ABSTRACT

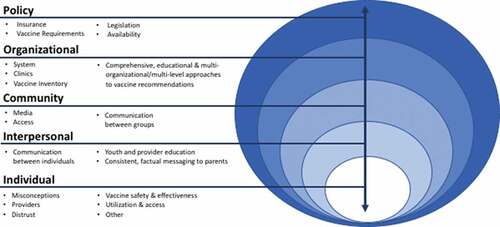

Nationally, human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination rates fall short of the Healthy People 2020 goal of 80% completion. Although strategies to increase these rates exist, low rates persist. We used concept mapping with state-level stakeholders to better understand barriers and facilitators to HPV vaccination. Concept mapping is a participatory research process in which respondents brainstorm ideas to a prompt and then sort ideas into piles. We present results of the brainstorming phase. We recruited participants identified by researchers’ professional connections (n = 134) via e-mail invitations from five states (Iowa, South Dakota, Minnesota, Oregon, and Washington) working in adolescent health, sexual health, cancer prevention and control, or immunization. Using Concept Systems’ online software we solicited participants’ beliefs about what factors have the greatest influence on HPV vaccination rates in their states. From the original sample 58.2% (n = 78) of participants completed the brainstorming activity and generated 372 statements, our team removed duplicates and edited statements for clarity, which resulted in 172 statements. We coded statements using the Social Ecological Model (SEM) to understand at what level factors affecting HPV vaccination are occurring. There were 53 statements at the individual level, 22 at the interpersonal level, 21 in community, 51 in organizational, and 25 in policy. Our results suggest that a tiered approach, utilizing multi-level interventions instead of focusing on only one level may have the most benefit. Moreover, the policy-level influences identified by participants may be difficult to modify, thus efforts should focus on implementing evidence-based interventions to have the most meaningful impact.

Introduction

The human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine offers protection against cancers developed as a result of viral infection.Citation1 The HPV vaccine is now approved up to age 45, however the priority is for adolescents to receive the vaccine between 9 and 12 years old because at this age their immune responses are greatest and they will have protection for many years during which they could be exposed. Currently, if individuals are not vaccinated by the time they are 26, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices suggest a shared-decision making approach between adults and their primary care providers.Citation2 However, despite offering protection against multiple types of cancer, HPV vaccination rates for adolescents remain much lower than the Healthy People 2020 goal of 80% coverage.Citation3 According to 2019 National Immunization Survey data, only 54% of male and female adolescents are fully vaccinated against HPV.Citation4

Within this age group, significant disparities remain in uptake. Males continue to have lower HPV vaccination coverage than their female peers; 56.8% of female are up to date with the series compared to 51.8% of males. Furthermore, a lower rate of coverage for rural adolescents has been a persistent issue with the HPV vaccine.Citation5 Data from the NIS-teen survey shows that while 47.3% of rural adolescents are up to date with the series, urban adolescents have a coverage rate of 57.1%.Citation4 In addition to gender and urban-rural disparities, differing rates of initiation and completion have also been observed between racial and ethnic groups and by insurance status. In an analysis of the NIS-teen data, researchers found that non-Hispanic white teens had the highest rates of non-initiation and that those with Medicaid had higher coverage than adolescents with private insurance.Citation6 We would also be remiss to ignore the fact that the vaccine landscape differs across the globe; there are significant disparities in vaccination rates across the globe as well as in determinants of HPV vaccine uptake.Citation7–9

To eliminate these disparities and promote HPV vaccination nationwide, public health researchers and practitioners have made great strides in developing programming to improve uptake.Citation10–14 Yet, the fact that vaccination rates remain consistently below targets indicates a need for enhanced vaccine promotion strategies. Understanding what factors are still contributing to these low vaccination rates will help to identify specific gaps and areas for future intervention. With this study, we sought to characterize how state-level stakeholders conceptualize these factors that affect HPV vaccination uptake. Focusing on state-level stakeholders allows for a bird’s eye view of the vaccination landscape and leverages this unique position to supply insights into vaccination uptake that may not come from providers or parents who are often the focus of this research. While these stakeholders work at an organizational level, they are also tuned in to what is happening in clinics, communities, and at a policy level, therefore they are able to offer unique insights into this issue.Citation15 Additionally, by working at the state level, these individuals have a wide purview to enact change and to bring together resources and local stakeholders in their areas, therefore increasing their impact on the vaccination landscape.

