ABSTRACT

Background and objectives: Influenza vaccination rates among medical students (MSs) are below the standards recommended in hospitals where influenza vaccination is not mandatory. We carried out a comparative study in two Spanish university hospitals to reassert this fact and evaluated the impact on vaccination rates of a specific program aimed at promoting influenza vaccination among MSs.

Methods: A descriptive cross-sectional study was performed describing influenza vaccination rates and motivations for vaccination during the 2017/18 campaign among MSs in two hospitals affiliated to the same university. We subsequently performed a community-based intervention study during the 2018/19 campaign evaluating the impact of a strategy for promoting influenza vaccination, comparing the hospital where the intervention took place (hospital A) with the one where it did not take place (hospital B).

Results: During de 2017/18 campaign the overall influenza vaccination rate was 44.8%, with no differences between hospitals A and B (difference: 3.9%; 95% CI: −4.36–12.16; p-value = .4). During the 2018/19 campaign, vaccination rate increased to 76.4% in hospital A, with significant differences compared with the previous campaign in the same hospital (29.8%; OR 5.00; 95% CI: 3.14–8.3; p-value = .0001) and with that observed in hospital B in the same campaign (21.1%; 95% CI: 13.38–28.82; p-value <.001).

Conclusions: Influenza vaccination rates among MSs in two Spanish university affiliated hospitals were below the recommended standards. A new reproducible strategy for promoting influenza vaccination with a specific approach toward MSs achieved a significant improvement in vaccination rate.

Introduction

Influenza predominates in winter months and emerges in the form of local outbreaks and seasonal epidemics. It is know that there are some conditions that favor its dissemination such us low temperatures, low humidity and situations that facilitate viral transmission, as for example gathering in closed spaces (schools, hospitals, nursing homes or public transports).Citation1,Citation2 Worldwide, annual epidemics are estimated to result in about 3 to 5 million cases of severe illness and 290,000 to 650,000 respiratory deaths.Citation3 Influenza vaccination is the most effective method to prevent the disease and to reduce its morbidity and mortality.Citation4

Vaccination is especially important in high-risk population and in those who take care of that population. Recommendations from World Health Organization (WHO) for influenza vaccination include pregnant women, children from 6 months to 5 years old, population over 65 years old, patients with chronic pathology, and health-care workers (HCWs).Citation3 The HCWs group is among the groups with less acceptation rate toward vaccination.Citation4,Citation5 Medical students begin to take part of the risk group of HCWs when they start being in contact with patients in medical-care facilities. This fact takes place from the initiation of their hospital-based practices and courses (clinical year students).Citation6 The Spanish National Health System, the WHO and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (CDC-ACIP) recommend influenza vaccinations of medical students.Citation6,Citation7

It has been described a rate of influenza vaccination among HCWs below the threshold established by the WHO for this risk group (60%).Citation4,Citation8–14 Multiple strategies have been accordingly developed to increase influenza vaccination rates among HCWs. These include providing educational material (talks, posters, leaflets, videos), facilitating access to the vaccine (flexible schedules, mobile vaccination teams on designated days, free of cost vaccination), promoting vaccination by health professionals, delivering rewards such as lanyards or badges and sending reminder messages via letter and personal e-mail.Citation15 Nevertheless, influenza vaccination rates below the recommend WHO threshold have been consistently described in the United States, Canada, Japan, South Korea, Australia, Middle East and Europe.Citation16–18

Medical students IVVR are equal or even lower than those obtained by other HCWs.Citation6,Citation19–33 As part of the health care staff, medical students are frequently addressed with similar promotional measures for influenza vaccination.

The aims of the study were, firstly, to obtain IVVR among clinical year students in two Spanish tertiary university hospitals. Secondly, to find out which reasons influence their attitudes toward getting vaccinated or not. Finally, to study and measure the effect of a new reproductible strategy for promoting influenza vaccination in terms of vaccination rates and attitudes.

