?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

How countries, particularly low- and middle-income economies, should pay the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccine is an important and understudied issue. We undertook an online survey to measure the willingness-to-pay (WTP) for a COVID-19 vaccine and its determinants in Indonesia. The WTP was assessed using a simple dichotomous contingent valuation approach and a linear regression model was used to assess its associated determinants. There were 1,359 respondents who completed the survey. In total, 78.3% (1,065) were willing to pay for the COVID-19 vaccine with a mean and median WTP of US$ 57.20 (95%CI: US$ 54.56, US$ 59.85) and US$ 30.94 (95%CI: US$ 30.94, US$ 30.94), respectively. Being a health-care worker, having a high income, and having high perceived risk were associated with higher WTP. These findings suggest that the WTP for a COVID-19 vaccine is relatively high in Indonesia. This WTP information can be used to construct a payment model for a COVID-19 vaccine in the country. Nevertheless, to attain higher vaccine coverage, it may be necessary to partially subsidize the vaccine for those who are less wealthy and to design health promotion materials to increase the perceived risk for COVID-19 in the country.

Introduction

The current global pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a major international threat.Citation1 More than 10 million confirmed cases have been reported with more than a half million deaths globally.Citation2 In Indonesia, more than 100 thousand confirmed cases and 5,000 deaths have been reported as of August 13, 2020.Citation2 As a response to the pandemic, over 500 clinical trials to assess the efficacy and safety of candidate interventions have been registered in international clinical trial registry platforms.Citation3 Apart from effective treatments, the development of vaccines is a priority to mitigate the pandemic, according to the WHO Research and Development Blueprint.Citation4 Currently, more than 100 vaccine candidates are in the development pipeline.Citation5 The first vaccine candidate entered a Phase 1 clinical trial on March 16, 2020,Citation6 and as of April 9, 2020, five candidates had entered Phase 1 clinical trials.Citation5 On June 13, results of the first phase 1 clinical trial of a COVID-19 vaccine candidate, the Ad5 vectored vaccine, were released and found that the vaccine is tolerable and the humoral responses against SARS-CoV-2 peaked at d 28 post-vaccination.Citation7 Given this accelerated speed of vaccine development, a COVID-19 vaccine might be available in the near future.Citation8

Even with a safe and efficacious COVID-19 vaccine, it is not clear that individuals will accept and purchase the vaccine. Therefore, it is important to evaluate acceptance and willingness-to-pay (WTP) for a vaccine. Assessment of WTP, defined as the maximum amount of money that individuals would be willing to pay for a vaccine, not only determines the potential market but also obtains information to be incorporated in formulating the best payment strategy for a new vaccine. WTP is influenced by many factors including sociodemographic characteristics as well as preexisting attitudes and beliefs of individuals.Citation9–13 These characteristics do not necessarily have consistent relationships with WTP across communities.Citation9 Therefore, identification of determinants associated with WTP for COVID-19 is also key for the government and other organizations to develop a well-designed intervention program for use in key populations. This is crucial in particular to achieve high COVID-19 vaccine coverage especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) which may not have the fiscal capacity to fully subsidize the vaccine for every resident.

Studies assessing acceptance and WTP of a COVID-19 vaccine are limited. A previous study has assessed preferences for COVID-19 vaccination in China among health-care workers but this study did not assess the WTP.Citation14 A study in Romania was conducted to assess the WTP for COVID-19 vaccine candidate and found that the acceptable price range of the vaccine was between 20 and 200 EUR (equivalent with US$ 23.63 and 236,18, respectively, using an August 2020 exchange rate 1 EUR = US$ 1.18).Citation15 In a recent study in Chile, WTP for a COVID-19 vaccine was approximately US$184.Citation16 In southeast Asia, the only available data were generated from a study in Malaysia.Citation17 The study found that the mean WTP for a dose of COVID-19 vaccine was US$ 30.66.Citation17 To add more information in the literature, we undertook a study in Indonesia. This study’s main objective was to determine how much money members of the general community would be willing to pay for a COVID-19 vaccine when it is available (i.e. WTP) and to assess the associated determinants with this WTP.