To collect data from our participants, we used concept mapping, a systematic process to gather and organize information which includes brainstorming, pile sorting, and rating.Citation16 Concept mapping is a participatory research method in which quantitative analysis is used to structure qualitative data.Citation17 The process categorizes responses from participants to show relationships between ideas. This method has been used across a variety of topicsCitation18,Citation19 and populations.Citation20,Citation21 Online concept mapping can be used to gather information from people who are not co-located while still allowing for collaboration.

Finally, we used the Social Ecological Model (SEM), which identifies influences on health at multiple levels (individual, interpersonal, community, organizational, and policy), to code and organize our results. The SEM has been used previously to understand factors related to HPV vaccination uptake as it can help both researchers, practitioners, and stakeholders better understand where to focus their efforts.Citation15,Citation22,Citation23 Identifying at what level barriers or facilitators to vaccination occur will give stakeholders new insights into where to target future vaccine promotion efforts in their respective states While several studies have used SEM to understand state-level stakeholders’ perspectivesCitation15,Citation22 few have used a concept mapping approach that targeted stakeholders in multiple states. Our aim was to utilize online concept mapping to leverage knowledge across states serving rural adolescents and to understand priorities and regional context which can help us improve vaccination rates and translate to a broader audience.

Methods

We conducted a concept mapping project in five states (Iowa, Minnesota, Oregon, South Dakota, and Washington) to assess perceived influences on adolescent HPV vaccination uptake in both rural and urban areas. This project was reviewed by the lead university’s Institutional Review Board and determined to be not human subjects’ research.

Our sample was comprised of stakeholders working in fields of adolescent health, sexual health, cancer prevention and control, and/or immunization whose organizations have state-wide purview. For example, state departments of public health, state immunization coalitions, or organizations like the American Cancer Society. While some of these organizations serve entire state populations, including adults (for example, American Cancer Society), the focus of this project was on their work on adolescent HPV vaccination. Additionally, this data collection took place prior to the change in the ACIP recommendation to include 27 to 45-year-olds. The sample was created based on the research team’s contacts in these fields and internet searches to identify relevant individuals. A total of 134 individuals were sent e-mail invitations to participate in the concept mapping project. We sent e-mail reminders at one and three weeks after the first recruitment e-mail, and then non-participants received follow-up personalized e-mails from a team member in their respective state. Participants received a 20 USD gift card for completion of the brainstorming activity.

We used The Concept System Global MAX, an online concept mapping softwareCitation24 to collect participant responses. Participants responded to the following, focused prompt: What factors do you believe have the greatest influence on HPV vaccination rates in your state? Please provide an exhaustive list and consider both rural and urban regions, as well as both positive and negative influences. Participants were able to enter an unlimited number of statements in the text box.

A total of 78 stakeholders participated in the brainstorming exercise, resulting in a response rate of 58.2%. Participants generated a total of 372 statements. We eliminated statements if they were duplicates, edited all statements for clarity, and in the case that a statement contained multiple ideas, split them as appropriate. This resulted in a final list of 172 statements to code. We developed a codebook using definitions of the levels of the SEM from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.Citation25 To code brainstormed statements by levels of the SEM (individual, interpersonal, community, organizational, and policy), we first generated a random sample (n = 30) of the statements which two research assistants coded independently. Our team then met to discuss discrepancies in coding and refined the codebook, at which point research assistants coded all remaining statements. The full team met a final time to resolve remaining discrepancies in the coding. This meeting included discussions about statements that coders felt fell into two SEM levels. In these cases, we made a collective decision to code each statement at only one level. Within each level of the SEM, our team identified sub-themes and categorized each statement appropriately.

Results

provides characteristics of the respondents and their organizations. We collected information on the type of organization they work for, their area(s) of expertise, and their role in their organization. The respondents represented a range of organizations, although most were from public health organizations, and the majority had expertise in public health or adolescent health. Most of the respondents reported having programming or management roles within their organizations.

