ABSTRACT

Achieving and maintaining high-level immunization coverage is the priority of the health-care delivery system. However, any delay in receiving the vaccine leaves youngsters inadequately protected. Timely vaccination has scarcely been reported and given little attention in developing nations like Ethiopia, which hinders effective interventions. Therefore, this study aimed to assess age-appropriate vaccination practice and associated factors among mothers of children aged less than one year in the pastoral community. A community-based cross-sectional study has conducted among 340 mothers/caregivers of children aged less than one year in Samara-logia city administration. A systematic random sampling technique was employed to identify and enroll mothers-child paired. The logistic regression analysis had done to identify the factors associated with age-appropriate vaccination practice. The statistical association had measured, and a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. In this study, a total of 331 mothers/caregivers–child pairs participated with a response rate of 97.3%. The age-appropriate vaccination practice was 43.7% (95% CI, 38%, 49.5%). Mothers who had higher educational level (Adjusted odds ratio (AOR)) = AOR = 2.89, 95% CI (1.14, 7.3), antenatal care follow-up (AOR = 2.1, 95% CI (1.04, 4.1)), and had good knowledge on vaccination (AOR = 3.1, 95% CI (1.4, 6.78)) were associated with increased odds of age-appropriate vaccination practice.

Introduction

Vaccination is one of the foremost cost-efficient health interventions, through that many serious childhood diseases were successfully prevented.Citation1 The beginning of an expanded program on immunization in 1974, and the widespread use of vaccines has considerably reduced vaccine-preventable morbidity and mortality.Citation2,Citation3

Despite improvements, immunization is an unfinished agenda in many developing countries, including Ethiopia. About 1.5 million children were estimated to have died, and more than 70% of them live in ten African and Asian countries.Citation4,Citation5 In sub-Saharan Africa, 4.4 million children died yearly due to transmittable diseases that could be avoidable by immunization.Citation6 In Ethiopia, frequent measles outbreaks, high child morbidity, and mortality rates were among the consequences of low immunization coverage, and immunization currently averts an estimated 2 to 3 million deaths every year.Citation7,Citation8

Countries including Ethiopia were planned to succeed vaccination coverage of ≥90% across the nation and ≥80% in each district by 2020.Citation8 However, findings indicate that low access to services, inadequate awareness of vaccination, missing opportunities, inconvenient vaccination schedules, distance from health facilities, and worry of vaccine side effects were the main factors conducive to low vaccination coverage.Citation2,Citation9

In Ethiopia, the routine schedule recommends that infants should receive the following vaccine schedule: one dose of Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) at birth or as soon as possible, three doses of diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus (DPT) with hepatitis B (HepB) and Hemophilus influenza type b (Hib) (DPT-HepB-Hib), three doses of pneumococcal vaccine (PCV), and three doses of oral polio vaccine (OPV) at 6, 10, and 14 weeks. Moreover, two-dose of the Rota vaccine (R) at 6, 10 weeks, and one dose of measles vaccine at nine months.Citation8

Ethiopia has shown encouraging enhancements in the accessibility and provision of primary health-care services, particularly since the beginning of the health extension program.Citation10 Besides, the country implemented the Women’s Development Army (WDA) initiative.Citation11 Despite this intervention, the age-appropriate vaccination coverage remained low and challenging.Citation12 In Ethiopia, the percentage of children age 12–23 months who received all vaccinations increased from 14% in 2000 to 43% in 2019.Citation12 However, according to the 2016 Ethiopian demographic health survey in the Afar region, it was 19.8%. Vaccine-preventable diseases are responsible for 16% of under-five mortality in Ethiopia.Citation13

Achieving and maintaining high-level vaccination coverage is the priority of health-care delivery systems. However, any delay in receiving regular vaccines leaves children inadequately protected and in danger of infectious diseases. The timeliness of vaccinations at the earliest applicable age is a public health goal. However, this information is commonly lacking as coverage is the mainly used method. Besides, it compromises herd immunity with a consequent potential risk of outbreaks.Citation14,Citation15 Therefore, this study aimed to assess age-appropriate vaccination practice and associated factors among mothers of children aged less than one year in the pastoral community of the Afar region, Ethiopia.

