ABSTRACT

Auto-disable (AD) syringes are specifically designed to prevent syringe reuse. However, the notion that specific AD syringe designs may be unsafe due to reuse concerns related to the syringe’s activation point has surfaced. We conducted a systematic review for evidence on the association between AD syringe design and syringe reuse, adverse events following immunization (AEFI), or blood borne virus (BBV) transmission. We found no evidence of an association between AD syringe design and unsafe injection practices including syringe reuse, AEFIs, or BBVs. Authors of three records speculated about the possibility of AD syringe reuse through intentionally defeating the disabling mechanism, and one hinted at the possibility of reuse of larger-than-required syringes, but none reported any actual reuse instance. In contrast to AD syringes, standard disposable syringes continue to be reused; therefore, the global health community should expand the use of AD syringes in both immunization and therapeutic context as an essential strategy for curbing BBV transmission.

Introduction

Syringe reuse, along with other unsafe injection practices, is a major contributor to a widespread spectrum of adverse effects including the global burden of blood borne diseases.Citation1–5 Despite substantial improvement in injection safety over the past two decades, unsafe injections remain prevalent, particularly in the Eastern Mediterranean region.Citation5 In 2010, an estimated 1.67 million hepatitis B virus (HBV) cases, 315,120 hepatitis C virus (HCV) cases, and 33,877 human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) cases were attributable to unsafe injection practices.Citation5 To curb the spread of blood borne diseases induced by unsafe injections, the World Health Organization (WHO), United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), and the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) jointly recommended the exclusive use of auto–disable (AD) syringes for immunization in 1999, which was updated in 2019.Citation6,Citation7 AD syringes incorporate a reuse prevention feature, which is meant to render the syringe unusable following the delivery of a single dose and thereby eliminate the risk of reuse. AD syringes are, therefore, a critical tool for combatting the spread of blood borne diseases. Despite the widespread use of AD syringes for the past two decades, there is limited research examining how well they have performed in the field with regard to eliminating the practice of syringe reuse.

WHO developed AD syringe specifications in the 1990s, which, in a process driven by WHO, was translated into an ISO standard in 2005; ISO 7886-3 Sterile hypodermic syringes for single use (Part 3: Auto-disable syringes for fixed-dose immunization).Citation8 In May 2020, an updated version of the ISO was released. However, both the 2005 and the 2020 ISO explicitly leave the syringe’s disabling feature’s design to manufacturer discretion.Citation8,Citation9 Therefore, although all AD syringes have an in-built disabling mechanism, syringes made by different manufacturers differ in terms of their specific design; for example, whereas in some AD syringes, the plunger breaks off to prevent reuse, others are disabled by a metal clip.Citation10 AD syringes also differ in terms of the disabling feature’s activation point, with the activation mechanism engaging at different points of injection administration.Citation10 As of August 2020, there were 46 AD syringes prequalified by WHO.Citation11 The WHO specification and subsequent ISO standard catalyzed the extensive use of AD syringes across the globe. Between 2001 and 2010, AD syringes were used to vaccinate 900 million persons across 60 countries through the Gavi supported Measles Initiative.Citation12 In 2017, UNICEF supplied >600 million 0.5 ml AD syringesCitation13 and, at present, supplies AD syringes to 89 countries (either as a donation or through procurement services). In 2017, 65 million children were vaccinated through Gavi supported programs alone.Citation14

Although several studies have pursued essential questions pertaining to AD syringes, such as how cost-effective they are,Citation15,Citation16 and how they can be leveraged to improve vaccination coverage,Citation17 studies showing the impact of different designs of AD syringes on unsafe injection practices, including syringe reuse, currently do not exist. The notion that specific AD syringe designs are unsafe due to reuse concerns and should be disqualified warrants a comprehensive review for empirical evidence; the decision to discontinue any of the AD syringe designs should not be made lightly due to global health policy implications, including inadvertently leading to manufacturer monopoly in the domain.

We sought to conduct a systematic literature review of published literature with the primary objective to identify any evidence of unsafe injection practices associated with any AD syringe design or activation point, including syringe reuse, Adverse Events Following Immunization (AEFI), and syringe-associated blood borne virus (BBV) transmission. As a secondary objective, to ensure a robust and thorough literature review, evidence of unsafe injection practices associated with standard disposable syringes including syringe reuse, AEFI, and BBV transmission was also included.

Methods

To comprehensively capture all adverse events and unsafe practices, we included disposable syringes and AD/RUP (Re-use prevention) syringes for both therapeutic and immunization purposes in our review. We searched research databases using preselected keywords and inclusion criteria.

Search strategy and selection criteria

We followed PRISMA guidelines for systematic review and reporting.Citation18 We searched the following nine databases between November 28, 2019, and March 31, 2020, without any date filters: PubMed, Cochrane, Medline, Google Scholar, EMBASE, Web of Science, Clinical trials registry, Vaccine Resource Library (VRL), and SYSVAC. We used the following search terms to identify literature on the intervention and outcomes of interest ‘auto-disable syringes’, ‘AD syringes’, ‘auto-lock syringes’, ‘auto-destruct syringes’, ‘disposable syringe’, ‘standard disposable syringes’, ‘non reusable syringes’, ‘reuse prevention syringes’, ‘RUP’, ‘RUP syringe’, ‘reuse’, ‘syringe reuse’, ‘unsafe syringe’, ‘unsafe immunization injection’, ‘unsafe injection practices’, ‘used syringe’, ‘blood borne diseases’, ‘blood borne virus’, ‘blood borne infection’, ‘HIV’, ‘HCV’, ‘HBV’, ‘adverse events’, ‘adverse effects’, ‘adverse events following immunization’, ‘AEFI’ and ‘side effects’. To ensure we captured syringe reuse in all contexts of health service provision (drug and insulin use by individuals in non-clinical settings were deemed outside the scope of this review), we added the following terms: ‘immunization’, ‘childhood immunization’, ‘routine immunization’, ‘childhood vaccination’, ‘medical injections’, ‘therapeutic injections’. We also conducted searches with terms such as ‘unnecessary injections’, ‘overuse of injections’, ‘irrational injections’, ‘shortage of injection equipment’, ‘stock out of injection equipment’, ‘unsterile injection equipment’, ‘sterile injection equipment’, ‘safe injection practices’, and ‘safety syringe’, to excavate any remaining relevant literature. We discarded results that were not in English. We included all study types in the review, including case-report, case-series, case-control, cohort, pre-post intervention, time-series analysis, qualitative analysis, randomized and non-randomized studies. We also examined clinical observations, scientific meeting abstracts, conference abstracts, papers and proceedings, fact sheets, dissertations, letters and commentaries, product patents, and policy documents identified through our searches. We defined records that were not studies and were searchable only through Google Scholar as gray literature, and removed them from our analysis.

