ABSTRACT

Despite ample evidence of the safety and efficacy of the influenza vaccine and the tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine during pregnancy, two-thirds of pregnant women do not receive these vaccines. Providers have a significant role in increasing prenatal vaccine uptake. It is important to understand how different sources of vaccine prescribing information, such as Food and Drug Administration package inserts, influence provider recommendations. We aimed to examine the role of vaccine package inserts in provider recommendations and perceptions of safety and effectiveness of vaccines during pregnancy. A cross-sectional survey was mailed to a random, weighted sample of American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Fellows living in the United States in March 2019. Providers were asked about their attitudes toward package inserts, and to evaluate sample package insert statements following two different labeling rules. Their evaluations of each rule were then compared. Of the 321 respondents, the majority (90%, 288/321) recommended and/or administered maternal vaccinations. Few respondents (7.8%, 25/321) read package inserts for information regarding vaccination. Respondents were less likely to recommend sample vaccines with Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule-complying inserts (46.1%, 148/321) than vaccines with Pregnancy Category inserts (87.5%, 282/321). Although most providers did not actively utilize vaccine package inserts to inform recommendations, the previous Pregnancy Categories rule was preferred compared to the Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule. Collaborative efforts to update inserts with current clinical practices for pregnancy would be valuable in reducing apprehensiveness around package inserts to generate safer and more cogent recommendations for pregnant women.

Introduction

The United States Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends the inactivated influenza vaccine, and the tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine for all pregnant women.Citation1–4 The safety and efficacy of both vaccines during pregnancy has been demonstrated in many studies.Citation5–13 As of April 2020, 61.2% of pregnant women in the US received an influenza vaccination during pregnancy, 56.6% received a Tdap vaccination, and 40.3% of women with a live birth received both. Higher coverage was reported in women who received a vaccine recommendation from their provider (influenza: 75.2%, Tdap: 72.7%), than in women who did not receive any recommendation (influenza: 20.6%, Tdap: 1.9%). Influenza vaccination coverage in pregnant women improved with an increasing number of provider visits, highlighting the importance of provider engagement in increasing the uptake of vaccines during pregnancy.Citation4

The dearth of pre-licensure vaccine trials in pregnant women prohibits the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) vaccine package inserts from including an indication and usage statement specific to pregnancy.Citation14,Citation15 The regulations on pregnancy, labor and delivery, and nursing mothers in inserts were established by the FDA in 1979 following the thalidomide tragedy. These required each product to be classified under one of five Pregnancy Categories, namely, A, B, C, D or X, based on risk of teratogenicity, or for certain letter codes, based on risk versus benefit.Citation16 This system was hard to explain to the patient while elucidating the balance between risks and benefits of administering the medication (vaccination) during pregnancy.Citation17,Citation18 Several vaccines were categorized as Category B drugs (“animal reproduction studies failed to demonstrate a risk to the fetus, no adequate and well-controlled studies in pregnant women”), despite national and international bodies strongly recommending those vaccines.Citation19 This dissimilarity between FDA-approved labels and advisory committee recommendations, such as those from the US ACIP, has led to the perception that use of these vaccines in pregnant women is “off-label.”Citation14 A study conducted by Top et al. among maternal healthcare providers outside the United States found that the majority of providers from low-, middle-, and high-income countries claimed package insert information affected how they counseled pregnant women. The findings indicated that, much like in the US, providers felt that package insert wording differed from World Health Organization and national immunization technical advisory group recommendations.Citation20

In part as an attempt to address this barrier, on December 3, 2014, the FDA replaced the Pregnancy Category rule of package inserts, with the Content and Format of Labeling for Human Prescription Drug and Biological Products; Requirements for Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling, or the Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule (PLLR). It eliminated the old classification by letter categories and provided a new framework which includes a narrative review of all the risks of using the medication during pregnancy.Citation16,Citation21 While the PLLR does not modify any considerations for vaccinating pregnant women, it does offer more comprehensive information on exposure registries, risk summaries, clinical considerations, and a discussion of supportive facts.Citation16,Citation18 As a result, package inserts following the PLLR are lengthier and expansive, while those that followed the Pregnancy Category rule were shorter and more concise. The PLLR requirements also expanded information under the Pregnancy and Lactation (previously Nursing mothers) subsections and added a new subsection titled Females and Males of Reproductive Potential. However, in 2016, the National Vaccine Advisory Committee (NVAC) recognized that barriers to implementing and understanding the new labeling rules exist. There is insufficient data about level of knowledge and trust in vaccine package inserts among clinicians who provide obstetrical care.Citation17,Citation21All package inserts are publicly available. More information and examples can be found on the FDA website at the online label repository.Citation22

