ABSTRACT

Background: Vaccine hesitancy has been recognized as an urgent public health issue. We aimed to explore the acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine and related factors among pregnant women, a vulnerable population for vaccine-preventable diseases.

Methods: A multi-center cross-sectional study among pregnant women was conducted in five provinces of mainland China from November 13 to 27, 2020. We collected sociodemographic characteristics, attitude, knowledge, and health beliefs on COVID-19 vaccination. Locally weighted scatterplot smoothing regression analysis was used to assess the trends of vaccination acceptance. Multivariable logistic regression was performed to identify factors related to vaccination acceptance.

Results: Among the 1392 pregnant women, the acceptance rate of a COVID-19 vaccine were 77.4% (95%CI 75.1–79.5%). In the multivariable regression model, the acceptance rate was associated with young age (aOR = 1.87, 95% CI: 1.20–2.93), western region (aOR = 2.73, 95% CI: 1.72–4.32), low level of education (aOR = 2.49, 95% CI: 1.13–5.51), late pregnancy (aOR = 1.49, 95% CI: 1.03–2.16), high knowledge score on COVID-19 (aOR = 1.05, 95% CI: 1.01–1.10), high level of perceived susceptibility (aOR = 2.18, 95% CI: 1.36–3.49), low level of perceived barriers (aOR = 4.76, 95% CI: 2.23–10.18), high level of perceived benefit (aOR = 2.18, 95% CI: 1.36–3.49), and high level of perceived cues to action (aOR = 15.70, 95% CI: 8.28–29.80).

Conclusions: About one quarters of pregnant women have vaccine hesitancy. Our findings highlight that targeted and multipronged efforts are needed to build vaccine literacy and confidence to increase the acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially for vulnerable populations.

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a new acute respiratory infectious disease that has become a major global public health event. As of November 22, 2020, there have been over 100 million confirmed cases and over 2 million deaths reported globally since the start of the COVID-19 pandemicCitation1. Scientists are nervously looking for effective treatments and preventions against the COVID-19. In the protection of susceptible people, vaccination is the most effective way to prevent infectious diseases, and enough vaccination can produce effective herd immunity.Citation2–4 At present, there is an urgent need to develop, produce and vaccinate safe and effective vaccines on a global scale, and various scientific institutions are also making full efforts in this regard. Advances in virology, molecular biology, and immunology have also brought new breakthroughs in vaccine development, resulting in nucleic acid-based (mRNA, DNA) vaccines, viral vectored vaccines, and subunit vaccines. COVID-19 has brought all vaccine types to the forefront of the fight against the pandemic. The landscape documents provided by WHO show that a total of 48 vaccine candidates are currently in the clinical evaluation stage, and 164 candidate vaccines are in the preclinical evaluation stage.Citation5

Despite remarkable advances in vaccine research and development, vaccine hesitancy has been recognized as a public health threat.Citation6 Vaccine hesitancy, reflecting concerns about the decision to vaccinate oneself or one’s children, is believed to be responsible for decreasing vaccine coverage and an increasing risk of outbreaks for vaccine-preventable disease.Citation7 Some studies reported that the acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine in the general population varied in different countries, 90% in China,Citation8 70% in the United States,Citation9,Citation10 75% in France.Citation11,Citation12 A global survey reported that 28.5% of the participants would be unlikely or not sure to take a COVID-19 vaccine, ranged from 10% to 45%.Citation13 Previous studies had shown that a broad range of factors contributed to vaccine hesitancy, including the compulsory nature of vaccines, their coincidental temporal relationships to adverse health outcomes, unfamiliarity with vaccine-preventable diseases, and lack of trust.Citation7 Lazarus and colleagues found that lower levels of trust in information for government sources were associated with less likely to accept a COVID-19 vaccine in a cross-sectional study conducted in 19 countries.Citation13