Further clarity is required regarding the nomenclature of different types of syringes. Immunization syringes with a reuse prevention feature are often called auto-disable (AD) syringes, while therapeutic syringes with a reuse prevention feature are referred to as reuse prevention (RUP) syringes. A syringe with a sharp injury protection feature is called a sharp injury protection (SIP) syringe. However, many users, procurers, and even subject specialists mix these terms, and “AD syringe” remains a popular umbrella term for all syringes with a reuse prevention feature. These terms have been used in the WHO 2015 injection safety guidelines page #6 under the abbreviation and acronyms section.Citation19

Each record that remained after the titles and abstract had been screened independently by two researchers (Fatima Miraj (FM) and Mehr Munir (MM)) was evaluated further by performing a word search and examining the context in which keywords had been used to establish relevance. Bibliographies of all papers that fit our research criteria were examined to ensure no papers were missed. All studies that were retained and deemed necessary for full-text review by either one or both independent researchers by this point were reviewed in full by a third independent researcher (Anokhi Ali Khan (AAK)). Studies that met our inclusion criteria were summarized (Supplementary Table 1) and then graded using an adapted criterion from Atkin et al.Citation20 (Supplementary Table 2), which takes into account methodology variation between and within studies. Our scoring system allowed us to evaluate the quality of each included study according to the following components: (1) research rigor, demonstrated by a clearly defined research question, description of study design, sampling strategy, and method of data collection; (2) description of study context and assessment of generalizability of results; (3) clear description of analysis methods; (4) credibility of results in light of the evidence generated; (5) depth and richness of findings demonstrated by a sustained reflection on the different perspectives, an examination of underlying factors, and discussion of conceptual linkages; and (6) relevance in terms of a discussion on AD syringes. In addition, we included criterion of study type in the scoring, with a double blinded clinical trial scoring the highest and commentary the lowest. Robustness and validity of statistical methods were also evaluated based on whether confounders were taken into account and if study power was calculated. The maximum possible score for a single study was 19. The scoring criteria were used to distinguish between records in terms of rigor, relevance, and credibility of results and allowed us to compare results and conclusions objectively.

This study was registered with PROSPERO, CRD42020165528.

Results

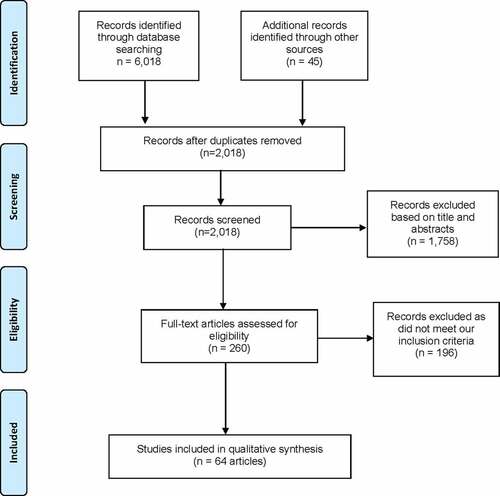

We identified 6,063 articles, and following de-duplication, 2,018 articles were reviewed (). We excluded 1,758 records based on title or abstract screening. Of the 260 articles on the list, 196 were removed following the third reviewer’s full-text review as they did not meet our inclusion criteria. The final review included 64 records, of which 55 were original research articles, and nine were commentaries,Citation21,Citation22 editorials,Citation23 news reportsCitation24,Citation25 or bulletins,Citation26,Citation27 essays,Citation28 or WHO guidelines.Citation19

A list of all included records is provided in , along with their associated region and year of data collection. Study characteristics are summarized in Supplementary Table 1 (Appendix). The score range of included records is 0–15, with individual scores provided in Supplementary Table 2 (Appendix). Included studies’ year of completion ranged from 1991 to 2019, with 18 of the 55 research studies having been performed before the GAVI Alliance’s safety support program was initiated in 2002 (to introduce/increase the use of AD syringes in national immunization programs).Citation29 Of the included research studies, 28 studies were prospective, while 27 were retrospective. Furthermore, 27 studies incorporated a substantial qualitative component,Citation30–56 encompassing structured observations of healthcare facility practices and vaccine administration, and/or interviews with health-care workers (HCWs). Research sites of included studies were spread across eighteen countries, including China,Citation42,Citation52,Citation57 Swaziland,Citation36 Egypt,Citation38,Citation51,Citation58 Pakistan,Citation21,Citation40,Citation43,Citation48,Citation53,Citation54,Citation59–63 Cameroon,Citation45 Burkina Faso,Citation64 India,Citation37,Citation46,Citation49,Citation50,Citation65–71 Mongolia,Citation41 Nepal,Citation31,Citation39 Ethiopia,Citation32,Citation47 Ghana,Citation55 Moldova,Citation72 Korea,Citation73,Citation74 Yemen,Citation75 Cambodia,Citation76 Nigeria,Citation30,Citation56 Bangladesh,Citation35 and Kenya.Citation33,Citation34,Citation44 Additionally, a multi-country evaluation of injection practices was included in our review.Citation2,Citation5,Citation77–79 The total number of injections observed by the combined studies was an estimated 38,000, and the total HCWs interviewed were more than 5,000. The range of prevalence rates of syringe reuse, AEFIs, and syringe-associated BBVs is provided in .

Table 1. Overview of included records by region, timeline and key topics covered

Table 2. Range of prevalence rates of syringe reuse, AEFIs, and syringe–associated BBVs reported by included records

Unsafe practices associated with AD syringe or AD syringe activation point, including reuse, AEFI, and BBV transmission

Of the 55 studies accepted in our review, none reported successful or attempted reuse of AD or RUP syringes in the field, or any correlation between AD/RUP syringes and AEFI and BBV transmission. One study (grade = 12) conducted in Karachi, Pakistan, mentioned AD syringe reuse in experimental settings, reporting that when vaccinators were specifically challenged to defeat the disabling mechanism of an AD syringe called SoloShot, a few were successful in doing so by removing the locking clip.Citation59 A quality control issue regarding SoloShot was also noted, as 0.4% of 2,400 AD syringes were missing the locking clip, rendering them potentially reusable. The study was conducted prior to the ISO, in 1995, and stated that modifications in design have since been made to eliminate AD syringe tampering possibilities. The authors concluded AD syringes are safe and effective regardless of the vaccinator’s experience or training. The study did not comment on the syringe’s activation point. Bandyopadhyay et al. (grade = 3) reviewed two different designs of AD syringes in 2005 and reported a possibility of reuse by not activating or disabling the locking device in the two designs of AD syringes. However, this was a low-scoring article, where the author only discussed hypothetical ways to defeat the locking mechanism of different designs, instead of citing any evidence. Additionally, the article was published prior to the introduction of WHO ISO standards in 2005.Citation26

In an opinion piece from 2013, Altaf (grade = 1) expressed concerns that someone may intentionally avoid fully pulling the plunger of an AD syringe, thus preventing the locking mechanism from being triggered.Citation22 However, this record scored low on our grading criteria, and the activation point of AD syringes was also not discussed. Murakami et al. (grade = 14) similarly speculated that if AD syringes of all sizes become commercially available, vaccinators could intentionally obtain larger-than–required syringes and potentially reuse them between clients.Citation42 Even though this study was evaluated as a higher quality study according to our grading criteria, the author did not study reuse or find any evidence associated with it, but only hypothesized that the potential for reuse might exist in reference to different sized AD syringes.