Material and methods

Study design

The School of Medicine of the Complutense University of Madrid (UCM) admits 320 MSs every academic year through the six-year training. Students are divided into 4 groups of 80 individuals during the first two years. Since the third academic year they become clinical-year MSs and are divided into three hospitals affiliated to the UCM School of Medicine: Hospital Clínico San Carlos (HCSC), Hospital Universitario “12 de Octubre” (HDOC), and Hospital General Universitario “Gregorio Marañón” (HGUGM). HCSC receives every year about 30% of third-year MSs, while HDOC and HGUGM receive 35% each of them. These hospitals have respectively 861, 1196 and 1349 beds.Citation34 HDOC and HGUGM were selected for the present study because they have comparable teaching resources and health-care burden. They are both tertiary care teaching facilities that provide a high-quality subspecialist care, whose number of beds rank among the top 3 and 5 of Madrid´s and Spain´s hospitals respectively and whose number of HCWs is similar (5,408 at HDOC and 5,727 at HGUGM).Citation34–36 More information concerning the comparativeness of both hospitals is available as Annex 1.

In order to maintain the anonymity of the participating hospitals, one of them was designated as hospital A and the other one as hospital B.

The total study population of consisted of 965 MSs: 440 in hospital A (100 from third year, 119 from fourth year, 96 from fifth year, and 125 from sixth year) and 525 in hospital B (132 from third year, 158 from fourth year, 103 from fifth year, and 132 from sixth year). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the UCM School of Medicine and the Instituto de Investigación Hospital “12 de Octubre” (imas12).

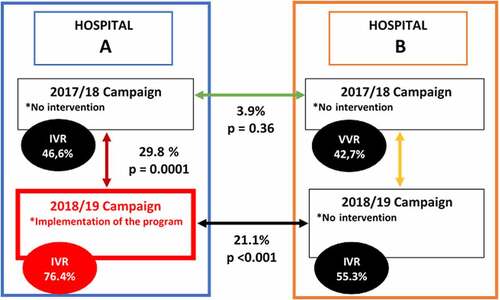

A descriptive cross-sectional study was carried out to determine influenza vaccination rates and reasons for vaccine refusal or acceptance among third- to sixth-year MSs during the 2017/18 campaign. The results obtained in both hospitals were compared (green arrow in ).

Figure 1. Comparisons made in the study for both hospitals across consecutive campaigns. IVR: influenza vaccination rate

In addition, a community-based intervention study was carried out in the 2018/19 campaign, being hospitals A and B the intervention and nonintervention centers, respectively. Influenza vaccination rates and alleged motivations in hospital A following intervention were compared with those reported in the previous campaign (2017/18) (red arrow in ). Influenza vaccination rates and motivations were also compared between both hospitals during the 2018/19 campaign (black arrow in ). Finally, influenza vaccination rates and reasons for vaccine acceptance or refusal in hospital B in the 2018/19 campaign were compared with those observed in the 2017/18 campaign (yellow arrow in ).

Vaccination and intervention program

The vaccine supplied for both hospitals was Chiroflu®, a fractionated inactivated influenza vaccine whose composition met the standards recommended by Regional Health System of the Autonomous Community of Madrid, the European Union (EU) and the WHO for the North Hemisphere in the 2017/2018 and 2018/2019 campaigns. The vaccine for the 2017/2018 season included a strain similar to A/Michigan/45/2015 (H1N1)pdm09 (linage A/Singapore/GP1908/2015), a strain similar to A/Hong Kong/4801/2014 (H3N2) (linage A/Hong Kong/4801/2014) and a strain similar to B/Brisbane/60/2008 (linage B/Brisbane/60/2008, wild type). The vaccine for the 2018/2019 campaign included a strain similar to A/Michigan/45/2015 (H1N1) pdm09, a strain similar to A/Singapore/INFIMH-16-0019/2016 (H3N2) and a strain similar to B/Colorado/06/2017 (linage B/Victoria/2/87).

The official vaccination periods for both campaigns established by the Madrid health administration ran from October 1 of each year until the end of the epidemic period. In both campaigns, the end of the epidemic period was declared in the ninth week of the following yearCitation37,Citation38

Under usual conditions, similar vaccination promotion measures are carried out annually in both hospitals. These measures consist of providing educational material (clinical introduction talk to third-year students during the first days of rotation in their respective hospital and posters in the hospital addressed to HCWs), facilitating access to the vaccine (free vaccination and use of vaccination teams on designated days for on-site vaccination), promoting vaccination by a health-care professional and handing out rewards such as lanyards or badges. These measures are aimed to both clinical-years students and other HCWs.