We administered a cross-sectional, nationally representative survey among US obstetricians through the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) to evaluate the extent to which they utilize FDA vaccine package inserts in making prescribing decisions, their opinions on the updated labeling, and their confidence in their ability to interpret the information.Citation20 This data could be used to inform future efforts to educate providers, patients, and national organizations, and overcome this potential perceived barrier to maternal vaccination.

Materials and methods

Sample population

A 24-item self-administered survey was sent to a sample of 800 US practicing obstetrician-gynecologists (ob-gyns) (excluding residents) from a sampling frame of approximately 31,000 practicing ACOG Fellows (board certified ob-gyns). Given the novel nature of this particular study, the predicted magnitudes of providers’ preferences for administering maternal vaccines due to FDA package insert language were unknown. Therefore, we were unable to make a priori sample size calculations. ACOG provided the study team with a random sample of providers, weighted to represent the distribution of population characteristics such as gender, geographic distribution, and subspecialty.

Data collection methods

Since the surveys did not request any identifiable information from the physicians who consented to participate, Emory University Institutional Review Board determined the study to be exempt from further review. Survey packets containing a signed cover letter, printed survey, informed consent, along with a postage-marked return envelope, a pen and gift card as an incentive, were mailed on March 1st, 2019. Providers could utilize the postage-marked envelope to return the hard-copy of the survey or complete the survey online via Survey Monkey (a link and QR code were provided in the cover letter). By completing the survey and returning it to the study staff, respondents provided consent to participate.

Survey design

This survey was divided into three sections. Items were informed by the Top et al. studyCitation20 as well as the literature available on vaccine labels in the United States. The first section included questions about participants’ medical practice and sub-specialty, and their role in vaccine prescribing and administration. The second section utilized Likert-type scales to inquire about their most trusted sources of vaccine information, and how often, if at all, they read package inserts. Lastly, we assessed providers’ trust in, and perceptions of, vaccine package inserts. First, we asked about their level of trust in vaccine package inserts and included an evaluation of the ease of interpreting package insert statements. Second, we provided five mockups of vaccine package insert statements for Fluvirin, Fluarix, Adacel and ProQuad vaccines (vaccine names hidden) with Pregnancy Categories labeling, and updated package inserts with the PLLR.Citation23–27 Participants were asked to rate their recommendation for use and perception of safety of the vaccination from the excerpt, depending on disease prevented, trimester of pregnancy, and whether they would recommend and/or administer vaccines that are also recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). For vaccines also recommended by the CDC, we modeled statements from inserts using the same labeling rule with either neutral or negatively framed sentences. This was conducted to assess the difference of using precautionary language. Statements were extracted from or modeled after package inserts of FDA-approved vaccines complying with either Pregnancy Categories or the PLLR. In the last section, Pregnancy Categories and the PLLR were explained, after which providers were inquired regarding the helpfulness of each rule. The survey ended with an open-ended question, asking respondents for further comments on package inserts and maternal vaccination. Providers were given the option of completing the survey online or mailing a hard copy of their responses in a prepaid envelope.

Data analysis

All quantitative analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and MS Excel. Variables for each quantitative question were set up as categorical for ease of interpretation. For example, questions regarding perception of use and safety of vaccines were separated into “recommendation to use” and “safety of use,” with responses being “yes,” “no” and “refuse to answer.” Since vaccines were deidentified in the survey, with language quoted from inserts with either Pregnancy Categories or PLLR, we were also able to analyze the difference in perception of safety and likelihood of recommendation depending on which labeling rule was followed in each specific insert. Responses were stratified by specialty, years since residency, and whether or not the individual administered vaccines in their practice. We conducted a bivariate analysis to assess which factors were associated with the outcome variable represented by reading the vaccination package. Respondents with missing or a “refuse to answer” response for the outcome or any of the individual factors were removed from this analysis. Differences in proportions were assessed using χ2 and Fisher’s exact tests. Statistical significance was set at a p-value <0.05. Owing to the pilot nature of the study, analyses were largely limited to descriptive exploration. Using hand coding, open-ended responses were analyzed qualitatively through inductive content analysis in order to detect themes for the questions, “What are your thoughts and comments about package inserts’ safety statements under “pregnancy and lactation” for vaccines that are recommended for use in pregnancy?” and “Do you have any other comments to add on vaccine package inserts and maternal immunization?.”Citation28

