ABSTRACT

The 2012 report of the President’s Cancer Panel highlighted the overriding contribution of missed clinical opportunities to suboptimal HPV vaccination coverage. Since then, it remains unknown whether the rates of provider recommendations for the HPV vaccine in the US population have increased. We conducted an analysis of four rounds of the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS), a household survey of civilian US residents aged 18 y or older. A total of 1,415 (2012), 1,476 (2014), 1,208 (2017), and 1,344 (2018) respondents to the HINTS survey who were either HPV vaccine-eligible or living with HPV vaccine-eligible individuals were included. Overall, the rates of providers’ recommendations remained stagnated from 2012 to 2018 in all categories of the study population, except for non-Hispanic Blacks (NHBs), where this prevalence increased during the study period (AAPC = 16.4%, p < .001). In vaccine-eligible individuals (18–27 y), declining trends were noted overall (AAPC = −21.6%, p < .001), among NHWs (AAPC = −30.2%, p < .001) and urban dwellers (AAPC = −21.4%, p < .001). Among vaccine-ineligible respondents (˃27 y) living with vaccine-eligible individuals, trends in the prevalence of provider recommendations for HPV vaccine were stagnating overall (AAPC = 0.5%, p = .90), and increasing only among NHBs (AAPC = 13.9%, p < .001). Despite recent progress, our findings indicate variations of trends in provider recommendations for the HPV vaccine in the US adult population according to age, sex, race/ethnicity, and residence. To accelerate HPV vaccination uptake, immediate actions to enhance provider recommendation for HPV vaccine are needed.

Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common sexually transmitted infection in the United States (US).Citation1,Citation2 Each year, approximately 34,800 cancers diagnosed in the US are attributable to HPV.Citation3 While the burden of these cancers – except for cervical cancer, for which population-based screening is available – has increased during the last decade,Citation4,Citation5 the rising incidences observed so far are projected to continue in the coming years.Citation6,Citation7 The long-term increase in HPV-related cancers could be drastically lowered by widespread administration of the HPV vaccine, a safe and effective tool that protects against HPV infection and related diseases.Citation8 In the US, the HPV vaccine was first approved in 2006 for use among females between the ages of 9 and 26 y.Citation9 HPV vaccine guidelines were later extended to males in 2009, with a routine vaccination recommendation beginning in October 2011.Citation10 Since 2017, the only HPV vaccine available in the US targets 7 high-risk viral types responsible for 92% of HPV-attributable cancers, in addition to 2 low-risk types that cause 90% of genital warts.Citation8 Despite this compelling evidence and the considerable efforts deployed nationwide to improve community access to this preventive service, HPV vaccines are underutilized in the US, and vaccination coverage remains far below the Healthy People (HP) 2020 goal of 80% among teenagers,Citation11 a targeted rate necessary to achieve substantial public health benefits. In 2018, only 51% of eligible US adolescents were up-to-date (UTD) on their vaccination schedule,Citation12 a relatively low rate in a country in the forefront of scientific breakthroughs and global initiatives to promote HPV vaccination. While a gradual increase in HPV vaccination uptake in the US has been observed over time,the HP 2020 goal was not met.

It is well established that recommendation by attending health-care providers is one of the strongest predictors of HPV vaccination uptake.Citation13–15 In its 2012 report to the White House, the President’s Cancer Panel acknowledged that underuse of HPV vaccines was a serious but correctable threat to progress against cancer.Citation16 The Panel stressed the need to accelerate HPV vaccination uptake through the dissemination of effective communication strategies targeting primarily health-care providers. By endorsing this call, several health professional societies, including the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), and the American College of Physicians (ACP) partnered with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Immunization Action Coalition (IAC) to strongly encourage their members to ensure that eligible patients are offered HPV vaccination in a timely manner.Citation17,Citation18 More recently, the 2018 report of the President’s Cancer Panel, in its renewed call to action, urged health-care providers to strongly recommend HPV vaccination for all eligible individuals.Citation19 Indeed, while a growing number of providers report having engaged in promoting HPV vaccination, many parents of vaccine-eligible adolescents do not recall the vaccine being recommended by their children’s health-care provider.Citation20,Citation21

Although sex-specific, ethnic, and racial disparities in receiving HPV vaccine recommendations have been previously observed,Citation22 it remains unclear whether these variations have changed over time. Previous reports on HPV vaccine recommendations by health-care providers have focused on parents/guardians of vaccine-eligible adolescents.Citation13,Citation23 However, trends in provider recommendations to vaccinate against HPV among vaccine-eligible adults or adults living with vaccine-eligible individuals have not been previously examined. Assessing trends in provider recommendations for the HPV vaccine and their socio-demographic variations may inform suitable interventions aimed at mitigating disparities in HPV vaccination receipt, which may contribute to accelerating HPV vaccination uptake in the US.