Since there is no available COVID-19 vaccine, a hypothetical vaccine approach was adopted as has previously used for new vaccines against dengue,Citation9,Citation10,Citation12 Ebola,Citation18–21 chikungunya,Citation20 Zika,Citation22,Citation23 and COVID-19.Citation15,Citation16 To estimate the WTP, the contingent valuation approach was adopted. This method has been used to estimate WTP for many hypothetical vaccines such as against dengue,Citation11,Citation24,Citation25 Zika,Citation22,Citation23 HIV,Citation26 rabiesCitation27 as well as COVID-19Citation16 since it is able to calculate a precise WTP with its confidence interval with relatively high statistical power.Citation16,Citation28 With the current escalating pandemic and its massive impact on the global economy,Citation29 these results will be important in formulating a COVID-19 vaccine financing when it is available not only in Indonesia but also in other countries in the region.

Methods

A cross-sectional online survey was conducted in the general population of Indonesia between March 25 and April 6, 2020. The mode of an online survey was chosen due to the difficulty in doing a face-to-face study amid the ongoing COVID-19 outbreak. The target population in this study was the adult population who were able to read and understand the national language Bahasa Indonesia. Using a simplified snowball sampling technique, sample recruitment was conducted among community members in six provinces (Aceh, Bali, DKI Jakarta, Jambi, West Sumatra, and Yogyakarta) out of 34 provinces in the country. Participants were asked about a hypothetical vaccine, using an approach applied in previous studies.Citation9,Citation10,Citation12,Citation15,Citation16,Citation18–23

Invitations with a link to complete a 10 min long survey, hosted by Google Forms, were distributed through the WhatsApp communication platform as a direct message. Those who were directly invited to participate were also requested to pass the invitations to their WhatsApp contacts. WhatsApp was chosen since a majority of Indonesians (64%) across sociodemographic characteristics use this platform. Therefore, it enabled us to reach the general population both from high and low socioeconomic status, which is critical for WTP studies.

Prior to participating in the survey, a potential participant was first shown a webpage that contained brief information about the study and the aims of the study, estimated completion time, the identity of the principal investigators, contact details, and collaborating institutions. At the end of the page, an informed consent document was provided and individuals had to agree by checking a checkbox “Yes” before they could proceed to the survey. During the survey, no electronic signatures were required and the IP addresses of participants were not collected. To ensure confidentiality, only the principal investigators had access to the survey account. The potential participants were informed that they could exit the survey at any point, but that existing responses would still be recorded. At the end of the survey period, the data were extracted from the survey host and imported into statistical software for analysis. The survey was voluntary and no incentive was offered.

A set of questions was developed to assess WTP and to collect a range of potential determinants such as sociodemographic data, monthly income, exposure to COVID-19 information, and perceived risk of being infected with SARS-CoV-2. Prior to the actual study, the questions were tested in a small pilot study and were finalized based on feedback.

