barriers to human papillomavirus vaccination among us adolescents: a systematic review of the literature. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(1):76–82. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2752.

- Fisher WA, Kohut T, Salisbury CMA, Salvadori MI. Understanding human papillomavirus vaccination intentions: comparative utility of the theory of reasoned action and the theory of planned behavior in vaccine target age women and men. J Sexual Med. 2013;10(10):n/a-n/a. doi:10.1111/jsm.12211.

- Choi EPH, Wong JYH, Lau AYY, Fong DYT. Gender and sexual orientation differences in human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine uptake among chinese young adults. Int J Env Res Public Health. 2018;15(6):1099. doi:10.3390/ijerph15061099.

- Dinh TA, Rosenthal SL, Doan ED, Trang T, Pham VH, Tran BD, Tran VD, Bao Phan GA, Chu HKH, Breitkopf CR. Attitudes of mothers in Da Nang, Vietnam toward a human papillomavirus vaccine. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40(6):559–63. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.02.003.

- Adjei Boakye E, Lew D, Muthukrishnan M, Tobo BB, Rohde RL, Varvares MA, Osazuwa-Peters N. Correlates of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination initiation and completion among 18-26 year olds in the United States. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2018;14:2016–24

- Rosenthal SL, Weiss TW, Zimet GD, Ma L, Good MB, Vichnin MD. Predictors of HPV vaccine uptake among women aged 19–26: importance of a physician’s recommendation. Vaccine. 2011;29:890–95. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.12.063.

- Thompson EL, Vamos CA, Straub DM, Sappenfield WM, Daley EM. Human papillomavirus vaccine information, motivation, and behavioral skills among young adult US women. J Health Psychol. 2018;23(14):1832–41. doi:10.1177/1359105316672924.

- Wilson AR, Hashibe M, Bodson J, Gren LH, Taylor BA, Greenwood J, Jackson BR, She R, Egger MJ, Kepka D, et al. Factors related to HPV vaccine uptake and 3-dose completion among women in a low vaccination region of the USA: an observational study. BMC Womens Health. 2016;16(1):41. doi:10.1186/s12905-016-0323-5.

- Rosen BL, Bishop JM, McDonald S, Wilson KL, Smith ML. Factors associated with college women’s personal and parental decisions to be vaccinated against HPV. J Community Health. 2018;43(6):1228–34. doi:10.1007/s10900-018-0543-8.

- Loke AY, Chan ACO, Wong YT. Facilitators and barriers to the acceptance of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination among adolescent girls: a comparison between mothers and their adolescent daughters in Hong Kong. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10(1):390. doi:10.1186/s13104-017-2734-2.

- Brabin L, Roberts SA, Farzaneh F, Kitchener HC. Future acceptance of adolescent human papillomavirus vaccination: A survey of parental attitudes. Vaccine. 2006;24(16):3087–94. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.01.048.

- Lu J, Mu W, Zhou WY, Jing MB. Survey of awareness and attitudes of human papilloma virus vaccine among college students, government officials and medical Staff in Shanghai. Chin J Vacc Immun. 2016;22:70–75.

- Kwan T, Chan K, Yip A, Tam K, Cheung A, Lo S, Lee P, Ngan H. Acceptability of human papillomavirus vaccination among Chinese women: concerns and implications. BJOG: An Int J Obstetr Gynaecol. 2009;116(4):501–10. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01988.x.

- Stanley M. HPV vaccination in boys and men. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics. 2014;10(7):2109–11. doi:10.4161/hv.29137.

- Lee PWH, Kwan TTC, Tam KF, Chan KKL, Young PMC, Lo SST, Cheung ANY, Ngan HYS. Beliefs about cervical cancer and human papillomavirus (HPV) and acceptability of HPV vaccination among Chinese women in Hong Kong. Prev Med. 2007;45(2–3):130–34. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.07.013.