ABSTRACT

Aim: We aimed to investigate factors affecting the willingness and acceptance of the SARS-CoV-2 vaccination among adults in China and sources of knowledge about the vaccine.

Methods: A cross-sectional, web-based survey was conducted from September 8th to 15th, 2020, comprising of 23 questions. Binary logistic regression analysis was performed to examine factors associated with vaccination willingness and acceptance.

Results: A total of 983 questionnaires were included and 81.3% of the participants were willing to receive the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. With a “bachelor degree or above” (OR = 0.56, p = 0.020) and believing that the vaccine would not cause SARS-CoV-2 infection (OR = 0.50, p = 0.003) were associated with an increased willingness. Aged :30 years (OR = 0.38, p = 0.001), and believing that the vaccine would not cause SARS-CoV-2 infection (OR = 0.52, p = 0.004) were associated with higher acceptance; while from Henan province (OR = 2.49, p < 0.001), not willing to vaccinate (OR = 3.86, p < 0.001), not suffering from chronic diseases (OR = 2.25, p = 0.013), and thinking it was not safe and effective in preventing COVID-19 (OR = 1.94, p = 0.001) were correlated with a lower acceptance.

Conclusions: In conclusion, age, education, and vaccine perception might be key factors affecting the vaccine willingness and acceptance. Triggering positive perception of vaccine, especially by targeting those aged <30 years, or those with below bachelor degree, or without chronic diseases might be key approaches for improving the willingness and acceptance of vaccine in China.

Introduction

At the end of 2019, there was an outbreak of pneumonia called coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19), which was firstly reported in Wuhan, Hubei, China. The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses finally named the virus to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).Citation1 A large-scale case study published by center disease control (CDC) in the United States on April 7, 2012 estimated that the Basic Reproduction Number (R0) of COVID-19 reached 5.7, which is much higher than that of SARS-CoV (R0:0.85–3).Citation2 So far, the epidemic has entered the global pandemic stage. Globally, as of February 4, 2021, the World Health Organization (WHO) has reported 103,631,793 confirmed cases of COVID-19, including 2,251,613 deaths.Citation3 Currently, there is no clear recommendation for new corona pneumonia to receive antiviral treatment, thus vaccines are among the most promising effective strategies for preventing further COVID-19 outbreak.Citation4

Presently, there are 63 vaccines in clinical development and 175 vaccines in pre-clinical development.Citation5 Vaccines of Pfizer/BioNTech, Moderna, A-Z, Bharat and from China and Russia have been approved and are being used, other vaccines such as J&J and Novavax have also shown efficacy. In reality, a sufficiently high effective vaccine coverage rate could end the pandemic by generating herd immunity, thereby protecting everyone, including those who are still susceptible to the virus.Citation6 For the COVID-19 vaccine, herd immunity may be achieved firstly when at least 83% of people have immunity.Citation2 Therefore, after the clinical trials of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, it will also face the challenge of its acceptance by the general population in a post-crisis context.Citation7 However, information spreading through multiple channels could have a considerable impact on the acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine.Citation8 The accelerated pace of vaccine development might further heightened public hesitancy, and could compromise acceptance.Citation9

Multiple factors including personal risk perception, vaccination attitude or motivation, information sources, access channels and demographic variables, as well as social influence and practical factors all might affect vaccination decision.Citation10 However, at present, few studies have investigated the prevalence of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance, and their determinants,Citation11,Citation12 especially among Chinese general population. A study conducted among health care workers (HCWs) in China found that 76% of HCWs showed their willingness to receive the COVID-19 vaccination after introduction, which was higher than that for the general population (73%).Citation11 Another study reported that 80% of the Chinese public who participated in the survey preferred to receive the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine when it is available, and when analyzing key factors affecting their preference for COVID-19 vaccination, effectiveness, long protective duration, very few adverse events and being manufactured overseas ranked high on the list.Citation13 Therefore, addressing sociodemographic determinants relating to the COVID-19 vaccination may help to increase uptake of the global vaccination program to tackle future pandemics.Citation14

Moreover, China is one of the few countries recovering from the pandemic via careful maneuvering to return to normal. Nevertheless, the pandemic’s impact at the physical, psychological, social and economic levels is extensive and long-lasting. And the public’s acceptance as well as the willingness for COVID-19 vaccination may alter over time as the pandemic progresses.Citation13 At present, it is unclear whether a sufficient proportion of the population would decide to get vaccinated when a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine becomes available.Citation15 Hence, the primary purpose of our research is to investigate the willingness and acceptance of the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine among the adult general population in China, and to analyze related influencing factors and reasons. Additionally, we also investigated the participants’ general knowledge and perceptions of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, and sources of knowledge about vaccine, such as Internet, media, and family members, etc. Our research could provide empirical evidence to carry out more tailored interventions and policies to increase vaccination uptake of COVID-19 vaccine for the Chinese general population in future.

