ABSTRACT

In Japan, government support for human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination began in November 2010. However, the mass media repeatedly reported on severe adverse events. The Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare suspended proactive recommendations for HPV vaccines in June 2013. Japan’s HPV vaccination rate dropped from 70% to less than 1% in 2017.

We examined cervical cancer screening results in terms of abnormal cytology, histology, and HPV vaccination status among 11,903 women aged 20 to 25 y in the fiscal year 2015. The overall rate of HPV vaccination was 26.1% (3,112/11,903). Regarding cytology, the rate of atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US) or worse was 3.3% (103/3,112) in women who received HPV vaccination (vaccine (+) women) and 5.6% (496/8,791) in women who did not (vaccine (-) women). The rate of high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) or worse was 0.26% (8/3,112) in vaccine (+) women and 0.81% (72/8,791) in vaccine (-) women. Regarding histology, the rate of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 1 or worse (CIN1+) was 1.4% (42/3,112) in vaccine (+) women and 2.1% (178/8,791) in vaccine (-) women. The rates of CIN2+ and CIN3+ were similar regardless of vaccination. We found a significantly lower incidence of CIN in vaccine (+) women. These results suggest that the resumption of recommending HPV vaccination as primary prevention for cervical cancer is needed in Japan.

1. Introduction

Cervical cancer is the second most common cancer among women living in less developed regions, with an estimated 445,000 new cases in 2012. Approximately 270,000 women die from cervical cancer globally each year. More than 85% of these deaths occur in low-income or middle-income countries.Citation1 Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination and cytological cervical cancer screening have been the basis for substantial reductions in cervical cancer incidence and mortality in most high-income countries over the last few decades. Despite being a developed country, Japan continues to have a high cervical cancer mortality rate. In Japan, cervical cytology screening once every 2 y has been recommended since 1983, which has been effective in reducing the mortality rate. However, the incidence of cervical cancer has been increasing since the mid-1990s, especially among women in the 15–39 age group. In Japan, after the licensing of a bivalent HPV vaccine in October 2009 and a quadrivalent HPV vaccine in July 2011, the rate of HPV vaccination was steadily improving in accordance with the vaccine program. The National Immunization Program initiated and funded the use of vaccination as primary prevention for cervical cancer caused by HPV in April 2013. In Japan, HPV vaccination was recommended for 12- to 16-y-olds. This age range was based on the idea that it is better to receive the HPV vaccine before the start of sexual activity and data suggesting that approximately 50% of Japanese women have had their first sexual experience by the age of 18.Citation2 Unfortunately, several adverse incidents after HPV vaccination led to the suspension of the program. On June 14, 2013, the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (MHLW) suspended proactive recommendation of the HPV vaccination program based on sensational media reports without scientific evidence or medical investigations. In other words, in Japan, HPV vaccination had declined dramatically in just 43 months. The law means that HPV vaccines are subject to vaccination recommendations but many individuals have not been vaccinated for the 7 y after the change. In addition, since catch-up inoculation is not covered by public assistance, the number of vaccine recipients is very small because those who wish to be vaccinated will bear the cost. For women born between 1994 and 1999, the HPV vaccination rate was approximately 70%. Currently, the HPV vaccine coverage rate has dropped to less than 1%, according to MHLW in 2017. Since the HPV vaccination rate was high for only a limited age group in Japan, cervical cancer screening results from this group could represent the effect of HPV vaccination.

In this study, we analyzed cervical cancer screening results from 2015 to 2016 for women between the ages of 20 to 25 y, who were aged 12 to 16 y when the HPV vaccination program was recommended, to examine the effect of HPV vaccination on cervical lesions.

2. Materials and Methods

The subjects were women aged 20–25 y who underwent cervical cancer screening in the prefectures of Chiba, Hokkaido, Miyagi, Tokushima, Yamanashi, and Niigata, and the municipalities of Oyama and Izumo from January 2015 to December 2016. We asked participants to self-report vaccination status in a questionnaire. We also asked about the history of HPV vaccination and for consent to use cervical cancer screening results (cervical cytology and histology) for research purposes.

This study defines cytological results as gradually worsening lesions in the order of negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy (NILM), atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US), atypical squamous cells, cannot exclude high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (ASC-H), low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL), high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL). We analyzed the cumulative number of abnormal results for each stage and differences in the cumulative number of abnormal results by vaccination status.

