ABSTRACT

Varicella live attenuated vaccine led to a significant reduction in morbidity and mortality from varicella zoster disease. Vaccine adverse effects are mostly mild. Immunosuppression is the main risk factor for severe varicella. Risk factors for disease following vaccination are less studied. We report a 12-month-old infant with no T-cell immunodeficiency who developed severe varicella infection by vaccine strain.

Introduction

Chicken pox is a highly contagious disease caused by varicella zoster virus VZV. It is generally self-limited and complications are rare in healthy children.Citation1 Varicella live attenuated vaccine was introduced in the US routine vaccination childhood program in 2006.Citation2 Before vaccine introduction, varicella was responsible for thousands of hospitalizations and deaths per year. Two decades following vaccination, a 94% decline was noticed in overall mortality from varicella.Citation3

Breakthrough varicella is a disease caused by wild-type virus in a person who received at least one dose of varicella vaccine ≥42 d before symptoms. It is generally milder in severity and duration than in unvaccinated persons.Citation4

In contrast to breakthrough varicella, there is only scarce data about vaccine strain associated varicella. The 22-y review of the vaccine safety data presented a summary of all cases of varicella afterward.Citation5 Most cases of disseminated disease caused by vaccine strain occurred in immunocompromised patients. Only few of these cases were described in patients treated with steroids. In fact, although it is a well-known risk factor for severe varicella infection in unvaccinated persons,Citation6 yet, in the post vaccination era, there are only few reports on steroid treatment as a risk factor of vaccine strain varicella infection.

In this paper, we present a case of varicella infection caused by vaccine strain VZV in a 12-month-old child, not known to have a T-cell immunodeficiency nor under chronic immunosuppressive therapy.

Patient presentation

We describe a 12-month-old child with congenital cyanotic heart disease and asplenia, and under chronic treatment with furosemide, acetylsalicylic acid, captopril, and preventive antibiotic treatment of amoxicillin with no prior history of recurrent or severe infections except one episode of urinary tract infection at the age of 11 months.

At the age of 12 month, the patient presented to the emergency room with high-grade fever and cyanosis, earlier at the same day she was immunized with the combined measles-mumps-rubella-varicella (MMRV) vaccine. Physical examination upon arrival showed body temperature 40° C, pulse 210, BP 73/59, 67% oxygen saturation, cold periphery, delayed capillary refill, and depressed consciousness. Her clinical status deteriorated rapidly and she developed severe septic shock with multi-organ failure including hemodynamic collapse and respiratory failure ultimately needing intubation and treatment with adrenalin drip after which the patient was admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU). Blood culture was drawn, and she was treated with ceftriaxone, clindamycin, and amikacin. Four hours later, Gram-positive streptococci was detected and later defined as a non-vaccine type Streptococcus pneumoniae (Serotype 24 F). Depending on susceptibility profile ceftriaxone (MIC 0.12) was continued as a single treatment. Moreover, hydrocortisone was started as a treatment for inotropes resistant shock, first at a stress dose of 8 mg/kg/day (equivalent to 2 mg/kg/day Prednisone), then was lowered gradually until a maintenance dose of 1.5 mg/kg/day and was stopped eventually 25 d after admission.

Overall, PICU stay was characterized by gradual deterioration and multi-system involvement including cerebral edema and infracts, renal failure, purpura fulminans with massive limb necrosis, and secondary aspergillus skin infection that was treated with voriconazole.

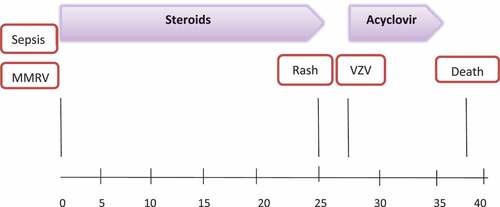

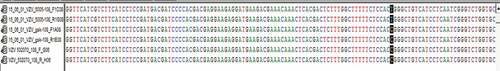

At d 25 of admission, (25 d post MMRV vaccination) she developed a vesicular rash which was first noticed on the forehead and scalp and later spread to full-body vesiculobullous rash. A skin lesion specimen collected was positive for VZV by polymerase chain reaction. DNA sequencing showed a VZV vaccine strain (). The patient was treated with acyclovir for 7 d until complete resolution of all lesions. The sequence of events and therapies throughout the timeline is described in . Patient’s family, medical, and nursing staff at PICU ruled out any signs of VZV clinical disease.