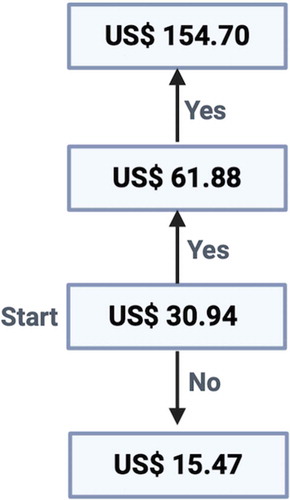

The response variable in this study was WTP for a COVID-19 vaccine. To evaluate WTP, it was hypothesized that a COVID-19 vaccine had been developed and tested in the clinical trials in human and showed a 95% efficacy to prevent COVID-19 in nonimmune population with a 5% chance to produce of a mild adverse effect such as pain on the skin, skin rash and fever. No information about dosing was provided. A simple dichotomous contingent valuation approachCitation25 was used with modification in which no open-ended questions were provided. Participants were first asked if they would accept a COVID-19 vaccine. If yes, they were asked about WTP. The first bid was Indonesian Rupiah (IDR) 500,000 (equivalent with US$ 30.94 using an April 2020 exchange rate of 1 US$ = IDR 16,159.80). Then, the bid was either doubled to IDR 1 million (US$ 61.88) with the highest bid was 2.5 million (US$ 154.70) or halved to IDR 250.000 (US$ 15.47) (). The lowest and the highest price provided were US$ 15.47 and US$ 154.70, respectively. The possible responses for each bit were “yes” or “no.” A participant who refused to pay at the lowest bid (i.e. US$ 15.47) was considered not willing to pay. The WTP for each participant was defined as the maximum amount of money that participants would be willing to pay (i.e. the highest bid where the participant responded “yes”).

Some determinants such as sociodemographic characteristics, preexisting exposure to COVID-19 information, and perceived risk were collected. Sociodemographic characteristics included age, gender, educational attainment, occupation, religion, marital status, individual monthly income, and whether the participant resided in an urban or rural area. Monthly income was grouped into: (a) less than IDR 2.5 million (<US$ 154.70); (b) IDR 2.5–5 million (US$ 154.70–US$ 309.41); (c) IDR 6–10 million (US$ 371.29–US$ 618.81); and (d) more than IDR 10 million (>US$ 618.81). Perceived risk, defined as the perceived risk of contracting COVID-19 within the next month, was assessed on a scale from 0% to 100% as explained previously.Citation30

A linear regression model was used to assess determinants associated with WTP as described previously.Citation9,Citation18,Citation23 Diagnostic assessments were carried out to assess multicollinearity, heteroscedasticity, and residual normality.Citation9,Citation23 The Variance Inflation Factor (VIF)Citation31 was used to assess the multicollinearity and a VIF lower than 10 and tolerance value (1/VIF) of greater than 0.1 were used as a cutoff point to indicate that there was no multicollinearity between determinants. Heteroscedasticity and residual normality assumptions were checked using Glejser testCitation32 and Kolmogorov–Smirnov test,Citation33 respectively. A p-value greater than 0.05 in the Glejser and Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests indicated that the residuals have a constant variance (homoscedasticity), and distributed normally. Since the initial assessment indicated the WTP response data violated heteroscedasticity and normality of residual assumptions, the data were then transformed using a natural logarithm function (ln).

With a log-transformation of the outcome, the WTP data were then on a ratio scale, which is widely accepted and used in previous vaccine studies.Citation9,Citation18,Citation23,Citation27,Citation34,Citation35 We calculated the 95% confidence interval (CI) for each independent variable. For a determinant measured in categorical variables, one of the categories was designated as the reference category. In the initial model, all determinants were included and all determinants with p < .05 in this model were entered the final model.

The mean of the estimated WTP was calculated as described previously.Citation9,Citation23 The mean of the estimated WTP was calculated as described previously.Citation9,Citation23 The mean of the estimated WTP was calculated in US$ as where the

and

were estimated regression coefficients and the mean squared error (MSE) of the regression model, respectively.Citation36,Citation37

Results

During the study period, 1,359 respondents completed the survey. Of the total, 91 (6.6%) would reject the vaccine even if it was provided freely, and 203 (14.9%) stated that they would like to be vaccinated only if the vaccine was provided for free, leaving 1,065 (78.3%) participants willing to pay for a vaccine and included in the WTP analysis. The characteristics of those who were willing to pay for the vaccine are provided in . More than half (53.1%) of the participants were aged 21–30 y old, the majority (68.5%) were females, and more than two-third graduated from a university. Almost half earned less than US$ 123.76 a month and most of the respondents (78.4%) lived in cities. Although the vast majority (98.8%) of participants stated that they had heard about COVID-19 prior to the study, 35.1% perceived a 0% risk to be infected within the next month.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of participants who were willing to pay for a COVID-19 vaccine in Indonesia (n = 1,065)