Results

Out of the 800 surveys to be mailed, 25 could either not be mailed out due to missing labels or were returned as undeliverable. An additional 6 respondents refused to participate, resulting in a survey response rate of 42.7% (328 out of 769). Seven returned surveys were only ~25% complete, and therefore removed from the final analysis for a sample size of 321.

Professional characteristics and practices

Among providers whose responses were included in the analysis, 87.2% (280/321) currently provided care for pregnant women at their practice site. The most common medical sub-specialty of respondents was general obstetrics and gynecology (221/321, 68.8%), and a majority completed their residency > 11 years ago (251/321, 78.2%). Most providers either recommended and/or prescribed maternal vaccination (288/321, 90%). Over fifty percent of providers (56.4%) administered both influenza and Tdap, while 72.9% prescribed both influenza and Tdap ().

Table 1. Professional characteristics and practices among a sample of ACOG fellows, N = 321

Vaccine information accessibility and impression of package inserts

The most frequently used resources for information regarding maternal vaccination were professional organizations such as ACOG (90%) and ACIP/CDC (83.8%). Only 7.8% of providers listed reviewing vaccine package inserts for information regarding maternal vaccination. Seventy percent (226/321) of respondents stated they did not read package inserts, while 17.4% (56/321) read them in case of an updated insert or new product (). Over one-third of respondents maintained they were unfamiliar with the wording of package inserts (110/321, or 34.3%). Twenty-five percent (81/321) stated that package inserts were hard to read.

Table 2. Vaccine information accessibility and package insert impressions among a sample of ACOG fellows, N = 321

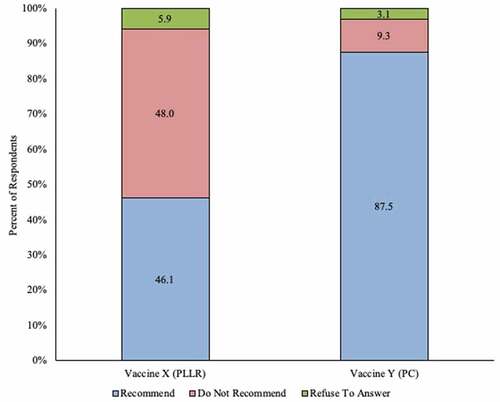

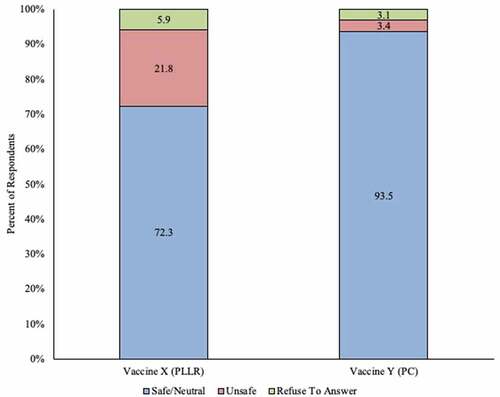

After reading deidentified mock excerpts from both categories of vaccine package inserts (either the PLLR or Pregnancy Category labeling), 46.1% (148/321) of all respondents said they would recommend the vaccine with the PLLR compliant insert, and 87.5% (281/321) stated they would recommend the vaccine with the Pregnancy Categories insert. Seventy-two percent (232/321) of respondents perceived the vaccine with the PLLR insert as being safe for use in pregnancy, or were neutral to it, while 93.5% (300/321) identified the vaccine with the Pregnancy Category insert as being safe in pregnancy, or were neutral to it ( and ).