Figure 1. Distinguishing of vaccine type virus isolate from wild type was done by PCR amplification of two vaccine specific SNPs sites (106262 and 108111), followed by sequencing of the amplicons using standard laboratory methods. Shown is partial DNA sequencing of wild type VZV (the 1st 2 rows), vaccine type VZV (middle rows) and the virus type isolated from the patient (the final rows). Note that the patient isolate is similar to the vaccine strain VZV at the 108111 position (black highlight); not shown is the rest of the sequence which is similar between the 3 types

As mentioned, the patient’s condition worsened gradually, exhibiting multi-organ failure. At her last days, because of her poor prognosis, and after parents’ consent, she was provided comfort care and ultimately died after hemodynamic deterioration 38 d post admission.

Discussion

We report a 12-month-old child, who developed varicella infection from a vaccine strain VZV during her hospitalization in PICU. The patient did not have a prior history of T-cell immunodeficiency or was under chronic treatment with immunosuppressive drugs.

In their comprehensive review, Woodward et al.Citation5 presented a summary of all cases of varicella infection after vaccination until the year 2017. Of all cases of varicella infection reported during this period (11,095 cases), a lesion sample was undertaken from 204 patients and documented a vaccine strain VZV in 67 patients. Disseminated disease caused by vaccine strain VZV was confirmed by PCR analysis in 39 cases. Eleven cases occurred in immunocompetent individuals, and 28 involved patients who had underlying immunosuppressive conditions including T-cell related immune deficiency, HIV, and malignancy and/or who reported concomitant use of immunosuppressant therapies. In immunocompetent patients, all the eleven cases of disseminated disease from vaccine strain VZV occurred 5.5 y in average after vaccine administration and no mortality was reported. In this review, there were 11 fatal cases of varicella, two of which were confirmed as vaccine strain. The first case describes a 13-month-old patient with underlying immunodeficiency that acquired disseminated varicella infection from vaccine strain 21 d post vaccination. Patient died due to multi-organ failure associated with disseminated varicella 7 weeks after varicella vaccination.Citation5 The second case describes a 15-month-old female who developed varicella from vaccine strain 20 d after vaccination. Although the patient did not have a diagnosed primary immune deficiency, her failure to thrive and repeated early hospitalizations for presumed infections and respiratory events requiring treatment with corticosteroids were suggestive of a primary immune deficiency.Citation5

Despite the lack of obvious immunocompromised state in some cases of vaccine strain associated varicella, patients were suspected to have an underlying previously undiagnosed immunodeficiency.

In addition to these cases mentioned in the review above, there is only another case report of varicella from vaccine strain which ended with death. It is described in a 4 y old girl with acute lymphoblastic leukemia who acquired varicella infection 32 d post vaccination which was given 5 months after complete remission; at that time lymphocyte count was normal, and chemotherapy was interrupted for 1 week before and after vaccination. The clinical picture included rash, pneumonitis, hepatitis, and CNS symptoms. The patient died of multi-organ failure 10 d after admission.Citation7 A summary of all the cases is presented in .

Table 1. A summary of all cases of varicella from vaccine strain which ended with death.

Risk factors for severe varicella infection in both wild and vaccine type include immunosuppression drug-induced or primary T cell or HIV induced.Citation8

Our patient was diagnosed with congenital asplenia and was under prophylactic treatment with Amoxicillin with good compliance; this condition although explains well the pneumococcal sepsis, but as far as it is known, does not explain the varicella infection. Interestingly, the pneumococcal sepsis developed within 24 hours of MMRV vaccine.

The patient newborn blood spot testing performed was negative for severe combined immunodeficiency (measured by T-cell receptor excision circles [TREC] analysis). Although this result does not exclude immunodeficiencies with normal T-cell counts or impaired functional T cells, the patient was not suspected to have underlying immunodeficiency. In fact, the patient maintained weight on the 20th percentile during her first year of life, did not have a history of recurrent infections and sustained normal lymphocyte counts throughout hospital stay (1.4–3.6 K/μl). Furthermore, the patient was under regular follow up by an immunologist since infancy who according to her expert opinion and based on the patient’s history and previously mentioned testing, there was no need for further investigations to look for underlying immunodeficiencies.