During the 2018/19 campaign, hospital B maintained the previously described strategy, as in previous campaigns. The intervention was developed in hospital A by a group of four sixth-year students under the supervision of tutors from the Departments of Medicine and Public Health of the UCM School of Medicine. The design was based on the most recommended influenza vaccination promotion measures in previous studiesCitation15,Citation39–41 and those previously carried out in both hospitals. To these mentioned measures, new ones were added ().

Table 1. Bundle of measures to promote influenza vaccination collected in systematic studies, those carried out during the 2017/18 campaign in hospitals A and B and during the 2018/19 campaign in hospital B (nonintervention), and those carried out as an intervention during the 2018/19 campaign in hospital A (intervention)

The intervention began the week of October 29 to November 4, 2018 by giving an informative talk with a PowerPoint presentation to all clinical year students at hospital A. The talk focused on the influenza virus disease, its vaccination and risk groups in which it is indicated, the risk of nosocomial transmission and the problematic low rates of student vaccination at the time. At the end of the seminar, the new promotion program was presented, and MSs were informed that as of November 5, 2018, they could start to get vaccinated at the timing established by hospital A Department of Preventive Medicine and Public Health. Three informative posters of the campaign were also distributed that week at Hospital A teaching area (Annex 2). All MSs were notified on the scheduling of these talks via social media networks (WhatsApp® and Facebook®).

On December 3, 2018, with prior notice on the same social media networks, a team consisting of a doctor and a nurse from the Department of Preventive Medicine and Public Health of hospital A performed vaccination in MSs.

One of the measures implemented consisted of using a sticker () that allowed to identify those students who had been vaccinated in the 2018/2019 campaign. Once the MSs reported having been vaccinated, he/she was given the sticker, which should be placed on the personal identification card required to freely circulate through the hospital. The sticker had a standardized format of 1 × 1.5 cm with the word “GRIPE” (stands for the Spanish translation of influenza) and the two final numbers of the year in which the campaign ended. In this case, a “19” for the 2018/19 campaign.

The intervention ended on January 8, 2019, when the epidemic threshold was exceeded in the Region of Madrid.Citation42

Data collection

A roster including clinical-year MSs of both hospitals was used as sampling frame (965 MSs). A standardized survey (Annex 3) was designed in a printed DIN A4 format to collect all the pertinent data for the study. To increase the response rate, the survey was also designed in a digital format using Google Forms® and made available to students through social media networks (WhatsApp® and Facebook®).

Data collection was anonymous, voluntary and completed with privacy after receiving a brief description about how to fill the survey. The period of surveys collection ranged from March 7, 2019 to April 15, 2019.

The survey was designed using as model similar studies reported in the literature.Citation4,Citation5,Citation7 It consisted of five sections: (a) demography (academic year, hospital and gender); (b) vaccination in the 2017/18 campaign; (c) vaccination in the 2018/19 campaign (being only one response allowed for each item in these sections); and (d) reasons for being/not being vaccinated in each campaign with a repertoire of five and nine possible responses, respectively. In this case, it was possible to select more than one answer and to freely include reasons that were not included. The final section (e) assessed the perception of MSs in hospital A about the impact of the intervention program on their decision to be vaccinated on a scale of 1 (nothing) to 5 (a lot).

Data from both printed and digital formats was collected in a common Microsoft Excel® document file.

Statistical analysis

A descriptive statistical analysis was carried out with absolute and relative frequencies. The percentages were compared using the Chi-square test applying Yates correction when the sample size (n) was lower than 200, or the McNemar test for paired data.

Based on previous studies in the MS population,Citation6,Citation19–33 we expected vaccination rates close to 30% Assuming a confidence level of 95% and a maximum error of 5%, the sample size was calculated to be at least 242 to be representative for the objectives of the study.

The influence that the 2018/19 campaign vaccination program had on the decision to vaccinate among MSs in hospital A was analyzed with the Student’s t-test for paired data, with associations given as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS version 24.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY), MedCalc version 4.16 (MedCalcSofwarebvba), and GraphPad calculator (GraphPad Software).

Results

Out of a total of 965 (57.8%) clinical year MSs, the survey was completed by 558 participants, 369 of whom (66.1%) were women. Classifying the answers collected in the survey by academic year, 143 (25.5%) were obtained in third year, 117 (21.0%) in fourth year, 131 (23.5%) in fifth year and 167 (29.9%) in sixth year. 296 (53.0%) responses were collected at Hospital A and 262 (47.0%) at Hospital B.