Materials and methods

Study design and ethical consideration

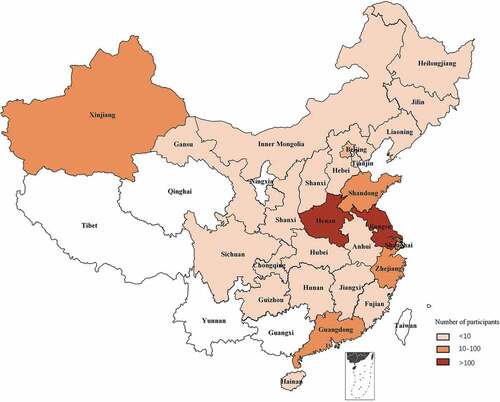

This cross-sectional study was conducted among Chinese adults aged 18 years old and above via anonymous online survey of the general population in China from September 8th to 15th, 2020. The survey was delivered to individuals through social networks and shared through the “Questionnaire Star” (URL: https://www.wjx.cn/m/90378737.aspx). The geographical location of the study areas was shown in the Appendix A. The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki by the World Medical Association and approved by the ethical committee of Soochow University. Participants provided informed consent under the condition of anonymity and confidentiality. Participation in the investigation was voluntary, without any form of coercion or compensation. Participant anonymity and confidentiality were kept throughout the research process.

Content of the study tool

On the basis of literature review, we developed a standardized questionnaire.Citation15–21 The survey comprised 23 closed-ended questions and took approximately 3 minutes to complete. The 23-item questionnaire was divided into three sections, including participants’ main demographic characteristics (i.e., gender, age, current city residence, education level and occupation, 7 items) and health-related information (i.e. COVID-19 infection and chronic diseases status defined by WHO including cardiovascular diseases, cancers, chronic respiratory diseases and diabetes, 2 items), the willingness to vaccinate the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine (1 item), sources of knowledge about SARS-CoV-2 vaccine (select all that apply: Internet, visits to healthcare providers, family members, friends, media, vaccine companies and industries, alternative healthcare providers such as acupuncturists, 1 item) and the acceptance of the vaccine (5-point scale, from very unlikely to very likely, 5 items), the summation of the acceptance score were derived ranging from 5 to 25. In addition, there were also 7 items related to general knowledge and perceptions of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. The survey was self-paced, so participants had enough time to read, understand, and answer all questions.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as median (interquartile range, IQR) for non-normally distributed data. Categorical variables were expressed as number (percentage). The comparison of the willingness and acceptance of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine inoculation stratified by sociodemographic and health-related characteristics including gender, age, current city residence, education, occupation, etc., were compared by performing Chi-square test. Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical variable of COVID-19 infection status, as well as non-parametric test for continuous variables of the acceptance of the vaccine. Items related to sources of knowledge about SARS-CoV-2 vaccine were analyzed separately using the Chi-square test to examine their association with gender, age, current city residence, education level, and occupation. Binary logistic regression analysis was performed to examine the association of sociodemographic and health-related factors with vaccination willingness and acceptance. Sociodemographic and health-related characteristics and SARS-CoV-2 knowledge were included as independent variables into the regression model, unadjusted and adjusted analyses generating odds ratios (OR), as well as 95% confidence intervals (CI) and p values were conducted. As for the acceptance, a score of ≤19 (i.e. the median of the acceptance score) was set a positive event (i.e., OR > 1, poor acceptance of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine inoculation). All analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 22.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, U.S.A.). A two-sided p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The comparison of the willingness and acceptance of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination stratified by sociodemographic and health-related characteristics