The mean and median WTP was US$ 57.20 (95%CI: US$ 54.56, US$ 59.85) and US$ 30.94 (95%CI: US$ 30.94, US$ 30.94), respectively. Among total participants, 78.4% (1065/1359), 55.4% (753/1359), 34.4% (468/1359), and 21.8% (296/1359) of them were willing to pay when the vaccine price US$ 15.47, US$ 30.94, US$ 61.88, and US$ 123.76, respectively. Among participants who were willing to pay, 29.3% (312/1065) were willing to pay only US$ 15.47. This percentage decreased to 26.7% (285/1065), 16.1% (172/1065), and 27.7% (296/1065) as the price increased to US$ 30.94, US$ 61.88, and US$ 123.76, respectively.

Our initial, unadjusted linear regression model indicated that working as HCWs, religion, individual monthly income, and perceived risk were associated with changes in WTP (). Our final, multivariable model revealed that all of those determinants were also associated with changes in WTP with monthly income being the strongest determinant of WTP change (). HCWs had a higher WTP of approximately US$ 1.62 compared to non-HCW and participants who identified themselves as Catholics had higher WTP compared to Moslems, approximately US$ 2.08 (). Compared to respondents who earned less than US$ 154.70, participants who belong to higher income groups (US$ 154.70–US$ 309.41; US$ 371.29–US$ 618.82, and >US$ 618.81) also had higher WTP, approximately US$ 1.84, US$ 2.01, and US$ 2.82, respectively. Participants whose perceived risk was more than 60% had higher WTP (US$ 1.84) compared to those who believed that they would not be infected.

Table 2. Initial multivariable linear regression model showing factors associated with the willingness-to-pay for a COVID-19 vaccine in Indonesia (n = 1,065)

Table 3. Final multivariable linear regression model showing factors associated with the willingness-to-pay for a COVID-19 vaccine in Indonesia (n = 1,065)

Discussion

It is not clear what the price of the COVID-19 vaccine will be, when it becomes available, but since COVID-19 is a pandemic that is impacting all countries, the vaccine is likely to receive public subsidies. Countries with limited resources will have to develop a payment scheme that balances costs and benefits. This optimal price will depend on the dynamics of what proportion of the community will accept the vaccine and how much they are willing to pay for the vaccine.

Our study demonstrated that a vast majority of Indonesian adults responding to our survey were willing to obtain and pay for a COVID-19 vaccine and only a small fraction of 6.6% (91/1,359) were not willing to be vaccinated. However, among those who were willing to be vaccinated, 16.1% (203/1260) expressed that they were not even willing to pay US$ 15.47. This suggests that if the vaccine price will be higher than US$ 15.47 (IDR 250,000), one-fifth of the population, at least, in studied provinces may not become vaccinated. This could lead to problems attaining herd immunity. Currently, it is estimated that perhaps 60% of individuals need to be immune to attain herd immunity,Citation38 but with an imperfectly effective vaccine, that would mean an even larger proportion of the population would need to be vaccinated. With our study results, it is doubtful that herd immunity through vaccination could be obtained without financial subsidies to vaccination.

Our study found that monthly income is the strongest predictor for a positive WTP change, and this relationship has been demonstrated previously.Citation10,Citation12,Citation23,Citation39–41 This may reflect a direct correlation between WTP and ability to pay, or an indirect correlation that those with higher income may have a greater understanding of the benefit of vaccination. To be more explicit in the relationship between income and WTP, knowledge of participants about the COVID-19 vaccine should be explored. Although our study did not measure participants’ knowledge about COVID-19, the contribution of knowledge toward a higher WTP may be reflected by a higher WTP for a COVID-19 vaccine among HCWs compared to those who were working in non-medical sectors. A previous study also found that HCWs are more supportive of a COVID-19 vaccine than non-HCWs.Citation42 In an outbreak event, HCWs’ awareness of infection control can be a driver in their decision to become vaccinated.Citation43,Citation44