Studies have shown a decline in the willingness to vaccinate over the past decade, along with the increasingly vocal anti-vaccination lobby around the world.Citation14,Citation15 It is important to understand the population’s vaccination barriers, which will help us to carry out the popularization of COVID-19 vaccines more effectively, especially among vulnerable population (e.g., pregnant women). Pregnant women usually have lower willingness and more concerns about vaccination for vaccine-preventable disease (i.e., influenza) than the general population.Citation16,Citation17 Maternal immunizations contribute to the protection of infants from serious diseases during the early period of life.Citation18 In China, pregnant women have been listed as the priority population to receive influenza vaccines at any gestational age to prevent them from adverse pregnancy outcomes and protect their infants from influenza since 2014.Citation19 Although as the population recommended for vaccination in priority, pregnant women are often unwilling to receive influenza vaccination because of their lack of relevant knowledge, negative attitudes toward vaccines, no experience in influenza vaccination, and worry about the occurrence of adverse events and uncertain vaccine safety.Citation20,Citation21 Individually tailored messages for pregnant women who have vaccine concerns are helpful to avoid vaccine refusal.Citation22 However, literature on the acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine and related factors among pregnant women was scarce. According to the report on prioritizing uses of COVID-19 vaccines in the context of limited supply by the WHO, pregnant women warrant particular consideration, as this group has been disadvantaged with respect to the development and deployment of vaccines in previous pandemics.Citation23 Understanding the willingness of COVID-19 and causes of vaccine hesitancy pregnant women is crucial to make tailored preparation to address hesitancy and built vaccine literacy. In the present study, we conducted a hospital-based multi-center cross-sectional study among pregnant women in mainland China to explore the acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine and factors related to vaccine acceptance based on the health belief model, a commonly used theory model on vaccine hesitancy.Citation24

Methods

Study design and participants

This was a multi-center hospital-based cross-sectional study among pregnant women in mainland China. We adopted a multistage sampling approach to select participants. In the first stage, we divided mainland China into three (eastern, central and western) regions, according to the National Bureau of Statistics of China. Five provinces were randomly selected, namely Beijing (eastern), Hebei (eastern), Hubei (central), Anhui (central), and Yunnan (western), which, respectively, represent eastern, central, and western region in China. In the second stage, we selected a convenience sample of six hospitals from different regions of China, namely Tongzhou Maternal and Child Health Hospital (Beijing), Qianjiang Maternal and Child Health Hospital (Hubei), Shexian Maternal and Child Health Hospital (Hebei), Mingguang Maternal and Child Health Hospital (Anhui), the Second Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University (Yunnan), Qujing Maternal and Child Health Hospital (Yunnan). In the third stage, all pregnant women who received antenatal care in obstetric clinics of 6 hospitals from November 13 to 27, 2020 were recruited. Inclusion criteria were 1) women aged 18 years or above; 2) pregnant women who attended antenatal clinics in the participating obstetric hospitals during 13 November 2020 to 27 November 2020; 3) voluntary agreement to participant in the present study. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Peking University Third Hospital and conducted according to the Helsinki Declaration. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Data collection

Based on a review of the literature on the acceptance of vaccination on respiratory infectious disease (e.g., influenza) in pregnant women,Citation20,Citation24,Citation25 we developed a structured questionnaire to collect data on sociodemographic characteristics, health status, knowledge on COVID-19 infection, attitude toward COVID-19 vaccination, and health beliefs related with COVID-19 infection and vaccination.

Sociodemographic characteristics included age group, region, education, occupation, monthly household income per capita. Health status included gravidity, parity, gestational trimester, history of adverse pregnancy outcomes, history of chronic disease, history of influenza vaccination, and gestational complications.

History of adverse pregnancy outcomes of pregnant women was collected by asking the question ‘Do you have the history of any adverse pregnancy outcomes, such as miscarriage, low birth weight, stillbirth, preterm birth, or macrosomia? (yes or no)’. We used the question ‘have you been diagnosed as having any chronic disease, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension, respiratory diseases, or cancer? (yes or no)’ to collect the history of chronic disease. Gestational complications refer to currently having been diagnosed as gestational diabetes mellitus, gestational hypertension, gestational thyroid disorder, gestational anemia in this study.

In the present study, knowledge toward COVID-19 infection consisted of 17 items, including source of infection, route of transmission, susceptible population, common symptoms, high-risk population for severe illness and death, individual preventive measures for COVID-19 infection. There were three possible responses (yes, no, or not sure). For each item, if correct answer was chosen, the respondent received 1 score. Wrong answer or responses “unknow” received zero score. The sum of the score for all the 17 items was calculated as the total knowledge score on COVID-19, which ranged from 0 to 17. The higher the score, the more knowledge participants got. The total knowledge score was divided into three groups (low, moderate, high) by tertiles.

Attitude toward COVID-19 vaccination

The primary outcome is the acceptance of a potential COVID-19 vaccine. The acceptance of a potential COVID-19 vaccine was collected by the question “If a vaccine for the COVID-19 infection becomes available, will you get vaccinated during pregnancy? (yes, no or not sure)”. Pregnant women who responded “no or not sure” were then asked the reasons for vaccine hesitation by the question “What makes you unwilling (or unsure) to get the vaccine?”. Acceptable price for the COVID-19 vaccine was also collected among all participants by the question “How much do you think the price of the COVID-19 vaccine is acceptable? (cost of whole stage of vaccination)” followed by the response options “only acceptable for free”, “<200 RMB”, “201–400 RMB”, ”401–600 RMB”, and “>600 RMB”.