A total of 1045 questionnaires were collected, among which 983 completed questionnaires were included in the final statistical analysis. The effective rate was 94.1%. As shown in , male and female participants accounted for 46.6% and 53.4%, respectively. About 76.8% of the participants were between 18 and 30 years, and 23.2% of the participants were over 30 years. And 51.8% of the participants were from Jiangsu province, 29.9% were from Henan province and 18.3% were from other provinces. Among the participants, 88.3% of them had bachelor's degree or above, 83.1% were non-medical staff, and 69.6% were students. Five (0.5%) of them had ever been diagnosed with COVID-19 in their family, friends, or themselves, 31 (3.2%) participants were from high-risk areas, and 57 (5.8%) participants suffered from chronic diseases. According to China’s sixth census,Citation22 the population aged 18–30 years accounted for 21.7% of the total population, and those aged over 30 accounted for 57.3% of the total population; And among the population aged 18 and above, those with a bachelor degree or above accounted for 4.7% of the total population, and those with a bachelor degree below accounted for 94.2% of the total population. Therefore, our investigations likewise may suggest skewing of responders different from the general population.

Table 1. The differences in the willingness and acceptance of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine inoculation stratified by sociodemographic and health related characteristics

In terms of the willingness to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, participants with bachelor degree or above had higher willingness to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination than those with below bachelor degree (p = .004), whereas no difference in the willingness to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination was observed for other characteristics. In regards to the acceptance to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, female participants had higher acceptance score than male participants (p = .003), those aged above 30 years old had higher acceptance score than those aged ranging from 18 to 30 years old (p < .001). The acceptance score of people from Jiangsu Province was higher than those from Henan Province (p < .001). The acceptance score of participants with bachelor's degree or above were higher than those with below bachelor's degree (p = .003). Students had lower acceptance score than other occupations (p < .001). The acceptance score of medical staff was higher than non-medical staff (p < .001). For those who were willing to novel coronavirus vaccine inoculation, the acceptance score was also higher than those who weren’t willing to vaccine inoculation (p < .001). Participants with chronic diseases also had higher acceptance score than those without chronic diseases (p = .004). Additionally, there was no significant difference in vaccine acceptance between those who had COVID-19 infection history or not, and those who came from high-risk areas or not.

Respondents’ general knowledge and perceptions of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine

As shown in , 74.1% of the participants believed that SARS-CoV-2 was highly contagious, and more than half of the participants (52.3%) felt that they were at risk of contracting SARS-CoV-2. In addition, 41.4% of the participants felt that the impact of the new corona pneumonia pandemic on their lives was a little serious, while 41.5% of the participants believed that the impact of the new corona pneumonia pandemic on their lives was serious. And 87.1% of the participants believed that SARS-CoV-2 vaccine would not cause SARS-CoV-2 infection, and 81% of the participants believed that SARS-CoV-2 vaccine was safe and effective in preventing COVID-19. And 75.5% of the participants believed that pregnant women would transmit the SARS-CoV-2 virus to their fetuses or newborns, and 58.9% of them believed that pregnant women should not be vaccinated against COVID-19.

Table 2. Respondents’ general knowledge and perceptions of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine

The willingness and reasons of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine inoculation

A total of 799 (81.3%) were willing to be vaccinated against COVID-19. Among them, 92.6% of the participants believed that vaccination of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine could protect themselves and others, while only 9.4% of the participants thought that vaccination of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine was mandatory (for reasons such as work requirement) (). In addition, 184 (18.7%) participants were unwilling to be vaccinated against COVID-19, 62.5% of them believed that the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine might be unsafe, and 44.6% were worried about the potential side effects of the vaccine. Other important reasons for the reluctance to be vaccinated against COVID-19 included fear of injections (19.0%), belief in natural or traditional therapies (6.5%), general opposition to vaccination (5.4%), religious reasons (0.5%), and it was not recommended by the health authorities (5.4%), as well as no need to get vaccinated if other people had been vaccinated (7.1%) ().