In the 2017/18 campaign concerning both hospitals, 250 (44.8%) clinical year MSs reported having been vaccinated (138 [46.6%] in hospital A and 112 [42.7%] in hospital B). No significant differences between both hospitals were observed (absolute difference: 3.9%; 95% CI: −4.36–12.16; p-value = .4).

During the 2018/19 campaign, 226 (76.4%) MSs were vaccinated at hospital A following intervention, as compared to 145 (55.3%) in hospital B (absolute difference: 21.10%; 95% CI: 13.38–28.82; p-value <.001).

The vaccination rate in hospital A during the 2018/19 campaign experienced a significant increase as compared to the 2017/18 campaign in the same hospital (absolute difference: 29.8%; OR: 5.00; 95% CI: 3.14–8; p-value = .0001). A lower increase was observed in Hospital B between the two consecutive campaigns (absolute difference: 12.6%; OR: 2.74; 95% CI: 1.59–4.9; p-value = .0001). shows vaccination rates in these campaigns for both hospitals stratified by gender and academic year. Annex 4 includes an analysis of factors associated to vaccination in the univariate analysis. Only having being exposed to the promoting campaign was found as a factor significantly associated to vaccination (OR 2.61; 95%CI 1.81–3.74; p-value <.001).

Table 2. Results of the sample obtained, stratified by gender and year according to the 2017/18 and 2018/19 vaccination campaigns at both hospitals

According to the information gathered in the survey, the most commonly alleged reasons for vaccination in the 2017/18 campaign were “patient protection” (89.1% and 80.4% in hospitals A and B, respectively) and “self-protection” (80.4% and 83.9%). The less commonly selected motivations were “my colleagues have been vaccinated” (11.6% and 13.4%), “concern about the severity of the disease” (14.5% and 11.6%), and “it has been a commented topic” (23.2% and 23.2%). Alleged motivations for vaccine acceptance or refusal are detailed in and .

Table 3. Reasons collected for being vaccinated according to the 2017/18 and 2018/19 campaigns in hospitals A and B

Table 4. Reasons for vaccine refusal collected according to the 2017/18 and 2018/19 campaigns in hospitals A and B

Regarding the expression of “doubts about the efficacy of the vaccine” for vaccine refusal in hospital A, it was reported by 22 (13.9%) MSs in the 2017/18 campaign and 21 (30%) in the 2018/19 campaign. The reason “doubts about the cost-effectiveness of the vaccine” was selected by 17 (10.8%) and 15 (21.4%) MSs in hospital A in the 2017/18 and 2018/19 campaigns, respectively.

The analysis of reasons for vaccine acceptance more closely related to the intervention program revealed significant differences between both campaigns in hospital A (): “my colleagues have been vaccinated” (absolute difference: 11.0%; p-value = .014), “vaccination facilities” (absolute difference: 10.8%; p-value = .047), “it has been a commented topic” (absolute difference: 28.6%; p-value <.001). On the other hand, there was a decrease in the response rate for “the hospital has not facilitated vaccination” (absolute difference: −12.2%; p-value = .02). In hospital B there were no significant differences in any of the motivations for being or not being vaccinated between the 2017/18 and 2018/19 campaigns ().

Table 5. Comparison of reasons alleged for being or not being vaccinated in hospitals A and B in the 2018/19 campaign compared to the 2017/18 campaign

Finally, an analysis was performed on the perception of clinical MSs at hospital A about the influence of the intervention campaign on their decision to be vaccinated or not. An average of 2.75 out of 5 was obtained, which represents an increase of 1.75 out of 5 (95% CI: 1.59–1.92; p-value = .000) compared to a hypothetical null influence of the campaign. The perception varied according to the year: average of 3.30 in the third year, 2.77 in the fourth year, 2.33 in the fifth year, and 2.53 in the sixth year.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to analyze the impact of a promotional strategy specifically targeted to MSs in terms of influenza vaccination rates and attitudes.