Methods

Data

The data from the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) administered by the National Cancer Institute were analyzed. HINTS is a nationally representative, publicly available, probability survey of adults aged 18 or older in the civilian non-institutionalized population of the US, which collects data on health-related information, knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors, including information about HPV vaccination. Details of survey development, design, and methodology have been published elsewhere and are available online.Citation24 All questionnaire items in HINTS have been tested to be reliable and valid before being administered. HINTS is approved by the NIH Office of Human Subjects Research. Data are publicly available at an open access repository. More information about the validation of the HINTS survey can be found at: https://hints.cancer.gov/faq.aspx. All HINTS questionnaires, data, and reports are available at: http://hints.cancer.gov/hints5.aspx. To determine trends in the prevalence of provider recommendations for the HPV vaccine since the release of the 2012 report of the President’s Cancer Panel, we selected all HINTS surveys where relevant information about provider recommendations was collected. Overall, the HINTS data comprised of 14,119 adults from HINTS 5, cycle 2 (2018, n = 3,527, response rate: 32.9%); HINTS 5, cycle 1 (2017, n = 3,285, response rate: 32.4%); HINTS 4, cycle 4 (2014, n = 3,677, response rate: 34.4%); and HINTS 4, cycle 2 (2012, n = 3,630, response rate: 40.0%).

Measures

Outcome variable

We assessed whether or not providers were recommending HPV vaccination to any vaccine-eligible individual in the family of respondents to the HINTS data using the following questions. “Including yourself, is anyone in your immediate family between the ages of 9 and 27 years old?” If answer to this question was “yes,” a follow-up question was asked: “In the last 12 months, has a doctor or health care professional recommended that you or someone in your immediate family get an HPV shot or vaccine?” The possible responses to our question of interest were “yes,” “no,” and “don’t know.” The respondents to the follow-up question could be either vaccine-eligible adults (age 18–27 y) or parents/guardians or other adult family members of vaccine-eligible children (age ˃27 y).

Independent variables

Because we were primarily interested in comparing trends in recommendations about the HPV vaccine across sex, racial/ethnic, and rurality groups, our main independent variables were sex, race/ethnicity, and residence. Sex was classified as “male” or “female.” Race/Ethnicity was categorized as Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black (NHB), non-Hispanic White (NHW), Asian, and “Other.” Residence was classified along urban/rural categories using 2013 Rural Urban Continuum Codes (RUCCs).Citation25 RUCCs classify metropolitan areas at the county level by population size and non-metropolitan areas by proximity to metropolitan areas and urbanization. Thus, RUCC 1–3 was classified as metropolitan (urban) and RUCC 4–9 as non-metropolitan (rural).

The respondent’s age was also included as an independent variable not only because it may influence the provider recommendation for HPV vaccine but also because it helped distinguish between those responding about their own experience with health-care professional’s recommendation about HPV vaccine and those responding about a family member’s experience. Thus, the study population was classified according to age into two groups: vaccine-eligible individuals (participants ages 18–27 y), who may respond to the study question (provider recommendation for HPV vaccine) based on their own experience, and vaccine-ineligible individuals (respondents aged ˃27 y), who may respond on behalf of a vaccine-eligible member of their immediate family.

Other covariates that could potentially affect provider recommendations for the HPV vaccine, included: most recent routine checkup (within the last 12 months, versus not within the last 12 months) and health insurance (no versus yes).

Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed using SAS (Version 9.4) procedures, which incorporate survey sampling weights to account for the complex sampling design used in HINTS and to provide representative estimates of the US population (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Weighted, prevalence estimates (n, %) with their 95% confidence intervals were used to describe the overall and age-stratified prevalence of provider recommendations about the HPV vaccine at each time-point, and the variations of this prevalence according to sex, race/ethnicity, and residence. For covariates with missing data, a missing data category was created.

We used the average annual percentage change (AAPC), a summary measure of the trend over a fixed time interval, to quantify temporal trends in provider recommendations for the HPV vaccine in the study population from 2012 to 2018.Citation26 The AAPC is computed as follows: changes in trends overtime are estimated using joinpoint regression approach in which data is divided into subsets, where each subset has its own linear trends. The AAPC over any pre-fixed time interval is then calculated using the weighted average of the slope coefficient of the underlying joinpoint regression model and then transforming the weighted average to an annual percent change. AAPC is a valid measure even if the joinpoint model reveals changes in trends over the years. The 95% confidence interval (CI) of the AAPC was also calculated in the regression model, as well as the corresponding p-value. The prevalence of provider recommendations was considered showing an upward trend if the estimated AAPC was positive and the corresponding p-value was <.05. In contrast, this prevalence was considered showing a downward trend if the estimated AAPC was negative and the corresponding p-value was <.05. The trends analysis was performed for the overall study population, as well as stratified by age groups (18–27 and >27), and reported for each sex, race/ethnicity, and residence category of the study population. Weighted 95% confidence intervals were used to compare the rates in the prevalence of an HPV vaccine provider recommendation between the sex, race/ethnicity, and residence categories of the study population. When there was no overlap in the 95% CIs, the difference in the prevalence among categories was considered statistically significant. We used weighted, logistic regression models to determine factors associated with provider recommendations for the HPV vaccine in the study population. All covariates selected for this study were included in the model. Statistical significance was determined using p < .05.