Methods

Study design and participants

A community-based cross-sectional study has conducted among 331 mothers/caregivers with children aged <12 months in Samara-logia city administration during January 2020. The location of city administration is at 580-kilometer northeast of Addis Ababa (the capital of Ethiopia). The average altitude of the town is 420 meters above sea level. The annual rainfall is below 200 millimeters, and the average temperature is 35 degrees centigrade. According to the Afar National Regional State Health Bureau Report, the city administration have populations of 59,255. The women in the reproductive age group were about 14,579, with 7314 were children aged less than five years, and 850 were children aged <12 months. The city administration has 13 ketenas (the lowest administrative units). There are also one primary hospital, two government health centers, and 15 private clinics.

Sample size determination and sampling techniques

The sample size was determined using single population proportion formula with the assumption: 5% type one error, 95% confidence interval (CI), P = 15.2% fully vaccinated children in the Afar region.Citation16 Then, we added 10% to compensate for the nonresponse, and the final sample size became 340.

n = (Zα/2)2 p (1-p)

d2

Where: n = required sample size, Zα/2 = critical value for normal distribution at 95% confidence level (1.96), p = proportion of fully vaccinated children in Afar region, d = 0.04 (4% margin of error).

Out of thirteen ketenas: Eight ketanas in logia city and five ketenas in semera city, six ketenas were selected (four ketenas from Logia city and two from Semera city) using the lottery method. The calculated sample size had proportionally allocated to randomly selected ketenas. There was a total of 850 children aged <12 months in the randomly selected ketenas (i.e., Ketena-1 = 78, Ketena-2 = 257, Ketena-3 = 95 and Ketena-4 = 145, ktena-5 = 155, and ketene-7 = 120). A systematic random sampling technique was employed to enroll the study participants. Accordingly, every three participants were selected using a systematic random sampling technique till the required sample size.

Study variables

Dependent variable

In this study, the dependent variable was ‘age-appropriate vaccination practice’ among mothers/caregivers of children aged <12 months. Age-appropriate vaccination is mothers/caregivers who vaccinated their children timely within the WHO recommended period and national EPI schedule. Vaccination of children on the recommended was coded as ‘1’ and coded as ‘0’ if the child received the vaccine earlier than the recommended age, or delay for regression analysis.

Independent variables: The independent variables were socio-demographic characteristics (sex, parent education, parent occupation, family size, number of children, and birth order), knowledge on vaccination, and maternal health services characteristics (antenatal care service, post-natal care, tetanus toxoid vaccination status, place of delivery, knowledge status (good or Poor)).

Operational definitions

Fully vaccinated: If he/she had received all of the doses of the following vaccines: BCG, OPV0, DTP-HepB1-Hib1, OPV1, Rota1, PCV1, DTP-HepB1-Hib2, OPV2, Rota2, PCV2, DTP -HepB1-Hib3, OPV3, PCV 3, and measles.Citation17

Age-appropriate vaccination practice: If infants had received all doses of vaccine timely according to the expanded program immunization (EPI) schedule.Citation17

Drop out: When an infant missed any one of the vaccines does.Citation17

Knowledge: Is defined as when study participant’s knowledge on vaccines about previous information on the vaccine, source of information, number of vaccine-preventable diseases, the right time to start vaccination, number of sessions to complete vaccination, and age to complete vaccination.

Good knowledge: Is defined as scoring 75%-100% from the knowledge measuring question and coded as 1 for regression analysis.

Poor knowledge: Is defined as scoring <75% from the measuring questions and coded as 0 for regression analysis.