The starting point of the study was based on two hospitals with similar vaccination strategies that resulted in similar baseline vaccination rates. Therefore, we chose to apply the intervention in one of them, with the remaining serving as the control arm. In the intervention hospital, a very notable increase in the vaccination rate was obtained, becoming the highest recorded among MSs, except for those places where vaccination is compulsory (). The probability that a student was vaccinated increased fivefold after intervention. In contrast, the vaccination rate increased only slightly in the nonintervention hospital (55.3% compared to 42.7% in the previous campaign), although it still remained below the recommended threshold. Furthermore, in hospital B there were no significant changes in any of the reasons alleged by MSs in favor or against vaccination.

Table 6. Summary of studies published between 2010 and 2020 regarding influenza vaccination rates among MSs

Influenza vaccination rates among MSs are not as high as they should be for a collective with direct contact with high-risk patient populations. However, a wide range (4.8% to 100%) has been reported (). Where vaccination is not mandatory, vaccination rates generally remain below the 60% WHO threshold except in the UK, where a higher rate has been observed.Citation26 The highest vaccination rates are observed in those Schools of Medicine where vaccination is mandatory for MSs.Citation33 Accordingly, it was considered necessary to devise and apply a promotional strategy to increase influenza vaccination rates in sites where vaccination is not compulsory.

After revising previous literature, it was considered that MSs require a different approach than the rest of HCWs.Citation43,Citation44 Therefore, MSs in hospital A were targeted with a specific bundle of measures making use of current communication technologies that have great influence on students. This approach adds the possibility of debating and receiving feedback, enhancing influenza vaccination to be a commented topic. For example, instead of personal e-mail communications, Facebook® and WhatsApp® were the platforms used. In addition, the measures were promoted by a group of motivated sixth-year MSs in hospital A. The fact that the intervention itself was performed by MSs constituted a cornerstone of the strategy described in this study.

To allow continuous publicity of the vaccination campaign and visibility of students’ vaccination status, the sticker on the identification card was introduced. This method is already used in HCWs from European and US institutions.Citation45 In these hospitals, HCWs who do not carry the sticker on their identification card (i.e. not vaccinated in the present campaign) must circulate through the hospital wearing a surgical mask.Citation45 However, the mask obligation was not contemplated in the implemented program.

To direct the message to the MS collective, educational talks and posters were specifically designed for this subgroup of HCWs, allowing for a closer approach and facilitating awareness. On-site vaccination was available in the teaching area during designated days, since a problem commonly reported by clinical-year students is the “lack of time” for being vaccinated.

The bundle of measures designed is easily reproductible in successive campaigns in different hospitals where vaccination is not mandatory. Although Facebook® and WhatsApp® were used in our study, other social media networks might be more appropriate in other countries.

The promotion strategy led to significant increases in three of the reasons for vaccination (“my colleagues have been vaccinated”, “vaccination facilities”, and “it has been a discussed topic”). The nature of the bundle of measures fits with the reasons just mentioned. Although the individual impact of each measure could not be dissected, the use of the sticker can clearly be related with the reason “my colleagues have been vaccinated”. The sticker was the only method to know at a glance if a colleague had been vaccinated in the present campaign or not. For simple identification, it would be convenient to modify the color of the sticker in each campaign. The visibility of the sticker became a day-to-day discussion topic among students, which had a positive influence boosting vaccination.

The reasons for not being vaccinated changed in hospital A after our intervention was made but the number of students that reported “doubts about the efficacy of the vaccine” and “doubts about the cost-effectiveness of the vaccine” remained constant between both campaigns. This happened even though debates on social media regarding these topics were held between the students. Therefore, the implemented program needs revision to improve its effectiveness in the students who selected those reasons for refusing the vaccine.

The great similarity between the two hospitals selected for this study, one for implementing the promotion measures and the other as a faithful control for comparison, strengthens the reliability of the conclusions. However, this study has some limitations. Firstly, since vaccination was only assessed by the information provided by the surveys, it was assumed that non-responders maintained rates and motivations similar to those observed in the collected surveys. Secondly, data on vaccination rates relied on the veracity of the student’s responses in the survey. However, previous studies among MSs used a similar strategy.

Influenza virus vaccination of risk groups such as HCWs is being even more relevant in the 2020/21 campaign due to the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic. High vaccination rates among HCWs, including clinical-year MSs, might reduce the odds of diagnostic issues among COVID-19 patients in healthcare facilities.