Results

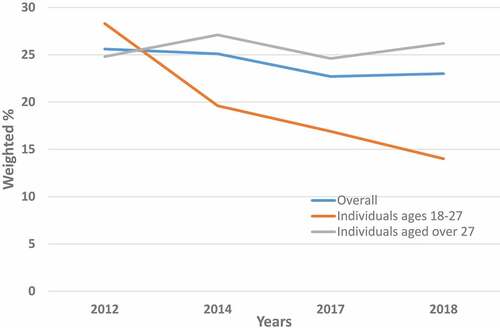

A total of 1,415, 1,476, 1,208 and 1,344 respondents to the HINTS 4, cycle 2; HINTS 4, cycle 4; HINTS 5, cycle 1; and HINTS 5, cycle 2, respectively, were eligible for this study. summarize the rates of provider recommendations for the HPV vaccine in the study population from 2012 to 2018, by age (), sex (), race/ethnicity (), and place of residence (). Additional details including the associated 95% CI are available in Supplementary Tables S1–S4. displays the trends in these rates between 2012 and 2018, overall and according to age categories. The proportion of eligible respondents who reported having received a provider recommendation to any vaccine-eligible individual in their family during the last 12 months decreased from 25.6% to 25.1% in 2012 and 2014, respectively, to 22.7% and 23.0% in 2017 and 2018, respectively (, Supplementary Tables S1A–S4A); this decreasing trend, however, was not statistically significant (AAPC = −4.2%, p = .10) (). A statistically non-significant decreasing trend in the prevalence of provider recommendations was noted in all categories of the study population, except for NHBs, whose prevalence of provider recommendations for the HPV vaccine significantly increased over time (AAPC = 16.4%, p < .001) ().

Table 1. Trends analysis of the prevalence of provider recommendation of HPV vaccine, by sex, race/ethnicity and residence, health information national trends survey (HINTS), 2012–2018

Figure 1. Prevalence of provider recommendation of HPV vaccine in the US adult population, by age, health information national trends survey (HINTS), 2012–2018

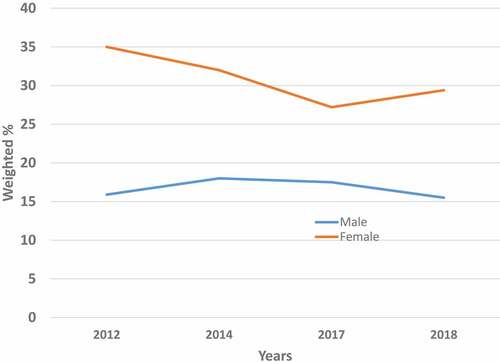

Figure 2. Prevalence of provider recommendation of HPV vaccine in the US adult population, by sex, health information national trends survey (HINTS), 2012–2018

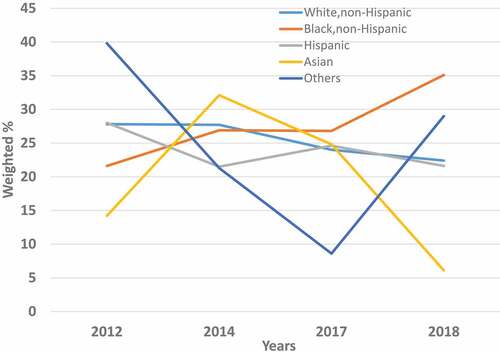

Figure 3. Prevalence of provider recommendation of HPV vaccine in the US adult population, by race/ethnicity, health information national trends survey (HINTS), 2012–2018

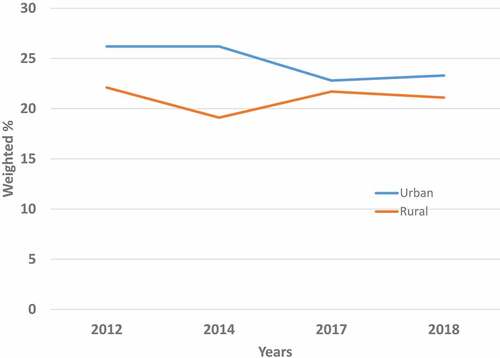

Figure 4. Prevalence of provider recommendation of HPV vaccine in the US adult population, by place of residence, health information national trends survey (HINTS), 2012–2018

Overall, the prevalence of HPV vaccine provider recommendations was roughly twice as high among women as among men (35.0% versus 15.9% in 2012), and this difference remained statistically significant (p < .05) over time (32.0% versus 18.0% in 2014, 27.2% versus 17.5% in 2017, and 29.4% versus 15.5% in 2018). In general, provider recommendations for HPV vaccination did not change over time among men; its prevalence varied from 15.9% in 2012 to 15.5% in 2018 (, Supplementary Tables S1A–S4A). Among women, however, the prevalence of provider recommendations for HPV vaccine slightly decreased from 35.0% in 2012 to 29.4% in 2018, a decline that was statistically non-significant (AAPC = - 6.8%, p = .20) ().