Data collection tools and techniques

Data were collected using a pretested, structured, and interviewer-administered questionnaire adapted from literature reviews and the 2016 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (see ). The questionnaire consists of socio-demographic, knowledge on vaccination and maternal health services characteristics, and vaccination status. The adapted questionnaire was modified and contextualized to fit the local circumstances and the research objective.

The questionnaire was prepared first in English and translated into Amharic and back to English to check for consistency. The Amharic version of the questionnaire has used to collect the data. The tool pretested on 5% of mothers having children aged <12 months other than selected kebeles in Dubti district. Information about children’s vaccination status had been collected from children’s vaccination cards. For children without a vaccination card, the mothers/caregivers were asked to recall. A scare on vaccination sites was observed. The data was collected by five-diploma nurses. The data collectors and the supervisors (two diploma nurses) were trained for two days by the researcher on the study instrument, how to approach study participants, and data collection procedure.

Data quality control methods

Diploma nurses who can speak the local language had been recruited as data collectors. Data collectors and supervisors trained on the study objective, the questionnaires, how to approach study participants and consent form to ensure quality data. The questionnaire was pretested on 5% of mothers/caregivers with children aged <one year other than selected kebeles in Dubti district. The pretest was done to ensure clarity, wordings, logical sequence, skip patterns of the questions and the amendment made accordingly. The supervisors checked the day-to-day activities of data collectors regarding the completion of questionnaires and clarity of responses.

Data management and analysis

The data were checked for completeness, coded, recorded, and entered into Epi data version 3.1 software and exported to statistical package for social science (SPSS) version 20 for analysis. The descriptive analysis was done, and the results were presented using texts, frequency tables, figures, and mean with standard deviation (±SD).

A binary logistic regression analysis was done to assess the association between the independent variables with the dependent variable. Socio-demographic characteristics (sex, parent education, parent occupation, family size, number of children, and birth order), knowledge on vaccination and maternal health services characteristics (antenatal care service, post-natal care, tetanus toxoid vaccination status, place of delivery, knowledge status) were the independent variables included in the binary analysis. Thus, independent variables with a p-value less than 0.25 considered in the final model. Correlation between independent variables was assessed, but we did not find any correlation. The model fitness also checked using the Hosmer-Lemeshow model fitness test. Finally, multivariable logistic regression analysis was done to control potential confounders and identify the factors associated with age-appropriate vaccination practice. A statistical significance level was declared at a p-value of less than 0.05.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Ethical Review Committee (ERC) of Samara University. An official letter written from Samara University to the samara-logia city administration Office. Then permission and support letter was written to each selected ketena. The participants enrolled in the study were informed about the study objectives, expected outcomes, benefits, and the risks associated with it. The verbal consent was taken from the participants before the interview. Confidentiality of responses was maintained during the study period.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics

In this study, a total of 331 mothers/caregivers-child pairs were included in the study with a response rate of 97.3%. The mean age of mothers was 33.5 (with a standard deviation of ±8.02) years, and about 126 (38.1%) of the mothers were in the age group of 20–34 years. In this study, 278 (84%) mothers/caregivers were Muslim, and 220 (66.5%) mothers were Afar in the Ethnic group. In this study, 177 (53.5%) children were male. The mean age of children was 6.71 (±2.92) months, and about 235 (71%) children were in the age group of 6–11 months ().

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of mothers/caregivers and children aged less than one year in Samara-logia city administration, Afar region, Northeast Ethiopia, January 2020

Knowledge on vaccination and maternal health services characteristic

In this study, 331 (100%) mothers/caregivers had heard about vaccination. About 272 (82.2%) mothers/caregivers know the existence of 10 available vaccines, 185 (5.9) five sessions for full vaccination, 294 (8.8%) complete immunization at nine months of age, and 267 (0.5%) had good knowledge on vaccinations. In this study, 233 (0.4%) mothers/caregivers had antenatal care follow-up (ANC), 36 (15.4%) had four and above ANC visits, and 135 (40.8%) delivered at health facilities. In this study, 164 (49.5%) mothers/caregivers have heard the source of information on vaccination programs from health facilities, and 159 (48%) from television ().