Table 1. Characteristics of the respondents (n = 78) and their organizations

There were 53 statements at the individual level, 22 at the interpersonal level, 21 in community, 51 in organizational, and 25 in policy. lists examples of statements at each level of the model. Participants generated the most statements at the individual level of the SEM. For the individual level, brainstormed responses were coded into six sub-themes: misconceptions (n = 23), providers (n = 11), vaccine safety and effectiveness (n = 6), utilization and access (n = 6), distrust (n = 3), and other (n = 4). Interpersonal level statements were broken down into three sub-themes: communication between individuals (n = 11), consistent youth and provider education to improve their comfort with topic and patients/parents (n = 7), and factual messaging to parents (n = 4). At the community level, statements were sub-themed into media (n = 12), communication between groups (n = 6), and access (n = 3). The organizational level had the second-highest number of brainstormed responses from participants, at 51 statements. Based on the responses, four sub-themes were created for the organizational level: comprehensive educational and multi-organizational/multi-level approaches to vaccine recommendations (n = 18), system (n = 17), clinics (n = 11), and vaccine inventory (n = 5). Statements at the policy level of the SEM were broken into insurance (n = 8), vaccine requirements (n = 7), legislation (n = 6) and availability (n = 4). depicts these sub-themes at their corresponding level of the SEM.

Table 2. Examples of brainstormed statements organized by social ecological level

Discussion

Through this data collection, we are able to better understand the perceived influences on HPV vaccination uptake in both rural and urban areas through the generation of statements using concept mapping. We identified influences across multiple levels of the SEM which highlight potential targets for intervention. Participants most frequently identified influences at the individual and organizational levels, with many of the sub-themes identifying barriers that are consistent with previous research.Citation15,Citation22 Our model of factors affecting HPV vaccine uptake can be used by those looking to develop interventions or identify targets for programming. While our results are only reflective of participants in five specific states, our participants named factors that have been identified in previous research on vaccination.

In a survey of stakeholders in Virginia, organizational factors like cost and having a team or coordinate approach were identified as factors affecting HPV vaccination.Citation15 In our study, our participants similarly pointed to the coordination across the state between health clinics, hospitals, and health systems as well as funding opportunities available as factors affecting vaccination rates. Our results also echo many of the same factors affecting vaccination identified in an environmental scan of state-level stakeholders in South Carolina. For example, in the South Carolina study, systematic messaging about HPV vaccination, awareness among parents, of vaccine safety and efficacy, strong provider recommendation of the vaccine, and issues related to access were all cited as barriers to vaccination, Citation22 all of which were topics brainstormed by our participants.

When comparing themes across the levels of the SEM, we found that participants frequently reported lack of education and the misconceptions surrounding the HPV vaccine as factors that negatively influence HPV vaccine uptake. Both of these factors are well-established barriers to vaccination, Citation26 highlighting a consistent perceived concern about inaccurate information related to HPV and the HPV vaccine. Along with misconceptions at the individual level, misconceptions were also reported at the community level under the media sub-theme. Participants identified media as a major influence on HPV vaccination uptake. Although statements by participants in this study most commonly included the spread of misinformation and anti-vaccine groups, it’s influence may not always be negative and there is evidence that social media can have value in increasing vaccine acceptance.Citation27 Further, research on effects of messages and interventions presented across social media platforms would be valuable to better understand how this medium can help change negative views about HPV vaccination into positive ones.

Participants in this study identified educational approaches, particularly those delivered within clinical settings, as influential for HPV vaccination. The importance of the role of primary care providers in delivering HPV vaccine education was cited by participants across multiple levels (individual, interpersonal, and organizational). This finding is mirrored in the literature on the role of providers,Citation12,Citation28 but clinic-based education alone is not enough to increase vaccination.Citation29 Stakeholders also identified immunization information systems, provider reminders, and provider evaluation as influential factors to improve HPV vaccination, all of which reflect the need for leveraging multiple evidence-based interventions across levels of influence identified in the SEM to increase vaccination uptake.Citation30–33 Interventions focused on increasing strong recommendations from providers as well as improving health-care systems and immunization registry systems continue to be an ongoing necessity to improve vaccination rates.