Figure 1. Reasons and sources of knowledge about SARS-CoV-2 vaccine inoculation. The reasons why the participants were willing (a) or unwilling (b) to receive the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine and the corresponding numbers, as well as the numbers of participants who obtained vaccine knowledge from different sources (c)

Factors associated with the willingness and acceptance of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine inoculation

As illustrated in , as for factors associated with the willingness of vaccine inoculation, participants who were with bachelor degree or above (OR = 0.56, 95% CI: 0.34–0.91), and believed that SARS-CoV-2 vaccine would not cause SARS-CoV-2 infection (OR = 0.50, 95% CI: 0.32–0.79) were more willing to be vaccinated, and people who did not think that the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine was safe and effective in preventing COVID-19 (OR = 5.44, 95% CI: 3.77–7.87) were also less willing to be vaccinated against COVID-19 in the adjusted model.

Table 3. Binary logistic regression analysis for factors associated with the willingness and acceptance of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine inoculation

In regards to factors affecting the acceptance of vaccine inoculation, people who were over 30 years old (OR = 0.38, 95% CI: 0.21–0.69) and those who believed that the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine could not cause SARS-CoV-2 infection (OR = 0.52, 95% CI: 0.34–0.81) were more receptive to the vaccine. While people from Henan Province (OR = 2.49, 95% CI: 1.77–3.51), those who were unwilling to be vaccinated against COVID-19 (OR = 3.86, 95% CI: 2.54–5.87) and the people who did not suffer from chronic diseases (OR = 2.25, 95% CI: 1.19–4.24), as well as the subjects who did not believe that the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine was safe and effective in preventing COVID-19 (OR = 1.94, 95% CI: 1.31–2.88) had worse acceptance of the vaccine.

Sources of knowledge about SARS-CoV-2 vaccine

shows the distribution of different ways through which participants obtained vaccine information. In general, most participants usually got information about vaccines through the Internet (i.e., reliable websites) (88.3%) and the media (i.e., TV, radio, newspapers and magazines) (71.5%), while only a few people got access to vaccines through vaccine companies (10.5%) and alternative healthcare providers such as acupuncturists (3.3%). In addition, 26.2% and 26.1% of participants got information about vaccines through their family members and friends, respectively. There were also 49.1% of them consulting medical staff to get access to vaccines.

We further compared the sources of knowledge about SARS-CoV-2 vaccine by sociodemographic characteristics (i.e., gender, age, education level, occupation, and medical staff or not). As shown in , there were significant differences in age (p = .043) and education level (p = .007) in the approach of “Internet”. The proportion of participants aged “18–30” was higher than that of those aged “>30”. The proportion of people with “bachelor's degree or above” was higher than the proportion of people with “below bachelor's degree”. In the approach of “consulting family members”, the proportion of women was higher than that of men, the proportion of participants aged “18–30 years old” was higher than that of those aged “>30 years old”, and the proportion of persons with “below bachelor degree” was higher than that of people with “bachelor degree or above”. The proportion of students was higher than that of other occupations. There were differences in gender in the approach of “media” (p = .002), with women was higher than men. While in the ways of “consulting medical staff” (p < .001) and “consulting vaccine companies” (p = .008), the proportions of medical staff were higher than those of non-medical staff.

Table 4. The sources of knowledge about vaccine analyzed via sociodemographic characteristics

Discussion

In this on-line survey, we observed that the majority (more than 80%) of the participants were willing to receive the new corona-pneumonia vaccine. The education level and the perception of the vaccine were key factors for affecting the willingness rate; and the participants’ acceptance of the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine was also affected by the factors including age, city residence, the willingness to vaccinate, suffering from chronic diseases or not, and the perception of the vaccine. It is indicated from our study that we need to take into account the differences in sociodemographic and health-related characteristics of the population in the process of vaccine popularization.

Our study showed that most of the participants were aware of the strong infectivity of SARS-CoV-2 virus and thought that the epidemic had a certain impact on their work and life as reported in the literature.Citation22–25 What’s more, nearly half of the participants thought that they very unlikely or unlikely perceived risk of contracting SARS-CoV-2. It has been reported that the acceptance of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine was associated with perceived risk for COVID-19, it is also essential to increase the perceived risk in communities.Citation26 In general, most people had a positive attitude toward the vaccine. They believed that the vaccination of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine would not cause the infection of SARS-CoV-2 (87.1%) and the vaccine was safe and effective in preventing COVID-19 (81.0%). Moreover, more than two thirds of people thought that pregnant women would transmit SARS-CoV-2 virus to their fetuses or newborns, while less than half of them thought that pregnant women should receive the COVID vaccine. A study of SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnancy showed that around 1.9% of infants born to the women in the study tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. Currently, although many vaccine candidates are in clinical trials, no trials have been done in pregnant women,Citation27 our study also suggests that pregnant women should be included in properly designed vaccine trials, which has been proposed by Heath et al.Citation28