Table 2. Knowledge on vaccination and maternal health services utilization characteristics of mothers/caregivers with children aged less than one year in Samara-logia city administration, Afar region, Northeast Ethiopia, January 2020

Vaccination coverage

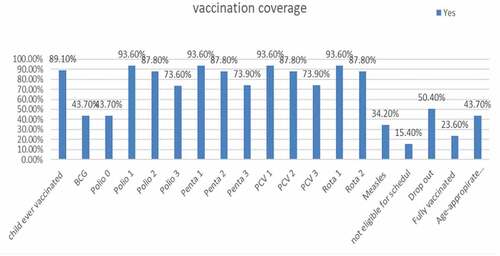

In this study, 295 (89.1%) children ever vaccinated, 158 (53.6%) had vaccination card, 129 (43.7%) age-appropriate vaccination, 101 (34.2%), vaccinated for measles, and 78 (23.6%) were fully vaccinated ().

Figure 1. Percentage of vaccination coverage among children aged less than one year in Samara-logia city administration, Afar region, Northeast Ethiopia, January 2020

Factors associated with age-appropriate vaccination practice

Binary logistic regression analysis showed that maternal educational level, antenatal care (ANC), post-natal care, and good knowledge on vaccination were statistically associated with age-appropriate vaccination practice at p-value < 0.05 (). In multivariable logistic regression analysis, maternal education, antenatal care (ANC), and good knowledge on vaccinations were statistically associated with age-appropriate vaccination practice at p < .05 ().

Table 3. Binary and multivariable logistic regression analysis showing factors associated age-appropriate vaccination practice among mothers/caregivers with children aged less than one year in Samara-logia city administration, Afar region, northeast Ethiopia, January 2020

In this study, the odds of age-appropriate vaccination practice among mothers/caregivers who had higher educational levels were 2.89 times more than mothers/caregivers who had no education (AOR = 2.89, 95% CI (1.14, 7.3)). The mother who had antenatal care follow-up was 2.1 times more likely to age-appropriate vaccination practice than their counterpart (AOR = 2.1, 95% CI (1.04, 4.1)). The odds of age-appropriate vaccination practice among mothers/caregivers who had good knowledge of vaccination were three-fold higher compared to their counterparts (AOR = 3.1, 95% CI (1.4, 6.78)) ().

Discussion

This study aimed to assess age-appropriate vaccination practice and associated factors among mothers/caregivers of children aged less than one year. Based on this, the prevalence of age-appropriate vaccination practice was 43.7% (95% CI, 38%, 49.5%). Moreover, mother/caregivers who had higher education, good knowledge on vaccination, and antenatal care (ANC) follow-up were predictors of age-appropriate vaccination practice.

Though the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Ethiopian expanded program on immunization (EPI) recommend infants should receive the vaccine on age-appropriate basis,Citation8,Citation18 this study showed that 43.7% [95% CI: 38.3%, 49.5%] children less than 1 year were age-appropriate vaccination. This study was similar to studies conducted in Uganda, 45.6%,Citation19 and nearly the study done in China range from 43.72% to 59.25% for different types of vaccine.Citation20 In this study, the age-appropriate vaccination practice was lower than studies done in Tanzania 82.7% to 88.5%,Citation21 Saudi Arabia 73%,Citation22 Ghana 87.3%,Citation23 Cameron 73.3%,Citation24 in Senegal 78.4%,Citation24 Kenya 71–91%,Citation25 Senegal 78.4%,Citation26 and South Africa 58% to 88%.Citation27 The reason might be due to less attention for age-appropriate vaccination and the lack of timeliness indicators in the Ethiopian vaccination programs. Moreover, most of the studies were facility-based, and it could be a good opportunity for infants to vaccinate BCG and OPV0 vaccine on age-appropriate.