Figure 1. Initial perception of recommending use in pregnant women among ob-gyns in the US: vaccine with Pregnancy Categories labeling vs. vaccine with Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule (N = 321)

Figure 2. Initial perception of safety of use in pregnant women among ob-gyns in the US: Vaccine with Pregnancy Categories labeling vs. vaccine with Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule (N = 321)

Association of professional characteristics and practices with reading vaccine inserts

We removed 17 providers with non-responsiveness or a “refuse to answer” response for the outcome variable represented by reading package inserts, or the individual categories ‘commonly read resources for information regarding maternal vaccination,’ and ‘recommend and/or administer vaccines in pregnancy.’ This resulted in an analytic sample of 304 ACOG fellows, out of which 27% (82/304) read package inserts. In this sample, the covariates ‘years since residency completion’ and ‘recommending vaccines during pregnancy’ were significantly associated with reading package inserts (). Overall, a higher proportion of respondents who read package inserts had more years pass since residency completion. Approximately 61% (50/82) of those who read package inserts had completed residency >21 years ago, while only 40.6% (90/222) of those who did not read package inserts had completed residency >21 years ago. Across all sub-specialties, a majority of respondents reported not reading package inserts. Recommending and/or administering vaccines in pregnancy was associated with not reading package inserts. Compared to those who read package inserts, those who did not read package inserts had a higher proportion of respondents who recommended and/or administered vaccines in pregnancy (87.8% [72/82] and 95.5% [212/222], respectively) ().

Table 3. Association of professional characteristics and practices with reading vaccine package inserts among a sample of ACOG fellows, N = 304*

Pregnancy Categories and Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule – an overview

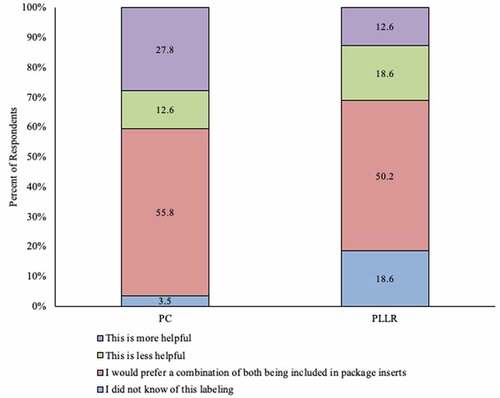

Eighteen percent (59/321) of providers stated they did not know of the PLLR, while 3.4% (11/321) stated they did not know of the Pregnancy Category rule. A majority of providers preferred a combination of both PLLR and the categories included in inserts. Twenty-seven percent (88/321) of respondents stated they considered Pregnancy Categories more helpful than the PLLR in making their decision to recommend or administer vaccines to their pregnant patients ().

Figure 3. Overall opinion on and awareness of utility of Pregnancy Categories and Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule among ob-gyns in the US

For the first open-ended question (comments regarding PLLR safety statements, 70% (223/321) response rate), there were six central themes (). Providers stated that they did not read vaccine package inserts and preferred ACOG/CDC recommendations over inserts. Most deemed the PLLR to be unclear, and “sometimes contradictory” or “convoluted,” with “small print.” Perceiving PLLR language to be designed to avoid liability seemed to be a main theme. Another common theme was that respondents considered package inserts as tools for patients or patient counseling, instead of provider decision-making. Eighteen respondents (8.6% of 210) provided positive comments for PLLR, saying that it was “very much needed,” and that they “appreciated being able to refer to them.” Several respondents stated that due to this survey they would pay more attention to package inserts, and called for more studies to be conducted in pregnant women and for package inserts to be consistent with current practices and guidelines.

Table 4. Themes identified from open-ended question ‘What are your thoughts and comments about package inserts’ safety statements under “pregnancy and lactation” for vaccines that are recommended for use in pregnancy?’.

For the second question (comments regarding vaccine package inserts for maternal vaccination, 41.1% (132/321) response rate), we found seven themes (). A regular theme of package inserts being legal documents emerged in these responses as well, with providers strongly believing that “package inserts are written by lawyers for other lawyers and should not be taken as highly accurate information,” and that the language serves as “protection for manufacturers against litigation.” An additional principal theme was wording being too complex, especially with the PLLR, with a related theme being comfort in using the “old rule” or “relying on the pregnancy categories as busy physicians.” Another recurring theme was providers’ belief that the package inserts were for patients and not for physicians. The last key theme was respondents conveying that they highly preferred ACOG/CDC recommendations over package inserts, and that they “hardly” or “never read” package inserts, owing to confusing language, small print, and lack of clarity.