The overall prevalence of provider recommendations about HPV vaccination also varied by the race/ethnicity of respondents. In 2012, this prevalence ranged from a low of 14.2% in Asians to a high of 28.0% in Hispanics (, Supplementary Table S1A), and it ranged from a low of 6.1% in Asians to a high of 35.1% in NHBs in 2018 (, Supplementary Table S4A). Among NHWs, the prevalence of provider recommendations for the HPV vaccine moderately decreased from 27.8% in 2012 to 22.4% in 2018, a non-significant trend that was also observed among Hispanics (from 28.0% in 2012 to 21.6% in 2018). Among NHBs however, a notable and statistically significant (AAPC = 16.4%, p< .001) increase in the prevalence of provider recommendations for the HPV vaccine over time was noted, ranging from 21.6% in 2012 to 35.1% in 2018 (, Supplementary Tables S1A–S4A and ).

With regard to residence, the prevalence of a provider recommendation for the HPV vaccine was slightly, but not significantly (p > .05) higher among urban dwellers compared with rural dwellers (26.2% versus 22.1% in 2012). This urban-rural difference in provider recommendations of HPV vaccination persisted over time, even though it gradually decreased in range (23.3% versus 21.1% in 2018) (, Supplementary Tables S1A–S4A).

The age-stratified trends in the prevalence of provider recommendations for the HPV vaccine are displayed in , Supplementary Tables S1B–S4B and S1C–S4C. In the group of vaccine-eligible individuals (respondents ages 18–27 y) (, Supplementary Tables S1B–S4B), declining trends of provider recommendations for the HPV vaccine over time were noted overall (AAPC = −21.6%, p < .001). Declining trends were also observed among NHWs (AAPC = −30.2%, p < .001) and urban dwellers (AAPC = −21.4%, p < .001) (). Furthermore, these trends were stagnated for the remaining categories of the study population. In the group of vaccine-ineligible individuals (respondents ˃27 y) (, Supplementary Tables S1C–S4C and ), trends were similar to those observed in the overall study population, with a prevalence of provider recommendations for the HPV vaccine increasing significantly over time among NHBs (AAPC = 13.9%, p < .001) and remaining stagnated in the other categories of the study population ().

Logistic regression

displays the factors independently associated with provider recommendations of the HPV vaccine in the overall study population. Sex was the only variable consistently associated with provider recommendations for HPV vaccination across all four HINTS cycles. Specifically, females (adjusted Odds Ratio (aOR): 2.38, 95% CI: 1.55–3.67 in 2012, 1.81 (1.15–2.84) in 2014, 1.74 (1.08–2.80) in 2017, and 1.80 (1.16–2.79) in 2018) were more likely than males to have received a recommendation from a health-care provider to get the HPV vaccine within the last 12 months.

Table 2. Factors associated with provider recommendation of HPV vaccine among US adults who are either vaccine-eligible or are living with vaccine-eligible individuals, HINTS 2012–2018

The other predictive factors of HPV recommendation in the study population varied by HINTS cycle. In 2012 (HINTS 4, cycle 2), NHBs (0.58 (0.34–0.97)) were less likely than NHWs to receive a recommendation from a health-care provider to get the HPV vaccine within the last 12 months, while respondents whose most recent routine checkup was within the last 12 months (2.07 (1.28–3.34)) where twice as likely to have received a provider recommendation as those who did not have a routine checkup visit within the last 12 months. In 2014 (HINTS 4, cycle 4), Hispanics (0.62 (0.39–0.99)) were less likely than HNWs to have received a recommendation from a health-care provider for an HPV vaccination within the last 12 months. In 2018 (HINTS 5, cycle 2), individuals aged between 18 and 27 y (0.49 (0.26–0.92)) were less likely than individuals ˃ 27 y to receive a recommendation from a health-care provider to get the HPV vaccine.

In all four HINTS cycles, health insurance and residence were not associated with increased odds of receiving a provider recommendation about the HPV vaccine within the last 12 months.