In contrast, authors of three studies confirmed the effectiveness of AD syringes in limiting reuse and reducing BBV transmission through directly examining AD syringes’ impact on disease trends and injection practices.Citation2,Citation52,Citation57 They were relatively high-quality studies that scored the grades of 14 and 15 according to our criteria. Authors of 10 additional studies called for the expansion of AD syringe use based on their findings regarding syringe reuse and BBV disease prevalence, but did not themselves investigate or quantify AD syringes’ impact on injection safety.Citation21,Citation33,Citation36,Citation50,Citation52,Citation54,Citation62,Citation64,Citation79,Citation80

Furthermore, among the editorials, commentaries, news reports and bulletins included in our review, five supported the adoption of AD syringes as an effective strategy for combatting unsafe injections.Citation23,Citation24,Citation27,Citation28,Citation81

Unsafe practices associated with disposable syringes including reuse, AEFI, and BBV transmission

The reuse rates for standard disposable syringes reported by the included studies ranged from 0.1% to 94.4% (). The highest reported reuse (94.4%) was from a study conducted across 18 health facilities in Karachi, Pakistan, in 1995 (grade = 14).Citation40 The figure was derived from data obtained through questionnaires and observations conducted at 18 health facilities with 135 patients. An additional ten studies from Pakistan, conducted between 1995 and 2013Citation43,Citation48,Citation53,Citation54,Citation60–62,Citation80,Citation82,Citation83 reported high rates of disposable syringe reuse, and drew attention to the persistence of unsafe injection practices in the country. The most recent study was by Yousafzai et al. in 2013 (grade = 12),Citation53 which reported a syringe reuse rate of 74.8%, based on interviews of 317 practitioners in Karachi, Pakistan. In addition to syringe reuse, unsafe injection practices found by authors of two additional studies (grades 12 and 13) included attempts at sterilizing disposable syringes with water, alcohol swabs, or disinfectant.Citation48,Citation82

Studies examining injection practices in India, conducted between 1995 and 2013,Citation37,Citation46,Citation49,Citation50,Citation65–70 also reported high rates of reuse. Prevalence of unsafe injection practices, including disposable syringe reuse, reported by Pandit et al. (grade = 10), was 77.0%. The study was performed in Gujarat State in 2004, and data was collected through questionnaires circulated amongst 510 families and it was found that unsafe injection practices were more common in government facilities (84.0%), as compared to private (71.0%) setups.Citation46 In another study from 2004, Arora et al. (grade = 14) estimated that of the 3 billion injections given in India annually, 1.89 billion were unsafe.Citation65 The majority of unsafe practices were occurring in immunization clinics, where 74.0% of the injections either carried a potential risk of BBV transmission or were administered with a faulty technique.Citation65 The most recent study from India was conducted in Gujarat in 2013 by Shah et al. (grade = 15), in which 6.8% of health-care workers mentioned having used an open or already used syringe or needle. The authors noted that during the study, 96.8% of the 251 participating HCWs had access to AD syringes.Citation50

In the earliest of the three studies from China,Citation42,Citation52,Citation57 Murakami et al. reviewed the prevalence of unsafe injection practices and contributing factors among vaccinators in North–Western China in 2000. The authors reported an estimated rate of 7.2–55.0% of syringe/needle reuse without sterilization, and an 8.9-23.3% rate of inappropriate use of disposable syringes/needles. The annual number of HBV infections in children due to unsafe immunization injections was estimated at 135– 3,120 per 100,000 fully immunized children.Citation42 In a study conducted ten years later, in 2010, Wu et al. (grade = 15) reported significant progress had been achieved in immunization safety as a result of a five-year financial support plan by GAVI, which helped to accelerate the introduction and uptake of AD syringes in the country. Over 70.0% of facilities in Western and Central China, and 25.0% in Eastern China, were using AD syringes. Of the 251 health-care providers included in the study, less than 0.5% attempted to re-sterilize disposable syringes. This was a higher graded study where reuse or attempted re-sterilization of AD syringes was not reported.Citation57

The reuse of disposable syringes on the same patient was reported in three studies. Of these, one was conducted in Mongolia in 2001 (grade = 13),Citation41 the second in Yemen in 2006 (grade = 13),Citation75 and the third in Nepal in 2014 (grade = 14).Citation39 These studies scored relatively higher on our grading criteria and attributed reuse to health-care workers’ lack of knowledge regarding reuse and blood borne infection. Abkar et al. from Yemen (grade = 13), despite recording one of the lowest rates of reuse (0.1% of 919 injections observed in health centers, and 1.2% of 827 injections observed in hospitals), 4.4% of injection providers stated they reused the syringe when providing multiple injections to the same patient.Citation75 Workers from Nepal also mentioned the sale of used syringes in the market.Citation39 A study showing needle reuse on three consecutive patients, especially among poorer patients in Bangladesh (grade = 15), reported that the lower–income groups were at a higher risk of BBV due to needle reuse.Citation35

Of the 11 studies from Africa, conducted between 1991 and 2019Citation30,Citation32,Citation33,Citation36,Citation44,Citation45,Citation47,Citation55,Citation56,Citation64,Citation77 reported rate of reuse of disposable syringes ranged from 2.0-60.0%. One study by Dicko et al. (grade = 9) compared survey results of the AFRO Logistics Project across 13 African countries, including Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Chad, Cote d’Ivoire, Ethiopia, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Rwanda, Senegal, Swaziland, Uganda, United Republic of Tanzania, and Zambia.Citation77 The importance of injection safety policy was highlighted, as disposable syringe reuse was reported to be more than double in Swaziland (39.0%), which had no injection safety policy, compared to Cote d’Ivoire (15.0%) where a policy was in place; with both countries reporting no shortage of equipment. Injection-related abscess was also reported in Cote d’Ivoire. In the remaining countries, the use of both disposable/sterilizable equipment was reported, with Chad being the poorest performer, at 60.0% reuse without sterilization or inappropriate sterilization of disposable injection equipment.Citation77 This was a relatively lower quality study, with no mention of the reuse of AD syringes.