Discussion

Principal findings

Despite most providers in our sample recommending vaccines for their pregnant patients, vaccine uptake in the US is still modest in this population. Based on our sample, we found that obstetric-care providers are skeptical of vaccine package inserts in general, consider inserts a resource for pregnant women rather than provider decision making and do not generally take such information into account when making decisions regarding vaccines for pregnant women. These findings suggest a lack of confidence in package inserts and, as noted in the qualitative responses, distrust in vaccine manufacturers, among obstetric care providers in the US. These results are in line with provider perceptions of manufacturers observed in a qualitative analysis performed by Top et al., where lack of trust among health care providers was identified as a recurrent theme.Citation29

We also found that although providers generally considered the vaccines safe (or were neutral toward them) regardless of the labeling, almost half of providers would not recommend the vaccine with PLLR labeling, whereas the majority of providers would recommend the example vaccine with Pregnancy Categories labeling. Respondents expressed the need for clearer and succinct wording, and emphasized the need for evidence-based vaccine package inserts that comply with ACOG and ACIP recommendations. Most respondents preferred having a combination of both Pregnancy Category and PLLR labeling, suggesting they favored inserts with subheadings that expand on studies reporting benefits and risks during pregnancy, but also provide a category. Alongside statements from physicians saying they had limited time to read through PLLR inserts, this study suggests that providers are more comfortable with a categorical approach for ease of decision-making.

Clinical implications

When searching for drug information or primary data regarding vaccines, package inserts are an often overlooked, but easy-to-use and freely available resource. Attempts should be made to increase the readability/usability of package inserts in the community of providers who do rely on package inserts, so that a higher number of providers read the Pregnancy and Lactation section. Manca et al. similarly found a need to inform providers regarding label purpose and regulation.Citation30 Additionally, other avenues that influence clinical decision-making should also be encouraged collaboratively along with package inserts, such as educational materials and recommendations developed by professional organizations. This will provide pregnant women and their providers with higher quality data on vaccine safety in the future.

Research implications

Currently, differing recommendations in clinical practice and package inserts may serve as a hurdle to vaccine uptake in pregnancy, and inconclusive statements may be too vague to be a decision-making tool for providers. Our study hopes to inform policy and help vaccine manufacturers, the FDA and CDC, as well as professional organizations to work with risk communication experts and combine efforts to create comprehensive package inserts in unambiguous language that is 1) easy for ob-gyns to interpret and act on, and 2) supports their advice to pregnant women based upon evidence-based recommendations. More studies are needed to examine whether or not reading package inserts can help improve decision-making regarding vaccines in pregnancy, and whether these decisions differ geographically, by practice-type, or by sub-specialty. Research to see how/if reading package inserts influences discussions and decisions regarding pregnant women, will also be valuable. Additionally, it is worth exploring whether pregnant women, in fact, read vaccine inserts. Suggested next steps include conducting targeted surveys identifying which portions of the updated package inserts are most helpful in maternal vaccination decision-making. This could include questions directed at the usefulness and presentation of the narrative sections and subsections, as well as their translatability into clinical practice.

Strengths and limitations

Our study had limitations. The survey was self-administered, leading to a moderate response rate. However, low survey response rates among physicians have been historically common; a 1997 meta-analysis of mailed physician surveys found the average response rate to be 54% (compared with 68% for non-physician mailed surveys).Citation31,Citation32 More recently, the methodology has shifted to web-based surveys, with varied results – response rates have ranged from 34% to 80%.Citation32,Citation33 Despite this, our survey respondents do offer a somewhat representative picture of the ACOG membership; according to reports on ACOG membership, most ob-gyns did not sub-specialize, and were in practice between 11 to 20 years, which aligns with our sample.Citation34,Citation35 At the same time, this was a smaller pilot study and we were unable to conduct a power analysis. Therefore, it is not perfectly representative, especially due to the survey response rate. In order to get a comprehensive opinion from all related medical sub-specialties, we also included ACOG fellows who are not currently taking care of pregnant women, contributing to some of the non-responses for questions regarding professional practices. Less than 8% of the total sample reported actively considering package inserts to inform their recommendations regarding maternal vaccination, which may impact our study results. Further, most providers (70.4% of the total sample) did not read package inserts, which may imply a predisposition to undervalue package insert statements or a lack of awareness of package insert statements, since the sample covers a broad variety of practitioners. Lastly, as previously stated, PLLR is a labeling rule with several components. Thus, it is difficult to fully gauge provider opinions about the labeling rule by only providing a few statements extracted from the package insert. It is possible we might have picked sections that seemed less than useful to participants, or that the statements we selected were insufficient in aiding in the decision-making process.