Concerning the willingness to get vaccinated, our results are similar to the results of the several surveys in European and North American countries. In a global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine, 71.5% reported they would be very or somewhat likely to take a COVID-19 vaccine; and 61.4% reported they would accept their employer’s recommendation to take a COVID-19 vaccine.Citation29 In the answer to whether you will be vaccinated with the vaccine which is proven to be safe and effective, China reported the highest proportion of positive reactions (88.6%) and the lowest proportion of negative reactions (0.7%).Citation29 In other European and American countries, about 75% of French people would agree to vaccinate.Citation7 And 85.8% of Australians said they would get the vaccine if it was available.Citation30 In the United States, 67% of people were willing to get the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine.Citation31 These studies show that many countries around the world have a positive attitude toward SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, and the Chinese people might be more accepting of the vaccine than other countries. This might in part reflect greater confidence in the government among Chinese general population. It has been reported that countries, where the acceptance rate of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine was more than 80%, were often Asian nations with strong trust in central governments (China, South Korea, and Singapore).Citation29

When analyzing the factors affecting the investigator’s willingness to vaccinate the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, we found that people with a bachelor's degree or above were more willing to vaccinate. This is similar to the results of previous studies.Citation14,Citation31 An American survey showed that Asians (81%) and university and/or graduate degree holders (75%) were more likely to receive vaccination.Citation31 A study in Saudi Arabia also indicated that people with a postgraduate degree or above (68.8%) were more willing to receive future COVID-19 vaccination.Citation14 It is likely that people with higher education levels acquire more professional knowledge about vaccines, and they tend to believe that the advantages of vaccination outweigh the disadvantages. Our findings also suggested that the popularization of vaccine knowledge among people with education level below bachelor's degree might play an important role in increasing the willingness to SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in the future.

When analyzing the surveyor’s acceptance of the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, we found that people over the age of 30 years had a higher acceptance rate than people aged 18–30 years. This is consistent with the result of the previous study, which showed that older people were more likely to receive the vaccine.Citation29 The fact that subjects aged more than 30 year-olds are more susceptible to COVID disease than those aged 18–30 year-olds, consequently, makes>30 more likely to accept COVID vaccine than 18–30s. It has been reported that there is an increased risk of death in infected individuals of the elderly or with chronic diseases (349, 99.1%).Citation11 Therefore, older people are more prone to be vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2 to avoid viral infections. The lower acceptance in Henan province compared with Jiangsu Province suggested that there might be certain regional and cultural differences in the acceptance of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. This is consistent with the result of a study in the United States.Citation31 In addition, our research found that people without chronic diseases had lower acceptance than those with chronic diseases. Through online and media reports, people have learnt that among people with preexisting comorbid conditions such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and chronic respiratory disease, the case-fatality rate of new coronary pneumonia has increased significantly.Citation32–34 Consequently, patients with chronic diseases might be more willing to improve their resistance to SARS-CoV-2 virus through vaccination. What is more, it is also likely that people who do not suffer from chronic diseases have better immunity and pay less attention to their own health than people with chronic diseases, the acceptance of vaccines is lower. Our research also found that people who believed that the vaccine would not cause SARS-CoV-2 infection and those who believed that it was safe and effective in preventing COVID-19 had a higher willingness and acceptance of the vaccine. This shows that a positive perception of the vaccine is a favorable factor for participant’s high acceptance. Collectively, our findings suggested that possessing a positive perception of vaccine, especially for those aged less than 30 years, or without chronic diseases might play decisive roles in improving the acceptance of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in Chinese population.