Discussion

In this study, we examined the overall, the age stratified, as well as the sex-specific, ethnic/racial, and urban/rural trends in the prevalence of provider recommendations to vaccinate against HPV among vaccine-eligible US adults or those residing with vaccine-eligible individuals. Our results indicate, with the exception of non-Hispanic blacks, that the proportion of individuals in this population who reported having received a provider recommendation for the HPV vaccine during the last 12 months has not increased in the US over time. When we evaluated the trends in the prevalence of provider recommendations for the HPV vaccine in each age category of the study population, we found some important variations across age groups. Declining trends were noted among individuals ages 18–27 y overall, and among NHWs and urban dwellers in this group. This finding is of utmost importance in a setting where HPV vaccination uptake remains suboptimal, failing to meet the Healthy People 2020 goal of 80% coverage, and in a context where a provider’s recommendation for the HPV vaccine is one of the strongest predictors of HPV vaccination.Citation15,Citation27

Previous studies have estimated trends in the prevalence of provider recommendations regarding the HPV vaccine in the US, most of which used the NIS-Teen data.Citation12,Citation13,Citation23 In these reports, an increase in the prevalence of provider recommendations about HPV vaccination over time was consistently observed. The difference with our findings may be explained by the fact that, unlike the NIS-Teen survey that was specifically directed to parents/guardians of 13 to 17 y old adolescents, HINTS data was sent to all individuals aged 18 y or older, including both HPV vaccine-eligible individuals and household members of such individuals. Moreover, the formulation of the question used to report this information in the NIS-Teen survey (i.e., “Has a doctor or other health care professional ever recommended that [TEEN] receive HPV shots?”) refers to “ever” recommendation and did not include a timeframe, unlike the question in the HINTS survey which is specific to the recommendation in the preceding 12 months (i.e., “In the last 12 months, has a doctor or health care professional recommended that you or someone in your immediate family get an HPV shot or vaccine?”), which was used in our study. A possible interpretation of these findings is that US providers may be recommending HPV vaccination to parents/guardians of age-eligible adolescents, but may not be systematically providing HPV recommendation to adults. This could explain, at least in part, the much lower HPV vaccination uptake among vaccine-eligible young adults in the US, compared to their adolescent counterparts. In 2017, HPV vaccination (at least one dose) among females and males 19–26 y who had not received HPV vaccination prior to age 19 y was 8.6% and 5.8%, respectively.Citation28 That same year, 64.5% and 57.1% of girls and boys aged 13–17 y in the US had received at least one dose of HPV vaccination, and 48.6% were up to date on their HPV vaccination schedule.Citation29 This stresses the need for providers to recommend HPV vaccination to their vaccine-eligible adult patients.

Racial disparities and sex-specific differences in provider recommendations of the HPV vaccine for vaccine-eligible household members were also observed in this study. Specifically, we noted increasing trends in the prevalence of provider recommendations for the HPV vaccine among NHBs during the study period (2012 to 2018), which contrasted with the decreasing or rather stagnating trends observed among NHWs. Consistent with our findings, a sharper increase in provider recommendations and HPV vaccination uptake was reported among minority groups (including NHBs) as compared to NHWs.Citation23

We also found that provider recommendations for the HPV vaccine in vaccine-eligible household members were higher among women compared to men. This was confirmed in the logistic regression analysis, where women were consistently more likely than men to have received a recommendation from a health-care provider to get the HPV vaccine during the last 12 months. While this may partly reflect the difference in timing of HPV vaccine recommendations for males and females in the US,Citation9,Citation10 our findings provide further explanation to the sex-specific differences observed in HPV vaccine initiation and completion rates,Citation30,Citation31 including among eligible adults.Citation32 While women are more likely than men to be diagnosed with HPV cancers, the burden of HPV cancers among men is increasing. This trend is driven largely by increases in HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancers over recent decades, particularly among men.Citation4,Citation33 Although the HPV vaccines are not licensed for oropharyngeal cancers, there is a strong body of evidence supporting the positive impact of HPV vaccination on oral HPV acquisition, and by extension, on HPV-associated oral diseases, including oropharyngeal cancers.Citation34,Citation35 Therefore, additional efforts are warranted to strengthen provider recommendations for the HPV vaccine to male age-eligible individuals.

The prevalence of provider recommendations for the HPV vaccine in our study was higher among urban residents compared with rural dwellers, a difference that persisted over time. Consistent with our results, fewer parents living in rural areas in the US report receiving a provider recommendation for the HPV vaccine than those living in metropolitan cities.Citation12 These findings could contribute to the geographic disparities in HPV vaccination coverage in the US, with lower HPV vaccination rates observed in rural areas.Citation12 Thus, emphasis should be made to support providers in rural settings giving recommendations for the HPV vaccine.