However, age-appropriate vaccination practice was higher than studies done in India 29.5%,Citation28 Gambia 36.7%,Citation29 and Kenya 30.3%.Citation26 The reason might be the women’s development army and deployed health extension workers at the community level in Ethiopia might increase awareness creation on vaccination programs through the house to house visits.Citation10,Citation11

In this study, the odds of age-appropriate vaccination practice among mothers/caregivers who had higher educational levels were 2.89 times more than mothers/caregivers who had no education. This study was consistent with studies done in Tanzania,Citation21 Cameron,Citation24 Malawi,Citation30 Saudi Arabia,Citation22 and China.Citation20 The reason might be education could increase communication and have a positive influence on childhood immunization. Several studies show that maternal educational level can improve vaccination of children.Citation31,Citation32

The mothers/caregivers who had antenatal care follow-up were 2.1 times more likely to age-appropriate vaccination practice than their counterparts. This study was in line with studies done in Tanzania,Citation21 Sinana District, Southeast Ethiopia,Citation33 and Ambo woreda, Central Ethiopia.Citation34 The reason might be mothers/caregivers who had attended antenatal care follow-up services can receive counseling services on the vaccination programs.

Furthermore, the odds of age-appropriate vaccination practice among mothers/caregivers who had good knowledge of vaccination were three-fold higher than their counterparts. Similar findings had reported in northeast Ethiopia,Citation35 Tigray Region, Northern Ethiopia,Citation36 Sinana District, Southeast Ethiopia,Citation33 India,Citation28 and Pakistan.Citation37 The reason might be the mothers/caregivers having prior knowledge on the importance of vaccines helps mothers/caregiver to vaccinate their children on age-appropriate vaccination based on the National recommended schedule. It had noted that there was an increased age-appropriate vaccination practice among mothers exposed to media.Citation38,Citation39 Therefore, to improve the age-appropriate vaccination practice increasing knowledge of mothers/caregivers on vaccination programs, access to education for mothers/caregivers, and improving maternal health services utilization like antenatal care follow-up services is mandatory.

Limitation: Variables such as illness and unavailability of both parents could not address in the study though these variables are significant. The fact that the urban vaccination centers are static does not rule out the difficulty in accessing them. However, the inability to reach vaccination was purposefully left as the study had done in urban city administration where there are one primary hospital and two government health centers providing static routine vaccination programs. There might be recall bias on age-appropriate vaccination. Moreover, cause and effect relation had not been addressed because of the cross-sectional study design.

Conclusion

This study showed that four of nine children aged less than one year were age-appropriate vaccination, and it is low compared to WHO and national EPI recommendations. Maternal education, antenatal care (ANC), and good knowledge of vaccination were predictors of age-appropriate vaccinations. Therefore, increasing knowledge of mothers/caregivers on vaccination programs, access to education for mothers/caregivers, and improving maternal health services utilization is significant. Besides, age-appropriate vaccination indicator needs addressing in the health-care delivery and information management system.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Contributor statement

SA has conceived the study, carried out the overall design, execution the study, performed data collection and statistical analysis. EW and BM revised the study design, data collection techniques and helped the statistical analysis. EW has drafted the manuscript, and all authors read and finally approved this manuscript for submission.

References

- Angela G, Zulfiqar B, Lulu B, Aly G, Dennis J, Anwar H. Pediatric disease burden and vaccination recommendations: understanding local differences [systematic review]. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;30:1019–29.

- Odusanya OO, Alufohai EF, Meurice FP, Ahonkhai VI. Determinants of vaccination coverage in rural Nigeria. BMC Public Health. 2008;8(1):1–8. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-8-381.

- Organization WH. Vaccines against influenza WHO position paper—November 2012. Weekly Epidemiological Record= Relevé épidémiologique hebdomadaire. 2012;87(47):461–76.

- Ababa A Government of Ethiopia. Ministry of Health; 2007.