The patient was initially hospitalized due to septic shock, which can impair the immune system function by several recognized immunosuppressive mechanisms that occur during the cytokine storm including loss of CD4 and CD8 cells.Citation9

In addition, it is well established that malnutrition is associated with impaired immune responses in several mechanisms. Of particular interest are the reduced levels of antibodies following vaccinations and the impact of severe malnutrition on T cell function.Citation10 Although the patient did not suffer from malnutrition or failure to thrive prior to her hospitalization, she demonstrated some level of malnutrition during her PICU stay, reflected primarily by low albumin levels (2.5–3.3 g/dl).

Finally, our patient was treated with hydrocortisone in a dosage equivalent to 2 mg/kg/day Prednisone and then lowered to maintenance doses for overall 25 d. Varicella rash appeared one day after treatment was stopped. In fact, it is well known that the risk of severe varicella is especially high when corticosteroids are administered during the incubation period.Citation1 Simultaneous steroid treatment might have posed a great contribution to the development of varicella infection in this patient.

It is worth to notice that purpura fulminans described in our patient was presented on admission, yet the timing of its manifestation was related to the pneumococcal sepsis and it occurred much before the varicella infection.

Furthermore, the patient was on chronic treatment with acetylsalicylic acid due to her cardiac condition. Although it is a rare condition with the current recommendation not to use salicylate-containing compounds (e.g. Aspirin) for children with varicella, Reye syndrome may follow varicella.Citation1 After acquiring varicella infection, no evidence of hepatic failure or encephalopathy was described in our patient. Her severe clinical status and deterioration started at her admission and were primarily related to severe septic shock.

Conclusions

In this report, we present an unusual case of varicella infection with a vaccine strain VZV that is not associated with the typical risk factors known in the literature. Although varicella vaccinations benefit overshadows its side effects and the risk of vaccine strain VZV infection, caution should be taken when patients who receive this vaccine, are hospitalized, malnourished, suffer from sepsis, or treated with steroids. High index of suspicion should be raised when such a patient develops a vesicular rash after vaccination and prompt Acyclovir therapy should be started upon receiving positive lesions results.

Disclosure of potential conlficts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest to disclose and no financial honorarium, grant, other form of payment, or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

References

- Varicella-Zoster Virus Infections | Red Book® 2018 | red Book Online | AAP Point-of-Care-Solutions. [accessed 2020 Feb 19]. https://redbook.solutions.aap.org/chapter.aspx?sectionid=189640215&bookid=2205.

- Marin M, Meer HC, Seward JF. Varicella prevention in the United States: A review of successes and challenges. Pediatrics. 2008;122(3):e744–e751. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-0567.

- Leung J, Marin M. Update on trends in varicella mortality during the varicella vaccine era—United States, 1990–2016. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2018;14(10):2460–63. doi:10.1080/21645515.2018.1480283.

- Social P, Trajectories S. Severe varicella in persons vaccinated with varicella vaccine. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2017;38(3):1–22. doi:10.1177/0164027515620239.Perceived.

- Woodward M, Marko A, Galea S, Eagel B, Straus W. Varicella virus vaccine live: A 22-year review of postmarketing safety data. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6(8):1–13. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofz295.

- Dowell SF, Bresee JS. Severe varicella associated with steroid use. Pediatrics. 1993;92(2):223–228.

- Schrauder A, Henke-Gendo C, Seidemann K, Sasse M, Cario G, Moericke A, Schrappe M, Heim A, Wessel A. Varicella vaccination in a child with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Lancet. 2007;369(9568):1232. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60567-4.

- Sartori AMC. A review of the varicella vaccine in immunocompromised individuals. Int J Infect Dis. 2008;122(3):e744–e751. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-0567.

- Hotchkiss RS, Monneret G, Payen D. Immunosuppression in sepsis: a novel understanding of the disorder and a new therapeutic approach. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(3):260–68. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70001-X.

- Keusch GT. Nutritional Effects on Response of Children in Developing Countries to Respiratory Tract Pathogens: implications for Vaccine Development. Clin Infect Dis. 1991;13(Supplement_6):S486–S491. doi:10.1093/clinids/13.Supplement_6.S486.