Although a leading nation for HPV vaccine introduction and promotion worldwide, the US lags behind many high-income countries with regard to HPV vaccination uptake.Citation36 In light of this, the 2012 report of the President’s Cancer Panel highlighted the need to reduce missed clinical opportunities to recommend and administer the HPV vaccine. This urgent call to action was then renewed by the panel in its 2018 report, which emphasized that provider- and system-level changes hold the greatest potential to reduce these missed clinical opportunities so as to ensure that US residents are optimally protected from HPV-related diseases.Citation19,Citation37 Other major reports, including 2015 and 2018 reports from the National Vaccine Advisory CommitteeCitation38,Citation39 and 2016 reports from the Cancer Moonshot Blue Ribbon PanelCitation40 and Cancer Moonshot Task Force,Citation41 echoed the Presidential Panel’s call for action. Meanwhile, several health professional societies urged their members to strongly recommend HPV vaccination as many providers reported improvements in their communication with patients after receiving information from their scholarly organizations.Citation17,Citation18 This is one of the few instances where many scholarly societies have released a joint statement to firmly recommend a public health intervention to their members. From a provider’s perspective, educational programs aimed at enhancing self-efficacy in promoting HPV vaccination and managing difficult situations, such as vaccine hesitancy, are warranted. Using an innovative approach to increase provider participation in administering effective recommendations for HPV vaccination, improvements in HPV vaccination recommendations by clinicians were noted, as well as HPV vaccine’s uptake.Citation42 The fact that provider recommendation is the strongest predictor of HPV uptake does not imply that stagnating trends observed in this study should necessarily result in stagnating rates of HPV vaccination uptake. Beyond provider recommendations, several factors, such as knowledge about the vaccine, perception of its safety and necessity, parental hesitancy, and health insurance coverage play key roles in HPV vaccination uptake.Citation43 In the US, the overall HPV vaccine uptake is steadily increasing over time in the eligible population, although this increase varies by sex, race/ethnicity, and geographic region.Citation12 Nonetheless, a strong correlation between provider recommendations for a health behavior and its influence on the uptake of this behavior is well documented in other areas of cancer prevention, such as smoking cessation.Citation44 Therefore, provider recommendations for the HPV vaccine will likely remain an important driver of HPV vaccination uptake.

Strengths and limitations

Our study has many strengths. First, we used a representative sample of the US adult population. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study examining trends in provider recommendations about the HPV vaccine in the US population of adults who are either vaccine eligible or residing with vaccine-eligible individuals, before the recent Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommendation of shared clinical decision-making for HPV vaccination for adults aged 27 through 45. Second, our study outcome was time specific (within the last 12 months preceding the survey), which may have contributed to reducing the risk of recall bias, unlike studies based on NIS-Teen data where there was no timeframe in the formulation of the question. However, this study was limited by the inability to correlate provider recommendations to actual HPV vaccine uptake in the target population. Also, the outcome measure was based on the recall of the participant’s experience with their provider’s recommendation in the past year, which could be subject to a level of recall bias. Since the information about having received the HPV vaccine was not available, we could not exclude from our study population respondents who have previously been vaccinated for HPV. Considering the two-part nature of the question used to define the outcome variable in this study, it was not possible to distinguish between individuals who responded based on their own experience with the HPV vaccine and those who responded on behalf of their family members. To reduce the impact of this limitation on our findings, we divided the study population into two age groups: vaccine eligible individuals (ages 18–27 y), and vaccine ineligible adults (aged ˃27 y) residing with vaccine eligible individuals. Further, HINTS data could be affected by biases inherent to cross-sectional surveys, such as low-response and social desirability biases. However, significant efforts were made to reduce bias potential through modality coverage and sampling.Citation45

Conclusion

Our results suggest variations of trends in provider recommendations for the HPV vaccine in the US adult population according to age, as well as sex-specific, regional and ethnic disparities in this key intervention. To accelerate HPV vaccination uptake in the US, in addition to increasing awareness about the HPV, HPV vaccine, and its safety, urgent actions are needed to enhance provider participation in the promotion of HPV vaccination, especially among males, urban population, and NHWs.

Access to data and data analysis

Dr. Shete has full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for their integrity, as well as for data analysis accuracy.

Author contributions

Concept and Study Design: Fokom Domgue, Shete

Data Analysis: Yu

Interpretation of the data: Fokom Domgue, Shete

Initial Draft: Fokom Domgue

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Fokom Domgue, Shete

Obtained Funding and Study Supervision: Shete

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Role of funder/sponsor statement

The funders had no involvement in design and conduct of the study; analysis and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Supplemental Material

Download ()Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website at https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2021.1917235.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Satterwhite CL, Torrone E, Meites E, Dunne, EF, Mahajan, R, Ocfemia, MCB, Su, J, Xu, F, Weinstock, H. Sexually transmitted infections among US women and men: prevalence and incidence estimates, 2008. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40:187–93. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318286bb53.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Genital HPV infection - fact sheet. [accessed 2019 Sep 4]. https://www.cdc.gov/std/hpv/stdfact-hpv.htm.