- Ryman TK, Dietz V, Cairns KL. Too little but not too late: results of a literature review to improve routine immunization programs in developing countries. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8(1):1–11. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-8-134.

- Atkinson W. Epidemiology and prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases. Department of Health & Human Services, Centers for Disease Control, USA; 2006.

- Belete H, Kidane T, Bisrat F, Molla M, Mounier-Jack S, Kitaw Y. Routine immunization in Ethiopia. Ethiopian J Health Dev. 2015;29:1.

- FMoH E Ethiopia national expanded programme on immunization comprehensive multi-year plan 2016-2020. FMOH; 2015.

- Antai D. Migration and child immunization in Nigeria: individual-and community-level contexts. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(1):1–12. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-116.

- Okwaraji YB, Hill Z, Defar A, Berhanu D, Wolassa D, Persson LÅ, Gonfa G, Schellenberg JA. Implementation of the ‘Optimising the Health Extension Program’Intervention in Ethiopia: a Process Evaluation Using Mixed Methods. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(16):5803. doi:10.3390/ijerph17165803.

- Maes K, Closser S, Vorel E, Tesfaye Y. Using community health workers: discipline and hierarchy in Ethiopia’s women’s development army. Ann Anthropol Pra. 2015;39(1):42–57. doi:10.1111/napa.12064.

- Ethiopia CSAo. Ethiopia mini demographic and health survey; 2019.

- Berhane Y. Universal childhood immunization: a realistic yet not achieved goal. Ethiopian J Health Dev. 2008;22:2.

- Kurosky SK, Davis KL, Krishnarajah G. Completion and compliance of childhood vaccinations in the United States. Vaccine. 2016;34(3):387–94. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.11.011.

- Lernout T, Theeten H, Hens N, Braeckman T, Roelants M, Hoppenbrouwers K, Van Damme P. Timeliness of infant vaccination and factors related with delay in Flanders, Belgium. Vaccine. 2014;32(2):284–89. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.10.084.

- Agency CS. Ethiopian demographic health survy; 2016.

- Who U. World Bank. State of the world’s vaccines and immunization. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2009. p. 130–45.

- Organization WH. Immunization surveillance, assessment and monitoring. 2013.

- Babirye JN, Engebretsen IM, Makumbi F, Fadnes LT, Wamani H, Tylleskar T, Nuwaha F. Timeliness of childhood vaccinations in Kampala Uganda: a community-based cross-sectional study. PloS One. 2012;7(4):e35432. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0035432.

- Hu Y, Chen Y, Guo J, Tang X, Shen L. Completeness and timeliness of vaccination and determinants for low and late uptake among young children in eastern China. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014;10(5):1408–15. doi:10.4161/hv.28054.

- Nadella P, Smith ER, Muhihi A, Noor RA, Masanja H, Fawzi WW, Sudfeld CR. Determinants of delayed or incomplete diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccination in parallel urban and rural birth cohorts of 30,956 infants in Tanzania. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):1–11. doi:10.1186/s12879-019-3828-3.

- Alrowaili GZ, Dar UF, Bandy AH. May we improve vaccine timeliness among children? A cross sectional survey in northern Saudi Arabia. J Family Community Med. 2019;26:113.

- Laryea DO, Parbie EA, Frimpong E. Timeliness of childhood vaccine uptake among children attending a tertiary health service facility-based immunisation clinic in Ghana. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):1–5. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-90.

- Chiabi A, Nguefack FD, Njapndounke F, Kobela M, Kenfack K, Nguefack S, Mah E, Nguefack-Tsague G, Angwafo F. Vaccination of infants aged 0 to 11 months at the Yaounde Gynaeco-obstetric and pediatric hospital in Cameroon: how complete and how timely? BMC Pediatr. 2017;17(1):1–7. doi:10.1186/s12887-017-0954-1.