Health beliefs related with COVID-19 infection and vaccination

To further assess the factors related to the attitude toward COVID-19 vaccine, we developed several questions based on the health belief model.Citation24,Citation26 We adapted and modified questions from the previous published literature on other vaccine-preventable disease.Citation24,Citation26 All participants responded to the questions. The health belief model included five dimensions that might influence individuals’ health behaviors, namely perceptions of susceptibility, severity, barriers, benefits and cues to action. It is assumed in the health belief model that individuals are more likely to take behaviors to prevent disease (such as vaccination) if they perceive that they are susceptible to the disease, the disease is severe, the behavior is beneficial, or the barriers are minimal.Citation26,Citation27 The recommendation from doctors on vaccination or health education messages can also influence the vaccination behaviors, which is cues to action.Citation28 In the present study, there were totally 12 items focused on factors related to the attitude toward COVID-19 vaccine, including perceived susceptibility to COVID-19 infection for mother and infant (2 items), perceived severity of COVID-19 infection for mother and infant (2 items), perceived barriers of COVID-19 vaccination (3 items), benefits of COVID-19 vaccination (3 items) and cues to action (2 items). The response answers of “very concerned or agree”, “moderate concerned or not sure”, “not concerned or disagree” was recorded as 3, 2, and 1 score, respectively. The summed scores for each dimension of the health belief model framework were calculated accordingly. The participants were divided into three groups (low, moderate, high) by tertiles according to the summed score for each HBM dimension. A pilot testing was conducted among a convenience sample of 20 pregnant women and the Cronbach’s α coefficient of the health belief model constructs was 0.81 for perceived susceptibility, 0.88 for perceived severity, 0.76 for perceived barriers, 0.87 for perceived benefits, and 0.95 for cues to action, respectively, showing a good internal consistency reliability.

Data analysis

Characteristics of all the recruited pregnant women were summarized by using frequencies and percentages. The total proportion of the acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine and its 95% CI was calculated, as well as the proportions of the acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine by different characteristics. We used Pearson’s χ2 test to compared the acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine by sociodemographic characteristics, health status, knowledge factors, and health beliefs. Cochran-Armitage test for trend was used for examining the trend of proportion of the acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine by characteristics.

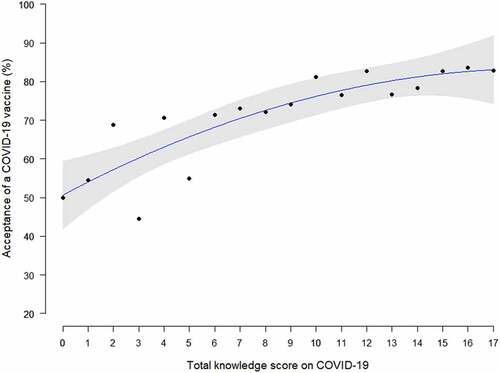

To assess the adjusted associations of factors related to the acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine, we used multivariable logistic regression model. We adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics (age group, region, education, occupation, monthly household income per capita), health status (gravidity, parity, gestational trimester, history of adverse pregnancy outcomes, history of chronic disease, history of influenza vaccination, and gestational complications), total knowledge score on COVID-19 (as continuous variable), health belief (susceptibility, severity, barriers, benefits, and cues to action). Adjusted odds ratios with 95%CIs for each variable were calculated. We used locally weighted scatterplot smoothing regression analysis to assess the trends in the acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine and the total knowledge score on COVID-19. All the data analyses were conducted by using R (version 3.6.3) and SAS (version 9.4).

Results

Characteristics of the study population

A total of 1392 pregnant women were included in this study (). 55.4% of them were 30 years old or below, and 35.9% had a bachelor’s degree or above. 38.6% were first pregnant women, 32.0% women had a history of adverse pregnancy outcomes, and 2.3% women had a history of chronic disease. Only 8.8% of all participants had history of influenza vaccination. There were 23.5% women diagnosed with gestational complications in the current pregnancy.