Across the region, in Ethiopia,Citation32,Citation47 a 10.0% drop in reported disposable syringe reuse (from 12.0% to 2.0%) was noted between 2002 and 2018. The studies were given scores of nine and twelve, respectively. Studies from Kenya, in contrast, indicated an increase of syringe reuse being reported.Citation33,Citation44 These studies were also evaluated to be of higher quality than those conducted in Ethiopia, according to our grading criteria. In 2011, Chemoiwa et al. (grade = 15) reported that among 355 injections observed, 5.1% were with reused disposable syringes and new needles, and 2.8% were with reuse of both needle and syringe.Citation33 In a later study, conducted by Mweu et al. (grade = 12) in 2012, a higher reuse rate of 11.1% was reported, also based on direct observations.Citation44 In a 2006 study, performed by Musa et al. (grade = 12) in Nigeria, reuse was observed at nine of the thirteen immunization centers in the study, and the authors emphasized the importance of health education of workers.Citation56 In another study from Nigeria, published in 2019, Abubakar et al. (grade = 15) echoed the need for adequate training on injection practices, and reported that of 80 health workers, 37.5% did not always use a new syringe and needle.Citation30

In a study conducted in Egypt by Ismail et al. in 2003 (grade = 13), 13.2% of the 11,000 HCWs interviewed reported reusing syringe or needle, even though 95.7% of the injections observed by study investigators were with new disposable syringes. In addition, most providers did not adhere to other safe injection practices, as open containers and overflowing bins were seen in the preparation areas.Citation58 Among the studies reporting low reuse rates,Citation74,Citation75 one was conducted in Korea by Lee et al. (grade = 15), showing a 1.3% reuse rate of injections while replacing needles,Citation74 and the other one was by Abkar et al. in Yemen, who observed a 0.1% reuse rate in health centers, and a 1.2% reuse rate in hospitals.Citation75

Six studies,Citation54,Citation61,Citation72,Citation73,Citation76,Citation80 of which three were from Pakistan, examined the association between syringe reuse and risk of blood borne infection (BBI). In one of the studies from Pakistan, Ahmed et al. (grade = 14) reported a 4.5 times higher risk of BBI in patients having received >10 therapeutic injections over the past 10 years.Citation80 The case-control study by Hutin et al. (grade = 12), conducted in Moldova in 1995, reported that children who were HBsAg positive were more likely to have received injections from a hospital in the six months before illness compared to controls (stratified Odds ratio 5.2).Citation72 One study from Korea in 2015 (grade = 11),Citation73 and one from Cambodia in 2016 (grade = 7),Citation76 linked HCV and HIV outbreaks to possible syringe reuse. When studying patients with HIV in India (2005), Correa et al. reported 80% of the HIV positive patients had received up to 300 injections in the previous five years before testing positive, with one patient noting that a nurse retained the disposable syringe for reuse.Citation66 The study scored 14 according to our grading criteria and was considered to be of higher quality.

Three studiesCitation5,Citation78,Citation79 constituted a review and analysis of District Health Surveys (DHS) from lower middle-income countries (LMICs). Though a drop of 34.3% in syringe reuse had been recorded between 2000-2010,Citation5 in 2017, one in every 29 injections given in LMICs was considered unsafe. The Eastern Mediterranean Region had the highest unsafe injections per person per year, and Pakistan and Afghanistan had the least reliable access to new syringes.Citation78,Citation79 These studies were regarded as moderate to high quality based on their scores ranging from 11 to 14.

Additionally, a recent news article from British Medical Journal (BMJ) reported an HIV outbreak in Pakistan in 2019, which was linked to syringe and IV reuse, and affected >900 children.Citation25 However, as a news article, this record scored the lowest (zero) on our grading criteria.

Discussion

In this systematic review, we found no empirical or anecdotal evidence of an association between AD syringes of any design, and risk of syringe reuse, AEFI, or BBV transmission. Despite some speculation about the possibility of AD syringe reuse, actual reuse of an AD syringe of any design has never been reported, even after billions of AD syringe-administered injections over two decades globally. A specific discussion regarding AD syringes’ activation point does not appear at all in the literature, and of authors who recommend increased use of AD syringes, none mention any preference with regard to syringe design, including in terms of the activation point. Our review confirms that AD syringes are reliable and effective, and concerns regarding the safety of specific designs, including those related to the activation point, are not backed by the evidence. Regarding standard disposable syringes, however, our review demonstrates unsafe injection practices abound in LMICs, and risk of BBV transmission remains high. Millions of new BBV cases are attributed to unsafe injections each year, with over 1.6 million cases of hepatitis B virus alone.Citation1,Citation5,Citation84

There is sufficient evidence in the literature, based on higher quality studies from our review (grades 14 and 15), that highlight the importance of AD syringe in preventing/eliminating reuse.Citation33,Citation50,Citation52,Citation54,Citation64,Citation80 However, some authors have nevertheless speculated that the reuse of AD syringes by vaccinators and other health personnel could occur.Citation22,Citation26,Citation42 In the discussion section of their paper, Murakami et al. briefly discuss the possibility of AD syringe reuse, expressing the concern that if AD syringes are made commercially available, vaccinators may deliberately use larger volume RUP therapeutic syringes, and reuse the syringe between infants without activating the locking mechanism.Citation42 There is, however, no empirical evidence that leads the authors to consider this possibility, and therefore remains a conjecture. In a commentary on unsafe injections in Pakistan (grade = 1), Altaf et al. raise a similar concern, stating that someone who wishes to reuse an AD syringe may intentionally pull the plunger only partially during the first injection, and then reuse the syringe.Citation22 However, the authors’ concerns are centered on quality deficiencies and lack of manufacturer compliance with ISO standards rather than the activation point. The article by Bandyopadhyay et al. (grade = 3) critiques two AD syringes of different designs, one of which seems to have a late activation point, though the term ‘activation point’ is not used.Citation26 The authors contend that the plunger may be pulled back up for one of the two designs if the health worker deliberately does not deliver a full dose when administering the first dose. And for the other design, it may be possible to defeat the locking mechanism by applying pressure to the syringe at a particular angle. However, the article does not cite any actual instance of reuse of AD syringes of any design and precedes the introduction of the ISO standards. Additionally, the authors do not suggest changing the syringe’s activation point, recommending instead that inability to pull the plunger back up should be ensured for one of the designs, and a different plastic material should be considered for the other design.