Apart from sociodemographic and socioeconomic status, knowledge of the disease, attitude toward the disease, and attitude toward vaccination are associated with WTP for a new vaccine.Citation9–12 In the context of COVID-19, knowledge of COVID-19, perception of government performance, and COVID-19-related experiences such as being sick with or has recovered from COVID-19 were associated with the WTP.Citation16 In this present study, those factors were not adequately investigated. Nevertheless, our study found that perceived risk for COVID-19 was associated with WTP only when perceived risk was higher than 60% (i.e. the individual believed that there was a > 60% chance to be infected within the next month). This factor should receive more attention since this is the only modifiable determinant for WTP in this study. Previous studies have found that perceived risk or perceived susceptibility is associated with positive vaccination supportCitation13,Citation45 and those with higher perceived risk had greater acceptance for COVID-19 vaccine.Citation42 Well-designed programs to increase perceived risk for COVID-19 might be also necessary to increase a positive attitude for vaccination because this factor is the strongest determinant for acceptanceCitation46 and WTP for a new vaccine.Citation9 It is also important to consider other determinants of vaccine uptake – ease of access, awareness of the vaccine, and nudges can all increase uptake.Citation47

Some limitations of this study need to be discussed. Although this study used the WhatsApp planform to reach those with low income and in the rural area, the generalizability of the results from this study should be done with caution due to sampling bias. In January 2020, internet penetration in Indonesia was approximately 64%,Citation48 but internet infrastructure differences across the country (which are better in cities than rural areas) indicate the possibility of sampling bias.Citation49,Citation50 Based on Statistics Indonesia, in 2019, the national average of individual monthly income in the country was approximately US$ 304.75.Citation51 In the present study, 47% of the respondents had monthly income less than US$ 154.70, and 30.1% earned between US$ 154.70–US$ 309.41 each month suggesting the income of respondent study is relatively lower compared to the estimated national income. This could have an implication that the WTP found in this study might be lower compared to the actual WTP of the general population in Indonesia. Nevertheless, most of the study participants were from urban areas resulting in a low inclusion rate of those with low educational attainment. In Indonesia, rural dwellers generally have less wealth and lower educational attainment. Although we did not observe a significant association between urbanicity or education on WTP, as in previous studies,Citation9,Citation21 this sampling bias may have shifted the observed WTP than in the actual general population. Additionally, in this study, we gave respondents information about a 95% effective vaccine. But the vaccine may prove to have lower effectiveness, which itself could impact acceptanceCitation52 and WTP for the vaccine.

Conclusion

When a very effective COVID-19 vaccine is available, more than 70% of community members in Indonesia likely will be willing to pay for the vaccine with the mean WTP approximately US$ 57. Having higher individual monthly income and higher perceived risk of being infected with COVID-19 are associated with WTP. One important modifiable determinant associated with WTP is the perceived risk of contracting COVID-19, which could be targeted in health promotions. Health promotions could be combined with vaccine price subsidies in order to attain an adequately high vaccination coverage.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Human subjects approval statement

The protocol of the study was approved by Institutional Review Board, Universitas Syiah Kuala (041/EA/FK-RSUDZA/2020), and National Health Research and Development Ethics Commission (KEPPKN) of the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Indonesia (#1171012P).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Synat Keam for assistance in this study.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Harapan H, Itoh N, Yufika A, Winardi W, Keamg S, Te H, Megawati D, Hayati Z, Wagner A, Mudatsir M. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a literature review. J Infect Public Health. 2020;13(5):667–73. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2020.03.019.

- Dong E, Du H, Gardner L. An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(5):533–34. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30120-1.

- Thorlund K, Dron L, Park J, Hsu G, Forrest J, Mills E. A real-time dashboard of clinical trials for COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;2:e286–e287.

- Bedford J, Enria D, Giesecke J, Heymann DL, Ihekweazu C, Kobinger G, Lane HC, Memish Z, Oh MD, Sall AA, et al.; Strategic, W. H. O.; Technical Advisory Group for Infectious, H. COVID-19: towards controlling of a pandemic. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1015–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30673-5.