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Japan Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists in 2017 (approval number 202).

Statistical analysis

All data analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 22 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA, https://www.ibm.com/support/pages/how-cite-ibm-spss-statistics-or-earlier-versions-spss). Before statistical analyses, HPV pathology of the vaccinated and unvaccinated groups was compared. HPV pathology was categorized into nine groups: NILM; ASC-US; ASC-H; LSIL; HSIL; squamous cell carcinoma (SCC); atypical glandular cells, adenocarcinoma; and other malignancies. The effect of HPV vaccination was analyzed by pathology category: ASC-US or worse versus NILM, ASC-H or worse versus ASC-US or better, LSIL or worse versus ASC-H or better, and HSIL or worse versus LSIL or better. The chi-squared test was used to compare HPV vaccination status among patients in each HPV pathology category. A value of P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

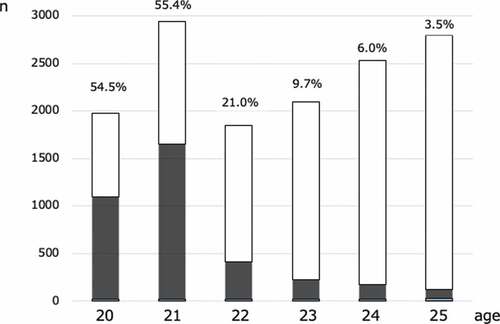

A total of 14,043 women aged 20–25 y underwent cervical cancer screening. In this study, we analyzed the effect of HPV vaccination based on 11,903 cases. We excluded 2,140 cases that lacked cytological results, which included 3,544 (25.2%) women who received HPV vaccination. Vaccination rates were 54.5%, 55.4%, 21.0%, 9.7%, 6.0%, and 3.5% in women aged 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, and 25 y, respectively ().

Regarding cytology, ASC-US occurred in 1.9% of participants (228/11,903), ASC-H in 1.6% (20/11,903), LSIL in 2.2% (271/11,903), HSIL in 6.7% (80/11,903), and SCC in 0% (0/11,903) (). shows the percentage of participants by cytology result. ASC-US or worse occurred in 3.3% (103/3,112) of women with HPV vaccination and 5.6% (496/8,788) in women without HPV vaccination, representing a 41.1% reduction. ASC-H or worse occurred in 1.8% (57/3,112) of women with HPV vaccination and 3.5% (314/8,788) of women without HPV vaccination. LSIL or worse occurred in 1.7% (56/3,112) of women with HPV vaccination and 3.3% (295/8,788) of women without HPV vaccination. HSIL or worse occurred in 0.26% (8/3,112) of women with HPV vaccination and 0.81% (72/8,788) of women without HPV vaccination. For every pathology category, HPV vaccination resulted in a significantly lower rate: ASC-US or worse (P < .0001), ASC-H or worse (P < .0001), LSIL or worse (P < .0001), and HSIL or worse (P < .0001) ().

Table 1. Comparison of cytological results between vaccined and unvaccined

Regarding histology, there were 29 cases of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN)1, 10 cases of CIN2, and 3 cases of CIN3 among women with HPV vaccination. There were 136 cases of CIN1, 28 cases of CIN2, and 14 cases of CIN3 among women without HPV vaccination. The rate of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 1 or worse (CIN1+) was 1.4% (42/3,102) in women with vaccination and 2.1% (178/8,611) in women without vaccination. The rate of CIN2+ was 0.42% (13/3,102) with vaccination and 0.49% (42/8,611) without vaccination. The rate of CIN3+ was 0.096% (3/3,102) with vaccination and 0.163% (14/8,611) without vaccination. The incidence of CIN1+ was significantly lower in the group with HPV vaccination than in the non-vaccinated group (P < .01). However, there were no significant differences in the incidence of CIN 2+ or CIN 3+ by HPV vaccination status ().

Discussion

This study was conducted in eight facilities across eight regions of Japan. These eight facilities were in urban and rural areas, making them a representative sample of Japan. The comparison of cervical cancer screening results and HPV vaccination history showed that HPV vaccination is correlated with lower rates of ASC-US to HSIL in young women. At its peak, the Japanese HPV vaccination rate was 81.1% and 81.2% for women born in 1996 and 1997, respectively; however, the HPV vaccination rate dropped to less than 1% in 2017.