Another study that briefly discusses AD syringe safety in terms of reuse probability is an early trial conducted by Steinglass et al. in Karachi in 1995.Citation59 In the trial, the authors investigated the safety, effectiveness, and ease of use of a RUP called SoloShot. According to the study, although reuse was not observed during any actual injection, vaccinators were able to remove the syringe’s safety clip when specifically challenged to do so. However, Steinglass et al. concluded that AD syringes should replace disposable injection devices in immunization programs, noting that the design had been modified to prevent reuse. Furthermore, another trial that tested the SoloShot in the context of an immunization campaign in Indonesia evaluated the device highly positively, noting its contribution to injection safety as well as vaccine savings.Citation85 In total, only four (two of which were low-scoring) of the 64 records made any reference to AD syringe reuse;Citation22,Citation26,Citation42,Citation59 two discussed the potential of design flaws conducive to reuse practices, but they were prior to the introduction of ISO standards,Citation42,Citation59 and one of the two studies specifically noted that the syringe’s design has since been rectified.

In view of the literature reviewed for this study and cited above, it is pertinent to mention that specific user-intent to misuse an AD syringe can render it re-usable, therefore effectively meaning that these devices’ AD mechanism can be intentionally defeated.Citation26,Citation59 The trial by Steinglass et al.Citation59 in Karachi demonstrated how vaccinators could be challenged to intentionally defeat the AD locking mechanism. An additional instance of intentional misuse can occur if the user administers a first large dose less than the maximum dose, creating an opportunity for potential reuse of the syringe before the locking mechanism is activated.Citation59 Intentional misuse can therefore render the AD syringe inoperable; however, in the absence of such malpractice, on the whole, AD syringes can reliably prevent reuse, with odds of reuse of AD syringes being much lower than standard disposable syringes. Taken in its entirety, therefore, the review on AD syringes suggests that the activation point is not a matter of concern, and the focus should lie on ensuring compliance with the ISO standard rather than modifying it. Unless there is a quality control failure, ISO-compliant AD syringes significantly improve the chances of safe injection practices, meeting the WHO criterion of causing no harm to recipient or provider. Concerns that linger after AD syringe introduction are about waste disposal, unregulated markets, financial constraints, irrational injections, and lack of monitoring rather than activation point.Citation6,Citation27,Citation86–91 Injection safety experts have therefore called for global and national programs to address these issues, through better policies, and implementing strategies such as bundling (AD syringes, vaccines, and safety boxes supplied as a bundle), behavior change interventions, and enforcement of safe waste management protocols.Citation6,Citation27,Citation86–88,Citation92

Despite the near-universal endorsement of AD syringes, a risk assessment study has been proposed to investigate whether the timing of the activation point is associated with the risk of reuse.Citation13 Risk of reuse will be determined by asking participating health workers which of the three different designs of syringes being tested (with disabling mechanism activation points at the beginning, middle, and end of injection) can be reused, demonstrating how each syringe can be reused, and then asking the participants to attempt reuse. However, in addition to lacking a rationale and relying on a methodology that assumes all designs of AD syringes are potentially reusable, such a study would run counter to the principles of risk assessment and WHO’s infection control policy, which recommends beginning with an initial assessment such as this review.Citation88

Given the research findings on AD syringes and the prevalence of standard disposable syringe reuse with widespread breaches of WHO guidelines regarding safe injection practices,Citation93 clear priorities emerge for a holistic injection safety strategy. Firstly, quality control mechanisms and provider monitoring tools need to be established, which include market regulation. Every injection device that is available in the market must be registered and adhere to stringent quality control standards to ensure ISO standard compliance. Policies and regulations must also consider informal providers, including traditional healers and birth attendants.Citation89 Secondly, waste disposal methods must be standardized and enforced. The problem of unsafe disposal could escalate when AD syringes become more prevalent, putting the community at increased risk.Citation30,Citation36,Citation90 Additionally, donors and international agencies need to facilitate the use and safe disposal of AD syringes in LMICs, through mitigating cost concerns, enabling the transfer of production technology, and adopting the ‘bundling’ policy. Finally, educational and community-level approaches are required to curb irrational use of injections, counter unawareness of both patients and providers, and change the norms which cause syringe reuse to persist.

The present review is a comprehensive study designed to systematically examine whether unsafe injection practices or AEFIs have any association with AD syringes’ activation point. However, it does have some limitations. Firstly, we were unable to obtain English-language translations of 48 records found through our literature search. However, the non-English papers that could not be reviewed constitute less than 1% of total records found. Furthermore, papers included in our review cover LMICs from all regions; therefore, it is unlikely that we missed evidence from a particular region or country due to the language barrier. In addition to the language limitation, differences in study design, methods, and populations made inference of change in reuse behavior over time in the same region difficult.

Conclusion

Our comprehensive systematic review confirms AD syringes are safe and effective irrespective of design, including activation point. No empirical or anecdotal evidence exists of the reuse of AD syringes of any design by any injection provider. However, the risk for reuse of standard disposable syringes in LMICs remains considerably high. We recommend that the global health community should stay focused on achieving universal and exclusive use of AD syringes in both immunization and therapeutic contexts, without prioritizing any AD syringe design based on its activation point. Additionally, safe waste disposal mechanisms, strict market checks, and strategies for rationale injection use should be adopted.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflict of interest. The funder of this study had no role in study design, analysis, interpretations, or writing of the manuscript.

Author contributions

SC conceptualized and designed the study. AAK developed the methodology for data extraction. FM and MM undertook the literature review and shortlisted records for full-text review; SI assisted with the literature search. AAK, MM, and FM assessed the eligibility of shortlisted records, and AAK made the final decision regarding inclusion in this study. FM extracted relevant data from all included records graded by AAK, MM, and FM. AAK, MM, and FM wrote the first draft of the manuscript, with input from SC and DAS. SC, AAK, MM, and DAS finalized the manuscript with input from all authors.

Acronyms

Additional information

Funding

References

- Kazi W, Bhuiyan SU. A systematic review of the literature on the unsafe injection practices in the health-care settings and the associated blood-borne disease trend: experiences from selected South Asian countries. J Comm Prevent Med. 2018;1:1–17.

- Deuchert E, Brody S. Lack of autodisable syringe use and health care indicators are associated with high HIV prevalence: an international ecologic analysis. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17(3):199–207. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.09.005.

- Hutin YJF, Hauri AM, Armstrong GL, Hauri AM, Armstrong GL, Armstrong GL. Use of injections in healthcare settings worldwide, 2000: literature review and regional estimates. BMJ. 2003;327(7423):1075. doi:10.1136/bmj.327.7423.1075.

- Kane A, Lloyd J, Zaffran M, Simonsen L, Kane M. Transmission of hepatitis B, hepatitis C and human immunodeficiency viruses through unsafe injections in the developing world: model-based regional estimates. Bull World Health Organ. 1999;77:801–07.