- Thanh Le T, Andreadakis Z, Kumar A, Gomez Roman R, Tollefsen S, Saville M, Mayhew S. The COVID-19 vaccine development landscape. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2020;19(5):305–06. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/d41573-020-00073-5.

- Lurie N, Saville M, Hatchett R, Halton J. Developing Covid-19 vaccines at pandemic speed. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):1969–73. In press. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2005630.

- Zhu FC, Li YH, Guan XH, Hou LH, Wang WJ, Li JX, Wu SP, Wang BS, Wang Z, Wang L, et al. Safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of a recombinant adenovirus type-5 vectored COVID-19 vaccine: a dose-escalation, open-label, non-randomised, first-in-human trial. Lancet. 2020;395(10240):1845–54. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31208-3.

- Hanney SR, Wooding S, Sussex J, Grant J, From COVID-19. research to vaccine application: why might it take 17 months not 17 years and what are the wider lessons? Health Res Policy Syst. 2020;18(1):61. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-020-00571-3.

- Harapan H, Anwar S, Bustamam A, Radiansyah A, Angraini P, Fasli R, Salwiyadi S, Bastian RA, Oktiviyari A, Akmal I, et al. Willingness to pay for a dengue vaccine and its associated determinants in Indonesia: a community-based, cross-sectional survey in Aceh. Acta Trop. 2017;166:249–56. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2016.11.035.

- Hadisoemarto PF, Castro MC. Public acceptance and willingness-to-pay for a future dengue vaccine: a community-based survey in Bandung, Indonesia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2427.

- Palanca-Tan R. The demand for a dengue vaccine: a contingent valuation survey in Metro Manila. Vaccine. 2008;26(7):914–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.12.011.

- Lee JS, Mogasale V, Lim JK, Carabali M, Sirivichayakul C, Anh DD, Lee KS, Thiem VD, Limkittikul K, Tho Le H, et al. A multi-country study of the household willingness-to-pay for dengue vaccines: household surveys in Vietnam, Thailand, and Colombia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9(6):e0003810. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0003810.

- Rajamoorthy Y, Radam A, Taib NM, Rahim KA, Munusamy S, Wagner AL, Mudatsir M, Bazrbachi A, Harapan H. Willingness to pay for hepatitis B vaccination in Selangor, Malaysia: a cross-sectional household survey. PLoS One. 2019;14(4):e0215125. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0215125.

- Fu C, Wei Z, Pei S, Li S, Sun S, Liu P. Acceptance and preference for COVID-19 vaccination in health-care workers (HCWs). medRxiv Preprint. 2020. doi:https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.09.20060103.

- Berghea F, Berghea CE, Abobului M, Vlad VM. Willingness to pay for a for a potential vaccine against SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 among adult persons; 2020. doi:https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-32595/v1

- Garcia LY, Cerda AA. Contingent assessment of the COVID-19 vaccine. Vaccine. 2020;38(34):5424–29. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.06.068.

- Wong LP, Alias H, Wong P-F, Lee HY, AbuBakar S. The use of the health belief model to assess predictors of intent to receive the COVID-19 vaccine and willingness to pay. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;1–11. In press. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2020.1790279.

- Mudatsir M, Anwar S, Fajar JK, Yufika A, Ferdian MN, Salwiyadi S, Imanda AS, Azhars R, Ilham D, Timur AU. Willingness-to-pay for a hypothetical Ebola vaccine in Indonesia: a cross-sectional study in Aceh. F1000Research. 2019;8(1441):1441. doi:https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.20144.1.

- Ughasoro MD, Esangbedo DO, Tagbo BN, Mejeha IC. Acceptability and willingness-to-pay for a hypothetical ebola virus vaccine in Nigeria. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9(6):e0003838. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0003838.

- Sarmento TTR, Godoi IP, Reis EA, Godman B, Ruas CM. Consumer willingness to pay for a hypothetical chikungunya vaccine in Brazil and the implications. In Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res; 2019. p. 1–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14737167.2020.1703181.