The highest vaccination rates were obtained among third- and fourth-year MSs (87.2% and 83.0% respectively). In addition, these students perceived a greater influence of the campaign on their decision to be vaccinated. This circumstance must be added to the fact that a relation between knowledge gaps and negative attitudes toward vaccination has been described in medical students and other HCWsCitation24 and that having been vaccinated is the most determining factor in deciding to re-vaccinate.Citation29 All this suggests that the establishment of campaigns in the early stages of clinical education is key to ensure higher rates of vaccine acceptance in the future.

Further studies are needed to assure the success of the program in the long term and its reproducibility every year.

In conclusion, the present study confirmed that influenza vaccination rates among MSs in hospitals where vaccination is not mandatory are below the WHO-recommended standards. Moreover, the attitudes toward vaccination observed suggest that this collective requires a specific approach different from other HCWs. An easily reproducible intervention was subsequently implemented, resulting in a significant increase in vaccination rates that could eventually lead to long-term attitudinal changes among MSs.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (9.2 MB)Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website at https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2021.1920269

Additional information

Funding

References

- Treanor JJ. CLINICAL PRACTICE. Influenza vaccination. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(13):1261–68. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1512870.

- Paules C, Subbarao K. Influenza. Lancet. 2017;390(10095):697–708. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30129-0.

- Influenza (Seasonal). [accessed 2020 Jun 16]. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/influenza-(seasonal).

- Vírseda S, Restrepo MA, Arranz E, Magán-Tapia P, Fernández-Ruiz M, De La Cámara AG, Aguado JM, López-Medrano F. Seasonal and Pandemic A (H1N1) 2009 influenza vaccination coverage and attitudes among health-care workers in a Spanish University Hospital. Vaccine. 2010;28(30):4751–57. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.04.101.

- Dini G, Toletone A, Sticchi L, Orsi A, Bragazzi NL, Durando P. Influenza vaccination in healthcare workers: a comprehensive critical appraisal of the literature. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics. 2018;14(3):772–89. doi:10.1080/21645515.2017.1348442.

- Machowicz R, Wyszomirski T, Ciechanska J, Mahboobi N, Wnekowicz E, Obrowski M, Zycinska K, Zielonka TM. Knowledge, attitudes, and influenza vaccination of medical students in Warsaw, Strasbourg, and Teheran. Eur J Med Res. 2010;15 Suppl 2(Suppl2):235–40. doi:10.1186/2047-783x-15-s2-235.

- Recomendaciones de vacunación frente a la gripe. Temporada 2020-2021. [Influenza vaccination recommendations. Season 2020-2021]. Consejo Interterritorial Sistema Nacional de Salud. 2020 May 5. [accessed 2020 May 5]. https://www.mscbs.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/prevPromocion/vacunaciones/docs/Recomendaciones_vacunacion_gripe.pdf .

- Astray-Mochales J, López de Andres A, Hernandez-Barrera V, Rodríguez-Rieiro C, Carrasco Garrido P, Esteban-Vasallo MD, Domínguez-Berjón MF, Jimenez-Trujillo I, Jiménez-García R. Influenza vaccination coverages among high risk subjects and health care workers in Spain. Results of two consecutive National Health Surveys (2011-2014). Vaccine. 2016;34(41):4898–904. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.08.065.

- De Juanes JR, García de Codes A, Arrazola MP, Jaén F, Sanz MI, González A. Influenza vaccination coverage among hospital personnel over three consecutive vaccination campaigns (2001-2002 to 2003-2004). Vaccine. 2007;25(1):201–04. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.10.057.

- Tuells J, García-Román V, Duro-Torrijos JL. Cobertura de vacunación antigripal (2011-2014) en profesionales sanitarios de dos departamentos de salud de la Comunidad Valenciana y servicios hospitalarios más vulnerables a la gripe [Influenza vaccination coverage (2011-2014) in healthcare workers from two health departments of the Valencian Community and hospital services more vulnerable to the flu.]. Rev Esp Salud Publica. 2018;92:e201804019.

- Genovese C, Picerno IAM, Trimarchi G, Cannavò G, Egitto G, Cosenza B, Merlina V, Icardi G, Panatto D, Amicizia D, et al. Vaccination coverage in healthcare workers: a multicenter cross-sectional study in Italy. J Prev Med Hyg. 2019;60(1):E12–E17. doi:10.15167/2421-4248/jpmh2019.60.1.1097.