- Pépin J, Abou Chakra CN, Pépin E, Nault V, Vermund SH. Evolution of the global use of unsafe medical injections, 2000–2010. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(12):e80948. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0080948.

- World Health Organization. United Nations Population Fund, United Nations Children’s Fund. Safety of injections: WHO-UNICEF-UNFPA joint statement on the use of auto-disable syringes in immunization services. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 1999. Available at https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/63650.

- World Health Organization, UNICEF. Joint policy statement. Promoting the exclusive use of injection safety devices for all immunization activities. World Health Organization; 2019 [Accessed 2019 Nov 10]. https://www.who.int/immunization/documents/policies/RUP_JointStatement.pdf?ua=1.

- ISO 7886-3:2005. Sterile hypodermic syringes for single use part 3: auto-disable syringes for fixed-dose immunization. 2005 [Accessed 2019 Nov 10]. https://www.iso.org/standard/36742.html.

- ISO 7886-3:2020. Part 3: auto-disable syringes for fixed-dose immunization. 2020 [Accessed 2020 Oct 25]. https://www.iso.org/standard/76605.html.

- PATH. Using auto-disable syringes. Module 5. [Accessed 2019 Dec 16]. https://path.azureedge.net/media/documents/SafeInjPDF-Module5.pdf.

- World Health Organization. Prequalified devices and equipment: productList. 2020 [Accessed 2020 Oct 10]. https://apps.who.int/immunization_standards/vaccine_quality/pqs_catalogue/categorypage.aspx?id_cat=37.

- GAVI. Injection safety efforts eliminate immunisation-related infections in sub-Saharan Africa. 2011 [Accessed 2019 Nov 20]. https://www.gavi.org/news/media-room/injection-safety-efforts-eliminate-immunisation-related-infections-sub-saharan.

- UNICEF Supply Division. Safe injection equipment: supply and demand update. 2018 [Accessed 2019 Dec 16]. https://www.unicef.org/supply/sites/unicef.org.supply/files/2019-06/safe-injection-equipment-SIE-supply-and%20demand-update.pdf.

- GAVI. Annual progress report. 2017. https://www.gavi.org/sites/default/files/publications/progress-reports/Gavi-Progress-Report-2017.pdf.

- Reid S. Estimating the burden of disease from unsafe injections in India: a cost-benefit assessment of the auto-disable syringe in a country with low blood-borne virus prevalence. Indian J Community Med. 2012;37(2):89–94. doi:10.4103/0970-0218.96093.

- Bahuguna P, Prinja S, Lahariya C, Dhiman RK, Kumar MP, Sharma V, Aggarwal AK, Bhaskar R, De Graeve H, Bekedam H. Cost-effectiveness of therapeutic use of safety-engineered syringes in healthcare facilities in India. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2020;18(3):393–411. doi:10.1007/s40258-019-00536-w.

- Drain PK, Ralaivao JS, Rakotonandrasana A, Carnell MA. Introducing auto-disable syringes to the national immunization programme in Madagascar. Bull World Health Organ. 2003;81:553–60.

- PRISMA. Transparent reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. [Accessed 2020 Jun 16]. http://www.prisma-statement.org.

- World Health Organization. WHO guideline on the use of safety-engineered syringes for intramuscular, intradermal and subcutaneous injections in health-care settings. World Health Organization; 2015 [Accessed 2019 Nov 20]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK305368/.

- Atkins S, Launiala A, Kagaha A, Smith H. Including mixed methods research in systematic reviews: examples from qualitative syntheses in TB and malaria control. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12(1):1–7. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-12-62.

- Janjua NZ, Khan A, Altaf A, Ahmad K. Towards safe injection practices in Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc. 2006. https://mail.jpma.org.pk/PdfDownloadsupplements/1.

- Altaf A, Vaid S. The Sindh disposable syringe act: putting the act together. J Pak Med Assoc. 2013;63:1425–26.

- Gisselquist D. Avoiding reused instruments for immunizations exposes unsolved problems. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2009;15(1):107. doi:10.1179/oeh.2009.15.1.107.

- Sharma DC. India to use AD syringes to stem infection from reused needles. Lancet Infect Dis. 2004;4(10):601. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(04)01168-5.

- Dyer O. HIV: doctor who reused needles is blamed as nearly 900 children test positive in Pakistani city. BMJ. 2019;367:l6284. doi:10.1136/bmj.l6284.

- Bandyopadhyay S, Singh A. How safe are auto disable (AD) syringes? Bulletin of postgratudate institute of medical education and reaserch. Chandigarh. 2005;39:17–21.

- Miller M, Pisani E. The cost of unsafe injections. Bull World Health Organ. 1999; 77(10): 808–11. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2557745/pdf/10593028.pdf

- Ahmad K. Pakistan: a cirrhotic state? The Lancet. 2004;364(9448):1843–44. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17458-8.

- Allegranzi B. The burden of unsafe injections worldwide: highlights on recent improvements and areas requiring urgent attention. World Health Organization; 2018 [Accessed 2019 Dec 16]. https://www.who.int/medical_devices/Sun_pm_SAF_2_ALLEGRANZI.pdf.

- Abubakar S, Usman R, Idris A, Haddad M, Mba C, Mba CJ. Knowledge and practice of injection safety among healthcare workers in a Nigerian secondary healthcare facility. Int J Infec Control. 2019;15(1):1–8. doi:10.3396/ijic.v15i1.004.19.

- Bhattarai MD, Wittet S. Perceptions about injections and private sector injection practices in central Nepal. 2000 [Accessed 2020 Jan 15]. http://www.vaccineresources.org/files/Nepal-Inject-Practices-RA.pdf.

- Birhanu D. Injection safety knowledge and practice among nurses working in Jimma university medical center; Jimma South West Ethiopia; 2018. J Comm Med Public Health Care. 2019;6(2):1–7. doi:10.24966/CMPH-1978/100045.

- Chemoiwa K, Mwaura-Tenambergen M. Injection safety practices among nurses in Kenyan public hospitals. Int J Professional Pract. 2018;6:15–22.

- Chemoiwa RK, Mukthar VK, Maranga AK, Kulei SJ. Nurses infection prevention practices in handling injections: a case of rift valley provincial hospital in Kenya. East Afr Med J. 2014;91:361–67.

- Chowdhury AKA, Roy T, Faroque ABM, Bachar SC, Asaduzzaman M, Nasrin N, Akter N, Gazi HR, Lutful Kabir AK, Parvin M, et al. A comprehensive situation assessment of injection practices in primary health care hospitals in Bangladesh. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):779. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-11-779.

- Daly A, Nxumalo MP, Biellik RJ. An assessment of safe injection practices in health facilities in Swaziland. South Afr Med J. 2004;94:194–97.