Moreover, our research showed that most people get information about vaccines through the Internet (reliable websites) and the media (television, radio, newspapers, and magazines). This is consistent with the result of another study, with more than 80% of respondents using social media as their main source of information about COVID-19.Citation35 Although social media can be used to rapidly circulate important information to the general public, this can cause anxiety and fear if misinformation and rumors are spread via social media.Citation36 Uncertainty and rapidly changing information may have exacerbated concerns about the virus.Citation37 A study had shown that through more contact with the media and concerns about the epidemic situation, vaccination intentions were predicted by greater exposure to media and worrying about outbreaks.Citation38 Additionally, through learning from previous infectious disease outbreaks and public health emergencies (including HIV, H1N1, SARS, MERS, and Ebola), the lesson reminds us that credible sources of information and guidance are the key to control the epidemic.Citation39 Our findings also suggested that spreading reliable information about COVID19 vaccine via the Internet and media might play important roles in improving the willingness and acceptance of the vaccine.

We also found that among the “Internet” sources, people aged 18–30 years old and people with “bachelor's degree or above” were more likely to choose this way to obtain vaccine information. This shows that young people born in the 1990s rely more on reliable websites to obtain the knowledge of vaccine, and a study in the United States also showed that Internet users were more likely to have at least a bachelor's degree.Citation19 In the way of “consulting family members”, women chose to consult their family more than men, which is in consistency with previous findings by Cao et al.Citation40 People between 18 and 30 years old, students and people with “below bachelor degree” were also more inclined to obtain vaccine information from their families due to age, range of activities and knowledge restrictions. Interestingly, the three groups mentioned above also have lower acceptance scores. This may be because many parents have a lower awareness of disease susceptibility, vaccine protection, and vaccine safety. For example, it has been found that parents who reported using the Internet to obtain information about vaccines were less likely to agree with accepted tenets of vaccine science, less likely to agree that children need or benefit from vaccines.Citation19 In terms of “media”, women were more inclined to obtain information through this way, possibly because women are more emotional and more sensitive to media reports. In the ways of “consulting medical staff” and “consulting vaccine companies”, just as Freed et al.Citation41 showed that health care providers were the most reliable source of vaccine safety information; medical staff professionals are more likely to consult professionals than non-medical staff. In addition, as Fu et al.Citation11 reported that 95% of the HCWs participated in the study thought it was necessary to receive the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, and other medical staff showed more positive perception of the risk evaluation of infection and confidence in the effectiveness and safety of vaccine,Citation11 so this may partly explain why medical staff in our study had a higher acceptance score than non-medical staff. However, it should be mentioned that as the pandemic continues, media fatigue (i.e., people become insensitive to ongoing information) may reduce the impact of mass media on people’s positive health behaviors, which may affect people’s willingness to vaccinate.Citation42

The current research had strengths and limitations. The biggest strengths were that our study was timely, and it was one of the few studies on the willingness and acceptance among Chinese adult population. However, limitations should also be considered. This is a web-based cross-sectional survey and our findings may be influenced by selection bias. For example, our research involved fewer regions, mostly concentrated in Jiangsu and Henan, and adults were recruited and surveyed online, most of which were concentrated in 18–30 years old and those had bachelor degree or above, which likewise may suggest skewing of responders different from the general population reported by China’s sixth census. Given that these groups (i.e., Bachelors, students, and 18–30 years) apparently were more likely to respond to the survey than the average citizen and thus be inclined to accept the vaccine. Consequently, the generalization of the findings requires caution. With the changes in the domestic epidemic situation and the assessment of the safety as well as effectiveness of the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, people’s vaccination willingness may change.

Conclusions

Age, education level, chronic disease status, and the perception of vaccine might be key factors affecting the willingness and acceptance of vaccine. The Internet and the media were main ways where people get information about vaccine. In the future, in order to improve the willingness and acceptance of vaccine in China, it is of great importance to spread the correct knowledge about vaccine via media and Internet and trigger positive perception of vaccine, especially by targeting those aged <30 years, or those with below bachelor degree, or without chronic diseases.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the participants of this study.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses.The species severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5(4):536–44. doi:10.1038/s41564-020-0695-z.

- Sanche S, Lin Y, Xu C, Romero-Severson E, Hengartner N, Ke R. High contagiousness and rapid spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(7):1470–77. doi:10.3201/eid2607.200282.

- WHO. WHO coronavirus disease (COVID-19) dashboard. [accessed 2021 Feb 4]. https://covid19.who.int/2020.

- Wong L, Alias H, Wong P, Lee H, AbuBakar SJH. The use of the health belief model to assess predictors of intent to receive the COVID-19 vaccine and willingness to pay. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16(9):2204–14. doi:10.1080/21645515.2020.1790279.