- Painter JE, von Fricken ME, Viana de OMS, DiClemente RJ. Willingness to pay for an Ebola vaccine during the 2014-2016 ebola outbreak in West Africa: results from a U.S. National sample. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14(7):1665–71. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2018.1423928.

- Muniz Junior RL, Godoi IP, Reis EA, Garcia MM, Guerra-Junior AA, Godman B, Ruas CM. Consumer willingness to pay for a hypothetical Zika vaccine in Brazil and the implications. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2019;19(4):473–82. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14737167.2019.1552136.

- Harapan H, Mudatsir M, Yufika A, Nawawi Y, Wahyuniati N, Anwar S, Yusri F, Haryanti N, Wijayanti NP, Rizal R, et al. Community acceptance and willingness-to-pay for a hypothetical Zika vaccine: a cross-sectional study in Indonesia. Vaccine. 2019;37(11):1398–406. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.01.062.

- Yeo HY, Shafie AA. The acceptance and willingness to pay (WTP) for hypothetical dengue vaccine in Penang, Malaysia: a contingent valuation study. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2018;16:60. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12962-018-0163-2.

- Nguyen LH, Tran BX, Do CD, Hoang CL, Nguyen TP, Dang TT, Thu Vu G, Tran TT, Latkin CA, Ho CS, et al. Feasibility and willingness to pay for dengue vaccine in the threat of dengue fever outbreaks in Vietnam. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018;12:1917–26.

- Bishai D, Pariyo G, Ainsworth M, Hill K. Determinants of personal demand for an AIDS vaccine in Uganda: contingent valuation survey. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82:652–60.

- Birhane MG, Miranda ME, Dyer JL, Blanton JD, Recuenco S. Willingness to pay for dog rabies vaccine and registration in Ilocos Norte, Philippines (2012). PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10(3):e0004486. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0004486.

- Boyle J. Contingent valuation in practice. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer; 2017. p. 83–131.

- Boissay F, Rungcharoenkitkul P. Macroeconomic effects of Covid-19: an early review. Bank for International Settlements; 2020 [accessed 17 Jul 2020] https://www.bis.org/publ/bisbull07.pdf.

- Masters N, Shih S, Bukoff A, Akel K, Kobayashi L, Miller A, Harapan H, Lu Y, AL W. Social distancing in response to the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) in the United States; PloS ONE; 2020.

- O’Brien RM. A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Qual Quant. 2007;41(5):673–90. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-006-9018-6.

- Glejser H. A new test for heteroskedasticity. J Am Stat Assoc. 1969;64(325):316. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1969.10500976.

- Yap BW, Sim CH. Comparisons of various types of normality tests. J Stat Comput Simul. 2011;81(12):2141–55. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00949655.2010.520163.

- Sauerborn R, Gbangou A, Dong H, Przyborski JM, Lanzer M. Willingness to pay for hypothetical malaria vaccines in rural Burkina Faso. Scand J Public Health. 2005;33(2):146–50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14034940510005743.

- Hansen KS, Pedrazzoli D, Mbonye A, Clarke S, Cundill B, Magnussen P, Yeung S. Willingness-to-pay for a rapid malaria diagnostic test and artemisinin-based combination therapy from private drug shops in Mukono District, Uganda. Health Policy Plan. 2013;28(2):185–96. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czs048.

- Feng C, Wang H, Lu N, Chen T, He H, Lu Y, Tu XM. Log-transformation and its implications for data analysis. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2014;26:105–09.

- Yang J. Interpreting coefficients in regression with log-transformed variables. Cornell Stat Consulting Unit. 2012. [accessed 1 Mar 2019] https://www.cscu.cornell.edu/news/archive.php

- Lloyd J, Coronavirus: can herd immunity protect us from COVID-19?; 2020 [accessed 14 May 2020] https://www.sciencefocus.com/news/coronavirus-can-herd-immunity-protect-us-from-covid-19/.