- Garapati S, Peethala S. Assessment of knowledge and practices on injection safety among service providers in east Godavari district of Andhra Pradesh. Ind J Comm Health. 2014;26:259–63.

- Kandeel AM, Talaat M, Afifi SA, El-Sayed NM, Abdel Fadeel MA, Hajjeh RA, Mahoney FJ. Case control study to identify risk factors for acute hepatitis C virus infection in Egypt. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12(1):294. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-12-294.

- Kaphle H, Poudel S, Subedi S, Gupta N, Jain V, Paudel P. Awareness and practices on injection safety among nurses working in hospitals of Pokhara, Nepal. Int J Med Health Sci. 2014;3:301–07.

- Khan AJ, Luby SP, Fikree F, Karim A, Obaid S, Dellawala S, Mirza S, Malik T, Fisher-Hoch S, McCormick JB. Unsafe injections and the transmission of hepatitis B and C in a periurban community in Pakistan. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78:956–63.

- Logez S, Soyolgerel G, Fields R, Luby S, Hutin Y, Soyolgerel G, Fields R, Luby S, Hutin Y, Fields R, et al. Rapid assessment of injection practices in Mongolia. Am J Infect Control. 2004;32(1):31–37. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2003.06.006.

- Murakami H, Kobayashi M, Zhu X, Li Y, Wakai S, Chiba Y. Risk of transmission of hepatitis B virus through childhood immunization in northwestern China. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(10):1821–32. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00065-0.

- Mustufa MA, Memon AA, Nasim S, Shahid A, Omar SM. Exposure to risk factors for hepatitis B and C viruses among primary school teachers in Karachi. J Inf Dev Countr. 2010;4(10):616–20. doi:10.3855/jidc.499.

- Mweu JM, Odero TMA, Kirui AC, Kinuthia J, Mwangangi FM, Bett SC, Musee CM. Injection safety knowledge and practices among clinical health care workers in Garissa provincial general hospital. East Afr Med J. 2015;92:26–34.

- Okwen MP, Ngem BY, Alomba FA, Capo MV, Reid SR, Ewang EC. Uncovering high rates of unsafe injection equipment reuse in rural Cameroon: validation of a survey instrument that probes for specific misconceptions. Harm Reduct J. 2011;8(1):4. doi:10.1186/1477-7517-8-4.

- Pandit NB, Choudhary SK. Unsafe injection practices in Gujarat, India. Singapore Med J. 2008;49:936–39.

- Priddy F, Tesfaye F, Mengistu Y, Rothenberg R, Fitzmaurice D, Mariam DH, Del Rio C, Oli K, Worku A. Potential for medical transmission of HIV in Ethiopia. AIDS (London, England). 2005;19:348–50.

- Raglow GJ, Luby SP, Nabi N. Therapeutic injections in Pakistan: from the patients’ perspective. Trop Med Int Health. 2001;6(1):69–75. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3156.2001.00653.x.

- Rajasekaran M, Sivagnanam G, Thirumalaikolundusubramainan P, Namasivayam K, Ravindranath C. Injection practices in southern part of India. Public Health. 2003;117(3):208–13. doi:10.1016/S0033-3506(03)00065-9.

- Shah H, Solanki H, Mangal A, Dipesh P. Unsafe injection practices: an occupational hazard for health care providers and a potential threat for community: a detailed study on injection practices of health care providers. Int J Health & Allied Sci. 2014;3(1):28. doi:10.4103/2278-344X.130607.

- Talaat M, El-Oun S, Kandeel A, Abu-Rabei W, Bodenschatz C, Lohiniva A-L, Hallaj Z, Mahoney FJ. Overview of injection practices in two governorates in Egypt. Trop Med Int Health. 2003;8(3):234–41. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.01015.x.

- Yan Y, Zhang G, Chen Y, Zhang A, Guan Y, Ao H. Study on the injection practices of health facilities in Jingzhou district, Hubei, China. Indian J Med Sci. 2006;60(10):407–16. doi:10.4103/0019-5359.27671.

- Yousafzai MT, Nisar N, Kakakhel MF, Qadri MH, Khalil R, Hazara SM. Injection practices among practitioners in private medical clinics of Karachi, Pakistan. East Mediter Health J. 2013;19(6):577–82. doi:10.26719/2013.19.6.570.

- Qureshi H, Bile KM, Jooma R, Alam SE, Afridi HUR. Prevalence of hepatitis B and C viral infections in Pakistan: findings of a national survey appealing for effective prevention and control measures. East Mediter Health J. 2010;16(Suppl):S15–23. doi:10.26719/2010.16.Supp.15.

- Cronin WA, Quansah MG, Larson E. Obstetric infection control in a developing country. J Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nurs. 1993;22(2):137–44. doi:10.1111/j.1552-6909.1993.tb01793.x.

- Musa OI, Parakoyi DB, Akanbi AA. Evaluation of health education intervention on safe immunization injection among health workers in Ilorin, Nigeria. Ann Afr Med. 2006;5:122–28.

- Wu Z, Cui F, Chen Y, Miao N, Gong X, Luo H, Wang F, Zheng H, Kane M, Hadler SC. Evaluation of immunization injection safety in China, 2010: achievements, future sustainability. Vaccine. 2013;31:J43–8. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.11.057.

- Ismail N, Aboul Ftouh A, El Shoubary W, Mahaba H. Safe injection practice among health-care workers in Gharbiya Governorate, Egypt. East Mediter Health J. 2007;13:893–906.

- Steinglass R, Boyd D, Grabowsky M, Laghari A, Khan M, Qavi A, Evans P. Safety, effectiveness and ease of use of a non-reusable syringe in a developing country immunization programme. Bull World Health Organ. 1995;73:57.

- Altaf A, Fatmi Z, Ajmal A, Hussain T, Qahir H, Agboatwalla M. Determinants of therapeutic injection overuse among communities in Sindh, Pakistan. JAMC. 2004;16:35–38.

- Aziz S, Khanani R, Noorulain W, Rajper J. Frequency of hepatitis B and C in rural and periurban Sindh. J Pak Med Assoc. 2010;60:853–57.

- Hoeve E, Codlin A, Jawed F, Khan A, Samad L, Vatcheva K, Fallon M, Ali M, Niaz K, McCormick J, et al. Persisting role of healthcare settings in hepatitis C transmission in Pakistan: cause for concern. Epidemiol Infect. 2013;141(9):1831–39. doi:10.1017/S0950268812002312.

- Khan A, Altaf A, Qureshi H, Orakzai M, Khan A. Reuse of syringes for therapeutic injections in Pakistan: rethinking its definition and determinants. East Mediter Health J. 2019;25:283–89.