- WHO. Draft landscape and tracker of COVID-19 candidate vaccines. [accessed 2021 Jan 26]. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/draft-landscape-of-covid-19-candidate-vaccines.

- Fine P, Eames K, Heymann DJ. “Herd immunity”: a rough guide. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(7):911–16. doi:10.1093/cid/cir007.

- Detoc M, Bruel S, Frappe P, Tardy B, Botelho-Nevers E, Gagneux-Brunon A. Intention to participate in a COVID-19 vaccine clinical trial and to get vaccinated against COVID-19 in France during the pandemic. Vaccine. 2020;38(45):7002–06. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.09.041.

- Cornwall WJS. Officials gird for a war on vaccine misinformation. Science. 2020;369(6499):14–15. doi:10.1126/science.369.6499.14.

- Fadda M, Albanese E, Suggs LJ. When a COVID-19 vaccine is ready, will we all be ready for it? Int J Public Health. 2020;65(6):711–12. doi:10.1007/s00038-020-01404-4.

- WHO. Improving vaccination demand and addressing hesitancy. 2019 [accessed 2020 Oct 28]. https://www.who.int/immunization/programmes_systems/vaccine_hesitancy/en/.

- Fu C, Zheng W, Pei S, Li S, Sun X, Liu P. Acceptance and preference for COVID-19 vaccination in health-care workers (HCWs). medRxiv. 2020. doi:10.1101/2020.04.09.20060103.

- Thunstrom L, Ashworth M, Finnoff D, Newbold SC. Hesitancy towards a COVID-19 vaccine and prospects for herd immunity. SSRN Electron J. 2020. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3593098.

- Dong D, Xu R, Wong E, Hung C, Feng D, Feng Z, Yeoh E, Wong S, Policy H. Public preference for COVID-19 vaccines in China: a discrete choice experiment. Health Expect. 2020:1–36. doi:10.1111/hex.13140.

- Padhi BK, Al-Mohaithef M. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in Saudi Arabia: a web-based national survey. medRxiv. 2020. doi:10.1101/2020.05.27.20114413.

- Neumann-Böhme S, Varghese NE, Sabat I, Barros PP, Brouwer W, Van Exel J, Schreyögg J, Stargardt T. Once we have it, will we use it? A European survey on willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19. Eur J Health Econ. 2020;21(7):977–82. doi:10.1007/s10198-020-01208-6.

- Chor JS, Ngai KL, Goggins WB, Wong MC, Wong SY, Lee N, Leung TF, Rainer TH, Griffiths S, Chan PK. Willingness of Hong Kong healthcare workers to accept pre-pandemic influenza vaccination at different WHO alert levels: two questionnaire surveys. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed). 2009;339:b3391. doi:10.1136/bmj.b3391.

- Liu H, Tan Y, Zhang M, Peng Z, Zheng J, Qin Y, Guo Z, Yao J, Pang F, Ma T, et al. An internet-based survey of influenza vaccination coverage in healthcare workers in China, 2018/2019 season. Vaccines. 2019;8:1. doi:10.3390/vaccines8010006.

- Canning H, Phillips J, Allsup SJ. Health care worker beliefs about influenza vaccine and reasons for non-vaccination–a cross-sectional survey. J Clin Nurs. 2005;14(8):922–25. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01190.x.

- Jones A, Omer S, Bednarczyk R, Halsey N, Moulton L, Salmon DJ. Parents’ source of vaccine information and impact on vaccine attitudes, beliefs, and nonmedical exemptions. Adv Prev Med. 2012;2012:932741. doi:10.1155/2012/932741.

- Di Martino G, Di Giovanni P, Di Girolamo A, Scampoli P, Cedrone F, D’Addezio M, Meo F, Romano F, Di Sciascio MB, Staniscia T. Knowledge and attitude towards vaccination among healthcare workers: a multicenter cross-sectional study in a Southern Italian region. Vaccines. 2020;8:2. doi:10.3390/vaccines8020248.

- Martinello RA, Jones L, Topal JE. Correlation between healthcare workers’ knowledge of influenza vaccine and vaccine receipt. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2003;24(11):845–47. doi:10.1086/502147.