Table 1. Acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine of pregnant women in China by sociodemographic characteristics, health status and knowledge factors

Acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine of pregnant women by sociodemographic characteristics, health status, and knowledge factors

The proportion of acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine were 77.4% (95%CI 75.1–79.5%) among all participants. The acceptance rates decreased significantly along with the increasing age (p trend<0.05), from 81.7% in women aged 25 years or below to 66.7% in women aged above 40 years. Pregnant women with younger age, lower education, living in western region, second and third gestational trimester, with gestational complications, and higher knowledge score on COVID-19 infection were more likely to accept COVID-19 vaccination (all p < .05, ). The acceptance rates of a COVID-19 vaccine were significantly increased with the increasing total knowledge score on COVID-19 infection by locally weighted scatterplot smoothing regression analysis (p < .01, ). Nearly one quarter (24.4%) of all participants only accept the COVID-19 vaccination for free. There were totally 80.4% of pregnant women who responded that the acceptable price of the COVID-19 vaccine (cost for the whole stage of vaccination) was <200 RMB.

Comparison of the acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine by health beliefs

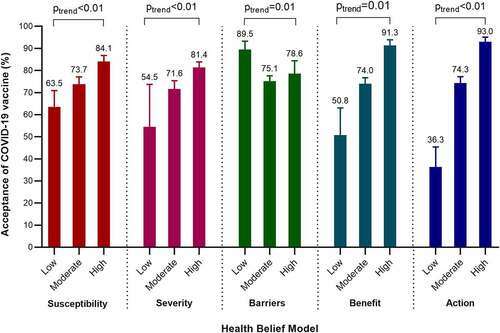

Pregnant women who were concerned about getting COVID-19 were more likely to accept COVID-19 vaccination (79.0%) than those not concerned (63.5%, p < .01, ). Pregnant women who agreed with the benefit of vaccination to her fetus and baby had higher level of acceptance (78.7%) than those not agreed (57.0%, p < .01). Pregnant women perceived cues to action (receiving vaccine recommendation from doctors) were more likely to accept COVID-19 vaccine (80.6%) than those not perceived (33.3%, p < .01). The acceptance rates of a COVID-19 vaccine were significantly higher in pregnant women with high level of perceived susceptibility to COVID-19 infection, severity of COVID-19 infection, benefits of COVID-19 vaccination, and cues to action than those with low level (all p trend<0.05), while it was significantly lower in pregnant women with higher level of perceived barriers of vaccination (50.8% vs 91.3%, ).

Table 2. Comparison of the acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine by health beliefs (n = 1392)

Factors associated with the acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine

In the multivariable regression model (), the acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine was associated with young age (aOR = 1.87, 95% CI: 1.20–2.93), western region (aOR = 2.73, 95% CI: 1.72–4.32), low level of education (aOR = 2.49, 95% CI: 1.13–5.51), late pregnancy (aOR = 1.49, 95% CI: 1.03–2.16), high knowledge score on COVID-19 (aOR = 1.05, 95% CI: 1.01–1.10), high level of perceived susceptibility (aOR = 2.18, 95% CI: 1.36–3.49), low level of perceived barriers (aOR = 4.76, 95% CI: 2.23–10.18), high level of perceived benefit (aOR = 2.18, 95% CI: 1.36–3.49), and high level of perceived cues to action (aOR = 15.70, 95% CI: 8.28–29.80).

Table 3. Factors associated with the acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine (n = 1392)

Reasons for responding not intend to be vaccinated with a COVID-19 vaccine

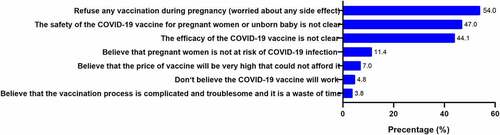

Among the 315 (22.6%, 95% CI: 20.5%-24.9%) pregnant women with vaccine hesitancy, 54% of them refuse any vaccination during pregnancy due to their worry on any side effect. 47.0% of them concerned about the safety and 44.1% concerned about the efficacy of the COVID-19 vaccine on pregnant women and unborn baby ().

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine and associated factors among pregnant women. In this multi-center hospital-based cross-sectional study, we found that acceptance rate of a COVID-19 vaccine was 77.4% (95%CI 75.1–79.5%) among pregnant women in mainland China. Our findings were much lower than the results in the general population in China (almost 90%) in previous study.Citation8,Citation13 However, the willingness of vaccination was higher than that of the general population in other countries, such as the United States (75.42%), Italy (70.79%), Canada (68.74%), Germany (68.42), Russia (54.85%).Citation13 Another cross-sectional study found that only 57.6% of adults living in the United States were willing to be vaccinated for COVID-19 when the vaccine was available.Citation9 At the same time, our results were more consistent with the results of the survey in France in March this year in the general population. The study showed that 74% of participates would be willing to receive the COVID-19 vaccine among the general population in France.Citation12