Cytological results differed by HPV vaccination status. In Japan, not many cervical lesions are observed in women in their early 20s. Since the number of HSIL/CIN3+ cases were originally small, differences in the number of patients with advanced lesions by vaccination were small, which might be why no difference in CIN2+ or CIN3+ status by vaccination status was observed. In addition, there was a limit to the data that can be collected because of the retrospective nature of this study. Precise estimates of the effect of vaccination cannot be confirmed unless cytological examination results and tissue diagnosis results by age are available, or the age of the subjects is tracked, and the occurrence of cervical lesions is observed.

The HPV vaccination rate dropped sharply in Japan because the Japanese government has refrained from actively recommending HPV vaccination after alleged adverse post-vaccination incidents. This study investigated the results of pathological examinations among Japanese women who underwent HPV vaccination. Although the study is limited, only Japan cannot leave cervical cancer outbreaks or deaths without HPV vaccination. We expect that this research result will provide information about the importance of HPV vaccination to Japanese individuals.

Research on the effectiveness of HPV vaccines has been reported internationally. Several clinical trials have shown the positive effects of quadrivalent HPVCitation3 and bivalent HPV vaccines.Citation4 The Future II Study followed a randomized, double-blinded trial for 3 y after the initiation of HPV vaccination. An analysis of data from the Future II study comparing 5,305 women in the vaccine group and 5,260 in the placebo group revealed that the vaccine group had a significantly lower incidence of high-grade CIN related to HPV-16 or HPV-18 than the placebo group.Citation3 A study in AustraliaCitation5 showed a 43% decrease in atypical squamous cells and HSIL in women aged 22–25 y at 7 y after three vaccinations. Similarly, in Denmark, a study based on cervical cancer screening results of women aged 20–21 yCitation6 showed that the rate of atypical squamous cells, CIN2, and CIN3 decreased by approximately 60%, 73%, and 80%, respectively. In Scotland, another reportCitation7 also showed that CIN3 decreased by approximately 55% after vaccination. In Europe and the United States, the effectiveness of nonavalent HPV vaccines has been reported. In the hypothetical absence of cervical screening and assuming lifelong protection, 9vHPV vaccination was estimated to reduce lifetime cervical cancer and mortality risks by seven-fold, with a residual lifetime cancer risk ranging from 1/572 (UK) to 1/238 (Denmark) and mortality risk ranging from 1/1,488 (UK) to 1/851 (Denmark). After decades of repeated cervical screening, lifetime cervical cancer and mortality risks were reduced between two-fold to four-fold, depending on the country.Citation8

The World Health Organization Global Advisory Committee for Vaccine Safety concluded that the available evidence does not suggest any safety concerns with the use of HPV vaccines. In 2017, the Vaccine Adverse Effects Review Committee of the Japanese MHLW investigated alleged adverse symptoms such as chronic pain in women after HPV vaccination. Their findings indicated that 8.68/100,000 vaccinated women had symptomsCitation9 (https://www.mhlw.go.jp/bunya/kenkou/kekkaku-kansenshou28/dl/hpv180118-info01.pdf). A study in Nagoya showed that the adverse events were not caused by HPV vaccination. That study was based on an anonymous questionnaire-based survey to determine whether adverse events are related to HPV vaccination with 71,177 female residents of Nagoya as participants. It investigated the onset of 24 symptoms (primary outcome), associated hospital visits, frequency, and influence on school attendance. No significant increase in the occurrence of any of the 24 symptoms was observed after HPV vaccination.Citation10 The results suggest no causal association between HPV vaccination and reported symptoms. There was concern about the credibility of the data because it was based on questionnaires.Citation9 The status of HPV vaccination in this study was based on self-report. Some are concerned about the accuracy of self-reporting.Citation11 Researchers in Niigata, Japan compared the accuracy of self-reported vaccination status with the official municipal records and found that the validity of the self-reported information was only moderate. Since the study in Niigata also used self-reported information, data accuracy could be a concern. It is necessary to cross-check the self-reported information with government records. We are concerned that this study may not be accurate because it was based on a questionnaire about HPV vaccination.