- Dass von Perbandt E, Hornung R, Thanner M. Influenza vaccination coverage of health care workers: a cross-sectional study based on data from a Swiss gynaecological hospital. GMS Infect Dis. 2018;6:Doc02. doi:10.3205/id000037.

- Hulo S, Nuvoli A, Sobaszek A, Salembier-Trichard A. Knowledge and attitudes towards influenza vaccination of health care workers in emergency services. Vaccine. 2017;35(2):205–07. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.11.086.

- Mytton OT, O’Moore EM, Sparkes T, Baxi R, Abid M. Knowledge, attitudes and beliefs of health care workers towards influenza vaccination. Occup Med (Lond). 2013;63(3):189–95. doi:10.1093/occmed/kqt002.

- Rashid H, Yin JK, Ward K, King C, Seale H, Booy R. Assessing interventions to improve influenza vaccine uptake among health care workers. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(2):284–92. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1087.

- Black CL, Yue X, Ball SW, Fink RV, De Perio MA, Laney AS, Williams WW, Graitcer SB, Fiebelkorn AP, Lu P-J, et al. Influenza vaccination coverage among health care personnel - United States, 2017-18 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(38):1050–54. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6738a2.

- Honda H, Padival S, Shimamura Y, Babcock HM. Changes in influenza vaccination rates among healthcare workers following a pandemic influenza year at a Japanese tertiary care centre. J Hosp Infect. 2012;80(4):316–20. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2011.12.014.

- To KW, Lai A, Lee KC, Koh D, Lee SS. Increasing the coverage of influenza vaccination in healthcare workers: review of challenges and solutions. J Hosp Infect. 2016;94(2):133–42. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2016.07.003.

- Mavros MN, Mitsikostas PK, Kontopidis IG, Moris DN, Dimopoulos G, Falagas ME. H1N1v influenza vaccine in Greek medical students. Eur J Public Health. 2011;21(3):329–32. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckq109.

- Milunic SL, Quilty JF, Super DM, Noritz GH. Patterns of influenza vaccination among medical students. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(1):85–88. doi:10.1086/649219.

- Hernández-García I, Domínguez B, González R. Influenza vaccination rates and determinants among Spanish medical students. Vaccine. 2012;31(1):1–2. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.10.104.

- Wicker S, Rabenau HF, von Gierke L, François G, Hambach R, De Schryver A. Hepatitis B and influenza vaccines: important occupational vaccines differently perceived among medical students. Vaccine. 2013;31(44):5111–17. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.08.070.

- Hernández-García I, Valero LF. Practices, beliefs and attitudes associated with support for mandatory influenza vaccination among Spanish medical students. Vaccine. 2014;32(2):207–08. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.10.073.

- Lehmann BA, Ruiter RA, Wicker S, Chapman G, Kok G. Medical students’ attitude towards influenza vaccination. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15(1):185. doi:10.1186/s12879-015-0929-5.

- Banaszkiewicz A, Talarek E, Śliwka J, Kazubski F, Malecka I, Stryczynska-Kazubska J, Dziubak W, Kuchar E. Awareness of influenza and attitude toward influenza vaccination among medical students. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2016;934:83–88. doi:10.1007/5584_2016_20.

- Edge R, Heath J, Rowlingson B, Keegan TJ, Isba R. Seasonal influenza vaccination amongst medical students: a social network analysis based on a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0140085. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0140085.

- Walker L, Newall A, Heywood AE. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of Australian medical students towards influenza vaccination. Vaccine. 2016;34(50):6193–99. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.10.074.

- Tuohetamu S, Pang M, Nuer X, Mahemuti, Mohemaiti P, Qin Y, Peng Z, Zheng J, Yu H, Feng L, et al. The knowledge, attitudes and practices on influenza among medical college students in Northwest China. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017;13(7):1688–92. doi:10.1080/21645515.2017.1293769.

- Gallone MS, Gallone MF, Cappelli MG, Fortunato F, Martinelli D, Quarto M, Prato R, Tafuri S. Medical students‘ attitude toward influenza vaccination: results of a survey in the University of Bari (Italy). Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017;13(8):1937–41. doi:10.1080/21645515.2017.1320462.