Although participants identified a wide range of influences, not all may be feasible. When developing strategies to improve HPV vaccine uptake, it is important to take into account how much control actors have in implementing changes. It is particularly important to consider what is required within each social ecological level for change to occur, who has to be involved in those changes, and what the costs are for making a change. A study conducted with Vaccine for Children clinics in Iowa found that, even within a single clinic there are often multiple decision-makers involved in HPV vaccine programming, including clinic level staff, administrators, and external actors like insurance companies.Citation34 Therefore, to consider making a change at one level, it is likely that actors from multiple levels will have to be involved in order to sustainably link or implement one proposed change to all related systems or levels. Given that participants most heavily cited factors at the individual and organizational levels as influential, the question remains whether changes within and across these levels of influence are more accessible or adaptable to change and improvement. Changes at the interpersonal, community, and policy levels may be more difficult to conceptualize or perceived as difficult to change. As illustrated by the 2007 rejection of school HPV vaccine mandates in 2007 policy-level change can be particularly challenging because it can involve high levels of political power, political will, and public support.Citation35

Strengths and limitations

This study is strengthened by the use of an online participatory methodology to gather information from stakeholders with diverse expertise from multiple states. Statements generated by this population offer useful insight into what those working in health and youth-related organizations believe to be the most influential factors for HPV vaccine uptake. Moreover, we found concept mapping to be a useful methodology to organize ideas from a geographically diverse group of stakeholders on this topic in a relatively short amount of time and suggest a more widespread utilization of this data collection tool. However, limitations should also be considered. In the first place, our findings are based on the perceptions of stakeholders from five states, which may not be representative of the country as a whole and are likely not generalizable, particularly beyond the United States. Secondly, it is important to acknowledge that stakeholders’ roles in their organizations (e.g., administrative or programming) may have influenced their responses and led them to place an emphasis on factors with which they are most familiar or within the scope of their roles’ influence. Additionally, we did not elicit information on their length of time working for their organization or the extent to which they work closely with their communities. These could be factors that affected their responses and ability to fully capture the context of their states. Finally, due to the recruitment methods, it is also possible that some important stakeholders were not identified or did not participate in our study.

Conclusions

Findings from this study with stakeholders from five states echo results from similar studies conducted with state-level stakeholders elsewhere, Citation15,Citation22 as well as recommendations from national experts.Citation36 Additionally, our results highlight commonalities between the states suggesting that stakeholders should focus on coming together to discuss this issue and work across state lines to help colleagues. Given that factors were identified across all levels of the SEM, multi-level interventions to address modifiable factors may provide the best path forward. Stakeholders could use our model of factors affecting HPV vaccination as a starting point for areas to focus in and then consider their own position and ability to affect change. For example, state public health departments may have more ability to assist with creating consistent messaging across local health departments and other stakeholders, while an organization like the state academy of family physicians would have more of an influence on providers and clinics. With the breadth of brainstormed ideas from our participants at the multiple levels of the SEM, it is clear there is not a magic bullet solution to improving vaccination rates, but that changes at all levels of the SEM need to occur. Instead, stakeholders across the country could look to our results as a guide and reflect on how they might be applicable to their geographic context to help in their work to improve vaccination rates and reduce the burden of HPV-related cancers.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Rachel McGuy for her work in coding data.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

Authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Joura EA, Kjaer SK, Wheeler CM, Sigurdsson K, Iversen O, Hernandez-Avila M, … Barr E. HPV antibody levels and clinical efficacy following administration of a prophylactic quadrivalent HPV vaccine. Vaccine. 2008;26(52):6844–51. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.09.073.

- Meites EA, Szilagyi PG, Chesson HW, Unger ER, Romero JR, Markowitz LE. Human papillomavirus vaccination for adults: updated recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices. Morbidity Mortality Weekly Rep. 2019;68(32):698–702. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6832a3.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Immunization and infectious diseases. In Healthy People 2020; 2018. [accessed 2020 Jan 1]. Available from https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/immunization-and-infectious-diseases/objectives.