- Arbiol J, Yabe M, Nomura H, Borja M, Gloriani N, Yoshida S-I. Using discrete choice modeling to evaluate the preferences and willingness to pay for leptospirosis vaccine. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2015;11(4):1046–56. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2015.1010901.

- Vo TQ, Tran QV, Vo NX. Customers’ preferences and willingness to pay for a future dengue vaccination: a study of the empirical evidence in Vietnam. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018;12:2507–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S188581.

- Harapan H, Anwar S, Ferdian M, Salwiyadi S, Imanda A, Azhars R, Fika D, Ilham D, Timur A, Sahputri J, et al. Public acceptance of a hypothetical Ebola virus vaccine in Aceh, Indonesia: A hospital-based survey. Asian Pac J Trop Dis. 2017;7(4):193–98. doi:https://doi.org/10.12980/apjtd.7.2017D6-386.

- Harapan H, Wagner AL, Yufika A, Winardi W, Anwar S, Gan AK, Setiawan AM, Rajamoorthy Y, Sofyan H, Mudatsir M. Acceptance of a COVID-19 Vaccine in Southeast Asia: A Cross-Sectional Study in Indonesia. Front Public Health. 2020; 8: 381. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00381.

- Vasilevska M, Ku J, Fisman DN. Factors associated with healthcare worker acceptance of vaccination: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35(6):699–708. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/676427.

- Nguyen TTM, Lafond KE, Nguyen TX, Tran PD, Nguyen HM, Ha VTC, Do TT, Ha NT, Seward JF, McFarland JW. Acceptability of seasonal influenza vaccines among health care workers in Vietnam in 2017. Vaccine. 2020;38(8):2045–50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.12.047.

- Rajamoorthy Y, Radam A, Taib NM, Rahim KA, Wagner AL, Mudatsir M, Munusamy S, Harapan H. The relationship between perceptions and self-paid hepatitis B vaccination: A structural equation modeling approach. PLoS One. 2018;13(12):e0208402. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0208402.

- Harapan H, Anwar S, Setiawan AM, Sasmono RT, Aceh Dengue S. Dengue vaccine acceptance and associated factors in Indonesia: A community-based cross-sectional survey in Aceh. Vaccine. 2016;34(32):3670–75. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.05.026.

- Thomson A, Robinson K, Vallee-Tourangeau G. The 5As: A practical taxonomy for the determinants of vaccine uptake. Vaccine. 2016;34(8):1018–24. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.11.065.

- Data portal, digital 2020: Indonesia; 2020. [accessed 14 Jul 2020] https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2020-indonesia.

- Harapan H, Setiawan AM, Yufika A, Anwar S, Wahyuni S, Asrizal FW, Sufri MR, Putra RP, Wijayanti NP, Salwiyadi S, et al. Knowledge of human monkeypox viral infection among general practitioners: a cross-sectional study in Indonesia. Pathog Glob Health. 2020;114(2):68–75. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/20477724.2020.1743037.

- Harapan H, Setiawan AM, Yufika A, Anwar S, Wahyuni S, Asrizal FW, Sufri MR, Putra RP, Wijayanti NP, Salwiyadi S, et al. Confidence in managing human monkeypox cases in Asia: a cross-sectional survey among general practitioners in Indonesia. Acta Trop. 2020;206:105450. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2020.105450.

- Victoria A, Rata-rata Pendapatan Penduduk Indonesia Setahun Rp 59 Juta; 2020. [accessed 14 Jul 2020] https://katadata.co.id/berita/2020/02/05/rata-rata-pendapatan-penduduk-indonesia-setahun-rp-59-juta.

- Harapan H, Wagner AL, Yufika A, Winardi W, Anwar S, Gan AK, Setiawan AM, Rajamoorthy Y, Sofyan H, Mudatsir M. Acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine in southeast Asia: a cross-sectional study in Indonesia. Fronti Public Health. 2020;8:381. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00381.