- Fergus E, Speare R, Heal C. Immunisation rates of medical students at a Tropical Queensland University. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2018;3(2):52. doi:10.3390/tropicalmed3020052.

- Rogers CJ, Bahr KO, Benjamin SM. Attitudes and barriers associated with seasonal influenza vaccination uptake among public health students; a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):1131. doi:10.1186/s12889-018-6041-1.

- Vilar-Compte D, de-la-rosa-martinez D, Ponce de León S. Vaccination status and other preventive measures in medical schools. Big needs and opportunities. Arch Med Res. 2018;49(4):255–60. doi:10.1016/j.arcmed.2018.08.009.

- Ryan KA, Filipp SL, Gurka MJ, Zirulnik A, Thompson LA. Understanding influenza vaccine perspectives and hesitancy in university students to promote increased vaccine uptake. Heliyon. 2019;5(10):e02604. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02604.

- Statistics and health information national catalog of hospitals 2019. Updated as of December 31,2018. [accessed 2020 Jun 16]. https://www.mscbs.gob.es/ciudadanos/prestaciones/centrosServiciosSNS/hospitales/docs/CNH_2019.pdf .

- Categorías profesionales agrupadas por centro sanitario. [Professional categories sorted by health-care center] Servicio Madrileño de Salud. Dirección General de Recursos Humanos y Relaciones Laborales. 2021 Jan. [accessed 2021 Jan 1]. https://www.comunidad.madrid/sites/default/files/doc/sanidad/rrhh/rrhh-portal_estadistico_mes_en_curso_07.pdf .

- Madrid Health administration observatory results. Hospitals index. Updated as of May 20, 2020. [accessed 2021 Mar 15]. http://observatorioresultados.sanidadmadrid.org/HospitalesLista.aspx .

- Documentos Técnicos de vacunación frente a la gripe estacional. Temporadas 2017/2018 y 2018/2019. [Technical Documents on vaccination against seasonal influenza virus. Seasons 2017/2018 and 2018/2019]. Consejería de Sanidad de la Comunidad de Madrid. September 2017 and September 2018. [accessed 2021 Jan 1]. http://www.madrid.org/bvirtual/BVCM017999.pdf .

- Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios (AEMPS). Chiroflu® Technical Specifications. [accessed 2021 Feb 28]. https://cima.aemps.es/cima/dochtml/ft/62792/FT_62792.html .

- Robichaud P, Hawken S, Beard L, Morra D, Tomlinson G, Wilson K, Keelan J. Vaccine-critical videos on YouTube and their impact on medical students’ attitudes about seasonal influenza immunization: a pre and post study. Vaccine. 2012;30(25):3763–70. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.03.074.

- Afonso N, Kavanagh M, Swanberg S. Improvement in attitudes toward influenza vaccination in medical students following an integrated curricular intervention. Vaccine. 2014;32(4):502–06. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.11.043.

- Mena G, Llupià A, García-Basteiro AL, Sequera V-G, Aldea M, Bayas JM, Trilla A. Educating on professional habits: attitudes of medical students towards diverse strategies for promoting influenza vaccination and factors associated with the intention to get vaccinated. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13(1):99. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-13-99.

- Instituto de Salud Carlos III. Weekly report of influenza surveillance in Spain. Influenza surveillance system in Spain. Week 02/2019. No. 565. 2019 Jan 17. [accessed 2021 Jan 1]. http://vgripe.isciii.es/documentos/20182019/boletines/grn022019.pdf .

- Hernández-García I, González-Celador R, Giménez-Júlvez MT. Intención de los estudiantes de medicina de vacunarse contra la gripe en sus futuro ejercicio profesional [Attitudes of medical students about influenza vaccination]. Rev Esp Salud Publica. 2014;88(3):407–18. doi:10.4321/S1135-57272014000300010.

- Hollmeyer HG, Hayden F, Poland G, Buchholz U. Influenza vaccination of health care workers in hospitals–a review of studies on attitudes and predictors. Vaccine. 2009;27(30):3935–44. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.03.056.

- Influenza Vaccinations Available for Mount Sinai Health System Staff | Inside MountSinai. [ accessed 2020 Jun 16]. https://health.mountsinai.org/blog/flu-shot-for-mount-sinai-health-system/ .