- Elam-Evans LE, Yankey D, Singleton JA, Sterrett N, Markowitz LE, Williams CL, Stokley S, McNamara L, Stokley S. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years—United States, 2019. Morbidity Mortality Weekly Rep. 2020;69(33):1109–16. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6933a1.

- Swiecki-Sikora AL, Henry KA, Kepka D. HPV vaccination coverage among US teens across the rural-urban continuum. J Rural Health. 2019;35(4):506–17. doi:10.1111/jrh.12353.

- Williams CL, Walker TY, Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, Fredua B, Saraiya M, Stokley S. Factors associated with not receiving HPV vaccine among adolescents by metropolitan statistical area status, United States, national immunization survey-teen, 2016-2017. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16(3):562–72. doi:10.1080/21645515.2019.1670036.

- Nickel B, Dodd RH, Turner RM, Waller J, Marlow L, Zimet G, Ostini R, McCaffery K. Factors associated with human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination across three countries following vaccine introduction. Preventive Med Rep. 2017;8:169–76. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2017.10.005.

- Karafillakis E, Simas C, Jarrett C, Verger P, Peretti-Watel P, Dib F, Larson H, Takacs J, Ali KA, Pastore Celentano L. HPV vaccination in a context of public mistrust and uncertainty: A systematic literature review of determinants of HPV vaccine hesitancy in Europe. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(7–8):1615–27. doi:10.1080/21645515.2018.1564436.

- Loke AY, Kwan ML, Wong Y, Wong AKY. The uptake of human papillomavirus vaccination and its associated factors: a systematic review. J Prim Care Community Health. 2017;8(4):349–62. Cox, D. S., Cox, A. D., Sturm, L., & Zimet, G. (2010). Behavioral interventions to increase HPV vaccination acceptability among mothers of young girls. Health Psychology, 29(1), 29–39. doi:10.1177/2150131917742299.

- Hopfer S. Effects of a narrative HPV vaccination intervention aimed at reaching college women: a randomized controlled trial. Prev Sci. 2011;13(2):173–82. doi:10.1007/s11121-011-0254-1.

- Krawczyk AL, Perez S, Lau E, Holcroft CA, Amsel R, Knäuper B, Rosberger Z. Human papillomavirus vaccination intentions and uptake in college women. Health Psychol. 2012;31(5):685–93. doi:10.1037/a0027012.

- Perkins RB, Zisblatt L, Legler A, Trucks E, Hanchate A, Gorin SS. Effectiveness of a provider-focused intervention to improve HPV vaccination rates in boys and girls. Vaccine. 2015;33(9):1223–29. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.11.021.

- Reiter PL, Stubbs B, Panozzo CA, Whitesell D, Brewer NT. HPV and HPV vaccine education intervention: effects on parents, healthcare staff, and school staff. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(11):2354–61. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.epi-11-0562.

- Vanderpool RC, Cohen EL, Crosby RA, Jones MG, Bates W, Casey BR, Collins T. “1-2-3 Pap” intervention improves HPV vaccine series completion among appalachian women. J Commun. 2013;63(1):95–115. doi:10.1111/jcom.12001.

- Cartmell KB, Young-Pierce J, Mcgue S, Alberg AJ, Luque JS, Zubizarreta M, Brandt HM. Barriers, facilitators, and potential strategies for increasing HPV vaccination: A statewide assessment to inform action. Papillomavirus Res. 2018;5:21–31. doi:10.1016/j.pvr.2017.11.003.

- Kane M, Trochim WM. Applied social research methods: concept mapping for planning and evaluation. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc; 2007. doi:10.4135/9781412983730.

- Burke JG, O’Campo P, Peak GL, Gielen AC, McDonnell KA, Trochim WMK. An Introduction to concept mapping as a participatory public health research method. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(10):1392–410. doi:10.1177/1049732305278876.

- Aarons GA, Wells RS, Zagursky K, Fettes DL, Palinkas LA. Implementing evidence-based practice in community mental health agencies: a multiple stakeholder analysis. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(11):2087–95. doi:10.2105/ajph.2009.161711.

- Vinson CA. Using concept mapping to develop a conceptual framework for creating virtual communities of practice to translate cancer research into practice. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014:11. doi:10.5888/pcd11.130280.