- Liu S, Ma ZF, Zhang Y, Zhang Y. Attitudes towards wildlife consumption inside and outside Hubei province, China, in relation to the SARS and COVID-19 outbreaks. Hum Ecol Interdiscip J. 2020:1–8. doi:10.1007/s10745-020-00199-5.

- Zhang Y, Ma ZF. Psychological responses and lifestyle changes among pregnant women with respect to the early stages of COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020. doi:10.1177/0020764020952116.

- Ma ZF, Zhang Y, Luo X, Li X, Li Y, Liu S, Zhang Y. Increased stressful impact among general population in mainland China amid the COVID-19 pandemic: a nationwide cross-sectional study conducted after Wuhan city’s travel ban was lifted. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020;66(8):770–79. doi:10.1177/0020764020935489.

- Zhang Y, Ma ZF. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and quality of life among local residents in Liaoning province, China: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:7. doi:10.3390/ijerph17072381.

- Harapan H, Wagner A, Yufika A, Winardi W, Anwar S, Gan A, Setiawan A, Rajamoorthy Y, Sofyan H, Mudatsir M. Acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine in Southeast Asia: a cross-sectional study in Indonesia. Front Public Health. 2020;8:381. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2020.00381.

- Amanat F, Krammer FJI. SARS-CoV-2 vaccines: status report. Immunity. 2020;52(4):583–89. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2020.03.007.

- Heath P, Le Doare K, Khalil A. Inclusion of pregnant women in COVID-19 vaccine development. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(9):1007–08. doi:10.1016/s1473-3099(20)30638-1.

- Lazarus J, Ratzan S, Palayew A, Gostin L, Larson H, Rabin K, Kimball S, El-Mohandes A. A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nat Med. 2020;15:e024001. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-1124-9.

- Dodd R, Cvejic E, Bonner C, Pickles K, McCaffery KJT. Willingness to vaccinate against COVID-19 in Australia. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020. doi:10.1016/s1473-3099(20)30559-4.

- Malik A, McFadden S, Elharake J, Omer SJE. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in the US. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;26:100495. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100495.

- Zhao X, Zhang B, Li P, Ma C, Gu J, Hou P, Guo Z, Wu H, Bai Y. Incidence, clinical characteristics and prognostic factor of patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. medRxiv. 2020. doi:10.1101/2020.03.17.20037572.

- Wu Z, McGoogan J. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the chinese center for disease control and prevention. Jama. 2020;323(13):1239–42. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.2648.

- Onder G, Rezza G, Brusaferro SJ. Case-fatality rate and characteristics of patients dying in relation to COVID-19 in Italy. Jama. 2020;323(18):1775–76. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.4683.

- Enitan SS, Oyekale AO, Akele RY, Olawuyi KA, Olabisi EO, Nwankiti AJ. Assessment of knowledge, perception and readiness of Nigerians to participate in the COVID-19 vaccine trial. Int J Vacc Immunization. 2020;4(1). doi:10.16966/2470-9948.123.

- Gao J, Zheng P, Jia Y, Chen H, Mao Y, Chen S, Wang Y, Fu H, Dai J. Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0231924. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0231924.

- Han P, Moser R, Klein WJ. Perceived ambiguity about cancer prevention recommendations: relationship to perceptions of cancer preventability, risk, and worry. J Health Commun. 2006;11(1):51–69. doi:10.1080/10810730600637541.

- Faasse K, Newby J. Public perceptions of COVID-19 in Australia: perceived risk, knowledge, health-protective behaviors, and vaccine intentions. Front Psychol. 2020;11:551004. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.551004.

- Siegrist MZA. The role of public trust during pandemics: implications for crisis communication. Eur Psychol. 2014;19:23–32. doi:10.1027/1016-9040/a000169.

- Cao Y, Ma ZF, Zhang Y, Zhang Y. Evaluation of lifestyle, attitude and stressful impact amid COVID-19 among adults in Shanghai, China. Int J Environ Health Res. 2020;undefined:1–10. doi:10.1080/09603123.2020.1841887.

- Freed G, Clark S, Butchart A, Singer D, Davis MJP. Sources and perceived credibility of vaccine-safety information for parents. Pediatrics. 2011. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-1722P.

- Collinson S, Khan K, Heffernan J. The effects of media reports on disease spread and important public health measurements. PLoS One. 2015;10(11):e0141423. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0141423.