Conclusions

Our study established that generally, obstetric care providers do not consider vaccine package inserts in decisions concerning maternal vaccination, and instead refer to CDC and ACOG recommendations. Many raised the issue that the package inserts may be patient-facing educational material. When presented with sample package inserts, providers preferred the old Pregnancy Categories over the PLLR, or some combination of both. Qualitative analysis indicated a lack of reliance on package inserts and vaccine manufacturer information. We propose that the FDA, along with vaccine manufacturers, and other trusted professional organizations, work with communication experts to collaboratively 1) update the inserts to reflect most recent guidelines for use in pregnancy, and 2) improve the usefulness of package insert information to generate the best evidence-based recommendations for pregnant women.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

K.A.T has received grants from GlaxoSmithKline and personal fees and non-financial support from Pfizer, both of which were unrelated to the submitted work.

No other authors report any conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by an educational grant from the ACOG Foundation Annual Fund.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Fiore AE, Shay DK, Broder K, Iskander JK, Uyeki TM, Mootrey G, Bresee JS, Cox NJ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2009. MMWR Recomm Rep Morb Mortal Wkly Rep Recomm Rep. 2009;58(RR–8):1–52

- Grohskopf LA, Sokolow LZ, Broder KR, Walter EB, Fry AM, Jernigan DB. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices—United States, 2018–19 influenza season. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2018;67(3):1–20. doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr6703a1.

- Liang JL. Prevention of pertussis, tetanus, and diphtheria with vaccines in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2018:67. doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr6702a1.

- Razzaghi H, Kahn KE, Black CL, Lindley MC, Jatlaoui TC, Fiebelkorn AP, Havers FP, D’Angelo DV, Cheung A, Ruther NA. Influenza and Tdap vaccination coverage among pregnant women — United States, April 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(39):1391–97. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6939a2.

- Omer SB. Maternal Immunization. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(13):1256–67. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1509044.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Updated recommendations for use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap) in pregnant women and persons who have or anticipate having close contact with an infant aged <12 months --- Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(41):1424–26.

- Shakib JH, Korgenski K, Presson AP, Sheng X, Varner MW, Pavia AT, Byington CL. Influenza in infants born to women vaccinated during pregnancy. Pediatrics. 2016;137:6. doi:10.1542/peds.2015-2360.

- Omer SB, Richards JL, Madhi SA, Tapia MD, Steinhoff MC, Aqil AR, Wairagkar N. Three randomized trials of maternal influenza immunization in Mali, Nepal, and South Africa: methods and expectations. Vaccine. 2015;33(32):3801–12. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.05.077.

- Tapia MD, Sow SO, Tamboura B, Tégueté I, Pasetti MF, Kodio M, Onwuchekwa U, Tennant SM, Blackwelder WC, Coulibaly F, et al. Maternal immunisation with trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine for prevention of influenza in infants in Mali: a prospective, active-controlled, observer-blind, randomised phase 4 trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(9):1026–35. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30054-8.

- Steinhoff MC, Omer SB, Roy E, Arifeen SE, Raqib R, Dodd C, Breiman RF, Zaman K. Neonatal outcomes after influenza immunization during pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ Can Med Assoc J J Assoc Medicale Can. 2012;184(6):645–53. doi:10.1503/cmaj.110754.

- Kharbanda EO, Vazquez-Benitez G, Lipkind HS, Klein NP, Cheetham TC, Naleway AL, Lee GM, Hambidge S, Jackson ML, Omer SB, et al. Maternal Tdap vaccination: coverage and acute safety outcomes in the vaccine safety datalink, 2007–2013. Vaccine. 2016;34(7):968–73. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.12.046.