- Gibson DG, Ochieng B, Kagucia EW, Obor D, Odhiambo F, O’Brien KL, Feikin DR. Individual level determinants for not receiving immunization, receiving immunization with delay, and being severely underimmunized among rural western Kenyan children. Vaccine. 2015;33(48):6778–85. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.10.021.

- Delrieu I, Gessner BD, Baril L, Bahmanyar ER. From current vaccine recommendations to everyday practices: an analysis in five sub-Saharan African countries. Vaccine. 2015;33(51):7290–98. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.10.107.

- Fadnes LT, Jackson D, Engebretsen IM, Zembe W, Sanders D, Sommerfelt H, Tylleskär T. Vaccination coverage and timeliness in three South African areas: a prospective study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):1–12. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-11-404.

- Sood RK, Sood A, Bharti OK, Ramachandran V, Phull A. High immunization coverage but delayed immunization reflects gaps in health management information system (HMIS) in district Kangra, Himachal Pradesh, India—an immunization evaluation. World J Vacc. 2015;5(2):69. doi:10.4236/wjv.2015.52009.

- Odutola A, Afolabi MO, Ogundare EO, Lowe-Jallow YN, Worwui A, Okebe J, Ota MO. Risk factors for delay in age-appropriate vaccinations among Gambian children. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):1–9. doi:10.1186/s12913-015-1015-9.

- Mvula H, Heinsbroek E, Chihana M, Crampin AC, Kabuluzi S, Chirwa G, Mwansambo C, Costello A, Cunliffe NA, Heyderman RS, et al. Predictors of uptake and timeliness of newly introduced pneumococcal and rotavirus vaccines, and of measles vaccine in rural Malawi: a population cohort study. PloS One. 2016;11(5):e0154997. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0154997.

- Nankabirwa V, Tylleskär T, Tumwine JK, Sommerfelt H. Maternal education is associated with vaccination status of infants less than 6 months in Eastern Uganda: a cohort study. BMC Pediatr. 2010;10(1):1–9. doi:10.1186/1471-2431-10-92.

- Rammohan A, Awofeso N, Fernandez RC. Paternal education status significantly influences infants’ measles vaccination uptake, independent of maternal education status. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):1–7. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-336.

- Legesse E, Dechasa W. An assessment of child immunization coverage and its determinants in Sinana District, Southeast Ethiopia. BMC Pediatr. 2015;15(1):1–14. doi:10.1186/s12887-015-0345-4.

- Etana B, Deressa W. Factors associated with complete immunization coverage in children aged 12–23 months in Ambo Woreda, Central Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):1–9. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-566.

- Marefiaw TA, Yenesew MA, Mihirete KM. Age-appropriate vaccination coverage and its associated factors for pentavalent 1-3 and measles vaccine doses, in northeast Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. PloS One. 2019;14(8):e0218470. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0218470.

- Aregawi HG, Gebrehiwot TG, Abebe YG, Meles KG, Wuneh AD. Determinants of defaulting from completion of child immunization in Laelay Adiabo District, Tigray Region, Northern Ethiopia: a case-control study. PLoS One. 2017;12(9):e0185533. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0185533.

- Owais A, Hanif B, Siddiqui AR, Agha A, Zaidi AK. Does improving maternal knowledge of vaccines impact infant immunization rates? A community-based randomized-controlled trial in Karachi, Pakistan. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):1–8. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-11-239.

- Chidiebere ODI, Uchenna E, Kenechi O. Maternal sociodemographic factors that influence full child immunisation uptake in Nigeria. South Afr J Child Health. 2014;8(4):138–42. doi:10.7196/sajch.661.

- Doctor HV, Findley SE, Bairagi R, Dahiru T. Northern Nigeria maternal, newborn and child health programme: selected analyses from population-based baseline survey. Open Demograp J. 2011;4:1.

Appendix

English version questionnaire

Part I. Socio demographic characteristics

Part II. Knowledge and maternal health service characteristics

Part III. Vaccination status