- Fitzner J, Aguilera JF, Yameogo A, Duclos P, Hutin YJF, Aguilera JF, Yameogo A, Duclos P, Hutin YJF, Yameogo A, et al. Injection practices in Burkina Faso in 2000. Int J Qual Health Care. 2004;16(4):303–08. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzh052.

- Arora N. Injection practices in India. WHO South-East Asia J Public Health. 2012;1(2):189. doi:10.4103/2224-3151.206931.

- Correa M, Gisselquist D. Reconnaissance assessment of risks for HIV transmission through health care and cosmetic services in India. Int J STD AIDS. 2006;17(11):743–48. doi:10.1258/095646206778691068.

- Gupta E, Bajpai M, Sharma P, Shah A, Sarin S. Unsafe injection practices: a potential weapon for the outbreak of blood borne viruses in the community. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2013;3(2):177–81. doi:10.4103/2141-9248.113657.

- Lakshman M, Nichter M. Contamination of medicine injection paraphernalia used by registered medical practitioners in south India: an ethnographic study. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(1):11–28. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00426-8.

- Sarman Singh SND, Sood R, Wali JP, Sood R, Wali JP, Wali JP. Hepatitis B, C and human immunodeficiency virus infections in multiply-injected Kala-azar patients in Delhi. Scand J Infect Dis. 2000;32(1):3–6. doi:10.1080/00365540050164137.

- Atul K, Priya R, Thakur R, Gupta V, Kotwal J, Seth T. Injection practices in a metropolis of North India: perceptions, determinants and issues of safety. Indian J Med Sci. 2004;58:334–44.

- Kermode M, Holmes W, Langkham B, Thomas MS, Gifford S. Safer injections, fewer infections: injection safety in rural north India. Trop Med Int Health. 2005;10(5):423–32. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01421.x.

- Hutin YJ, Harpaz R, Drobeniuc J, Melnic A, Ray C, Favorov M, Iarovoi P, Shapiro CN, Woodruff BA. Injections given in healthcare settings as a major source of acute hepatitis B in Moldova. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28(4):782–86. doi:10.1093/ije/28.4.782.

- Chung Y-S, Choi JY, Han MG, Park KR, Park S-J, Lee H, Jee Y, Kang C. A large healthcare-associated outbreak of hepatitis C virus genotype 1a in a clinic in Korea. J Clin Virol. 2018;106(106):53–57. doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2018.07.006.

- Lee H-I, Choi J-E, Choi S-J, Ko E-B. Medication injection safety knowledge and practices among health service providers in Korea. Qual Improv Health Care. 2019;25(1):52–65. doi:10.14371/QIH.2019.25.1.52.

- Abkar MAA, Wahdan IMH, Sherif AAR, Raja’a YA. Unsafe injection practices in Hodeidah governorate, Yemen. J Infect Public Health. 2013;6(4):252–60. doi:10.1016/j.jiph.2013.01.003.

- Vun M, Galang R, Fujita M, Killam W, Gokhale R, Pitman J, Selenic D, Mam S, Mom C, Fontenille D, et al. Cluster of HIV infections attributed to unsafe injection practices - Cambodia, December 1, 2014-February 28, 2015. MMWR Morbidity Mortal Week Rep. 2016; 65:142–45.

- Dicko M, Oni AQ, Ganivet S, Kone S, Pierre L, Jacquet B. Safety of immunization injections in Africa: not simply a problem of logistics. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78:163–69.

- Adewuyi EO, Auta A. Medical injection and access to sterile injection equipment in low- and middle-income countries: a meta-analysis of demographic and health surveys (2010–2017). Int Health. 2020;12(5):388–94. doi:10.1093/inthealth/ihz113.

- Hayashi T, Hutin YJ-F, Bulterys M, Altaf A, Allegranzi B. Injection practices in 2011–2015: a review using data from the demographic and health surveys (DHS). BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):1–10. doi:10.1186/s12913-019-4366-9.

- Ahmed B, Ali T, Qureshi H, Hamid S. Population-attributable estimates for risk factors associated with hepatitis B and C: policy implications for Pakistan and other South Asian countries. Hepatol Int. 2013;7(2):500–07. doi:10.1007/s12072-012-9417-9.

- World Health Organization. Report of the first meeting of the steering committee on immunization safety. 1999 [Accessed 2020 Jan 11]. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/66328/WHO_V-B_00.17_eng.pdf.

- Zakar MZ, Qureshi S, Zakar R, Rana S. Unsafe injection practices and transmission risk of infectious diseases in Pakistan: perspectives and practices. Pak Vis. 2013;14:27–50.

- Janjua NZ, Mahmood B, Imran Khan M. Does knowledge about bloodborne pathogens influence the reuse of medical injection syringes among women in Pakistan? J Infect Public Health. 2014;7(4):345–55. doi:10.1016/j.jiph.2014.04.001.

- Kermode M. Unsafe injections in low-income country health settings: need for injection safety promotion to prevent the spread of blood-borne viruses. Health Promot Int. 2004;19(1):95–103. doi:10.1093/heapro/dah110.

- Nelson CM, Sutanto A, Suradana IG. Use of SoloShot autodestruct syringes compared with disposable syringes, in a national immunization campaign in Indonesia. Bull World Health Organ. 1999;77:29–33.

- World Health Organization. Medical device regulations: global overview and guiding principles. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2003 [Accessed 2020 Jan 20]. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42744.

- Simonsen L, Kane A, Lloyd J, Zaffran M, Kane M. Unsafe injections in the developing world and transmission of bloodborne pathogens: a review. Bull World Health Organ. 1999;77:789–800.

- World Health Organization. Aide-mémoire for a national strategy for the safe and appropriate use of injections. Geneva; 2000 [Accessed 2020 Mar 13]. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/66696.

- Reeler AV. Anthropological perspectives on injections: a review. Int J Public Health. 2000;141:135–43.

- Kuroiwa C, Suzuki A, Yamaji Y, Miyoshi M. Hidden reality on the introduction of auto-disable syringes in developing countries. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2004;35:1019–23.

- Hersh Bradley S, Carr Richard M, Fitzner J, Goodman Tracey S, Mayers Gillian F, Everts H, Laurent E, Larsen Gordon A, Bilous Julian B. Ensuring injection safety during Measles immunization campaigns: more than auto‐disable syringes and safety boxes. J Infect Dis. 2003;187(s1):S299–S306. doi:10.1086/368227.

- Lloyd JS, Milstien JB. Auto-disable syringes for immunization: issues in technology transfer. Bull World Health Organ. 1999;77:1001.

- World Health Organization. WHO best practices for injections and related procedures toolkit. World Health Organization; 2010 [Accessed 2020 Feb 25]. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44298/9789248599255_por.pdf.