A lower acceptance was also observed in other vaccine-preventable diseases among pregnant women than the general population, such as seasonal influenza. Pregnant women are among the recommended vaccinated population of the seasonal influenza vaccine with priority by the WHO as they are the important risk group for infection,Citation29 and studies has been shown that both pregnant women and infants would benefit from the vaccination.Citation30,Citation31 However, previous surveys showed that the acceptance of the seasonal influenza vaccine was low among pregnant women, which was 70.5% in the United States,Citation32 27.9% in Italy,Citation33 47.5% in the United Kingdom,Citation34 and 76.28% in China.Citation24 Meanwhile, the uptake of seasonal influenza vaccines among adults around the world was relatively low, which was 41% in the United States in 2016,Citation35 43.6% in Korea during 2011/12 season,Citation36 42.1% among adults with chronic conditions in Italy during 2017/18 seasonCitation37 and 15.2% among adults aged above 50 in Singapore in 2016.Citation38 The acceptance rate of COVID-19 vaccination in this study was close to the influenza vaccination rate among Chinese pregnant women in previous studies (both are close to 75%), which meant that about a quarter of pregnant women have vaccine hesitation. Our findings highlighted that vaccine hesitation is still worthy to be noticed, when the COVID-19 vaccine was available for the public.

Our study showed that younger pregnant women were more likely to accept COVID-19 vaccination. The willingness of vaccination among pregnant women ≤25 years old was 81.7%, and women over 40 years old was 66.7%. This suggested that the younger pregnant woman, the more focused on the covid-19 vaccine’s protective effect. When it comes to influenza vaccination, previous studies had also shown that younger people were more likely to be vaccinated in the pregnant women.Citation17,Citation25 But in the general population, this result was the opposite. Older people seemed to be more willing to receive the COVID-19 vaccine than younger people.Citation9,Citation11,Citation13 This finding might reflect the fact that the pregnant women with advanced maternal age are more worried about the side effects of the vaccine on pregnancy, while the older people in the general population are more worried about the risk of disease. Our results also suggested that pregnant women in western China and low education level have higher COVID-19 vaccination intentions. The pregnant women with higher education level had higher vaccine hesitation in China, which was related to their knowledge of COVID-19 vaccine, and they might get more negative information about the COVID-19 vaccine. Therefore, this suggested that we should strengthen the timely disclosure and transparency of vaccine researchCitation8 and development and monitoring information, and conduct health education by professional health care personnel, to reduce public concerned about vaccine safety.Citation39,Citation40 In terms of the choice of vaccination period, pregnant women in the second and third trimesters had higher willingness to receive the COVID-19 vaccination than those in the first trimester (82.7% vs 66.4%, 80.2% vs 66.4%). The situation was similar to the study of influenza vaccination willingness among pregnant women in Southeast Asia.Citation16,Citation20,Citation25

In this study, we set some questions to test the knowledge level of pregnant respondents, such as source of infection, route of transmission, susceptible population, and common symptoms et al. It was gratifying to note that our study found a positive correlation between total knowledge score in COVID-19 and willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccines. In the general population, many studies had also shown that higher levels of education lead to greater acceptance of COVID-19 vaccines.Citation10,Citation13 Higher levels of education tend to be associated with higher scores in knowledge. However, our previous results have shown that high levels of education among pregnant women are contrary to COVID-19 vaccination intentions. This also suggests that in the vaccination publicity of COVID-19 vaccine, we should strengthen the dissemination of correct information, so as to avoid giving wrong or worrying information to people with high education level in the early stage of vaccine development.

Pregnant women are one of the vulnerable populations. Evidence is emerging that pregnant women are at elevated risk of serious disease, further increased if they have preexisting comorbidities, and may be at elevated risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes as well.Citation23,Citation41,Citation42 Previous studies showed that COVID-19 infection was associated with higher rate of preterm birth, preeclampsia, cesarean, and perinatal death among pregnant women.Citation43 In the present study, health belief model theory provided a good framework for assessing the attitude toward COVID-19 vaccination among pregnant women. We found that perceived susceptibility, benefit, and cues to action was positively associated with willingness of vaccination, while perceived barriers were negatively associated with willingness of vaccination. Our findings were consistent with the results in other vaccine-preventable diseases in previous studies.Citation24,Citation44 There are relatively little data about the safety and efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines in pregnant women. Studies specific to pregnancy needs to be done, for example, pregnancy-specific safety and bridging studies and from participants who inadvertently become pregnant during phase III trials in the future.Citation23 More evidence on pregnant women ‘s willingness of vaccination and related factors of vaccine hesitation is also needed in other countries.