- Senkomago V, Henley SJ, Thomas CC, Mix, JM, Markowitz, LE, Saraiya, M. Human papillomavirus-attributable cancers - United States, 2012–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:724–28. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6833a3.

- Van Dyne EA, Henley SJ, Saraiya M, Thomas CC, Markowitz LE, Benard VB. Trends in human papillomavirus-associated - cancers United States, 1999–2015. MMWR-Morbidity Mortality Weekly Rep. 2018;67:918–24. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6733a2.

- Kang YJ, Smith M, Canfell K. Anal cancer in high-income countries: increasing burden of disease. Plos One. 2018;13. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0205105.

- Xu L, Dahlstrom KR, Lairson DR, Sturgis EM. Projected oropharyngeal carcinoma incidence among middle-aged US men. Head Neck. 2019;41:3226–34. doi:10.1002/hed.25810.

- Smith BD, Smith GL, Hurria A, Hortobagyi, GN, Buchholz, TA. Future of cancer incidence in the United States: burdens upon an aging, changing nation. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2758–65. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8983.

- Arbyn M, Xu L. Efficacy and safety of prophylactic HPV vaccines. A Cochrane review of randomized trials. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2018;17:1085–91. doi:10.1080/14760584.2018.1548282.

- Markowitz LE, Dunne EF, Saraiya M, Lawson, HW, Chesson, H, Unger, ER. Quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2007;56:1–24.

- Centers for Disease C, Prevention. Recommendations on the use of quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine in males–Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2011;60:1705–08.

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. 2020 Healthy people goals. Immunization and infectious diseases. [accessed 2019 Sep 4]. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/immunization-and-infectious-diseases/objectives.

- Walker TY, Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, Markowitz, LE, Williams, CL, Fredua, B, Singleton, JA, Stokley, S. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years - United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:718–23. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6833a2.

- Lu PJ, Yankey D, Fredua B, O’Halloran, AC, Williams, C, Markowitz, LE, Elam-Evans, LD. Association of provider recommendation and human papillomavirus vaccination initiation among male adolescents aged 13–17 years-United States. J Pediatr. 2019;206:33-+. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.10.034.

- Holman DM, Benard V, Roland KB, Watson, M, Liddon, N, Stokley, S. Barriers to human papillomavirus vaccination among US adolescents a systematic review of the literature. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168:76–82. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2752.

- Ylitalo KR, Lee H, Mehta NK. Health care provider recommendation, human papillomavirus vaccination, and race/ethnicity in the US national immunization survey. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:164–69. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300600.

- Accelerating HPV vaccine uptake. Urgency for action to prevent cancer. A report to the President of the United States from the President’s Cancer Panel. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute; 2014. http://deainfo.nci.nih.gov/advisory/pcp/annualReports/HPV/index.htm.

- American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, American College of Physicians, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Immunization Action Coalition. Letter to: colleagues. 2014 [accessed 2019 Sep 4]. http://www.immunize.org/letter/recommend_hpv_vaccination.pdf.

- Hswen Y, Gilkey MB, Rimer BK, Brewer, NT. Improving physician recommendations for human papillomavirus vaccination: the role of professional organizations. Sex Transm Dis. 2017;44:43–48. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000543.

- Razfar A, Mundi J, Grogan T, Lee, S, Elashoff, D, Abemayor, E, St. John, M. IMRT for head and neck cancer: cost implications. Am J Otolaryngol. 2016;37:479–83. doi:10.1016/j.amjoto.2015.02.017.

- Thompson EL, Rosen BL, Vamos CA, Kadono, M, Daley, EM. Human papillomavirus vaccination: what are the reasons for nonvaccination among US adolescents? J Adolesc Health. 2017;61:288–93. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.05.015.

- Hanson KE, Koch B, Bonner K, McRee, A-L, Basta, NE. National trends in parental human papillomavirus vaccination intentions and reasons for hesitancy, 2010–2015. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67:1018–26. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy232.

- Burdette AM, Gordon-Jokinen H, Hill TD. Social determinants of HPV vaccination delay rationales: evidence from the 2011 national immunization survey-Teen. Prev Med Rep. 2014;1:21–26. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2014.09.003.

- Burdette AM, Webb NS, Hill TD, Jokinen-Gordon, H. Race-specific trends in HPV vaccinations and provider recommendations: persistent disparities or social progress? Public Health. 2017;142:167–176. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2016.07.009.

- Fokom-Domgue J, Vassilakos P, Petignat P. Is screen-and-treat approach suited for screening and management of precancerous cervical lesions in Sub-Saharan Africa? Prev Med. 2014;65:138–40. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.05.014.

- Westmaas JL, Alcaraz KI, Berg CJ, Stein KD. Prevalence and correlates of smoking and cessation-related behavior among survivors of ten cancers: findings from a nationwide survey nine years after diagnosis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23:1783–92. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0046.