- Askelson NM, Golembiewski EH, Depriest AM, O’Neill P, Delger PJ, Scheidel CA. The answer isn’t always a poster: using social marketing principles and concept mapping with high school students to improve participation in school breakfast. Soc Mar Q. 2015;21(3):119–34. doi:10.1177/1524500415589591.

- Velonis A, Forst L. Outreach to low-wage and precarious workers: concept mapping for public health officers. J Occup Environ Med. 2018;60(11):e61–e617. doi:10.1097/JOM.0000000000001462.

- Carhart MY, Schminkey DL, Mitchell EM, Keim-Malpass J. Barriers and facilitators to improving virginias HPV vaccination rate: a stakeholder analysis with implications for pediatric nurses. J Pediatr Nurs. 2018;42:1–8. doi:10.1016/j.pedn.2018.05.008.

- Lanning B, Golman M, Crosslin K. Improving human papillomavirus vaccination uptake in college students: a socioecological perspective. Am J Health Educ. 2017;48(2):116–28. doi:10.1080/19325037.2016.1271753.

- The Concept System Global Max [Computer software]; 2019. [accessed 2020 July 1]. Available from https://conceptsystemsglobal.com

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The social ecological model: a framework for prevention; 2019. [accessed 2020 July 1]. Available from http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/overview/social-ecologicalmodel.html.

- Vamos CA, Vázquez-Otero C, Kline N, Lockhart EA, Wells KJ, Proctor S, Daley EM. Multi-level determinants to HPV vaccination among Hispanic farmworker families in Florida. Ethn Health. 2018:1–18. doi:10.1080/13557858.2018.1514454.

- Nowak GJ, Gellin BG, MacDonald NE, Butler R, On V. H SWG. Addressing vaccine hesitancy: the potential value of commercial and social marketing principles and practices. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4202–11. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.039.

- Jarrett C, Wilson R, O’Leary M, Eckersberger E, Larson HJ; SageWorking Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Strategies for addressing vaccine hesitancy - A systematic review. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4180–90. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.040.

- Community Preventive Services Task Force (CPSTF). Increasing appropriate vaccination: clinic-based client education when used alone; 2015. [accessed 2020 July 1]. Available from https://www.thecommunityguide.org/sites/default/files/assets/Vaccination-Clinic-Based-Education.pdf

- Community Preventive Services Task Force (CPSTF). Increasing appropriate vaccination: immunization information systems; 2014. [accessed 2020 July 1]. Available from https://www.thecommunityguide.org/sites/default/files/assets/Vaccination-Immunization-Info-Systems.pdf

- Community Preventive Services Task Force (CPSTF). Increasing appropriate vaccination: provider reminders; 2016a. [accessed 2020 July 1]. Available from https://www.thecommunityguide.org/sites/default/files/assets/Vaccination-Provider-Reminders.pdf

- Community Preventive Services Task Force (CPSTF). Increasing appropriate vaccination: provider assessment and feedback; 2016b. [accessed 2020 July 1]. Available from https://www.thecommunityguide.org/sites/default/files/assets/Vaccination-Provider-Assessment-and-Feedback.pdf

- Smulian EA, Mitchell KR, Stokley S. Interventions to increase HPV vaccination coverage: A systematic review. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12(6):1566–88. doi:10.1080/21645515.2015.1125055.

- Askelson NM, Ryan G, Seegmiller L, Pieper F, Kintigh B, Callaghan D. Implementation challenges and opportunities related to HPV vaccination quality improvement in primary care clinics in a rural state. J Community Health. 2019;44(4):790–95. doi:10.1007/s10900-019-00676-z.

- Haber G, Malow RM, Zimet GD. The HPV vaccine mandate controversy. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2007;20(6):325–31. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2007.03.101.

- Reiter PL, Gerend MA, Gilkey MB, Perkins RB, Saslow D, Stokley S, Brewer NT, Zimet GD, Brewer NT. Advancing human papillomavirus vaccine delivery: 12 priority research gaps. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(2 Supply):S14–S16. doi:10.1016/j.acap.2017.04.03.