Currently, there are two licensed COVID-19 inactivated vaccines with market approval in China. According to Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, the number of COVID-19 vaccination has exceeded 24 million doses in China up to January 31, 2021.Citation45 Adults aging from 18 to 59, especially those who have higher risks of coronavirus exposure due to their occupations, are recommended to be vaccinated with COVID-19 vaccines.Citation46 Due to possible perceived risks of vaccination in pregnant women and potential exposure of their fetus to medication, a large proportion of COVID-19 vaccine clinical trials specifically excluded pregnant women.Citation47 However, the exclusion of pregnant women from COVID-19 vaccine clinical trials may result in missed opportunities to identify effective and safe prevention and treatments to prevent infection and adverse pregnancy outcomes.Citation47 Currently, pregnant women are not in the priority population to be vaccinated. Post marketing research of COVID-19 vaccines on risk-benefit assessment among vulnerable populations (e.g., pregnant women and old population) based on real-world study is warranted in the future.Citation48

There were several limitations in this study. First, hospitals were not randomly selected at the second stage. Nevertheless, it was a multicenter study conducted in six hospitals from eastern, central, and western regions to better reflect the vaccination intention of pregnant women in China. Second, pregnant women who never took antenatal examination were not included in this study. Third, this study was conducted only in China. The findings should be explained with caution when extrapolating to other countries. Studies are needed to conducted among pregnant women in other countries in the future.

In conclusion, 77.4% of pregnant women are willing to be vaccinated during when a COVID-19 vaccine is available in mainland China. The acceptance rate was associated with young age, western region, low level of education, late pregnancy, high knowledge score on COVID-19, high level of perceived susceptibility, low level of perceived barriers, high level of perceived benefit, and high level of perceived cues to action. These findings suggest that targeted and multipronged efforts are needed to build vaccine literacy and confidence to increase the acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine, especially for vulnerable populations.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Author contributions

Jue Liu contributed to conception, design, data acquisition and interpretation, and revised the manuscript. Liyuan Tao contributed to design, data acquisition and interpretation, performed all statistical analyses, drafted and revised the manuscript. Ruitong Wang contributed to conception, design, data acquisition, and revised the manuscript. Na Han, Jihong Liu, Chuanxiang Yuan, Lixia Deng, Chunhua Han, Fenglan Sun contributed to data collection and revised the manuscript. Min Liu contributed to revised the manuscript. All authors gave final approval and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Key Research and Development Project of China (2020YFC0846300; 2019YFC1710301), the National Science and Technology Key Projects on Prevention and Treatment of Major infectious disease of China (2020ZX10001002) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (71874003 and 81703240). We thank all the health workers in the department of obstetrics clinic unit of the six hospitals for their great efforts made on data collection.

Additional information

Funding

References

- World Health Organization. COVID-19 weekly epidemiological update. Data as received by WHO from national authorities, as of 22 November 2020, 10 am CET. 2020 [accessed 2014 Jan 20] https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update—24-november-2020

- Anderson RM, Vegvari C, Truscott J, Collyer BS. Challenges in creating herd immunity to SARS-CoV-2 infection by mass vaccination. Lancet. 2020;396:1614–16.

- Brisson M, É B, Drolet M, Bogaards JA, Baussano I, Vänskä S, Jit M, Boily M, Smith MA, Berkhof J, et al. Population-level impact, herd immunity, and elimination after human papillomavirus vaccination: a systematic review and meta-analysis of predictions from transmission-dynamic models. Lancet Public Health. 2016;1(1):e8–e17.

- Iwasaki A, Omer SB. Why and how vaccines work. Cell. 2020;183:290–95.

- World Health Organization. Draft landscape of COVID-19 candidate vaccines, 12 November 2020 [accessed 2014 Jan 20]. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/draft-landscape-of-covid-19-candidate-vaccines.

- McAteer J, Yildirim I, The CA. VACCINES act: deciphering vaccine hesitancy in the time of COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:703–05.

- Salmon DA, Dudley MZ, Glanz JM, Omer SB. Vaccine hesitancy: causes, consequences, and a call to action. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49:S391–S398.

- Wang J, Jing R, Lai X, Zhang H, Lyu Y, Knoll MD, Fang H. Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Vaccines. 2020;8:482.

- Fisher KA, Bloomstone SJ, Walder J, Crawford S, Fouayzi H, Mazor KM. Attitudes toward a potential SARS-CoV-2 vaccine: a survey of U.S. Adults. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:964–73.

- Pogue K, Jensen JL, Stancil CK, Ferguson DG, Hughes SJ, Mello EJ, Burgess R, Berges BK, Quaye A, Poole BD. Influences on attitudes regarding potential COVID-19 vaccination in the United States. Vaccines. 2020;8(4):582. doi:10.3390/vaccines8040582.