The preventive effects of HPV vaccines have been recognized in most developed countries. However, due to a lack of advocacy, Japan has the lowest HPV vaccination rate. With 10,000 new cases of cervical cancer and 3,000 women dying each year from cervical cancer, implementation of preventative measures is urgently needed. We hope that this study will be used as information to encourage HPV vaccination. We urge the Japanese MHLW to restart the proactive recommendation for HPV vaccination as soon as possible based on scientific evidence.

Limitation

This study was based on common data items collected during non-standardized cervical cancer screening in Japan. In addition to the unpopularity of HPV vaccination in Japan, the rate of cervical cancer screening is low, approximately 30%, and the rate of detailed examination after cytological examination is even lower. Therefore, there were insufficient data available on histological diagnosis to confirm abnormalities detected with the cytological examination. We would like to improve the methods to check for cytological abnormalities and gather accurate data on HPV vaccination status by age, which are not available at this time.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kurman RJ, Carcangiu ML, Herrington CS, Young RH. WHO classification of tumors of female reproductive organs. Lyon, France: International Agency for Reserch on Cancer; 2014.

- Inoue M, Sakaguchi J, Sasagawa T, Tango M. The evaluation of human papillomavirus DNA testing in primary screening for cervical lesions in a large Japanese population. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006;16(3):1007–13. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00460.x. PMID: 16803477.

- Manini I, Montomoli E. Epidemiology and prevention of human Papillomavirus. Annali di igiene: medicina preventiva e di comunita. 2018;30(4Supple 1):28–32. doi:10.7416/ai.2018.2231. PMID: 30062377.

- Prophylactic efficacy of a quadrivalent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine in women with virological evidence of HPV infection. J Infect Dis. 2007;196(10):1438–46. doi:10.1086/522864. FUTURE II Study Group. PMID: 18008221.

- Paavonen J, Naud P, Salmeron J, Wheeler CM, Chow SN, Apter D, Kitchener H, Castellsague X, Teixeira JC, Skinner SR, et al. Efficacy of human papillomavirus (HPV)-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine against cervical infection and precancer caused by oncogenic HPV types (PATRICIA): final analysis of a double-blind, randomised study in young women. Lancet. 2009;374(9686):301–14. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61248-4. PMID: 19586656.

- Crowe E, Pandeya N, Brotherton JM, Dobson AJ, Kisely S, Lambert SB, Whiteman DC. Effectiveness of quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine for the prevention of cervical abnormalities: case-control study nested within a population based screening programme in Australia. BMJ. 2014;348:g1458. doi:10.1136/bmj.g1458. PMID: 24594809.

- Baldur-Felskov B, Dehlendorff C, Munk C, Kjaer SK. Early impact of human papillomavirus vaccination on cervical neoplasia–nationwide follow-up of young Danish women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(3):djt460. doi:10.1093/jnci/djt460.

- Pollock KG, Kavanagh K, Potts A, Love J, Cuschieri K, Cubie H, Robertson C, Cruickshank M, Palmer TJ, Nicoll S. Reduction of low- and high-grade cervical abnormalities associated with high uptake of the HPV bivalent vaccine in Scotland. Br J Cancer. 2014;111(9):1824–30. doi:10.1093/jnci/djt460. PMID: 24552678.

- Petry KU, Bollaerts K, Bonanni P, Stanley M, Drury R, Joura E, Kjaer SK, Meijer CJLM, Riethmuller D, Soubeyrand B, et al. Estimation of the individual residual risk of cervical cancer after vaccination with the nonavalent HPV vaccine. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14(7):1800–06. doi:10.1080/21645515.2018.1450125. PMID: 29553886.

- Suzuki S, Hosono A. No association between HPV vaccine and reported post-vaccination symptoms in Japanese young women: results of the Nagoya study. Papillomavirus Res (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2018;5:96–103. doi:10.1016/j.pvr.2018.02.002. PMID: 29481964.

- Yamaguchi M, Sekine M, Kudo R, Adachi S, Ueda Y, Miyagi E, Hara M, Hanley SJB, Enomoto T. Differential misclassification between self-reported status and official HPV vaccination records in Japan: implications for evaluating vaccine safety and effectiveness. Papillomavirus Res (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2018;6:6–10. doi:10.1016/j.pvr.2018.05.002. PMID: 29807210.