- Clegg LX, Hankey BF, Tiwari R, Feuer, EJ, Edwards, BK. Estimating average annual per cent change in trend analysis. Stat Med. 2009;28:3670–82. doi:10.1002/sim.3733.

- Mohammed KA, Geneus CJ, Osazuwa-Peters N, Adjei Boakye, E, Tobo, BB, Burroughs, TE. Disparities in provider recommendation of human papillomavirus vaccination for US adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59:592–98. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.005.

- Diseases. CNCfIaR: vaccination coverage among adults in the United States. National health interview survey, 2017. 2018 [accessed2020 Feb 14]. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/coverage/adultvaxview/pubs-resources/NHIS-2017.html.

- Walker TY, Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, Markowitz, LE, Williams, CL, Mbaeyi, SA, Fredua, B, Stokley, S. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years - United States, 2017 (vol 67, pg 909, 2018). MMWR-Morbidity Mortality Weekly Rep. 2018;67:1164–1164. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6733a1.

- Agawu A, Buttenheim AM, Taylor L, Song, L, Fiks, AG, Feemster, KA. Sociodemographic differences in human papillomavirus vaccine initiation by adolescent males. J Adolesc Health. 2015;57:506–14. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.07.002.

- Rahman M, McGrath CJ, Hirth JM, Berenson, AB. Age at HPV vaccine initiation and completion among US adolescent girls: trend from 2008 to 2012. Vaccine. 2015;33:585–87. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.12.021. 5

- Boakye EA, Lew D, Muthukrishnan M, Tobo, BB, Rohde, RL, Varvares, MA, Osazuwa-Peters, N. Correlates of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination initiation and completion among 18–26 year olds in the United States. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14:2016–24. doi:10.1080/21645515.2018.1467203.

- Gillison ML, Chaturvedi AK, Anderson WF, Fakhry C. Epidemiology of human papillomavirus-positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3235–42. doi:10.1200/JCO.2015.61.6995.

- Schlecht NF, Masika M, Diaz A, Nucci-Sack, A, Salandy, A, Pickering, S, Strickler, HD, Shankar, V, Burk, RD. Risk of oral human papillomavirus infection among sexually active female adolescents receiving the quadrivalent vaccine. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.14031. e1914031

- Chaturvedi AK, Graubard BI, Broutian T, Pickard, RKL, Tong, Z-Y, Xiao, W, Kahle, L, Gillison, M L. Effect of prophylactic human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination on oral HPV infections among young adults in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:262-+. doi:10.1200/JCO.2017.75.0141.

- Brotherton JML, Bloem PN. Population-based HPV vaccination programmes are safe and effective: 2017 update and the impetus for achieving better global coverage. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;47:42–58. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2017.08.010.

- Brewer NT, Chapman GB, Rothman AJ, Leask J, Kempe A. Increasing vaccination: putting psychological science into action. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2017;18:149–207. doi:10.1177/1529100618760521.

- National Vaccine Advisory Committee. Overcoming barriers to low HPV vaccine uptake in the United States: recommendations from the National Vaccine Advisory Committee. Washington (DC): NVAC; 2015 Jun 9. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/nvpo/nvac/reports/nvac-hpv.pdf/.

- National Vaccine Advisory Committee. Strengthening the effectiveness of national, state, and local efforts to improve HPV vaccination coverage in the United States: recommendations of the National Vaccine Advisory Committee. Washington (DC): NVAC; 2018 Jun 25. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/2018_nvac_hpv-report_final_remediated.pdf.

- Cancer Moonshot Blue Ribbon Panel. Cancer Moonshot Blue Ribbon Panel report 2016. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute; 2016 Oct 17. https://www.cancer.gov/research/key-initiatives/moonshot-cancer-initiative/blue-ribbon-panel/

- Cancer Moonshot Task Force. Report of the Cancer Moonshot Task Force. Washington (DC): The White House; 2016 Oct 17. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/docs/final_cancer/moonshot_task_force_report_1.pdf.

- Henninger ML, McMullen CK, Firemark AJ, Naleway AL, Henrikson NB, Turcotte JA. User-centered design for developing interventions to improve clinician recommendation of human papillomavirus vaccination. Permanente J. 2017;21:16–191. doi:10.7812/TPP/16-191.

- Newman PA, Logie CH, Lacombe-Duncan A, Baiden P, Tepjan S, Rubincam C, Doukas N, Asey F. Parents’ uptake of human papillomavirus vaccines for their children: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ Open. 2018;8. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019206.

- Park ER, Gareen IF, Japuntich S. Primary care provider-delivered smoking cessation interventions and smoking cessation among participants in the national lung screening trial (vol 175, pg 1509, 2015). JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:1587+. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2391.

- Cantor CK C-MS, Davis T, Dipko S, Sigman R. Health information national trends survey (HINTS) 2007: final report. Rockville (MD): Westat; 2009.