- Detoc M, Bruel S, Frappe P, Tardy B, Botelho-Nevers E, Gagneux-Brunon A. Intention to participate in a COVID-19 vaccine clinical trial and to get vaccinated against COVID-19 in France during the pandemic. Vaccine. 2020;38:7002–06.

- Peretti-Watel P, Seror V, Cortaredona S, Launay O, Raude J, Verger P, Fressard L, Beck F, Legleye S, L’Haridon O, et al. A future vaccination campaign against COVID-19 at risk of vaccine hesitancy and politicisation. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(7):769–70.

- Lazarus JV, Ratzan SC, Palayew A, Gostin LO, Larson HJ, Rabin K, Kimball S, El-Mohandes A. A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nat Med. 2021;27(2):225–228.

- Shetty P. Experts concerned about vaccination backlash. Lancet. 2010;375:970–71.

- Larson HJ, De Figueiredo A, Xiahong Z, Schulz WS, Verger P, Johnston IG, Cook AR, Jones NS. The state of vaccine confidence 2016: global insights through a 67-country survey. EBioMedicine. 2016;12:295–301.

- Offeddu V, Tam CC, Yong TT, Tan LK, Thoon KC, Lee N, Tan TC, Yeo GSH, Yung CF. Coverage and determinants of influenza vaccine among pregnant women: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:890.

- Wang J, Sun D, Abudusaimaiti X, Vermund SH, Li D, Hu Y. Low awareness of influenza vaccination among pregnant women and their obstetricians: a population-based survey in Beijing, China. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15:2637–43.

- Blanchard-Rohner G, Eberhardt C. Review of maternal immunisation during pregnancy: focus on pertussis and influenza. Swiss Med Wkly. 2017;147:w14526.

- Feng L, Yang P, Zhang T, Yang J, Fu C, Qin Y, Zhang Y, Ma C, Liu Z, Wang Q, et al. Technical guidelines for the application of seasonal influenza vaccine in China (2014-2015). Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2015;11(8):2077–101.

- Chang YW, Tsai SM, Lin PC, Chou FH. Willingness to receive influenza vaccination during pregnancy and associated factors among pregnant women in Taiwan. Public Health Nurs. 2019;36:284–95.

- Otieno NA, Nyawanda B, Otiato F, Adero M, Wairimu WN, Atito R, Wilson AD, Gonzalez-Casanova I, Malik FA, Verani JR, et al. Knowledge and attitudes towards influenza and influenza vaccination among pregnant women in Kenya. Vaccine. 2020;38(43):6832–38.

- Salmon DA, Dudley MZ, Glanz JM, Omer SB. Vaccine hesitancy: causes, consequences, and a call to action. Vaccine. 2015;33:D66–D71.

- World Health Organization. WHO sage roadmap for prioritizing uses of COVID-19 vaccines in the context of limited supply. Avaliable online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/covid-19-vaccines (acessed on 3 Dec 2020).

- Hu Y, Wang Y, Liang H, Chen Y. Seasonal influenza vaccine acceptance among pregnant women in Zhejiang Province, China: evidence based on health belief model. Int J Env Res Public Health. 2017;14:1551.

- Ditsungnoen D, Greenbaum A, Praphasiri P, Dawood FS, Thompson MG, Yoocharoen P, Lindblade KA, Olsen SJ, Muangchana C. Knowledge, attitudes and beliefs related to seasonal influenza vaccine among pregnant women in Thailand. Vaccine. 2016;34:2141–46.

- Rosenstock IM, Strecher VJ, Becker MH. Social learning theory and the health belief model. Health Educ Q. 1988;15:175–83.

- Chen MF, Wang RH, Schneider JK, Tsai CT, Jiang DD, Hung MN, Lin LJ. Using the health belief model to understand caregiver factors influencing childhood influenza vaccinations. J Community Health Nurs. 2011;28:29–40.

- Smith PJ, Humiston SG, Marcuse EK, Zhao Z, Dorell CG, Howes C, Hibbs B. Parental delay or refusal of vaccine doses, childhood vaccination coverage at 24 months of age, and the health belief model. Public Health Rep. 2011;126:135–46.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Flu & pregnant women [accessed 2014 Jan 20]. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/highrisk/pregnant.htm.

- Thompson MG, Kwong JC, Regan AK, Katz MA, Drews SJ, Azziz-Baumgartner E, Klein NP, Chung H, Effler PV, Feldman BS, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in preventing influenza-associated hospitalizations during pregnancy: a multi-country retrospective test negative design study, 2010–2016. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68(9):1444–53.