- Sukumaran L, McCarthy NL, Kharbanda EO, Weintraub ES, Vazquez-Benitez G, McNeil MM, Li R, Klein NP, Hambidge SJ, Naleway AL, et al. Safety of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis and influenza vaccinations in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(5):1069–74. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000001066.

- Munoz FM, Bond NH, Maccato M, Pinell P, Hammill HA, Swamy GK, Walter EB, Jackson LA, Englund JA, Edwards MS, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of tetanus diphtheria and acellular pertussis (Tdap) immunization during pregnancy in mothers and infants: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311(17):1760–69. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.3633.

- Research C for DE and. Pregnant women: scientific and ethical considerations for inclusion in clinical trials. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Published May 15, 2020. [accessed 2021 Feb 1]. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/pregnant-women-scientific-and-ethical-considerations-inclusion-clinical-trials.

- Vojtek I, Dieussaert I, Doherty TM, Franck V, Hanssens L, Miller J, Bekkat-Berkani R, Kandeil W, Prado-Cohrs D, Vyse A, et al. Maternal immunization: where are we now and how to move forward? Ann Med. 2018;50(3):193–208. doi:10.1080/07853890.2017.1421320.

- Gruber MF. The US FDA pregnancy lactation and labeling rule - implications for maternal immunization. Vaccine. 2015;33(47):6499–500. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.05.107.

- Overcoming barriers and identifying opportunities for developing maternal immunizations: recommendations from the National Vaccine Advisory Committee (NVAC). Public Health Rep Wash DC 1974. 2017;132(3):271–84. doi:10.1177/0033354917698118.

- Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Guiding principles for development of ACIP recommendations for vaccination during pregnancy and breastfeeding. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(21):580.

- Regan AK. The safety of maternal immunization. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2016;12(12):3132–36. doi:10.1080/21645515.2016.1222341.

- Top KA, Akrell C, Scott H, McNeil SA, Mannerfeldt J, Ortiz JR, Lambach P, MacDonald NE. Effect of package insert language on health-care providers’ perceptions of influenza vaccination safety during pregnancy. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4(10). doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30182-6

- Omer SB, Beigi RH. Pregnancy in the Time of Zika: addressing barriers for developing vaccines and other measures for pregnant women. JAMA. 2016;315(12):1227–28. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.2237.

- FDA Label Search. [accessed 2021 May 10]. https://labels.fda.gov/

- ProQuad. Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp.; 2018.

- Adacel (Tdap). Sanofi Pasteur; 2005.

- Adacel (Tdap). Sanofi Pasteur; 2019.

- FLUARIX. GlaxoSmithKline; 2015:24.

- FLUARIX QUADRIVALENT. GlaxoSmithKline; 2018.

- Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107–15. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x.

- Top KA, Arkell C, Graham J, Scott H, McNeil SA, Mannerfeldt J, MacDonald NE. Do health care providers trust product monograph information regarding use of vaccines in pregnancy? A qualitative study. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2018;44(6):134–38. doi:10.14745/ccdr.v44i06a03

- Manca TA, Graham JE, È D, Kervin M, Castillo E, Crowcroft NS, Fell DB, Hadskis M, Mannerfeldt JM, Greyson D, et al. Developing product label information to support evidence-informed use of vaccines in pregnancy. Vaccine. 2019;37(48):7138–46. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.09.063.

- Asch DA, Jedrziewski MK, Christakis NA. Response rates to mail surveys published in medical journals. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50(10):1129–36. doi:10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00126-1.

- Van Otterloo J, Richards JL, Seib K, Weiss P, Omer SB. Gift card incentives and non-response bias in a survey of vaccine providers: the role of geographic and demographic factors. PloS One. 2011;6(11):e28108. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0028108.

- Cunningham CT, Quan H, Hemmelgarn B, Noseworthy T, Beck CA, Dixon E, Samuel S, Ghali WA, Sykes LL, Jetté N, et al. Exploring physician specialist response rates to web-based surveys. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2015;15(1). doi:10.1186/s12874-015-0016-z

- Rayburn W The obstetrician-gynecologist workforce in the United States : facts, figures, and implications 2011 - NLM Catalog - NCBI. In: American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2017. Accessed February 1, 2021. https://www-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy-hs.researchport.umd.edu/nlmcatalog/101542193

- Kelly R Profile of Ob-gyn practice american college of obstetricians and gynecologists. Published online; 2003.