- Mohammed H, Roberts CT, Grzeskowiak LE, Giles LC, Dekker GA, Marshall HS. Safety and protective effects of maternal influenza vaccination on pregnancy and birth outcomes: a prospective cohort study. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;26:100522.

- Ding H, Black CL, Ball S, Fink RV, Williams WW, Fiebelkorn AP, Lu PJ, Kahn KE, D’Angelo DV, Devlin R, et al. Influenza vaccination coverage among pregnant women - United States, 2016-17 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(38):1016–22.

- D’Alessandro A, Napolitano F, D’Ambrosio A, Angelillo IF. Vaccination knowledge and acceptability among pregnant women in Italy. Hum Vacc Immunother. 2018;14:1573–79.

- Donaldson B, Jain P, Holder BS, Lindsey B, Regan L, Kampmann B. What determines uptake of pertussis vaccine in pregnancy? A cross sectional survey in an ethnically diverse population of pregnant women in London. Vaccine. 2015;33:5822–28.

- Ahmed N, Quinn SC, Hancock GR, Freimuth VS, Jamison A. Social media use and influenza vaccine uptake among White and African American adults. Vaccine. 2018;36:7556–61.

- Yang HJ, Cho SI. Influenza vaccination coverage among adults in Korea: 2008-2009 to 2011-2012 seasons. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11:12162–73.

- Bertoldo G, Pesce A, Pepe A, Pelullo CP, Di Giuseppe G; Collaborative Working Group. Seasonal influenza: knowledge, attitude and vaccine uptake among adults with chronic conditions in Italy. PLoS One. 2019;14(5):e0215978.

- Ang LW, Cutter J, James L, Goh KT. Factors associated with influenza vaccine uptake in older adults living in the community in Singapore. Epidemiol Infect. 2017;145:775–86.

- Dubé E, MacDonald NE. Vaccine acceptance: barriers, perceived risks, benefits, and irrational beliefs: Bloom BR, Lambert P editors. The vaccine book. Vol. Chapter 26. 2nd. Cambridge (MA, USA): Academic Press; 2016. p. 507–08.

- Larson HJ, Jarrett C, Eckersberger E, Smith DMD, Paterson P. Understanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccination from a global perspective: a systematic review of published literature, 2007–2012. Vaccine. 2014;32:2150–59.

- Delahoy MJ, Whitaker M, O’Halloran A, Chai SJ, Kirley PD, Alden N, Kawasaki B, Meek J, Yousey-Hindes K, Anderson EJ, et al. Characteristics and maternal and birth outcomes of hospitalized pregnant women with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 - COVID-NET, 13 states, March 1-August 22, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(38):1347–54.

- Allotey J, Stallings E, Bonet M, Yap M, Chatterjee S, Kew T, Debenham L, Llavall AC, Dixit A, Zhou D, et al. Clinical manifestations, risk factors, and maternal and perinatal outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnancy: living systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;370:m3320.

- Di Mascio D, Khalil A, Saccone G, Rizzo G, Buca D, Liberati M, Vecchiet J, Nappi L, Scambia G, Berghella V, et al. Outcome of coronavirus spectrum infections (SARS, MERS, COVID-19) during pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2020;2:100107.

- Chen MF, Wang RH, Schneider JK, Tsai CT, Jiang DD, Hung MN, Lin LJ. Using the health belief model to understand caregiver factors influencing childhood influenza vaccinations. J Community Health Nurs. 2011;28:29–40.

- National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Joint prevention and control mechanism of the state council press conference on 31 January, 2021 [accessed 2014 Jan 20]. Available from: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/yqfkdt/202101/fde67feab1054b1893fdd5a841541edb.shtml

- Liang WN, Yao JH, Wu J, Liu X, Liu J, Zhou L, Chen C, Wang GF, Wu ZY, Yang WZ, et al. [Experience and thinking on the normalization stage of prevention and control of COVID-19 in China]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2021;101:E001. Chinese. doi:10.3760/cma.j.cn112137-20210104-00008.

- Taylor MM, Kobeissi L, Kim C, Amin A, Thorson AE, Bellare NB, Brizuela V, Bonet M, Kara E, Thwin SS, et al. Inclusion of pregnant women in COVID-19 treatment trials: a review and global call to action. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;S2214-109X(20):30484–88.

- Beigi RH, Krubiner C, Jamieson DJ, Lyerly AD, Hughes B, Riley L, Faden R, Karron R. The need for inclusion of pregnant women in COVID-19 vaccine trials. Vaccine. 2021;39:868–70.